This is a picture of my daughter Halinka. At that time I was working and living in the Jewish Children’s Home in Cracow and she lived as one of the children in that home. Halinka is wearing a very pretty dress. We used to get parcels of clothing from American Jews.

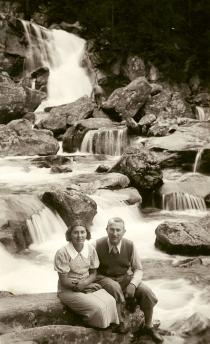

My first steps on arriving back in Cracow from the USSR after the war were to the Jewish Committee on Dluga Street [the Provincial Jewish Committee was set up in 1945 at 42 Dluga Street]. At the Committee I met Wiener, my cousin, and together we looked through the photo albums, and it was he who recognized them, I didn't recognize: 'Well look, this is your father and your mama.' I hadn't known my father without a beard. He hadn't known him either, but somehow he'd remembered better. The Germans had taken those photographs in the ghetto. It was a record of the people who had died. I don't know, Jews in general. They let me make copies. Before the war my parents had had nothing. Their rented apartment in Podgorze had been in the ghetto, and there was no question of my going in when I got back even just to take a keepsake from home. I tried. I wasn't let into the apartment and that was it. No, nobody opened up.

And then Mr. and Mrs. Kurtz, whom I’d met in Koz'modem'yansk, took me to the house of some relatives or friends of theirs because I had no place to stay. In the evening a few people came round - a few young men who had survived the war. One of them took me the next day to 6 Slowackiego Avenue and this is where I met Mala Rubinstein, who opened the first kindergarten for Jewish children in Cracow. The first. You see other than that, kindergartens were run by convents, by nuns, so Jewish children didn't go to them. Before the war she'd been in Germany somewhere, in some school for kindergarten teachers, and then later, together with some wealthy Jewess (Mala wasn't rich) she opened that kindergarten.

I spent one more night with those strangers, and then it turned out that Mala helped me to get my daughter into a children's home - because I didn't have anywhere to go - and found me a job in the same children's home. On Dluga Street. At the Jewish Committee there was this group of women that traveled round Poland specially looking for children like that [Jewish] - because there were people who'd taken children in simply out of pity. There was this one, Salus, came from Mazovia, but during the war he'd been in Ukraine with his father, his mother had perished somewhere, then the Russians had taken the father into the army, and the boy had gone along with the regiment because he'd had nowhere to go. And Mrs. Marianska, the chair of the Jewish Committee, had taken him in off the streets in Cracow. There were these two sisters, too, Paulina and Dora, who'd originally had a father, the father had lived somewhere outside Cracow, because he'd had a job with some horses. Then he died and they'd been left alone. Salus and those two sisters were the first 3 children in the children's home. Unfortunately there were only a few rooms there on Dluga Street.

Soon we got a whole 4-story building, where the Jewish Children's Home was opened. Cracow, 1 Augustianska Boczna Street [now 6. Chmielowskiego Street; the building houses Care and Educational Complex No. 2]. That was the address. The house had been built before the war [1936-1938, commissioned by the Jewish community organization in Kazimierz] as an old people's home, but there were no old people left, because they'd been murdered by the Germans. Then it had been a barracks, and apparently a brothel for the German officers. The back of that house butted up more or less against the Jewish hospital on Skawinska Street through the courtyards. And that's almost right on the Vistula [River]. It was a beautiful building, very decently fitted out, just damaged. It was equipped for our needs - there were washrooms, and a washbasin in every room. Bathrooms in the corridors. Luckily, in spite of the damage we were able to move the children in straight away. Because it had been a barracks, there were these army beds there. The painters went in; there was broken glass everywhere, window panes had to be put in..., as you'd expect after a war. The children helped to clear up, because 80 or more than 80 children arrived from the Soviet Union. A very large group, a whole carriageful came. There were boys and girls. More girls, of course. Jewish children. All Jewish. What 80 children meant?! All different ages! Some of them were so wild.

There was even a time when there were 130 children in the children's home - that's the maximum number I'm giving, because after that there were more or less 70-80, or 80-something. It varied. Of them, there were about 20-30 of the little ones, the under 3's in the nursery. They lived up on the 4th floor, they had their own nurses up there. There was a veranda up there, and the little ones played up there on that veranda. They never came down from the 4th floor. And downstairs we had a kindergarten, from 4 to 6 years old. And other than that we had children even up to school-leaving age. I didn't live in the same room as my daughter, she was with the other children.

No, I never got involved in looking out the children; they were brought to me. I was in the house, as a mom - I had a lot of children, each one different. I was there as the carer for the eldest group officially, but in practice I was the director. The real director was a very party man - he spent more time in the party, and in effect I ran the home. He's been dead for years. He was called Dawid Erdestein, a German graduate. I worked in that children's home 5 years. Some of the staff were Polish women. The carers were Jews. There was this one Polish woman, an older woman, who rescued Jewish children, everyone called her 'Nanny'. I can't remember what she was called, but in return for what she had done the Jewish community office gave her an apartment for life and work in our home. The children called me 'Pani Misia.' And it's stuck to this day.

