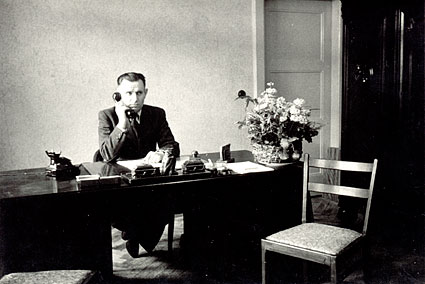

My father Isaac Stel'makh in his office in the military administration in Berlin. This photo was taken to send it to the family in Kiev in 1946.

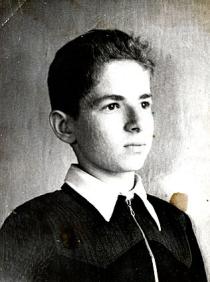

My father was the product of his epoch. He went to cheder like all Jewish boys and then finished a Jewish school. And then… I would say he was drawn in with the 'wheel of history'. He left his home at the age of 14. He headed to Kamenets-Podolskiy, 100 km west of his home where he joined Komsomol. He became a Komsomol activist. By the age of 20 he already joined the Communist Party. In the latter 1930s our family moved to Kiev. I don't know exactly what work my father did for a living, but he earned well and was prosperous. He bought a motor cycle, a film projector and a piano for the children to study music when they grew up.

In 1941 my father finished his artillery school in Gorliy town and went to the front. Fate guarded my father, though he was wounded several times. After hospitals he went back to the front. My father reached Berlin. After the victory he got in a car accident and stayed in hospital Sharita in Berlin for almost a year. Then my father resigned from the army, but was assigned to the Soviet Military Administration of the town. In 1947 he came to take us to Berlin. We were taken to a wonderful apartment of 8 rooms. I don’t know what position my father had, but we had a nice life.

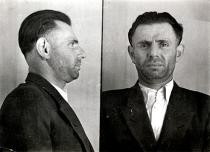

On 20 January 1949 state security officers came to my father's office and asked him to follow them. He didn't understand at once what it was about. Only when they asked him to take off his tie and untie and remove his shoe laces, he understood that he was arrested. He was accused by article 58, item 10: anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. He was taken to Spandau, a prison in Berlin. For ten months my father underwent tortures during interrogations. They tried to force him to write evidence against himself that he called to overthrow the existing regime and Stalin. My father didn't succumb. They tried all methods of NKVD: torture with hunger, when an investigation officer was eating cutlets with fried potatoes before my father who hadn't eaten for several days, night interrogation, when they didn't allow a person to fall asleep and woke him up the moment he fell asleep. Besides, my father, an inveterate smoker, suffered without cigarettes, and an interrogation officer smoked good cigarettes in front of him. In November 1949 the investigation officer said that if my father didn't sign his confession, he was to be 'acted' on the following day (in the NKVD language it meant that a person was killed and an 'act for death from a heart attack' was issued). My father was thinking all night through. He decided to sign the confession or he would die. He thought of saying that he was forced to do this in court. My father still believed that this was misinterpretation of the party policy and that the just Soviet court would know what was right. The interrogation officer said this was quite another matter. He gave my father a cigarette and somebody brought him food. Next day the investigation officer read to him that by decision of the special meeting he was sentenced to 10 years in jail.

In September 1954 my father was released. He was not rehabilitated, though, but, as his certificate of release indicated, his sentence was reduced from 10 to six years, and he was released before term for good performance and behavior. On 14 August 1956 the Military Collegium of the supreme Court of the USSR reviewed the case of Isaac Stel'makh and closed it for absence of corpus delicti. My father was rehabilitated.