Yuri Fiedelgolts

Moscow

Russia

Date of the Interview: January 2005

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

When I called Yuri Fiedelgolts and asked for an interview, he refused first, saying that he did not feel very well. Then, he agreed for a short meeting.

I understood that it was hard for a man with poor health to recall dreadful events even to break the subject about them, so I was ready for a short life story of Yuri and his family. Yuri and his wife met me very amiably.

Yuri is a lean man of medium height. He has thick grey hair and bright young-looking eyes. Victoria, his wife, is a delicate, petite woman. She is calm and poised.

Those traits of hers must have been very helpful in the family life as Yuri is even now rather hot-tempered. They live in a 2-room apartment in an old house, located on the small quiet street in the center of Moscow.

The promised short interview turned out to be long and detailed. Yuri was carried away by his story line and his philosophy of life. Yuri was taken to Gulag when he was in the first year of the histrionic department of theater institute.

Of course, there was chance for him to resume studies after he was released from Gulag. During the interview I could not help thinking that the Soviet Regime had bereft us of a wonderful actor.

When Yuri was telling about a certain person, he did not merely depict him, but assumed his role- as if it was him in real life, talking to me.

- My family background

My father’s family lived in Gomel [Belarus, 320 km to the west from Minsk]. Before 1917 it was the territory of Poland, being the part of Russian Empire. [Partition of Poland] 1 Now Gomel is a district center of Belarus, being the chief town of the district. Gomel was a part of the Pale of Settlement 2, so there were a lot of Jews. There were several synagogues in Gomel and a large Jewish community. Jews were not merely craftsmen; there were also representatives of town intelligentsia. My grandfather Gersh Fiedelgolts was one of them. I do not know where my parental grandparents were born. They lived in other Belarusian cities when they were single. I know the family story how my parents were wed. They met when my grandmother was married and had two children. I forgot the name of the elder son, the younger one was named Shloime. The last name of grandmother’s first husband was Slavin, I do not remember his first name. My grandfather was a smart and handsome man. Besides, he was a good company. One day he met grandmother. I do not know the details, all I know that they fell in love with each other. Their love was crowned with bereavement of granny. She left her rich husband and two children and eloped with grandfather.

It was an improbable story for those times. They settled in Gomel. Grandmother’s first husband must have divorced her, so that they had a chance to get married. So they settled down in Gomel. I do not know what education my grandparents got, but they were educated people. Grandfather was a medical attendant, at that time the latter were much more educated and qualified than nowadays. Grandfather treated patients, even made uncomplicated operations. His patients were not always in Gomel. Quite often he was called to other towns. Grandmother was not a housewife after getting married, which was not customary for the married Jewish women back in that time. They lived in the center of the town, by the market square. Grandmother opened pharmacy right in her house. She was both the owner and a pharmacist. I do not remember my grandparents, as they died when I was a small boy. What I know about them is from my father’s tales.

There were 4 children in the family. Maria was the eldest. She was followed by the second daughter Asya (Jewish name Asna). Then two more sons were born- the elder Mikhail and the youngest in the family- my father Levi. My father was born in 1899. Later on, he was called Russian [common] name 3 Lev.

Grandparents were religious in spite of being educated. Jewish traditions were observed at home. Sabbath and Jewish holidays were marked. They went to the synagogue. Father enjoyed telling me about Jewish traditions, holidays, dainty things grandmother was cooking for the holidays. I remember father’s story how grandmother used to bake a lot of poppy pies of a triangle shape, hamantashen, and take them to her relatives and acquaintances. My father told me when grandfather carried out the first Paschal seder, father asked grandfather the traditional four questions as he was the youngest. My father did not tell me those things in detail to get me acquainted with the Jewish traditions - it was a mere idyllic recollection of the childhood. Any human being finds certain recollections from childhood wonderful and my father is like that. Moreover, father had a happy childhood.

Both father’s elder brother Mikhail and my father went to cheder at the age of 5. Father got proper Jewish education, but grandparents were aware that secular education would be important for the career. Boys went to the lyceum named after A.Е. Ratner, which was open in 1907. The doctor Arkadiy Efimovich Rartner was the founded of the school. In 1911 private Jewish lyceum accounted for 400 children, whose parents were mostly lower middle class and merchants]. It was the only private Jewish lyceum in Belarus. Of course, Jewish children were admitted there without 5%-quota 4, existing in Tsarist Russia. The studies at the lyceum were not free of charge. The Jewish children throughout Belarus came to study there. The lyceum students had the uniform and the cap with the lyceums blazon. Wonderful teachers taught at the lyceum.

Father was keen on mathematics. He said his mathematics teacher Krein, should be taken credit for that. Krein’s teaching method made all students take an interest in the subject. Besides, Krein was wooing father’s elder sister Maria, so they had even friendly relations, closer than teacher-student relations. My father succeeded in studies. Parents facilitated in that a lot. Not only grandfather, but also grandmother was very educated. Apart from being well up in pharmaceutics and Latin, she also was fluent in several European languages: French, German, English and Italian. My father was also fluent in those languages. At a mature age he looked up only for a special terms in the dictionary, terminology was the only stumbling stone. Grandfather had a great library containing the books in Hebrew and Yiddish as well as secular books in Russian and foreign languages. Grandfather had a large collection of classic music records. All those things were available to the children.

There were Jewish pogroms in Gomel both before revolution as of 1917 5, and during civil war 6. Father had to experience one of them in 1905. Pogromers were mostly the chandlers and sellers from the market. A huge crowd was moving towards the main thoroughfare of Gomel, crashing things on their way. They broke in Jewish homes, cutting the pillows and feather beds making the down flying around, breaking windows, dishes and furniture. There were even cases of beating and murder. My father’s family did not suffer form that. One of my father’s patients, Russian noble man, the officer, sheltered them in his house and did not let the pogromers to enter the house.

Having finished lyceum in 1916 father at the age of 17 went to study in Petersburg. There was a cult of medicine in the family and father was firm to become a doctor. It was very hard to enter the higher educational institution as there was a 5% admission quota for the Jews. Father was lucky and he was admitted in the university. There was the physiology chair on the faculty of the natural science, headed by the renowned and decent doctor-physiologist Leon Orbeli [Orbeli Leon Abagarovich Abgarovich (1882-1958) Russian physiologist, one of the founders of evolutionary physiology, academician of the Academy of Science of USSR, Academy of Science of Armenia, the Hero of Social Labor, general-colonel of medical service]. He ignored the admission quota for the Jews, and accepted as many Jews he considered appropriate judging by the results of the examinations and interlocution.

My father was admitted by Orbeli. Father was an excellent student and did well in studies. When the entire family moved to Moscow, father was transferred to Medicine Department of Moscow University. Father was in the fourth year. Later on in 1926, when the medicine faculty was transferred into 1st Moscow Medical Institute, father went to Moscow. Orbeli played an important role in the life, he gave the recommendation to the rector of 1stMoscow Medical Institute. Orbeli wrote in his letter that a very gifted student would come over to his university and he asked to assist. Father was not specialized in neurology, so he was sent to study to be taught by the famous neurologists. After graduation father was offered a job to teach at 1stMedical University. He became a post-graduate student, defended his thesis, he was an assistant professor, when he was teaching. He also was involved in practical work. He published over 40 works. Unfortunately, the Great Patriotic war 7 haltered his intention to defend the doctoral dissertation [Soviet/Russian doctorate degrees] 8, which was almost complete.

Father was a stickler of communistic ideas in the youth. He welcomed the revolution as of 1917. When the civil war was unleashed, father discontinued his studies and joined the Soviet army 9. as a volunteer. He also joined the Bolshevik 10 party. Father worked in the political department of the party, but he had to take part in the reconnaissance and in battles. He sincerely adhered to ideas of world revolution 11. Being an adolescent when he was in Gomel, he listened to the speech of Trotsky 12, which made a deep impression on him. Father told me how eloquent and convincing his speech was. Trotsky was a great orator. When the civil war was over, father came to the university and regained studies.

