Rifca Segal

Botosani

Romania

Date of interview: August 2006

Interviewer: Emoke Major

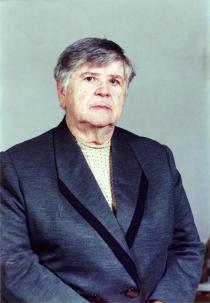

Mrs. Rifca Segal is a very friendly, cheerful person, who takes great pleasure in talking to people. My first interview with her took place at the Jewish Community in Botosani. But she requested that our second meeting should take place at the city’s Public Garden, where she is keen on going, even though she has difficulty moving about because of her weight. She also invited me at her place – a two-room apartment in a block of flats, furnished very modestly, decorated especially with ease-of-use in mind –, and I must admit I also enjoyed the backgammon we played together. When we said good-bye to each other, she also gave me a porcelain stork as a present.

My family history

Growing up

During the War

After the War

Glossary

My grandparents from my father’s side were Iosif and Perla Calmanovici. They lived in Sulita, in the county of Botosani. [Sulita – former borough, a village at present – it is located 35 km south-east of Botosani.] They were merchants in the borough of Sulita, which was a small borough where the majority of inhabitants were Jewish – there were around 300 Jewish families. It was a nice, commercial little borough, all the peasants came from the countryside and bought merchandise here. My grandparents had a store where they sold haberdashery, shoes, perfumes, small ware. They brought the perfumes directly from Paris. They came in small parcels – smaller than a suitcase – by mail, and my grandparents paid for them on delivery. It was Bob Germandre, Chypre fine Cologne. Nowadays the brands are completely different, and they are expensive, it costs millions of lei to buy a fine perfume. But it was affordable back then, you can’t even compare the prices

I didn’t even know my grandfather, I only knew my grandmother. My grandfather died in the 1920’s. He went to buy merchandise in Botosani – people supplied their stores by cart then –, and it probably rained heavily on the way back, he caught a cold which developed into a pneumonia and you couldn’t cure it back then – he died, poor soul. I think my grandmother was around 35-36 when my grandfather died, and it was her who raised the children, she ran the store afterwards. My grandmother was a rabbi’s daughter. Her father was a rabbi in Radauti. But I don’t know his name – he was my great-grandfather. After my grandfather died, she kept running the store, as the children helped her. Then my father took over. My grandmother from my father’s side lived with us. I loved her immensely, and I can’t go to see her grave, for she had a daughter in Galati, and she went to visit her, and that’s where she died in 1946. I went to see her grave only once.

My grandmother from my father’s side had a sister, her name was Haia Liba – Hai’ Leba in Jewish –, who married a certain Rotaru. They livd in Sulita as well, he was a carpenter. They had several children: Iosif, Bella, Max, Rahel, Elca, Roza… They were around 8. The girls were housewives, they got married, all of them. You know, parents didn’t formerly want their daughters to have jobs – they married them. It was the men who had to have a job. Iosif – his Jewish name was Iosl – was a carpenter, just like his father. Every single one of them lived in Sulita, then they too were evacuated 1, relocated to Botosani during World War II. These cousins of my parents lived in Botosani for a while as well, but eventually all of them left to Israel, absolutely all of them.

My grandmother told me that she had 13 or 14 children. A very large number. Poor soul. She wasn’t allowed to have an abortion. If you’re a religious person, I think you aren’t allowed to do that, regardless of your religion. They married at 15, 16 back then, that’s how it was. But in the end, 4 of them lived, whom I have met: my father, two other brothers and a sister. The eldest was Ozias, followed by Ana, then my father and then Marcu. The others died. Perhaps they were older than them.

Ozias Calmanovici got married in Falticeni with a rich girl – her name was Fany. He got a rich girl and a cruel fate. The legionnaires 2 took everything they had. They had a manufacture store in Falticeni. They too were relocated to Botosani, and then they left to Israel right after World War II, the whole family. They had 4 children: Iosif – Ioji –, Paul, Ada and Ietti. 2 gaughters, 2 sons. They had 4 children, but one of them, Iettica, poor soul, died 6 years ago [in 2006], and now only three of them are left.

My father’s sister, Hanah Kizbraun, a noble woman, got married in Galati. Her husband, Moses Kinzbraun, was an accountant, she was a housewife, and they had an only son, Ioji [Iosif], who is an engineer. After finishing his studies, the boy was given a position in Bucharest, he got married there to a girl from Bucuresti who studied chemistry. I visited them many times. And after they settled there, they brought their parents to Bucharest. They found them a studio flat to rent – back then you rented them, you couldn’t buy them –, and they settled [moved] to Bucharest. My aunt was the first to die, then my uncle died, and that was the last I heard o them. Ioji is now in Haifa, and he also has a son who is a doctor in Jerusalem.

Also, one of my father’s brothers lived in Focsani, his name was Marcu Calmanovici, who also married to a very rich girl – that’s how it was back then – from Falticeni, her name was Bety, and he opened a large store in Focsani selling manufacture products and ready-made clothes. They had no children. He was arrested during communism on the grounds that he owned gold coins. He was denounced for owning gold coins, they searched his house and arrested him. He went to prison as well, but since they took the gold coins away from him, he received a light sentence. His wife died in Focsani in 1992-1993, after which he left to Israel. Let me confess another thing: he had a sweetheart from his youth, and she go married, had a daughter, but they continued to write each other secretly, through third parties. And when she heard that his wife died, I’m not even sure a year passed since she died, she came and took him to Israel. They were old by then, but you see what youth love means? I visited them in 1993, when I traveled to Israel, they lived in Naharia, they invited me to dine with them. She was very nice with me, and she gave me gifts, for she saw he loved me very much. He was my father’s brother, he didn’t have any children, and he loved me very much. And he was happy he could invite me there to see him. I think he died in 1994.

As for the others… I have no news of them anymore. That’s all I know, that one of them died in the war [in World War I]. There is also a monument at Mareata Sulita with all the poor people who died in the war, and Calmanovici is listed among the heroes who died. His name was Haim Avram. He died in 1917, my grandmother brought him to Botosani, he is buried here. And I can’t find his grave. I know the alley, the number, and the cemetery caretaker can’t find it. I wanted to build him a very simple monument.

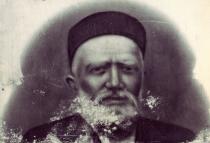

My father’s name was Aizic, but people also called him Mose. His Jewish name was Mose, but his official name was Aizic. My father was born on August 8, 1900. I loved him very much, and each year I knew when his birthday was. He had no higher education. In small towns, you didn’t need higher studies if you were a merchant. If they earned good money, merchants didn’t go to the faculty. My father only graduated primary school, and so did my mother. If they were rich, why would they need schooling? My father wanted me to become a pharmacist. He wanted me to be a pharmacist in Sulita, I should own the pharmacy, and he should supply it.

The name of my grandfather from my mother’s side was Iancu Moise Mattes, and my grandmother’s name was Tauba. She was a housewife and my grandfather had a store in Sulita, too. That’s how it was in small towns – trading was the occupation of Jews. There were also Jews who dealt in buying and selling cereals, there were Jews who raised sheep. People said Jews weren’t good at agriculture – I must be objective. There were Jews who owned land, but they didn’t toil it themselves, they leased it to other people. There were 2 brothers. Their name was Blumer – my parents were friends with them – who were partners and had 2 mills, but they were no rudimentary mills, a windmill and a water mill – for there was a river there, but don’t ask me the name of that river, for I no longer remember. Such were the people of Sulita, and they were doing fine, they were rich enough, even very rich. There were also very many Jewish handicraftsmen in Sulita. There were shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, tinkers… all kinds.

This grandfather had a manufacture store – fabrics only. I know that my grandfather from my mother’s side bought merchandise from Iasi. My grandfather died in Sulita, he is buried there. I really want to go to Sulita, to visit his grave. He died around 1934-1935, for we went to Falticeni to a wedding in 1936, and grandfather was no longer alive. After my grandfather died, the grandmother from my mother side lived with her daughter Branica at first, at Frumusica, then she came to Botosani together with them. And then, after the daughter died, when uncle Heinic married his second wife, my grandmother left to live with my mother’s other sister – who is living in Israel at present, but she was still living in Botosani back then – as the grandmother from my father’s side lived with us. The grandmother from my mother’s side died here, in Botosani, in 1961, I believe she was 80 or 81. She is buried here, I go to visit her grave.

