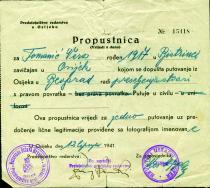

Vera Tomanic

Belgrade

Serbia

Interviewer: Klara Azulaj

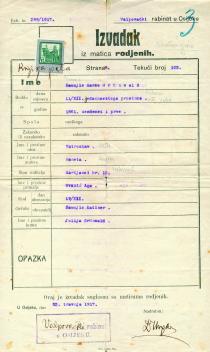

I was born in 1917 in Bistrinci, near Osijek, Croatia. My father, Pavao

Bluhm, was born in 1887 in Kiskoros, Hungary, and my mother, Elza Bluhm

(nee Grunwald), was born in 1895 in Bistrinci.

When I was born, we lived in Bistrinci, but we soon moved to Belisce, where

my father found work with the Jewish family Guttman, originally from

Hungary. That family bore the title of Baron. The Guttman family owned the

Slavonian-Podravian railroad, and they had a wood processing factory where

they also made tannin, a mixture exported to England for leather

processing.

The village of Belisce was an industrial area whose residents were all

workers and clerks employed by the Guttman family. We were given a

pleasant, spacious apartment. The problem was that it did not have its own

bathroom. In the entire settlement there was no plumbing, but they

installed special communal facilities, one for workers and one for clerks.

We had a small garden, which my mother took care of as a hobby, not out of

necessity. We had a servant for the household upkeep. At home we spoke

Croatian, Hungarian and German.

My father, Pavao, was very religious. Every morning he put on tefillin

(phylacteries) and prayed. My mother Elza was not religious to the same

degree, but our family marked all the Jewish holidays, and every Friday we

lit candles. We lived a real Jewish life because the Guttman family, which

was very religious, made it possible. Many Jews worked on the construction

of the railroad and in their factory. Besides my family, about 30 other

Jewish families lived in Belisce. We enjoyed a peaceful, harmonious life.

When it was time for me to start elementary school, I had to enroll in the

state school, because in Belisce there was no Jewish elementary school.

However, after school we had regular religion classes. Our teacher, Ankica

Stein, came twice a week from Osijek. So from a young age I was religiously

educated.

My father's parents, my grandfather Herman Bluhm and my grandmother Salli

Bluhm (whose maiden name I cannot remember), were Orthodox. They lived in

Kiskoros, Hungary. Grandfather Herman had two butcher shops: one kosher,

and one non-kosher. In their house, they kept kosher. My father's whole

family was very religious and strictly maintained all the religious

traditions. Grandfather and Grandmother Bluhm had seventeen children, but

not all of them survived. I remember six of my father's siblings: Ignac,

who was a clerk; Jocko and Feri, who were butchers; Miksa and Panni,

merchants; and Roza, a housewife. Unfortunately, only Jocko and Panni

survived World War Two. The others were killed in Auschwitz.

My aunt Panni married a merchant and remained in Kiskoros . We children

especially liked to go to her place, because she had a grocery store where,

among other things, she sold ice cream. Every summer we spent at least a

month with my father's family, and during the year, when it was convenient

for them, they came to visit us in Belisce.

Everyone in our family, from my mother's side and from my father's side,

were very close to one another. We liked to spend as much time together as

possible. And today, the few of us who survived get along very well.

My father's parents' home was a typical small village house. In the yard

they had cattle and poultry. As long as Grandfather Herman worked as a

butcher, Grandmother Salli took care of the house and raising the children.

Every Friday she took food to the bakery, and Saturdays she brought it back

so it would be warm, because on Saturday she would not light a fire.

My father finished elementary school in Kiskoros and continued his

schooling in Budapest at the Commercial Academy. Since his parents were

poor, during his schooling he ate with various Jewish families. When he was

not sure if the meat for lunch was kosher, he took a small piece and when

no one was looking he hid it in his handkerchief and later threw it away.

