SUZI SARHON

Istanbul

Turkey

Interviewer: Yusuf Sarhon

Date of interview: January 2005

Suzi Sarhon is a very kind-hearted 78-year-old housewife who is always ready with a smile. She has devoted her whole life to looking after her family, children and grandchildren, always supporting them in their hour of need both physically and psychologically. She is a very active woman but her activities have been cutailed in the last few years because of her heart problems. Suzi Sarhon can get along with practically anyone, as she is sincere, affectionate and understanding. That is why she is liked by everyone she meets. She lives in a flat at an apartment building in Gayrettepe with her husband. She spends certain days of the week meeting her friends to play cards and chat.

My family background

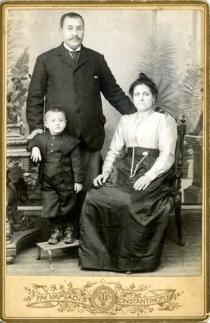

My father’s father, Avram Danon, was from a very good family. They were 3 siblings but I do not know anything about them. I do not know what my grandfather did for a living. He was a well-educated and talkative person. He was quite tall apparently. He had died a long time before I was born so I do not have much information about that side of the family except that they were very religious. As I never met my father’s father, I do not really know how he used to dress. I was told that they were quite well-off and that they used to speak French and Ladino.

My father’s mother, Sultana Danon had 4 siblings but I do not know their names. This grandmother died of cholera. I do not know when and where, but apparently there was a kind of epidemic and she died. My grandfather then remarried (I do not remember the name of his second wife) and had another son called Beno Danon.

My father’s side of the family was from Istanbul. I do not know exactly where they lived, but it might have been in Ortakoy because my father was from Ortakoy [a district where Jews used to live on the European side of the Bosphorus].

My mother’s side of the family had all come to Istanbul from Salonica. The whole family on that side was from Salonica. I know that they arrived in 1910, but I do not know why they moved here. I do not have much information about them except that they were very religious, just like my father’s side of the family.

My mother’s father, Hayim Benmayor, (I do not know his birth or death dates) was a very nice man. He was from the best of families. When I say “the best of families” I mean “rich and educated”. They were quite a big family. He had two other siblings about whom I know nothing. Hayim Benmayor studied in Salonica because he was born there. He was a well-educated man and quite talkative. He was tall and dressed very fashionably in clothes that were the highest fashion of the time. I do not know what he did for a living. My mother’s side of the family spoke French and Greek because they had all been born and raised in Salonica. They all spoke Greek perfectly.

I never got to know my mother’s mother, Sara Benmayor (nee Faraci). She was a sick woman. She had a very high degree of diabetes and went blind consequently. She had 3 more siblings but I do not know anything about them. My grandmother used to wear long-sleeved dresses of her time. She used to wear jewelry and had a “kolana” [Ladino term for “long gold chain”] which laterbecame my mother’s. She would wear her jewelry when she went out to go somewhere; not that they would go on outings very often. They had a lot of family, cousins, sisters, brothers, and they would gather in one another’s homes. One other thing I remember about grandmother Benmayor is her going into a depression after her son Jak Benmayor went to the USA to settle there. She died when she was 52-53 years old.

When my mother’s father, Hayim Benmayor came from Salonica they settled in Bakirkoy [an old Jewish district on the European side of Istanbul]. My mother and her brothers, Avram, Mishel, Jak and Daniel all grew up there. When my grandfather came from Salonica, he bought 4 houses there.

The houses had wells in their gardens. There was no tap water then and they used to get their water with a pump from the wells. According to what my mother told me, they had two maids in their home, so I guess they were quite well-off.

My mother’s side of the family was quite religious. They practised all the Jewish traditions. They bought kosher meat for example. Then when Pesah [Pesach] came, they would change all the kitchenware. They did all this for a very long time. They used to go to the synagogue every Friday. The Jewish religious holidays were celebrated at home. When they lived in Bakirkoy, my grandfather was the president of the synagogue there.

My mother’s family had very good relations with their neighbours. The neighbours were Jewish, too. There were a lot of Jews in Bakirkoy. They used to call this district “Makrikoy”. The Greeks who lived there used to say that “Makrikoy” meant “little village”. The name later changed into “Bakirkoy”.

My mother and her brothers grew up in Bakirkoy, then the years went by. My eldest uncle, Alber Benmayor went to Germany on business and he lived there for years. Then some years after my grandmother had died, my grandfather went to live with his son in Germany. My uncle bought a beautiful house in Germany, a house with 6 floors. He was in the razor blade business. He had a factory. My uncle, Alber Benmayor, (I don’t know his birth date) died in Istanbul in 1951. He was married to Lidya Benmayor and had a son, Mario Benmayor. Mario was born in Germany in 1929 and came to Turkey when he was 8 years old. Here he studied at a British school [probably English High School for Boys]. 1 We did not use to frequent them. His father had a textile business in Mahmutpasha [a business district in the Euopean side of Istanbul]. When my uncle died, Mario took over the business but he was not successful and quit. Then I remember he went into the automobile spare parts industry. He married a Christian German girl here, and had 2 sons but I don’t have any more information as we did not use to see them. I think Mario died recently.

During the holidays, they gathered within the family and would visit each other in their homes. There were a lot of cousins, big families on both sides.

My father Jozef Danon, I don’t know his date of birth, was born in Istanbul. My Dad was a very good man, and he did a lot of good deeds for people. His sister, Viktorya Danon (I don’t know her birth and death dates) married Rober Schilton and went to live in Bursa. A few years later, they returned to Istanbul. I do not have much information about her. I just know that she was older than my father and that my father sent them sacks full of food because their economic situation was not very good. My father looked after both our family and hers. He was always doing good to people in need. He exhausted himself trying to help people. He was also a member of one of the charity organizations of the Jewish community, called “Sedaka u marpe” [charity and healing]. He used to take a lot of things there, like hats. I distinctly remember him taking them hats, I don’t know why or what they were doing with those hats but hats it was. He worked very hard for this organization of the community and tried very hard to help.

My father was a very talkative person. He was skillful and hardworking. I remember, when we went to my uncle’s (my mother’s brother) for the New Year celebrations, it was my father who prepared the table and organized the food etc...

On Sundays my father would set the table beautifully and he would make us all coffee with milk and call us to the table. He would do all that so my mother would not get tired; not because she was ill or anything, just because he loved her so. He would prepare everything and then he would say: “Come on Tutuni, the table is ready”. My father called my mother “Tutuni” instead of “Fortune”.

My father had a hardware shop. He was the only one then; there were no other hardware shops around. He used to do a lot of business with Anatolia and his business was very good. We were very well-off. I grew up with a nanny and we had a maid, too. Unfortunately my dad died in January 1936. I was 9 at the time. He had a heart disease. In fact, when he and my mother got married, he already had heart problems. He was not very young when he got married. I used to see him feel uncomfortable and open the window to get some fresh air. He would breathe deeply to relieve his distress. “What’s the matter, Jozef?”, my mother would ask him at those times and he would reply, “Oh, nothing, it’s nothing”. He wouldn’t tell her anything. He just exhausted himself running around for other people. One day he had a heart attack. The doctor warned him: “Mr. Danon, you will not bend down to even tie your shoes, let your children tie your shoes. Don’t tire yourself and don’t go out”. But in the meantime my father’s business was not going well because he used to gamble with his friends and neighbors every night till morning. He ruined his business in that way. He and my mother would have fights about this gambling of his. He would even go to neighbors in our apartment and not come back for hours on end. In that way, the shop and the business was ruined. When he died, he had a lot of money owed to him because he had sold a lot of goods to a lot of people but we did not know anything about the business and how were we to find those people? So we couldn’t collect any of those debts. No one came forward and said anything. He had a lot of clients in Anatolia and they all disappeared. If we, the children, had been older, then we could have followed and dealt with these problems but we were all so very young and we did not have anything.

