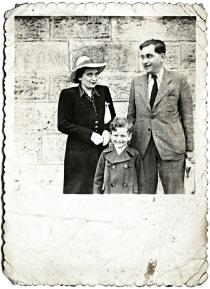

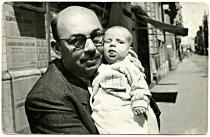

This is my daughter Julia (left), my sister Anna (right) an me during a beautiful excursion in Szentendre, near Budapest, in 1972. We loved going for nice walks and excursion the three of us.

Julia was born in 1949. When my father was on his deathbed I promised him that my mother would live with me. In fact it was much easier for me like that, because Juli was six months old when I had to give up my fashion shop and had to go to work. They took my baby away from me. For twenty-one years, my work was such that I was at home in the flat. So if my child cried, I could go to her in the other room. My mother reared her from her age of six months. I had a domestic helper. When I had my fashion shop it was cheaper to have one, than to do the cooking and the cleaning in my own time. I got my job during the summer and Emi, the domestic helper, said she would take Juli in. They went away for two weeks that was the holiday due to Emi. I gave her an addressed card for her to write each day. I could not have provided such things for her in Pest in 1950; she got the first milk from the morning milking and every day they killed a chicken to get the fresh liver into her soup.

Juli was head of the class in the gymnasium. She was accepted at her first application to the Theater Academy. The next day I went to work very happy and met our legal adviser, who told me, 'You shouldn't be so happy. It is a bumpy career, someone either is very successful in it, or not.' I've thought so many times. I am very sorry for Juli's actual life. She got her diploma in 1971, and she was in the provinces. She got a contract in Debrecen first. From there she went to other provincial towns. I retired when Juli got her diploma.

We did not speak about religion at home after the war. My mother was observant and Vili her husband was too. But I said that we could not educate the child in two different ways. If she was told something at school, we could not tell her any different. She didn't notice that the dinner was different and at a different time. And in 1956, under the revolution, the order came that beginning in September 1957, religious education classes would be started. The ones who wanted their children to attend had to sign for it. I did not want to, but Vili signed that she should attend the Jewish religious classes. Juli accepted it without knowing what it was.

Her next meeting with Jewish life was when a classmate of hers came to our place to play. At that time biscuits were sent in colourful boxes by Jewish organisations and the other girl liked them very much. My mother told her that she could take them home if she wanted to. The girl replied that she could not take them home, because then her parents would know that she had been to a Jewish girl's house. My mother told her: 'Forget about the boxes then. Look, you can lie however you want at home, but don?t come here anymore.' From then on, Juli knew that she was a Jew. We never spoke of it. Then she noticed that there were matzoh dumplings at Pesach. There was the dinner beforeYom Kippur, and Vili fasted and prayed. I did not fast. I couldn't. My work mates never asked me 'Are you coming to have lunch?,' but they always asked me on Yom Kippur. I worked on every Yom Kippur. Juli knew several things by then, but not too much, and she didn't ask. Emotionally, she became a Jew at that time.