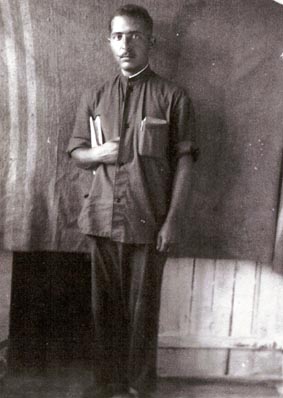

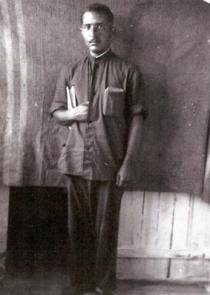

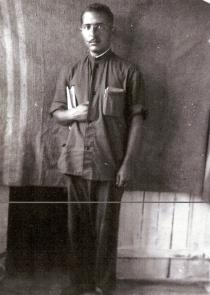

This is me photographed in prison in Lvov in 1953. I had this picture taken to send it to my mother.

I graduated from the Pedagogical Institute in 1951 and was supposed to receive a job assignment in the girl's school in the center of Lvov, where all best students were sent to work. But this vacancy was given to the daughter of the first secretary of the town party committee. I got an assignment as inspector of the district education committee in a town in Lvov region instead. I worked there for a month and a half until I was appointed deputy director in the village of Dobrotvor. It was a big lower secondary school with some 430 pupils. It was housed in a long barrack. This barrack was a shabby facility. I was young and full of energy and kept writing letters to the district management saying that it was necessary to build a new school in Dobrotvor. The director of the school didn't like it. He called me once and said, 'Kamyshan, you'll pay for writing these letters. If the Germans didn't do with you, we shall'. I replied that I wasn't going to stop writing letters until the children got a new school.

Well, the next event in my life was that I was put into prison. Here is what happened. The local children weren't willing to become pioneers. They were against the Soviet power. Many families were arriving from Eastern Ukraine. Their children came to school and they were pioneers. Once a local boy hit a boy from Eastern Ukraine demanding that he took off his pioneer's necktie. That pupil was a big boy and he began to smother that boy with his red necktie. I came to his rescue and hit that boy on his face several times. The other children were watching the scene. An investigation officer came and opened a case against me. The trial was scheduled for 17th June 1953 during final exams. My pupils came to school early in the morning to take their exams in history, and later we all went to the court sitting in the district town.

I was sentenced to three years imprisonment for exceeding my office commission and was deprived of the right to be a teacher in the future. I was put into jail in Lvov. What saved me was my good memory and the possibility to read. There was a thief in this jail that held a higher hierarchal position among inmates. He liked to listen to stories I told him. I told him a lot from the historical novels and other books that I had read. He took me under his guardianship: The others didn't touch me, nobody opened the parcels that my mother brought me, and I had the best spot in the cell.

There were usually several inmates in one prison cell. The attitude towards newcomers was cruel. They were beaten and punished for everything they did and weren't allowed any freedom. They got a place to sleep near the toilet. Once the thief asked me why I was sentenced and advised me to submit a request to transfer me to a camp. I submitted quite a few such requests. There was no anti-Semitism in jail. I stayed in this prison in Lvov for over a year. My mother brought me parcels and supported me in every possible way. Later I was sent to a camp to cut wood in the Belyie Sady, near Moscow. I worked in the library and club of the camp.

In 1955, at the solicitation of Ukraine's Minister of Education, I was released from prison and cleared of all the accusations, and the judge that had heard my case was fired. But it was impossible to find a job in Lvov. I got a job assignment to work as a teacher in a village.