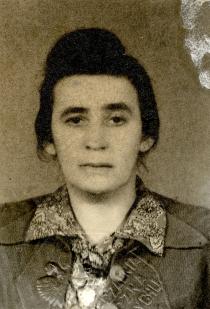

Rena Michalowska

Warsaw

Poland

Interviewer: Maria Koral

Date of interview: October 2005

Mrs. Rena Michalowska has a one-bedroom apartment in a post-war building in Warsaw. She lives alone. Most of her closest family lives abroad. Mrs. Michalowska is a keen participant in various intellectual and cultural events. We met five times. Each time I saw her, Mrs. Michalowska observed that going back into her past and describing the lives of her family and friends is very painful to her. I had a feeling that above all she wanted her memories to be recorded somewhere, not only in her memory. Mrs. Michalowska likes reserve and matter-of-factness, but her recollections are very vivid and filled with strong emotions. She insisted, several times, that she never tried to hide her origins. She signed our agreement with no reservations, which is not a rule in the Polish interviews. She was particularly troubled by the subject of anti-Semitism in post-war Poland. She was proud and moved to tell me that her granddaughter, who's lived in the US for some time now, has sent her an artwork demonstrating her remembrance of her Jewish roots.

Family background

Growing up

During the War

After the War

Glossary

I was born in 1929 in Tysmienica, near Stanislawow [today Iwano-Frankowsk, Ukraine, ca. 120 km south of Lwow]. I have no idea who my great- grandparents were, what their names were, where they were born and where they lived. I can't remember any conversations about the third generation back. My closest family are those I can remember, that is, my father's parents and his three sisters.

If my grandparents weren't born in Tysmienica, they must have been born somewhere in the neighborhood, in the small world of Galicia. 1 My grandmother was referred to as Toni, which must have been a diminutive from Taube. Her family name was, I think, Schrager, but I won't swear to that. I have no idea when she got married. My grandfather's name was Leon; that must have been Lejb, Fischbein. What he did earlier, I don't know, but as far as I can reach with my memory, he was always said to work in the horse trade. It probably amounted to going around to horse trade fairs. Everybody made fun of him for being completely inept; they said he usually loses money on his horse transactions - he never made any profit. To my mind, it was my grandmother who provided financial support to the family. I know from stories I heard that she started out by washing, starching and ironing all those things one used to attach to shirts: collars, fronts, cuffs. She was good at it. I remember her say, 'I got those sent even from Stanislawow, and Lwow.' When she gathered a little capital, she bought two cows and made dairy products from the milk. These were not educated people. They focused on surviving, living, and having their children survive.

My father, Jakub, was the oldest, born in 1902. His sisters, from the oldest to the youngest were: Chana, Hesia - I can't remember the Jewish name again - and Eta, Etel. I have no idea which years they were born in. I have a vague memory that there were also two brothers who died, as babies or children. This subject was avoided, not to cause my grandmother pain.

I don't know where and how my parents met. My grandparents on my mother's side were probably also from Tysmienica. I don't know what they did. My mother had a very interesting Jewish name, Judenfreund [literary 'Jewishfriend']. Her name was Mina. She was also born in 1902. My mother didn't remember her own mother well, because she died soon after my mother's birth. My mother had a sister, much older than herself and a brother whom I haven't met because he died young of consumption. I can't remember their names. Her father also died of consumption. But has ever anyone diagnosed them? It's like in this joke, 'When does a poor Jew eat chicken? When the Jew is sick or the chicken is sick.' How much of a doctor's diagnosis was there? He was sick and he died. My mother became an orphan at the age of 12. She went to elementary school in Tysmienica. When her father died, my mother lived with a distant aunt in Stanislawow, who - that was an embarrassing thing - used to be kept by various rich men. I don't know how long my mother lived there. She was supposed to be taken in as an orphan, out of pity, but she was basically a servant at her aunt's house. Was it there that she met my father, or in Tysmienica? I don't know anything about their wedding, but I assume some rituals were observed. My father adored his mother and he wouldn't want to disappoint her by simply signing marriage papers at the magistrate. They may have had a wedding with a Rabbi, most likely in 1927 or 1928.

The land around Tysmienica was flat, I can't remember any rises or hills. So was Lwow [now in the Ukraine] and Stanislawow, plains all around. Nothing stood out except for the little river, Wrona. There was a railroad, but the distance to it from the town square was so great that it made more sense to travel by carriage, only 10-12 kilometers to Stanislawow. I suppose Tysmienica was a typical little town with a town square and some streets going out of it. No street lights. There were pavements, but not everywhere. Not all streets had cobblestones, some were plain beaten dirt roads. Once a week there was a fair and then the traffic was immense! Carriages would come from the neighboring villages. I can still remember the sound of the wheels sheathed with metal, rather than rubber. The cobblestones were uneven, of course, so from early morning, particularly in the spring and summer, when the windows were open, one could hear the horses' hoofs and the metal wheels.

The population of Tysmienica was several thousand: Poles, Jews, Ukrainians. The street language was Polish-Yiddish, I think. Among the inhabitants of Tysmienica was a colony of Armenians; that was quite exotic. The group was big enough to have their own church. Maybe people came to that church from all the small towns and villages around Tysmienica? There were also two Orthodox churches - one in the town square the other basically outside of town - and a Roman Catholic church. Everything was close at hand. I remember one synagogue, also close by, and there was another, I think. It was a white building, but I can't tell whether it was wooden, painted white or covered with lime, or stone. I know there was a Jewish cemetery. I've never been there. I don't know whether it's a ritual or a custom that children are not taken to the cemetery. Luckily no one from my close family died, I didn't have a funeral to go to. As far as I remember women didn't go to the cemetery, only to the funeral home. I can't remember very orthodox Jews in Tysmienica: those that would wear long side curls and the like. They did wear those... I don't even know what they are called [tallit katan]. There was a Rabbi or two, three Rabbi. There were some Jewish store- owners. They owned general stores, with barrels of herring next to barrels of paraffin-oil. There were some furriers - tanners and sheepskin coat makers. I remember one Jew who was considered very rich, I think his name was Blum. He had a textile store. He or one of his sons also had a hardware store.

My parents lived on the street parallel to that side of the town square where my grandmother lived. A spitting distance, I'd say today. I can't remember the name of that street. The house where I lived with my parents was the only house in town which went above the ground floor, it had two floors. It was a brick house, with a gallery which run along one side. There was a one-story annex, perpendicular to it. At the end of the gallery there was a toilet - no water of course. There was a big courtyard with a garden divided into three sections. We lived on the second floor. It was a rented apartment which consisted of a large kitchen, a dining room and a room one entered from it. There was an unpainted wooden floor in the kitchen - I think a girl came once in a while, not very often, to scrub that floor. In the two rooms the floor was painted brown. I can remember a lampshade with beads - on top of an oil-lamp of course, there was no electricity.

What I do remember - and that must have been quite an accomplishment on the part of my parents, or my father's stubbornness to save enough - is a Telefunken radio we had. There was this big box on the desk, with a round speaker and under the desk there sat a huge battery on which the radio run. We had tile stoves in the rooms and the kitchen was heated by a coal stove. Obviously the house had no plumbing. A special water carrier brought water in barrels, pulled by a horse. I can still hear this man going round - I think he was a Jew - and calling: 'Waaater, waaater, who needs water...' He would unplug the barrel, which was stopped with a wooden peg, and poured water into buckets. He had a special plank for carrying those buckets on his shoulders and he'd bring them up the stairs. I don't know where he got the water from. Maybe straight from the river?... There was one kind of tub for the laundry and another one, resembling a bathtub - oblong in shape, tin, covered with zinc, with a wooden stop - for taking baths. When it wasn't used we put it behind some curtain. And so, we took a bath, once a week, I'm afraid. As in any typical small-town Jewish family, first in went I, then my father and my mother last, in the same water. Such was the hierarchy.