My father had 5 siblings: 2 brothers, Izidor, Sami; and 2 sisters, Viktorya and Sara from my grandfather’s first wife and another brother, Beno, from my grandfather’s second wife. Beno still lives.

Izidor left Turkey (I don’t know when or why) and went to settle in the USA. He married someone there and had a child but we never had a lot of information on him. After long years, he came here once to see us. Apparently he had a hotel, a gambling hotel, in Las Vegas. He had one son only.

When Viktorya Danon got married, she became a Schilton. Her husband’s name was Rober Schilton. Rober was of Italian nationality and he came from Bursa. They got married in Bursa, then they came to Istanbul and lived in Tunel [a popular neighborhood in which the Jews lived]. When I was a little girl, I used to go to my aunt’s a lot. I liked Rober Schilton very much. He used to work at an insurance firm. Their economic situation was not very good but he was a very good man. They had 4 children: 2 girls, Sara and Suzi; and 2 boys, Alber and Sami.

My father’s other sister, Sara Danon married another of the Schiltons but I do not remember his name. She married a brother of Rober Schilton’s. They lived in Paris and had 3 children, with the same names: Alber, Sami, Suzi.

I do not remember anything about the other brother, Sami.

I do not know when the last brother, Beno was born. He grew up and got married and had a son, Albert Danon. He lives in Istanbul, in Sisli. I do not have any other information about him.

We mostly visited my aunt Viktorya with my mum and dad. I would see Beno there when he came for the holidays to visit my aunt.

My mother, Fortune Danon, (I don’t know when she was born), was born in Salonica. She came to Istanbul when she was 13. My mother was a quiet person, she did not speak too much. She spoke Greek very well and French, too. She had studied in Greek in Salonica. Then here, she studied in French, I don’t know which schools, maybe there was a French school in Bakirkoy. Her French was very excellent. She was very intelligent.

She was not a very authoritarian mother. She raised us all with great economic difficulties after my father died. After being really well-off with maids and nannies, it was douby difficult for her to raise 4 children. She did it all on her own. My uncles also helped of course, moneywise. My grandfather (mother’s father) had 4 houses in Bakirkoy, 4 houses for each of his 4 children. When my grandfather went to Germany to live with his son, he rented out those houses. When my father died, my grandfather was no longer alive. My mother had 2 brothers in Germany and they immediately wrote to her and said: “we do not want our share of the rents of the houses”. The brother who was living here said the same thing and they made it possible for my mother and us to live on these rents. She would go to Bakirkoy every month to collect the rents, and the tenants would sometimes give her the money and sometimes not. My uncles in Germany would send her money from abroad, too until Hitler came. When Hitler came, they came back here. I do not remember exactly when they came back but it must have been a little before the war.

My mother had 4 brothers: Alber, Mishel, Jak and Dani (Daniel), all of them born in Salonica. Two of them, Mishel and Alber Benmayor lived in Germany until Hitler came.

Alber Benmayor had gone to Germany when he was 16. He studied there, then he started a business. He opened a razor blade factory there. Then when he came back he lived very close to our house in Kurtulus. Here he opened a jersey cloth factory. He was quite well-off. He had a son, Maryo Benmayor. Maryo was 8 when they came to Turkey. Here he studied at the English High School 1 and then at Robert College 2. I do not know what he did after that. My uncle Alber died here in Istanbul in 1950.

Mishel was also born in Salonica of course, like all the others. I do not know when, but he also went to Germany when he was very young both to study and then to do business. He was in business with his older brother Alber and then came back here when Hitler came. After the war was over, he went to Paris. There he married a woman whose surname was Behar and whose first husband had been killed by the Germans. He went in to the textile business in Paris. He died in Paris, but I do not know when.

My other uncle, Jak Benmayor got married here and then went to Los Angeles with his wife. I do not remember when he went or who his wife was. We were told he had 2 daughters.

My fourth uncle, Daniel lived in Istanbul and married an Italian girl called Emilia Kilkus. They did not have any children. He was in business with her father. I think they had a hardware shop. Later on, when the business did not go well, he took his share and left. He bought two flats with that money and lived on the rent of those flats. He did not work. Daniel died in 1957.

Both my father and my mother studied in French. In those times, most people studied in French. My parents’ mother tongue was Ladino, they learned Turkish later on but they could never speak it like we did. My father was alittle better but my mother spoke very little Turkish. She spoke Greek, French and Ladino. My parents spoke Ladino with each other.

My parents met through a matchmaker but I do not know the details. They never told me anything about it. Just that the matchmaker proposed my mother as a very eligible young woman of very good family. Then they got married, I do not know when or where. They probably got married at the synagogue, I don’t know. After the wedding they lived at a house opposite Pera Palas [a very old and famous hotel in Tepebasi, very close to the Grand Rabbinate in the European side of Istanbul]. My father’s business was in Tahtakale [a business district in the European side of Istanbul].

My father always wore suits and his shoes had laces always. They were some kind of boots with laces. He also wore a hat called “republique”. [top hat] But before that, the men used to wear the fes 3 before Ataturk 4 and his reforms 5. My mother had kept my father’s fes, with which he used to go out.

My mother used to read a lot. That is why there used to be a lot of books in our home. She used to read books in French, all sorts of books. After my father died, she started reading books about diseases. She got obsessed with illnesses, heart diseases, other diseases. She would read these all day long and would not go out.

Growing up

I was born in the house opposite Pera Palas, but then they moved to a house in Tunel. I was too young to remember when. When you went into that house, there were 3 rooms downstairs, you went up a flight of stairs and there were 2 more rooms and then you went up again and it was the attic. It was a beautiful house but quite tiring. We had a big stove downstairs and another one upstairs. We used to sit upstairs, near the stove and watch the people coming and going in and out of the underground, and others getting on and off the tramway, because Tunel was the last stop. We used to entertain ourselves watching all these people.

We did not have a garden. We could not have a pet because my mother did not like pets and would never permit such a thing.

I remember my father bringing home some fruit like dates. I can’t remember its name now. He brought those and then hung them. My brothers and I would go and pick the fruit before it was done. They weren’t dates but some yellow fruit. They would hang them and then they would dry and we would eat them. When they were done they got red. We would eat them before they got red. My father would hang them at a place that got a lot of sunshine. I thought they were called “ziruelikas” [a Ladino word meaning “plums”] but they weren’t.

My mother used to do the shopping. She would go to the open market to do her shopping. There would be sellers who came to the door of course, but she preferred to go to the open market. Sometimes she would take me and my brothers, too and we would carry everything back.