Father’s elder sister Maria got married in Gomel before the revolution. Her marriage caused a tiff between her and grandparents. Maria fell in love with a Russian man Voronov and he fell in love with her. Jews were not the only ones who did not approve of the mixed marriages. Orthodox [Christians], whom the Voronov family belonged to, disapproved such marriages too. Jews were especially intolerant as they thought they had enough from Russian pogroms, so they were against marriages with Russians. Neither Maria nor her husband received the blessing from parents, but still they decided to get married. There were certain complications in betrothal. Maria did not want to profess the Orthodox religion, but she had to become Lutheran for them to get married.

Grandparents were at loggerheads with Maria and her husband and did not keep in touch with them for a long time. They buried the hatchet only after Maria came to the parental house with the first born. First, parents did not want to see neither Maria not the child. Then the baby started crying and grandmother’s woman heart went pit-a-pat. She took the baby in her hands, and started comforting and tendering it. Since that time there was peace. After revolution, Maria and her husband moved to Moscow with 2 sons. Her husband was involved in foundation orphanage schools. There were a lot of vagrant children at that time. Maria finished the medical institute and worked as a doctor. In early 1920s grandparents and father’s elder brother Mikhail moved to Moscow. Maria helped them with the lodging and took care of parents.

Maria’s elder son graduated from the university. He was a zoologist, the professor of Moscow University. The younger, Stanislav, went through the WW2 and entered the military academy with the rank of the officer. He was a career military and retired as a colonel. Maria died before WW2. Her death was absurd. She was afflicted with highmoritis and she died from pain shock resulted in paracentesis of sinus.

Father’s second sister Asya was very beautiful. Having finished lyceum Asya went to Strasbourg and graduated from Medicine Department of Strasbourg University. She did not want to return to Gomel. She went to the Polish town of Przemysl and started to work as a dentist. She got married there. Her husband was a wealthy Jew, but much older than her, about 25-30 years. Her husband was also a dentist. They were well-off. They had a large house and servants. Both of them were popular with the inhabitants of Przemysl. They did not have children. In 1935 Asya came to see us and brought a lot of presents. She was confounded that my father was so poor, though he was an excellent doctor. She also was surprised with the friendly relations between «lords» (the way she called directors) and common citizens. She stayed with us for a while and came back to Przemysl. When in 1939 Poland was attacked by Germany, Asya did not want to leave the country, but I do not know why. As soon as Germans occupied Przemysl, her husband was shot like many other Jews and Asya had stayed in ghetto for 2 years and was finally shot.

Father’s elder brother Mikhail also graduated from the lyceum named after Ratner. He did not take effort in studies. Mikhail was capable, but he was lazy and negligent. That was the way he lived his life. Having finished lyceum He did not want to go on with his studies. He was at a loose end. He had odd jobs to get by. He did not have a family. During WW2 he was selling something on the market, and he was nabbed by militia men and arrested. He was charged with spivvery in the court and imprisoned. He died in jail in 1942.

Father’s elder step brother (grandmother’s son from the first marriage) immigrated to the USA before revolution. I corresponded with him before war. It was dangerous after revolution as the soviet power disapproved of those people who kept in touch with relatives abroad 13. People could be blamed in the espionage and imprisoned. Father was very watchful and was not very willing to answer the letters of the American relative. First he was the railroad worker, who installed the ties. Then he went to study and became an officer and finally came into money. He had a large family and he sent the photographs of his prosperous family. All of them looked American, very different from the local town Jews. They were well-groomed and smiley. They were well-off and I remember how I was impressed by that. I was amazed that they had a car.

In USSR it was a rare thing for people to own a car. Uncle always enclosed many beautiful stamps in the envelope for me. When I was arrested in 1948, father was seriously appalled in the period of struggle against cosmopolites 14. He had the relatives abroad and his son was «peoples enemy» 15. Father abruptly discontinued corresponding with the relatives and even did away with the correspondence and pictures of the relatives so there was no evidence against him. That was the only straw to hang on, so there was no other way to keep in touch with American kin.

The second step brother Shloime lived in Moscow. We rarely met. There is hardly anything I know about him. Of course, he is deceased as he was much older than my father.

Grandmother died in 1928. Grandfather passed away in a year. Both of them were buried in the Jewish Vostriakovskiy cemetery in Moscow.

My mother was born in Moscow suburb, in Bronnitsy [50 km from the center of Moscow]. I have never seen Philip Titov, my maternal grandfather. I know that he was the assistant of the merchant. The merchant was involved in the trade of tea and sent grandfather to China, Japan rather often. It was a very wealthy family. There were 12 children in the family, but I did not know many of them. I only remember three of mother’s sisters, who lived in Moscow- Anna, Tatiana and Maria. I heard about the rest from my mother. My mother Capitolina was born in 1899. She was the youngest in the family. Grandfather made sure that all his children were educated in lyceum, mother also finished the full lyceum course. There is a dacha place in the vicinity of Moscow, called Kratovo [40 km from the center of Moscow]. My maternal grandfather built 12 houses over there for each of the children. Of course of that property was sequestrated by soviet regime. My grandpa was reported missing. He must have been shot. Grandmother died during civil war.

Mother’s elder brother Dmitriy Titov went to study at the officer’s school after having graduated from lyceum. With the outbreak of revolution, Dmitriy joined Bolsheviks. During civil war he fought in guerilla squad. He was captured. The captives were taken away by train, which stopped at every station. Some captives were shot at every station as the edification for the local population. Dmitriy was lucky because the train, he was taking, was attacked by guerilla squad, which rescued the captives from Kolchak 16. Of course, Dmitriy joined the Bolshevik party. When civil war was over he became the prosecutor of the Siberia district. He settled in Omsk [over 2000 km from Moscow]. There were times of hunger and typhus fever epidemic in Moscow in that period. Dmitriy called mother from Moscow and found a job for her as the culture worker in the prison. Mother said that there several members of the Provisional Government 17 in that prison. Being a prosecutor Dmitriy was supposed to sign the fusillade lists. Soviet regime exterminated its enemies. It was deemed it would be better to shoot 10 innocent than to miss one guilty. Such a proportion must have been in the aforementioned lists. There were a lot of Dmitriy’s friends from officers’ school, who did not accept revolution. Of course, it was hard for him and he became demented. During one of his fits he committed suicide.

Mother’s second brother Alexander, mining engineer, lived in Petrograd and died from tuberculosis in early 1920s. Mother’s sister Serafima committed suicide. Another mother’s brother Konstantin Titov also committed suicide. During great patriotic war he was a private in the army and the officer slapped him because he had a bad stature. Konstantin pierced that officer with the bayonet in front of the aligned soldiers. Then he dashed under the train. There was an inherited predisposition to the mental suicidal disease in the family. Fortunately, mother was not affected by that. This is all I know about mother’s family.

My parents met, when father was practicing medicine and was in the last year of the institute, internship. He was assigned to hold internship in tuberculosis sanatorium in Moscow suburb. Mother was afflicted with tuberculosis as a result emaciation from hunger during revolution and civil war. The doctors sent her to the sanatorium for a treatment course. My parents met there and fell in love with each other. My mother’s feeling was even stronger than love – it was adoration, worshiping. I cannot even put in words. The picture on my table tells a lot about them. Father was looking ahead of him, and mother looked as if she only needed father in her life. It has always been like that between them.

- Growing up

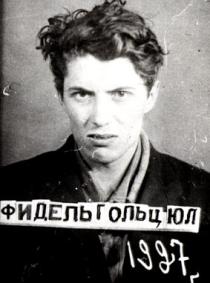

When parents decided to get married, father’s parents were not against it. It was the second mixed marriage in the family. Aunt Maria took the hardest hit. Grandparents were now complaisant to the father’s marriage. They came to love mother. But it was not that easy with the mother’s relatives. Not everybody approved of mother’s intention to marry a Jew. There were anti-Semitists among her kin. Mother made an ultimatum in the family – either her family accept father as their own, treat him with well-deserved respect, or she would not keep in touch with them. Mother was firm, at times tough. Her family must have accepted her requirements. Parents got married in 1926. They merely got registered in the state registration authority. They moved to the communal apartment 18 in Moscow working district. I was born in 1927. I was named Yuri.