After finishing the Commercial Academy in 1915, my father went to Belisce

to work at the Guttman family's railroad. He got the work easily because he

spoke Hungarian and he was qualified. He started working as the director of

a sector. Father only learned Croatian in Belisce. My mother Elza lived in

Bistrinci, literally the neighborhood next to Belisce. Through fortunate

circumstances, Mother and Father met and married in 1916.

My mother's parents, Marko Grunwald and Eleonora Grunwald (nee Spiezer)

regularly went to synagogue and observed all the holidays, but Grandmother

Eleonora did not keep a kosher kitchen. Grandmother and Grandfather had

three children, Elza, Berta and Felix. Grandfather Marko was born in 1861

in Marijanci, near Osijek. In Bistrinci he had a mixed-good store. He died

in 1917. Grandmother Eleonora was born in 1871 in Barcs, Hungary. When she

married my grandfather, she helped him run the store. After his death, she

moved, with her daughter Berta, to our apartment.

Her youngest child, my uncle Felix, enlisted in the army in Bistrinci in

1915 while still a minor. When he understood that this had been a mistake,

he deserted, and went by boat to America. There he trained to be a butcher

and opened a butcher shop. In 1935, for the first time after deserting, he

came to visit his family again. I remember how harshly he criticized the

way our butcher shops processed poultry. After America, the work here

looked crude. He died in Cleveland in 1954.

Because of my enrollment in the gymnasium, my family moved to Osijek in

1929. I enrolled in the women's gymnasium. It was not a Jewish school, but

at the time I started there the director was a Mr. Herschl, and many of the

teachers were Jewish. I remember Professor Polak, and the German teacher,

Mrs. Fischer. As soon as we got to Osijek, I joined the Jewish youth there.

My parents bought a house at 18 Zagreb Street, and my mother opened a shop

which sold food out of our home. She had two salespeople, and she herself

worked the cash register. My grandmother Eleonora and my aunt Berta, who

continued to live with us even after we moved to Osijek, took care of my

younger sister Lilie, who was born in 1923, and me.

In 1930, together with his Jewish friend Miroslav Adler, my father opened a

big textile store that sold fabric by the meter. It was on the street with

the most traffic. In the store were four full-time, permanent employees,

and one cashier.

Around 2,000 Jews lived in Osijek. There were two synagogues, one in the

upper part of the city and the other in the lower part. We had our own

rabbi, cantor and shochet (kosher butcher). The rabbi was Dr. Ungar, a very

well-educated man. The temple was well-attended, big and beautiful. Every

Friday night, even the young people would go to the temple. No one forced

us to go, it was in our upbringing, and out of our own personal need.

In addition to the temple we had a place for socializing, performances and

lectures. The Jewish community was big, very active and religious. I

remember Hana Levi, who worked in the Osijek elementary school. She was

brought from Israel to teach Hebrew to the children. In Osijek lived the

very well-known Dr. Weissman, who had a sanatorium. He was famous for the

fact that he treated the poor in Osijek free of charge, regardless of

whether they were Jews or not.

I became actively involved in Hashomer Hatzair. This was a left-leaning

Zionist group that supported the idea that Israel should be built based on

kibbutzim (collective settlements), without the need for force and weapons,

in a peaceful manner. Our goal was to go to Israel one day and cultivate

the land. We had good instructors. Among the first settlers in Israel were

Jews from Osijek.

The most active members of Hashomer Hatzair were Ruzica and Josha Indig,

Zora and Zlata Glid, and Heda Maller. Many of the members went to Israel,

and there they established Kibbutz Shaar Hamakir, which still exists today.

Later on, they established Kibbutz Gat. At the meetings we received

information about what was happening in Israel and about the Zionist

movement. My group was called Kadima and many girls from it went to Israel.

I remember Lea Rosezweig , Mira Maller, Hilda Goltlieb, Magda Beitl, Zlata

Stein. There were 50 or 60 girls and boys in Hashomer Hatzair. My younger

sister Lilie was also active. Every summer we went on a joint summer

holiday. There was Vico, the women's Zionist society, which raised money to

buy land from the Arabs and to open hospitals and old age homes in Israel.

Saturdays at 11 there were special services for the youth held by a Dr.

