Vera Burdenko

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: April 2002

My family background

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

My father Ierahmil Korolik was born into a very rich family in Kiev in 1898. His father Morduh Korolik was a merchant of Guild I 1. He was born in Kiev around 1865. My grandmother's maiden name was Golda Gorodetskaya. She was born in 1872. I don't know her place of birth. My grandfather and grandmother lived in the center of Kiev. They were not subject to the residential restrictions that had an impact on other Jewish people in tsarist Russia [see Jewish Pale of Settlement] 2. I don't know what kind of business my great-grandfather was involved in. I believe that he was in the same business that his son was, and his son must have inherited this business from him.

Grandfather Morduh had many houses that were on lease. I don't know exactly how many he had or their location but I remember my father and I passing some big houses and my father telling me that those had been my grandfather's before the [Russian] Revolution of 1917 3. They were one-storied, but they seemed huge to me, perhaps because I was small then. The family lived in one of those houses before the Revolution. I don't know how many rooms they had, but from what my father told me they lived quite a luxurious life. They had expensive furniture in their apartment, a grand piano, crystal chandeliers, velvet curtains and cozy sofas. This was a rich home of a respected man.

My grandfather was a very religious man: he observed all Jewish traditions and said his prayers. They followed the kashrut and celebrated Sabbath - my grandfather came home early on Friday and my grandmother lit the candles. They weren't even allowed to strike a match on Saturday, therefore the festive dinner was cooked and served by housemaids. However, they had housemaids anyway, and my grandmother didn't bother herself with the cooking or cleaning of the house. Of course, she handled and supervised the housekeeping. My grandmother gave all necessary products to the cook herself.

They led a luxurious way of life. My grandmother went to fashionable shops; she dressed beautifully and was quite unlike the Orthodox matrons in their shawls and wigs. She had fashionable hats and capes, jewelry and fur coats. She wasn't as religious as my grandfather Morduh. She didn't pray every day, but all Jewish traditions were to be observed in the house. She wanted to support her husband in his belief. My grandfather had all religious accessories at home: tallit, tefillin and the Talmud. After my grandfather died in the early 1930s my father kept his tallit in a drawer of his desk. We, children, had no idea what it was and asked my father permission to borrow it for one of our games. My father, however kind and nice, strictly forbade us to take it.

My grandfather Morduh made a significant contribution to the development of the Jewish community in Kiev. He provided money for the building of a synagogue, which is located in the area that belongs to the Transsignal Plant today. During the Soviet power it became another facility at the plant, but it was returned to the Jewish community in 2001. That's the synagogue that was built by my grandfather and I'm pleased to know that.

My grandfather and grandmother Korolik had two children: my father and his younger sister Esphir, born around 1902. I only have one picture of her when she was a child. Esphir was married to a famous obstetrician in Kiev. His last name was Medovar. They had no children. When the war began her husband was recruited to the army. Esphir went into evacuation. She had a heart attack on the train and died in August 1941.

My father finished school and led a very secular way of life. He was a fashionable young man. He wrote poems and was fond of theater and music and free from any responsibilities or obligations.

The Revolution put an end to this luxurious way of life in 1917. The Bolsheviks expropriated all real estate of the family, leaving them to live in a small house. They took away all valuables: silver, jewelry, gold and their savings. After the Revolution my grandparents lived in a two-storied wooden house on Kerosinnaya Street. We often visited them when I was a child. I remember a small garden near the house where we used to play. My grandparents lived on the second floor of the house and when we went upstairs we could already smell the delicious food that my grandmother was cooking for us. I remember little triangle pies with poppy seeds that my grandmother made for Purim. I didn't know the name of this holiday back then but I remember how delicious and joyful it was. At Chanukkah we, kids, always got some money and sweets, and there were always doughnuts and potato pancakes on the table. Well, my grandfather's house is associated with the smell of doughnuts to me. There was stuffed fish, chicken broth and stuffed chicken and many other delicacies on the table.

I don't know how my grandparents made their living after the Revolution. I believe my grandfather managed to save some valuables from being expropriated. They led a modest but fairly good life. After my grandfather died in 1932 my grandmother Golda lived with us for some time and then she moved to her cousin. I don't know whether my grandmother followed any traditions at the end of her life, but she wasn't fanatically religious anyway. I guess she went to the synagogue, although I'm not sure about it. But she probably observed the high holidays, such as Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. She died in 1946 in evacuation in the Middle East.

