Edit Grossmann (nee Grosz)

Dej

Romania

Date of interview: August 2005

Interviewer: Emoke Major

Edit Grossmann lives alone in a two-room block flat in Des, where she welcomes everybody who passes by, because she likes to converse. She’s a friendly, open-hearted woman.

Her skin is tight, which is typical for cheerful people who always smile, but her snow-white hair bears witness to her advanced age, and her swollen wrists indicate that she worked hard during all those 83 years.

She likes to use youngish, merry colors in her clothing.

- My family background

My grandparents on dad’s side originated from Upper Hungary, from Satoraljaujhely. Their children were born there, but they got to Nagyenyed before World War One already [in around the 1890-1900s]. They didn’t have any relatives in Nagyenyed, only in Satoraljaujhely, the large family basically lived there.

They came to us, to visit us, I remember one called Margit came, she was a very beautiful woman, and other visitors came from the family, while my grandmother was alive.

My grandfather was called Jozsef Grosz, Izrael was his Jewish name, we called him Zajdi [nickname for Zajbl]. [He was born approximately in the 1850s.] All I know is that he worked for a German company, he was walking all over the woods. In those times, if a wood was cut down, it was compulsory to plant a new one.

That was my grandfather’s job, planting woods. And this company also transported tan to Germany. The tan was employed in leather industry, they pulled down the bark of young trees, the tan, they soaked it, and processed the skin using that.

[Editor’s note: Tanners’ bark – the bark of certain tree species used for the tanning of raw skin. (In Hungary primarily the barks of oak trees and spruce were used for tanning, generally the bark of 15-20 years old trees).]

Mammy always used to say that tan was a very good medicine; it is very good against rheumatism.

Once my feet were aching, they got cold, and I immersed them into tan-liqueur. Mammy boiled the tan, the bark of the tree, poured it into the timber tub, since back then we had tubs, not plastic bowls. And she told me to put my feet into it, and mammy kept on adding hot water to it. I kept them there for an hour, I couldn’t stand still, but she wouldn’t let me go.

My grandparents had a small house [in Nagyenyed], they had a cow, and they had gooses. They sold the cow, and they sold the house to buy another one, they placed the money into the bank – I don’t know which bank it was, but it was in Nagyenyed –, and they lost all their money.

This happened by the end of World War Two. Then the blow-up [failure] of banks was at fashion. So they became very poor. They were left without a house, they had no cow anymore, they lived in lodgings after that.

Grandfather Zajdi died in around 1925 of Spanish flu, he was old, some seventy years old. Many people died of this disease during World War One as well, one of my father’s and one of my husband’s siblings died too.

[Editor’s note: Spanish flu – the first large-scale pandemic of the 20th century, the Spanish flu had symptoms similar to the influenza’s; it had 20-21 millions of victims between 1918-1919. For example in Hungary 44 thousand people died of this disease in October 1918.]

I couldn’t tell what my grandmother’s name was. Babi, that’s how we called her, we didn’t know any other name. My grandmother had her hair cut, she didn’t have a wig, she wore only kerchiefs. She always wore a kerchief. She had two kerchiefs on her head.

First she covered her head with a cambric kerchief, she tightened it, tied it behind, then she put on one more kerchief – it was rather grey –, she tightened it in the front, not behind. [Editor’s note: Orthodox married women covered their head with hat or kerchief – or according to a custom spread during the 19th century with a wig (sheitl) – for decency, because the uncovered hair is considered to be a form of nudity. The tradition was that prior to the wedding the bride went to the mikveh, where her hair was cut.

After that nobody could see the hair of a married woman except her husband. In principle blessing should be said or a ceremonial carried out when a married woman is present, whose hair is not covered. Today Orthodox women too cover their head only in the synagogue.]

And she had a big shawl on her shoulders during winter. She wore dark-colored clothes. She wore a skirt, it was pleated a little, and a long-sleeve blouse with a little collar. And she always had an apron on, it was also dark-colored, I don’t know why she always needed that apron.

That’s how religious women were dressed in those times. Not my mother, but Babi yes. And they wore black shoes, mainly laced-up boots. Now, when I remember all this, I always start to think about it, that really, why they always wore these boots.

And grandmother had a short jacket, it was shorter than the skirt, that’s what I remember. When she went to the synagogue, she was dressed up properly, she had nice woolen dresses, which were pleated. I can still picture my grandmother. I resemble her a lot.

But she was so ugly, that I always used to say: ‘I wish I won’t become so ugly!’ I became just like her. I have dental plate, she didn’t. Well, if one doesn’t have a denture, that person is very ugly. She was eating apples, I remember so well, she was scratching it with a knife.

Of course I didn’t like that. She was very-very religious, she taught us a lot too. We weren’t allowed to start breakfast, until we recited the ‘Majdi’ [Modeh ani]. The Modeh ani is the morning prayer: ‘Baruch ata’ [Editor’s note: Barukh atah (Hebrew, meaning ‘Blessed are you’) are the first two words of the starting formula of blessings.

We can’t guess which blessing Edit Grossmann refers to from these two words, because every blessing starts with them.], then ‘Modeh ani’, one has to recite it each morning, one must eat only after that, it is forbidden to eat before.

[Editor’s note: Modey ani, Mojde or majdi (Ashkenazi), meaning ‘I offer thanks before you’: short prayer recited upon waking in the morning: ‘I offer thanks before you, living and eternal King, for You have mercifully restored my soul within me; Your faithfulness is great.’ It is a tradition that the soul temporarily leaves the body of a sleeping person, and it gets into the guarding hands of God, then at awaking it returns. Children are taught this prayer at the age of 3 or 4. ‘Modeh ani’ is an act of thanksgiving for the return of the soul, it doesn’t contain the name of the Eternal, and it doesn’t contain a blessing formula either. The reciting of this prayer is followed by the ritual hand-wash, which cleans the awakened man from the impurity of sleep, after that the blessings containing the name of the Eternal and the general blessing formula can be recited.]

Well, my sister didn’t want to recite it, she said she had already recited it once. My grandmother was a clever woman, because she was reading, she always read the newspapers, she was asking dad to give her the newspapers. Daddy was getting the Hungarian newspaper, I don’t remember which one. And it’s interesting, that she was already eighty-seven years old when she died, and she was still reading, without glasses.

Babi lived with us too when I was ten or twelve years old. But she was causing a lot of trouble, because we weren’t religious enough, and she demanded the religiousness extremely severely. That we should be very religious. For example if we cut the poultry, no matter how we proceeded, it wasn’t the right way.

She found deficiency in everything. Mom didn’t take out this or didn’t take out that properly, and she didn’t salt it this way or that way – she checked everything, she was very-very religious. Because after the shochet cut down the poultry, it had to be torn. And after we tore out the feathers, it had to be burnt.

We brought out paper in the yard – I still remember that I was bringing out the paper –, we lighted it, mammy brought the poultry, and we rotate it. We didn’t put it on fire, just let the flames reach it a little. I can’t recall how we called this [process], though it had a name. But it’s very good, everybody can do it.

I still do so [I hold the poultry above the flames of the gas-stove], it’s very good, the poultry has a different taste. After that we cut it up, and mammy put it into a bucket. And it would be there in the bucket, in water for half-an-hour. Then we took it out from the bucket, and put it on a plate, we had separate dishes for that.

And we had a large basket for salting, we put it on the basket [with the plate], and salt it abundantly. It stayed there for an hour. After that one had to throw water over it three times so that the salt would be rinsed. And then we scalded it, and we had to stir it a lot to take out everything, not to leave a drop of blood or a vein in the poultry.

When grandma left from us, she lived with one of her daughters, Zali in Nagyenyed. Zali was left alone, my grandmother was alone as well, and so they lived together, until grandmother died. Grandmother died at an advanced age, she died when she was eighty-seven.

There were five children in my father’s family, there were two girls and three boys. They were poor as well. All of them lived in Nagyenyed. One of the girls, Zali Grosz was the eldest. Zali had a daughter, but she divorced her husband, and she gave her daughter to a rich family from Kolozsvar, they were called Miligram, and her daughter was deported together with the whole family. Zali too lived in Nagyenyed, she was selling fruits at the market, that’s what she was living of. She died in around 1955.

Gyula Grosz was trading in apple, apricot, fruits. Though his profession was tailoring. He worked with me during the war, I took on orders, and we made trousers together. After his wife died, uncle Gyula left for Israel, because all his children were there. He left some eight years after the war, and lived in Lod.