My mother had 2 sisters who were younger than her. I know that she also had a brother, who died when he was little. I don’t even know what his name was, I don’t know anything about him.

Branica was one of my mother’s sisters, Brana Mendelovici – born Mattes, changed her name to Mendelovici after she married. Her husband’s name was Heinec Mendelovici, and they had 2 sons: Froim and Iancu. Froim was the same age as my younger sister, so he was born in 1937, and Iancu was a few years younger, I think he was born in 1940. They lived in Frumusica, my aunt married a man from Frumusica – near Sulita. [Frumusica is located 27 km south of Sulita, 39 km south-east of Botosani.] My uncle was a merchant as well, he too had a manufacture store, he sold shoes in Frumusica. [When they came] In Botosani, they probably had gold coins, I couldn’t say for sure, I don’t know about that, they kept it a secret from me, and they bought sheep, they kept them close to Botosani. And he was more well-off than us, and he helped us. My mother’s sister, Branica, died in 1946, and after that my uncle got married again with another woman named Augusta, a very nice woman. And Heinic and Gusta, his new wife, left to Venezuela with their 2 sons, I believe it was in 1953 or 1954. Gusta had brothers there who owned gold mines. And I believe they paid a fortune, I couldn’t know how much they paid. For you had to pay for the retrieval [that is, you paid in order to leave the country]. And I so wanted to know how much they had to pay, but I don’t know to this day. [Ed. note: It is not likely that Venezuela paid Romania for the Jewish emigrants, rather the people paid a sum so that the Romanian authority let hem leave. “By 1950, in spite of immigration restrictions, there were around 6,000 Jewish people in Venezuela. The biggest waves of immigration occurred after World War II.”]. And they had another son in Venezuela. But their third son left to Israel, he didn’t want to live in Venezuela. He’s not relative of mine, I have nothing to do with him, yet I visited him in Israel.

And I have another sister of my mother’s living in Israel, she’s still alive. Her name is Rifca Peisich. She got married here, in Botosani, in 1944, her husband’s name was Iancu Peisich, they left to Israel together. This aunt of mine is very old, she turned 88, may she retain her good health. She calls me on the phone every day. And we don’t have something to talk about every day. But: “Are you well?” “Are you well?” That’s it. So that we hear from each other. Fate made us drift apart. She lives in Rehovot, it’s such a nice city… I’ve been there. She had an only daughter, who died of cancer when she was 56. Her Jewish name was Reiza, her official name was Rozalia, but we all called her Rodica. She had a daughter who is alive, may she retain her good health, her name is Monica, who has a child herself. So my mother’s sister, Rica Peisich, is a great-grandmother. And my aunt is living with her son-in-law, and the son-in-law – it’s only natural – brought another woman in the house, but she is treating her very well. Yet she has heart-related problems, and her eyesight isn’t that good anymore.

My mother was born on March 3, 1903. People called my mother Anuta, but officially, her name was Hana Lea.

My mother had a dowry, my grandfather was rich, richer than the grandfather from my father’s side. And do you know how it was formerly? If the dowry were large, cousins, relatives would marry each other, so that the fortune wouldn’t be estranged – such was the notion. But my mother – it’s not the fact that she was my mother, yet – was both very beautiful and very smart. And my parents were cousins. You wouldn’t believe it, if I told you. My father’s mother and my mother’s father were brother and sister. And they weren’t allowed to get married according to the laws that were in force back then, during the rule of king Mihai. [Ed. note: The ruling of the Romanian kings during these decades is the following: King Ferdinand I. 1914-1927 3, King Michael 1927-1930 4, King Carol II. 1930-1940 5. After King Ferdinand’s death in 1927 the Romanian Monarchy goes through private and political crises]. They needed a royal exemption in order for them to get married. For the fact that they were cousins was public knowledge in Sulita. If this were to happen in Bucharest, the people at the registrar’s office would have been none the wiser. And then my mother wrote a complaint – or her parents did, I can’t say for sure – to the king, and she had to base her argument on the fact that they had lived together. Formerly, sleeping with a man before getting married – oh my, it was a crime. To make love – I won’t say to have sex, for I dislike saying that – before the marriage, oh my, it was serious. Especially in a small town. And they were so chaste – that’s what they tell me, I wasn’t born at that time. And that’s how their marriage was approved.

And my mother had a dowry, she was richer, and they bought a nicer, more elegant house than my grandparents’, they had more money to invest into the store. My mother was a housewife, and my father was a merchant. My father inherited his father’s and grandmother’s store, he continued to run their store. They sold haberdashery, shoes, perfumes, small ware, everything. My parents bought supplies from Botosani. There were merchants who came from Botosani with cases of merchandise, who recommended you products, and you chose what you wanted.

My father’s handwriting was extraordinarily beautiful. He could also write a German gothic style, which I think nobody could write at that time. The letters had certain embellishments characteristic of each letter. He liked it very much. He was a self-taught man, for he didn’t go to any faculty. He drew the shop signs himself, he did such a good job of it. For you placed a shop sign outside the store, o a piece of painted iron plate. The store didn’t have a proper name, the iron plate read “Calmanovici’s.” I can picture it now. On a black piece of iron plate my father wrote the name in white paint, and my mother, in order for someone not to cast the evil eye on him, bound a red ribbon around his arm as he was painting the sign. And I used to laugh… She loved him very much. And they lived a very nice life.

My parents got married in 1927, and I, Rifca Segal, was born in 1928. Officially, my name is Rifca, they named me after a great-grandmother, the mother of my grandmother from my mother’s side. But people call me Rica, as Sulita’s county chief – his name was Hotupasu – had a daughter whose name was Rica. And my parents were very good friends with the county chief.

My brother was born in 1930, people called him Ioji, but, officially, his name was Iosif. There was this custom, which I see that people in Israel don’t observe anymore nowadays, of naming people after the dead. People even paid money in order to have someone named after a dead person. [Editor’s note: The custom of paying to a woman to name her newborn after a dead was common. Giving the dead's name to the newborn was even considered as a mitzvah (ritual commandment or generally any act of human kindness.] And so both my aunt, and my uncle from Falticeni, and my father named their son after their father.

My brother didn’t go to the faculty. He worked as an assistant in the laboratory of the Botosani mill. At first, he worked there without having any schooling, and they sent him to Iasi to a school for laboratory-assistants to follow some specialization courses and he specialized. He was held in very high esteem. The courses lasted 3 years, but he didn’t stay there all the time, he came home, he went there again. He wasn’t married. He had a disappointment in his love life. He was engaged to be married. His fiancée received the approval to leave to Israel with her parents, her parents didn’t want to leave her here all by herself – for they weren’t married, they were only engaged – he was going to leave as well, his request was denied, which is to say his departure wasn’t approved. This happened in 1959. Not only his request was denied, people’s requests were denied by the dozens. And he didn’t leave, after all. But he was the only one of our family who requested permission to leave to Israel, for the sake of his fiancée. He lived in Botosani as well, but we didn’t live together. He died 2 months ago, on June 5, 2006. Ah, how ill he was…

I also had a little sister, Rozica, who was 9 years younger than me, she was born in 1937. She died in 1947, she was almost 11, she had just graduated 4th grade of primary school. Had we found some sulphamid back then in Botosani, perhaps we might have saved her. She contracted typhoid fever. This was after the war, it was that drought, we had no money…

It was nice in Sulita. We led a good life there. I miss it even now, as we led a very good life there. We had a house with several rooms, a cellar, an attic, a courtyard, and a barn in the courtyard. It was a brick house, like they built them in small towns, one next to another, adjoining. If, God forbid, a fire had broken out, all of them would have burned to the ground. In front, in the same building, there was the store, which was large enough, and then there was a kitchen to one side followed by three rooms, in the back. Small town kitchens had a fireplace with a cooking stove and an oven. It was made either from terracotta or from bricks. And when my parents renovated the house, they modernized it, they built a terracotta fireplace in the room in the middle. They left the one made of bricks in the bedroom as it was. Besides, it was very nicely built, with pillars. It was a house with an attic, a cellar. We dried laundry in the attic, and stored the food in the cellar – for we didn’t have refrigerators back then, we didn’t even have electricity in Sulita. We used lamps and lamp oil for lighting purposes. But we had a nice lamp, with silk. And of course, the toilet was in the courtyard. We didn’t have a bathroom in the house. Even though my grandparents from my mother’s side had a fountain in the courtyard, and they drew water from it using a water pump, and they built a bathroom inside their house. They had a bathtub, and they had a cauldron in which they drew water from the fountain through pipes, it reached the cauldron, the lower part of the cauldron – like in a terracotta or zinc stove –, had a compartment where you placed firewood, you lit the firewood, and the water was being heated. And it was very good, I used to go there myself to take a bath. For at home, my mother bathed me in a small tub. That’s how it was in Sulita. But she added Chypre cologne from Paris to the water. But she bathed me in a small tub. That’s how it was, and it was fine. Our life was so good! Had they not evacuated us, it would have been very well.

