This photo was taken in the Jewish cemetery of Des, some twenty or thirty years ago, they said a Kaddish for the dead. Those are buried here who died in the ghetto, and when they were dig out, people recognized them. There are separate graves, and there is a common memorial too, with the names of all those persons about whom it is known they died in the ghetto. The first from right in the first line in my husband [Fulop Grossmann], next to him, on the left is Elek Mund, the fourth from right is Mica Bilbaum, next to her on the left is Goldstein, then the person wearing sunglasses is Emil Nasch, next to him, a little at the back is the rabbi, doctor Neumann [Dr. Erno Neumann, Chief Rabbi from Temesvár], the second from him - behind the child on the right - is my friend, Ella Motlai, the first on left is Edmund Hirsch, the second from left, in the first line is Herman Nemes.

In fact at the time of deportations my husband wasn't in Des, he was doing work service, only his wife and his family was in Bungur. Bungur is a forest near Des, the ghetto was there. After the war many dead were dig out, who had died in that ghetto, so they buried [the bodies] in the Jewish cemetery. There is a place in Des, in the Jewish cemetery, where a stone is placed, they wrote on it the names of those they dig out. To be honest I never went to Bungur. We never went there, never in our life. My husband told me that when he had been in Budapest for work service, people had been stopped on the street, and if they had been Jews, they had been taken to the banks of the Danube and shot in the head. He jumped in a barrel, that's how he escaped. But in that very moment he said to himself, if he ever had a son, he would never let them circumcise him.

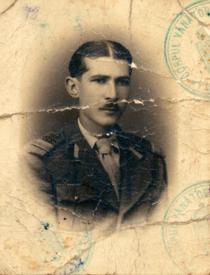

My husband knew many things on Jewry. He could do 'lajnolas' [K'riat HaTorah, reading the Torah] as well. It is a very hard prayer, just a few know it Romania, he knew it. My husband had as much knowledge as a rabbi. He knew everything about the Torah, everything. He came from a very religious family, his father was one of the most religious men in Des. His father didn't come to this synagogue, they had a separate synagogue, a Hasid one. My husband could read from the age of four. He was four years old, and his father took him out from the bed to learn, to read. My husband wasn't Hasid, but he had a great knowledge, since he was a very intelligent man, he could comprehend everything very easily. He attended only the cheder, but he learnt individually. He knew as much as a yeshiva student. Everybody was wondering how he knew so much on Jewry. He was always learning. He knew everything. But these communist ideas came after the war, so he switched [took on from the communist ideas], he didn't observe it [religion] anymore. But he regretted it deeply when he got old. It hurt him a lot that he became estranged. He felt very much annoyed for having left religion. He had his prayer book in his hands the whole after-noon, each day. He realized finally that he belonged to Jewry. Especially when blows hit us, when Erika fell ill, he [my husband] fell ill as well, and it was then that he realized that one shouldn't abandon the Jewish religion, and one shouldn't become estranged from Jewry. He kept on saying that: 'I quitted religion, and blows came. We abandoned the religion, maybe that's why blows are hitting us.' I always said that one shouldn't abandon their faith. Can it be a good or a bad religion, but we were born in it, we have to carry it on.

[In his declining years] He was the soul of the synagogue. He was proficient, he could read everything from the Torah, he knew the explanation for everything, the reason for everything. It was always him who read out from the Torah, who prayed. When he got old, he was always reading and learning at home as well. He had large books; I brought a lot of these to the synagogue, so that if I die, they won't get lost. But I still have a few I don't want to squander. My husband was a very clever man. You have to give it to him. He had a wonderful handwriting, he could bind books marvelously, everything he put his hands on was done, he was so good with his hands. I had a shabby prayer book, he bound it so skillfully. He rebound many of our books, and he rebound the books in the synagogue as well at his old age.

When my husband died, I set shiva, as I did, but not quite as I should have set. Because sitting shiva requires that you have a relative so that you can sit shiva. One has to sit shiva for one week or eight days, and [during this time] somebody has to come to cook, to look after the house. That's the custom. People come and pray at you, in your house, it's about sitting shiva. But since I had no one [relative] left... There wasn't anybody who could have recited a prayer at the funeral, nobody said anything. My son recited the Kaddish, we looked for it in the book, and he recited it. That was all.