Uncle Gyula had quite a lot of children: Hajmi (Haim), Erno, Kajmi, Zsenka, Erzsi and Szeren. Hajmi and Erno lived in Lod, their wives both worked at the airport. Kajmi was an upholsterer, he lived in Netanya, he became paralyzed, he died too. Zsenka lived in Nazareth, Erzsi in Netanya. Erzsi is two years younger than me.

Maybe Erzsi is still alive, but I’m not sure, since I lost contact with her. Soon after the war [World War Two] Szeren left for America. She had got married, and the boy’s parents had left for America, and arranged for them too to go there.

Dezso Grosz was unmarried, he lived in Nagyenyed. He worked for a while where grandfather did, he was a woodworker, he was engaged in tan. Then he was trading with all kind of things. [After World War Two] He lived with a Jewish woman called Zseni. Zseni was very ill, she had intense Basedow’s disease [hyperthyroidism], she died in Marosvasarhely, she is buried there as well, I also went to her funeral. Dezso died here, at my place in Des, at the beginning of the 1970s, he had a stroke.

One of my daddy’s siblings, a girl died of Spanish flu. I can’t recall the name of this sister of my father, I didn’t know her, just by hearing; the Spanish flu occurred after 1914, in 1915 or 1916.

But I know that she got married to one called Izrael, and she left behind two very nice daughters, Manci and Iren. Then her husband got married again, and he had three more children. But they were deported, and only one of the girls [from the husband’s second marriage], Sarika came back.

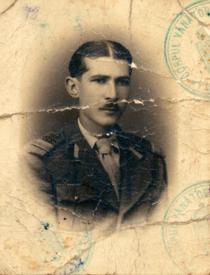

My daddy’s name was Herman, but he was called Helmus, and he was called by his Jewish name too, his Jewish name was Cvi. He was born in Satoraljaujhely in 1890 [but grew up in Nagyenyed]. My father attended the German school in Nagyenyed – there was a German school then –, and he attended the cheder as well.

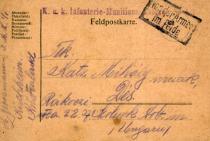

During the war of 1914 he was a simple soldier [in the KuK army]1, daddy didn’t have any rank. First he did army service under the Hungarians, and just when he was supposed to come home [that is: when he should have demobilized], the war broke out, and he went to Russia, he was captured, and he was in Siberia for another four years.

He was in the upper part, on a peninsula. Daddy told me there had been night most of the time, they had had daylight just for a few hours, it was so up [in the north]. And it was very cold. So he was away for seven years. They had a very hard time in Russia, they didn’t have food, but he always told me that Russians weren’t bad people, they always threw them some food.

He also worked for Russians, and they gave him to eat. He worked on the fields, he worked in many places. But he got ill very soon. There were many diseases in those times, in the war of 1914: typhoid, then there were many louses, up there, on the ‘Kolas’ Peninsula where dad was, they even had scurvy disease.

[Editor’s note: Presumably Edit Grossmann talks about the Kola Peninsula.]

The greatest part of the peninsula’s populated area is north to the Arctic Circle.] Scurvy takes out the teeth, this is because of vitamin deficiency, and there were no fruits, there was no vitamin C. They were eating only one kind of food, who knows, they were given some sort of mush, and they got the scurvy disease.

Dad came home with no teeth, later he had a denture made. All of his upper teeth fell out, he had a maxillary denture. He still had his lower teeth. I was laughing, because we used to go to the banks of the Maros river, and once daddy was laughing or sneezing in the water, and his denture fell into the river.

Our domestic was there too, he was called Majsi, he jumped into the water, and took it out: ‘Here it is, Mr. Grosz!’ He had scurvy, he had typhoid, he had all sorts of diseases. And he never regained entirely his health. He wasn’t a thin man, but he wasn’t healthy.

After he came back from Russia, he got married, it was an arranged marriage. Well, back then one didn’t meet a person like today! Formerly it was recommended, there was a person whose job was this, who was called sadhen [shadkhan]. They had a simple rural marriage in Boldogfalva.

Mammy’s father was called Farkas Klein. Zev was his Jewish name, I think Zev is used for Farkas. He lived in Boldogfalva [19 km to south-west from Dicsoszentmarton. In Romanian: Sintamarie], he had an inn. The inn belonged to a Hungarian nobleman – he was a count or I don’t know what –, and they rented it.

But they led a life of poverty, they were surviving in fact, they had nothing. Mammy was little, she was around eight when her mother died. They had an elder sister, Ida, she was keeping the household, until their father got married again. Mammy was quite grown-up when her father died, and a lot of children were left orphans.

In those times it wasn’t usual to have one or two children, then there were six or seven children in a household. There were large families. Back then people didn’t use contraceptive pills, there wasn’t abortion, and it was even forbidden.

They had babies one after the other, there were six-eight children in a family. He had five children from his first wife, among them my mother.After mammy’s mother died, her father got married [for the second time], and he had more children, but those were all boys.

Mammy’s mother was a wonderful woman, I had a picture of her, and once we put it on the loft with its frame, it had an old-fashioned, oval frame, and somebody took it away. We didn’t have room for all the things when we moved here. Mammy’s parents weren’t alive yet when mammy got married.

Only her stepmother lived, she used to visit us, but she was also very religious. The boys were learning profession in Dicsoszentmarton [in Romanian: Tarnaveni], so the [step] grandmother moved to Dicsoszentmarton as well so that she didn’t live alone.

My mother had four full siblings: one girl and three boys. The eldest among the siblings was aunt Ida. Aunt Ida Klein established a family in Erzsebetvaros, a Saxon city [Editor’s note: in Romanian Dumbraveni, 19 km to the west from Segesvar]. Her husband’s family name was Izsak, but I don’t know his other name.

They were extremely wealthy people, because they were traders in leather, they had a leather store as well, they had a nice house, they were well off. In 1941 aunt Ida, her husband and their three children – Erno, Bela and Magda – were forced to move from Erzsebetvaros to Balazsfalva [Editor’s note: in Romanian: Blaj, 60 km to the north from Nagyszeben], when we were going as well to Gyulafehervar, but later they went back to Erzsebetvaros.

They survived World War Two. Aunt Ida and her husband had one more son, I don’t remember his name, but I know he lived in Marosvasarhely with his wife. His wife died during the war, because she was deported from Marosvasarhely. He did work service, he came home, but he was seriously ill, they took him to Segesvar to operate his lung.

He recovered, and wanted to go to Israel, but he got only to Rome, he died there of pneumonia. Imagine that Erno proposed to me! He’s my cousin, and he wanted so much that I became his wife. I didn’t marry him, I said I wouldn’t marry a close relative. My father didn’t want it, my mother did.

Dad said it wasn’t right, he was a much too close relative. Jewish religion doesn’t object to it, but perhaps it’s not good from the point of view of health. Because I would have been afraid of having a child, it’s not too good with a close relative. A long time ago a Hungarian boy was supposed to marry only a Hungarian girl.

A Jewish boy only a Jewish girl. Maybe that’s not too good either. Maybe the change of blood would do no harm. And one more thing about that family, they had to meet only that family, which belonged to the top society. I wasn’t raised like that, and it made me nervous. Later Erno got married to a girl from Medgyes, and they left for Israel, he had a poultry-farm and a vineyard.

When I was in Israel, I visited him with my sister, he told me: ‘However, I never loved so much anyone like you.’ Bela was a dentist, formerly one didn’t have to be a doctor to work within a mouth, he was a technician, but he prepared dentures, he did everything, he treated teeth – it was him who mistreated me.

Magda was a very beautiful, exquisite woman, a real beauty. She didn’t get married, because she wanted to marry a doctor or a lawyer, she didn’t take for a man anyone else. After the war [World War Two] Magda was helping her brother, and a lamp or something she was working with blew up, and she got burnt completely.

She became ugly, she lost so much weight that she weighted thirty kilos. They had a vaulted door, Saxons have such doors, and they never opened it again, nobody was allowed to enter the house. She lived with her mother and her brothers, but they didn’t let in anybody. It was a great tragedy.

Mammy was there, she visited her, and she said Magda was unrecognizable. Later she was in hospital, an American doctor saw her, and took her to America, put her in a hospital there, and they restored her to a certain extent, they put new skin. Magda stayed in America. But she never got married. She was a fashion designer, and she opened some kind of salon, that’s what I heard. She was in Israel for visiting only once, Erno said she had recovered, but one could not recognize her.