My mother didn't have a profession, she took care of the house. I believe my mother was a very pretty woman. She had large dark eyes, dark brown hair and - something I will never forget - a shapely nose. Since her own nose was thin, long but quite thin, she used to say to me, 'You know what? Why don't you squeeze your nose from time to time, maybe it will become thinner.' She was a shapely woman, with a pretty, oval face, as you can see on the pictures. Her problem were the large - really large - breasts. She dressed in modern clothes. She even wore a type of corset, laced up in the back. I remember that, because sometimes she she'd ask me for help: 'Would you pull a little here, please?' My mother called me Niunia. Apparently I named that myself. My original name is Regina. She spoke very good Polish: without an accent, without deforming it and with perfect grammar. Despite the fact she finished only 6 grades of elementary school, as she herself emphasized, she was a polyglot, as most of the people from Tysmienica were; she spoke good Yiddish, Ukrainian, Polish and relatively good German. My parents spoke to each other in Yiddish.

My father could write and read in Yiddish, so he must have gone to cheder as a child. He was circumcised and most likely he had bar mitzvah. I'm sure he also went to a Polish school. In addition to that, he studied at the teachers' seminar in Stanislawow. He was an extramural student, commuting to some classes and taking exams. I think it was a Polish school because it gave him teaching qualifications. What kind? I can't say. Maybe general? First he was getting ready for the Kibbutz, through an illegal relocation to Palestine 2. Then he came across the communist movement. He was a young man, very young, when he joined the KPP section 3 of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine 4. He had no stable employment, because - as I like to joke today - he was a professional communist and no one would give him a job at a public institution. In such closed communities everybody knows everything about everybody else. As far as I remember, my father did someone's accounting. He occasionally gave lessons, usually Polish to Jewish children. I even have a souvenir of that, a little scrap that was saved. When I was born or turned one, the Rabbi, who was very grateful that my father taught his son such good German (the boy even went on to study in Vienna), gave my father a silver knife, a fork and spoon [with RF initials].

My mom was so dominated by my father, that she maneuvered, somehow, between his views and what was left of her desire to stick to the tradition. She had candleholders and sometimes on Friday she lit the candles when my father wasn't there. When she heard him coming up the stairs she blew them out and put them away. She had a Pesach dish set and she even brought it out; I guess she had my father's permission for that. The food was Jewish, but not kosher.

I think that only Jews lived in our house. I don't know who was the owner. At the same floor, in an apartment smaller than ours, there lived two women, probably spinsters, who did some sewing. I remember hearing the noise of the sewing machine. They liked taking care of me and feeding me and my mother was angry at them that I don't want do eat at home, but eat at their place; and that I shouldn't be eating up the little that they have. So it came to that my mother secretly brought food to their house, so that I would think it's theirs and like it and eat it. A floor below, in an apartment like ours, there lived a man who was a doctor or a lawyer. That was a richer household than ours and I wasn't welcome there, I think, either because we weren't as rich or because my father was a communist. They were very middle class and cherished their status. Since they were Jewish, they couldn't have held my Jewishness against me.

My mother's sister lived with her family in Tysmienica. They had a tiny store. I don't remember her husband's first or last name. I only remember him as a shrunk, cowering little man. I remember nothing else - no facial features, only this cringing nervous figure. There were two children, a girl and a boy, I think. We didn't see them often. Was it because they were so poor, while my grandmother on my father's side was considered quite wealthy, with her own business and her own house?...

I used to spend a lot of time at my grandparents' - my father's parents - house. The house stood at the town square. It was a one-story brick house. There were two small rooms up front and I remember a cement floor. There was a kitchen and then, as far as I remember, the entrance to my grandparents' bedroom with the windows facing the courtyard shared by several other houses. There was another room, with the window facing the street, where my father's sisters lived. Further on, there was some kind of hallway, a vestibule or a pantry, also quite large. I also remember something like a barn, where the cows were kept, though that was before I was born. Then, occasionally, horses were kept there which my grandfather bought or sold, though none of these horses stayed for good.

I remember this barn so well, because at the age of 4, 5 or 6 I had terrible whooping cough. My grandmother immediately bought a goat. She milked that goat three times a day and I had to drink a glass of its milk, still warm from the udder. I was bribed with a piece of chocolate. Until today I can't stand the smell of goat-milk diary products; it makes me remember my childhood when I was made to drink goat's milk. I had one doctor, but there may have been more in Tysmienica. I know I had measles, chicken-pox, and maybe contagious hepatitis. There was a dentist in town, we used to go to his office. The doctor and the dentist were Jewish. I think you had to pay for the visits. Since nobody in the family worked at a public institution, I assume we all had to pay with our own money.

We were all supported by my grandmother. She was a woman of middle height. The most striking aspect of her appearance were, I think, the almost violet eyes next to black hair. She dressed in normal clothes, not what you would call the outfit of a Hasidic Jewish woman. She wore mostly long sleeves and mostly longish calico dresses. I remember her always wearing a clean apron. I usually saw her at work.

At some stage, before the times I can remember, she gave up on the cows, and milk was delivered by the peasants, Polish or Ukrainian, because Jews in Tysmienica, the town itself, rarely kept farm animals. Or maybe Jews from the neighboring villages brought the milk? I really don't remember. I think my grandmother didn't buy from that many sources, or she wouldn't be able to use all that milk. She probably depended on the same, reliable deliverers for half-product. There was a room where that milk was kept to turn sour. I remember those clay bowls and the wooden spoon you used to scoop up the cream from the top to put it in a separate dish. Then, the sour milk from several bowls was placed in a cooking pot. At the beginning my grandmother did that by herself. But as far back as my own memory goes, there were three women working: my grandmother, one of my father's sisters, and a Polish woman, Miss Rozia. I have to say Miss Rozia, for even if my grandmother called her Rozia, when I called her that, my grandmother would reproach me: 'She may be Rozia for me, but for you she is Miss Rozia.' I can still see those three women, how they place a big pot with the sour milk on the coal stove for the milk coagulate, how they take if off the stove and pour it out to strain it. I can see all that; more, I can remember how I couldn't resist trying the cheese. I loved cottage cheese, so sometimes even before it was shaped into crescents, I would dip my hand into it and get slapped and get yelled at, 'Keep your hands out of this!' The kitchen was very large, with an always scrubbed table and floor. In the hallway there was a bucket for the ashes, mostly wood, because coal wasn't used that often in the stove. They poured water over the ashes and left them standing for a few days to make lye, later used for washing the tables and floor in the kitchen. I remember how clean everything was in that kitchen and I remember, even today, the smell of the wet wooden planks of the floor, the smell of unseasoned, unpainted damp wood.

There was another room behind the kitchen with a press for squeezing out the liquid from the cheese. I can remember how I was getting in the way trying to help. There was also a churn for making butter; today they probably have such things only in museums. The butter had to be beaten in the churn, then rinsed, then placed in forms. Later my grandmother modernized and bought a hand centrifuge for extracting cream and a barrel, hanging on a metal bar, with handles on both sides. Two people stood on both sides, making the butter. I always observed the whole process with fascination. In the front of the house, there were two rooms: one in which there was the barrel and the centrifuge and one in which my grandmother sold her products and where the peasants brought the milk.

Both Jews and Poles bought those products from her. Once my grandmother took me to a very old Armenian woman. On the way she told me that the woman is a countess, and that I'm supposed to kiss her hand when we meet her. Once every week or two my grandmother went there to do the bills; the products were always picked up by the countess's servant and my grandmother added them to the bill. It wasn't far off, somewhere in the vicinity of the town square. The room was, I'd say today, rather gloomy and dark, very crowded with lots of furniture and knick knacks. This tiny little dried-up creature sat in a deep armchair. Since my grandmother told me to kiss her hand, I remember the many rings. And the fact she wore mittens [used in reference to fingerless gloves].