My parents were religious but not fanatical. They did all the Jewish holidays and never did anything on Saturdays. On Saturdays, we would either sit down and read books or go and visit my aunt. They were careful with kasherut. They did not go to the synagogue every Friday; just on the holidays or when somebody got married or for funerals. My mother also had the “loksa”. She had these beautiful special kitchenware for Pesah [Pesach]. When Pesah was over, these would be put into a special chest used only to keep the “loksa”. Then when my father died my mother did not have the will to go to all this trouble and she left all this.

Neither my mum nor my dad were members of any political party or any social or cultural organization. Just my father worked as a volunteer at the charity.

My family had Jewish neighbors now and again. There were a lot of Jews in Tunel. When I was 5 or 6 we moved to Osmanbey [a district in the European side of Istanbul]. Thre were Jews there, too. We had Jewish neighbors there, too. My father used to go and play cards with them. There were 2 Jewish families at that apartment. One family was called Behar, the other I don’t remember. They all used to play together, either at their homes or at ours, but more often than not they would go and play outside, where I don’t know. My mother did not go because she did not know how to play cards.

My parents are buried in the Jewish cemetery in Ulus [a district in the European side of Istanbul]. They were buried with a religious ceremony. And of course there was a rabbi and a hazan [chazzan] at the funeral. The sons of the family sang the Kadish and I always do their “meldado” [yahrzeit] every year.

I had 3 brothers, 2 older than me and one younger.

My brother Alber was born in Istanbul in 1917. He had meningitis when he was 5. One day he was visiting our grandmother (my mother’s mother). He was jumping on the cushions and then he hit his head on something. My grandmother put him to sleep and he slept till morning. When he woke up, he couldn’t speak. My Dad took him to the doctor, and the doctor said: “you will not tire this child; he will start to speak very slowly”. After a couple of years, we had a cousin in Tunel, Viktorya Danon, my father asked her: “Please, let Albertiko come to you for a while, you have cats”. So Alber went to stay with her for a while and indeed he started to speak there. He did not go to school. There were teachers who came to the house to teach him French. He would beat the teachers, he was sick really. He actually started to speak when he was 10. What a pity, because when he was little he was one of the smartest kids ever. Now, the doctors tell us not to put a child to sleep if he takes a fall or hits his head etc... But my grandmother did not know that. When my grandfather came home that night she even told him: “Please, Hayim, do not make any noise, Albertiko took a fall” and she had him sleep till morning. And he got meningitis. But later on, he grew up and he even did his military service for 2 years. Then, when my uncle came back from Germany and opened his jersey factory, he took Alber to the factory where he worked until my uncle died in 1951. Then he went to work for the Kastro family as an office boy and retired from that job. Then when my mother died, we took him to the Old People’s Home 6 in Haskoy. He lived there for 10 years, then took a fall and died in 1999.

Vitali was born in Istanbul in 1922. He studied primary school and the secondary school until my father died. He was 14 when my father died, and had to start working. He worked for a florist in Osmanbey near our home, and brought home some money. He would take flowers to clients. Later on he worked at a big shop in Beyoglu [very famous district, otherwise called “Pera”, in the European side of Istanbul], called “Galeri Kristal” as salesman. They sold glassware and crystalware there. When he was 14, Vitali met an Armenian girl called Adirne Donaloglu, who lived in Ferikoy [a district between Osmanbey and Kurtulus, where a lot of non-Muslims, especially Armenians used to and still live]. They fell in love and later got married. The families did not want this marriage of course but while Vitali was doing his military service, he came on leave once and they got married secretly, by civil marriage only of course. The families did not know but I did because Adirne was my friend. They had two daughters, Linda and Rita. Linda was born in 1949 and Rita in 1954. They studied in state schools. Linda married an Armenian, Simon Kokyan and she became Armenian, which means she became a Christian. They had two daughters as well, Karolin and Karin. Rita, on the other hand, married a Moslem boy, Emin Kaplan and she converted and became a Moslem. They had a son called Akin. Vitali died in Istanbul in 1982. His wife, Adirne, died many years before him, I don’t remember exactly when.

My third brother Sami was 1.5 years younger than me. We grew up together and we were in the same school. After he finished primary school, my mother sent him to Saint Michel [a French Catholic high school in Osmanbey]. I do not know why, but he did not finish St. Michel. Then he started working and later he opened a perfume shop with a partner. Then he got married. He married Fortune Algazi. They had two children, a girl, Sara and a boy Yasef. Sara was born in Istanbul in 1956. I do not know where she studied but she got married in her early twenties. Then after 18 years of marriage, she got divorced. She never had any children. Yasef was born in Istanbul in 1962. He also got married and then divorced. He has a daughter. My brother Sami always worked in the same job. Then he had heart problems and then one day, one Friday in 1989, he was coming home from Sirkeci [a business district in the european side of Istanbul] in a taxi and he had a heart attack and died in the taxi. The following day was the Bar-Mitzvah of my grandson, Izel and we were preparing for that. It was a terrible time for me. On the one side I was grieving for my brother and on the other side there was the happiness of the Bar-Mitzvah of my only grandson. It was a terrible clash of emotions. On the Saturday night, we celebrated the Bar-Mitzvah among the family members but it was entirely spoiled for me.

None of my brothers are alive today.

My parents were going to have another sibling actually. When we were living in Tunel, I was 5 at the time, my mother got sick. She got the flu and was coughing terribly. We had a Jewish maid and she gave her the wrong medicine. Instead of the cough syrup the doctor had given her, she gave her an enema to drink! She did not realize it was the wrong medicine and my mother was 8 months pregnant at the time. The medicine killed the baby inside her. My mother screamed for 3 days and 3 nights. There were no gynaecologists then. My father called the midwife. The midwife said the child had died inside anyway and then she made my mother give birth like a normal birth. They pressed on her tummy and made her give birth. She was in such a lot of pain. I cannot forget her screams for days after that. If the baby had lived, she would have been 5 years younger than me. They were going to name her after my mother’s mother, too. She died because of the maid’s mistake. In spite of this, the maid continued to come and work for us.

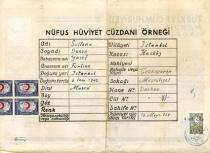

I was born in an apartment building called “Gul Apartimani” [Rose Building] opposite Pera Palas, in Tepebasi in 1927. My mother kept a record of all the births. At that time people could get their identity cards whenever they wanted, not like now, that you have to leave the hospital with a birth record paper. Then, children were born, and after a while they would go and get their identity card. I got my sister’s identity card. I had a sister who was born before me in 1925. She was born on 7th July. She died when she was 13 or 14 months old from some sort of illness. My mother told me she had died when she herself had been one month pregnant to me. Then when I was born, they gave me that other one’s identty card but my mother recorded my birth in one of her books: “Suzi. Elle est née 24 janvier 1927” [in French: “Suzi: Born on 24th January 1927”]. There was no need to get another identity card. No one checked anyway. Her name had been “Sultana”, so I got that name as well.

We moved to Tunel from Tepebasi when I was very young. We lived on the top floor of an apartment building. We had both electricity and tap water as far as I remember. I also remember the tram. There were trams on the roads but I do not remember any cars. The roads were asphalted then. There were big stones. No cars.