One of the boys from grandfather’s first marriage – I don’t remember what his name was – was director at a Romanian-French bank in Brasso after World War Two. He was a learned man, he left for Israel. He had a daughter, Marta, she got married in Israel. I know nothing more about him, because Erika [the daughter of Edit Grossmann] isn’t in contact with her, the family died out, there isn’t anyone I could ask. And mammy had two more brothers in America, I have no idea what their names were, they left at a young age.

The eldest son from grandfather’s second marriage was called Jeno Klein, he was a fitter master in the nitrogen factory in Dicsoszentmarton. Jeno was a very skilful man, he was well up in everything. When something, no matter what broke down in the factory, a machine or anything else, they gave a phone-call, sent a car, Jeno went there and repaired it. He died some fifteen years ago [in around 1990]. He had two daughters, they are still alive, Marta and Sasi, they are both learned girls. They live in Haifa, and they have very nice families.

Jakab Klein – we called him Jaki – lived in Kolozsvar, he was a mechanic in a factory. Jakab had five children, none of them returned from deportation, and finally this drew Jakab mad. He married a disreputable girl, she was his servant, and she ensnared poor Jakab; this woman had two children as well. Jaki lived in Paris street number 5, it was a nice apartment, that woman still lives there for sure. Jakab died in Kolozsvar on 2nd August 1980.

Geza Klein was a merchant, and Odon Klein was a very good joiner. These two boys spent a lot of time at our house, they even lived with us, [when they were young] they lived in Nagyenyed. After they got married, Geza went back to Dicsoszentmarton, and Odon moved to Kolozsvar. Geza committed suicide.

He had a serious brain-tumor, but he had headache so often that he couldn’t endure it, he took some pill, and the poor man died before World War Two. And Odon was operated, also due to a brain-tumor, and he died after ten days. He had a little daughter, who was deported from Kolozsvar together with her mother.

My mother’s name was Eszter Klein, she was born near Dicsoszentmarton, in Boldogfalva. They have very good grapes in Boldogfalva. She attended the school in Kukullovar [Editor’s note: in Romanian: Cetatea de balta, 3 km to the east from Boldogfalva]. I suppose she finished seven grades, this was the custom back then.

[Editor’s note: Eszter Klein was born in the 1890s. At that time in Hungary one had to finish the public school, which had six-grades.]

She came from a very religious family. When daddy came home from Russia, he married mammy. They moved to Nagyenyed, daddy opened a tailor’s workshop, and so we lived of tailoring. We weren’t wealthy people, we were poor. It’s not a shame. It’s not something to boast of, but one shouldn’t deny it either.

That was it. We didn’t have our own house, we rented an apartment with two rooms and a kitchen in Nagyenyed, in the yard of the bank. Mammy didn’t work, in those times women didn’t really work, but she helped in tailoring. But I say the proper place of a woman is next to her children. Because if not, a stranger is needed, right? Or if not, should the street raise her children?

We were only two children, me and my elder sister. My sister, Miriam Grosz was born in 1920. She attended the same school I did, primary in the Jewish school, then three more grades in the Romanian school. She was a much better student than me, she had brains. After she finished seven grades, she learnt hairdressing and manicure.

[Editor’s note: In Romania the elementary education was regulated by the law on public education of 1925. The law provided for the launching of grades 5-7 besides the existing four grades. Accordingly the elementary education was extended to 7 grades.]

I could arrange hair as well, I also had clients, they came to the workshop late in the evening, and I put up their hair. And we had clients we were going to in the evening, after we finished our work, she at the hairdresser’s salon, and me in the tailor’s workshop.

Oh, this is a tale, today if someone said such stories to somebody, that person would laugh. My sister bought curling-tongs, and we were heating up the iron above the Primus, and we put up the hair. Primus was a kerosene-fueled burner, but not that one used for lighting, but for cooking.

We couldn’t even exist without that Primus, we took it with us to Gyulafehervar as well. In the summer we cooked with the Primus. A tea, all kind of things. That Primus was a very good thing! Kerosene wasn’t a big deal. It had a hole, through which we poured the kerosene into the tank using a funnel, there was a screw, we tightened it. It had a rounded burner above the tank, where the flame would go around. It was red, almost every Primus was red.

- Growing up

I was born in Nagyenyed, in 1922, Rajzele was my Jewish name. We were a religious, Orthodox [Jewish] family. My mammy was very religious, so was my father. My parents were very kind-hearted people, very straight, very honest, and that’s what they taught us as well.

There wasn’t such thing that honesty could be lacking. Dad always used to say that one had only one thing in life, their honesty. They brought us up to what Jewry meant, to marry no one else but a Jew. According to the old Jewish religion [that is to Orthodoxy], if a child married a non-Jewish, he or she died for the family, they wouldn’t talk to him or her.

And they performed the funeral as if they buried that person. For us the funeral is not like in Christian religion, where they prepare a festive dinner and I don’t know what. In our tradition they come home from the cemetery, and sit shiva for one week. And if someone gets married to a Christian, they sit shiva for one hour.

Today this doesn’t exist anymore. Today they don’t observe anything. Back then it was a serious matter. This was nonsense as well. These were the ancient dogmas, they were struggling to maintain the Jewry, when it went through so many things, this was the only possibility to preserve the Jewish people, the Jewish race, not to get in a mixed marriage.

Mom was very religious, extremely kosher, she was terribly kosher. Because back then everybody was kosher, to be honest. There weren’t Jewish families who didn’t keep a kosher household. First a family from Nagyenyed brought us the milk, I don’t remember their name. But mammy got angry with the family from Nagyenyed, because she noticed that they put meat in the milk-can.

And so mom said: ‘I’m sorry, I have told you that the milk is milk, the meat is meat. We don’t eat milk with meat.’ After that I was going for milk with my cousin, Erzsi [Grosz]. We had a pail made of tin, we went for milk with that. We carried the pail, a towel and a can with us. We even brought the water from home, we dragged the water in the can – not in the pail, but in the can we brought the milk in –, so that they washed the udder of the cow with that water.

What if there isn’t any well or I don’t know what. They milked the milk in the pail, after that we poured it into the can, that’s how we brought the milk. But we went to the village with Erzsi, I must have been ten or twelve years old, we were laughing so much, we had fun all the way, at least we didn’t have to do anything at home during that time.

We walked three kilometers to the village, I don’t know anymore which village it was, but we crossed the Maros river by the raft. Each day, for eight days. Then they [the villagers] brought us [the milk].

We observed every holiday, we didn’t skip any. On Friday evening two challos have to be put on the table, and covered with a cloth for challah. And the woman comes, she lights the candles. [Editor’s note: Sabbath begins with the lighting of candles on Friday evening; the candles have to be lit half-an-hour before sunset.]

My mother lit three candles. When men come out from the synagogue, they sit down to take dinner, and the father, the husband cuts the challah – they break it instead of cutting it.

[Editor’s note: The first sumptuous Sabbath meal begins after the ritual hand-wash, which is preceded by the Kiddush with the blessing recited over the two breads (challos) put on the table: the head of the family takes off the cloth, puts his hands over the breads, marks the challah which is closer to him with a knife, and says the blessing starting with ‘ha‑motzi lehem min ha‑aretz’ (‘who brings forth bread from the earth’). Then he proceeds to cut the bread at the marked point, dips it into the salt, eats from it, and gives to those sitting at the table.] And they recite a ‘brucha’ [berakhah], a blessing over the bread, they thank God for giving them bread.

Pesach was terrible! Pesach was very-very hard in those times, it meant a great circus. Everything had to be taken out from the house, the house had to be whitewashed, the pockets of clothes had to be turned out, everything had to be cleaned, absolutely everything.

When all the cleaning was done, mom gathered all the chametz – which wasn’t a Pesach food – and sold it. Not for money, this was just a symbol, she gave it as a gift for somebody in the neighborhood. Everything [chametz] left at home had to be given.

We had pasta, if some food was left, cakes, I don’t know what, we gave it. And we gave the house a good seep again, and so the chametz went out, there was no chametz left. What we swept and what we didn’t give away – pieces of bread, papers [which might have touched bread] –, we had to burn it.

We brought it out in the yard, and lit it, burnt it. The day before the last day we didn’t take lunch inside the house, because it was cleaned up, and we weren’t supposed to bring in something. We ate out, in the summer kitchen, no matter if it was cold or hot, there was a stove, and we made fire, we took lunch and dinner in the summer kitchen.

In our house there was a tub for water on a kitchen stool. We replaced each year the water tub, because in the meantime it got damaged. It couldn’t be scoured out, and we bought each year new tubs for cabbage, for water. But at Pesach we brought down from the loft the Pesach dishes, and the Pesach pail was put in the place of the water tub.