When I was just a baby, I was sleeping in my parents’ room, where I had an iron crib; it was elegant, painted white, and it had painted angels at the head of the bed – I take pleasure in remembering that. And then it was my brother who slept there. When I grew up, after the age of 9-10, I slept in the middle room on a sofa. But they placed a carpet on the wall, so that I wouldn’t touch the wall.

We played domino and “car” in Sulita. “Car” is a game that you play like this: you draw a rectangle on a piece of cardboard, another rectangle inside it, yet another rectangle inside it, you draw lines connecting them to create a labyrinth, and you placed a button or a coin, and you had to reach the center with the button or coin. You moved, and moved, and you tried to move only along the lines. But it was very difficult to manage not to jump over the lines. You played individually, but you played against someone. If you didn’t succeed, you didn’t win, and then the other one took his turn, your opponent, and if he succeeded, he won. I liked that game very much. I also liked domino. Even my parents stayed indoors on winter evenings, when it was cold and frost, by the fireplace, and played domino. They played separately, while we did our homework.

My mother, may God rest her soul, was very severe. She established things around the house, what needed to be done, what needed to be bought. Well, she was harsher, may God forgive her. Whereas my father was meeker. I loved him immensely. I loved my mother as well, but it was different with my father. And do you know how parents were in former days? They loved me very much, but they didn’t spoil me. My father called me using a diminutive, Ricola instead of Rica, but he wouldn’t caress or kiss me. Yet I could feel he cared for me. So did my mother, but my mother, may God rest her soul, was more distant. She would yell at me, if something didn’t agree with her. I think my father never yelled at me as long as he lived. Mother was severe with me. When I was little, she even used to beat me. But it was for my own good. But when I got married, she washed our clothes at her place, and she brought them over already ironed, and she had the keys to our front door and wardrobe, and she put the clothes in the wardrobe. She cooked for me, I sometimes didn’t have the time to come and get food from her, and she brought me the food home. As a mother would, no doubt. But she never caressed me, she never told me “my dear,” or something like that. She was more distant, but she was very honest.

I loved the grandmother who lived with us immensely – the grandmother from my father’s side. She was very religious, but modern. Just like my father. My father was religious. But a conductor came to Botosani, his name was Weber, he performed opera shows there, operettas, ballet, and my father used to attend, he liked it. I couldn’t conceive going to see them without my parents, and I bought tickets for them as well. And you know how ballerinas… And I had a friend who went with us as well, and she used to say: “Mr. Calmanovici, do you look at naked legs?” Well, he was both modern and religious. So was my grandmother, too. I went to school at the Jewish High School, and afterwards this high school was even mixed. And boys came to see me, my grandmother let them in, offered them a treat. So she was both modern and religious. And my mother was more in charge of the store. And that’s why I loved my grandmother very much. Oh my, how I loved her! She loved me very much, too. I loved my mother very much as well, how could I not love my mother, but she didn’t have time for me.

My mother had separate dishes for milk and meat. My grandmother was there, to see to it… of my, did she see to it! She was quite something, poor thing. When I grew up, I offered my opinion myself [on Jewish traditions]. But my oh my, my grandmother observed… Was I allowed to speak my mind in these matters? Do you know how she called me? ‘Bolshevik.’ For she knew Bolsheviks didn’t observe religion.

My mother took the fowl to the hakham to be slaughtered. And here, in Botosani, my mother, poor soul, used to run with the basket full of fowls – it wasn’t far –, and slaughtered them at the hakham. For instance, if you take the liver out, and it is stained, you have to throw the fowl away. The whole fowl, not just the liver.

My mother went to the ritual bath, I was there with her myself. The ritual bath in Sulita was very rudimentary, it consisted of bathtubs that were placed one next to another, and if you went to the bathroom, you undressed in front of women. But haf of it was for men, half was for women, there was steam as well, and also a mikveh. There wasn’t a separate mikveh for women and one for men, just one, but they took turns going there. I think they changed the water, you couldn’t do it otherwise. But this wasn’t for washing purposes, it was a ritual tradition, holy water. [Editor’s note: Mikvah or (mikve) is a ritual bath for the purpose of ritual immersion required by biblical regulations after ritually impure incidents (e.g. sexual activity, menstruation) have occurred. The word mikvah means a 'collection', generally a collection of water. The water has to be "living water" such as springs or groundwater wells. Full immersion in the mikvah nullifies most forms of impurity. It is not the water itself that purifies but the act of the immersion, which is subjected to detailed regulations specified in classical rabbinic literature.] But I never entered the mikveh, I have always been nauseous by nature. I only saw it, it was very rudimentary, with a cement pool, and a few stairs for getting into the pool, the water was up to the waist, but it wasn’t clean. My mother used to go in, for my father’s sake, as my father wanted to go to the mikveh. Here, in Botosani, the Jewish bathhouse had tubs as well, but it had separate dressing rooms. I went to the bathhouse in Botosani, I used to go to the bathhouse every now and then.

And let me tell you a story about the ritual bath. Women must go to the ritual bath before getting married. The brides, that is. I had to go there myself. There was a rabbi here, in Botosani, his name was Burstein, who had a small pool inside his house, a mikveh. It wasn’t large, it was like a whole in the ground, with cement walls, it had steps for going into it, he filled it with water – from what I could see, it wasn’t very deep, I think it went up to the waist –, and I was supposed to go in there. And I didn’t want to go in that water, I was nauseous. And there was this woman there, she was very mean. But I didn’t go into it. At the risk of not getting wed – God forbid! And I gave that woman 5 lei, and told her not to make me go in there, and she gave me a written proof for the rabbi, so that he would perform the wedding.

In principle, synagogues are all equally nice. And the one in Sulita had a place for keeping the Holy Scrolls, with plush curtains, with historical paintings on the walls. The one in Sulita had a balcony for women. Here, in Botosani, there is a separate room for women. There is also a balcony – you reach it by means of a circular staircse –, but it is out of use. In Sulita, you could go there every day, even in the middle of the day. Oh my, how I liked to go to the synagogue when I was little!

They say that the Sabbath, after Yom Kippur, is the largest Jewish holiday, which is celebrated every week. People observed the Sabbath very religiously. In Sulita, that is. People didn’t cook, didn’t do any laundry, didn’t work, didn’t sell things in the stores. You didn’t light the fire in the winter, there was someone who came – a boy, rather poor –, and he lit the fire for you. There were brick or terra cotta stoves, he made the fire, chopped wood, and came to put wood into the fire. And he was paid for it. You weren’t allowed to shred a piece of paper. All these customs were observed. And then, as general customs, there were separate dishes, separate dishes for meat, milk, not only on the Sabbath, it was an everyday practice.

Friday evenings were very nice. We ate on an oilcloth during the week. They set a tablecloth on the table on Friday evening. Married women lit candles and recited prayers. My mother lit candles as follows: 2 for themselves, 3 for the children – 5 candles. [Ed. note: It is customary to light two candles, although some families light more, sometimes in accordance with the number of children]. When my grandmother was still alive, she recited the prayer for her living children separately. I couldn’t tell you, I don’t remember how many candles she used to light. But they had yellow candlesticks. And we had 2 large candlesticks – I have them now, and I thought they were made from silver, but they aren’t –, they placed those at the head of the table, and on the other side, where my mother recited the prayer, they placed 5 candlesticks. After father returned from the synagogue, the 2 candles were lit, my father recited the prayer… like that, gravely. There were 2 loaves of bread and a knife placed on the table – the knife was placed between the 2 loaves of bread –, with salt, father would slice a morsel of bread, dip it into the salt, recited the prayer, after which he would eat that morsel of bread – only father, who recited the prayer. It was beautiful. In my home, with my husband, we didn’t have something like this.