There were a lot of Jews in Tunel then but we did not have much contact with them because our family was quite extensive and we usually met with them. The Jews would usually gather in Sishane [very near the Galata Tower]. They used to speak in Ladino in the streets. There were fisherman, street sellers etc... who would shout in Ladino in the streets. There were people of every trade; hat makers, shoemakers etc... My father had a cousin, Viktorya Danon, who had a big shop (I don’t know where) where she sold and repaired paintings.

My mother raised me. At first I had both my Mum and my Dad. I had a governess and a maid. The governess would teach us French, had us play games and taught us poetry. The governess would teach and the maid would do the cleaning and the housework, that’s how it was then. The governess was Jewish and she left in the evening. We used to sleep with the maid.

We had all the Jewish traditions in our home when we were kids. Kipur, Roshashana [Rosh Hashanah] were great celebrations in our home.

There was a synagogue in Tunel then, before coming to the Neve-Shalom synagogue. [It was opened in 1923 in the location of the previous Apollon cinema. Although it was officially called the Knesset Synagogue people kept on refering to it as the Apollon synagogue.] It does not exist any more. [it was completely burned down in a fire in 1941] I don’t remember what it was called. Well, haham, hazzan, shohet, they all existed then. When my sister was stillborn, my father went to the synagogue to have a rooster sacrificed, in case something else terrible happened to the family.

The day we liked best was Roshashana [Rosh Hashashanah]. It was the new year and my mother bought us new clothes and we would wear our new clothes. We had new and clean shoes and we would all dress up. We would have a very good breakfast that morning and we knew it was Roshashana [Rosh Hashanah]. There would be a lot of guests. My mother’s cousins would come, my aunt (my father’s sister) would come to visit. Or we would go and visit them. We were a big family.

Apart from Yom Kippur and Roshashana, we also celebrated Pesah [Pesach] and “beraha las frutas” [Ladino term for Sukkoth]. My mother would do a lot of cleaning before the holidays. We even painted the house before Pesah. Even I did some painting in the house before Pesah.

When I was a young girl, a friend of mine and I would go to the Sisli Synagogue 7 at Yom Kippur. We would go near the time it would be finished. We went to see who was at the synagogue. We went up to the women’s place and watched the people. I don’t remember my friend’s name, but she lived near us and we would go to the synagogue on foot of course. We rarely took the tram. Not if we could walk.

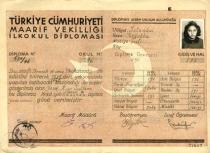

My father first sent us to some sort of preschool. The law that said we had to study at a Turkish primary school 8 had not started yet. So Vitali and I went to St. Benoit for a couple of years. There were nuns at this school and I had a round cap. Then the law was passed and I went to the state school called “44. Ilkokul” [44th Primary School] in Bomonti [a district very near Osmanbey]. There weren’t many private schools then. All my brothers and I studied in that school. Of my classes, I liked Turkish best of all. We also had history, geography and citizenship classes. It was inetersting because we would learn about all the things that Ataturk had done. The I went to the “Arts and Crafts School” where I learned sewing and household management.

There was a teacher I did not like in primary school. Why didn’t I like her? Well, it was like this: in our school they used to give lunch to the poor kids. One day, there were chick peas for lunch. I asked for some and they gave me a plate but I saw some stones in the food. I told my friend: “the people here are very dirty”. She immediately went and told this to the teacher whose name was Nahide. “Sultana said this about you”. So the teacher called me and asked me what the problem was. I said it was nothing but from that day on she disliked me. We would go out into the garden and if anything fell or was dirtied she called me to pick things up or cleans things up. Then when we were in fifth grade, we had finishing exams [to get primary school diploma]. This teacher asked me the most difficult questions so she could flunk me but my own teacher did not let her do that. He protected me and I passed.

We had music and gym classes, too but no language classes. I did not feel any antisemitism on the part of my teacher or my friends. There were very few Jews in that school, most of them were Turks. I had some very good friends among them. I remember one girl called Remziye for example.

What I most remember of those days were the military parades, special national days and independence days [Turkish Independence Day]. 9 We would go to Taksim square on 29th October or 23rd April [The Turkish National Assembly and Children’s Day] 10 to see the parades. I had even memorized the marches.

The most colorful memory I have of my childhood was having seen Ataturk himself in the flesh. I saw him in Florya [a sea side resort on the European side]. My uncle Daniel used to take me to the beach in Florya. As my uncle and his wife did not have any children, they loved me very much. And my mother, as the kids were very naughty, would say, “please come and get Suzi” and I woıuld go to my uncle’s. His wife would dress me in beautiful clothes and I would stay with them. In the summer, they would take me to florya to swim. We used to hire a cabin and spend the day swimming. Ataturk had a house in Florya then and we would see him. One day, when I was 7, we saw him walking on the beach. He was dressed beautifully. He had a little girl with him, I think it was his adopted daughter, Ulku. She was very sweet. I used to see her there, too. Anyway, I went to him and gave him my hand. He shook my hand and said “my dear child”. This was quite a memory.

I had many greek friends outside school. We were very very good friends. After Osmanbey, we moved to a house in Kurtulus when my father died. My uncle wanted us to live close to him. I continued to go to the same primary school because there were no schools in Kurtulus then. We used to walk from Kurtulus to Bomonti [a ten-minute walk]. I had wonderful friends in Kurtulus and I learned to speak Greek perfectly from them. We often went to each other’s homes. I remember one of my friends’ parents had a pharmacy and we would go to the pharmacy to help when they were open one night every week. The pharmacy was close to our home.

My best friends were Greek. There was Zorka, for example. They lived in my uncle’s apartment. There was a big vacant lot at the end of the Kurtulus Street where we played ball, jumped ropes and had a good time. The Greeks were so lively, we would often hear music coming from the hand organ. After we finished our homework, we would go out together or play with dolls at home. One of my friends had a piano and we would go to her house to listen to her playing the piano. They were rich, that’s why she had a piano.

I have many meories from the times I spent at my uncle’s home. For example, I remember that my uncle’s wife’s brother, Atilyo Kilkus and his wife (I can’t remember her name now) had had a baby. The name of the baby was Romano. There were 10 years’ difference between us. So when I went to stay with my uncle I would play with little Romano. The 14 months later Covani was born. They lived in my uncle’s apartment, too. So I was with them all the time I stayed at my uncle’s and I stayed with them a lot. They used to call me “Suzika”. They loved me very much. Romano and Covani Kilkus were of Italian nationality. Romano Kilkus was born in 1937 and Covani Kilkus in 1938. Both of them studied primary school in the French Catholic school called “St. Esprit”, then they went on to St. Michel for secondary and high school. [French Catholic School] Romano worked for a Jewish businessman and Covani was in household appliances spare parts business. Neither of them is alive today.

Another nice memory from Kurtulus is my friendship with the famous singer Ayten Alpman [Turkish jazz singer]. We met through a fried who introduced us and we became friends. I was 15 at the time. We went out together and she used to sing. We used to go to each other’s homes a lot.

Apart from this, we didn’t usually eat at restaurants when we went out but there used to be a cafeteria called “Hay-Layf” [High Life] beside the Tan Cinema in Pangalti [a district very close to Osmanbey and Kurtulus on the European side of Istanbul]; and my brother and I used to eat cakes there. We liked that place a lot and we went there a lot.

