Eva Meislova

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Pavla Neuner

Date of interview: March 2003

Eva Meislova lives in a small apartment in a Jewish pension full of original paintings collected by her father. Her apartment is gracious and full of flowers. In addition to the paintings she has big wooden trunk from her mother. Although she spent most of her life under the communist regime and suffered under the Nazi persecution, she is a very kind and open-minded person and interested in public events. She was keen on all different kinds of sports in her youth and is still in good shape, both physically and mentally. She goes for a walk daily.

Family background

My paternal grandfather, Jakub Bohm, was born in Batelov, Moravia, in 1861. His father had a drapery factory and died when my grandfather was a kid. When my grandfather grew up he managed the drapery factory with his brother, but they went bankrupt. Later he was a coachman and had a buggy pulled by a horse. He liked to play cards and enjoy life. My paternal grandmother, Veronika Bohmova, [nee Redererova], was born in Celkovice, near Tabor, sometime in the 1860s, but I don't remember when exactly,. Her father was a shammash in Tabor. She had a brother, Ignac Rederer, who gave lectures at the university in Prague. I didn't know him very well; they weren't in touch that often.

When my grandfather got married to my grandmother he moved from Moravia to Celkovice where she lived. Celkovice was a suburb of Tabor at that time. He opened a drapery shop in Tabor. He employed one shop assistant and a few tailors and a foreman in the workshop, which was next to the shop. They sewed clothes for man, mainly uniforms for the garrison in Tabor. My grandparents lived about 15 minutes walk from our place. It was a nice house with a garden, situated next to the river. They didn't have electricity so they used oil lamps, and the toilet was in the yard. My grandfather used to sleep in our house, except for the weekends, because it turned out to be too far for him to go back to Celkovice every day. He stayed in the shop until evening and then he arrived and read the Prager Tagblatt. [This was a German-language daily newspaper.] My grandmother had her own friends but they weren't Jewish because there were no Jewish people in Celkovice. They met and talked but in general they didn't have very much spare time.

My grandmother was a housewife all her life. She had a maid at home for help. She was breeding hens as a hobby. My grandfather wasn't religious at all, he only went to the synagogue on Yom Kippur. He came from an ordinary Czech-speaking family, but he was a big fan of Austria-Hungary. My grandmother was religious but not extremely so; she kept a kosher kitchen, observed Sabbath and went to the synagogue on Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. Celkovice was a small village, and my grandparents were living in the same way as the other Czechs. They were concerned about their family, house, garden and business.

Shortly before World War II my grandparents moved to an apartment in Tabor because my grandfather was already too old to work. At the beginning of the war they moved to our big apartment following the order that Jews could only live in certain parts of town. My grandparents went to the concentration camp Terezin 1 with us and died there. My grandfather died in 1942 when he was about 80 years old. My grandmother died a month later because she was old but, I think, also because she was used to him and suffered from his loss.

My father, Alois Bohm, was born in Celkovice in 1885, but he lived in Tabor all his life. Tabor was a calm countrified town without industry, there was only a malt-house and a tobacco factory. Before World War II about 15,000 people lived there. It was surrounded by a beautiful hilly landscape with lots of woods. There was a lake called Jordan, in which we used to swim in the summer. The Jewish cemetery was on the outskirts of town. Due to the mayor of the town there was quite a big Czechoslovak garrison [after WWI]. Barracks were built for the soldiers, and later they served for the Gestapo. There were about 800 Jews in Tabor, but none of them was really religious. The Jews in Tabor were mostly middle-class, not very rich but not very poor either. There was one Jewish factory-owner but most of the other Jews were just small businessmen.

I don't remember if my father studied anywhere. He was a businessman. He got his business license and became my grandfather's partner in the drapery shop. He wasn't religious. He didn't go to the synagogue except for Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. My mother said that he actually withdrew from the Jewish community because they asked him for too much community tax. He smoked a lot and drank a lot of coffee, but he didn't drink alcohol. My dad was this kind of sociable Jew, his 'sport activity' was limited to visiting the coffee shop and meeting people there. I used to go for a walk on a very beautiful, long pathway through the wood on Sundays with my mum. My dad always said to my mum that he would go to the coffee shop to meet people instead and asked her to join him later. So we were walking until four o'clock in the afternoon, and afterwards she met him in the coffee shop.