Mother didn’t bake bread at home, she bought it. She baked when we lived in Botosani, but it wasn’t the case in Sulita, as you could buy it, it was awesome. The bread they had in Sulita, you couldn’t buy it in the heart of Paris nowadays. There were bakers, and such a white bread… Or when there was a holiday, especially on Purim, they added raisins to the bread. They baked kneaded bread for Saturday – the bread for Saturday was called challah. But the bread they baked during the week was very good as well.

And there wine at the table on Friday evening, father would first pour a glass, recite the prayer: „Bori pri agafen” [Editor’s note: Barukh ata adonai eloheinu melekh haolam borei pri hagafen. Praised are You O Lord our God king of the universe, Creator of the fruit of the vine.] –, would drink a sip, then he would pour into mother’s glass some of the wine in his glass, so that she could taste this blessed wine as well. Usually, it was traditional on Friday evening – for there was the Dracsani pond near Sulita – for us to eat fish, as meat jelly. And we also ate essigfleisch – boiled meat prepared with lemon juice, and dried plums were sometimes added to the mix. You boiled the meat, the vegetables – mostly carrots, so that it was sweet –, you sliced it down to regular pieces, as you do for meat soup, after which sour cherry preserve and lemon were added – lemon was added instead of vinegar; if you didn’t use lemons, you added vinegar. And it was actually very good. I never prepared this dish. This was the vorspeiss. If you had this dish, you didn’t eat fish anymore. If you had fish, you didn’t eat this dish. And then you had soup, meat – it was a must on Friday evening. Boiled meat, simple, there was no side-dish, we ate it with bread. And there was desert after the meal. And we had the same for lunch on Saturday, soup and meat also, with noodles added to the soup.

But everything was prepared on Friday. It’s not like you were allowed to do this on Saturday. Do you know what we used to heat the food? There were some oil lamps, and we placed the food on that and warmed it up. But someone had to come to light the lamp. But I had an aun in Galati, who later moved to Bucharest, and this is how she did it – you see, this religiousness –: the previous evening [before Sabbath began] she turned a chair upside down, placed the lamp on the chair, lit it in such a way as to burn with a small flame, placed the food there, covered it with towels, with this and that, and that’s how she kept the food warm for lunch the following day. It was rather dangerous. And she had natural gas in Bucharest, she left the cooking stove burning, but she only placed the food there on Saturday.

I will tell you the holidays in chronological order. The first holiday, which is usually celebrated in January-February, is Rosh Hashanah Lailanot – New Year for the Trees –, which occurs during Hamiş Aşar Bişvat, on the 15th day of the month of Şvat. [Editor’s note: The holiday of Tu B'Shevat marks the new year or the birthday of the trees in Israel. Tu B'Shevat translates as the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shevat.] It isn’t such a great holiday, it’s not as if you aren’t allowed to work, or anything like that. You eat exotic fruit, you recite certain prayers. But not all the Jews celebrated it. They celebrate it in Israel. We observed this holiday as well. It was a more festive meal, we ate regular food, but after the meal we ate oranges, figs, dates, raisins. You could buy all sorts of exotic fruit prior to World War II, even in Sulita, and especially in Botosani. But we observed this holiday when we lived in Botosani as well. After 1972, a kind of relaxation occurred in Romania, there were many products available to buy. I remember there was a store here, in Botosani, opposite the monument [Ed. note: The monument “Major Ignat’s machine gun company mounting an offensive,” erected by the Botosani-born architect Horia Miclescu and inaugurated in 1929.], where they had barrels of olives, shelves filled with chocolate, oranges, figs, raisins, fine khalva. But afterwards these products started missing again. And in those years when you couldn’t buy exotic fruit, you ate apples, pears, you waited at queues and bought grapes. This wasn’t the case in Sulita, there was plenty of everything.

Purim is celebrated on the 14 of Adar. Megillat Ester is read on the eve of Purim, the Story of Ester. They read this at the synagogue, not at home. And then, still on the eve of Purim, father performed the table ceremonies, he read the prayers specific for Purim. You prepare a festive table laden with all this world’s goodies, if you have the money to buy them. Housewives vied with one another with their cooking, who cooked better food. Everyone cooks whatever they want, but sweets are a must. They baked cream cakes, cookies, and those triangular cookies in particular – which resembled Haman’s hat – which were called hamantashen. I never bragged, for I never took care of that – I devoted myself to my profession. And parents sent children with sweets to relatives, friends, and each friend sent something in return. [Ed. note: Mrs. Segal is referring to shelakhmones here, sweets given to friends as gifts.] You could have friends over on Purim, relatives. Or we called on someone, we visited my mother’s sister, my husband’s brother. It wasn’t obligatory for us to celebrate it at our place, we called on one another on Purim. It was beautiful…

I only wore a mask as a child, in Sulita. And my mother gave me sweets to take to her friends. I wore my mother’s skirt, my mother’s jacket, her high heel shoes, on which I was really breaking my legs, and I wore a veil to cover my face, so that I wasn’t recognized, and I couldn’t see where I was going. But they recognized me immediately. I didn’t wear a face mask. Some wore masks as well, and they went from house to house. Those who wore masks also called on other people’s houses on the eve of the holiday, the second and the third day after the holiday. There were gypsies living in Sulita. And gypsies play the violin. And they went from house to house with a violin, an accordion, a cembalo, and they played Jewish songs for us, typical Jewish songs, and they were given money, so that they turned an honest penny. And the lights were on everywhere, it was so beautiful… Until 1941 – a fatidic year. Everything went to pieces in Botosani. We had no heart for all that in Botosani. We were even afraid. We still observed tradition, I can’t say that we didn’t. But people didn’t visit one another like they used to. We were in dire straits. These customs have disappeared.

After that, in March-April – on Nisan 15 –, we celebrate Passover. Passover is celebrated to mark the fact that Jews left Egypt and escaped slavery. We celebrate it in Galut, it lasts 8 days in the Diaspora, and 7 days in Israel. First and foremost, the day before the holiday, on the eve of the holiday, you must search all corners, all drawers in the house, so that no bread or anything that leavens is left in the house. For you aren’t allowed to eat anything that leavens throughout Passover. You weren’t even allowed to eat cocoa – we instated an exception with regard to cocoa. [Editor’s note: There are some additional food (besides chametz that refers to bread, grains and any other leavened products) that are traditionally not consumed in Pesah (Passover). The prohibition of consuming cacao derives from the suspicion of hametz that could have been mixed with the cacao during its grinding. Nowadays there is cacao (or coffee) on the market that is specifically marked "kosher for Passover".] And you wrap all the bread you can find in a piece of cloth and place it in a wooden spoon, and you burn it, spoon and all. The man does that, the head of the family. And if there is pasta or wheat flour in the house, you must make a list of them, and take it to the rabbi to show him what you have in the house. The rabbi probably recited a prayer or something like that, to the effect that we should be allowed to use it afterwards. You placed all these in a cupboard. For you didn’t have to take it out of the house if you gave the list to the rabbi. [Editor’s note: In many Jewish communities, the rabbi signs a contract with each of his congregants, assigning him as an agent to sell their chametz. One who keeps the sold chametz in his or her household must seal it away so that it will not be visible during the holiday. ]

Mother had separate dishes for Passover, which were stored in the attic. You weren’t allowed to mix them [the Pesach dishes and everyday dishes]. And another thing. We had no tap water in Sulita, and there were some people, poor souls, who carried water by cart in wooden pails. And when they brought water on Passover, we had a special, very large barrel, which we covered with a cloth, and the water was poured in the barrel through the cloth. And they didn’t bring water only on Pesach. They brought it all year long. But on Pesach this cloth was placed on top of the barrel, so that the water was more kosher, more “peisaldich” [pesachdich], in the spirit of Pesach. Who knows, it could be that that wooden pail wasn’t as it should be, wasn’t kosher.