My grandmother took notes in a little book, but I don't think she wrote in Polish. My grandparents spoke exclusively Yiddish to each other. There were even days when my grandmother would say to me: 'Enough is enough! If you don't speak Yiddish to me, I won't understand you, I won't answer.' But she could speak both Ukrainian and Polish fluently. I don't know whether she made grammatical mistakes or not, but I can't remember her speaking a broken language. The clients were not all Jewish, anyway. My grandmother spoke Polish to Miss Rozia who lived with my grandparents. My grandparents took care not to work on Saturdays and on those days Miss Rozia did the necessary chores. I remember her as an older woman. She was either my grandmother's age or a little younger.

My grandmother kept a kosher house and when she came to visit us at our home, which was not kosher, she only drank tea from a glass. If there was sugar in cubes, she put a cube in her mouth, if there was none, she drank her tea without it. She didn't use a spoon, for while a glass doesn't make things unclean, the metal spoon does. She never ate anything at our place. I remember how the meat was koshered in her house. It was placed in a kind of wicker, sieve-like container, salted and kept like that, I don't remember for how long. Then it was rinsed and prepared, cooked. But where did they get the meat? I have no idea. There were a few butcher stores in Tysmienica, one of them run by a Pole and one by a Ukrainian. There was also a Jewish slaughterhouse. Once I insisted to go with my grandmother, so I remember the slaughterhouse very well. I remember it because afterwards I couldn't sleep for several nights and I'd wake up with a very unpleasant feeling, all because I insisted to go in and I saw how the butcher cuts the hens' throats and how he holds them afterward.

My grandmother made Jewish dishes. There was not much variety, but then Jewish cuisine is not particularly known for its variety, unlike the French- Italian cooking with its finesse and broad range of choices. She baked and cooked, but I never saw a cookbook and I don't remember any recipes. Among the dishes she made there was herring, mostly pickled, meat balls, chopped liver, of course, potato pancakes, beef roast and chicken stew. Veal was a delicacy that was quite rare, because it was very expensive. On Friday my grandmother baked challot.

All Friday evenings I can remember I spent at my grandparents. The evening begun when my grandfather came back from temple. He went alone, Grandmother went less often, she was much more busy. I remember how she put on a scarf to bless the candles. I can't remember if my grandfather wore a yarmulka when he came to the table or not. He usually wore a cap, but at home I saw him very often with a bare head. My grandmother prayed over the candles and my grandfather did that at the beginning of the dinner. After the candles were lit and the prayers were said, my grandfather broke the freshly baked challah and gave everyone a piece. There was a dish with salt on the table. I remember I was supposed to begin dinner with breaking a piece of challah and dipping it in salt. Such was the ritual. Then eating started and there were things one said, but no, I don't remember what they were. I'm not sure if there were always starters; almost always there was fish, either jellied or stuffed, I can't remember fried fish. Then there was broth with noodles made by my grandmother, which were yellow, made with egg yolks only, thinly cut. I can still see my grandmother making those noodles, I never saw that after the war, because where would I see it. An onion, slightly roasted on the stove, gave the broth a special golden tinge. There was boiled chicken and boiled beef. My father and grandfather liked very much what later would be called 'beef with a flower': meat with some fat around it. Another thing were potato latkes, similar to the potato pie they make in central Poland. Only my grandmother and my mother made them flat. It was a simple dish: in a flat baking pan, one placed pancakes made of grated potatoes mixed with eggs, flour, salt and onion and baked them. They were very tasty, both hot and cold. I can't remember my grandmother making chulent. I can vaguely remember something like that, which I didn't like, because it was quite fatty. But then, there was goose neck, stuffed with flour and lard, with cracklings, baked for a long time in the kind of potato mixture one used for the potato latkes.

I saw my grandfather mostly on Friday evenings and on Saturdays. On Saturday mornings he went to the temple again, this time with my grandmother. The temple was close by. Now everything seems to me as if it was a few steps away. One Saturday my grandmother woke me up very early and said, 'Niunia, tell me honestly, did you take Grandfather's moustache brush?' - she was right of course - 'Grandfather can't go to temple, because he can't brush his moustache.' My grandfather was tall, well-built, had reddish brown hair and no beard but an ample mustache. He had a special brush for the mustache, which looked like a regular big brush, only was smaller. And since I recently got this doll in a dark dress, I borrowed Grandpa's brush to comb her hair...

All of the seders were also held at my grandparent's house. But I remember them somewhat vaguely. For example, I can't remember my father asking the questions, and if he didn't, I don't know who did. I can't remember ever answering. I remember broth with dumplings which simply dissolved in your mouth. And matzah. Matzah was always fresh for Pesach, as there was a Jewish bakery in Tysmienica, near the town square. If there was matzah left from Pesach, my grandmother made 'matsebray,' pastry made from matzah crumbs. I know the recipe. Matsebray: dampen the matzah with water and mix with beaten egg. If you want it spicy, you can add salt and pepper, or you can make it sweet, with sugar or fruit preserves. Fry it on a pan. I remember the 'kuczki' celebrations [Sukkot] and all the booths built in the courtyard from tall corn stalks, for lots of corn grew in that area. A number of houses shared that courtyard, but I think each family had their own booth. There were tables made of wooden boards, and one sat down to eat at those tables. That's one of my memories. I also remember how my grandmother lit the candles [for Channukah], but I don't remember getting presents, maybe some pennies. But I remember Purim very well and the triangular cookies shaped like Napoleon's hat. I can remember their taste to this day. I don't know the recipe, only that it was shortcake made with honey. Those 'humentash' [Yiddish], or Hamman's pocket [ear] were filled with poppy seed mixed with raisins, sugar and honey. My grandmother made those, as the celebrations were held mostly at her house.

My mother was also a very good cook. She must have cooked the same things my grandmother did. She made everything based on memory and intuition. I remember her gorgeous strudel, pastry made without eggs, with flour, olive oil and water. It required a tremendous amount of work. You had to knead the dough long and well and then roll it out very thin. You then stretched it on a tablecloth until it was thin like paper. The pastry was filled with: cherry preserves, nuts, raisins, a little bit of apple went in as well, sugar and vanilla. The richness of this filling was unbelievable. After you sprinkled it with bread crumbs and laid it out on paper, you rolled up the pastry and put it in the oven. My mother's cooking was typically Jewish. I think she didn't cook pork, she was simply not accustomed to it.

I remember how my father used to make a show of taking me to the butcher's and buying a ham sandwich. At my grandmother's, he sat at the table without a covering for his head. His parents let him get way with that. But when he once lit a cigarette on a Saturday in front of my grandmother, there was a huge row and he was scolded like a bad little kid. They knew he wouldn't want them to draw me too much into this religious thing, so I think they didn't take me to the temple too often. After all, my father started his affair with communism even before I was born. Even if my grandparents were surely very simple people - apart from having taught themselves to read and write in Jewish, they had no education - they were full of dignity and understanding, especially for my father. I gather from their manner of behaving and from what I remember, that they tolerated what he did. And more: when my father wasn't working, I think my grandmother simply supported me and my mother. My father was formally the co-owner of his brother-in-law's (his oldest sister Chana's husband's) little store, but from what I understand that was merely the cover for the police, even if my father did show up over there once in a while.

The store was small, situated at the town square. It was not a grocery but a general goods store. There were basically a few pieces of everything there: from underwear to shoes. I can't remember any clothes, only some haberdashery, shoes, stockings, some underwear. The kind of shop you can find in a small town: three pairs of shoes and underwear elastic. I remember what that store looked like, because I liked to go there and watch, or play with buttons, for example. The store was long and narrow, with a counter to one side, some shelves behind the counter and some space for the clients by the entrance. It was mostly my uncle who worked there, my aunt helped occasionally.

My father's sister, Chana was a big woman. My father was about 1,76 meters and she was as tall as him. I remember a hefty woman, with pretty large breasts and quite wavy black hair. I remember her from the time when she was already married, so her hair was gathered, rather than loose; she must have worn it in a bun or something. Her husband's name was Icchak, I think, but I can't remember his last name. I am sure that, following my grandmother's example, they ate kosher, but they were only mildly religious. Their daughter, Bronia, was 2-3 years younger than I was; I can't remember the name of her little brother.