We had separate Pesach dishes, a separate pail, separate basket, separate everything, not the same we were using the whole year, God forbid! The Pesach pail was put on the same kitchen stool, but first we put hay on the stool, then plywood or a plank, then hay again, and we put the pail on it. God forbid so that it didn’t touch anything, which wasn’t kosher enough. Because maybe somebody used that plywood, and something touched it, bread or I don’t know what. One had to work so much!

They dug a large pit in the back of the garden – I don’t know why it had to be in the back of the garden –, they put there all the [everyday] dishes; those which were lacking from the Pesach dishes, mortars and things like that had to be koshered to make it usable at Pesach.

First we put soil on the dishes, then we carried out very hot stones – we always had to help –, we threw them there [in the pit]. The stones were left in the stove [in fire] until they got hot, when we took them out, they were burning, they were still red.

We had a pail, we brought them back with that, and we put in the stones [on the dishes covered with soil]. The pail full with water was already there (the Pesach pail was down already), we poured it above it, then covered it with soil – may it rest in peace.

And we left it there. It had to stay there like this for about ten days before Pesach, then we took out the dishes, but we had to scald them so many times, and there was such a great circus… And we always had to kosher the oven, the stove before Pesach. We cooked the food in advance, because we had to eat cold dishes from then on, we couldn’t cook or heat with that oven anymore.

Two days before Pesach we put on the plate of the oven, on the iron a lot of sandy pebbles. We lit the fire, and we took out some coal and placed on it [on the pebbles]. And the fire was burning, and the pebbles were getting hot. And we kept on putting coal, I don’t know how many times we did so, until the oven burnt out.

We were feeding the fire all day. It got cold during the night, in the morning mammy took it [the coaly, sandy pebbles from the oven’s plate] in a pail, threw it, and cleaned the oven. We washed it, treated it with iron-dust. I also did this a few times here, in Des, but then I stopped.

At Christmas we did the last cramming, we cut down the goose, and prepared the kosher fat for Pesach. Because there wasn’t any kosher oil –we didn’t use oil anyway –, and we needed a lot of fat for Pesach. We brought everything used at Pesach from a Jewish store: Pesach wine, Pesach salt, everything was for Pesach.

We bought from there even the pepper. Because it was kosher, they took care that bread didn’t touch it. At Pesach we ate matzah, and we cooked according to the standard Jewish cuisine. We cooked meat-soup, and we put in the meat-soup kneydl, dumplings made of matzah meal, it is prepared with eggs, like the semolina dumplings, but instead of semolina we used matzah meal, and we put some pepper in.

Then we boiled it in the soup, slowly, it was boiling slowly, and it got swollen up. It’s so tasty, it’s very tasty. The roast is exclusively of poultry, we cut goose, we cut duck. For the meat we prepared farfel from matzah [meal], then we had ‘hremzli’ [latkes].

If you don’t know how to prepare it, I will teach you how to make latkes. Now, first you boil two or three potatoes. When it goes completely cold – if it isn’t cooled down, it will stick to the grater – you grate it. You boil it today, and you prepare it tomorrow let’s say.

You put the grated potatoes in a dish, you add three eggs to two potatoes if the potatoes are bigger, or two eggs – well, it depends how it sticks together, it has to be like the ground meat in the meatball –, you put pepper and salt by all means, and you mix it well.

You pour oil [in a frying-pan put on fire], you take some from this mass with a spoon, and put it in the hot oil. But first you dip the spoon in the hot oil, because this way the mass will come off the spoon easily. And it will swell up, it’s such a good meal, and you have a dinner. It is very good with spinach for example.

At Seder we ate it after the meat. A long time ago we cooked borsht soup as well for Pesach, but we didn’t eat it at Seder night. The borsht is very good for the lungs and for everything: the beet-root is soured, strained, and when it is boiling, you pour in many eggs, beat up eggs. It needs a little sugar, pepper, and we put cold potato slices into the hot soup [when serving it].

It is also a good meal. We sour the beet-root. It is a separate circus, the bottle must be very kosher. We had a jar for kosher beet-root. We had to keep water in it for I don’t know how many weeks, and we had to change it I don’t know how many times. But the water had to be boiled first in a kosher pot, then poured in. Can you image that?

We always prepared a cake as well. We didn’t have cake for the first [Seder] night, just for the second night and day. [Editor’s note: Seder night is the first night – in the Jewish Diaspora the first two nights – of Pesach.

The calendar days were calculated according to the appearance of the new moon. When the delegates of the beth din (the rabbinical court) of Jerusalem didn’t get in time to Jews living in Diaspora to let them know when the new moon would appear, it became a custom to celebrate during two days instead of one the holiday specified in the Torah. (Only Yom Kippur remained a one-day holiday due to the fast.)]

And at Pesach we cooked the cake of matzah meal. I still have matzah meal. In those times we didn’t have cookies for Pesach, today they prepare all kind of cookies for Pesach in Israel. Today people are modern; they make very soft flour of matzah meal, and cookies of matzah meal. They even have cream cakes.

We prepared cakes with nuts, mom always baked cake with nut, and a cream in it with coconut butter, it’s like margarine, but it’s made of coconut. Coconut butter. I never ate coconut butter since I left home. We always had coconut butter at home, mom always baked with that, I tell you why. Because we didn’t have margarine back then, and the coconut butter wasn’t milky, it didn’t contain meat either, but one could have eaten it after the meat and after milky dishes as well.

Formerly Seder night wasn’t the same as today, in the [ritual] canteen or at the synagogue. At that time everybody celebrated it at home. My grandmother always came to us for Pesach. And dad always invited a soldier from the synagogue to take dinner, because soldiers were permitted to go out.

He was sorry for them, because he was a soldier for such a long time, so he always invited a soldier. That’s what I remember from my childhood. And a bocher was with us at Seder night – we called him little bocher, because there were big bochers as well.

The bocher was something natural, he was familiar with us, he came as if he went home. That’s a student, bocher means student. There were many Jewish children from Maramarossziget, who attended the cheder in Nagyenyed. The parents were so poor, that they separated from them, they sent them to learn.

There was a room in the cheder where they lived, and families were appointed for them, where they were given meals. Once they ate here, then they ate there, they were given lunch – what people had, a soup, noodles, beans, pancakes –, they were given dinner, and they were given packages for breakfast too, bread with plum jam or something.

That’s why a bocher used to say he was eating only beans, because on Monday he went to a family, well the bocher is coming, so they cooked beans. On Tuesday he went somewhere else, and he was given beans again. On Saturday he went to a family, and he ate there cholent.

People gave him a pair of shoes sometimes, or clothes. There was almost always a bocher at us, he ate at us once in a week, and he always came on Sabbath. No matter how poor we were, we cooked so that bocher too would eat.

In our family at Seder night the table was laid properly, we put small plates for everybody, there were put the charoset and the matzah. Only the person who was leading the prayer [Editor’s note: That is the person who led the Seder night ritual] had a plate with potato, radish, and with parsley as well – because it’s a symbol of spring, and in fact Pesach is the celebration of spring as well –, and we put there a fried neck or something.

At Seder night dad put on a white robe [kittel] and cap, and read what one had to read at Pesach, the Haggadah in Hebrew, and he explained us everything, that why we were eating the radish… Because a child, the eldest child

[Editor’s note: Usually not the eldest, but the youngest child has to ask the four questions, or if there is a boy in the family, then he has to.] has to recite the ‘Manistanu’ [Mah Nishtanah]: 'Ma nistanu halajla hoaze…’ [Mah nishtanah hallayla hazze…], that why that night was not like the others, this night is different, and he asks why we are eating matzah, and why we are drinking wine. In our family the little bocher said the Mah Nishtanah.

The beginning of the ceremony was that they gave us matzah, they gave us potato, everything that had to be given, and we said a broche [blessing] over everything. We recited a broche over the matzah: ‘Majci ani lehunekum melahajrum, anser gil macesz’.

[Editor’s note: Presumably Edit Grossmann refers to the ha-motzi blessing, which is a generic blessing over the bread or grain products used in a meal, and also recited over the matzah.] We didn’t say ‘hurec’, because hurec is for bread, we said: matzah, we recited the blessing over the matzah instead of bread. First we ate the potatoes.

Boiled potatoes, it was cut, we dipped it in salty water, because it meant that they [Jews] crossed the salty sea. [Editor’s note: Others think that the salty water refers to the tears shed in captivity.] Then we had ‘hrajszesz’ [charoset]. Charoset means the result of the harvest: apple and nut and wine, we made a mixture of these. Charoset is very tasty, I like it a lot.