My mother Evgenia Welkomirskaya was born in 1888. She was born in Poland, but where exactly I don't know.

My grandfather's name was Wazlav Welkomirskiy. He was born around 1860. He may have been given a Jewish name when he was born, but they lived in Poland and he probably changed it. I have no information about his education. It must have been some technical or some kind of higher education because he worked at the railcar shops as a skilled worker and then as an engineer in Kiev. They moved to Kiev long before World War I, some time around 1900. I don't know why they moved. My grandfather received an award from the Russian government. It was a beautiful red ribbon and the words 'Hero of Labor' were written on it. He was awarded it in the first years after the Revolution. My grandmother's name was Welkomirskaya. I don't know her first and maiden name. I know very little about my grandparents on my mother's side. They died before I was born. I guess, they died in the early 1920s. The Welkomirskiy family wasn't religious. At least, I can't remember my mother ever telling me about any religious traditions in their family.

My mother was their only daughter. Her parents weren't rich but she received a good education. She finished a grammar school in Kiev, located on Fundukleyevskaya Street in the center of Kiev. Later this street was called Lenin Street and now it is Bogdan Khmelnitskiy Street. My mother became a private teacher in rich families when she was young and worked as a governess in the summertime when the rich left the city for their country houses. I have a picture of my mother at the time when she was working for one of those families. At the same time my mother studied in a private music school.

After finishing school she went to St. Petersburg Conservatory, passed all the exams and received a diploma of the Petersburg Conservatory signed by Ilia Glazunov [a famous Russian pianist and composer]. This diploma gave my mother the right to teach music. She returned to Kiev and began to give private music classes. She was invited to the house of my father - to teach him and his sister music. My father was much younger than his music teacher but he fell in love with her immediately. He kept silent for several years, although my mother understood that her student wasn't indifferent to her. When he told her of his love she got scared and left, refusing to teach him music any more.

My father told his parents that he couldn't live without Evgenia and asked their permission to marry her. Of course, they were against it. Firstly, my mother was ten years older than my father; an age difference which wasn't quite typical in Jewish families. Secondly, she came from a lower class of society. My father had a big argument with his parents. The result was that he took his razor, underwear and a book of poems and came to my mother. They were living together, which was against any moral principles of society. Their first baby was a boy. He didn't even reach the age of one. He died approximately in 1920. Later my parents had a civil ceremony and only after that they were allowed to visit their parents. My father could never forgive his parents that they didn't accept my mother. They did accept her later, but my husband couldn't forget that they were dead against their marriage.

My father had no education besides school, and my mother insisted that he entered a higher educational institute. He entered the extramural department of Kiev Engineering and Construction Institute. He worked as a foreman and then engineer on a construction site even before he finished his studies at this institute. My father always came home late and was very tired. I remember my mother telling us not to bother him because he had to do his homework. But my father always found some time to spend with us. He was very fond of his children. Upon graduation my father went to work at a plant and then at the Ministry of Construction. My mother was teaching music privately and that was what our family lived on.

I was born in Kiev in 1925 and was the oldest of the children. My sister Lilia was born in 1929. She was born a weak and sickly girl. She got ill with tuberculosis when she was three years old. It was lung and kidney and osseous tuberculosis. She couldn't walk for a few years. She was confined to bed. I loved her a lot and spent lots of time with her. I read books to her when my mother went to her classes. Lilia learned to read when she was very young and was reading too much. Reading had an impact on her sight. In 1932 my mother had twins - Anna and Tamara, but we called them Asia and Tasia at home. My mother was 45 and she wanted no more children. But abortions weren't allowed at that time and my mother had no option. Our life was very poor and miserable then. I remember we kept potatoes under the grand piano - it was the only dry spot in the apartment. My mother made potato soup and some second course dish - this was our main food. Once Lilia and I took out a couple of potatoes and ate them raw while waiting for our mother.

I started school in 1933. It was an ordinary Russian secondary school. There were children of many nationalities, including Jewish children, who studied there. There was no issue of nationality then - we were all Soviet children and we were all equal. I was a poor pupil. I mostly got grade '3' - out of the '5' grade system. I took no interest in mathematics or physics and these subjects were very difficult. However, I read a lot and knew Russian literature well.