The middle sister, Hesia, stood out, because she wasn't that tall. I remember straight, shortly cropped hair, but nothing characteristic otherwise. She didn't get married. When it came to her, everybody gave up on that. She had her own room in the family home, which, I think, she shared with the youngest sister, Eta. Hesia stayed there frequently, but she worked in Stanislawow, at a Jewish dentist's office, as, you would say today, a dentist technician. She must have had some professional education, which she must have gotten in Stanislawow, for it wouldn't have been in Tysmienica. Once she even took me to the office. I was very impressed. She warmed something up over a gas burner. She was making dentures and showed me her work. She had great manual skills. When she was not is Stanislawow making various crowns and such, she was at home embroidering, crocheting or knitting. I used to have a white organdie dress with an embroidered front which she made for me. And even some shirts. I'm not sure if she wasn't the one who knitted the mauve dress with ivory-colored ruffles that my grandmother wore to her youngest daughter's wedding.

Eta, Ethel, was similar to the oldest sister, only slim. A tall, slim brunette. She lived with my grandparents the longest time. She helped my grandmother with cheese-making. At some stage, she took over the major burden of the physical work. I think they were already worried that she's an old maid when she was 20. She got married in 1938, probably through a matchmaker. I can't remember a man around, I guess she never had time for that. A sudden wedding, and she was gone. I have no idea what her husband's name was or what he did. I only know he was from Stanislawow. The wedding took place in Tysmienica. There was a chuppah, a rabbi and dancing. I can still see my grandmother and grandfather dancing a dance at that wedding called broyges, which you could translate as 'angry, upset with each other.' They didn't hold each other's hands only each held a corner of the same scarf. That's where I remember my grandmother in the dress the color of dark wine. The young danced as well, but that wasn't as much of a shock as my grandmother: all of a sudden she's not working but dancing! I spent my entire childhood watching my grandmother work, and that was the only time when I saw her dance.

When I was 4 or 5, my father decided that an only daughter, surrounded by three aunts, a grandmother and a mother, cannot be raised at home only. There was a parish in Tysmienica, where some nuns lived. And they had a nursery there to which I was sent, for a very, very short time. That career was short-lived, for one day I came back from that nursery with a song on my lips: 'Wzieli do wojska Moska pejsatego. Aj, aj. Aj, waj, waj' [a derogatory song about a Jewish man; literally: 'They took one Moshe with side curls to the army. Ay, Ay. Ay, vay, vay.'] I was not sent back to the nursery.

Mostly I hung out at my grandmother's workshop watching how all those products are being made. But I remember holidays away from home which I spent with my mother and grandmother in Carpathian mountains. I was no more than 6 then. The place was called Dora and was located near Jaremcze [around 60 km south of Stanislawow]. Jaremcze was a well-known health resort and Dora was close by, but not that famous, so it was cheaper. We spent our summer there - grandmother came for a short stay and me and my mother stayed longer. I think the house we stayed in was not a guest house, that we simply rented rooms from some local people and my mother did the cooking. What does a child remember? Images. There was a period of storms and my mother was terribly afraid, because thunder really travels in the mountains. So she hid in bed, under the pillow. I sat at the doorstep and watched the lightning, while my mother screamed, 'Come inside and close the door or you're going to be struck by lightning!' I remember a swift-flowing river, Prut. It was shallow, but very rapid. I bathed in it, and once I even started drowning. A local boy, slightly older than me, got me out. That is the only summer away from home which got stuck in my memory.

I went to school in 1936. I guess there was only a Polish school in Tysmienica. I think it had 6 grades. I remember only girls in my class, so there must have been a parallel one for the boys. Or maybe the whole school was for girls, for there was another building. That's all submerged as in a fog. One-story building, without a gym, only some beaten dirt. There were not more than twenty of us in one class: Polish, Jewish, Ukrainian. I think that maybe the Ukrainian children took religion classes at the Orthodox Church and the Jewish children went to the Synagogue. I didn't. About two weeks into the first grade, the girl who was placed at the same desk with me by the teacher, raised her had and said, 'Ma-am, my mother wants me to sit with someone else, not with Reginka [diminutive from Regina], because Reginka is Jewish.' So the teacher moved her somewhere else and I sat with another 'Jewish' girl. I remember another girl from school, Wanda. She was Polish and her family was one of the richest in town. Her father had a large workshop in which he employed people making embroidered sheepskin coats. Wanda found me after the war.

Nothing gave me any problems at school. Even if at home everybody spoke Yiddish, my aunts, my grandmother and my parents spoke very fluent Polish, in fact my father spoke Polish beautifully, and so did my mother. I suppose my aunts graduated from a Polish elementary school. They read a lot to me, as I was the oldest grandchild, and for a while the only one, so I was given a special kind of attention. I can't remember ever having been refused reading or conversation. I learned how to read with my aunts and my mother: 'What does it say here? What letters are these? Why is it pronounced like that?' Nobody ever sat down to teach me, it just happened, fast and easy. Very early I read Heart by Amicis [Edmondo de Amicis, 1846- 1908, an Italian writer, author of didactic novels and stories]. My parents must have given me that. I remember weeping and I remember what my eyes looked like afterwards. I read Guliver's Travels [a satirical fantasy- adventure novel by an English writer, Jonathan Swift, 1667-1745], Mary and the Dwarfs [a story by Maria Konopnicka, 1842-1920, Polish poet and prose writer for children and adults] and so on.

My parents did want me to learn Yiddish, so a melamed came to our house to teach me. But my resistance must have been strong, because the effort was short-lived and I didn't learn anything. My father could easily read Yiddish, and so could my mother, I think. My father was very well-read. At home, there were books in Yiddish, German and Polish. I'm convinced he read the classics in Yiddish: Sholem Aleichem 5, Peretz 6, but there was also Herzl 7. He read in German: Schiller 8, Goethe [Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749-1832, the greatest German poet of the Romantic period], Heine [Heinrich Heine, 1797-1856, a German Romantic poet], not to mention Feuchtwanger 9, Kafka 10, Thomas Mann [1875-1955, German prose-writer and anti-fascist activist, who emigrated in 1933], whom he simply devoured. He loved literature. I can't remember him reading newspapers; I don't know if there were any in Tysmienica.

My father was very demanding in that he took care I don't become a typical 'only child' spoiled by the mother, grandmother and aunts. Most of the time, he called me 'son.' His strictness balanced the women's tendency to see me as 'a poor child, who never sees her father.' Before the war, I remember him as the disappearing man. I remember such scenes as when my mom would wake me up in the middle of the night when I was about 5 or 6. I couldn't understand what she's saying. She woke me to ask me to sit up with her. 'Dad has gone out to a meeting and hasn't come back. I'm so afraid. Don't sleep for a while, keep me company.'

He was a member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine, called KaPUZa, for short. All this information is so shallow... My memories are totally vague. I must have been 4, 5 or 6 when he put some papers under the mattress of the bed in which I slept. That happened at night. Before 1st May, I remember panic, commotion, and then knocking on the door: 'Police! Open up!' Occasionally they invited my father preventively for 24 or 48 hours. I know that he was in hiding for a while. Someone must have warned him that they want to arrest him, so he left home and when he came back it was in the middle of the night, only to leave again before dawn. In the little town everybody knew everything about everybody else. In those times when my father would disappear only to come home at night for a few hours, there was a policeman I can remember as if it was today: Mr. Maciejewski. In terms of appearance he reminded me of Pilsudski 11, for he had a similar walrus moustache. He'd meet me on the street and say, 'Poor child, you haven't seen your father for a long time, have you? Maybe you know when he's coming back? When is daddy going to be home?' Several times my father was in jail in Stanislawow. I visited him there with my mother. We went by train, and then walked or took a carriage to the jail which was certainly not situated in some isolated place.