Before World War II, matzah was prepared here, in Botosani. Nowadays we receive it from Israel. And when you prepare the meal for the Seder evening, there is a “cara” with 3 pockets, inside which you place 3 pieces of matzah. The cara is a sort of a small cloth sack, of maybe 50 by 50 cm, nicely woven – you write in Ivrit the word Pesach on it very beautifully, you make a Zion [magen David]. We didn’t embroider it, perhaps some people embroidered it, but I believe ours was done by my mother, or perhaps by my grandmother. It was made from white cloth on top, with yellow satin crepe, and the red writing. But those who were very religious didn’t put regular matzah, the kind we bought, inside the cara. They baked their own matzah in their oven, so that it was baked more religiously. This more kosher matzah was called shmura [shmura matzah]. Rabbis baked it. But in the latter years, there was no shmura anymore.

Then you place a piece of meat on a large plate, a piece of liver, a leaf of parsley, an egg, a piece of potato, horse radish. [Editor’s note: A roasted shank bone is put on the Passover Seder plate symbolizing the Pesah sacrifice. This bone could have been substituted by any other type of meat, e.g. by liver.] And a plate of hrotiot – hroisas [charoset] – is placed on the table for the table companions; the charoset is made from apples and walnuts and wine. Another very large, a little deeper plate is placed on the table as well, filled with boiled potatoes, boiled eggs and salted water. If the table is large enough, several of these plates are placed on the table. Each person at the table must have their own glass. And the glasses are filled with wine. There are 4 stages when you drink of this wine, and you recite a prayer. It is called “Arba’a kosot” – meaning four glasses. A prayer is recited in the beginning, and everyone drinks a sip. Then you take a piece of matzah from the first pocket of the cara, and the person seated at the head of the table recites a prayer: “Baruch ata Adoshem…” In fact, if you don’t perform an actual prayer, you aren’t allowed to say “Adonai” – “Baruch ata Adonai…” –, you must say “Adoshem,” so that you don’t take the name of the Lord in vain. [Editor’s note: The title "Adoyshem" is a substitution for "Adonay" used when someone utters the name of God aside from the proper religious context. Mrs. Segal only recalled the text of the benediction, thus did not intend to utter God's name. (It is very common to say "Adoyshem" during Torah study or when someone recites only half of a biblical verse.) It is a biblical prohibition to pronounce God's name in vain.] And everyone is given a small piece of matzah. And everyone dips the matzah in the charoset and eats. Then horse radish is taken from the large plate, it is placed between two pieces of matzah, and the one who performs the table ceremony gives each table companion a small piece of it. Then we ate boiled potatoes and boiled eggs from the large plate filled with salted water. Everyone ate as much as they wanted. I like eggs a lot, and I always took a whole egg and a whole potato. Then something is read: “Avadim ainu, bataum bamitzraim…” “Slaves have we been in the land of Mitzraim…” Mitzraim is Ivrit for Egypt. [Editor’s note: “The correct form is this: Avadim hayinu le-pharoh b’mitzraim”, “We were slaves to Pharaoh pharaoh in Egypt.”] And that prayer is read. Afterwards, a child has to recite the mah nishtanah. The four questions. It was my brother who recited it, he was the youngest. I recited it myself, even if I was older, as I liked to do it. Both of us could recite it together, for there was no problem with that. Mah nishtanah goes as follows: “Why do we eat tonight both sweet and bitter food?” “Why every evening we eat sitting or reclining…?” [Editor’s note: These are the asked questions: "Why is it that on all other nights during the year we eat either bread or matzoh, but on this night we eat only matzoh?" "Why is it that on all other nights we eat all kinds of herbs, but on this night we eat only bitter herbs?" "Why is it that on all other nights we do not dip our herbs even once, but on this night we dip them twice?" and "Why is it that on all other nights we eat either sitting or reclining, but on this night we eat in a reclining position?"] My father sat on a cushion when we celebrated Seder at home, and when a child recited the mah nishtanah, he used to recline, which is to say he tormented himself, so that he wasn’t seated comfortably. A prayer is recited afterwards, “Baruch ata Adoshem, elocheinu meleh haolam, bore pri hagafen.”, and everyone drinks the second glass. [Editor’s note: "Barukh ata Adonay eloheynu melekh haolam bore pri hagafen." “Praised are You O Lord our God king of the universe, Creator of the fruit of the vine.”] Not all at once, you still drink it by taking small sips.

After that a prayer is read, on and on – a part of the Haggadah is read – until “Gua litruel” is uttered, meaning “Gael Israel, ” meaning the redemption of the people of Israel. And then you are allowed to eat. [Editor’s note: The last benediction before the Passover Seder meal starts with the following words: "Barukh ata Adonay eloheynu melekh haolam, asher gealanu vegaal et avoteynu mimitzrayim, vehigianu lalayla haze eekhol bo matza umaror.”Blessed are Thou, Adonai our Lord, King of the universe, who redeemed our ancestors from Egypt, and brought us to this night to eat matzah and maror.”] And the characteristic of Passover food. First you eat eggs with potatoes – it isn’t a salad, the egg is mashed with potatoes, onion – with matzah, of course. Then they serve minced meat balls borsch. And this borsch is prepared specially – you aren’t allowed to prepare it from husk, God forbid. Husk comes from wheat. And you place beat in warm water and it goes sour. But I never prepared it myself. Nor did my mother, only my grandmother. After that we ate soup with khremzlakh, made from eggs with matzah flour. After the soup, we ate meat with latkes – baked from matzah flour –, and with keyzl – prepared in the oven, also from matzah flour and eggs – and horse radish. Then we ate stewed fruit made from black plums, and we served cream cake. But you weren’t allowed to prepare the cream cake using butter. My mother baked cream cake using scalded walnuts, and she prepared a cream made from butter – but this was after my grandmother died. As long as my grandmother was alive, we didn’t use butter for the cream cake, for it was made from milk, and you aren’t allowed to have milk after meat.

At the third koys, at the third glass, when the bracha is recited, meaning the prayer, they say “Svoh, amoh…” Which is to say the door is opened, for the Messiah to come. [Ed. note: In fact, they waited for the return of Prophet Elijah to drink a glass of wine with those who lived in the house. The front door of the house is opened after drinking of the third cup of wine. At this point Psalms 79:6-7 is recited in both Ashkenazi and Sephardi traditions: "Shfokh hamatkha el hagoyim asher lo yedaukha veal mamlakhot asher beshimkha lo karau, ki akhal et Yaakov veet navehu heshammu."] There is a glass of wine set aside for him, so that he should come and drink. I believed it, as a child. For my father went to the door, opened it, and I believed he would enter. But the Messiah never came. And at the fourth koys the afikoman was stolen, the third matzah of the cara. You eat the first one with hrosiot, the second one with horse radish, and the third is stolen. It was my brother or I who stole it in our home, and we asked our father money in return for it. For he couldn’t find it. And then mother pointed to us the place where to look in order for us to find it. Children’s games.

After the meal is over, the “Chad Gadya” is recited. [Chad Gadya, One Little Goat], which I know by heart as it is very nice, but it is like a tale. You must sing it, for it is written using musical notes in the Haggadah. My father sang it in our family. But people don’t sing it nowadays. I drew attention to this fact here at the Canteen. We have a choir, why should they not sing it? But still, I managed to entice them to do something, and they sang it last year: “Chi lo nue, Chi lo iue.” [Editor’s note: “Ki lo nae, ki lo yae.” “For to Him is it fitting, for to Him is it suitable.”] And at the end it closes with “Ehat mi odea.” – [Echad Mi Yodea, "Who Knows One?"] It was my father, meaning the one seated at the head of the table, who had to sing that.

But we always celebrated Seder in the family. We celebrated it at our house, and father was the one in charge of everything. And when my grandfather was alive, I think it was my grandfather who performed the ceremony – I was too little. There were very many people. We had less money, but it was done as it should be done, with all ceremony. Those who took part in it were our parents, we, the children, my mother’s sisters, both of my grandmothers – may God forgive them. But after I got married, my husband came as well, and my husband’s brothers with their family. And then it was like a beautiful holiday, as Ihil, my husdband’s brother, used to bring his violin along. And he played the notes in the Haggadah. And his son, Tucu, played the accordion. And it was very nice. And after the Seder was over, he played waltzes, tangos, we left the world of religion behind. Or he played Ciprian Porumbescu’s Ballad. [Ed. note: Ciprian Porumbescu (1853-1883): Romanian composer.] My husband liked it very much, and his brother played it. And we invited the neighbors as well. But this was after the Seder. We didn’t invite the neighbors on the Seder evening. And we celebrated the Seder for 2 successive evenings. But in Botosani we only have one single evening, at the canteen of the Community. You need money. And there aren’t any to be had.