The Jewish Children's Home was kept up by American Jews, and we would get parcels of clothing. The children were dressed very nicely, except I always tried to make sure that my daughter was dressed more modestly than the others. And a deputation of American Jews came to visit us, and the Cracow and province authorities were there. After a while a wagon came from America with decent beds, mattresses, clothes and bedding in it - everything we needed. Yes, and they didn't want to let that wagon through, because it was addressed in the name of the director, and they thought it was him trying to do some private deal, and he was nearly arrested. That guy Wiener, that cousin of mine, saved him. He went to the militia and explained it.

You weren't allowed to adopt Jewish children after the war. The communist authorities wouldn't allow it; that was the official position. By way of exception we managed to get just 2 children adopted. One little girl, who writes to me from Israel now - oh, I must write back to her. She even comes to visit me. And Teresa, who was adopted by a friend of mine, a teacher in High School No. 5 in Cracow.

I was fired on the pretext of smuggling children to Israel. Somehow they found out that I corresponded with relatives in Israel, which means somebody must have informed on me. They knew I was a Zionist, and that I had never been a communist. I worked there for 5 years, so it must have been 1951 or 1952 when they fired me. No, it wasn't Erdestein fired me, because he'd been moved before that. Some higher level teacher training course had been set up in Cracow - he was a teacher by profession and was made manager there. I moved to the Friends of Children Society. In my place they put some ex-head of a children's home in Lodz or somewhere. I don't remember his name any more. And when the children invited me to some get-together later, they said something about going away, but he said that his children weren't going anywhere. I said to them then: 'I'm going to Israel, so when I come back I'll tell you what it's like.' But when I came back they weren't there any more. They'd gone to Israel. The children who were still in the children's home invited me to some special occasion, and only then did I find out that there'd been some big campaign - organized from Israel - and they'd been taken. And the new director, who'd been so against them leaving, had been the first to go. Yes, with the children. And he died there shortly afterwards, apparently, because when I went to Israel he had already died.

My parents-in-law had left a house in Kalwaria, and in 1949 I sold that house. My husband had brothers and sisters, but somehow they all ceded at least part of it to me, so I had a little money and I was able to go on a trip to Israel. For a month, that was how much leave I had. That trip cost a lot. Actually, I'd wanted Halinka to go to Israel instead of me - after the war she was grown up. But she didn't want to, and we wouldn't both have got permission to leave the country. They didn't let people go to Israel, because they were afraid to let their precious Jews go. I had a lots of problems, I was refused permission to go several times, but in the end I succeeded and I went. That was in maybe 1952 or 1953. I thought that in time I'd persuade Halinka; I was brought up in a very Jewish home, but she wasn't; she was a Pole. Did I bring my daughter up in the Jewish faith? I didn't bring her up to be a Jew at all. She just has 'Jew' written in her papers. I'm not religious either, but I am a Jew by nationality. She doesn't feel Jewish at all.

I had plans to move to Warsaw, I had the chance of a good job, but Halinka didn't want to go; I had all sorts of problems. I took her to Warsaw, and she came back. So then I said: either you go to work, or you go to school. She was 18. She went out to work in her final year at school, took her school-leaving exams while she was working. Well, what did I have to live on? She worked 3-4 years in Huta [the Lenin Steelworks, built 1954, the largest industrial plant in the Cracow region, now the T. Sendzimir Steelworks]. Then she worked in Cracow as a Russian translator - after all, she'd been at school in Russia for several years. Then she did a part-time university degree, in Russian.

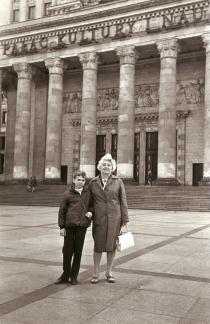

After we had to leave the children's home, Halinka lived with me at first. I found a tiny room at 48 Karmelicka Street. Then, while she was doing her degree she got married and I lived with her and her son [Ryszard Bronislaw, b. 1959], and her husband, a medical student, lived with his parents. When a room came free in my friend's apartment on Slowackiego Avenue, I moved in with her, and at least they could live together. Shortly afterwards Halinka divorced him. He moved out. His parents wouldn't let him back in their apartment. In the meantime, Ryszard was with me more than he was at home with Halinka, because Halinka was working. I worked too, but we managed somehow. He was sick a lot, had high fevers, so he didn't go to school, but stayed with me. I was constantly taking him on vacation or on trips. When Halinka was in Russia, he lived with me. She was there for 7 or 9 years, working as a translator. In Smolensk somewhere, then in the Crimea - various, in different places.