Well, and I remember when my father was taken to Bereza 12. He was taken in the evening. It was around my birthday, some time in November. Next day my mother woke me up at dawn and we went to the police station. My grandmother was already there. There was a carriage. We stood on the street. They brought out my father and another man - I don't know who that was - both of them in handcuffs. And then, I remember my grandmother, who threw herself at the police like a lioness: how dare they treat my father like that, handcuffed, like a criminal! This is one of the images still very strong in my mind: my grandmother with dark hair and then, cut, and my grandmother gray-haired very soon afterwards. My father spent 11 months in Bereza. My father's imprisonments were very hard for my mother. She was very scared. She had no profession, she was totally dependent. One day I felt like singing and dancing. My mother walked up to me and pinched me very hard: 'Your father is in Bereza and you feel like singing and jumping around?!' For many years later she kept on apologizing for that. In 1937, I sent to President Moscicki my picture attached to my grade report form the 1st grade; I remember it was a very good report [Ignacy Moscicki, 1867- 1946, chemistry professor, politician, Polish President in 1926-39, from 1939 in Switzerland]. I asked if I could please have my daddy back.

Some months later, my father came back home. Polish authorities decided that KPP is not a threat any more, since it ceased to exist [in 1937 Stalin decided to dissolve KPP and it was finally disbanded a year later]. My father came back in the fall of 1937. He showed up early in the morning at my grandmother's house. He didn't come to us, probably not wanting to cause a stir in the house in which there were many other apartments. When my mother found out he is there she ran over to my grandmother's without waking me up or locking the apartment. I woke up to find myself home alone. Where was I to seek help and explanation? I was almost 8. I put something on, though I wasn't completely dressed, and I ran to my grandmother. This is another image I still have in my mind: my father standing at a table in the kitchen. He bent over, but he couldn't quite lift me up. I don't know whether it was because of the emotions or because he was indeed too week and emaciated. He was very thin. The tweed trousers he was wearing were tied with a string; they didn't give him back his belt. And I remember that he couldn't lift me up.

On my grandmother's and mother's food he soon started gaining weight and did push-ups; he said he's learned that in Bereza. He said he has to do that not to get fat. Later, when I was grown up and my father could have serious conversations with me, he told me about doing jumping frogs during assembly and the beds of boards on which they slept and how the newcomers had to first sleep on the concrete floor. He talked about futile work: ditches they had to dig only to fill them in again the next day. There was a song he sometimes sang, but of the words he passed on to me I remember only one stanza: 'Our group walked through the swamps of Polesie, guarded by sharp bayonets. Our hearts beat to this rhythm, the women and mothers cried somewhere afar.' I remember a saying with which they warned each other against snitches; when I chattered to much, he'd say it to me even after the war: 'Don't babble or you'll die from hiccups.' I think the political prisoners were not really separated from others. Sometimes he'd mention a name in those conversations: 'This is a comrade I was with in Bereza.' I can't remember the name.

I remember very well when one evening my father inauspiciously turned on the radio when I was still awake. A Hitler speech was on. I remember, as if it was today, that terrifying shriek and my terrible fear. I have that day, 1st September, right in front of my eyes. Maybe it's a figment of my imagination, but what I see are peasants walking around the town square, many of them holding an ax or a sack on a wooden stick, as if waiting for the moment when they can start looting.

In school, I went up to the 3rd grade in Polish. I remember how suddenly I started studying in Ukrainian, not in Polish 13. The Soviets brought electricity. They quickly put up posts. It all went up in the air, and into the houses, provisionally attached to the walls, and there was light. My father worked in Stanislawow at the time, in the municipal office, called 'gorodskoj soviet' [Russian for city council]. He worked with a man from Dniepropetrovsk, a Russian or a Ukrainian, who came to Stanislawow after 1939 [Dniepropetrovsk: city ca. 700 km east of Stanislawow, in Central Ukraine].

When the war started in June 1941 [the German-Soviet war], we left with that man's family. My father had the opportunity to send my grandparents with us and begged them to go; places on a train were very hard to get. But they flatly refused. So three of us left: my mom, me and my tiny baby sister, who was born in March 1940. My father stayed behind and then followed and tried to catch up with us. I was placed in charge, that is, my father said, 'Son, remember that until you reach the Polish border, your mother will want to get off every time the train stops. Give her the suitcases but keep the baby. Leave it at that; if she insists, let her get off, but you and the baby must go on.'

Our aim was to get to Dniepropetrovsk, together with the wife and the two children of that man my father worked with. But the Germans were moving so fast, such heavy bombing begun, that even before we got to Dniepropetrovsk, we decided to go further. We caught a train to Kharkov [city in North- Eastern Ukraine, ca. 200 km from Dniepropetrovsk], where we were all kicked off the train. It was probably needed to move the army. So we spent two nights at the train station in Kharkov, then another train came. We were getting on it in a mad crowd. My mother climbed on with my sister and two suitcases; I was still at the platform with the third suitcase, when the train started moving. Somehow people pulled me onto that train, by my hair, my hands. I was also trying to hold on to that suitcase, our only possessions... The wife of this acquaintance of my father's had a family in a village whose name I actually remember: Junakovka. But the train didn'd go there. So we got off in Sumy [Northern Ukraine, around 150 km from Kharkov].

There was an 'evakpunkt' [Russian for evacuation point] there, where everybody found some space and somehow survived on bundles. The woman said she will sent a message to Junakovka, that she's waiting in Sumy and a cart will come for us. And so it happened. My father found us in that village, because at each stage, wherever we could, we left notes where we're going. We spent 2-3 weeks in Junakovka, maybe even less than that. We then returned to Sumy and looked for a train, because the Germans were already breathing down our backs. We got on a train which must have been transporting equipment from the factory in Rostov upon Don [ca. 540 km south-east of Sumy].

We ended up somewhere in Kazakhstan [then a republic of the Soviet Union in central Asia] for about two or three months, in a village where Kazakh was the only language you could communicate in. There were no houses there, only yurts. My father engaged in some superhuman efforts over there; he even left us there for a while and somehow managed to get to Tashkent [the capital of Uzbekistan, then a republic bordering on Kazakhstan from the north, ca. 3400 km from western Ukraine]. He decided that would be a good place to take us. So we ended up in Tashkent, where the population multiplied fast, because everybody was escaping as deep into the Soviet Union as they could, at this point into Asia.

Luckily Tashkent is a warm city and it was still warm then. We spent several days in 'sadik' [Russian for a little garden], that is, a small square in front of the train station. You couldn't sleep in that 'sadik,' not even turn away for a minute, because things were pulled right from under you at a moment of inattention. There were bands of children left without care, and adults too, ruthlessly robbing everyone. Since we had a baby with us who was breastfed - luckily my mother was still breastfeeding - a woman took us into her courtyard. There was a so-called 'tachta' in that courtyard: a type of a wooden elevation where one could sit and drink tea, as was the custom. You could place a quilt or spread on it and sleep there.

And then we were assigned an apartment, not in Tashkent itself, but as if in the suburbs, in 'posiolok' [Russian for village]. It was called Lunaczarsk, most likely in honor of Lunaczarski [Anatolij Lunaczarski, 1875- 1933, Russian philosopher and culture theorist, an activist of the Bolshevik party, the creator of Soviet educational system]. There we came across a White Guardist, honestly. He was told, with his wife and daughter, to free one room for us. It was a connecting room, which basically served them as a kitchen. We slept somewhere under the window, on the floor. I remember my mother stood a table on its side to shield us. And the man was a heavy drinker. When he was quite drunk, he took an ax, shook it, and yelled, 'Etoy nochyu ya uzhe etih Yevreyev ubiyu!' [Russian for 'Tonight I will kill those Jews at last']. A neighbor took pity on us. She was childless, her husband went to the front. She gave us a kitchen and a porch and I slept on a coal stove. Later, in Tashkent, I spent whole summers sleeping outside, on a bed made of wooden planks, out of choice. The courtyard was fenced in so I had no problem sleeping there and no bedbugs.