My biggest hobby was music. My mother taught music to me and Lilia. Lilia recovered and went to the same school where I studied. Our family was rather poor. I remember my mother giving us jam sandwiches for lunch at school. I was ashamed of these sandwiches. Many other children had sandwiches with fish, sausage or cheese. I tried to eat my sandwiches when nobody could see me. If there were children around, I would suffer from hunger and never take my 'poor' sandwiches out of my bag, so that nobody would see them. Lilia took such things easy and enjoyed eating everything that my mother gave us. She managed to exchange her sandwich for something more delicious. In exchange she solved problems in mathematics or wrote compositions for other children.

We lived in a big four-bedroom apartment on Tarasovskaya Street in the center of Kiev. This was the apartment of my mother's parents. Later the authorities gave two rooms to two young workers that came from provincial areas. I remember them well - the two young girls in red shawls. The apartment was furnished with pre-revolutionary furniture that belonged to my mother's parents. There were two instruments: my mother's piano, which she had had since her childhood, and the grand piano, a gift of Morduh, my father's father.

We had a big kitchen and my mother cooked on the Primus stove. We didn't have a bathroom and the family went to the sauna twice a week. We had a housemaid because my mother couldn't handle the housekeeping just by herself. The housemaid was a common Ukrainian woman. She came to Kiev in 1933, during the famine 4, and stayed with us. She slept on the sofa in the living room and my parents and the four of us, children, slept in our bedroom.

In summer we often went to the village where Glasha - this was our nanny's name - lived. My mother spent a lot of time with us: she taught us music and French. We had a rule: we had to speak French on certain days and the one who broke this rule had to learn a poem or a fable by heart and recite it. We went for walks in the Botanical Gardens not far from our house or to the railway station. At that time it was a usual thing to go for a walk to the railway station.

My father was working a lot. He was a real Soviet man. He became a member of the Communist Party in the early 1930s. He believed in the five-year plan 5 and in socialism and communism and he used to convince us even in the most difficult years that those were temporary difficulties in our country and that everything would be fine some day. My parents' friends often came to our home. We celebrated 1st May and October Revolution Day 6. Everybody enjoyed these holidays, we danced and sang Soviet songs.

We spoke Russian at home. We didn't celebrated any traditional Jewish holidays. We only heard Yiddish when we visited our grandparents. They always celebrated Jewish holidays and my father used to take us to his parents especially for the holidays. I cannot say exactly what kind of holidays they celebrated, nobody told us anything about them, about their history. They must have been afraid that we might mention it at school and cause problems, of course, because in the 1930s religion was already persecuted by the authorities [see struggle against religion] 7. We started getting this information about the past only recently, in the 1990s. I believe the celebrations were at Chanukkah, Purim, Rosh Hashanah, and we, kids, always got money and sweets. My mother hardly ever visited my paternal grandparents. She always remembered that she had been rejected by her husband's parents. We had many books at home. My grandfather gave his collection of books to my father and my father added new books to it. There were books by Russian and Jewish writers and international classics, all in Russian. My parents led an ordinary life of the Soviet intelligentsia.

Everything went fine until unjustified arrests and repression began in the late 1930s [during the so-called Great Terror] 8. We, children, didn't quite understand what was happening. We saw that our parents were upset and depressed. My father often came home from work looking pale and lost. My parents went to the room and closed the door behind them. They used to talk for a long time. Later we got to know that one of my father's closest friends had been executed. My father was called to the NKVD 9. They forbade him to help his friend's family. But he did support them. And he did it openly. It was difficult because my father's salary was very small. And the money that my mother made was a modest support of our family budget. Often we had nothing left before the next pay day. This support that my father decided to provide was dangerous and also hard from a material point of view. But my father thought it was a question of honor and he openly visited his friend's wife and helped her as much as he could.

These people were our neighbors. Once we, children, started teasing the children of this man that was executed. We didn't quite understand what we were doing. My father hit me for the first time in my life. He said I was the oldest and was supposed to understand how mean it was on our part. We never did it again. Every day my father was saying goodbye to my mother before going to work, because he didn't know whether or not he would be back. It was especially frightening at nighttime. They used to arrest people at night. However, providence must have protected my father. My mother's cousin was arrested. He was an actor. His stage name was Kardiani and that was the only name that I knew him by. He probably said something politically incorrect and was arrested right on the stage. Nobody ever saw him again. In the middle of the 1950s his children received documents confirming his rehabilitation 10 and his death certificate. He died in one of Stalin's camps [see Gulag] 11.