During the last month of the Jewish year, called Elul, men go to the synagogue every morning, and they blow the shofar. That is the New Year calling. You call the New Year, and you shout, and you pray. Men do this, women never did it.

On New Year’s Eve, on Rosh Hashanah, we ate fish. We always ate fish as vorspeiss. We liked carp very much. There is a pond in Sulita, the pond of Dracsani, where they grew great fish. And the peasants brought us fish – not only to my parents, but to all Jews. And people ate fish. The Jewish tradition is to boil it, and especially the heads. I did that myself. First you boil a whole onion, until it is entirely soft. And it depends on how much fish you have, you boil so many onions. And after the onion is completely soft and after it gets cold enough, you strain it – by rubbing it. And almost all the onion is strained, if it is well boiled and soft. And after that you place this soup on the fire, you add a few peeled, washed potatoes, and you add the fish. The fish can be whole or sliced, depending on how you like it. You add a little sugar, pepper, salt, and after you stop boiling it and let it cool, the sauce becomes as thick as jelly, you can cut it with a knife. And this was done using the heads, mostly, for the heads are better for making that sauce turn to jelly.

And then, when I got married, I wanted to show I knew a thing or two – my husband wasn’t pretentious, on the contrary, he wouldn’t even let me do chores –, I prepared fish. But I also prepared fried fish. But I fried it using wheat flour, not corn flour. It is softer if you use wheat flour. It is very good if you use corn flour as well, but corn flour makes the fish harder. My aunt Rica taught me this. She is a perfect housewife. My mother was, too, but my aunt surpassed her when she baked sweets and anything else. And she told me: “If you want the fish to taste good, use wheat flour. For it makes it softer.” I slice the fish, I disembowel it, first I dip it into wheat flour, you need to beat 2-3 eggs separately, as many as you need, you dip it there – and it pays to let it there for longer, a quarter of an hour –, and then you dip it into wheat flour once more, after which you fry it. To be honest, I like fried fish better.

After the New Year, before the Great Day, which is called Yom Kippur – the Day of forgiving –, people go to a course of water. [Ed. note: On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, after the prayer after the meal, religious Jews went to a spring or a course of running water, where they shook their pockets clean – this procedure is called taslich]. In Sulita, we went to the lake after the meal, to the Dracsani lake. But I never did this here in Botosani. You go there, and you turn your pockets inside out, and you shake yourself free of all sins. Also, at the synagogue, you pound yourself with your fist on the wall, and say: “Al het hudusi” – “hatati” in this modern language, but I knew the “hudusi” variant, and you ask God to forgive you for the mistakes you committed. [Editor’s note: This prayer is part of the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) service. Confession (viddui) is a step in the process of atonement during which a Jew admits to committing a sin before God. A form of confession has been added to the daily prayer. The elongated confession is said only in Yom Kippur. The formula "Al het shehatannu" 'on the sins we commited' is repeated and competed many times.]

On the second day after the New Year, which is to say a day before Yom Kippur, you take a fowl – a rooster in the case of men, a hen in the case of women, and in the case of children it depends, either a rooster or a hen –, you spin it above your head, and you say: “Zot – it is zot in Ivrit, but it is zois in Hebrew – capurusi, zot halifusi...” I know the whole prayer. “This is the human being that dies instead of me, passes away instead of me.” For God writes your name in the book on New Year’s Eve, and on Yom Kippur, on the 10th day he announces the verdict, whether or not you will live. You spin while holding this hen… The Jewish name for it is kapores, but it is called kaparot in Ivrit. [Editor’s. note: The kappara ('atonement') is a Jewish folk custom during the days prior to Yom Kippur to transfer ones sins to a hen (women) or a cock (men). The woman recites the text in feminine gender: "Zot halifati, zot tmurati, zot kapparati. Zot hatarnegolet telekh lemita, vaani elekh veekkanes lehayyim tovim arukhim uleshalom." 'This is my substitute. This is my commutation. This hen goes forth to death, but may I be gathered and enter into a long and happy life, and into peace.'] I never liked it. I wasn’t afraid, but I felt ill at ease. The whole family did this, turn by turn – we, the children, as well. They used to buy a chicken for me and a small rooster for my brother – they bought young chicken for the children. And all these were slaughtered at the hakham, and were eaten at the family table. We observed this tradition in Botosani as well, but ever since there is no hakham, you couldn’t do this anymore. We gave them to charity after that. For giving a poor man some money is the same thing. Not to the effect that – God forbid –, the poor man should die instead of you, but you give something to charity.

When autumn holidays approached, we sacrificed many fowls so that we had plenty of food. And mother brought along to the synagogue liver, gizzard, those small yellow eggs that can be found inside the hen – larger, smaller eggs, only yolks. Oh my, how good they are! She boiled all of them in a soup, together with the poultry. But she took them out of the soup, she placed them in clean handkerchiefs and we, the children, went to the synagogue especially for that purpose, so that she gave us this to eat. Not only me, but the children of other parents as well. They tasted extremely good. And as soon as they gave us the food, we went to play – we were little. The parents stayed there for as long as the prayer lasted. 2 hours, 3 hours. The morning prayer could have lasted even for 4 hours. On holidays we also went there in the afternoon. But they didn’t give us food in the afternoon anymore, we ate at home. This happened on New Year’s Eve as well, and on Yom Kippur, when people fast. We, the children, didn’t fast on Yom Kippur. They didn’t even recommend that children should fast. I believe I started fasting ever since I became more aware of myself, when I was 7-8. And I’ve observed the fasts every year since then.

Sukkot comes after Yom Kippur. We built a sukkah on Sukkot in Sulita. The sukkah was built in the courtyard, everything – the roof as well – was made from reed, it was adorned with rugs and furnished with tables, chairs. It had 3 sides and another one, the one through which you entered, was open. You placed inside the sukkah the nicest things you had in the house. You placed on the walls and ceiling the nicest rugs you had. And you adorned it with all the fruit you had and could buy: with walnuts, apples, pears, grapes. That symbolizes the harvest. You hung fruit on the ceiling and walls. It was very beautiful. The Jews who are very religious sleep there, but my parents didn’t. Nor did my grandmother. You ate for 8 days inside the sukkah, as long as the holiday lasted, even if it rained, it was built with that in mind as well. We served all three meals inside the sukkah. Both breakfast, and lunch, and dinner. The food wasn’t special on this occasion. But we recited a prayer at every meal: the prayer for the bread, for the wine, for the food. There is also a separate ritual, involving the esrig [etrog in Hebrew]. The esrig is an exotic fruit, like a lemon – the exact colour of a lemon, even the size of a lemon –, and it has a leaf growing upwards. And it had to be pointed, for you couldn’t use it if it weren’t pointed. They sent us esrig fruit from Israel [Palestine] before World War II as well. You hold the esrig in your hand, and you recite a prayer, you bless the harvest. There were also some leaves beside it, which looked like corn stalks, which are part of the esrig. When this fruit grows, it has its own leaves, and they look like corn stalks, and you had to hold these leaves in your hand together with the fruit. Throughout the Sukkot, father recited the esrig prayer every day before the meals. This was traditional in Sulita. In Botosani, God spared us the joy of having a sukkah. One thing less to worry about.