My dad had one sister. Her name was Julie, and she was a bit younger, two or three years, than him. She married a Christian man named Belohlavek. He was a very religious Christian and went to church very often. He was the director of the Sporitelna Bank in Prague. They lived in a beautiful three- bedroom basement apartment in a noble district of Prague. Their apartment was next to a large garden. We always walked through the gardens when we wanted to get to the center of the city. Uncle Belohlavek and Julie didn't have any children together. My uncle had a son from a previous marriage.

When my uncle was already retired he became quite a strange person. He underwent some rejuvenation cure when he was already over 60 years old. He put on high heels, painted his nails red and wore a corset. He also underwent prostate surgery which wasn't successful and, along with the treatment, caused his death at the beginning of World War II. Aunt Julie turned crazy because of it, walked the streets without the Jewish star attached, and someone reported her. She was in Terezin but I don't know where exactly she was killed. My mum thought that Belohlavek junior reported Aunt Julie because of the property. Belohlavek junior got married to some girl who wasn't good for him, according to his father. They didn't communicate with him and disinherited him. At the beginning of the war their son started to visit them from time to time. After the war he lived in Tabor and worked in a bank, but I wasn't in contact with him, and he didn't show any interest in communicating with me either.

My maternal grandfather, Josef Kraus, came from a Czech family. He was born in Cechtice in central Bohemia, and he also died there before World War II. He had a heart failure, was paralyzed as a result and spent the last ten years of his life bound to bed. I didn't know him very well. He had a small shop selling various products, and I know he tried to work in agriculture because he also owned some fields. My mum said that no seeds ever grew and that each pig they bought died shortly afterwards. So that part of business didn't get them anywhere.

My grandparents had a small village house, which included the shop, situated in the village center. My grandfather wasn't religious at all, and neither was his wife, my grandmother, Pavlina Krausova [nee Fischerova]. She came from Mlada Boleslav and moved to Cechtice after she married my grandfather. She was quite a smart woman with a good knowledge of cultural and historical events. My grandfather and her weren't a good match at all; I don't know where and how she wound up with him. After his death she moved to her sons in Prague. She didn't survive the Holocaust.

My grandparents had six children. The oldest, Rudolf, died as a soldier in World War I. Emil was a dentist. He lived in Karlovy Vary with his wife Eva and their two children. He died in 1933 of blood cancer. Bedrich was a clerk with the Union Bank. His wife's name was Dorotea, and they had two children. Bedrich was murdered in Auschwitz. Then there was my mother, Stepanka Bohmova [nee Krausova]. Next was Frantisek, who lived in Prague and ran a business manufacturing hand-embroidered clothes and evening clothes in the center of the city. The name of the company was Makra and it was successful. They made very beautiful things, and they even sold their products to the Castle [the seat of the government]. The youngest of my grandparents' children was Anna. She lived in Kralupy, near Prague, and was my favorite aunt. Anna ran a shop selling paints and varnishes. None of the siblings was religious.

My mum was born in Cechtice in 1895. Although she came from a Czech family she received German elementary school education. She was a young girl from a good family so she stayed in a girl's boarding school in Teplice, where she lived and studied and was preparing for family duties. It was a German secondary school.

My mother met my father on the train, and it was love at first sight. They had a Jewish wedding, and she moved to Tabor with him afterwards. She was a housewife, and in the afternoons she went to help my dad in the shop. She wasn't very religious. She only went to the synagogue on major holidays and much more to show off a new dress than for religious reasons. There was a big beautiful two-storied synagogue in Tabor, where women had places on the balcony. Praying women were sitting on the left side, and the right side was full of women who just came there to meet and talk. The praying women were rebuking them for disturbing them.

On Yom Kippur we went to the synagogue. When we returned my paternal grandmother arrived. My mum prepared dinner: It used to be barkhes and some chicken. My mother and grandmother fasted but we, the children and my father, didn't. My mum always said to my father, 'You only observe the holidays because of the food.' We didn't go to school on Yom Kippur but the drapery shop was open.