Then we had radish, and we drank wine, they poured a glass of wine for everybody. And praying, praying, and we were already so hungry that our eyes were popping out. And so we ate meat-soup, we had a roast with farfel, and after the meat we ate latkes. On the first night we didn’t eat cake, just on the second night. And we were praying during the meal too.

[It was also during the meal that] Dad recited a prayer, and poured a glass of wine for [Elijah] the Prophet – we called him: the angel. And dad said to one of the children: ‘Go and open the door!’ We opened the door... we were standing. And I was convinced that the angel came in.

One enters into the spirit of religion so intensely that we opened the door, and mammy said: ‘Can you see then that the wine stirred?’ ‘It stirred indeed, the angel came in.’ Like Christians in front of the Christmas tree, they also imagine that the angel is coming, isn’t it? [Editor’s note: Edit Grossmann associates the angel with Elijah the Prophet.]

The matzah stolen of course, we were children. They hid the afikoman by the end of the ceremony already, and we tried to take it out. There were two pillows [put on daddy’s chair], he was sitting on them, [it was hid] between the pillows, and dad arranged it so that one of us could draw it out.

[Editor’s note: According to the Haggadah at Seder night one should lean on one side, and eat leaning the food put on the table. The Haggadah contains directions concerning this in the part beginning with ‘Mah nishtanah’.

The fourth question of Mah Nishtanah is: ‘Why is it that on all other nights we sit straight or leaning, but on this night we are all seated leaning?’ The origin of the custom of leaning is that according to the Roman tradition free citizens with full rights ate leaning on pillows. Jews gained their freedom at Pesach, when they were set free from the rule of the Egyptian Pharaoh.

Leaning on pillows represents the status of freedom. The participants have to lean on the same side, but according to other customs they lean on both sides; however there are no halakhic arguments for this.] It was always my sister who succeeded to do it, ’cause I was so clumsy.

However one of us stole it, then we got something, sweets, after Pesach mom bought us sweets. They were selling candies at Pesach too, Pesach candies, but it was very expensive, we didn’t eat. We stole the afikoman only the first night; there wasn’t any on the second night. And we put aside that matzah, there was a piece of matzah in the bedroom, on the top of the wardrobe. Nowadays they distribute the afikoman, but formerly we put it away. I don’t know why.

The Seder night lasted until eleven o’clock. We had dinner, then there were songs [psalms]. Children came from the neighborhood, and they were singing. And we were eating matzah, charoset, latkes. Mom prepared so much that everybody who came could eat.

Pesach was over, then Shavuot came. It was a simple holiday, it was only a two-days holiday. We had dinner, lunch, people went to the synagogue, Shavuot was a nice holiday. We got new clothes, a summer dress and sandals. It had to last.

At Sukkot we set up a booth, covered it with reed, and we put apples, nuts in golden paper, silver paper, and hung it up. We had dinner in the booth, and had lunch in the booth for eight days. We didn’t go [in the booth] for breakfast, because it was cold, we drank that cup of milk or coffee [in the kitchen].

At Chanukkah we only lit candles, we didn’t organize sumptuous dinners, no. Now they offer cookies in the synagogue, I don’t know what, back then we didn’t have this custom. But we lit candles every evening. And at Chanukkah we played the dreidel game.

The dreidel is so interesting. It was carved out by hand from wood, mainly bochers did it. It had four sides, and all kind of Jewish letters were written on them, alef, bet, gimel... [Editor’s note: The letters shin, hei, gimel and nun are written on the four sides of the dreidel], it had one leg, I think, or two legs, it had to be twisted, and it depended who got which letter.

I don’t remember which the winning number [letter] was, which one was good for winning. [Editor’s note: This game was played in many places; the meaning of the letters written on the sides of the spinning top was: put, take, nothing, all.

At the beginning of the game everybody was given the same amount of matchstick, maize grain etc., everybody proceeded at his turn according to on which side the spinning top fell. That child won, who at the end gathered all the matchsticks, maize grains etc.]

Purim was wonderful. Before that we were cracking nuts for a week, then baking started. Mammy baked three or four cakes. Cake with nuts, she prepared yellow cake by all means – that is normal sponge-cake, it’s just high –, she baked a cream-cake and a cake with honey.

We put some nuts in the cake with honey, I couldn’t prepare it anymore, it is also very good. And she prepared kindli, that’s the most important. The kindli is a cookie of definitely Jewish origin, an ancient Jewish cookie. The dough had to be rolled out, the dough needs some wine, a little honey, some fat, and it has to be rolled out to make it very thin.

One has to put a lot of nuts on it, a lot. The nut is ground, but not with the meat grinder, but with another, so that it becomes massy, fatty. Well, if not, then they press it with the rolling-pin, after they grind it. It has to be heavy. And it requires a lot of raisin, spices and honey and granulated sugar. A lot. And it has to be squirted with honey.

Well, and they roll it on, it’s like the beigli, and they smear it with honey. We made five or six sheets, mammy baked the kindli in two turns with the baking tin. It is a very hard cookie. We strictly had this for Purim, and there was one more, I don’t know yet how that was called, it also has a Jewish name, and it also consists of sheets, like the cream cake, and it also needs nut.

[Editor’s note: This must be the flodni or fluden, which is made of the same sort of dough like the kindli, but they put a filling of nuts, poppy-seed, apples and plum jam between the layers. In Hungary it was a specific Purim cake.] And we made macaroons [Hungarian honey cake], a lot of macaroons, and we baked ‘humentas’ [hamantaschen] as well – well everybody baked it according to her own recipe.

[Editor’s note: The hamantasch is a baked cookie made of leavened dough; they cut it in a square form, then turn it up and fill it with plum jam or sugared poppy-seeds.]

Mom was baking for four days. A large table was full with cookies. And we brought each other cookies. We put on a bigger plate yellow cake, because it looked very nice, we put kindli and everything. We brought it to the neighbors, to this and that, and ‘sleche munes’ [slachmonesz or mishloach manot, sending of portions], that’s how we called it, some sort of gift exchange.

In the evening men went to the synagogue, read the story of Esther, because Purim is the story of Esther. When they came home, we had a great dinner: stuffed turkey neck, or if we didn’t have turkey, then stuffed duck neck, roast, stuffed cabbage [Editor’s note: Of course the stuffing wasn’t made of pork, but of beef.] and cookies.

And we had a big challah. Not sweet, it was like bread, but it was breaded. At Purim they made rounded breads too, and put poppy-seeds on the top. These former holidays were really beautiful holidays. And children dressed up [in masquerades], and they went to people to give them money, gelt.

They came and sing, we had prepared one lei, two lei. Mom didn’t let us go out. We went to my cousin [to Gyula Grosz’s family], she let us go there, but nowhere else. We didn’t even dress up.

There was an ordinary shochet in Nagyenyed, and there was a slaughterhouse. There was a mikveh, we went there to bath, in those times there wasn’t bathroom at home, we went to bath in the mikveh. Otherwise we bathed at home in the washbasin. We had a big-big basin, a big pail, that was the fashion then.

We warmed up the water in the wash-pot, we poured it in the basin, and we set in it. In the mikveh the water had to be running water, not standing water or water from the tap. It came from the river, there was a boiler where they heated it, and brought that [through a conduit] into the mikveh.

There was a woman called Mrs. Kiss, she was selling the tickets, we paid to her for the mikveh, and she surely cleaned up, and there was a mechanic who handled the boiler. There wasn’t a separate mikveh for men, they just went there at a different time, and in the meantime the water was let out, they poured fresh water, the mechanic was changing the water.

There were about three bathtubs – I don’t remember anymore whether these were ordinary bathtubs or wooden tubs, but I think they were wooden tubs –, but mom didn’t like tubs, she rather took us down to the mikveh, we took a bath there, we washed ourselves with soap.

Then they let out the water, because they changed the water continuously. It wasn’t too large, but its diameter was more than two meters, there was room for the three of us, me, mom and my sister. It was rounded, we went down some stone stairs, and it had an iron edge we gripped.

The water came up to the waist or chest. But it was such a great event for me, I was so happy when we were going to the mikveh. It was such a great splash, I liked it so much! We lived in poverty; I didn’t know then what a bathroom was. Women had to go once in a month, after the menses, because a woman can sleep with a man provided that she passed through the mikveh.

But mom was going, they were frequenting the mikveh very regularly in those times, it was something normal. And when mammy was going, she took me and my sister too. I was the happiest. Married women had to undergo a certain ritual, they had to do this in the mikveh, and religious men too.