Simchat Torah comes after Sukkot. It means the joy of the Torah, which means that you celebrate the Torah. It is a very beautiful holiday. Each synagogue had a member who was the most well-seen of all, the richest, and in Sulita, my father was the front-ranking one, the most reliable member – it was called gaba [gabe, gabbai]. And there were 2 synagogues in Sulita – they were competing with each other. And I always remember this: the members of the synagogue and children came to our door with little Zion flags – with magen David –, and an apple stuck on top of the flag, and with lit candles; they sang songs that are sung on Simchat Torah, and they invited the front-ranking member of the community to the synagogue. And then they went to the synagogue, they recited the prayer that needs to be recited every evening, but especially on that occasion they take out the Holy Scrolls, and they give the believers – the men – turn by turn a Holy Scroll, which is to say the Torah, and they walk – the rabbis wearing sideburns and beards dance – around the altar [Mrs. Segal is referring here to the bimah] and they sing. And when I was a child I used to walk around it myself next to my father, and I used to sing, as well. Father was holding the Torah, and I held father by the coat, by the hand. Oh my, it was such a joy…

Chanukkah is nice. Chanukkah is also called the holiday of lights, on account of the fact that people light candles. The Chanukkah candlestick has 8 branches plus an additional one which is the helper, the shammash, which you use in order to light the candles. And you lit one candle on the irst day, 2 on the second day, 3 candles on the third day, and you lit one extra candle on each successive evening. You lit them by the window. My father lit them. Then it was my husband who lit them. We had a large, beautiful one, but we gave it as a present to Mihai Pascal and Lucica, whom we visited in Petach Tiqwa. And people sang beautiful songs. “Ane rotala lu, alalu, / Ane rotala lu, alalu / sianu madlichim…” – “These candles that we light, may they remind us of the miracle…” –, this is the song I sang along with father, I liked it very much. [Editor’s note: This text of the song is the following: "Haneirot hallalu anahnu madlikin al hanissim veal haniflaot al hateshuot veal hamilhamot sheasita laavoteinu bayamim hahem, ubazman hazeh al yedei kohanekha hakedoshim. (...)" 'We light these lights for the miracles and the wonders, for the redemption and the battles that you made for our forefathers, in those days at this season, through your holy priests. (...)] Each evening during the 8 days, we sat down at the table to eat. People baked potato dumplings and red borscht, this was the traditional food. They also served meat and cream cake, that’s a different matter, but this was symbolic. The red borscht was prepared from beat and borscht made from husks, which we bought. It is called barrel borscht. You slice the beat, boil it, added a lot of vegetables, parsley, dill, carrots, you name it. And then you took all of them out, and you scalded it with this borscht, which has a greenish color. I never prepared it myself. My mother prepared it for me, then someone else prepared it for me. They still serve it to us every year at the Community. But only on one evening, that is all. They see to it that they serve it on a Sunday, so that those who have to work be able to come.

As children, we played with a spinning top. They were made from wood, metal. 4 letters are embossed on it, whose meaning is: “A great miracle was performed there.” N – Nas –, miracle. G – gadol –, great. Hei – haia –, meaning was performed. And sin – sam –, there. [Ed. note: "Nes Gadol Hayah Sham", referring to the miracle of the oil.] They gave me Chanukkah gelt when I was a child. They didn’t give me money, my parents gave me candy or they bought me shoes. Just as on Christmas or on St. Nicholas. It is a very beautiful custom.

I went to the cheder in Sulita, since I was 3 and a half, 4 years old, until I was 7, until I started going to school. I went there with other small boys, around 2 hours a day. But there weren’t many girls there. My grandmother, my father’s mother, was a very religious person, and she spied on me to see that I attended the cheder. And I actually liked it. I had a Lehrer – Lehrer means teacher, his name was Motas. And he used to say: “Odapam, odapam!”, meaning “Once more, once more!” [Editor’s note: "Od pam" means 'again' in Hebrew.] He taught Yiddish, not Ivrit. That’s why I can write and speak Yiddish. The letters are the same as in the Hebrew alphabet. But the words are different, and you write differently. I learned Yiddish only at the cheder, and afterwards I wrote and read Yiddish by myself, and I didn’t forget it. There was a bookstore in Botosani, where they sold books written both in Yiddish, and in Ivrit, and in Romanian as well. You could buy them, and I had at home books written in Yiddish, in Ivrit. But I kind of destroyed them under communism, I was afraid. I still have a few dictionaries and a few books in Ivrit, but that’s nothing compared to what I had.

Until I was 13, my childhood was a happy one. After that… it was awful. We had been rich until 1941, when the legionnaire regime 6 came to power and they kicked us out of our home and we left with the clothes on our back 1. And we began to experience dire poverty. Hadn’t the legionnaires come to power, we would have had such a good life in Sulita. They destroyed us back then.

There were legionnaires everywhere 2, they were in Sulita as well. There was a worker at a mill in Sulita, it was a Blumer mill – and they were rich –, and he carried wheat sacks at the mill. And when the legionnaires came to power, he became a leading legionnaire, and he came and knocked on our window shutters – well, someone put him up to this –: “Jews belong in Palestine!” But we didn’t want to leave. And then they kicked us out. My uncles who were living in Frumusica left, they came to Botosani as they feared the legionnaires. I couldn’t say when exactly, but still I believe they came to Botosani a year, a year and a half before we did, when the legionnaires came to power. But they moved there because they were afraid, for the legionnaires were in power by then, and they were knocking on windows, doors, they were threatening us. And they didn’t wait to be thrown out of their home. We did, and we were wrong to do so.

We kept our window shutters closed, we were afraid of the legionnaires. And one day that man who used to carry sacks at the mill came, he had become a great legionnaire, and was one of their front-ranking members, and he pounded on the window shutters: “All Jews must prepare for they have to leave.” At first, they didn’t tell us where we had to go. At first, men were supposed to go somewhere, and women and children somewhere else. But there was this woman, Filica, she worked as a telephone operator at the post office in Sulita, a woman of extraordinary nobility, whom my parents had befriended. My parents were very good friends with the mayor, the county chief, the notary, the scool principals… And there was nothing they could do, poor souls. But this woman, Filica, came and told us: “You know, if they find out, they will shoot me on the spot.” And I remember, she took my father in the back room – we didn’t know what was happening, we were also scared –, and she told him that a telephone call came through from Botosani, that they didn’t have train cars to send the men and women separately, and so we all had to leave to Botosani together for the time being. Well, we were happy to hear that.

And in June 1941, when we came to Botosani, a drizzle was falling – it was very fine, with no lightning’s or thunders –, and we sluggishly came to Botosani in a cart pulled by oxen – a distance of 32 km [35 km]. We were supposed to look for a peasant to rent a cart from him. We brought along as many things as we could carry. I couldn’t tell you exactly what… But I do remember that we certainly brought along a quilt, a pillow, the clothes that we were wearing, for we couldn’t take more, there were 6 of us. I had another sister and a brother, and my father’s grandmother lived with us. And so my parents plus my grandmother were 3 persons, and with us, 3 children, we were 6, all in all. Well, how many things could we take with us? For the entire merchandise, things, furniture, everything was left behind. And then the legionnaires burned it. They burned everything, houses, things. And I wanted to claim it back nowadays, based on law 112 [Ed. note: law no. 112/1995 for regulating the legal situation of some buildings destined for housing, who were entered in the property of the state.], but the lawyer – I’m surprised by it, he was a good lawyer –, who drew the sale-purchase deed of the house to my parents, didn’t record the surface area. He wrote: it has a common border with such, it has a common border with such, it has a common border with such. As they used to record these things formerly. And they didn’t record my claim. And I lost some money. If it were only for the money…

And you imagine, a fine rain was falling, and we used whatever we could take along in order to cover ourselves. We traveled in a group of carts moving together and accompanied by gendarmes. And they left us in the cattle market, where there was a cattle sale the following day. And the following day we were free to go wherever we wanted, for it was a cattle market, and people were coming there to sell cattle. My mother had a sister in Botosani, who was married and lived in Frumusica, and they had come to Botosani for fear of the legionnaires. They rented a house with 2 rooms, and we went there as well. They were 5, including the grandmother from my mother’s side – for the grandfather had died, too. And we were 6. And we lived like that in 2 rooms until we found something to rent. We found a room and a hallway in the same courtyard – which we turned into a kitchen –, and we moved out of there. And, I remember, they paid the rent for us. My uncle had sheep. I believe he had them registered under the name of a Romanian peasant. I’m sure of it, but I can’t say, for I don’t know for sure. I was around 13-14, and I didn’t meddle in their affairs. And they had money, and they helped us. There were very many things…

After they evacuated us, we were very destitute. We became poor people. I couldn’t say how we managed to get by. At a certain point we lived in a house located near the street, and they allowed us to open a small small ware shop. But I don’t know if it was enough for them to make ends meet. I remember that once, as a child, I told them I wanted to eat two eggs, and they told me they couldn’t give me more than one egg, for they had to give some to the other children as well. Do you know how sad it was? I liked eggs, I still do to this day, mainly fried. And I said: “I want two eggs.” And I started to cry. And mother, who was more severe, may God forgive her, would tell me: “I have 3 children, I must give an egg to each of them.” I wanted to show you how we lived. It was horrible. We almost considered begging in the street. But we were also helped by this sister of my mother’s, Branica. It was very difficult.