When we wanted to go to a place we usually took the tram. There were trams in Kurtulus. We got on trains a lot as well when we went to Florya with my uncle. Apart from these I do not really remember there being any cars. My uncles did not have cars. The first time I got into a car was when I got into my husband’s car in 1949.

During the War

During the Second World War, we used to cover our window panes with dark blue blinds. The alarms went on when night came and everyone would go into their houses and cover the windows and nobody would go out. No light could be seen from the outside because the blinds we put were very dark. We were also asked to turn the lights really down so no light could come out. In those days, they sold everything with certificates. My poor brother Alber would get into long queues to buy bread, margarine, sugar etc...

We heard what was done to the Jews in Europe afterwards. During the Holocaust in Europe we did not notice any rise in antisemitism here in Turkey. When my uncle Michel came back from Germany, he told us about the terrible treatment of the Jews in germany. As he was of Turkish nationality, they did not do anything to him. The Turkish consul told him: “you had better leave as soon as possible; I will give you a passport as you are of Turkish nationality and you must get away immediately”. My uncle came back in 1938, just before the war started.

During the war, the Wealth Tax 11 did not affect me or my family. We did not have any shops or anything. Uncle Michel was taxed but I don’t know how much. He had a shop in Eminonu [a business district in Istanbul] then. No one else from my family was taxed. But of course, a lot of people were taxed quite alot of money. My uncle Daniel was called for the 20 military classes. 12 They took him but none of the others.

After the War

I remember the 6-7 September 1955 events. 13 That day, my elder son Sami was at his grandmother’s (my husband’s mother). My husband had gone to pick him up. By the time they came home, the streets were full of looters and people attacking shops and houses. I remember them coming home terribly frightened. Our landlord was Greek then. It was an apartment building of two storeys. The landlord and his family lived upstairs. They came down to us, terribly frightened. Also there were two Greek grocers at the corner of our street. When there was a shortage of sugar or coffee these would not sell anyone these goods. So now, that day, the angry mob came to these shops and threw all their coffee and sugar into the streets shouting: “Hey, Kocho, no coffee eh?!” The poor men hid in the basements of their shops. Kurtulus was in a terrible state. We stayed at home quite afraid. Then it stopped. Everywhere was ruined. After that all the Greeks in Istanbul started to run away, to Greece most of them.

Then I remember this policy of “Citizen, speak Turkish”. We actually needed to speak Turkish. 14 They used to call us “Jews”. For example, when we walked in the streets, they used to say: “Don’t speak in ‘the jewish language’, speak Turkish”. [The word for Ladino in Turkish was for long years “yahudice”, meaning “language of the Jews”]. Then, when we studied the primary school in Turkish, we were able to speak in Turkish after that.

When we lived in Osmanbey, there was a “donme” 15 family from Salonica, who lived above us. They were “Selanikli”s [from Salonica: meaning donmes] but they converted to Islam and became Turkish. They spoke Ladino very well. My mother knew them well but I don’t remember their names. I only remember that they and my mother used to speak in Ladino.

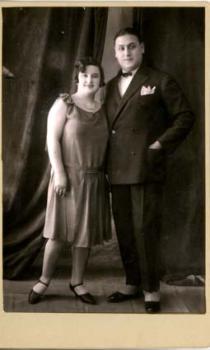

My husband, Izak Sarhon, was born in Ortakoy, in 1914. His mother tongue is Ladino and he speaks French, too. My in-laws were very nice people. I met my husband through an acquaintance. That person told us there was somebody (my husband) so and so and when we said “OK”, we met at the Hay-Layf café in Pangalti. My uncle and my brother Vitali came, too. We saw each other for the first time there. We chatted a little, then we ate something and then he left. Then, the person who introduced us went to talk to his father and they said “OK”. Then his father called my uncle and they talked about what was necessary to talk about [probably about the dowry], and then they said “OK”. Then Izak came to visit us one evening and then we got engaged in 1948. We got engaged in my home. My uncles, my in-laws, and my sister-in-law all came to my home and we had a family dinner. There were a lot of flowers. My in-laws brought me a ring. And my family gave my fiancée a gold watch as a present. Of course, the fact that my fiancée was Jewish was an important factor in our decision for marriage.

In 1949, one week before the wedding, we had our civil marriage ceremony in Tunel . The civil marriage was at the registrar’s hall and it was quite crowded. I wore a tailor-made suit and my husband wore a dark suit. My witness was my uncle Daniel and my husband’s witness was a cousin of his mother’s, the lawyer Selim Danon. After the ceremony we went to my father-in-law’s house and there was a kind of cocktail. There were about 30-40 people present. We talked and listened to music on the radio, there was nothing else in those days.

One week later, on a Sunday, on 10th July, I got married at the Zulfaris Synagogue 16 in Karakoy at 6:00 p.m. I don’t know why we got married so late in the day, probably because there was no other free hour. I bought my wedding dress from a shop, I did not have it made especially for me. On that Sunday morning, we got up early. My uncle and his wife, my friends, all came to my house. The hairdresser also came and did everybody’s hair. Then we got dressed. At 10 minutes to 6 we went to the synagogue all together. My cousin Sami Schilton gave me away and he and my mother got on the “teva” with me. I also had a little bridesmaid and an older one who accompanied Sami Schilton later on. After the wedding ceremony, we went to my husband’s parents’ house. We changed there and then went to the Belvu Hotel [the turkish version of the french expression “Belle Vue”]. We did not have a party that night. We stayed at that hotel for 4 days. It was raining hard all the time so we spent the whole of the 4 days inside the hotel. We did not go out. Then we went to Caddebostan [this district on the Asian coast of Istanbul used to be a summer resort. It is now a residential area.]. We rented a house for the summer. Our friends also rented a house and we spent the whole summer together having fun.

When I got married, my husband was in the import-export business. He had a place in Karakoy [a business district in the european side of Istanbul]. The business did not go well, so after a while my husband started working at the shop of my cousin Alex Samuel. This was a cloth business and my husband was a clerk there.

We had 2 sons. The first, Sami, was born in 1951; and the second, Yusuf, was born in 1958. Both were born in Istanbul.

When they were young, we used to speak French with our children. However, when they reached the age of 6, we started speaking Turkish with them. They were going to go to a turkish school so we did not want them to have problems at school with the language. At that time we spoke only French in the family and that’s the language they heard, not Turkish. So then we had to revert to Turkish when their time to go to school came.

We had a Greek neighbor who lived below us at the apartment building we lived in and they had a daughter the same age as my son Sami. They used to play together and Sami had even learned how to speak Greek from them. I used to take the kids everywhere, to the cinema, the theatre everywhere, with other children and their mothers of course.

Every summer we went to Caddebosta for the summer. There we would hire a boat and go swimming with the kids. When we came back, we went back home in a horse carriage. We had a lot of friends. I can give you their names as far as I remember: Ceni Jak Rutli, Esti Mordo Peres, Zelda Yomtov Behar, İzi Süzet Levi. They were very intimate friends. We were a big group and during the day we went swimming together. Then in the evening we would meet again with the kids. The children would play together, we would prepare food and eat all together. Sometimes we would go out. My husband had a car and we would go for rides. We were together with our friends every weekend. And when summer came, we would all rent houses near one another so we could be together all the time, both during the week and at weekends. During the day we would go swimming and in the evening we would either go to the cinema or gather at one house.

