Victoria Behar

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Zelma Almalech

Date of interview: September 2002

Family background

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

My ancestors came to Bulgaria as early as the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century after the persecutions in Spain [see Expulsion of the Jews from Spain] 1. Then Bulgaria was under Ottoman rule 2. The native language of both my maternal and paternal grandparents was Ladino. I even remember my sisters and cousins and me made our grandmothers speak Bulgarian and mocked them a bit because they didn't know it well. They also spoke Turkish.

My paternal grandfather's name was Aron Bohorachev. He came from Kiustendil, a town in South-West Bulgaria. I don't remember him because he died in 1929, when I was only one. My grandmother's name was Sara Bohoracheva. I don't know her maiden name. She was a housewife and a very affectionate woman, who looked after the family and us, her grandchildren. Every time we asked her how old she was, she would say that she was very old because she remembered the times of the Turkish rule.

I don't know about my grandfather, but my grandmother never went to school. She lived a long life and moved to Israel in 1949. She lived with the families of her children there and received a small pension. She died in Israel, but I don't know when. I don't know about my grandfather's family, but my grandmother's was very large: She had three brothers and three sisters. One of her sisters is my second grandmother, my mother's mother. People called her Franca, but her real name was Devora. So, my mother and my father are first cousins.

My grandfather on my mother's side, Bohor Komforti, was a flour dealer. I will always remember him in his brown, coarse clothes, sprinkled with flour. He had his own business - a medium-size one, according to Bulgarian standards. He didn't have any employees and worked every day, except for Saturdays. His clients knew that he didn't work on Saturdays. My grandmother Devora was a housewife; she looked after her children and grandchildren, both in Romania and in Israel. They dressed in the same way as the Bulgarians. There was nothing special in their clothing, except that my grandmother always wore a kerchief on her head. Their house was very beautiful, and there was also a yard. In the summer we all gathered there, mainly the children.

There were three sisters and three brothers in my mother's family. My mother, Ester Bohoracheva, nee Komforti, was born in Dupnitza, a small town in Western Bulgaria between Sofia and Kiustendil, in 1905. When she married my father, she moved to Sofia. Her brother, David Komforti, died very young. Her second brother, Rahamim Komforti, lived in Plovdiv and was the director of a cigarette factory. The third one, Jacques Komforti, stayed in Dupnitza and helped his father. My mother's sister, Rosa Komforti, died of Spanish fever during World War I, in 1918. All her siblings emigrated to Israel after the war.

My father, Iacob Bohorachev, had two brothers and one sister. His oldest sister, Rosa Aronova Bohoracheva, was born in 1892. Avram Aronov Bohorachev was born in 1894 and died at the age of 87 in 1981 in Israel. I don't know when Isak Aronov Bohorachev was born, but he died very young.

My father was the youngest son. He was named Iacob at birth, but they called him Jacques, and he was known by that name everywhere. He was born in 1900 in Kiustendil and died in 1977 in Israel, in a kibbutz near Kfar Saba. My grandfather was married before and had six daughters from his first marriage. My father often mentioned their names, but I have forgotten them.

My aunt Rosa lived in Pernik, Uncle Avram and my father in Sofia. They weren't very religious and only observed the high holidays, mainly at home, where the whole family gathered. My father only went to the synagogue on the high holidays, and mostly alone. He very strictly observed Yom Kippur and fasted. On Pesach we had the seder. My mother's family was more religious; they ate kosher food, observed Yom Kippur, and the whole family gathered on Sabbath.

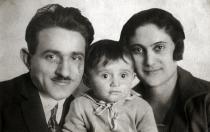

My father didn't complete his university studies in economics, but he nonetheless worked as an accountant in a knitwear factory. My mother graduated from a junior high school, but she didn't work so that she could look after my sisters and me. I'm their eldest daughter. I was born on 1st June 1928. Elvira is the second oldest; she was born on 5th April 1932. My youngest sister, Devora, was born on 11th December 1936. We were all born in Sofia. We spoke Bulgarian at home and Ladino only when my grandmothers came to visit. We also lived in Dupnitza for a while, where we were interned to on 3rd June 1943. We came back to Sofia in October 1944.