Growing up

Our family belonged to the middle class; we were neither rich nor poor. My dad was officially the head of the family, but it was my mum who managed the house and family matters. She got a monthly salary from my dad and organized everything at home and everything concerning us, children. She was very joyful, loved to talk and was very popular in Tabor. People in Tabor were still remembering her a long time after her death. She liked to dress nicely and even had a personal tailor in Prague. She didn't have too much hair so she was wearing hairpieces. She was always very elegant but above all a very happy person. My dad, on the other hand, was a serious person. They loved each other a lot.

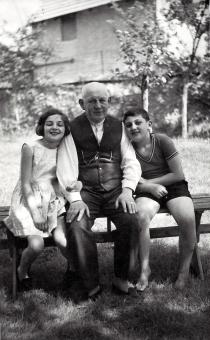

I had an older brother, Rudolf Bohm, who was born in Tabor in 1921. He finished a Czech gymnasium but wasn't allowed to continue the studies then because of his Jewish origin [because of the exclusion of Jews from schools in the Protectorate] 2. He was a boy scout when he was small. We had an average relationship, just like an older brother and younger sister tend to have. I remember I was crying when he refused to dance with me at dancing courses. My mum said to me, 'Don't cry and be glad that you have enough other suitors.' Rudolf was a very handsome and smart boy. He was the educational type and wanted to become a psychiatrist. Rudolf was the member of a hakhsharah 3. He spent two summers with them training in agriculture work. They lived there together and shared the money they earned. It was kind of a kibbutz life. The next year, that was either in 1940 or in 1941, my brother was already sent to forced labor. He worked on the river regulation in Sezimovo Usti. He was also working as a manual laborer when Bata 4 started to build houses in our region.

We lived on the first floor in an old house. We had a large apartment, three big rooms and a small one for the maid. We had a living room and a dining room with black furniture. My parents slept in the bedroom, and my brother and I in the living room. We had electricity at home and cold running water. We warmed the water in a high-tile stove, which we used for heating. There was a coal stove for cooking in the kitchen. My dad was always cold, and I recall him reading the Prager Tagblatt leaning against the stove and warming up. During the winter we only heated one room. The apartment was rented because my mum never wanted her own apartment. She always said that you only have to pay the rent and have no other troubles. I never wanted to own a house either. Later someone bought our house, and he planned some reconstruction that my mum wasn't fond off. So she found another modern apartment but in the meantime the Germans arrived, and we had to stay. The owner then made the reconstruction in our apartment and transformed our hall into a small room, into which the Germans moved a Jewish family.

We had a maid who lived with us and helped my mother with the housekeeping, but she wasn't taking care of us. Maids were usually young girls from villages who wanted to earn some money. So they went to work, and then they often got married and left. We liked them but my parents kept some distance. We didn't have Jewish maids or any other Jewish girls for help. Whenever Jewish girls worked for a family, they were only looking after the children. We had a few Jewish friends who were visiting us from time to time but not because of their origin. We knew a few more religious families in Tabor but most of the Jews didn't even observe Sabbath. Jews in Tabor for the most part only observed the high holidays. In those small towns Jews usually lived like the other Czech people. We celebrated Christmas and New Year's Eve like most of the people in town.

A girl from a good family was supposed to play the piano, so my mum bought a piano for me. It stood in the corner of the living room. I wasn't talented at all but I had to play. I also took classes with piano virtuoso Mrs. Marketa Koprova but I was never good. Each day after lunch I played the piano, my brother was fiddling, and when the windows were open we heard my future husband, Jiri Meisl, play the piano too, so in a way we were making music together.

I finished the Czech school in Tabor, where we learned German from the 3rd grade. I think that the school-leaving exam was also in German. We also had religion classes. Then I attended gymnasium but I had to leave after the 5th grade, when we started to learn French, due to the fact that I was Jewish. I was the only Jew in our class. There were a few more Jews at school but not in my class. We had three elementary schools and two secondary schools in Tabor but no special Jewish school. Pupils attended the schools depending on their place of residence. I still visit our gymnasium class meetings today although I hadn't passed the school-leaving exam with my former classmates. They say it doesn't matter because they consider me one of them. Our class was a girls' class and all of them always behaved well towards me. I cannot complain about anything concerning anti-Semitism. My schoolmates didn't regard me as a Jew, and I never experienced any anti-Semitic acts from their side.