Mother was on maternal leave, while I was an infant. When I was more or less independent, at the age of 5, mother enrolled on the courses of laboratory assistant. She worked in clinics of Moscow Medical Institute as a microbiologist- laboratory assistant. Mother was a good worker, then she was promoted even to the medical position though he did not have higher education. I was raised spending a lot of time outside. I liked all kind of escapades, hooligan pranks. I found my place among the local hooligans and felt rather comfortable among them. I had a lot of friends. There were Jews among them.

Lev Feigin, a Jewish boy from our yard, was my bosom friend in my childhood. He was short and plump. When we were about 6, both of us fell in love in one girl, also a Jew, Lena Tankus. But our rivalry did not stand in the way of our friendship. I enjoyed reading and collecting stamps. But I liked to fight as well. It seemed romantic for us, boys. We felt ourselves musketeers, pirates. We played all kinds of games in yard. We had so-called wars- when the boys from one house were at war with the boys from another house. Recalling those things I understand that it was in a noble and chivalrous way. Our disputes were settled by the duel- and nobody interfered in the fray. Our boys were referees observing the fight and making sure that none of the boys hides a stone or metal. The fight was face-to-face, only by using buffets and before the first blood. If there was blood, the referee stopped the fight and declared the winner.

Anti-Semitism was concealed in that time. I remember there were times when father was walking along the yard and local youngsters were crying out: «Fiedelgolts is walking by, Fiedelgolts is walking by!», and I understood he was not very pleasant to hear. Sometimes I heard somebody say carelessly «little Yid» [Yid is a pejoratory way of calling Jews in Russian]. At that time people watched out what they said, not like it happened later. I was very touchy in childhood and maybe that was the reason why I felt that. At home my parents always convinced me that people were equal in our country in spite of the difference in nationality. andthere was no way we could have racism. If somebody hissed so offensive words, he could be judged for that. It was true, before war many people kept silent, having grit their teeth.

When I turned 7, I went to compulsory Russian school, located nor far from our house. There were a lot friends from the yard in my class. I was a good student mostly because of capability rather than sedulousness. I went through all required stages at school: was a pioneer 19, Komsomol member 20. Both my peers and teachers treated me well.

In 1937 mass repressions commenced [Great Terror] 21. I was in the 3rd grade, so I could not understand the political meaning. I had my personal worries. In my childhood I was friends with two boys –Zerkalovs, who lived in our house, and studied in my school. I did not know their father, but their mother was a rigid woman, who also wore a red kerchief on her head. She was a worker at the plant of the rubber articles Caoutchouc. She was an ordinary proletarian woman, a communist and was a leader among common people. Her sons were good boys, and many guys from our yard kept friends with them. In 1937 she was arrested and both of her sons were taken to the orphanage. I have never seen them again. We lived in a poky room in the communal apartment.

Our neighbor’s son Latsek stood out from our boys from the yard. Latsek wore a checkered suit and we teased him by calling him ‘bourgeois’. I often called on Latsek. His mother, an elegant blond, often took us to the cinema. We watched all children movies, which were released. I envied Latsek, when his father’s car was driven in the yard. Latse’s son often went for a ride. Once I asked to take me for a ride as well. Then in 1938 Latsek’s father was arrested. I remember how Latsek’s mother gloomed, her features sharpened and her dresses did not seem so elegant and unique. Latsek stopped playing with us in the yard, and was hiding. When my parents found out about arrest of Latsek’s father, my mother asked me not to play with him, otherwise all of us would suffer. I felt some tension at home. I think it was a fear for arrest. My father never broached political subjects, he even avoided that among his friends. At that time our family was not touched.

During my childhood soviet holidays were always celebrated at home. My parents were very buoyant. They invited a lot of people for celebrations. We had fun. Our kin and friends came over to have a good time dancing, singing, staging home performances. Mother was friends with father’s elder sister Maria. Father’s brother Mikhail. Mother’s sister Tatiana also came over very often. The relative from both sides admired our family. Love between my parents was worth fascination. My father was worshiped as he did well in science. Father was a developed man- he was well-up in literature, music, mathematics. Of course, he focused on medicine, and neurology. Aunt Tanya always used to ask mother why Lev was always with the books.

I admired my father. Sometimes I was scared of him. He might punish me by slapping my cheek or I could get a box in the ear. His punishment was fair and unavoidable. He was just, so I never bore grudge against him. I would even forgive injustice only because of father’s talks with me. Father came home, had dinner and invited me for a walk. We were strolling in the street and could talk on any subject. Sometimes father’s friend from lyceum, mathematician Shneerman, also joined us for a walk. He became academician at the age of 24. Both of them talked to me as if I was equal and I imbibed their words.

My father knew very many different people. Of course, many of his acquaintances were doctors. He met with Lina Stern 22. They spent hours on talking about medicine. She came in Moscow from Switzerland in the middle 1920s and stayed in the USSR. She was captivated by the communistic ideas and was eager to help soviet regime. She taught at Moscow 2nd Medicine Institute, and was the head of the chair. She was an interesting person, the zealot of medicine. She did not marry and devoted herself to the science. She spoke only French. During war she was the member of the Board of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee 23, and was arrested during Doctors Plot 24. Fortunately, she was exonerated after Stalin’s death 25. Father also knew the sister of the great poet Mayakovskiy 26. He also knew actors and musicians.

Father had a peculiar Jewish feature- he liked to banter at his interlocutor or the subject of the conversation. He liked the humor. I remember his talks with mother at night. Sometimes I could hear what they were talking about as we lived in one room. There were times when father touched the subject of Stalin’s personality. Father was skeptical to Stalin. Coming of intelligentsia father took Stalin as a nouveau riche and barely educated man. Father was skeptical to Stalin’s views.

- During and after the War

On 22nd June 1941 we found out about the outbreak of war from Molotovs’ speech. He said that Germany violated peace treaty [Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact] 27 and attacked USSR. Of course, we were confounded, but I was sure that the war would not last long. Soviet propaganda was constantly making us convinced that our army was the strongest in the world, and any war would be finished on the territory of the adversary within days. We had stayed in Moscow by October, 1941.

In middle October 1941 state of the siege was declared in Moscow. We with colleges and students of the medical university we were evacuated in Central Asia. First we came to Tashkent[over 3000 km from Moscow], wherefrom we went to Namangan. We did not stay there for a long time and finally stayed in Fergan. Mother noticed hostility coming from Uzbeks when we came to Tashkent. The life of local people became harder with the surge of so many evacuees. Food cards [Card system] 28 were introduced, prices for food escalated. People were starving, getting sick and the evacuees were blamed for that. Besides, Uzbeks were drafted now though they had never been drafted before neither in Tsarist army nor in Soviet. I remember the wail of women when they were seeing off the draftees at the platform of the train station.

Then Uzbeks on purpose caught venereal diseases in order to avoid the draft. Father was assigned the member of the medical board of the military enlistment office. He told me how young guys came over for commission and proudly declared that they were syphilitic. First the afflicted were sent home, but when it turned out to be in masses, they forced the boys to go through medical treatment and then they were sent to the front anyway. Local inhabitants were also blaming Jews for that. They said that their children perish because Jews are not at war. There were local Bukhara Jews 29, but the Uzbeks treated them well. Though Bukhara Jews were looking very much like Uzbeks, having the same manners and clothes.

They were also considered local, but they were antagonistic towards the evacuated Jews. Apart from working in the medical board by the military enlistment office, father also worked in the military hospital. Anti-Semitism was thriving there. I could felt it at school as well. Some of the teachers were evacuated Jews from the Western Ukraine and Poland, who came over here to escape Germans. Of course, they were very different as they were assimilated. They were Jews only by blood, but they did not know their language [Yiddish] or customs. Local students ignored such teachers and made anti-Semitic remarks in the middle of the class. I was hot-tempered and was always ready to fight after being insulted. Mother had to come to school rather often and hear complaints against me. She had never reproached me though.