We lived in the Jewish quarter near Bet Am 3 and the Great Synagogue 4, but then there were smaller synagogues, too. We had a house with a yard in which there were only flowers, and my friends and I played mostly there. Our house had three rooms. We had running water and heated the house with coal and wood. My mother did all the housework by herself. My parents kept in touch mainly with their relatives, as our kin was quite big, and most of their friends were Jews. My father was very close with his employer, Gotse Gulev, who was the owner of the knitwear factory. His employer's family helped us a lot during the Holocaust. When my mother had her appendicitis operation, his wife, Elena, took my younger sister and me from our grandmother, who looked after Uncle Avram's children then. And Elena looked after us until our mother got better.

We observed almost all religious traditions at home. All holidays were properly celebrated, for example, on Yom Kippur our father didn't allow us, children, to eat either. It was hard, but we obeyed. My father was a very strict man. But he went to the synagogue only on Rosh Hashanah and on Pesach. We celebrated the holidays mostly at home. I loved all holidays very much, especially Pesach, because then we received new clothes and shoes, and I loved eating burmoelos 5. Traditions were observed in the family circle. We celebrated the high holidays at home. I remember that we used to organize a children's fancy-dress ball on Purim.

Every summer we visited my grandmother in Dupnitza or my uncle in Kiustendil by train - this was at the beginning of the 1930s, during the summer holidays. When we were younger, we went only for one or two weeks, but when we started going to school, we spent the whole summer vacation there and played with our cousins. We didn't go on holiday to other places. It was around that time that I traveled by car for the first time. My uncle Rahamim, who lived in Plovdiv, had a car. He would drive to Kiustendil and take us on a ride around the suburbs. On the Christian holiday of Archangel Michael my father's employer would prepare a special dinner of boiled mutton for his employees and would come to take our family in his car. What I also remember from those years is our father taking us to a restaurant from time to time to eat kepabcheta [grilled oblong rissoles].

As a child I went to a Jewish nursery school where I studied Hebrew. My sisters didn't go to kindergarten. We studied in a Bulgarian school in Sofia. Afterwards, I entered the 1st grade of the French College 6. My favorite subject was chemistry. I didn't have a favorite among the teachers because they were all very considerate and exceptionally tolerant. I only visited the religious classes in the Old Testament. All Jewish students in the college were exempt from the New Testament classes. If someone wanted to, they could go to those classes, but we didn't. We were friends with everybody, regardless of nationality. As for my spare time and friends, the times then were more patriarchal and my father was a strict man, so I mainly stayed at home. I didn't take part in the events of the Jewish youth organizations of the time.

Although I was in the French College, I very much wanted to continue to study Hebrew and I enrolled in classes at the Jewish school, which were for people who didn't study there. But I only went a few times because the Defense of the Nation Act [see Law for the Protection of the Nation] 7 was passed. The rights of the Jewish population were limited and my parents forbade me to go there, as they were afraid that something bad might happen to me. Soon after that, the Jewish school was closed and all Hebrew lessons were stopped. I could only go to the regular school.

During my childhood in Sofia and the vacations in Dupnitza I never experienced a bad attitude towards us because we were Jews. Everyone in the college was also very tolerant. But after the Defense of the Nation Act was passed and we started to wear the yellow star [in 1942], we were forbidden a lot of things - to have our own business, to go out on the street after 8pm, to visit public establishments, such as restaurants, cinemas, etc. At that time I saw that many people from our quarter were also Jews - we recognized them only by the stars. On 24th May 8 the Jewish students were forbidden to take part in the traditional students' manifestation in the center of Sofia. My Bulgarian classmates proposed that we, the Jewish girls, should take part like all the rest despite the decision of the authorities. But our teachers, who were nuns, and loved us very much, persuaded them that this could do harm to the college and to us. So, we gave up the idea of participating, but after the manifestation we celebrated in the school with the rest of the students.