Freiberger. The Jews helped one another a lot, especially the rich helped

the poor. Many children from elsewhere went to school in Osijek. Since

there was no organized cafeteria, these children ate with Jewish families.

One boy came to my house every day for lunch.

After finishing gymnasium, for health reasons I did not continue with my

studies. I intended to later, but my life story took another direction. I

met my future husband, Milorad Tomanic, and because of him I neither went

to Israel nor continued my studies.

Milorad was an active officer in the Yugoslav army stationed in Osijek when

we met. He was only granted permission to marry once he became a

lieutenant, so the two of us dated for four years. In the beginning, my

parents were not thrilled that I was dating a non-Jew, but over time they

learned to like him and we married in 1939. He grew very close to my

parents and they saw that he honored and had a positive attitude towards

Judaism. He was so tolerant that we celebrated all Jewish holidays in my

house. Our children and even our grandchildren were brought up to be proud

of the fact that they are Jews, and he supported me in this.

For professional reasons my husband had to move to Belgrade and enroll in

Faculty of Mechanics; these studies were financed by the state. Upon

arriving in Belgrade, I gradually made new friends. In the beginning I

socialized only with the family of Regina Alfandari and with my mother's

distant relative, Aunt Olga. With regular visits to the synagogue, which

was on Kosmaj Street, my circle of friends grew to include the Krauss and

Kresic families.

In the beginning we lived as tenants. My parents helped us a lot

financially, and we had my husband's stipend. We frequently went to Osijek

for the weekend to visit my family, because I missed them very much, and my

sister Lilie often came to visit us.

1941 arrived and one could simply feel in the air that something terrible

was stirring. Fear grew in Jewish circles as news arrived about the events

throughout Europe. People still hoped that nothing would happen. My husband

abandoned his studies because he was mobilized, and I remained alone in my

seventh month of pregnancy. On April 6th, Belgrade was bombed. Regina

Anfandari's family arrived to help me. They took me to their apartment.

Together we decided to leave Belgrade. We started off towards Kaludjerica

on foot, but after two days we all returned to our own apartments. Belgrade

was full of debris, and on April 9, 1941, I resolved to make my way back to

Osijek to my parents.

My mother fainted when I appeared at the door, because until then they

didn't know what had happened to me. They had only heard about the bombing.

They told me that the same day, the Independent State of Croatia had been

declared. The next day, news arrived that the synagogue in Osijek had been

burned. We were all shocked and we no longer went out on the street. My

father did not open his shop. Every day, new limitations on Jews were

announced: forbidding our movement, instituting a curfew, confiscating

shops, banning us from using public transportation. We could not even go to

the vegetable market in the morning, but only just before it closed. A new

Jewish community was formed and we all had to register. In the community

they gave us a little bit of help in the form of food.

On July 10, 1941, the first 50 Jews and the first 50 Serbs were arrested.

We Jews each received a yellow armband with numbers, and a little Star of

David which we had to wear on our arms. In some respects, the Croatian

Ustache (a political and military organization of Croatian nationalists

before and during World War Two who supported the Nazis) were worse than

the Germans.

On July 2, 1941 I gave birth to my daughter Mirjana. I was in the hospital

when they announced that Slavko Kvaternik (a Croatian politician and

nationalist during World War Two, who was declared a war criminal after the

war) would arrive in Osijek over the weekend. A decree stated that from 11

on Saturday to 11 on Sunday, Jews and Serbs were not permitted to appear on

the streets. A big rally was supposed to be held.

I asked the doctor to let me go home, because I did not want to be

separated from my parents. They let me go. At the rally, they carried

coffins and burned Jewish books, while yelling anti-Jewish slogans. After a

few days, a group of Ustache raided our house with the intent of taking

anything they wanted from it. My mother recognized one of them and

courageously told him: "Can't you see that this woman just gave birth to a

baby? Are you going to take the bed she is lying on, too?" As if she could

feel something terrible happening, my baby began to cry with all her might.

The one that my mother recognized flew out of the room and screamed to the

others: "Can't you hear how that baby is crying? Let's get out of here."

And they collected themselves and left. So we were saved, but from the

great fear I lost my milk and was no longer able to breastfeed my baby.