When the children grew up a little, we sent them to the Mahaziketora. [Talmud Tora] In summer, they would go to the Mahaziketora in Caddebostan, and in winter they would go to the one in Sisli. We wanted them mto learn about their religion, especially before their bar mitzvahs. After the lessons, there were quite a lot of activities at the Mahaziketora, like games and dancing. They would stay for those activities as well. Then both my sons went to the Jewish youth clubs. Sami was a member of the “Kardeslik” [“brotherhood”] club in Kurtulus, and Yusuf was a member of the Dostluk [friendship] club in Osmanbey.

We raised our children according to the Jewish traditions. They knew all the holidays and they started fasting at Yom Kippur when they were very young. I used to take them to the synagogue whenever it was festival time, so that they could see and learn. At Simhat Tora for example, they used to take the Sefer Tora’s out, and there were alot of songs, and I would take my sons so they could watch all this.

My father-in-law was very religious. We went to their home whenever there was a holiday and we kept all the traditions. On Shabat, we did the “hamotsi”, drank wine, did the prayers, and at Pesah we read the Agada two nights. All this was celebrated at my father-in-law’s house.

We celebrated Sami’s bar mitzva both at the synagogue and at home. He made a speech both at the synagogue and at home. It was a beautiful bar mitzva. There were 90 guests in our home afterwards. We had a big house. We had musical instruments, and a big feast with waiters. Sami had an accordeon teacher who brought all sorts of instruments, especially percussion instruments. We had a lot of fun with those instruments.

My younger son, Yusuf, did not want to have a lot of fuss. So he had his “tefillin” ceremony on a Thursday morning and then we came home. Again there were waiters and a lot of sweets and cakes for the guests, but he did not want to make a speech or have another ceremony on the Saturday morning at the synagogue. So we just had the Thursday morning ceremony for him.

I learned how to cook from my mother and my friends. There are certain very traditional Sephardic dishes that I like making very much. The one I like best is “tomatoes filled with cheese”. I used to cook those and they would like it at home. Then we would make tomatoes again, this time filled with meat and cooked with a lot of sugar. Also we have “almodrote de berendjena” [baked aubergines]. You take the aubergines, boil and peel and then squeeze them. Then you add white cheese, “kasher” cheese [Turkish name for kosher yellow cheese, popular among both, Jews and non-Jews], a little bread, a little flour and an egg. You mix all this and put it in an oven dish and bake it. Then we have “bulemas”. You take the “fila” dough, put cheese in long strips of the fila, then roll the strips into rose shaped “bulemas”. You put them all on an oven tray, put grated cheese and egg yolk on them and then bake them. Then there are the “bumuelos” for Pesah. To make bumuelos, we soaked 3-4 matzot, then squeeze the water out. We add one egg for each matza and a little salt. We mix all this and then fry little balls of it in the special bumuelo pan. They can be eaten with powdered sugar afterwards.

We had Jewish friends in Kurtulus and we saw them frequently. During the week we used to play cards. The husbands played poker and the wives played “relance” [a card game where the aim is to make sequences of at least three cards and finish the cards in your hand]. All our friends were Jewish. They were all very good people of good families. We also used to go to the cinema or theatre as a group as well. When summer came we would often go to Buyukdere [a district on the Bosphorus, near the Black Sea] and swim. I would say we had a “medium” social life.

My elder son, Sami, finished his secondary school at “Tarhan Koleji” [a private Turkish school founded in 1959 by Turkish statesman and educator Mumtaz Tarhan] in 1967. He then went to Israel to study high school there. It was fashionable those days; everyone was sending their kids to Israel to study. Sami also wanted to go, so we sent him and he left with a few of his friends. He went to study electronics there. He studied for one year but he was not happy because they taught him not electronics but carpentry. So after a year, he came back. He finished the lycée at Tarhan Koleji. Then later, he was able to get into university and he studied economics at the Iktisadi Ticari Ilimler Akademisi [Economics Academy in Osmanbey].

My sons grew up, they became young men, they had friends, they came they went. My elder son, Sami married Ceni Levi in 1974. In 1976 they had a son called Izel. Izel studied in the Jewish High School 17. He did not go on to university. He did his military service and since he came back he has been working in the textile business.

In 1980, my elder son had a daughter called Sandy. She finished “Kadikoy Kiz Lisesi” [private Turkish high school on the Asian side of Istanbul]. Then she studied tourism and hotel management at the University of Istanbul. She has been working at the Swiss Hotel since she graduated.

My younger son Yusuf studied at the Saint Benoit [French Catholic high school] school. He also started studying Economics at Istanbul University 18 but he couldn’t finish it because there was a lot of terrorism at the universities at that time 19. So he went to do his military service. In 1992, he married Karen Gerson and in 1996 they had a daughter called Selin. Selin studies at a private primary school where she learns both turkish and english.

The foundation of the state of Israel had made us very happy. I remember being very happy that morning when we heard the news and nothing else. We never thought of doing our aliya there because we were content here. Of course we had friends and family who went and settled in Israel. My husband’s aunt, Fani Saranga for example was one of the first to go and settle in Israel with her family.

We do not have too many relations with the jewish community today; what I mean is, we are not members of any club or organization. We try to follow our religious traditions and go to the synagogue at weddings, funerals, bar mitzvas and less frequently during the holidays.

Our children are not as religious as we used to be, nor have they raised their kids in the traditional way, but we have not had any conflicts about this with them. We did not interfere. Today, it is our children who gather the family and do family dinners. We are tired and can’t do it any more.

We still meet with friends once a week. I meet with my women friends: Jinet Behar, Zelda Matalon, Hayat Kubilay, Suzet Molinas, Margo Arditi and Zelda Behar. We have been seeing each other for the last 20 years and we still go on. We used to see each other outside the card playing days too but we can only meet once a week nowadays. My husband also meets his friends for poker once a week. When we come together as couples, the men play poker and the women play bridge. That is all really.

We used to go on holidays until 3 years ago. We went to places like Marmaris [a seaside resort on the Aegean], Ayvalik and Sarmisakli [seaside resorts on the Marmara]. We haven’t been able to go for the last 3 years because basically there is no one to go together with.

In the 1986 Neve-Shalom massacre we were at home and heard the news on TV 20. We felt terrible and were extremely sad of course.

We got terribly upset when we heard the 2003 bombings, too 21. We heard that on TV too. We were really scared.

When we are alone with my husband we speak Ladino; with our friends we speak both Turkish and Ladino, but with our children we speak Turkish only.