All Jews from Sofia and the larger Bulgarian cities were interned to smaller countryside towns. Some of my relatives were interned to Vratsa, a small town northwest of Sofia, others in Kiustendil. Only Uncle Rahamim from Plovdiv wasn't interned. The Jews from that city were prepared to be deported the first to the Nazi camp, Treblinka. But the citizens of Plovdiv led by Plovdiv's Bishop Kiril 9 didn't allow this to happen. We were interned to Dupnitza on 3rd June 1943 and went to live in my grandmother's house. They allowed us to take only the most necessary things and my parents started selling out our belongings fast and almost for free.

Then Gotse Gulev, the owner of the knitwear factory, where my father worked as an accountant, and his wife, Elena, came and told my parents to sell nothing and that they would keep our furniture until all this was over. My mother was desperate and told them that we would never come back, that we would be sent to the death camps, about which we already knew. We had heard about them from friends and acquaintances outside Bulgaria, from the independent Bulgarian newspapers with correspondents abroad, who wrote about the echelons of death, and from the French girls in the college. [Editor's note: Although the interviewee insists that she was aware of the existence of the German death camps in Poland, this is unlikely. Most Jewish interviewees who we have interviewed understood that 'deportations to the east' boded ill for them, but none guessed that actual death camps were in operation. Holocaust historians Raul Hilberg, Wolfgang Benz and Randolf Braham have written extensively on how the German regime worked to keep these camps a secret. It is also unlikely that Bulgarian newspapers, which were all under government control, would have written of such things, especially when the Bulgarian government was an ally of Hitler's Germany]. But Gotse Gulev and his wife told my mother that such a monstrous deed couldn't go on for long. He even sent two of his employees to Dupnitza with us to see how we would settle and where we would live. Later, I found out that on 24th May 1943 10 when a big march in support of the Jews was organized by Bulgarian intellectuals and representatives of the Orthodox Church in Sofia, Grandfather Gotse - I called him Grandfather because he loved me as if I were his granddaughter, and so did I - also took part along with Exarch Stefan 11.

Grandfather Gotse managed to arrange for my father something like civil mobilization on the grounds that he was indispensable for the factory. So my father went to Sofia every month for a week to work and he was paid as if he had worked the whole month. They were wonderful people, but later they also had a tragic fate. I had to interrupt my education because only one Jew was allowed in a class with vacancies in Dupnitza. There were no vacant places for me and I had to complete my 5th grade [the last but one class of high-school] as a private student. Unfortunately, my father couldn't find all the textbooks I needed and it was extremely hard for me.

We were forbidden to pass along the main street in Dupnitza after 4pm and we were absolutely banned to go out on the street after 8pm. But one day I had to send a letter to my father, who was in Sofia that week. I only had to cross the main street; this was all that we were allowed to do. It was around 5 or 6pm and on my return, in the Jewish neighborhood, a Jewish boy, who was a friend of ours, took me quickly to their place, because the Branniks 12, along with the police, were organizing a manhunt against the Jews. I spent some time at their place, but I was afraid that my family would be worried about me. In the end, the Jewish family let me go, so that I wouldn't be out after 8pm, and the situation outside also seemed calmer.

But, suddenly, as I was walking, two Branniks jumped out on the street next to the river where we lived and where we had the right to walk. Policemen came and took me to the police station; there were also other Jews there who had been taken from the streets without them violating the curfew and with no other reason whatsoever. They left us there the whole night, and we had no idea what would happen to us. We waited and we asked, but they only told us, 'You'll stay here!' At around 3 or 4am they told us to leave our ID cards and they let us go. An uncle of mine was also among the arrested and we went home together. Later the police told my mother that she had to pay 200 levs to get my ID card back. This was unimaginable terror.

That year, since I was studying as a private student, I found it very hard when we went back to Sofia and I had to continue my education. The anti- Jewish laws and our internment practically crippled my education. I had my grade officially recognized, although I had only sat for my singing exam, because 9th September 1944 13 came and all students had their grades recognized. The new power had come; the Soviet armies had reached Bulgaria. We were allowed to go back to Sofia.