Soon a decree came that several Jewish families would need to live

together, and a Ms. Papo came to live with us.

In the village of Tenja, Jewish youth began building a camp for Jews.

Osijek Jews were expected to come up with 2 million dinars for security

that nothing would happen to them. They were barely able to collect this

money. The youth built barracks in the Tenja camp where we were supposed to

live, as if to await the end of the war in peace.

Returning from work one day, our youth ran into a group of German youth and

it quickly came to a brawl. Kalman Weiss, a boxer, was in our group. He had

an iron fist and he beat a number of Germans, so they ran away. We knew

that there would be retaliation for this incident. All of our group decided

that we would illegally leave Osijek.

They especially wanted Kalman. They caught him, but he jumped out of the

truck where they had put him and ran away.

In the meantime the camp in Djakovo was constructed, especially for women

and children. The women from Vinkovac, Slavonski Brod and Vukovar were

taken there. The first two months the Osijek Jewish community provided food

for the camp. The Ustache government allowed each family to take one child

from the camp and take care of him. My family took care of a 12-year-old

boy whose name I cannot remember, and a 4-year-old girl named Zuza from

Vinkovac, whose mother remained in the Djakovo camp and whose father, we

found out later, was killed in Auschwitz. It was clear to everyone that

there was no future for Jews, and many tried to flee to Dalmatia. My father

wanted us to try and reach Hungary, but my mother Elza began to panic

because she feared we would not have anything to live on there. Grandmother

Eleonora said that she was too old and could not run, and Aunt Berta did

not want to go without her mother.

From April 10, 1941 to May 15, 1942, I illegally went to Belgrade a few

times, with permission slips written under another name. I went to check on

my apartment and to see if there was any news from my husband. And I tried

to find something to do because I did not have any income.

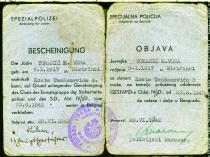

In Serbia they issued a law that Jewish women would not be taken to camps,

so I managed to get documents from the Germans that I could continue to

live in Belgrade. However, they did not give me documents for my child. On

the 15th of May 1942 I stayed to live in Belgrade. After my departure, my

parents tried to flee. They paid a local German named Rot to smuggle them

to Hungary. Rot turned out to be a swindler, and instead of sending them,

he handed them over to the Ustache police.

Rot survived the war, and my sister Lilie and I testified against him in

1945. However, he managed to run away and escape the trial.

In June, 1942, my parents, my aunt, and my grandmother were taken to the

Tenja camp. In the camp were about three and a half thousand people. From

Tenja they were sent to Auschwitz. My father was taken to the Jasenovac

camp and my mother to the Stara Gradiska camp, while Grandmother Eleonora

and Aunt Berta were kept in Auschwitz. None of them returned.

In the meantime I learned that my sister had managed to get to Budapest.

The grandmother of little Zuza, the girl who was staying with my family,

sent a man to smuggle her granddaughter and my sister across the Danube on

a small boat to Subotica, Hungary, where she herself lived. The escape

succeeded. My sister awaited liberation in Budapest, living under the name

Magda Sipos. This identity was obtained for her by our father's distant

relatives, with whom she made contact in Budapest.

I lived under very difficult conditions in Belgrade. I survived by selling

things from my apartment. Officially, I received 200 grams of corn bread,

and that was only under my name since my daughter Mirjana did not have

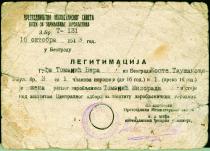

documents. Later I was able to regulate all of my documents on account of

the fact that my husband, Milorad Tomanic, was an active military officer

in captivity. At that point I fell under the protection of the Red Cross.

My husband regularly contacted me from captivity. He changed camps many

times. Among those camps were Nuremberg and Osnabrueck. In Osnsabrueck

there were two camps one next to the other. One was for officers and the

other for communists and Jews. Some of my relatives were in the other one.