When I had to leave the gymnasium, my mum put me into a home economics school, which I fortunately only attended for one year. We were learning how to handle our future family duties, which I really wasn't fond off. My mum apprenticed me to a seamstress and was paying her 30 crowns a month. I liked school, and I always had good marks. I wanted to become a pharmacist. I had private lessons in English, German and French before the war. I was pretty good at sports. I used to go to Rytmika, where we were dancing to music. In winter I went skating and skiing. I also went to Sokol 5 for exercising. I was also a member of the scout group. I went to a summer camp with them two or three times, but I stopped before they could exclude me for being Jewish. I've never felt too much anti-Semitism. I just remember one incident: I was waiting at the doctor's and when it was my turn to go inside, I heard a fascist, a member of the Vlajka 6, screaming that as a Jew I should be waiting and be the last in the queue. After World War II this man was caught and put on trial. I know that because my husband went to see the trial. Later this man had serious health problems, and in the end he was visiting Jewish doctor!

We had a car, a Cabriolet Tatra. [Editor's note: Before 1939 many car factories existed in the Czech lands, the best-known were Laurin & Klement, Tatra, Jawa, Praga and Aero. Cabriolet Tatra was a car for the higher middle class.] We went on trips very often. My most favorite places were Orlik and Zvikov, where we could swim in the summer. [Orlik and Zvikov are resorts situated on the river Vltava, about 50 kilometers from Tabor.] Although my dad was born near the river he couldn't swim, and he was always running along the shore warning us to be careful not to drown. I didn't like car rides because I was always carsick. Even after I got married I couldn't stand traveling by car or train. Once a year my dad and his friend Svehla, who was the director of a school in Borotin, went on a longer trip, for instance to Slovakia, about 400 kilometers from Tabor. They spent a week hiking in the mountains. They had canes on which they put stickers of the places they had visited. Usually we didn't go that far away; not even during the winter because we had enough snow in Tabor to ski there.

We also had a dog, a foxhound, whose name was Maxel, and, after his death a canary. Maxel learned to go to our neighbor butcher, and she always gave him something to eat.

We didn't celebrate Jewish holidays. Uncle Belohlavek was a very religious Catholic, and his family always came for Christmas, which we celebrated. He was rich so he brought candies to hang onto the tree and presents. We ate fish and potato salad. We didn't even know about Chanukkah. We didn't stick to kosher food, we ate pork and everything else. My mum bred geese in the cellar for meat and fat. As to Jewish meals, we only ate cholent and challah on Yom Kippur.

We ate together, the dinner was at 7 pm, and my parents strictly kept this rule. My brother once asked if he could be late. He had a girlfriend and wanted to accompany her home. There was a promenade in the center of town, and my mum told him: 'Take her to the corner at Kubes, and apologize to her that you have to be home for dinner.' We also had lunch together every day. I only had school classes in the mornings, and even when I was in gymnasium and had afternoon lessons, everyone went home for lunch. My dad also closed the shop and went home for lunch and to have a short nap.

We had a rabbi, a cantor, a shochet and a shammash in Tabor. They lived in the former Jewish school. The rabbi taught religion and the cantor assisted in the synagogue. There was a Jewish school before World War I but not in my time. We didn't have a mikveh or yeshivah. Most of the Jews in Tabor were assimilated businessmen. Jews didn't live in any special part of the town. It was only later, during the war, when Jews weren't allowed to live in the center of town.

Neither my dad nor my granddad cared much about politics, and they weren't politically involved at all. My father voted for the Zivnostenska Party 7, but he used to say that the best 'party' is the relationship between a man and a woman. My mum joined a kind of friends club that we used to call 'club of old virgins'. About ten Jewish and Christian women used to gather. They either met in the coffee shop or at their homes and prepared some food and chatted. They also got together on New Year's Eve for a little afternoon party. After World War II my mum was the only Jewish woman from this club who had survived and it wasn't the same as before, so they stopped their meetings.

It didn't matter to us whether our friends were Jewish or not. I had two very good Christian friends, one isn't alive any more, the other one I still visit in Tabor once in three months for four days. Her name is Jaroslava Teclova, and she is my oldest friend. We have known each other from our childhood. Jaroslava was a kindergarten teacher and her husband was a doctor. We went for long walks in the woods very often. She says that since I have moved to Prague, she is getting fat because she doesn't have anyone to go for a walk with. She lives with her son now.

