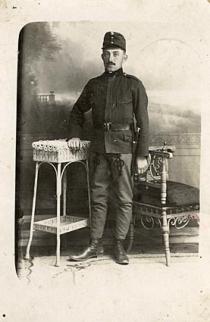

In this picture that's Imre Diamantstein, my husband. It was taken in the fall of 1944. He was 29 when he got back from forced labor. You can see his clothes, he came home in these rags. Probably that's why he wanted this picture taken, I got this picture from him and kept it.

The picture was taken in the Kantor photo studio in Marosvasarhely. The photo studio functioned for a short period even after World War II, and there was a restaurant and some stores next to it, but those were demolished and some flat blocks have been built instead. Currently the Arta [Art] cinema is there, as well as some stores and apartments.

My husband was in a terrible place for forced labor, they took them to the swamps of Pripet, which, as far as I know, is in today's Ukraine [Editor's note: Also known as the Pripyat swamps, it is the largest swamp in Europe, covering Southern Belorussia and Northern Ukraine. On 12th August 1941 6,526 Jews accused of theft were shot there. They wanted to sink the women and children into the swamp, but it turned out it wasn't swampy enough. www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/Pripet.] He was there with Naci Rosenblatt, and they marched over a thousand kilometers, and, almost miraculously, he came back safe and sound. It was in November 1994, at the age of 29, when he got home in rags from forced labor. He had a near touch, even though he was a slim figure, but it looks like he was very resistant in the extreme misery. Unfortunately all those who came back from that hell stopped being religious, because the holidays were family holidays and they had no families anymore, none of them had.

My husband was originally from Deva, and his father, Jakab Diamantstein, was a merchant, but I didn't know my father-in-law personally. They were three brothers, the elder brother, Miklos, the younger brother Istvan (Pista) and my husband, Imre. My husband graduated law school in Kolozsvar and worked here in Vasarhely at a law office as articled clerk, in Dr. Gusztav Hirsch's law office, until he was taken to forced labor. My husband's family was very religious, moreover, my husband used to pray even at home each morning, following the prescriptions. They weren't Orthodox Jews, but they were observant and used to go to the Orthodox and not the Neolog synagogue. They had no payes and such, but all the Diamantsteins, because there were many Diamantsteins in Vasarhely, were all religious.

My father went first to Bucharest, to his older brother, and he came to Vasarhely from there. And he got a job. At first, as a lawyer, he got a job at the court as judge, but the wage he got there wasn't enough to help him subsist. When I married him he had an office with a lawyer called Bela Harap, opposite to the today's maternity, in a corner building. But this only lasted for a short period, because it was closed down during the nationalization. Then he got a job in the timber business in Vasarhely and retired from there. This company he was working at had several names, because it was reorganized many times and they had authority over the entire Csik [region] for a period, then not - this was the period of the regional reorganization, when the regions were transformed into counties in the 1960s. [Editor's note: Zsuzsa Diamantstein refers to the regional reorganizations from 1952 and 1968]. In the last period he worked at the IFET (Intreprinderea Forestiera de Exploatare si Transport) [a timber trading company] in Regen, because a manager called Florea, the manager of the local furniture factory, advised him to do so because he was approaching retirement and if he transferred to IFET, he would have had a larger pension. So he transferred there, and even after he retired he still went to work there voluntarily. He was a very active man, he hated idleness. When he finally stopped working, he typed state exam works for students. He always found something to do.

Music was his passion, classic music. My husband learnt to play the piano in Deva, but there was no chance for a career in music in a middle-class family- that was not a career, rather a bohemian thing, they all urged them to choose a serious profession [this was the view then]. So he became a lawyer and since he was a very thorough man and always learned and did everything perfectly, that is very thoroughly, he was very good at it and became a very respected lawyer in Marosvasarhely. We had a piano for a while, but one day we sold it because we needed the money to support our children, who were university students. But we were amongst the first who had a record player, a trashy old Soviet record player, and we also bought many records. It's true I learned to play the piano and I grew up with music, but I really learned the music [to qualify it] beside my husband, so I could tell the difference between a very good and a very bad piece. While we were still a young couple and our children were still small, we used to go all the time to symphonic concerts, theatres, cinemas, and there was no performance we didn't see.