Tashkent was a city made up of many disparate pieces. There was the old Tashkent, where you walked along the narrow streets with no windows facing you, only solid walls. Those were really like mud-huts, made of clay and straw. And there were tall fences, also made of clay. This old part of the city was inhabited by the Uzbeks, who still believed a woman cannot be seen by a stranger. So there were still many women wearing charshafs: gray cloaks, with a stiff net in front of the face, most likely woven from horse hair. There were a few mosques, run down after the years of Soviet presence. There were many Jews there, both local and newcomers. There is a city over there, a very old city of Buchara [around 500 km south-west of Tashkent] where ages ago Jews must have settled. They were referred to as 'bukhariyskiye Yevrieyi,' Bucharian Jews 14. I couldn't tell them from the Uzbeks. Maybe their facial features were sharper and faces less Asiatic in terms of the high cheekbones and slanted eyes. Their clothing was European, I think. But I can't say whether they observed the tradition, whether they prayed and if so, where: at their homes, separately, or together in one of their houses? I remember a joke: 'Zdrastvuyte, tovarishch Yevrey, byvshaya zhydovskaya morda' [Russian for 'Good morning, comrade Jew, who used to be a Kike snout']. That was supposed to be a joke.

Initially, in Tashkent, my dad was a porter at the railway station. Later, in Lunaczarsk, since he knew how to sharpen a razor on a belt, he got a job as a barber in the military hospital for the soldiers evacuated deep East. There was a psychiatric ward at that hospital I was very afraid of; the war gathers a rich harvest of mental diseases. I don't know whether he got references or took advantage of his acquaintance with the staff of the hospital where he was the barber, but later, when we were back in Tashkent, he got a job in the storage room of a military canteen. His job was to move boxes and take crates, sacks and other heavy things off the trucks. My mother, when she decided it was safe to leave my sister in my care, went to help him.

I learned Russian pretty fast. Maybe because I had the Ukrainian base encoded somewhere from my childhood and the year at school when I studied in Ukrainian. So I didn't have problems adapting to a Russian school. My parents still spoke Yiddish to each other, and so did I, as far as I remember. But my father decided that I have to study Polish. So he found - I have no idea where and how - Arnold Slucki 15, to give me lessons. After a few lessons - for which my father paid him as he had no other means of support - the lessons were stopped. My teacher decided it's a waste of money, as I said point-blank that I'm never going back to Poland, so why should I study Polish. I learned how to talk back by then. I believed the only one who wants to go back to Poland is my mother, and only because she wants to be called 'Misses' again. That was what I said. As to myself, I associated Poland with prisons my father was taken to, my father's absence, house-searches... There were many Poles in Tashkent, but I hardly knew anyone. My father must have made contacts with ZPP, Union of Polish Patriots, already there 16. There may have been a Polish orphanage there. I was told there was a Polish school somewhere at the other side of the city. If there had been, it didn't last long; when the Anders Army 17 was formed, those who joined it left with entire families.

I had one close friend. She was Jewish, her name was Ewa, but I can't remember her last name. She came from central Russia, or maybe from the Ukraine. She was a single child, her mother didn't work and her father was some kind of tradesman. We spent a lot of time together: at school, at the school courtyard, at the courtyard at home. I remember singing, talking. We didn't visit each other at home, because everybody had so little space, we were all squeezed into somebody else's house, the whole family crowded in one room. But because of the climate, social life could go on outside year round.

In Tashkent I was first a pioneer 18 and then I joined the Komsomol 19. Instead of going to summer camps we were sent to pick grapes one year and cotton the next. It was heavy and unpleasant work. It must have been after the 6th grade; I was 13 or 14. We were treated as working women, so we got 60, not 40, decagrams of bread a day 20. And the bread was almost white, not like Tashkent bread which was black and sticky and you couldn't cut it. And once a day we got heavy, thick soup in which, unfortunately, sometimes there were pieces of lamb. Over there, lamb was killed only when it was old and fatty and by that time the meat had a very intense, unpleasant smell. But we ate it anyway. Mostly we ate bread and grapes.

I finished 5 grades in Tashkent; I graduated from the 9th grade in 1946. I was old enough then to get a temporary ID. When my parents wanted to go back to Poland I was required to write that I go with them of my own choice. But I fought the idea with all I had in me. I said I'm not going. Because of my resistance we stayed in Tashkent for quite a long time. We finally came back in the summer, June or July, of 1946. We traveled for several weeks. We took mostly freight trains which stopped no one knew where and for how long. After our return we first lived for a short while in Zary [around 400 km west of Warsaw], then Wroclaw [around 350 km south- west of Warsaw] and then Walbrzych [over 400 km from Warsaw, 60 km from Wroclaw]. 21

Out of our entire family only me, my sister and my parents survived. My parents wouldn't talk to us about this war tragedy. I remember once, in 1946 or 1947, my father wouldn't let me into the room where I heard him crying. I think he got a letter or some news. There were two versions of what happened to my grandparents, their daughters and the more distant family members, some cousins, my mother's sister with children and her husband. I also remember that when my parents were counting how many family members have died, I heard - though they didn't know I'm listening - that they have to add the child Eta [my father's youngest sister] was carrying. I don't know if it was even born... So there were two versions. One was that part of the family was killed, shot right there at the Jewish cemetery and the rest sent to Stanislawow. The other version was that they were all shot at the Tysmienica cemetery. I think my father blamed himself for the rest of his life that he didn't make my grandparents come with us, that he wasn't convincing enough. It was tragic, he couldn't take it. 'Stop it! I can't talk about it,' was all he could say. I made a faux pas once, when talk started about reparations for the people who were deported from eastern Poland which became part of the Soviet Union after the war 22. I said, 'Dad, did you hear...' Good God! I have never heard him scream like that, not even when I was a child and did something bad. 'What are you saying to me! You're talking about home?! Where are the people of that home?! What are you saying?! What reparations? For what?!'

After the war two of his aunts were found. I don't know what their names were, I don't know whether they were grandmother's of grandfather's sisters. They must have emigrated in the early 1920s and lived in New York, in Bronx or Brooklyn. Before the war my father or my grandmother used to send them our pictures. After the war my father began corresponding with them. When they found out that we lost everything, that nothing survived, they sent us back what they had of the pictures: those from my father's youth and later ones from after Bereza; mine as a little girl in Tysmienica. My father sent them our post-war pictures, among them one from Walbrzych where the four of us can be seen posing very properly. Those aunts died in the 1950's or 1960's, one after the other.

The return to Poland meant I felt a stranger again. When a few days later I went out on the street and heard a group of youngsters speaking Russian I followed them and asked, 'Rebiata [Russian for kids], you're talking about school. Is there a soviet school somewhere here?' They showed me. And I went straight in, without even consulting my parents, and said I'm Polish, recently repatriated, and I would like to finish their school and take my matriculation exams there. No problem, they said. So I took the news home. There were many students, children of officers; I was the only non-Russian student. Two students in my class, a boy and a girl, were much older. I think they were in active service, for they wore uniforms to school. I finished 10th grade and took my matriculation exams in 1947. The exam covered lots of subjects: both written and oral exams in math and Russian. But there were also: geography, history, physics, chemistry, and a foreign language, I can't remember which. The newly repatriated young people didn't have to take exams to college. Anyway, I didn't take one to study medicine in Wroclaw.

In Wroclaw I lived for a year in a Jewish dorm. There were two: one for students, into which I didn't get for some reason, most likely because I was late signing up; and one for working class youth, where I lived. It was in the center of the city, at Olawska street, I think; We walked the paths trodden among the ruins. The dorm building had two floors and an attic. Rooms for boys and girls were separated by floor. People who lived there were very different from each other and of diverse ages. Some of them worked only, others took college preparatory courses. I lived in a room for four, but there were also rooms for six. All four of us were students. One was a dentistry student, two were students of some humanities departments. We got three meals in the dorm. After the wartime diet, I didn't think of those as bad meals, but they probably weren't very high quality, even if supported by Joint 23. I remember every Saturday we had dinner all together with singing and recitations. I'd describe the conditions as rather Spartan. There was central heating, but it was not particularly warm. There was hot water once a week.