My husband was born in Cerveny Ujezd, near Benesov, in 1921. In 1930 his parents bought a house with a shop in Tabor and moved there. Jiri celebrated his bar mitzvah with his relatives, and I remember that he got his first watch. That was in July 1934. He lived with his parents and his brother Richard. We started dating when I was 15. Jiri was also very good friends with my brother Rudolf. They were in the hakhsharah together, as well as in forced labor and in the concentration camps. Our parents were also friends. He also came from a Czech family. He finished his studies in a two-year trade academy before World War II and worked for a while in the office of the Velim confectionary factory. Then he stayed at home because he wasn't allowed to work anymore.

I had a lot of Christian friends and didn't feel very Jewish, so I didn't notice the growing anti-Semitism. I was entertaining myself in the same way as the others, even some of my suitors were Christians. Step by step we were excluded from our previously normal life, and the Jewish youth began to mingle with people of their own only. First, I think that was in 1940, Jews had to hand in their wireless sets. The next step was that Jews had to move out of the town center; we weren't allowed to use the sidewalks and had to walk on the road instead. [The interviewee is referring to the introduction of the various anti-Jewish laws in the Protectorate of Bohemia- Moravia.] 8 We didn't tamper with the rules because we were afraid to be reported to the Gestapo by Czech Vlajka fascists. We weren't sure who was who any longer; first we thought about someone of being well-disposed, and finally this person turned out to be an anti-Semite. We stuck to the rules and stayed away from the town center.

During the war

My mum sold the goods from our drapery shop when my father was arrested at the beginning of World War II. Jews had to hand in all their gold. I don't remember exactly when it happened but once in the evening German soldiers came to check our place. We were threatened because my mum had hidden some fabrics from the shop at home. We used to have cushions between the glasses of the windows, it was stylish at that time, and my mum had made those cushions from fabrics from the drapery shop. The soldiers didn't find anything and were quite decent. Actually we didn't know much about what was going on, regarding the deportations because we were far from Prague. When we were taken to Terezin we didn't have any idea about that place. We found out how terrible it was pretty soon though.

In 1939 the rumor was circulating that the Russians were already coming to liberate Tabor. The Germans then organized raids and arrested a lot of Czech people, mainly Jews, including my dad. At first he was a prisoner in Dresden and then he was sent to Oranienburg. [Editor's note: There was a concentration camp in both Dresden and Oranienburg, the first was a subcamp of the Flossenburg concentration camp, and the second a subcamp of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.] He was used to smoke, drink good coffee and have a good meal, so he just couldn't bear it. They were also torturing people. My dad died in Oranienburg in 1940. What was interesting was that they sent us his urn from Oranienburg along with his clothes and all his other things including his denture with a gold palate. We also got the death certificate. There was still a Jewish cemetery in Tabor so we took his remains there. Then the cemetery was liquidated and since the urn hadn't been there for a long time we were allowed to remove it and take it to a Catholic cemetery. They had made a space for Jews near the cemetery wall there, and my dad's has remained there ever since.

At the beginning of the war I fell sick and couldn't do as much as before. The pain started in 1939. The doctors said that it was the appendix and sent me for surgery. But the pain remained, and in 1940 I was diagnosed with a tumor on the ovary. I had my last period in Terezin. But we got food with quinine in it there, and it stopped the menstruation of most of the women in the camp.

It was terrible when we were deported to Terezin in November 1942. All the Jews from Tabor and the surroundings received summons for the transport to the ghetto from the Jewish community in Prague. We were put into the school building. There were about a thousand people crowded there. We arrived there in the evening, didn't get anything to eat and slept on straw mattresses for one night. Early in the morning we were taken to the train so that no one would see us. It was bitter cold. We knew we would go to Terezin but had no information about the place. Until then we hadn't suffered physically because my mother had sold all the goods from the shop, so we had had assets to live on.

I lived in L-309, a kind of youth hostel for girls. It was a single-storied house, and I shared a room with twelve girls there. I remember that the cembalist Zuzana Ruzickova stayed in the room next door. This house originally belonged to a woman who was also kept in Terezin. I worked in a laundry situated outside the ghetto. My mum took care of a 5-year-old boy called Kaja. Kaja was there with his father only. They somehow became our relatives. My brother worked in agriculture first, and then in the Kinderheim [children's home]. My grandfather died a month after our deportation to Terezin, and my grandmother died a month after him. The burials in Terezin were the same for all people. The corpses were burnt, and the ash was thrown into the water. We were allowed to take part at the funeral. We said a prayer and received my grandparents' clothes.

