This is my daughter Halinka. I cannot say how old she is in that picture. It was taken for some ID.

My parents-in-law had left a house in Kalwaria, and in 1949 I sold that house. My husband had brothers and sisters, but somehow they all ceded at least part of it to me, so I had a little money and I was able to go on a trip to Israel. For a month, that was how much leave I had. That trip cost a lot. Actually, I'd wanted my daughter Halinka to go to Israel instead of me - after the war she was grown up. But she didn't want to, and we wouldn't both have got permission to leave the country. They didn't let people go to Israel, because they were afraid to let their precious Jews go. I had a lots of problems, I was refused permission to go several times, but in the end I succeeded and I went. That was in maybe 1952 or 1953. I thought that in time I'd persuade Halinka; I was brought up in a very Jewish home, but she wasn't.

As far as I remember, I flew from Warsaw. I got on a plane that landed in Haifa. Janek, my cousin, came to the airport for me. He and his sister Ewa left Poland before the war. They tried to persuade me to stay, but I said: 'I can't, because I've got my daughter in Cracow.' I didn't want to part with my daughter, and she desperately didn't want to emigrate - she was a Pole. Did I bring my daughter up in the Jewish faith? I didn't bring her up to be a Jew at all. She just has 'Jew' written in her papers. I'm not religious either, but I am a Jew by nationality. She doesn't feel Jewish at all.

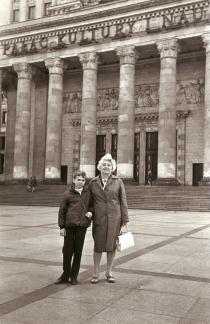

I had plans to move to Warsaw, I had the chance of a good job, but Halinka didn't want to go; I had all sorts of problems. I took her to Warsaw, and she came back. So then I said: either you go to work, or you go to school. She was 18. She went out to work in her final year at school, took her school-leaving exams while she was working. Well, what did I have to live on? She worked 3-4 years in Huta [the Lenin Steelworks, built 1954, the largest industrial plant in the Cracow region, now the T. Sendzimir Steelworks]. Then she worked in Cracow as a Russian translator - after all, she'd been at school in Russia for several years. Then she did a part-time university degree, in Russian.

After we had to leave the children's home, Halinka lived with me at first. I found a tiny room at 48 Karmelicka Street. Then, while she was doing her degree she got married and I lived with her and her son [Ryszard Bronislaw, b. 1959], and her husband, a medical student, lived with his parents. Oh, it was all kinds of fun. The owner of the apartment was a very pleasant Mrs. Jenerowa, an Italian woman who'd married a Pole who worked in Cracow in the days when it was Galicia [i.e. before World War I]. So to the time we knew her, she didn't speak Polish perfectly. A very genteel, immensely pleasant, good person. It was a 3-room apartment. She lived in one room with her maid, in the second room was a Mrs. Tatarowa, who'd been married to a Jew, but her husband had perished in the occupation, and in the third room us, together with my grandson.

When a room came free in my friend's apartment on Slowackiego Avenue, I moved in with her, and at least they could live together. Shortly afterwards Halinka divorced him. He moved out. His parents wouldn't let him back in their apartment. In the meantime, Ryszard was with me more than he was at home with Halinka, because Halinka was working. I worked too, but we managed somehow. He was sick a lot, had high fevers, so he didn't go to school, but stayed with me. I was constantly taking him on vacation or on trips. When Halinka was in Russia, he lived with me. She was there for 7 or 9 years, working as a translator. In Smolensk somewhere, then in the Crimea - various, in different places.