My parents remained in Walbrzych. There was a bathroom in their apartment. I remember my mother, by then more than a 40 year old woman, coming out of that bathroom and saying 'A'mekhaye! [Yiddish for happiness, bliss]. That was one clever bourgeois who invented the bathroom!' My mother didn't work, she took care of the house. She never let go of the Jewish ways of cooking. But we ate every kind of meet, also pork. My mother never used recipes. She didn't let me into the kitchen, because you needed to save and there was always the danger I would spoil something, or make a dish not to her liking. So if I did anything in the kitchen it was as a helper, peeling vegetables, mostly. When we were in the kitchen together, I'd ask her: 'How much of that did you use? How much of this does one put in?' To that she'd say: 'As much as it takes, you'll feel it in your fingers.' Not particularly precise, but for her it sufficed. I remember there was matzah at home after the war. But I don't know where it was from. I know that the Jewish Committee 24 in Walbrzych did distribute matzah.

My father was the chair of the local Jewish Committee in Walbrzych [in the years 1946-49]. It was an organization in which Jews gathered to help other Jews 25. At the same time my father made many enemies, because he tried to persuade Jews not to leave Poland. He argued they should stay, because Poland is going to be a different place. After the Kielce pogrom in 1946, however, I'm not sure how many there were whom this argument would stop from leaving 26. Everybody who could, who had some family, who found sponsors, thought about emigrating.

My father constantly preached internationalism to me. I remember in 1952, personal ID's were being issued for the first time. Up until then we had no documents. My birth certificate or its copy arrived with an error, most likely caused by the clerk's haste or a simple mistake. My name on it was Rena Fischbein. 'Dad, I said, we have to correct his, one syllable is missing.' I'm telling this story to show how paranoid my father was after all. He glanced at me and said, 'You know what, let's leave it like that. Maybe Rena sounds better than Regina.' He didn't say out right that Regina Fischbein sounds rather unambiguous [i.e. explicitly Jewish]. So that's how I became Rena. From 1952, all my documents say that. But at the time, that didn't really matter, to a person who was busy studying, falling in love...

At the beginning of 1948, I interrupted my studies after the first semester. I was aware of how poor my Polish is and how little physical, chemical and anatomical vocabulary I had I felt really bad throughout the first semester, because all of the assistants from the Jan Kazimierz University in Lwow were very aware of my russicisms 27. I felt completely disheartened and I decided that I had to master that language if I didn't want to be treated as an alien, an outsider, a second-class citizen. For that's how I felt. Not because of my background, not at all, only because of my pronunciation and my vocabulary. I took a leave from the University and studied, read lots of Polish books, sometimes even copying. I decided to repeat the first semester. I finished my second year in Wroclaw and in the academic year 1950/51 I came to Warsaw, to my parents. They moved to Warsaw at the beginning of 1950. The party had suddenly remembered my father 28.

At first, my father worked for NIK in the Department of Personnel and Training [NIK: Supreme Chamber of Control, which controls the activity of all state institutions]. Then he worked at the headquarters supervising Construction of Housing for Workers. My mom didn't work, she was always mom. My sister, born in 1940, lived with them. We didn't have much time together, because when I turned 23, in 1952, I got married.

We met as students of medicine. My husband is my peer. His father's family was from Warsaw, for generations. His mother found her way to Poland only after the Revolution, in 1920. My husband's grandfather was a landowner in the Kielce region [around 160 km south of Warsaw], but I don't know that side of the family very well. After some conflict with his mother and siblings, he left for Russia. There, he married a girl from a Russian- Courland family. My husband's grandmother had musical education and taught, as she used to say, jokingly, at some 'Uchilishchie Blagorodnych Dyevic' [Russian for 'a school for well-born ladies']. After the Revolution they found their way to Poland. The grandmother worked giving lessons to opera soloists. She even had the honor of playing with Szalapin [Fiodor Szalapin, 1873-1938, a world-famous Russian bass opera singer], during one of his two visits to Poland, in Warsaw. My husband's mother died in the Warsaw uprising 29, when he was 14. My husband followed in her footsteps and became an assistant at pathological anatomy. Then he worked for the Institute of Oncology, doing research in a purely theoretical field of radiobiology.

Initially we lived separately, with our respective families; later we moved in together. In 1953 our daughter, Helena, was born, and in 1955, our son, Piotr. After graduating, I worked as a pediatrician at the local public clinic. I was aware how little I know in practical terms. Until my son was born, I did volunteer work at professor Brokman's Pediatric Clinic at Dzialdowska street. It was all rather hard. Then I had a year and half break in work, I simply couldn't manage the so-called house help any more. Then I begun working as a school doctor.

We had a lousy apartment in an annex: a room with a kitchen. Then, in 1955, we moved to the Old Town [the oldest part of Warsaw completely destroyed during the war, to be successively rebuilt] where we had two good rooms: one was occupied by my father-in-law, the other by the four of us. It was funny how that room consumed more and more furniture: a piano, a wardrobe, a bed, another bed with shelves attached, and a cot we folded out for the second child. My husband came back home from various places of work when he was sure the children were already asleep. He always valued his work and worked a lot. In 1965, we moved to a bigger apartment, in the center of Warsaw. It was a luxury to us: four rooms; together with the kitchen we had 54 square meters.

When I got married to a Pole and my children were born, I started learning the traditional Polish holidays: Christmas, Easter, and the foods which one is supposed to prepare for them so that at school my children could talk about the same things other children do. I remember the holidays when my husband was on a longer stay abroad in 1960, 1961. As it usually happens when times are harder, both of the kids were sick all winter, particularly my son. When I got the Christmas Eve dinner ready, it turned out my daughter has a high fever. My father-in-law looked at me, at the table, at the dressed Christmas tree, and said, 'What are we going to do? Celebrate Christmas just the two of us, with two sick kids? Why don't you call your parents, maybe they'll agree to come?' My parents did agree and my mother even brought her famous, delicious jellied fish. But when she entered the room and saw the set table and what's on it, she stopped in the doorway and said, 'Ok, I did the fish. But who did the rest?' She was always frank and critical of my skills as a housewife. My father-in-law defended me, 'There is only one woman in this house and she did everything.' I learned what to do and how to do it just by watching. My mother did not celebrate Jewish holidays after the war. From time to time she made one of the lavish Jewish baked things, for example the extraordinary strudel, like the one she used to make before the war.

My sister spoke Polish to my parents at home. She has a very lovely name, Uliana. This name exists in Ukrainian, but she got hers from somewhere else, from Ulyanov, of course [the real name of Vladimir Lenin]. My father called her Jula or Julek [male version]. After graduating from the 1st year of Chemistry at the Warsaw Polytechnic, she got a Ford fellowship and she went to college in the US [Ford Foundation, established in 1936, is the largest private foundation financing higher education and research]. Initially, she planned to go for just one year, but then stayed for three. She never had any problems at school because she was very smart and always a good student. After getting her degree, she taught English at the American School, run by the American Embassy in Warsaw. She married a Jew from Lublin [180 km from Warsaw]. His father fought with the underground partizan army during the war, and the husband spent the war in Siberia with his mother. His name is Wlodzimierz, after Lenin [Polish version of Vladimir]. I can only remember the last name he got after the war, Gabara. He worked at the Polytechnic. My sister worked for Forum [a weekly published from 1965 on, with reprints of foreign publications] as an editor of the culture department, particularly English. In 1968, the chief editor said to her that it would be much more convenient for him and more pleasant if she resigned from her job herself instead of him having to fire her 30. And if she wouldn't, he would have to. Her husband got the same offer at the Polytechnic. So they left. First they went to Vienna, for a short time. I think they were helped by one of their acquaintances from the American Embassy. Then they went to the States. At first my sister taught Russian and got a PhD in literature. Her two daughters were born there: Rachel in 1970 and Ester in 1972. My brother-in-law's parents also left Poland. They went to Israel in 1969 or at the beginning of 1970.