The war was a complete surprise for us. I remember 22nd June 1941, the first day of the [Great Patriotic] War 12. We were wondering what a war was like and what was ahead of us. My father was sure that the war would be over within a few weeks and that Kiev wouldn't be left by our army and that there was nothing to worry about. Nobody in our family ever spoke about Hitler exterminating the Jewish population. I think my parents forgot that they were Jews. In the middle of July Jews from Western Ukraine appeared in the Botanical Gardens: children, old people and women. They lived in the open air, tents or on the ground. They presented a horrible sight. They were telling people the truth about the extermination of Jewish people by Germans. Then the Minister of Construction, my father's boss, called my father. He told him to get ready and leave with the family.

We went to the railway station on a horse-drawn cart. Asia and Tasia were enjoying themselves. They found everything interesting. But Lilia and I seemed to begin to understand that a war was no game and that we were to go through a hard time. Still, the reality turned out to be much more frightening than any of our childish concerns. We were going by train. We were in lack of food and water. My father got off the train when it stopped to look for some food. We were giving away anything we could in exchange for food.

At first we lived in the village of Korzovo, Kuibyshev region. It was a distant village and we lived in a house that had been deserted by its former tenants. My father went to work on a collective farm 13. My mother and I planted some vegetables in the garden. Although it was already summer we hoped that we would be able to do some harvesting. The collective farm gave my father a piglet to breed and slaughter afterwards. This piglet lived with us in the house. We called him Vaska. We gave him food and played with him. He was like a dog to us. He was very smart and nice. When the time came to slaughter him we all cried so hard that the adults had to take him to the neighbor's yard to slaughter. We cried for a long time remembering our Vaska. We refused to eat the meat and sausage and our parents had to sell these products or exchange them for other food products. I have horrible memories of the evacuation. It was destitution and starvation all along. This was life full of search for food and hard work.

Later, in 1943, my father was called to join the labor front and he left for Kuibyshev. We joined him some time later. We lived in a big house in Kuibyshev. My father worked at a military plant. My mother was constantly doing different work to earn a little. She gave music lessons or did the washing and cleaning for richer families. I finished school. My younger sisters also studied. But Lilia fell ill with osseous tuberculosis. She was confined to bed again. While staying in bed she learned to sew and made clothes for me and my little sisters. She was very good at it. She could make a nice dress or skirt from a little piece of fabric. She could even make beautiful hats. After the war we wore what Lilia was making us for a long time. Lilia had to stay in bed for almost two years, until the time when we had to return to Kiev.

We returned to Kiev immediately after the war was over. It took my father some time to obtain a request from his workplace and permits for the members of his family. It was necessary to have the relevant documents and permits to be able to go back home from evacuation [see residence permit] 14. When we returned to Kiev Kreschatik [the main street of Kiev] was in ruins. Many buildings in Kiev were ruined. Our apartment on Tarasovskaya Street was occupied. Our furniture and what was even more important - our piano and grand piano - were in this apartment. My mother couldn't work without her instruments. We had to get them back. My parents had to appeal in court for what was theirs. In a few years' time my father received an apartment in a new building on Tverskaya Street, where I live to this day. My sisters and me continued to study in school.

I entered Kiev Music School. After finishing it I entered the flute department at the Conservatory. Lilia studied at the conducting/choir department of Kiev Music School. She met Igor Ivaschenko, a nice, young Ukrainian man, and married him in 1949. All of us lived in this three-bedroom apartment on Tverskaya Street: my parents, Lilia, her husband and their daughter Irina, born in 1951, Asia, Tasia and I. My bed was in the bathroom for quite some time - our bathroom was a big room - and we used to look at things with a sense of humor. We always had guests at home. My younger sisters' friends used to visit them right after their classes were over, conservatory students used to come by and we all enjoyed ourselves and felt comfortable, although our living conditions were always rather difficult. Later Tasia entered Kishinyov Conservatory. It became more and more difficult for a Jew to enter higher educational institutions or find a job.

I need to say that my family didn't face any problems associated with the anti-Semitism of the late 1940s - early 1950s. I remember my father having some problems at work but things must have come to a quite satisfactory solution. The persecution of Jewish lecturers began at the Conservatory. Many of them were dismissed and many had to move to Siberia, to the North or to smaller towns because they couldn't find a job in Kiev. However, students weren't involved somehow and these processes went past us.