Since my husband was able to receive packages, for Purim I made kindle,

which he smuggled in to my cousin Mark Spiezer and to his brother who was

imprisoned as a communist in the other camp. Through my husband, I kept in

touch with them and with my sister Lilie. She wrote to him, and he sent me

news about her, and her, news about me.

1945 arrived, and with it, liberation. Now I needed to be patient to see

who would return. I was sure that my aunt Berta, who was very beautiful,

had survived. I knew that the Germans had houses for their entertainment. I

thought that maybe she had reached one of those houses and in that manner

would have been saved, but she did not. She was killed in 1942 in

Auschwitz.

I did not have the patience to wait for news from my sister, so I left my

daughter with my cousin Olga, and went to Subotica where there was a

reception camp for those that had returned from Hungary. They were unable

to give me any information, and I went towards Budapest with two Jews who

had returned from forced labor in the Bor copper mines and had family in

Hungary. We started off in a truck driven by a Russian who agreed to take

us for free. On the way I bought food and other necessities for my sister.

In Budapest I inquired at the military mission and received information

about my sister. You can imagine how excited we were to see one another.

However, she was unable to return immediately with me. She had to wait for

a regular transport so that she could receive the necessary documents. I

returned to Belgrade. On May 1st my sister and her good friend Vilma

arrived. They stayed with me in my apartment. Very quickly I found work,

and soon my husband arrived from captivity. The first thing my child said

when she saw her father was: "This is my father from the picture." While

the other members of the household worked outside the house, I became a

classic housewife. I cooked and cleaned for all of us. Soon Lilie and Vilma

moved out and got married, Lilie to a Jew named Djordje Alpar, Vilma to a

Serb. My husband was employed by the military, because while he was in the

camp he was active in anti-fascist work.

After liberation I was very active in the women's anti-fascist movement. In

1945 in the journal Politika there was an ad asking Jews who survived the

war to register. I immediately registered and began helping in the

community, forming a kitchen and a reception center. We cooked and did

laundry for those who returned from various camps and from the Bor mines.

Life returned to some sort of normalcy. In 1948 I gave birth to a son,

Rodoljub. However, my brother-in-law Djordje Alpar was arrested as a

follower of Stalin (editor's note: Tito and Stalin had their famous falling

out in 1948 and Yugoslavs turned to those who seemed to side with the

Soviets). My husband and I took care of my sister and her daughter up to

the moment when they arrested my husband. They imprisoned him because he

was a follower of Cominform, a political organization of the communist

countries, under the control of the USSR; and also because he believed that

Tito and Yugoslavia should accept all of Stalin's positions. To make

matters worse, my husband stated at a meeting that the construction of Novi

Belgrade could not be completed as established in the first five-year plan.

He was an engineer by profession and he knew the terrain on which they were

building Novi Belgrade. It was sandy and needed a lot of preliminary work.

He also complained that the government was confiscating wheat from the

peasants. One of his biggest sins was that he did not denounce his brother-

in-law Alpar when they charged him, and moreover, he took care of Alpar's

daughter and wife. They gave him a three year prison sentence.

Again my sister Lilie and I lived without means. Luckily some distant

relatives from Israel sent us packages, so we were able to survive by

selling the things from these packages: chewing gum, combs. My husband was

released in 1954. I became active in the work of the women's section of the

Jewish community. Still, I mostly concerned myself with taking care of my

family. I educated my two children. Now my daughter Mirjana is a doctor and

my son Rodoljub is an engineer. Unfortunately, my husband Milorad died in

1998.

Now I am already very old. I do not often go to the Jewish community, but I

raised my children and my grandchildren in a Jewish spirit and they

continue on in the way that I showed them.

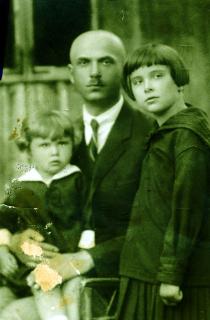

![Vera Tomanic's aunt Berta Grimberger [ nee Grunwald] Vera Tomanic's aunt Berta Grimberger [ nee Grunwald]](/sites/default/files/styles/width_210x_fallback/public/photo/orig/Bluhm05.jpg?itok=2EJ7hbwu)