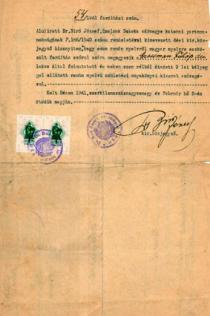

Religious men, who were engaged only in religion, went to the mikveh every morning, and they had to immerse three times. The rabbi too, before praying, he enters the mikveh three times. Before getting married, a girl has to go to the mikveh, otherwise they won’t issue the marriage certificate, and one can’t get married without that.

At the time [before my wedding] I strictly had to go to the mikveh too, though we already had an apartment with bathroom. [Editor’s note: Of course the essence of going to the mikveh is not the hygienic, but the ritual cleanness. The hygienic washing has to precede the ritual purification, but the former can’t substitute the latter. The ritual cleanliness can be obtained only where ‘natural’ waters meet.]

I went there, I set in the mikveh, I washed, I didn’t immerse, but when I came out, there was a woman, who had to comb me – I brought a comb –, she poured some water above my head, and she said something [a prayer].

Then I was in the mikveh here, in Des, because the husband of a girlfriend – she was called Fani Izsak – was the mechanic there, and she kept on inviting me: ‘Come, let’s go to the mikveh a little, you don’t have to pay anything.’ So we went there with the children.

Here in Des there was a large mikveh, there was a separate one for men, and one for women. Where the community’s office is, the mikveh was there [opposite to the synagogue]. Where they are selling bread today, that was the mikveh. But it was very nice, the cabins were made of timber, there were separate bathtubs [in each cabin], and there was a bench, a coat-rack, one could hang on their clothes, and the hot water was flowing, and one could take a good bath.

It was called the Jewish bath, Christians attended it too, everybody who didn’t have a bathroom bathed there. That was the bath. So that’s how it was back then. And it was very cheap. It was a smart thing, the mikveh, because people didn’t have the possibility to bath, and it maintained washing.

It is also a hygienic religious commandment. Because in fact the entire Jewish religion is based on hygiene. Alike kashrut is also a good thing. Later, when Jews left [emigrated from Des], the mikveh was closed. Approximately between 1960 and 1970 most of the Jews left 2.

So they closed it, because it had no reason to maintain it. But these smarty pants [the community leaders] sold it, they shouldn’t have sold the Jewish bath. The community sold everything; it doesn’t have any possessions yet, only the synagogue, the office and that yard, the rest is not ours anymore. Though it was such a large property…

I attended the Jewish school for four years, we had an ordinary Jewish [primary] school at the time, then I attended the Romanian school for three more years, but I learnt in Romanian [from beginning to end]. [Editor’s note: Starting from 1921 the Romanian educational laws prescribed that the teaching language of Israelite schools was Hebrew or Romanian.]

We had a Jewish school of four grades in the yard of the synagogue. We had a Romanian teacher – he wasn’t Jewish –, Crisan, he was teaching all the grades, four grades were together, boys, girls together. Sometimes we went to school in the morning, sometimes in the afternoon, it depended on what the teacher said. We didn’t learn much, if I think it over.

There was a very wealthy girl, she was a very good student. I don’t know if it was so because she was rich, or she was rich because they had brains. Perhaps she had her own teacher. She knew everything, absolutely everything.

We were learning limping, we didn’t learn too much. We had geography, we had history, mathematics, grammar. And nothing else. We didn’t have ‘limba romana’ [Editor’s note: Edit Grossmann says ‘limba romana’, meaning ‘Romanian language’, but she means literature.], only ‘gramatica’ [grammar]. But we learnt poems, they were in the book, we learnt poems, they still come to my mind often.

I attended the Jewish cheder as well from the age of seven. I forgot everything. I could read [Hebrew] well, and now I can’t. First a bocher was coming to our house. Well, he came to us regularly, dad was paying him. In those days there were a lot of poor Jews, and the bochers were given meals.

One came to us every Wednesday, he took lunch at our house, and mom gave him something for dinner and breakfast. They were teaching Hebrew alphabet and reading, nothing else. Then we were going to the cheder, to the ‘malamed’ [melamed]. That’s how they called the teacher, melamed, that was the Jewish teacher.

He was a nice old fellow, we went there separately, girls and boys. But he didn’t bother too much with girls, he taught girls only reading, they said ‘ivre’ [Ivrit]. We went to the cheder mainly during vacations, we went there three times in a week, but we were paying, the melamed had to be paid. We were sitting there and spending time, we set there the whole morning.

The melamed was speaking Yiddish, Hungarian, Romanian, but when he was sending us out, he said: ‘Gaje rajn!’, ‘Go out!’. Or ‘Gaje hajm!’, ‘Go home!’ During school year, when we left school, we had to go to the cheder a little, for about half-an-hour, to recite, to read a part from the book, to learn the letters.

The cheder was installed in the entrance hall of the synagogue, there were long tables and benches. Here in Des there was a separate cheder, a big cheder, not like in Nagyenyed.

I learnt tailoring, because daddy was a tailor too. We had a workshop, and dad said: ‘Why should you go somewhere else to learn, you will work here and you’ll get to know.’ And indeed, I learnt well tailoring. It’s not an easy craft, back then we worked with so heavy irons, an iron weighted ten kilos, it was made of pure cast-iron. That iron was very interesting.

We had an iron stove, we filled it with coal, and when the coal caught fire, we put in two or three irons. We had a long iron holder, we used that to take out the hot irons, we put on some four handles, and we scraped them off on the floor to make it clean. And we ironed with that.

Well, now I can feel my hands. And I worked there day and night. We had a workshop in Nagyenyed. And we earned our living quite well, so we didn’t make a fortune, but we made our living of that workshop. We had apprentices, we had work. [It was the apprentice’s task] to sweep out the workshop, to clean the machine, to bring coal, to take out the garbage, to bring home the clothes. And to learn the trade.

We always had two or three apprentices. They were Hungarian and Romanian boys: Gyuri, Dezso, Peter – the latter was Romanian, Petru, he was from Mokania. [Editor’s note: ‘Mokan’ – this word was used also for a mountain shepherd or for a Romanian from Transylvania.] Tailoring is very hard, I was the only girl apprentice.

We had a big Singer sewing machine in the workshop, and we had one more machine, but it wasn’t so good. And there were two tables for ironing, but they were so big, that one could open them, and the apprentice was sleeping there. It was like a big-big case. It still must be in Nagyenyed, I left it there. I slept in that table too for a long time.

Oh, one could sleep so well in that table! A straw mattress was put in it. When Russians came [during World War Two], I slept there. But I was sleeping there other times too, only in winter, because we didn’t have enough wood, and we heated only one room, my parents were sleeping in the two beds, and I was sleeping in the workshop, in that table. Because the workshop had to be heated anyway, we were working there.

I had suitors, but not so many, I didn’t have time for that. Formerly the custom was that they took us home, and we invited them in, they came in, they stayed until eight or nine in the evening, they knew they had to go home at that time. We didn’t have coffee, we offered them pastry and tea.

The Jewish young people of Nagyenyed too organized tea-parties. It was very nice, we danced a little with a phonograph, we danced tango. I was member to the Trumpledor [also called Betar] 3, this was a rightist Zionist organization. We came together, we learnt Hebrew songs, dances.

There was an esplanade too, but it wasn’t like in Maramarossziget. People used to say that the Jewish esplanade was in Maramarossziget. On Saturdays only Jews were promenading, there were so many Jews in Maramarossziget. But not in our town, we all were promenading.

But you shouldn’t think the promenade lasted for long! I was walking only on Sundays, because I was working. But on Sundays I went to walk as well. We started to promenade at five in the after-noon, on the main square, from one corner to the other, then we crossed to that side where the EMKE café was, and we went round like this.

This was the esplanade. Everybody dressed up nicely, we looked very nice. The fashion was very nice back then, we wore suits and coats fitted to the waist, I had such a coat too, it was black-grey, its pockets stuck out and it had a little black fur collar. It looked nice.

There were very beautiful Jewish girls in Nagyenyed, especially nice ones, but there was a Hungarian girl, Ildiko Ungvari, she was so beautiful that everybody stopped and looked at her. I can still picture her. She was rich too, and she was elegant. She was so beautiful! I don’t know what became of her. And rich and poor people didn’t walk separately. Everybody was promenading, there was no exception, with their suitor or friends.

I was promenading with a Hungarian boy a lot of time, with Gyula Kiraly, he was my suitor for a while. He visited us as well, we had a very good relationship with his entire family too, with his parents as well. Then, when the handing over occurred [the Second Vienna Dictate] 4, he came over here, in Hungary [Northern Transylvania], I think he went to Zilah.