Only father worked in evacuation. Mother had to take up the hardest job- to feed us and to get foods by the cards. She had to spend almost the whole day in the lines. Sometimes we starved, because all we had she gave to father. It was the most important for her that father was OK. Mother did not only forget about herself in her cherished love for father. She also forgot about me. I felt hurt, and I envied those children whose mothers took care only of them in the first place. At times I even thought of leaving home. To a certain extent, mother was right neither I nor she worked, and our father was the only bread-winner. But still, I do not think it was the main factor for her. In evacuation father was afflicted with typhus fever and survived only owing to mother’s care.

I was missing Moscow so much during evacuation! When in summer 1943 evacuated were on the point of return to Moscow, I was also eager to home. Father could not leave his job, and mother could not leave father. I talked my parents into letting me go by myself. It was decided that I would stay with mother’s sister Tatiana before parents’ return. She lived in Kratovo. Father made arrangements with the trainmaster of the military and sanitary train and was sent to Moscow. On my way to the aunt I saw many devastated houses. Many people still had not returned. On the fence of the house I saw a sing in bold font written by chalk: «Fight Yids and save Russia!». I was shocked by that line as well as by the fact that nobody had erased that.

I came back to school. Anti-Semitism was in the full swing. I did not feel it towards me as I was among my friends from childhood. I had to receive passport at the age of 16. There was the section in the passport called ‘nationality’ 30. Before getting my passport it was the first time when I heard from my mother that it would be better for me to be Russian. I said that I would have written Jewish in my passport and mother had never touched the subject again. It was my well-thought intention. My last name was pure Jewish Fiedelgolts, how could I say that I am Russian...

When I was transferred to the 10th grade, I entered preparatory department of the Steel Institute. I met Jew Boris Leviatov and Russian Valentin Sokolov. We were the boys from intelligentsia families. We used to discuss all kinds of subjects starting from the sense of life and up to the political disputes, Stalin’s dictatorship and NKVD 31, subordinated to Stalin or Nietzsche 32 and all kinds of things. Each of the interlocutors was trying to show off his erudition depicting the revolutionary hero or the movie character. Nobody could ever perceive what would be the outcome of such games of ours. It was a mere adolescent romance and the desire to stand out. After preparatory course we did not keep in touch. Leviatov and Sokolov were drafted in the army and I did not enter the steel institute. Parents were insisting for me to carry on the family tradition and to become a doctor.

Mother was the most persistent as she was in love with the father and she wanted me to follow in his footsteps, thinking that only father was doing the right thing. I was convinced that I would have a bright future; fathers name would help me in the first phase and then I would become a good doctor myself. I entered the Medical Institute and in my first year I understood that it was not my cup of tea. I did not stand learning things by rote- having to memorize 200 different names of canaliculate for one temporal. When we had to work on anatomy, I finally understood that I did not want to be a doctor! I still remember how I was sent to the basement to take formalinized corpses for the anatomy class, then I was forced to make a ripping cut cranium with the help of the saw. I still remember those splashes on my face. I could not stand it and decided to leave the institute. In 1947 I entered Theatre Institute, the Department of actor's skill. It appealed to me. The teachers were happy with me and they said I would have a bright future. I was an avid reader. I was took an interest in the history of the theatre, biographies of great actors. I thought I liked what I was doing. I was happy. I was not interested in politics at that time.

At the end of the first year in 1948 I was arrested. I was taken straight from the classes and sent to the department of the reconnaissance SMERSH 33, located at Kropotkinskaya street. It is still there. They needed at least a formal confession of guilt for my case to file to court. I was pushed hard in the house of detention. I was blamed in foundation of the anti-Soviet circle and participation in its activity. Then I found out that Valentin Sokolov was the stooge. At that time I thought that he did it because he was a coward, being afraid of the beating and torture. In the 1990s I had a chance to look at my case and I saw the reference to be submitted to the martial court stating that Sokolov was the agent of the KGB Secret Service 34 and had the nickname ‘Rodionov’. I did not pay that much attention to that. Maybe that reference was one of KGB schemes. Who knows, may Sokolov was the agent. At any rate, the case was filed against the three of us. Sokolov was the witness at the line-up, both with me and Boris. When the search was made in our house, they found my diaries. They played an important role on the trial and were used as material evidence. I described all kinds of events in my life in the diary and admitted rebellious thoughts. It was the time when the struggle was actively taken against rootless cosmopolites and the three of us perfectly fit the article.

I would have run amuck if I had been interrogated longer. The sleuths were putting both moral and physical pressure. There were two interrogators- ‘kind’ and ‘evil’. The kind one, captain Demurin, looking very polite and proper, was as if protecting me. He said that I was kept in the house detention because my comrades on the freeside would have killed if they had found out that I was anti-Soviet with counterrevolutionary ideas. They, interrogators, are here to protect me from the public perturbation and wrath. They would make a man from me. I would go in the camp, do some physical work and come back home being strong and healthy and say: Hello, mama! I should not think of suicide, just to confess in mistakes and sign where it is required, and keep on living with a clear conscience. Such were the words …

The second one was hitting hard on the table and yelling: «You scum, Yid mug!». His family name sounded Russian, Maximov, but his appearance looked purely Jewish. It was the time when the employees of the ‘punitive agencies’ had the alien names… Maximov was constantly deterring me, making threats. He also resorted to beating. He was taking the interrogation minutes, where fibs were written in a beautiful handwriting and orthographic mistakes. Once he gave me such protocol to sign that I hurled it in his face. First he shook my stool with his leg, and when I fell on the floor, he hit me hard in the abdomen, and then in on the head. I lost consciousness and I was hauled in the corridor. When I came around, I was taken back in Maximov’s office where there was another colonel, a good-looking one. I did not know who he was. Maximov and I had squabble. When Maximov saw me, he ordered the guard to give me a double mattress. I was happy. I did not have a mattress in my cell and I hoped that I would sleep off! It turned out that ‘double mattress’ was a wet cell, located in the basement on the level with metro, where he could here the clatter of trains. Water was dripping from the walls and from the ceiling, the wooden bunk was drenched.

There was no place to sit, nothing to say of lying down. I was constantly feeling sleepy. It must have been a protective mechanism of my organism to relieve constant strain. I was about to swoon and was ready to fall asleep even standing. The turnkeys did not let me sleep. I do not know how long I had stayed in that cell in a semiconscious state. When I was being to the interrogation and had to walk along the ‘warm’ corridor as compared to the cell, I felt chilled. Now I was interrogated by a kind sleuth. He asked me with a tender and ingratiating voice why I was flagellating myself and was looking like the rack of bones. Then he told the guard to bring me a sandwich with the cottage cheese and a cup of coffee with milk. He also told me to eat and ponder over whether it was time for me to confess. Again there were interrogations … Then they were sick and tired of me and sent me to the prison for ‘additional effect’. Those people framed a mythical anti-Soviet organization from our circle, consisting of three people, and enjoyed awards and promotion. My father was also affected with my arrest. He was interrogated for couple of times. It was very rough and humiliating. They even used expletive words and threats. Of course, it was very unpleasant for him. By the way, during interrogation they kept on saying that father and I were Jews.

When our case was in the court, my parents hired renowned attorneys. My father hired attorney Otsep, the professor of jurisdiction, a great lawyer. Father’s colleagues told him that he was making me a high-class funeral by hiring Otsep. They were right- his services cost a lot of money, but the result was predetermined. The trial took place in the premise of martial court, located in Arbat [the main promanade of Moscow]. I remember that during the trial Otsep could not bring forth any defense arguments. He was putting an emphasis that I should go through the medical examination at the institute of the court psychiatry; because he was sure that I was demented. That was all he could come up with. All he said looked so cowardly, and everybody noticed that. He was trembling and feeling afraid.