Glossary

1 English High School Boys

Founded in 1905 in the district of the Galata Tower by the British Consulate, primarely to provide comprehensive education for the children of the British colony in Istanbul. In 1911, Sultan Mehmet V gave the British Embassy a 5-storeyed wooden building in Nisantasi for exclusively schooling purposes. The school gained the status of high school in 1951 and also became coeducational. In 1979 it was nationalized and renamed as Nisantasi Anatolian Lycee.2 Robert College: The oldest and most prestigeous English language school in Istanbul, since the mid 19th Century providing education to the elite of Turkey as well as other countries in the region. Robert College, was born in 1863 in the village of Bebek by the Bosphorus, when Christopher Robert approached Cyrus Hamlin with his desires and found a receptive audience. Hamlin, an American schoolmaster, had been running a school, a bakery and a laundry in Bebek at the time. Robert was a wealthy American industrialist desiring to establish in Turkey a modern university along American lines with instruction in English. These two men, an educator and a philanthropist, successfully collaborated to found Robert College.Until 1971, it included two campuses: the actual Robert College exclusively for boys and the American College for Girls. In 1971, the American College for Girls and the Robert College boys school united and co-education started under the name of Robert College at the previous American College for Girls campus. On the same date, the Turkish government took over the boys campus, which became Bogazici University (Bosphorus University). Robert College and today’s Bogazici University were and still are the best schools in Turkey. Through the years, these schools have had graduates in the top positions in Turkey’s business, political, academic and art sectors.

3 Fez

Ottoman headgear. As a part of the Imperial Prescript of Gulhane (a westernizational campaign) of Sultan Mahmud II (1839-1876) the traditional Ottoman dressing code was abolished in 1839. The fez, resembling the hat of the Europeans at the time, was introduced and was widely used by the Ottoman population, regardless of religious affiliation, afterwards. In the Turkish Republic it was considered backward and was outlawed in 1925 by the Head Law. In the Balkan countries fez was regarded an Ottoman (Turkish) symbol and was dropped after gaining independence.4 Ataturk, Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938)

Great Turkish statesman, the founder of modern Turkey. Mustafa Kemal was born in Salonika; he adapted the name Ataturk (father of the Turks) when he introduced surnames in Turkey. He joined the liberal Young Turk movement, aiming at turning the Ottoman Empire into a modern Turkish nation state and also participated in the Young Turk Revolt (1908). He fought in the Second Balkan War (1913) and World War I. After the Ottoman capitulation to the Entente, Mustafa Kemal Pasha organized the Turkish Nationalist Party (1919) and set up a new government in Ankara to rival Sultan Mohammed VI, who had been forced to sign the treaty of Sevres (1920), according to which Turkey would loose the Arab and Kurdish provinces, Armenia, and the whole of European Turkey with Istanbul and the Aegean littoral to Greece. He was able to regain much of the lost provinces and expelled the Greeks from Anatolia. He abolished the Sultanate and attained international recognition for the Turkish Republic at the Lausanne Treaty (1923). Under his presidency Turkey became a constitutional state (1924), universal male suffrage was introduced, state and church were divided and he also introduced the Latin script.5 Reforms in the Turkish Republic

After the establishment of the Turkish Republic (29th October 1923) Kemal Ataturk and the new Turkish government engaged themselves in great modernization efforts. Fundamental political, social, legal, educational and cultural reforms were introduced in the 1920s and 30s in order to bring Turkish society closer to the West and shape the republican polity. Ataturk had abolished the Sultanate earlier (1922); in 1924 he did so with the Caliphate (religious leadership). He closed down the dervish lodges, the turbes (tombs of worshipped holy people) and forbade the wearing of traditional religious costumes outside ceremonies. According to the Hat Law the traditional Ottoman fes was outlawed; surnames were introduced and the traditional nicknames were outlawed too. International measurement (metric system) as well as the Gregorian calendar was introduced alongside female suffrage. The republic was created as a secular state; religion and state were divided: the Shariah (Islamic law) courts were abolished and a new secular court was introduced. A new educational law was created; the institutes of Turkish History Foundation and Language Research Foundation were opened as well as the University of Istanbul. In order to foster literacy the old Arabic scrip was replaced with Latin letters.6 Old People’s Home in Haskoy

Known as ‚Moshav Zekinim‘ in Hebrew and ‘Ihtiyarlara Yardim Dernegi’ (Organization to Help the Old) in Turkish. It was opened in 1972 by the initiation of the Ashkenazi leadership in the building formerly housed an Alliance Israelite Universelle school and a rabinical seminary. Some 65 elderly members of the Jewish community currently reside in the home.7 Sisli Beth-Israel Synagogue

Founded in the 1920s by restoring the garage of a thread factory. The first weddings took place in the early 1940s. In the 1950s, with the demographic movements of the Jewish populations from Galata towards the Sisli area, the need to have a larger synagogue became prominent. Two architects, Aram Deregobyan and Jak Pardo designed the project. The new enlarged synagogue started its services in 1952.8 Law of Primary Education

As a part of the Reforms in the Turkish republic the ‚Law of Education‘ was passed in 1931, according to which compulsory primary education in Turkish was introduced, and consequently all non-Turkish primary schools were outlawed. The Alliance Israelite Universelle schools were closed and all other foreign schools started their education only after 5th grade, after primary school in Turkey.9 Turkish Independence Day

The Turkish Republic was founded on 29 October 1923. Every year 29 October is celebrated as the Turkish Independence Day. There are military parades, student parades, concerts, exhibitions and balls. 29 October is also a national holiday.10 National Sovereignty and Children's Day

National day in Turkey. Kemal Ataturk dedicated April 23, the Sovereignty Day to the future generation. It was on this day in 1920 that, during the War of Independence, that the Grand National Assembly met in Ankara and laid down the foundations of a new, independent, secular, and modern republic from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. Ever since "Sovereignty and Children's Day" is celebrated annually. It is celebrated at each school by performances and the children‘s representatives replace state officials and high ranking bureaucrats in their offices. On this day, the children also replace the parliamentarians in the Grand National Assembly and hold a special session to discuss matters concerning children's issues.11 Wealth Tax

Introduced in December 1942 by the Grand National Assembly in a desperate effort to resolve depressed economic conditions caused by wartime mobilization measures against a possible German influx to Turkey via the occupied Greece. It was administered in such a way to bear most heavily on urban merchants, many of who were Christians and Jews. Those who lacked the financial liquidity had to sell everything or declare bankruptcy and even work on government projects in order to pay their debts, in the process losing most or all of their properties. Those unable to pay were subjected to deportation to labor camps until their obligations were paid off.

12 The 20 military reserve classes: In May 1941 non-Muslims aged 26-45 were called to military service. Some of them had just come back from their military service but were told to report for duty again. Great chaos occurred, as the Turkish officials took men from the streets and from their jobs and sent them to military camps. This was done in case the non-Muslims allied themselves with the enemies in case Turkey entered the war. They were used in road building for a year and disbanded in July 1942.

13 RICHARD

PLEASE KEEP THIS ENTRY FOR THE GLOSSARY EXACTLY AS IT IS. THE ITEM YOU SENT ME IN THE 03 FILE HAS GRAVE MISTAKES AND DOES NOT MAKE SENSE.Dear Karen, please pont out where zou find the mistakes in the rewritten glossarz and I will look into this. Please understand thai it is also important to keep glossaries as short as possible and straight to the point. the entrz on this pogrom is not to explain the historz of forced assimilation in turkey, mazbe we can write one on that too when it comes up, neither would we want to mention nothing about the armenian issues (in line with our agreement).