In the evening we got a piece of bread for dinner, for lunch we usually had lentil soup. Sometimes we also had millet pudding, which I have been cooking ever since our liberation. It's kind of a piety for me. I say that this is a memory of Terezin I keep. I like millet pudding, but I prepare it better because I cook it with milk, and in Terezin it was only cooked with water. Another time we had a yeast dumpling with special black sauce, which was very tasty. It was sweet and made from black coffee residue mixed with bread and some margarine. I was trying to prepare it after the liberation, but it was never as tasty as it was in Terezin. Sometimes we also had stuffed cake. My mum didn't like the dumplings so I swapped it with her for the cake. We drank water.

Once we were listed for a transport to an extermination camp, and Viktor Kende, a friend of us, helped us to get crossed off the list of people to be transported. In December 1943 we were listed again, just my mum and I, but Viktor couldn't help us this time. My brother and Jiri weren't on the list for this transport but they enlisted themselves voluntarily, so they went with us. Jiri's parents had already gone, but he had been sick at the time so he hadn't gone with them.

We didn't know where we were going to. It turned out to be Auschwitz. We spent about two days in cattle-trucks. In the end the doors were opened, and we saw the notice 'Arbeit macht frei'. [German for 'Work make you free', the words inscribed on the infamous gateway to the Auschwitz concentration camp.] Germans were shouting, and we had no idea what was going on. We had expected that we would be going to a place similar to Terezin. In Auschwitz we were in the so-called Family Camp. [The so-called Family Camp established in September 1943 was an area reserved within Auschwitz for Czech Jews deported from Terezin.] I was carrying barrels with soap, Mum still took care of the small boy who was gassed along with his father later. My brother worked with children in the Kinderblock [children's block] with Freddy Hirsch. [Freddy Hirsch, originally from Austria, emigrated to the Czech Republic before World War II, and was known as a great Zionist and sportsman. In Terezin he took care of children and was very popular among them.]

After half a year I was moved with my mum to forced labor in a Frauenlager [women's camp] near Hamburg. We stayed there for four days, and it was very bad. Once they left us kneeling down the whole day. Then we went to Harburg, which was a suburb of Hamburg, where we stayed in some barns and went to Morburg, a huge oil factory, by boat. We were rebuilding the factory. When the factory was supposed to be reopened air raids started and it was destroyed again. After that we worked in Neugraben [a subcamp of the Neuengamme concentration camp], where we were scavenging through debris; and in Tiefstack [another subcamp of the Neuengamme concentration camp] we worked in a brickyard. There wasn't enough food. In the evening we got a quarter of bread and my mum said to me, 'You must not eat it all, you have to save half of it.' So we were saving part of the bread but our co- prisoners stole it. From then on we were eating everything at once.

Post-war

In 1945 we were taken to Bergen-Belsen, which was a terrible place. I remember tents full of corpses. We were liberated from there by English troops on 16th April 1945. Some women from Czechoslovakia paid for the bus to get their men back home. But their men weren't in this camp. I remember my mum telling me that there was a bus going home and that we had to take it. It took us about two days to get back. The bus was old and just about to fall apart. At night we slept in the open air. I don't remember this personally because I was sleeping but my mum said that our two drivers attacked some Germans at night, killed them and stole tires. Then we came to Prague where we stayed at some first-aid place for prisoners in the beginning. Afterwards we decided to return to Tabor.

We had friends in Tabor called Macaks, and my mum sent them a letter saying that we were alive and asking if they knew anything about Jiri and my brother. She also wrote that she was looking forward to stuffed cakes. When we arrived in Tabor we met our friend Mr. Kratochvil, who had a furniture factory, and he offered that we could stay with him for a while. I didn't know that Jiri was already in Tabor. He didn't know that I was alive either. There was a bakery in Tabor, owned by a family called Lapacka, and Jiri went there to buy bread. Mrs. Macakova was in the shop at the same time, and she told Mrs. Lapackova that she had received a letter from my mum. That's how Jiri found out that I was alive. He didn't know anything about my brother. They had both been transported to Schwarzheide concentration camp in June 1944. Jiri said that Rudolf had been too weak to join the first death march and that he stayed in the camp. He then joined the second march but he was too weak. Jirka Frankl wrote to us that he was with him and that Rudolf had some cigarettes and wanted to change them for some food but without success. All the prisoners were weak and Rudolf didn't want to hold them up, so he sat down on the side of a ditch and was shot.