My father went to our house to tell the people living there that we were coming back. When he came to Dupnitza, he told me that he had signed me up in the French College for me to continue my education and that the teachers would give me textbooks. I went back to Sofia alone in October 1944 carrying the curtains my mother had given to me so that I could tidy up the house until they had prepared the rest of the luggage. Then Grandfather Gotse and his wife Elena took me to sleep at their place so I wouldn't be alone in the house. And since at the time of our internment to Dupnitza my parents had sold their bed, they bought them a new one. They were such good people. I still have this bed! All my family came back to Sofia and my sisters continued their education, after an interruption of one year, in an ordinary Bulgarian school.

In 1946, during the nationalization by the communists, Gotse Gulev's family was interned to Vratsa and all their possessions were taken away. They both fell ill a little later and within a year both died of cancer. They weren't allowed to go back to Sofia to have treatment, and they had done only good things in their life...

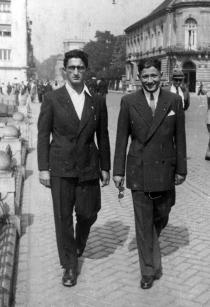

During that period many Bulgarian Jews started moving to Israel [see Mass Aliyah] 14. Whole families and kin gathered to decide whether to leave for Israel. I remember that my mother's whole kin gathered at our place and decided that they wouldn't leave. That was in 1948. I had already graduated from the French College and had a boyfriend. It is a romantic story. While I was a student in the upper classes, I often met on my way to the college a tall, slightly swarthy soldier, who was always smiling at me. This also happened when I was with my sisters or friends and they noticed it. My parents somehow learned about it and they told me that I could have for an intimate friend, and later for a husband, only a Jew and I should have no illusions about this soldier. Particularly after his Holocaust experience, my father had told me that he wanted no Bulgarian for a son-in-law. And my sister was telling me all the time how this tall and swarthy soldier was staring at me. I started thinking that he was Armenian or Turkish; he didn't look like a Bulgarian to me. Then, one day, some relatives and friends from Dupnitza came to Sofia and we met some other friends of theirs outside the cinema. My wooer from a distance was among them. We were introduced to each other and it turned out that he was also a Jew.

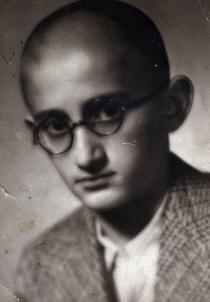

His name was Jacquelen Iacob Behar. We started going to his Workers' Youth Union [see UYW] 15 club together. He was an active member of the UYW. After two years we got married. I never looked at him until I found out that he was a Jew and then I fell in love with him. Jacquelen was born on 3rd February 1926 in Sofia. His family wasn't rich - they were workers. They weren't religious. His father entered the socialist movement right after World War I. When Jacquelen was young, he was a member of the communist youth movement. During the Holocaust his family was interned to Vratsa.

When we found out that my family wouldn't leave for Israel, my boyfriend and I decided to apply to Sofia University and continue with our education. I loved chemistry, but I had studied French in college and I failed on the test in Bulgarian language. I made the foolish mistake of not applying to study French philology and so I remained without a university education.

My boyfriend and future husband started studying pedagogy. As an admitted university student Jacquelen went to a youth brigade 16 and I started working. Everything was going well, we were already talking of marriage and when he came from the brigade, we quickly got married. Meanwhile, despite their former decision, all my mother's relatives had moved to Israel. She remained here alone and along with my father decided to leave, too. So, I either had to marry quickly, or leave with them. And I chose Bulgaria because of my love for Jacquelen.

In fact, my parents moved to Israel in a little dramatic fashion. At one point my mother wanted me to tell them whether they should leave or not. It was clear then that I was staying with my husband in Bulgaria. Then they decided to leave and started packing. One day I came from work and saw the trunks unpacked. I asked what was going on and in the meantime my father came home, too, and he asked my mother the same question. And she said that she couldn't leave without me, she couldn't leave her child behind... I felt very bad that I was an obstacle to their decision - I neither wanted to leave with them nor stay here without them.