He escaped, to be more precisely. He was even imprisoned, but he escaped again, he succeeded in it, and passed over. There he met a girl from Marosujvar [in Romanian: Ocna Mures], she also passed over, and he got married. However the family wouldn’t have agreed by any means that I married him. Such thing didn’t exist.

There weren’t mixed marriages at all in those days. A Jewish girl didn’t marry a Christian. Her husband could have been old, or like this or that, but the man must have been Jewish. After the war this changed, it occurred that Jewish boys married Christian girls.

- During the war

Before the war started, and before they took us to Gyulafehervar, we had a proper little workshop in Nagyenyed. There was a hotel and a restaurant next to our workshop, and in 1940, when the Germans came in, they were lodged there. And there was a German soldier among them, who was a tailor – Oh, may God preserve him in good health, if he still is alive.

He was from Hamburg. He was such a good boy! He was very handsome, a nice, tall, brown man. He used to come to our workshop to work. Dad spoke German well. We didn’t trumpet abroad that we were Jews, but he must have known it. I think he might have known we were Jews, because the shochet used to come to our workshop, and the shochet wore a caftan, he had payes too.

He could see this. But he never spoke ill. He was such an honest German, a tailor. I could understand quite well what the German was saying. He didn’t really like the army, as far as I noticed, he felt very good when he came to our workshop, he felt at ease. He was happy there. He was in the workshop in the morning already.

At noon he left to take lunch, then he brought in something to repair or I don’t know what, he finished that, but when he had nothing to do, he asked dad work, and he helped us in tailoring. He ironed the clothes. He was ironing the whole day. He was a very-very upright person. We were very attached to him.

He was at us for about four weeks, he came in daily. And he brought fat in a pot for the apprentices in the workshop, they were very lucky, they ate bread with fat all the time. He brought some sugar, he brought buttons, he brought what he could.

But he brought us boots, a pair of boots, a sole, I don’t know what else, and we had to give, to surrender these as Jews to the Romanian state, boots, sole, I don’t know what, and the German brought us all these. And at night, when dad was going home, he always put something under dad’s arm-hole.

We helped him too: we bought him what he needed, he prepared the package he was sending to his wife at us. Dad bought in his place – he didn’t want to –, as if dad needed it, two fox collars, and we [girls] bought him three pairs of silk stockings to his wife, and I don’t know what else.

And we prepared the package in the workshop, in the evening, and we post it under dad’s name. I suppose he wasn’t allowed [to send packages], because he asked dad to send it. That boy was a good person, a real human. I always remember him, that there were honest Germans too, one couldn’t lump together everybody. German, that doesn’t mean that each of them is anti-Semite, and they all want to kill the Jew.

We were very sorry when he left. When he left, we got scared. One day some five officers entered. Dad said softly: ‘Now they are going to take us away, it’s all over.’ He tells me: ‘Edit, you should go out.’ I didn’t go out.

One of the German officers says to me [looking at me]: ‘Dein Tochter?’ Is this your daughter? Dad says, yes. He replies: ‘You have a nice daughter.’ I was sixteen or seventeen years old [Editor’s note: Edit Grossmann was born in 1922], of course a girl is lovely at the age of seventeen.

‘What will happen now?’ – dad whispered to the boys. Only I and dad were Jews. The others [the apprentices] were Christians, Hungarians, Romanians. Gyula, one of the aids says: ‘Don’t worry, Mister Grosz, it will turn out all right.’

The German officer takes out a notebook, and asks dad: ‘How much do I pay? I want to pay you for the Schneider, the tailor was here and occupied your workshop.’ Dad says: ‘I don’t need any money.’ The German officer says: ‘This can’t be, I must write here that I paid you.’

And he gave some money for the rent, for the Schneider took up a part of the workshop, and worked for the army. Well, and he paid us. When he left, we thought we would collapse of fear. Because dad was so scared, he was deadly pale

We were afraid, of course we were, because we already knew [what was going on]. For example once a big German company [of officers] came in our workshop, I don’t what they needed, one wanted his coat to be ironed, the other wanted a button sewed on, and the name-board was put out, [with the name] Grosz, they thought we were Germans.

And one of them said that he had come from Warsaw, and there, in Warsaw Jews were so dirty, and they were in ghettos, and he showed hundreds of pictures to dad. Of course dad was afraid, because he said: ‘God forbid the same happening to us.’

We were afraid, and many offences were committed. In Nagyenyed too there were legionaries 5, they had dark-green shirts and black trousers. They had a headquarters – they called it ‘szediu’ [‘sediu’ – headquarters in Romanian] –, and they were going on the streets singing each day, they were marching, singing these Romanian songs.

What was it… ‘nici o palma [de pamant] romaneasca nu se da inapoi...’ [‘we won’t give back not even a patch of Romanian land’], they were singing such songs. They didn’t hurt us, we even had legionary client. We had a small axe, since we had wood-fired heating then, poor dad always put the axe to the entrance, he said: ‘If somebody wants to come in, I will hit him with the axe.’

Mammy always used to tell me: ‘Edit, put aside the axe so that your father doesn’t notice.’ I say: ‘I won’t. Leave it there! If somebody comes in, let him slap that person.’ Yet nobody ever entered our house. But for example they took the rabbi into the forest, and beat him awfully.

Though he was a very poor, honest man. It was winter, it was snow, and a Romanian man came to collect wood, saw him lying in the snow, put him on the cart, and brought him home. He knew him. There were very rich Jews as well in Nagyenyed, not everybody was poor.

There was Berkovits, then Benyovits, they were merchants, and they had vineyards, they had woods, they were wealthy. The legionaries pushed in the behind of Benyovits an inflator, and they pumped him up with that, so he died soon after. And they beat Berkovits so hard that he died too.

They beat my uncle, Gyula Grosz too, because he talked very much, he upbraided the legionaries, he was arguing with them, and they took him away, and beat him hollow with a nightstick. In Balazsfalva people, Jews were thrown out the windows. There some Orthodox priests were big legionaries. There was a huge legionary nest in Balazsfalva. In Nagyenyed too.

And so help me God I’m telling the truth, the sons of honest people became legionaries. With who we were in good terms, there weren’t any problems before the war. There was no such thing that you are Jewish, and you are Hungarian. Particularly in Nagyenyed, Hungarians had such a good relationship with Romanians, with Jews, as if they were brothers.

There wasn’t anything ever, we were on good terms. And this war came, this Hitler story, and drew the whole world crazy. And the dogma of a person like Hitler comes, and fills people with evil. He built it in their heads indeed. Because there were such people really, one couldn’t even believe that they could hate Jews.

Previously we were great friends, and one day anti-Semitism comes. And we had to go through this. There was a very honest Romanian family in Nagyenyed, I don’t remember their name. All the boys became legionaries. But everybody was so astonished that why they became legionaries, they had frequented Jewish societies, they had courted Jewish girls before. Nobody would have thought that they would become legionaries.

In those times [when Northern-Transylvania got under the rule of Hungary] 4 there was a mass migration. The Romanians came here from Kolozsvar, from the occupied territories [Editor’s note: to Romania; the Second Vienna Dictate didn’t refer to Nagyenyed situated in South-Transylvania], and Hungarians went from here to Hungary [Northern-Transylvania] 6.

The great legionaries derived from Romanians, the arrow-cross men from Hungarians. The youth inhaled this hate emanated by Hitler, it is an extremely week organ, not everybody can resist the evil. And so many became legionaries, and so many became arrow-cross men in Hungary.

One day they took daddy – I was eighteen years old – to Fehervolgy [Editor’s note: in Romanian Albac, 105 km to the west from Torda] to cut trees, he was there for eight months. So it was me who worked in the workshop, I was struggling to support the family, to pay the taxes etc. So I had my own big problems, big difficulties, and I worked a lot.

Then daddy came home, he came home ill, they let him go home [because he fell sick]. He came home in 1941, just one week before the Russian-German war started [Editor’s note: on 22nd June 1941 Germany attacked the Soviet Union].

Then they moved us to Gyulafehervar [29 km far from Nagyenyed]. First people from Marosujvar [the Jewish families living in Marosujvar] arrived in Nagyenyed, they arrived on a Monday, and they stayed for one week in Nagyenyed. When in 1941 the Jews from Marosujvar came to Nagyenyed, it was so interesting, that a widow came to us as well with her three daughters, I don’t know what their name was, I didn’t know them before.