Then the prosecutor, lieutenant colonel Vinogradov, took the floor. His face was in high color. He looked muzzy. Looking straight in Otsep’s eyes he said that it was strange for a famous lawyer to talk like a pro-American cosmopolite and he said he could not comprehend whether Otsep was a soviet person or not? I saw the famous Otsep cower. He was despondent ands kept silent by the end of the trial. In accordance with the article 58 [It was provided by this article that any action directed against upheaval, shattering and weakening of the power of the working and peasant class should be punished] we were charged with anti-soviet activity, they also added item 11, group actions. We were sentenced to 10 years in the maximum security camp [Gulag] 35 (we were lucky to be sentenced to 10 years, we might have got 25), and we were bereft of rights for five years, i.e. exiled. I was also sentenced to hard physical labor as the most malicious criminal. The three of us were separated. I was sent to the maximum security camp Gulag, located 4000 km away from home. I was sent to work on the automobile repair plant. I had not stayed there for a long time.

My wretched parents managed to get the permit to visit me in the camp. I did not know how they had done that – usually political prisoners were not allowed to have dates, besides I did not stay in the camp that long. My parents came and saw me for couple of minutes in the presence of the guard. Shortly after seeing my parents I found out that I was included in the squad to be sent to Kolyma 36. I think my date with parents also affected my fate– certain type of the prisoners was not to have any contacts with the free people. Those who violated that condition, were punished. Our squad was put in the crammed car for cattle and taken to the port of Vanino, where Kolyma camp was being formed. There I met a young Moscow doctor, a Jew, Joseph Malskiy. He was sentenced to 5 years in camp as a socially jeopardous person. His parents, old Bolsheviks were repressed and he was arrested for being their son. His wife and a little daughter stayed in Moscow. Joseph knew my father. We decided to stick together and help each other.

Our squad came to Vanino Sea Port [port town in the Russian Far East, 4500 km to the North-East from Moscow]. Let me dwell upon things I noticed in the replacement depot. Now there is nothing of the kind. Only from tales of those who were there, one can imagine that horrible picture. A spacious territory bounded by the sea, and circled by high blind fence and watchtowers, was divided into rectangular zones and cordoned with the rows of barbed wire. There were low clapboard barracks, located parallel to each other. There were 4 zones. One of them was taken by criminals, the other ones by ‘suka’ [Bitch, a curse in Russian. In this case it refers to rapists and murderers, rascals and traitors, people, who came down – the most dangerous and despised category of prisoners.], the ones who were at fault with their criminal accomplices, i.e. a robber, who gave testimony against his accomplice and others who violated the laws of the criminal world. The next zone was called– «mayhem»: deserters, card-sharpers, sadists, rapists and other riff-raff. And finally we, sentenced as per article 58 ‘fascists’ as we were called. It was not allowed to mix those categories neither in the zones nor in squads: they did away with ‘aliens’ ruthlessly, and a quick death would be a mercy.

Each zone had its own laws and orders. The privileged caste was criminals, whom the authorities called ‘social close’, whereas we were called ‘socially alien’. Criminal authorities were calling shots at Vanino replacement depot and in the camp. Of course, they had certain benefits from the guards. Their food was cooked separately and was much different from the scraggy potage the ‘fascists’ were having. Like we say in modern times, it was a well organized mafia, which had contacts with the camp authorities. There was a collective guarantee: «You concede, and I concede». The head of the zone made some concessions to the criminals under condition that they established order. The criminal leaders assigned the strongest and the cruelest criminals to be the foremen for them to make ‘fascist’ work. The criminals were not involved in hard physical labor, political prisoners were supposed to do their daily work as well as the daily work of the criminals. Some of those criminal leaders looked rather imposing, like scientific workers for instance. When looking at them it was hard to picture that each of them was tried for several times and was involved in deaths of many people. By the way, I also noticed that there were quite a few Jews in the criminal world. These were so-called ‘intellectuals’, who were using rather grey cells than hands. I did not see robbers-murderers among Jews-criminal leaders. They were genius thieves – con artists, the so-called generators of the ideas and steps for larceny.

There were the following zones at Vanino replacement depot: administration, decontamination zone, sanitary zone, hospital, where really feeble people were taken. Our squad was taken to the sanitary zone, because our train was from the camp, wherein was the outbreak of some kind of epidemic. The most appalling was to be sent to Kolyma. We had to exert our every effort to stay here as long as possible to postpone the trip to the place, wherefrom would be no escape. Malskiy and I decided to probe the option with the sanitary unit as it was possible to stay here with the steady job. The head of sanitary unit, a young lady, lieutenant dressed in the uniform with the white robe over it, suggested that Malskiy should look into the next zone. In her words recently doctor and medical assistant were killed with the knife, and there was no one to supply for them. We had to agree, as we had no way out. Joseph did not want to go there by himself, so he introduced me as medical assistant.

We went to the sanitary unit. Nobody convoyed us; we were shown to the inpatient-department for 20-30 people. There were double plank beds instead of the bunks. The regime was totally different from our political zone. Even the turnkeys were kind of home-looking people. The convicts, dressed in coats and suits were walking around the zone. We were not allowed to wear civilian garment. If we did, we would be sent to the lock-up cell. We wore striped wrappers. Hardly had we come in, fierce looking criminals, tattooed all over rushed the room and offered us a deal: we were supposed to give the criminals places in the in-patient clinic for them to escape the squad to Kolyma and the most important thing was to provide that pack with the drugs, it was morphine, on regular basis. Many of them used the drugs and for that they offered their patronage.

Many of those ‘mayhem criminals’ turned out to be interesting people, gifted, preserving certain human qualities. Levka Bush was one of the criminal leaders I met at Vanino replacement depot. First there were rumors in the zone that Bush himself would be coming to Vanino with the next squad. I was curious what kind of person he was to be so revered by the gangsters. Soon, I had to meet him. Joseph and I lived in small room by the barrack of the sanitary unit. All of a sudden, the door was open and some people were taking the suitcases in front of us. Then a huge guy, a body guard with two knives in his belt, stood in the doorway. We were sitting still, and a rather high-brow young man, truly Jewish, dressed in fashionable coat and tie came in. His face was immaculately handsome: thin classic profile, a goatee and beautiful almond eyes. He came up to us and said very politely. I still remember his worlds and the pitch of his voice: «Doctors, let me introduce myself, Lev Bush. I am a big collector, I am drug addict, and my syringe went bad on my way. Could you borrow me one from your arsenal? You would not regret doing a favor to me».

Of course, there was no way we could refuse him. moreover he made a pleasant impression on us. Joseph suggested that he should stay in our sanitary unit as a patient, and Bush was happy to agree. He settled in our sanitary unit. Bush behaved like a lord. His servants, criminals, made bed for him, took off his boots and cleaned them. Our sanitary unit looked much better now: there were mirrors on the walls, snow white linen. Cakes and wine were brought from the free side. The management overlooked all that, because such criminal leaders were calling the shots in the zone, and established a relative order. If they were taken away, there would be constant scuffle and massacre. Bush enjoyed talking to us. He considered us his ‘equal’ and was eager to tell us about him. Bush’s father was the KGB colonel.

When Lev was about 14, he was seduced by a housekeeper, who was connected with the criminal world as it turned out. She was his first woman and totally putting him under her thumb. She forced him work for her by selling the stolen things on the market. Of course, he was nabbed, was tried and sent to the camp. He left the camp and got the criminal education. His ‘job’ was complicated, requiring intelligence and – Bush robbed banks by using forfeited documents, produced by him. He was a professional con artist – collector. The guy was also the artist among the forgers (counterfeiters) being able to forge any stamp, he knew the handwritings and signatures of many dignitaries in militia. It goes without saying, he might become a good famous artist under different circumstances, alas! Though, Bush was a criminal he sincerely despised his ‘colleagues’ specialized in marauder and murder. He had such qualities as kindness, tenderness, compassion to the suffering of common people. That young, brave and handsome man took a keen interest in philosophy, art and books. We often conversed about different subjects, discussed books and performances. Lev strove to understand whether there was justice in the world and how to exterminate the chains of slavery.