First of all the date has been entered wrong!!! It is not 1925 but 1955, so basically we want to mention political events that led to that date not get stuck in the 1920s. Karen

I would suggest you identifzing the ‚grave mistakes‘ in the shortened and edited entry and I will correct them. Please understand that glossaries are especially sensitive issues as they are the ‚objective‘ part of our work, therefore have to be as objective and also compact as possible. I am looking forward to the suggestions. Thanks a lot.

The 6th – 7th September 1955 events: The basic policy of the first years of the Turkish Republic was to “turkify” all its citizens, demanding that they have a common history, culture and language. The government knew that this was not easy to do with the non-muslim citizens. With the events in 1915 with the Armenians, and the population exchange (Greeks with Turks) in 1924, there were barely any non-muslims left in Anatolia. The government then turned its eye towards Istanbul, which hosted a large number of non-muslims, especially Greeks. In the minority report written by the government, it was suggested that Istanbul be cleansed of all Greeks. The catalyst in realizing this aim came with the problems that arose in Cyprus. On 6th September, Istanbul awoke to the news in the papers about Ataturk’s house being bombed in Salonica. This was not true, but the rumour became the spark that lit the rioting, looting and rape that followed. It was later realized that most Greek houses and businesses had been marked beforehand. Of course, other non-muslims got their share of the looting and destruction, too in the general frenzy. All in all the result was: 3 people dead; 30 wounded; 1004 houses, 4348 shops, 27 pharmacies and laboratories, 21 factories, 110 restaurants and cafés, 73 churches, 26 schools, 5 sports clubs and 2 cemeteries were destroyed; 200 Greek women were raped. A great wave of immigration occurred after these events and Istanbul was cleansed of its Greek population.

14 RICHARD

I HAVE REWRITTEN THIS ENTRY SO PLEASE CHANGE IT IN THE FINAL FILE. THE CHANGES YOU MADE DID NOT EXPLAIN THE SITUATION CLEARLY.Dear Karen, part of my job is to edit glossaries and make sure they are compact, short but contain all important information and written in an objective way, if possible in line with contemporary english language historiography. I do edit glossaries from all countries (holding an MA in Balkan History I have some insight to the isses I think). If you feel I am putting something wrong please let me know I promise I will make all necessary changes but I can not leave glossaries unedited as this is a part of my work as editor.

I would prefere you pointing out with all those glossaries zou do not agree with the problematic points and I promise, I will look into them and make changes in the next update, but I can not see putting unedited entries on the new update. Can you do that with both problematic ones and send them to me in a separate file? Thanks.

Citizen, speak Turkish policy: In the years 1930’s – 1940’s, the rise of Turkish nationalism had the Turkification of the minorities as its goal. The community that was mainly aimed however, were the Jews, with whom the Turks did not have a history of enmity. The Salonican Jew Moise Cohen (1883-1961), who had been in close touch with the Young Turks in his home town in the years preceding the restoration of the Constitution, took the old turkish name Tekinalp and led a campaign among his fellow Jews to encourage them to speak only Turkish to integrate them fully into Turkish life declaring that “Turkey is your home, so you should speak Turkish”. In the major culture however, the policy of “Citizen, speak Turkish” was seen as pressure put on minorities to speak Turkish in public places. There was no law to enforce this but it was more of a social pressure to make sure everyone learned how to speak the language of the new country. There was a lot of criticism and verbal attacks and jeers on those who did not comply with this social rule.

15 Donme

Crypto Jews in Turkey. They are the descendants of those Jews who, following the example of Shabbatai Tzvi (leader of the major false messianic movement in the 17th century), converted to Islam. They never integrated fully into the Muslim society though and preserved various distinctions: they married between each other, performed services in distinct mosques and buried their dead in separate cemeteries. Up until the Greek annexation of Southern Macedonia (1912, First Balkan War) they lived in Salonika and were relocated to Ottoman territory (mainly to Istanbul) with most of the rest of the Muslim population later.16 Zulfaris Synagogue/Museum of Turkish Jews

Located in the previous Zulf-u arus street (meaning Bride’s Long Lock, today the street is called Perchemli Sokak which means Fringe Street) This synagogue, recorded in the Chief Rabbinate archives as Kal Kadosh Galata, is commonly known as Zulfaris Synagogue. The word is derived from the former name of the street in which it is located: Zulf-u arus, which means Bride’s Long Lock. Today the street is called Perchemli Sokak which means Fringe Street. There is evidence that this synagogue preexisted in 1671, when Haim Kamhi was Chief Rabbi, as the foundations date from the early 15th century Genovese period. However, the actual building was re-erected over its original foundation, presumably in the early 19th century. In the 1890’s, repair work was carried out with the financial assistance of the Camondo family and in 1904 restoration work was conducted by the Jewish community of Galata, presided over by Jak Bey de Leon. (source: www.muze500.com)

17 The Jewish High School: In the 1920s/1930s, the Jewish community supported Beyoglu Jewish Lycée was opened by the Bnai Brith in 1911 and taken over by Ashkenazi leader David Marcus in 1915 to replace the Alliance schools which had been closed by the French government because of the war. Turkish was the language of instruction. Hebrew studies were de-emphasized as a result of the 1932 law which forbade religious instruction in all Turkish schools. The Beyoglu Jewish Lycée, which was located in Sishane near the Galata Tower is now located in its new location in Ulus [near the Jewish cemeteryin the modern part of Istanbul] and has taken the name “Ulus Ozel Musevi Lisesi”, meaning “Private Ulus Jewish Lycée”.

18 Istanbul University

The University of Istanbul is one of the oldest universities in Europe (founded in 1453), and the oldest in Turkey. It was modernised by Kemal Atatürk in 1933. It has sixteen faculties on five campuses, the main campus being in Istanbul. It has a teaching staff of 2,000 professors and associates and 4,000 assistants and younger staff, and 60,000 undergraduate and 8,000 postgraduate students. Its graduates form the main source of academic staff for the Turkish university system, as well as providing a very large number of Turkish bureaucrats, professionals, and business people.19 Terror at Turkish universities: In the period of 1975-1980 extreme tension arose between the so-called leftist and rightist fraction of the student body. The fight was about whether or not to make the Turkish Republic a religious Islamic state (leftist position) or preserve the secular nature (rightist position). There were further fights within the leftist fraction too, between the communists and socialists. University education turned into chaos already in 1975: instruction almost stopped, and many students were scared to attend classes, as there were a great number of murders. The only university that was able to continue with instruction was Bosphorus University, mainly because all of its student body was basically leftist. It took five years for the government to finally pacify the situation by a military coup in 1980.

20 1986 attack at the Neve-Shalom synagogue

In September, 1986, Arab terrorists staged a terrorist attack with guns and grenades on worshippers in the synagogue, killing 23. The Turkish government and people were outraged by the attack. The damage was repaired, except for several bullet holes in a seat-back, left as a reminder.21 2003 Bombing of the Istanbul Synagogues: On 15th November 2003 two suicide terrorist attacks occurred nearly simultaneously at the Sisli and Neve-Shalom synagogues. The terrorists drove vans loaded with explosives and detonated the bombs in front of the synagogues. It was Saturday morning and the synagogues were full for the services. Due to the strong security measures that had been taken, there were no casualties inside, however, 26 pedestrians on the street were killed; five of them were Jewish. The material loss was also terrible. The terrorists belonged to the Turkish branch of Al Qaida.