Not to mention the fact that starting with 1941, after we arrived in Botosani, we had to wear the yellow star 7, and during summer we weren’t allowed to go out after 8 o’clock in the evening. It’s not as if we went out during the day, either. You were afraid to do it. Yet you had to buy something, eat. But if you were caught in the street after 8 o’clock in the evening, they took you to the Police station. Children as well. We didn’t go out after 8 o’clock in the evening. We were afraid to do so.

The things that happened in Dorohoi… The things that happened in Iasi… A lawyer from Iasi, Avram Riezel, a very handsome man, who was a second degree cousin of my parents’, was boarded on the death train 8. He died in that train car, together with his wife, Sally. They had no children. He was born in Sulita, but he married in Iasi with a very beautiful woman, herself a lawyer, they were very well off, she was rich, and he was rich when he left Sulita. His parents owned sheep. And they also had land, I believe, but they didn’t till it themselves, they hired people to do that. And someone who survived the death train experience – a friend of this cousin of my parents, someone who moved to Bucharest afterwards, and we met him – he told us how, forgive me, they relieved themselves right there, on straw, they weren’t given any water, food, nothing at all. And when the train stopped in Targu Frumos, there was this lady, Garici, may God rest her soul, and she approached the train to give them water to drink. For the train car had small, barred windows. And they slapped her over her arm, and she had to leave, otherwise they would have shot her. There were gendarmes on guard duty. And there is Yad Vashem 9 in Israel – I was there –, and there is a road there, where they planted trees “Righteous among the nations.” And Mrs. Garici has her own tree planted there. She passed away. She has a daughter here, in Romania, I don’t know how old she is, who has cancer, I believe. And she was sent to Israel for treatment. Well, if they could save her… But still, her mother’s gesture was extraordinary.

In 1943 – I remember precisely, it was during autumn – my father was taken hostage by the legionnaires – but no longer remember whether it was with the help of the Police or of the army. And I thought they were going to shoot him, that they would ask him to do some things, and if you didn’t perform what they required of you, then they would shoot you. For you were in danger of being shot during the legionnaires’ regime. I remember this man, his name was Catana, he was a legionnaire. For I can see him before my eyes with his green shirt and leather belt. They had this uniform: green shirt and a slanting belt strapped to a girdle, and they wore a badge attached to the belt, but I couldn’t tell you what bas embossed on that badge.

Had they wanted money… But they didn’t want money. My aunt Rica, my mother’s sister, went to the house of one of the officers – I couldn’t tell you exactly who, but I believe he was from the Police –, whose daughter she had befriended, so that she could negotiate with him. Nothing could be done, the legionnaires were very mean. We were desperate, as father was there and they could have shot him at any time. But my father escaped with his life. He was held hostage for a few months, until April 1944. Until the Russians came. If the Russians hadn’t come, I believe he wouldn’t have survived, they would have shot him. But the day of April 7, 1944 came, when the city of Botosani was released. The city was bombarded on April 7, 1944, and the Russians came. If it weren’t for the Russians, we would have ended up in concentration camps. They held these hostages as a means of exchange. They didn’t take them out [they weren’t taken to perform forced labor]. They beat them with a belt, that’s what my father told us. They were held hostages in a synagogue, the synagogue that they still use to this day. There were several Jews there, around 20 of them. They were the richest ones. And afterwards there was a mess with a certain man, whose name was Calmanovici as well, and whom they arrested as well. And he claimed they took him because of my father, for he had the same name. Well, you think my father could have had any say in that matter? My father was taken away based on the lists they had when they came to our house. They brought along a list and the financial means were written on that list. Next to my father’s name was written “good.” And they took away all those who had good financial means. But it didn’t make any sense. We had nothing left at that time anymore, for we left everything behind in Sulita. But if they hadn’t burned what we had in Sulita themselves, they could have taken everything from there. I have the list, I took it from the Centre for the Study of History in Bucharest. As I am a beneficiary of the law 118 [Ed. note: Decree-law no. 118 passed on March 30, 1990 with regard to granting certain rights to the persons who were persecuted on political grounds by the dictatorship in force after March 6, 1945, as well as to those who were deported abroad or were taken prisoners (updated until April 19, 2002)]. The one regarding those who were relocated, deported.

When I came to Botosani, I believe more than 50% of the population of Botosani was Jewish. And what did Jews have? Stores. There was a man in Botosani, his name was Bogokovski, who had a large store, and then, in order to be able to keep the store open, he entered a partnership with a Christian, he recorded the shop as being owned by a Christian friend 10, but he was a nice man – I forget his name. And the store was recorded under the name of that man. That man wasn’t a nobody, either, financially, that is. And they caught them, they found out the former registered his shop under the name of the latter, and they arrested Bogokowski. Only the Jew. I remember this, for we were outraged back then. Life was very hard. But he escaped with his life as well when the Russians entered Botosani.

The Russians entered Botosani on April 7, 1944. Afterwards, it wasn’t long until August 23 came 11. And on April 7, when the Russians came, there was such a bombardment… The Germans bombarded the city, for they knew the Russians had entered the city. They bombarded the theatre building – it was rebuilt –, and I don’t know what other buildings they hit back then. We hid inside the cellars. Had they bombarded the house, we would have been dead.

After World War II, it was the Joint 12 who helped us. We were very poor. Later on, I had my own salary, and so did my father, but we couldn’t afford to buy neither furniture, nor any fancy clothes. The Joint founded a canteen in Botosani in 1945. And my father, poor soul, he had a superb handwriting, it was very beautiful, and very accurate, and at first he was hired at the canteen as administrator, then he was in charge of primary book-keeping, and I don’t know exactly what other position he had there. I believe this canteen was open until 1948. The Joint canteen was located near the co-operative that was founded in 1948. It wasn’t an agricultural or a craftsmen’s co-operative, it was a co-operative whose object of activity were countryside stores. And then they employed him at the co-operative in the billing department. For he wasn’t an accountant. And he had that job in the billing department until I don’t know when. The co-operative’s offices were located in the courtyard in front of the Community – the Jewish Community of Botosani. And they were missing a cashier at the Community. And they knew about my father, perhaps father visited the Community center, I couldn’t tell you that, and they employed him as a cashier. And he was required to write everything that needed to be written, records, stuff. For father’s handwriting was very beautiful and accurate, he wasn’t illiterate. And he worked at the Jewish Community until his death, in 1969.

I do my own praising: I was a very good pupil. As long as my parents lived in Sulita, I graduated 4 grades of primary school at the Jewish school. There was a Jewish school in Sulita, but we had to pass an exam at the end of each school year, which validated our graduating that year. There were 2 schools in Sulita, “Andreescu” and “Scurtu,” I passed my exams at “Scurtu.” It is as if I see before my eyes the building where the Jewish school was housed: you entered a long corridor along which there were 2 classrooms on either side, a teachers’ room, and I don’t know what else. The classes were mixed, made up of boys and girls. Goldenberg was my teacher from 1st grade until 4th grade, he taught all subject matters, only Ivrit did I study with a certain Zinger. I remember there were 2 other teachers, Nuta Schwartz – Nathan Schwartz – and a certain Balter, but they taught different classes. After I graduated 4 grades of primary school, I went to high school in Botosani. I graduated the 1st and 2nd year of high school at a high school for girls called “Carmen Silva.” And I rented a room from someone, for my parents could afford to pay for that. After 1941, I was no longer able to study at the Romanian school 1, and I skipped a year. All Jews were expelled from schools. After the Jewish High School was founded, I studied there. But I skipped a year, until this high school was founded. And then I sat for an exam to graduate the year – those of us who had skipped a year were allowed to graduate 2 years in a single one. And I studied for an entire summer. The Jewish High School was founded in 1942. Be that as it may, Antonescu 13 approved the founding of the Jewish High School. There was a rabbi in Bucharest, his name was Filderman, who had influence over him. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Filderman] Filderman spoke Romanian so well… we’d all be glad to speak it as well as he did. And he intervened around Antonescu for the foundation of a Jewish high school. And I entered the Jewish High School, and I graduated 3rd and 4th grade. But girls weren’t allowed to study at this high school. They enlisted us, but they kept separate rolls. And there was an inspection once – I will never forget this scene –, and the principal stormed inside the classroom: “All the girls must run out of here immediately, for there is an inspection!” Well, we ran and we returned afterwards. You can imagine the situation we were in. That’s how I studied.