I faced anti-Semitism only when I was obtaining my [mandatory] job assignment 15. I had a request from Kiev Opera House sent to the Conservatory asking them to issue a job assignment to me at the Opera House. But of course, because of my nationality the Conservatory assigned me to go to Donetsk. There were quite a few Jews in the Conservatory, talented violinists or pianists and they were all sent to smaller towns; not one of them could stay in Kiev. I was a 4th-year student when I married Yavorskiy, a music expert. He was a Jew and he was many years older than I. We didn't last a year together. His attitude towards me was fatherly and he patronized me even after we got divorced in 1950. He was very well-known in the Kiev musical circles but even he couldn't help me to stay in Kiev.

I worked at Donetsk Opera House for three years. In 1953 Stalin died. There was a meeting in the concert hall and the actors went onstage to hold a speech, and they cried and each of them said that we had lost 'our father', etc. My friend and I were sitting in the audience. And all of a sudden we burst out laughing. It must have been either out of nervousness or because we just couldn't bear the hypocrisy of it all. The master of ceremony came to reprimand us. He threatened that they would ask us to leave the ceremony. So we had to calm down. We were afraid that they might dismiss or arrest us afterwards.

In Donetsk I met Lekov, the choreographer of Donetsk Opera House. He was a handsome man and women adored him. I fell head over heels in love with him. We lived together and I came to Kiev when I was pregnant. Lekov came with me and we settled down at my father's place. Lekov got employed by Kiev Opera House and was chief choreographer there for some time. He treated me nicely for a while. Then he got loose and fell for another woman. It was all so scandalous. My family just told him to get lost.

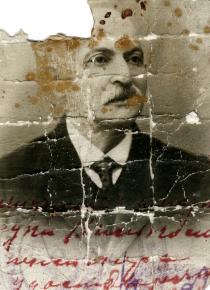

Lilia was very sympathetic and stayed with me all this time. A few weeks later I gave birth to my son. This was in 1955. I was single - Lekov and I never got married - and we gave Zhenia my father's last name; and the patronymic accordingly: Evgeniy Mikhailovich Korolik. My mother died in 1956. (Photo 7) Our apartment was empty by then. Igor Ivaschenko was offered a job with the Virskiy Folk Dance Group. Igor was a very talented pianist and conductor and he was very popular with employers. All kinds of groups tried to employ him. But Virskiy gave him a room and then, in a year's time a good two-bedroom apartment.

Asia and Tasia got married in due time. My father, my son and I stayed in the apartment on Tverskaya Street. My father didn't remarry for ten years after my mother's death. He loved my mother and couldn't forget her. Besides, he felt responsible for me and my son. I didn't have a job and I was dependent on my father and Lilia. I must say that Lilia lived very well at that time. Her husband Igor went abroad on tours and they were very well-off. And she always remembered that her sister needed help. She always bought or made things double - one was always for Vera, me.

In order to cheer up a little I took to visiting the amateur Russian Folk Orchestra. I met a horn player there, Valeriy Burdenko, a Jew, and he fell in love with me. Valeriy was 14 years younger than me and grew up in a traditional Jewish family. His father was deeply religious. His whole family was religious. His parents were fasting at Yom Kippur. They cooked traditional food and observed Sabbath, went to the synagogue regularly and followed the kashrut. Valeriy was used to the Jewish way of life, but he wasn't religious himself.

Valeriy was an only son and his parents sincerely wished for him to be happy. And happiness suggested that all Jewish rules should be remembered: in religious Jewish families a wife had to be younger than her husband, hold a lower social position and education. She couldn't have been married before, or have a child. If she didn't meet all these requirements neither the parents nor a rabbi would have allowed such marriage. Of course, his parents were dead against our marriage. I, too, thought and told him that the differences made it impossible for us to be together. But Valeriy didn't give up. He visited me and he played with my son. He was so caring that I gave in. I also recalled that my mother was ten years younger than my father but that they loved each other so much and lived a long life with this love.

I married Valeriy and never once regretted it. He adopted my son and gave him his name. My son is called Evgeniy Valerievich Burdenko now. Our son Sasha was born in 1964. ???? We were an ordinary Soviet family and celebrated communist holidays and birthdays, visited relatives and friends. There was nothing related to the Jewish way of life in our life then. Sasha finished an ordinary Russian secondary school. There were no other schools in the Soviet Union then. Simultaneously he learned to play the piano at the music school. He was very gifted when it came to music. He tried to enter Leningrad Conservatory; we didn't even try to submit documents to Kiev Conservatory knowing its anti- Semitic atmosphere. It turned out to be no easier in Leningrad. My son successfully passed all his exams in his category, but got a '3' in the history of the Party. Sasha went to the army and then entered Kiev Conservatory and finished it.