He could not stand being imprisoned and escaped many prisons and camps. The last escape to Vanino was unsuccessful in spite of office’s uniform and forfeited ID certificate. Unfortunately, I do not know what happened to Bush, though I would like to know. There were other Jews. There was one Jewish pickpocket Yashka, good humored and nimble guy from Odessa. He was called diamond fingers for his fine work. Mechanism of red tape legal proceedings swept the weeds like orach and wheatgrass together with the grains. “Re-upbringing’ in the camp did no good, and incurred recurrent crime and contagious deceases. Very many fates were crippled. What to say about our article 58. In the replacement depot we found out that ossification and sluggishness of our criminal investigation department and legal department as a whole, were incompetent as compared to the criminal world, rapidly changing its strategy and applied with new facilities. Hard-core offenders knew the Penal code and laws better than militiamen and lawyers.

We treated dysentery in the zone during the outbreak of epidemic. At times, we had to give criminals some drugs and put them in an in-patient clinic. We could not hospitalize all of them, and some were discontent. However, as compared to the previous camp doctors we managed to cure patients, soon we respected. Then the replacement commenced. More and more squads of the criminals were taken onboard of the ship. They stopped sending us the drugs. Once, at night, a pack of the criminals broke in our room, pushed us to the wall and started ransacking the room. Then Joseph was told to follow them in the barrack. They did not ask me to, but I joined Joseph for him not to be by himself. The criminals blamed Joseph for hiding the drugs and not saving anyone from the trip to Kolyma. We leaned against wall and were waiting for our fate to be decided. There were 2 of us against 200. They could kill us any minute, but luckily there were some of them with common sense. One of the criminal leaders, Uzbek with the nickname Ugolok [Nook] stood up for us. Joseph saved him when he had the overdose of drugs. Squabbles and discord started and we were taken back tacking advantage of the hassle. In several days both of us were assigned in the support staff of the ship for prisoners ‘Ermak”. The holds with the 3-tiered bunks, were crammed with prisoners. We were placed separately in a small section under the ladder. We were given two backpacks- one with the medicine, another with canned fish and bread. We had to service all holds.

Beside Malskiy and me there were some more medic workers-prisoners. We were allowed to walk around the deck. The guard soldiers took off the heavy lids of the holds and took us down. Suffering prisoners, craving for medical assistance were waiting for us in dim light. Rocking, puking, stench, excrements, turoid water in rusty kegs, rime on the lags. Water splashes from waves reached the deck. The rigging was covered with ice. It snowed for couple of times. So Ermak entered Nagaisk bay, breaking through the icy waters. At nights we were getting settled. Being the medics we first were put in a very clean and tidy barrack of the sanitary unit, pertained to the central replacement depot. Then we were sent to the ‘mayhem’ zone. We had to run away from there. We found out from pickpocket Yashka that we would be in trouble as there were some angry people plotting a murder. Our roaming on the replacement depot seemed to be over when we settled on the zone of robbers, but it did not last long. I was taken from there and sent to Berlag 37 accompanied by severe convoy. Our trips with Malskiy diverged.

Again, I became a mediocre worker, no different than the rest. Again I was given the toggerty: sailor’s jacket, quilted pants and jacket. There was a painted number on our toggery, and it could be seen from distance. There was the same deaf and humble mass of heterogeneous people: Latvians, Estonians [Deportations from the Baltics ] 38, Ukrainians, politzei and former militaries, as well as such people as I ‘peoples’ enemies’.

I was double pressed in the camp. I was ‘peoples’ enemy’, who could be beat and robbed by any ‘socially close’, besides I was a Jew. There were people who served for German police, the fascist agents, flagrant anti-Semitists- Lithuanian, Estonian, Ukrainian and even Georgian nationalists, who served in German fascist groups. They were elbow deep in Jewish blood. The administration and the guards were also as anti-Semitic as them. I do not know I was managed to survive. It was a miracle. I took all anti-Semitic escapades very acutely. I was involved in fights and did not spare myself. I was not that physically strong, but I was rather decisive and could stand up for myself. I would never let anybody push me under the bunk. Such a person was reckoned finished, and anyone could tease him without being punished for that.

I was ready to face death rather than face disgrace. I fought tooth and nail. I turned hot-blooded during the fight and felt neither pain nor fear. I was not afraid to be killed, nor I was scared to kill. They were scared off from me like from a rabid dog, and watched out. There were all kinds of things before I gained such a status. In my first camp in Berlag I was attacked by a very physically strong man- anti-Semitist. He was saying something like ‘beat the Jews’ and tying to hit me with a heavy wooden swab. I understood that he could break my spine, cranium. One time when he brandished with the swab, I managed to dodge, but I understood that I would be over with if took a hit. I did not have anything to use as a weapon. I jumped on him and clenched my teeth on his neck. He fell down.

All kinds of people attacked me with the sticks, clubs and fists trying to unclasp my mouth. I could feel the taste of his blood, and some abdominal feeling was aroused in me. I did not want to let go of him. They managed to unclamp my teeth and turn me out from the workshop. I could not break his throat, but he was so scared, besides he was left with the scar. Of course, authorities found out about that and I was put in the lock-up for five days without bread and water. When I left the lock-up being feeble and emaciated, I came up to that man the fist thing and whispered in his ear ‘I would finally kill you, viper’ and swore like a bargee. I gave him such creeps that when he saw me he was bowing to me from the distance. He was really funky. It was the law of the jungle, but it was better to be governed by the law of jungle than by the law of meanness. It is my opinion. But it is story still went on. I was called in the administration of the camp. There were several people. The officer asked me why I had attacked the criminal. I said that when a man who was elbow deep in Jewish blood, called me ‘Yid’ and began beating, I had not choice but protect myself and sell my life at a higher cost.: «You even cannon kill, this is your weakness». he meant ‘Jews by ‘you. I did not say anything. Of course, if I killed the guy, I would be added 10-15 years to my sentence.

There was another case in the workshop. There was a Ukrainian nationalist in the workshop, who had been saying insulting things against Jews all day long. I still was feeble because of the lock-up and kept silent. Then he put a rotten rat in the spindle of my tool. When I turned it on, the rat came out and was about to hit my face. I came up to him and asked: «Was it you. He smirched and said yes. I took the hammer from the bench and him on the forehead hard. He fell. His buddies were chasing me along the workshop thrusting sledge-hammers and crow bars at me. Of course, they might have killed me. The guards transferred me to the barrack of the fortified security. Then I had to stay in the lock-up for 20 days until it would be known whether the guy would survive or not. I was lucky that the guy survived and they did not expand my sentence. In short, I had to protect myself in any cost. I was not crouching. I despised and hated people who succumbed to the rough force, and fawned up the nihilities. I still hate them.

Still, I was lucky to meet good people there, who supported and assisted me. There was even one Ukrainian nationalist, who liked me. He just adored me. He said: «Yurko. You are Ukrainian, you are no Yid!». I waved off and he still used to say that. I met a lot of intelligent and interesting people in the camp. There was the period when I worked in the crew of Lanskoy, the offspring of general Lanskoy [Lanskoy, Peter Petrovich (1799-1879): Russian adjutant Genaral (1849) and General of the cavalry (1866)], of the second husband of Natalia Goncharova, Pushkin’s wife 39. He was an intelligent man with a good stamina, the officer of the old school. He had a good attitude towards me, he was not anti-Semitist. There were immigrants from Kharbin, Mukden, Manchuria, who also treated me right. [Russians who left Russia during the revolutions and the Civil War.] I cannot say that only extremists and monsters were in the camp.