My father worked at the Agency for Peace Uses of Atomic Energy. When everything started in 1968, he got retired and removed from the party. I already had children and was very worried, not about what would happen to me, but about the kind of life they were going to have here. I thought about leaving the country. But I have never considered leaving without my parents. First I had a talk with my father. He was the spiritual guardian and the one who could be relied on to solve problems. And he said, 'If you are worried, and your Polish husband is willing to go, then go. But I am not going. Even if I know that you and Jula love me very much and that you will do everything to support me and your mother, I am not ready to depend on anyone's generosity for my living, even yours. Nor the state's. My retirement pension will suffice for me and your mom here; it's modest, but we don't have great needs.' So I stopped thinking about leaving. After he was removed from the party, my father wasn't doing very well emotionally. He worked for the Jewish Institute 31, but I think he worked only as a volunteer. He died in 1975. My mother died earlier, in 1973. They are buried at Okopowa Street, at the Jewish cemetery. I visit their graves whenever I can, but not always on the anniversary of their deaths.

I didn't have problems because of my background. I had an inconspicuous position at work - most of my professional life I worked as a school doctor. When I now think about my work, I'm glad I worked where I did, in Praga [a district of Warsaw on the right bank of Vistula, traditionally perceived as poorer and run down]. I worked there for about 20 years, until I retired. I think I was needed there and useful. Most likely I wouldn't have been needed in the same way, had I worked in the center of Warsaw, among children whose families were well off in comparison. My husband, in addition to his professional work, was interested in Chinese culture; then switched to Japanese. He had some professional friends in Japan, at whose homes he was always welcome. In April 1980 he went to Japan and there he waited for a British visa. In London they were holding a 5-year contract for him, so they vouched for him and he got the visa. He's been living in London since 1980, where he worked until retirement. He's still studying Japanese. I visited him there once or twice. And always came back.

Both of our children graduated from music school, both as violinists. After high school, my daughter applied to the English Department, but didn't get in. She went to a school which taught typing and secretarial skills, and did very well there. She got a job in the headquarters of an office dealing with import and export of agricultural tools. In the meantime, however, she studied, trying to get ready to apply to the Department of Japanese Studies, but kept it a secret from us. She got in very well and studied there for three semesters. Meanwhile she got married and had a child in 1976, Karolina. Then she divorced. She met a Swede in Poland and left with him in 1979. She learned Swedish and got a job as a social worker, taking care of people who are ill and incapacitated. Later she worked for a while as a pedicurist - not esthetic but curative, which is especially important for older people, people with diabetes. She had to give it up because of eczema. For a long time now she hasn't worked. She has three children. My oldest granddaughter, Karolina, went to a two year school for managers of horse stables and then studied for a year to get a teacher's diploma. The boy, Bartek, is 25 today. With some friend, he established a small computer programming firm. The youngest, Weronika, is 20, just graduated from school and I don't know whether she's started anything yet. Karolina understands a lot of Polish, the younger two not at all. But since they teach English very early at school over there, and grandma has learned to speak English in her old age, that's how we communicate. As far as our Jewish background is concerned, my daughter knows. When she was asked, back in Poland, about her background, she'd say she's 'a mutt, and to make it even better, of two breeds.' When she came to Poland on a visit and saw some indecent things written on the walls or heard them said, she got very angry. How much does it matters to her in Sweden, I can't say.

One of the happiest days of my life was the day when my son gave me his matriculation certificate. He must owe it to his talents and good memory that he somehow got through high school and managed the matriculation exam. He picked medicine and, as it turned out, he treated his studies very seriously. He was a very good student; indeed he worked hard. He specialized in anesthesiology. He got married. His wife studied at the German Department; then she taught German at Warsaw University and did some translations. In 1984, their daughter Agata was born and in 1986, Mina. In 1991, two years after he did his PhD, my son went to the States on a scholarship. His family joined him, but my daughter-in-law didn't like it there and after 10 months she returned to Poland with the children. He started with what they call an internship. Then he got residency, which comes down to picking a specialization and taking an exam to become an independent doctor. He did that in Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, one of the 5 best hospitals in the States. He found a job in Seattle and settled there. He still works there. Now he trains his own residents, he's an Associate Professor. He is glad he doesn't work for a private group, where you work without end and make money without end. He said he is tired of the satisfied American life and now he's joining the Doctors without Borders [Medecins sans Frontieres: an independent humanitarian organization providing help to those who need it irrespective of race, religion and politics] for the third time, giving up his holidays. This time, he is going to Nigeria. He's already gone to Thailand and Liberia. He got married a second time. His wife is American born, a radiologist. His older daughter Agata is in a very good college in Rhode Island School of Art in Providence. She intends to be a graphic artist. And she seems to be doing very well, as she finished her first year in college with straight A's. The younger daughter, Mina, passed the matriculation exam this year and got into the school of Management and Marketing at Warsaw University. They both know what their background is and I doubt they'd have any problem saying to their friends 'my grandmother is Jewish.'

From 1991 or 1992, I have gone to the States every year, spending more time with my son than my sister. My sister lives in Richmond. Her husband works at Du Pont [the world's largest chemical company] as a polymer specialist, very high in the company's hierarchy. Both daughters did Comparative Studies: Rachel French-Russian and Ester Spanish-English, I think. They both teach at universities, the older one started at Yale and now teaches somewhere in Georgia and the younger at Duke in North Carolina. Rachel got married last year, Ester a year before. Rachel's husband is half-Jewish, half-Italian and works as a historian. Ester's husband teaches painting and considers himself Mexican, because he was born in Mexico.

My sister doesn't teach any more. She organizes international student exchange at the university in Richmond; they have students from all over the world. She speaks English as if she was born there, and also knows Russian and Polish. Three years ago she went with a group of students and teachers to Kiev [the capital of the Ukraine] and Lwow. I flew into Lwow to join her and from there we went to Tysmienica. I have only bad memories from that trip. Somehow it proved beyond my emotional capacities. I completely spaced out. And we didn't organize this trip very well. We needn't have been accompanied by the two men, particularly one who was very old and very sick. They were Jews who had lived there all their lives. They survived the war and came back to their old haunts. We spent one day there. Of the places most dear to me none survived. Where my parents' house was, now there's community housing in total disrepair. My grandmother's house is also gone; after the war it housed the police station. I didn't get to the Jewish cemetery, I didn't know whether it exists. A woman whom we talked to, kept repeating, 'Don't go there, don't...' It is probably grown over with weeds or turned into an animal pasture. No trace is left of the synagogue or the Armenian church or the Polish church - there is only one wall left, probably from the bell tower. Only the Orthodox church survived right next to the town square and the school did, but we couldn't go in, because it was closed for the holidays. And it turned out that the town square is tiny, when everything seemed so big before the war. The whole frontage looks terrible. Everything was dirty, run down, stinking in the hot air. A total nightmare. I wouldn't go there again, even if I had more time to prepare myself. I used to plan to go to Tashkent, but then the great earthquake came [in 1966] and I was told that Tashkent is a completely different place now. So there is no point in going there for sentimental reasons, for there is nothing left.

I never went to Israel. My husband did go, on a scholarship, to the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot [around 20 km from Tel Aviv]. Later my sister went to Israel from the States, several times, because my brother-in-law's parents were still there. I never carried banners or wrote on my forehead who I am. Only whenever there was the occasion for it, I openly said who I was, without leaving any ambiguity. And that must have taken away other's courage or gained me some kind of respect. When there was a larger group that would start on Jewish subjects or Jewish jokes which I didn't like, I would say, 'Excuse me, I don't want to spoil the fun or interrupt the conversation. I am Jewish and I will leave not to disturb you. Please continue.' That would cause consternation. It was always amusing to observe how people were backing out. 'Oh, but I am full of admiration for the Jews. What a country have they built for themselves!' To me, Polish anti-Semitism doesn't amount to slogans written of the walls and fences. The Jew has suddenly become the popular subject. But what does the figure of the Jew in the souvenir shop hold in his hand? A coin, or a little sack, or there are coins on a table in front of him and he's counting them. I've never seen a Jew bent over the microscope. This is not done by a punk who goes around writing things on walls, this is done by those who deem themselves artists.