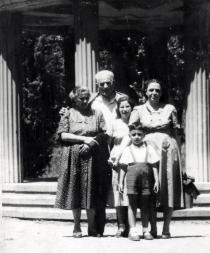

This was at the beginning of April 1949, but, after all, they left for Israel on 7th May the same year. They settled in a kibbutz near Kfar Saba, where some of their grandchildren still live. They were mainly involved in agriculture. My mother died in 1974. My sister Elvira has a son and a daughter, two granddaughters and a grandson. She died in the kibbutz in 1987. My other sister, Devora, died in a car crash in Israel in 1980. She had four daughters and a son, and now she has many grandchildren, but she is gone.

Jacquelen's family didn't want to move to Israel. His father became a member of the Bulgarian Communist Party as early a 1919 and they believed that they had to stay in Bulgaria to build socialism and communism. Now I regret that we didn't leave and took his parents with us, too. But it was our fate to stay here. My parents' families had never been interested in politics and they were devoted to their work and families. When I went to Israel for the first time with my little son Eli to visit my parents in the kibbutz, my father wanted me to stay in Israel, but my older son, Emil, who was nine years old, had remained in Bulgaria then and my husband was also in Sofia. They had become my family no matter how close I was to my parents and sisters. My father came to visit me in Bulgaria and always argued a lot with my father-in-law and my husband about politics.

My father-in-law worked as a director of one of the few big stores, then called 'Naroden Magazin' [a public store]. He found a purse for the wedding for me. I had a white shantung dress from my student years, my mother-in- law gave me a pair of white shoes and that's how I got married. Our marriage was only before the registrar because at that time the communist authorities had banned religious marriages regardless of the religion.

I started working in my father-in-law's store. My son Emil was born on 27th February 1950, and my second son, Eli, on 19th November 1955 - both in Sofia. When the children were born and there was no one to help me, I started to do sewing in piece work from home. This kind of work was organized for old people and women with little children. At one point, however, I could no longer work that way and I started working with the state tourist company Balkantourist, where I worked for 19 years as a clerk in the administration until I retired in 1983. My husband attained the highest academic degree, associate professor in pedagogy, and his particular specialty was pedagogic psychology at Sofia University.

In my work I've never had problems because of being Jewish. But during the trial against the Jewish doctors in the Soviet Union [the so-called Doctors' Plot] 17, my father-in-law was director of the Kazanlashka Roza company [a company producing and exporting rose oil in Kazanlak - a small town in Central Bulgaria at the foot of Stara Planina]. Once after the export of a certain quantity of oil by plane - it was the first time that rose oil had been transported in that way - it turned out that the container was only two-thirds full on arrival. He was put on trial and the implicit reason for the charge was that he was a Jew. A colleague of his, a physician, proved at the inquest that the decrease of quantity was a result of some laws of physics, when rose oil is exposed to great heights, and he was acquitted. But the trial affected his reputation. And yet, he and my husband remained firm communists.

We brought up our children to be aware of their Jewish identity, but also to follow the communist ideals. We told them the truth about the persecutions of the Jews during World War II. As for Israel, we explained to them that regardless of the differences in ideology, every person has the right to make his or her own choice and by going there our relatives had made theirs.

During all these years it was extremely hard for me - I loved my husband and my children very much, but I also missed my relatives who were far away in Israel a lot. My father was anti-communist, and my husband's family were communists. When I first wanted to go to Israel in 1959, the Bulgarian police didn't allow me to, but my husband managed to arrange it and they finally let me go. I was so happy that I would see my relatives after ten years. Out of worry, I developed an allergy, which I get even now when I'm nervous. I traveled by plane with one stop in Athens. When my younger son and I boarded the plane, I felt such excitement!