Sasha and his Jewish wife - she too is a musician - moved to Germany. He lives in the vicinity of Munich, he is a recognized musician, he published records and CDs and he has students, too. His son Yuliy was born in 1998. My older son Evgeniy lives in Kiev. He and Valeriy opened a car company. His wife Zhenia and he have two children: their son Kirill, born in 1986 and their daughter Daria, born in 1989. So, I'm a happy wife, mother and grandmother.

My father got married for a second time in 1966 after I got my life under control. He went to live with his wife Maria Lvovna, a Jew. They lived together for six years until his death in 1972.

My sister Lilia divorced Igor Ivaschenko when their daughter Irina was ten years old. Later Lilia married a musician ten years her junior, and her daughter Irina is eight years older than her husband. Therefore, it is our family tradition. However, all women in our family have been loved and cared for by their husbands. Lilia worked as a singer at Kiev Ukrainian Drama Theater for many years. In 1998 she died after terrible pain of cancer. Her daughter Irina lives in Kiev. She is a TV producer.

My younger sisters Asia and Tasia live in Israel. Tasia finished Kiev Radio Engineering College. She married Misha Markov, a Jew. They met at the plant where she used to work. They have two daughters: Maria, born in 1960 and Elena, born in 1964. They all moved to Israel in 1989. They left for the sake of Misha. He had a weak heart and needed a surgery that wasn't possible in our country. Although they were leaving at the time of perestroika 16, the departure was still a humiliating process when it came to resigning from work, obtaining all necessary documents and especially - at the moment of departure. The train was available five minutes before departure. Adults and children were crying and yelling, throwing their luggage through the windows. There was a disdainful behavior by the service personnel - this whole scene could only be compared with evacuation. But Asia's family went through it. Misha had a surgery in Israel. He worked many years before he retired. They got to love Israel; its religion and culture has become theirs. Misha became an active member of a party, but which party exactly I don't know, and takes part in the political and cultural life of Israel. They live in Ashdod.

Asia got educated at Kishinyov Conservatory and worked as a music teacher for some time. She married Alexei Reshetnichenko, a Ukrainian man. He was a sailor and worked as an engineer after his retirement. Asia and Alexei have a daughter, Tatiana, born in 1959. Tatiana was married to Miroslav Vishnevetskiy. They were friends since school. Miroslav was a very intelligent and energetic man, but he put all his energy into criminal business. As a result Miroslav disappeared - he was most likely murdered - and Tatiana and her two children had to escape from the country urgently. The criminals never left her alone: they demanded huge amounts of money and threatened to kill her and kidnap her children. And the only prompt way to escape was emigration to Israel. Asia, Tatiana and the children left for Israel in 1997. Alexei stayed in Kiev to arrange the sale of the apartment. But he died shortly afterwards - it must have been all the tension and nerves. Tasia waited for Miroslav several years, but then she married an Israelite when she understood that Miroslav wasn't among the living. Asia lives near Tatiana in Ashdod. She gives private lessons. She rings up her grandchildren.

So, it was destiny that the members of our assimilated family who didn't know Yiddish, Jewish religion, tradition or culture moved to Israel. . As for me, I returned to Jewish traditions some time before. My husband Valeriy grew up in a family that observed all Jewish traditions. At the beginning of our life together I tried to follow this way of life to please him. But in due time I understood that I was really drawn to my roots - the Jewish culture, language and traditions. We don't know Yiddish and don't know the holidays or traditions. We don't remember or don't have any idea about how to go about them. It's too late to start things now. We were raised as atheists and we still celebrate all Soviet holidays, although there is no USSR any more. But it's our life and we can't change anything about it.

I believe this is the way many Jews in this country lived their lives. But I'm interested and I'm trying to learn more about the Jewish culture. When my husband and I went to visit my sisters in Israel I felt that I stepped onto my motherland. I like Israel very much and if the children wanted to go there we would emigrate to this country. But Sasha is all right in Germany and Zhenia likes it in Ukraine. My husband and I try to be with our children: we live in Kiev and travel to Germany to visit Sasha. My husband and I went to the synagogue, founded by my grandfather Morduh, several times. I'm not a religious person but I was excited to enter this synagogue. It is wonderful that Jewish life has been restored in Ukraine and that we have Jewish newspapers, synagogues and cultural centers. I hope that our grandchildren will be closer to the Jewish way of life than we, children of the Soviet country.