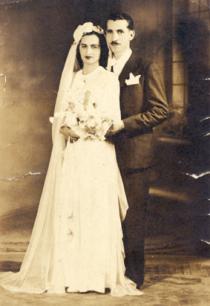

They arrived on a Thursday, they installed themselves in our house on a Friday, and this Hersi Jakabovits came to visit them. He saw my sister, and fell in love with her at once. And in 1943 the wedding took place.

Then in June 1941 we all had to go from Nagyenyed to Gyulafehervar, people from Marosujvar, from Tovis and Nagyenyed too at a quick pace 7. We went there freely [unescorted], but we had to leave the town in two days. The Militia-man came to each Jewish house, and told that starting from this and this time we would be forbidden to be in the town, and we had to go to Gyulafehervar.

It was a difficult situation, it was just me who didn’t take it to heart, because I was young, I couldn’t comprehend [what was going on]. The elderly people lived it through differently, but the young… we’ll manage it somehow. We hired a cart, and we left by a horsed carriage.

We brought with us a bed, the eiderdown, the pillows, the blankets, the carpets, what went into the carriage, not so many things. We went together with my grandmother, Babi and with Zali, we hired one carriage for us, and one for them. But we didn’t stay together in Gyulafehervar, because we didn’t find accommodation.

They [grandmother and Zali] lived on a loft. But I went ahead with my sister, we found a car. There was a cheder in the yard of the Jewish school in Gyulafehervar, and we were sleeping there, the entire family for one week. But it’s interesting that the German soldiers were there too, in the same yard, they had their lodgings there.

In Gyulafehervar there was a large Jewish school, and a part of it was reserved, the German soldiers were lodged there. Mammy was very much afraid: ‘Don’t go out! You mustn’t go out!’ But we went out, we came back, they didn’t say a word. They didn’t speak to us at all.

They didn’t do any harm ever. Germans didn’t do anything wrong to Jews in Romania. Whoever says Germans behaved badly with Jews in Romania, that person is lying. Once a German was running after me, I was returning from the workshop late, and he was taken with me. I ran down straightly to the cave, and I locked the door. I got so scared of him.

In Gyulafehervar there wasn’t any ghetto, we lived in the town, but we weren’t allowed to leave Gyulafehervar. Everybody got installed where they could, at Jewish families, not at Christians. But finding a place was very difficult; there weren’t as many accommodation possibilities as many Jews arrived.

We weren’t lucky, and we got only a bathroom, we put in the bed, mom and dad slept in the bed, we, me and my sister on the floor. But we were sleeping so badly, then winter came, and it was very bad, we didn’t have any heating. And later we rented from somebody a little room-and-kitchen with great difficulty.

Dad was sewing for somebody, and he had some sort of hall, and we made there a very small room and one more room for kitchen, and we moved there. My sister worked too, she was doing manicure, and I was working throughout, so we supported our parents.

At the beginning I went here and there to work, where I found work. There wasn’t any tailor’s workshop, it was summer, it wasn’t season, but I worked at a Swabian, he was called Rehan, he was a very upright person, he had a tailor’s workshop.

It was forbidden to go out in the street after eight in the evening, and people could go to the market in the morning only after ten. It was forbidden to go out until ten in the morning and after eight in the evening. In Gyulafehervar the mayor was very decent, if he saw somebody, he didn’t care.

And there was a shop, which gave bread to the Jewry, he [the mayor] told [the baker] to give Jews meal and bread. There wasn’t enough bread during the war, people suffered the most from the lack of bread. There wasn’t sugar at all. I worked at Rehan, his workshop was in a Catholic school. And once a Catholic bishop came in.

In Gyulafehervar Catholics behaved very nicely with Jews. They were so straight, that in summer they gave the catholic school to the Jewry, they could sleep there, and there was a place where they could cook, with the Primus of course. And the bishop came in, and said to Rehan, to my master: ‘Who’s this little girl?’ I was young. ‘A little Jewish girl – he says – from Nagyenyed, and she’s working at my place, she learnt tailoring, but she’s good.

She can make trousers, she can make everything.’ Some nuns were escorting the bishop, he made a sign to one of the nuns, and she brought me a little pot with sugar. I went home, where we stayed, I was running: ‘Mom, look what I got!’ We didn’t have any sugar, one couldn’t even see sugar! There was a candy store, well sometimes we entered the store, but sugar at home…

Mom says: ‘Edit, did you kiss the bishop’s hand?’ I said no. ‘You should have kissed it – she told me –, that’s the custom.’ [Editor’s note: At that time Aron Marton was the Catholic bishop in Gyulafehervar.] I didn’t know this. So we had something to put next to the tea in the morning. We drank tea without sugar before.

Mammy procured sugar-beet, she boiled it, and we put that. Can you see now what war is like? But we strictly observed religion. There was a shochet, everything. In Gyulafehervar they made a kosher hash-house, one could go there with the bowl, they gave noodles with cabbage, bean-soup. But dad didn’t let mom go. He said, we won’t get there, to go with the bowl or pot, like a beggar. As far as we can buy and make for ourselves, he said, we have to support ourselves.

In Gyulafehervar we had to wear yellow stars 8. I didn’t make one as I should have to [in a star’s shape]. Some did, some just stuck on a yellow rag or ribbon. When we came back to Nagyenyed, we kept on putting it on, we didn’t take it down from every coat, sometimes we put it on, sometimes we didn’t.

We came home in Nagyenyed on 7th or 17th January 1942. I came ahead with my uncle [Gyula Grosz] to find an apartment. My uncle found a small room for my grandmother somewhere very far and a small room for himself. First they lived together, then he moved alone.

I quarreled, I fought so much [with the owners], until I got back [also for a rent] a room where we lived, in the yard of the bank. Because in fact we left there all our things: there was the bedroom, there were two armchairs, there was a kitchen cupboard, a whatnot, where the dishes for milk and for meat had stood separately. We didn’t find anything there when we came back.

In Nagyenyed it was very difficult to buy bread. They gave ten decagrams to a Jew. But there was a man called Onak, well he gave some bread sometimes in secret. He bribed the policeman – as there was always a policeman –, he gave him to drink, because he had a bodega too, and he gave bread to Jews.

He was very-very nice. But in Nagyenyed either we couldn’t go out after seven or eight. We did, but stealthily. I always worked in the workshop until twelve in the evening, and I went home. Poor mammy, she always hid [somewhere in the house]. And the headquarters of the legionaries was right in the yard of the workshop where I worked. And I was such a brave girl, I wasn’t afraid, somehow I just couldn’t believe there was so much evil in people, I couldn’t imagine this.

Then the legionaries were down on their luck. They were in danger yet, they wanted to take over the power in Romania, but then they were caught and put in prison. The legionaries sat in prison until the end of the war.

[Editor’s note: The Iron Guard was the para-military terror organization of the legionaries. The Iron Guard was an extreme-rightist political organization between 1930 and 1941, which propagated nationalist, mystical and anti-Semite ideas; many acts of terror and political murders were due to it, respectively many anti-Semite actions.

Though it was banned several times during the 1930s, in 1940 it participated at the forming of the government, since Ion Antonescu, assigned by the king as Prime Minister with full powers formed the government with the Iron Guard.

However the two periods – the one determined by the Iron Guard and the Antonescu-regime – overlapped only between 1940 and 1941, since Antonescu dissolved definitively the party following the unsuccessful attempted coup organized by the Iron Guard in 1941.

The Antonescu-regime lasted until August 1944, when Romania changed sides. The notorious anti-Jewish pogroms and deportations, still handled as taboos by the Romanian historiography, are linked to this period, to the name of Antonescu.]

And the communists too [were in prison]. There is a huge prison in Nagyenyed, a lot of legionaries were there, and they were beaten so hard, that they were shouting so loud, the whole town could hear their howling. And after this, when the war was over, the communists put the rich in prison, they were beaten too. Well... that’s how it always goes. First the legionaries and the communists got beaten, then communists were beating capitalists.

In 1943 my sister got married – since she got married during the war, dad was very annoyed with her. There were a lot of quarrels, dad didn’t quite support her getting married, he said that during war one shouldn’t get married. Mom said: ‘Let it be, if she wants to, let her get married.’ It was a love match.

The husband of my sister was from Marosujvar [Editor’s note: Marosujvar, in Romanian Ocna Mures lays 24 km far from Torda to the south]. His parents had a bakery in Marosujvar – those days it was called Uioara –, they baked challah on Fridays – on Friday we, Jews bake the braided bread for Sabbath, we call it ‘kajlics’ [Editor’s note: the local name for challah].