Yet, my father could never fully understand how much I loved my husband and that I couldn't live apart from him. I missed him and my older son so much; at the end of the third month in Israel I was dying to go home. I felt the same way after the wars in Israel and the breaking up of the diplomatic relations between the two countries. It was very hard for me, but fate decided this way. I was very excited during my visit to Israel, but I also felt a bit insulted as far as Bulgaria was concerned because the people in Israel thought that Bulgarians lived in poverty and had nothing to eat. I also think that during their visits to Israel some people complained far too much in order to receive more presents to take back home.

After 1959 I never saw my mother again. My father came to Bulgaria once at the beginning of the 1970s. He stayed for a month and every evening he argued with my husband about political issues - they never reached an agreement. My father defended Israel's position, and my husband the position of the then communist countries.

Now both my sons have two children. Emil has two daughters, Victoria and Silvia, and Eli has a son, Victor, and a daughter, Daniela. They both graduated from university - Emil is a pedagogue like his father, and Eli is a pharmacist. My husband and I wanted them to marry Jewish women, but they both married Bulgarians. The way of life in a Jewish family is different from that in a Bulgarian family, even though they live in the same country. My husband and I even wanted them to see more of life before marrying. But it was their decision. We had told them that there is no such thing as divorce in our families, but two years ago Eli divorced his wife. It's all fate. They both identify themselves as Jews, but I couldn't take them to Bet Am to take part in the life of the Jewish community. But now I'm happy that I was successful with my granddaughters, who also feel like Jews. I only failed with my grandson, Victor.

I've never been a member of the Communist Party. But I lived in such a family and after the changes in 1989 [following the events of 10th November 1989] 18, I think that despite all that was said then and is being said now about these 45 years, we lived better then. We lived better because we had a secure job, there weren't so many beggars, no prostitution; no such crimes. Well, there were maybe a few hundred people who lived better than us then, but the rest as a whole lived better than now. To take my family as an example: I could always afford to bring my grandchildren some present then, and I can't afford it now.

It wasn't right to build the Berlin Wall and divide one people. But when it fell, a lot of bad things were said about communism. Maybe I take all this to heart because these changes affected my husband badly. He died on 30th July 1995 in Sofia. He was seriously ill.

Now, there is once again some drama in my family - everyone is working very hard without a break. The daughter of my older son Emil, Victoria, works with the first private national television, the bTV, and I can't see her. This is also true of my sons and my grandchildren. I go to Bet Am for two hours every day, to help the group of older Jews, with whom we eat there. However, it's not like home. My daughters-in-law, although they aren't Jews, learned the Jewish cuisine, but they don't have much time to cook at home. We have never gathered for the Jewish religious holidays, only for New Year's Eve - they go to celebrate it with some friends on the eve itself, but the next day they come home. But now, they don't even do that any more. I know that they love me very much, they help me financially, but I want to see them more and they are so busy.

Nowadays, there are some attitudes towards us, Jews, that worry me. Even during the Holocaust in Bulgaria, the anti-Jewish laws didn't make the Bulgarians anti-Semites. On the contrary, they sympathized with us, helped us. I told you what wonderful people the family of my father's employer were. And now, I hear all the time, that we, the Jews, are ruling the world, that we are the most well-off nowadays. Let's not talk about the Holocaust any more. I feel bad when I hear such things. I feel particularly bad when I hear them talk about Solomon Passy, the present foreign minister of Bulgaria, complaining that a Jew is leading the Bulgarian diplomacy. He is a Bulgarian citizen, after all!

My parents' families weren't deeply religious, but all Jewish holidays were observed mostly by all relatives getting together. My father went to the synagogue twice a year - on Rosh Hashanah and on Pesach. I also continued this tradition, and so does my family. Especially after my husband died in 1995, my peers and the older Jews from Bet Am became my family. At home I keep some things to remind me of the past - photos and albums, the videotape sent to me by the Steven Spielberg Foundation after my participation in the Shoah project [Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation]. The people at Bet Am take good care about us and help us, and we receive aid from various international Jewish organizations. I wouldn't want to bother my sons, their families, my grandchildren. Such are the times nowadays...