I was closer to the Jews in the camp. Beside the Jews sentenced in accordance with article 58, there were Jews who escaped from Hitler during war and came to USSR. They were from Poland, Romania and Hungary. They tried to escape the Hitler’s camp in the country with the equality, where no anti-Semitism and oppression were observed. Of course, they learnt all those things from Soviet propaganda. They ran away from Hitler and came to Stalin and were hospitably settled in Gulag. They took the hardest hit. The convicts were allowed to receive several parcels annually. I cannot say how many exactly. Parents send me the parcels and shared the products, sent by my parents, with the Jews-fugitives. They had nobody to send them the parcels. I remember a Hungarian Jews, the doctor Grosberg, a very pleasant and smart man. There was a Romanian humpty-dumpty old man. He was disabled, so he worked in the support staff of the zone and had a miserable life. I also fed him. Before alignment and getting off to work we grouped in five. Then we were recounted and taken to camp work behind the gate. Suddenly I saw that the convicts swung the roly-poly and threw him at me crying: Yura, hold your roly-poly Yid!». I caught him and told him not to be afraid of anybody.

In 1951 I was transferred to the camp, to the north from Berlag. It was a huge working zone, where the foundation, walls and constructions of some secretive site were made. It must have been some plant. There was no warm season for the people living in moderate climate of Russia, in Kolyma, but the winters there are even hard on the local people. In the previous camp I was mostly working in the workshop, where it was not so cold, but in frosty winter as of 1951-52 I was to work in the open. I did not work on the construction site for long, as I turned weak. Such guys as I were called hatracks- the candidates to the cadavers. I was transferred to the auxiliary squad consisting of such hatracks as I. The foreman of the crew was Nikolay Bibrikov, the offspring of general Bibikov [Bibikov, Alexander Illich (1729 - 1774): Russian state man and military general, Associate of Catherine the Second]. He was my peer.

He was raised in the family of the immigrated former White Guard 40 in Kharbin. He was most likely sentenced because he belonged to the old noble generation line. He was a proud and well-mannered man. We made friends. Our crew was supposed to clean the territory of the camp, but we could not cope even with that work. Bibrikov could barely move because of being so week. Nobody made him work, he sat with the rest by the fire and remembered the old stories and sang old Russian Romance songs in sotto. Later the crew was dissolved and Bibrikov and I were sent to the barrack of the fortified regime. When it was 50 Celsius degrees below zero, we were sent to chisel the icy bottom of foundation pit. We were supposed to go down 5 meters deep. From the top we were given the tub to load the dug earth. The tub was taken up, emptied and taken down again. We had to watch out not to be hit. We had an almost incessant labor for 10-12 hours per day. We could get warm only in movement. Once, the group of the camp administration came over to the verge of the pit. One of them decided to crack a joke: «Hey you, Bibrikov! How inconvenient it is here! But your relatives were used to luxury». Bibrikov raised his head and glazed at the soles of the people standing on the verge of the pit and said out loud :

«I loathe you!». Such a bravery could end in his death, but the administration slowly withdrew.

There were a lot of criminals in the fortified regime barrack, the food there was better than in any other place in the camp. Sometimes we had even had extra helpings. When we were off that barrack and were allotted to the working crew, we were starving again. Our nutrition was very poor: oat gruel, rotten herring, underbaked bread. All that food was in skimpy portions. Sometimes were given stinky boiled fish instead of the herring. In order to prevent scurvy there was a keg with pine infusion.

In early spring 1952 I was sent to another place along with 300 convicts. We got on platform trucks and took the herringbone position- one person sat and moved legs apart so the other one could sit as close as possible. It was made for the security purposes of the convoy for the prisoners not to escape. The trip in the trucks was emaciating though we did some halts. We had been joggling hitting the road pockets all days long. Then we took the ferry boat across a rapid river Indigirka beyond Ust-Nera. At last we reached the final destination. It was the extreme point of Kolyma –Alyaskitovy. That God-forsaken place was about 900 kilometers away from Magadan, far from the high way. There was ore mill in Alyaskitovy: the upper camp with tungsten ore mine with waste banks and mine, and the lower camp with beneficiation factory, sand banks and hydraulic rocks.

There were 2 zones: there were about 1500 convicts, who serviced the ore mine, and the other zone consisting of 500 convicts worked on the beneficiation factory. Tungsten was a metal used in the defense, so the mill was secretive being positioned in such a far-away place. There was a small settlement of the civilians and even the cemetery for them on the slope of the bald rock. The cemetery for the convicts was 15 kilometers ahead, half way between the factory and the ore mine. It was fenced with barbed wire and empty watchtowers in each corner. Convicts were buried there without a trace- there was just a sign with the number. The notch was surrounded with bold mountain with setts.

First I was sent to the upper camp, to the ore mine, but I was hold up there as I had a myopia. I was transferred to the lower camp to work at the beneficiation factory. 500 convicts worked in the lower camp. The toggery we were given was used by two or three people before with large variegated patches. All of us looked like clowns. The barracks were crammed with bunks from wall to wall. Then our clothes had one color- being covered with dirt. There was a canteen and a culture barrack. There was a tidy road between the barracks, covered with sand. There were big boards with annual and quarterly performance ratios and cheerful slogans calling upon honest and bona- fide labor, assisting in reforming. The new-comers were allotted in the crews. I was sent to the factory crew, servicing assembly lines looking like metallic boxes the vibrating metallic nets inside. The factory was down the slope. There was a horizontal water sink in the last corps. Toxic water was trickling down there, taking away the processed gob- white sand. On the photo it looks like it is a river or lake, but is a large puddle, contaminated by waste waters. The dump is to the right. Ore was crushed in the 1st or 2nd corps. It was delivered by hoist cranes in tubs. The crushed mass was poured in screener and griddled out. Larger fractions were additionally ground in the 3rd corps. Ore was flushed with water, then taken in the funnels and finally to the re-griddling in our assembly lines, whereby the convicts worked with the spades.

The mechanism was turned off every half hour. There was a moment of silence and the rattle was off. Our crew consisting of 10 people, was in a hurry to ‘take off’ the rocks to get to the tungsten concentrate, pouring out the upper layer to wooden tub. Then the master switch was on and machines were on. The crew sat around the tub and assorted wet rocks, putting aside those where tungsten could be seen. The rest was taken to the belt of the transporter, which took the selected rock with the penultimate workshop. The rocks were griddled on the huge vibrating ‘tables’, then it was processed with alkali and acid. There was a worker by each ‘table’, fixing the layer of the output and picking the useful threading. The slag was made only of sand. There were drying chambers on the sides of the last corps. The beneficiation factory was heated in the winter time.

Elderly men and disabled were forced to work. They managed somehow. The work was exhausting. There was a cloud of dust. No respirator helped, the convicts were afflicted with silicosis [chronic lung disease caused by inhaled dust for a long time. It is characterized by the developed pulmonary fibrosis], and died in the camp hospital. My working place was damp. The clothes did not dry out after work. Good thing that during severe frost when metallic parts of tractor levers were cracked, we worked in a warm premise. Those who worked by the ‘tables’ were intoxicated with alkali and acid. Drying chambers were considered to be pandemonium. People were choking with toxic evaporations there. The frosts reached – 60°С. When the water in the flume throat was frozen, we were sent down the mountain to break the obstructions in the exit throat of the flume. We hammered the ice coat and expanded the exit to get rid of the ice so the sand could move through the flume. Wet sand was coming from the top freezing off immediately to the felt boots and the clothes. Those who were performing works under the flume were in the frozen sand almost knee length.

The second shift was breaking the ice with the pinch bars to get them out of the sand. Only in the drying chamber they were released from the heavy ‘cuirass’ when the frozen mass melted and strew off. It was the way people were breaking through with the performance exceeding the standards by 20% -50% percent. There were certain complications. The convicts were made to dig the exploring shafts 4-5 meters deep. Then the convicts were taken down the exploring shaft with the bucket to take the samples from the rock. Of course, no fastening or other safety precautions were observed. Very often the primitive method ended in a tragedy: the worker was covered with the loose sand in the exploring shaft. The most optimistic scenario if he was unburied before he had suffocated. Otherwise if he was suffocated nobody was responsible for him. The person was just crossed out from the list and none would be the wiser.