Back in Tabor we received a large four-bedroom apartment in town from a Jewish family called Mendl. Jiri and his brother Richard received an apartment, too, and Jiri's cousin, Marta Navratilova, was staying there with them for a while. Our belongings had been hidden at different people's places, and we got some parts of it back. We had troubles with one furrier. He had a concave stairway in the house, and my mum had hidden a lot of things there, including carpets and original paintings that my dad was collecting. My mum had made a list of all the things she had actually put there. When we wanted these things back he made difficulties and, for example, just gave us the frames without the paintings. He kept saying that the Russians had confiscated everything, and my mum got upset about his lies and brought him to trial. She won, and he had to pay us 30,000 crowns. He robbed a lot of Jews and made money on them. Except for this we had a very warm welcome after coming back. We also had belongings at some of my friends' who returned everything to us.

Jiri and Richard decided to rebuild the confectionary warehouse. We didn't have very much money but the Orion confectionary factory gave them a credit in the name of their father, and so we got started. I worked with them, and my mum was at home cooking for us and doing the housework.

In April 1946 we had a double wedding, me and Jiri, and Richard and Marta, who was Jewish and had lost her husband during the Holocaust. The wedding was on the same day a year after I had been liberated. I didn't realize until I received a telegram with congratulations from my former co- prisoners.

We shared a house with Richard, his wife and their two daughters, Marcela and Zuzana. was religious and often went to the synagogue. He came to Prague on Jewish holidays. His girls didn't feel Jewish. We had the warehouse and sold goods to small businessmen. We had a Tatra and an assistant driver. We were successful, but we worked really hard for it. I was in the shop or in the office every single day. When communists nationalized the warehouse in 1948, I was actually glad that I got rid of it.

My mum had an apartment in Tabor and lived there with her nephew, who had returned from the camp alone. His name was Harry Kraus, and he was born in 1933. He was the son of my mother's brother Frantisek. Due to the war, Harry had lost several years of compulsory education. My mum sent him to the gymnasium in Tabor after the war, so that he could complete his studies. However, he cared more for girls then for his studies, so she organized an apprenticeship for him in some weaving factory in Ceska Trebova in 1948. He didn't feel comfortable there either, and in the end some friends persuaded him to go to Israel.

It was legal emigration, organized by a man, whose name I can't remember. A group of young people, who had survived the war and stayed alone, went to a kibbutz called Hachotrim. The kibbutz was near Tel Aviv and close to a Czech kibbutz named Masaryk. Hachotrim was mainly an agricultural kibbutz; they were breeding hens there. Well, Harry was kind of a wild person and wasn't able to keep up with the discipline there, so he left. He spent some time in Haifa and then moved to Tel Aviv, where he worked in some laundry.

Harry got married soon after he arrived in Israel at the age of 19. His wife, Lilly Kleinova, was two years older than him. Lilly originally came from Slovakia, her family ran a quarry there. She couldn't have children, so they adopted a three-month-old boy. My husband and I visited them in 1969 for a month, and Harry tried to persuade us to stay for good. But firstly I didn't really like it that much, and secondly we didn't want to emigrate because of my mum, who was already severely sick. We could neither take her along nor leave her. My husband loved my mother, and they had a very nice relationship. We made a deal that we would come back to Prague, and after that we could eventually try to figure out how to manage the aliya. When we returned, the borders were closed, and I'm glad we didn't stay there. My mum died in Tabor in 1962. She had a civil burial. We stayed in the old house but were only three people, so in the end we sold the house and moved to two apartments.

We had a few friends in Tabor, but we were mostly in touch with our own families. Richard and his wife were older, so their daughters spent most of the time with us, and we also took them on vacations with us. We often went to Bulgaria for vacations and later to Slovakia. We also spent some holidays in Zelezna Ruda at a cottage, which belonged to the company I worked for. After the events of 1968 [Prague Spring] 9, Marcela moved to Prague, and Zuzana emigrated to Switzerland.