A Georgian, Nikolay Dzadzaniya was our foreman. He was brave and decisive. His was sentenced to 25 years, and the term was prolonged because he murdered the camp worker. Of course, having such a term he had nothing to fear and nothing to lose. He established an apple-pie order and discipline not only at work, but in the pastime. Of course, he had succeeded in that by manipulating the feeling of fear. However, Dzadzaniya was just and honest and did not hurt anyone for no reason. He never extorted the parcels sent to the others. Our crew was multinational. There were two more Georgians beside Nikolay: an amiable bumpkin Aliko Meladze and an old man Dzhashi. Meladze studied at Tbilisi university. His father was the secretary of the state committee of the party of Georgia. After his father was shot Aliko was sentenced to 25 years in camps. He loved his motherland, Georgia, so much. He recited me the verses of the Georgian poets in his native language. Dzhashi served in the German punitive squad. He had the same term as Meladze. Dzadzaniya was the deputy foreman. He was a calm young Armenian, Stepanyan.

The team of workers consisted of Russians, Ukrainians, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Polish Jews and guys from Baltic countries. The jailbirds used to call it jokingly ‘complete zoo’. I remembered the last names of Polish Jews: Kotlyar and Delfer. I was friends with Kotlyar. He was a brave and physically strong and calm man. He was in the camp, located closer to the South and after was sent to Aliaskitovo after having committed a murder. Former polizei, a fascist was the foreman in Kotlyar’s previous camp. He started teasing Kotlyar having found that he was a Jew. Kotlyar had no other way, but to kill the polizei. His 25-year sentence was doubled. In the course of time the members of our crew became bonded. I made friends with my peer, Western Ukrainians and Lithuanians. Those, whose sentence was short- 2-5 years, were getting ready for the free side. They were reading books in mathematics and physics. Others were doing arty-crafty jobs in leisure time- making beautiful knick-knackories with straw incrustation and sold them to the civilians. At time we watched movies. We also had amateur performances.

The mill fulfilled the plan and exceeded the target quarterly and annual plans yielding high profit. But was it reflected on us? We, the convicts, only were given the credit, when we exceeded the target. We were told that those who regularly exceeded the target, would be paroled. But nobody left the camp on parole. Every day we got up in the wee hours and hastily were brought to the roll call, then to the collection point. I remember the daily precept of the convoy: «Attention, convicts! Do not step from row to row, move without dispersing, no lacking behind and smoking. Step to the left or step to the right would be considered the attempt to escape and the guard will be shooting without a warning. Infuriated dogs were barking behind us and breech mechanisms clattered. Each convict was counting the days and could hardly believe that he would be pardoned. How could we live to be free if we could not see people two steps ahead of us because of the toxic dust.

Primitive respirators bothered us even more, it was difficult to breathe with them. 90% of people ended up in silicosis. Rheumatism and tuberculosis were incurred when working in dampness. But still we thought it was better to fall from physical fatigue than having an easy job to run amuck from desperate thoughts. We had one day off per week, but we spent it by cleaning the territory beyond the zone. Cleaning scavenge heaps in the settlement, working with the pinch bars and picks. We also had to rebury cadavers, hastily buried in winter time during severe frosts. There were little joys as well. Apart from the convicts there some civilians and exiled worked on the beneficiation factory. There were even girls. They got here as per mandatory job assignment [Mandatory job assignment in the USSR] 41 after graduation from the mining college. They worked as foremen supervising production processes. Of course, they were informed that the convicts her were villains and beasts, fascist scum, guilty of death of the best people. Of course, after such information girls were keeping away from us. They inspired us: we could enjoy looking at free girls and it was like God’s send to us.

Approximately in the middle of February 1953 we learnt from the civilian workers at the factory that Stalin was unwell. We knew that there were constant round-ups on the radio regarding his health and we were aware that he was on the brink of death. Of course, each of us was waiting for that hour to come, but our expectations were different. On the 5th of March 1953 we found out about Stalin’s death. Through the fence we could see the mourning flag flaunting over exile area. We were locked in barracks. I cannot say we were rejoicing. All of us were in stupor. Some people were gladdened, but still frightened. All of us had one thought- what would happen with us. Nobody hoped for the better. We were afraid that even a tougher dictator would wield the scepter and exterminate all of us. We also feared that the guard would be lynching. Anything might have happened in such backwoods. But I felt neither great joy nor sorrow. Then we had timid assumptions about amnesty, but nobody could take it serious. We were discussing the candidates and the prospective successors. We had been locked for 2 days. Then the regime on the zone became less rigid, we were even paid some money for the work. A small grocery store was open. Soon Beriya 42 issued a decree on amnesty,but it was not referred to us the political. Only criminals were under amnesty. Our hope became forlorn.

In early 1954 I got ill. First, I had ailment feeling giddy from the languor and hyperhidrosis. Then I was getting a fever in the evening. When I had to go to work in the morning, my temperature was OK. There was no doctor in the camp. The position of the chief camp physician was taken by the wife of the prison principal. She had nothing to do with the medicine. Before work I came to the sanitary unit. She thought that her job was to exposes the malingerers, who wanted to escape work. Therefore, she made me take off my shirt and kept watching while I was taking temperature for me not to do any tricks with the thermometer. Then she sent me to work. When I said that I did not feel well, her response was that my mother alternative was a lock-up, if I was not willing to work. Pulmonary hemorrhage started in the workshop and I was taken to the hospital in the stretches. I had stayed there until next morning and was pushed to work.

Only when the hemorrhage did no stop until the morning, the chief doctor understood that she had overplayed. I was sent to the barrack for disabled crammed with dying people. I got more and more feeble every day. I was a bliss for me. I did not have to go to work. Nobody pushed me to get up, there was no convoy… It was serene and quite. The doctors did not bother to come; there was no medicine. We were hardly fed, but I had no feeling of hunger. I was lying in my bad feeling happy and waiting for the death to knock on my door. The only medical assistance I got were injections of calcium chloride. Strange as it may be –they helped and my hemorrhage stopped. I am not sure what kind of outcome I would have if I were not called by the management and read the order on my pardon in the middle May 1954. It was the time when the campaign on the investigation of the cases of the innocent convicts was being held. The lawyer, mother of the Boris Lyadov, filed appellation in the supreme court, the collegian of the martial court regarding our common case.

When our case was reconsidered, the Supreme Court left the charge in accordance with article 58- anti-Soviet propaganda, but cancelled item 11- the criminal group. Thus instead of 10 years of camp, we were supposed to have only 6, but we were in the going on the 7th year. Thus, we were to be released. We had to obtain the deed on release and process the documents for the exile in Ust-Nera. Several convicts were sent there in the body of the truck. We were accompanied by a lieutenant. The convicts gave me the letter so I could drop them in the mail box so they would not undergo preliminary censorship. In Ust-Nera we stopped in the tea café and I bought stale cookie, which got hard like a stone. It is difficult for me to put my emotions in words. We were sent to undergo a physical. After being X-rayed they told me the terrible diagnosis- silicosis. It was a spread disease among ore mine workers incurred due to permanent dust. That news gloomed my joy of being free. Silicosis is a malady past cure.

The difference was that I was not to die in the barrack section for disabled, but on the free side. I was told to come back to Alyaskitovy. Since the camp administration was to blame for my production malady, they were supposed to take measures at their cost and send me to the home for the disable wherein I was to stay until death. Nobody was going to take me back to Alyaskitovy, I was supposed to think of that myself. The two of us, I and an elderly Chechen guy, also sick, we plodded to bald peaks. We were in the camp toggery and the dwellers of the house on our way were hiding and locking doors, when saw us. We spent the night right on the curb of the road and in the morning we were picked up by the dump truck heading to the upper camp. I met uncle Grisha, the room orderly from our working barrack. He was standing by the administration premise. It turned out that the tacit man was also released. I asked him what he would be doing on the free side. He said that the camp administration offered him to stay and work with the documents, but he did not want to stay in that damn place any minute. Probably surprise was written on my face, and uncle Grisha took the photo from the pocket- a valiant colonel having a lot of awards. It was impossible to recognize Grisha in him.