My husband began to work in a textile factory in Ceske Budejovice in 1948. He was diligent, worked his way up and soon held a distinguished post. However, some communists didn't like it because he used to be a businessman, and they fired him during the program '77.000 persons to manufacture' [the program was actually called 'Action 77,000'] 10 so he had to start all over. There was a silicone fiber production factory in Tabor, so he went to work there with a friend of his. He started as a manual laborer, it was nonstop work, including Saturdays and Sundays. In the end he worked his way up, but again he was told that as a former businessman he could be no more than a foreman. Jiri said to the director, 'Comrade director, you say I cannot be production planner but you let me be a foreman who can influence hundreds of people?' He did become a foreman but slowly worked his way up again, and then he was in a really good position until his retirement in 1981.

I started to work with Jednota, which was a collective consumer co- operative, in 1950. In the beginning I was an assistant in the administrative department, but I worked my way up to the head of the financial department. I worked there for 30 years. I was never voted to become a member of the company union, although I worked there for ages and had a leading position. I was Jewish and my husband a former businessman, and that wasn't the best 'qualification' under the communist regime. But we cared little about it. I continued working there for two years after I retired at the age of 54.

We celebrated Christmas. We knew that there was Pesach and Chanukkah and so on but we didn't celebrate it. We ate matzah on Pesach, but I didn't do any special cleaning at home. We didn't observe the high holidays. Most Jews from Tabor, who had survived the war, had moved away afterwards. We used to go to Prague but only for memorial services to remember relatives who didn't survive.

When the Russians came in 1968 we were both surprised and disappointed, just like everyone else. Their tanks drove into Tabor, and Jiri wanted to go to the square but I was scared. However, I was more afraid to let him go on his own, so I joined him. The streets were full of people but nothing happened. The tanks must have come to Tabor by mistake because people had moved the road-signs giving directions to Prague, so the Russians sometimes ended up somewhere else than they planned. At that time we had visitors, young relatives of Jiri staying with us, the children of his cousin Marta Navratilova: Jirka and Vera Navratil and their partners were spending their vacation in our region. Vera was canoeing with her boyfriend, and when the tanks were on the bridge they did a very stupid thing: They started to throw potatoes from the canoe towards the tanks. Fortunately nothing happened, and there was no shooting. In Tabor the situation wasn't as tough as in Prague. Well, we were checked at our workplaces, so that they could see if we were loyal enough and if we agreed with the invasion of the Soviet army, but that happened everywhere.

I helped at the local organization of the Union of Anti-Fascist Fighters. I didn't feel any anti-Semitism after World War II. We have been registered with the Jewish community in Prague since 1945. There was no Jewish community in Tabor, so we were living there as the almost only Jews and didn't bother anyone. I had a simple and nice life with my husband. We didn't have any children. We were neither rich nor poor, and we weren't involved in politics. We have always lived modestly and what we had was enough for us. We weren't persecuted in any way.

I wasn't very excited about the Velvet Revolution 11 in 1989 and the time after. I'm not a fan of Vaclav Klaus 12 or Vaclav Havel 13. I lived under capitalism before so I know that those who don't work won't eat. And that's what people couldn't understand. They thought that if they jingle their keys on a square everything would just easily fall into their arms. [Editor's note: During the Velvet Revolution people went out on the street and jingled their keys, in imitation of the last school bell before school is over, as if to say that the days of the communist regime were numbered.] And Mr. Klaus was supporting them in this idea. My husband died in Tabor in 1999 and had a civil burial.

I moved to a Jewish pension in Prague a year and a half ago, and I like it very much. No one is really religious here but we get together on Jewish holidays. I have a nice pension so I am not really dependent on the assets I receive from different funds for Holocaust victims. It's nice to get that money, but I'm not upset if the payment is delayed unlike some other people.

I was and I am a believer. I believe that there's someone who directs our life. I think God is 'human', and he's not only there for Jews or Christians but for everyone. However, I cannot imagine that I would ever pray. I believe that when someone is born his destiny is already written. What happened to us probably had to happen. Our fate is to be Jewish.