Tsyliya Spivak

Kherson

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: September 2003

Tsyliya Spivak is not tall. She is a round lady with a short haircut making her look younger and independent. She lives in a big three-bedroom apartment in a 1970 house in a new district in Kherson. Tsyliya has a nice suit with trousers on. She looks well-groomed having her beautiful hands manicured and a touch of lipstick on her lips. She has shrewd eyes with a splashing smile in them and it seems that if it were not for her grief after her husband who died recently there would be plenty of humor in her story. Tsyliya’s apartment is nicely furnished with quite modern furniture. She has a Japanese TV set and a nice stove and microwave oven in the kitchen. Everything glitters with cleanness and careful maintenance, including the hostess radiating contentment and wealth.

My mother came from a big Jewish family living in Sednevo town in Chernigov province, 200 km from Kiev. I’ve never been to Sednevo, but my mother told me that it was like any other small Jewish town. There was a synagogue in the town. Jews commonly dealt in crafts and trade. My mother’s father Borukh Kaplan, my grandfather, was a tradesman. My grandfather was born in 1860 and received a traditional Jewish education: he finished cheder and a primary Jewish school and took to trading business. My grandmother Tsyvah, who was 12 years younger than my grandfather, was a housewife and looked after the children. Sometimes she helped my grandfather in the store in the house where the family lived. They didn’t have any other employees working for them in the store. They were selling haberdashery and household goods in their little store and Ukrainian customers of my grandfather from surrounding villages often came by my grandfather’s store to buy what they needed. My grandfather got along well with Ukrainians, but it didn’t help during the Civil War 1 when pogroms 2 and persecution of the Jewish population began. Our family, my mother in particular, suffered a lot from a pogrom made by a passing gang. My grandfather’s house and store were robbed and my grandfather was almost beaten to death and my grandfather decided to move to another place. In 1919 his big family moved to Chernigov [regional center in the north of Ukraine, 220 km from Kiev] after selling their remaining belongings.

In Chernigov my grandfather bought a small two-bedroom apartment in a private house where they lived until before the Great Patriotic War 3. My grandmother and grandfather were very religious people. My grandfather started every day with a prayer with his tefillin and tallit on and a kippah covering his head. He wore a cap to go out in autumn time and in winter he wore a fur hat. My grandmother always wore a kerchief or a lace shawl on holidays. They ate kosher food and celebrated Sabbath. The whole family got together on big religious Jewish holidays.

There were 12 children born to the family, but before the Great Patriotic War there were seven of them left. The rest of the children died in infancy and I don’t know their names. The oldest was my mother Nehama, born in 1895. Then came her sisters, one or two years younger than she: Bodana, Zelda, Sarrah and Sima and brothers Ziama and Yakov. It would be hard for me to tell their exact dates of birth and their sequence. Considering that the children only got primary education I can tell that the family of my grandfather Kaplan wasn’t wealthy. His sons studied in cheder and his daughters mainly studied with a visiting teacher at home: there was no Jewish school in Sednevo. Although all of the children received religious education the flow of time had its impact on them: after the revolution of 1917 4 they only celebrated holidays as tribute to Jewish traditions, but they gave up their faith following the trend of their time.

I shall start from my mother’s brothers. Ziama, approximately born in 1900, also dealt in trade. Before the revolution he was helping my grandfather and afterward he worked in a store. Ziama had a Jewish wife. Her name was Lisa and she was a housewife. Ziama and Lisa had two children: Boris, born in 1927, and Fania, born in 1932. During the Great Patriotic War Ziama was recruited to the army and perished at the front and Lisa and her children, our family and all sisters were in evacuation in Orsk in the Urals (today Russia), 3500 km from Kiev. They returned to Chernigov at the same time after the war. We were all poor after the war, but Lisa really lived in poverty. Shortly after he returned Boris fell ill and died of cancer in the early 1950s and Lisa lived a year or two longer. After Fania returned to Chernigov my mother’s sister Zelda who got married and left to the Far East with her husband, took her with them. Zelda actually raised Fania and helped her to enter a Pedagogical College. Fania married a Russian guy. Her surname is Kokina. She lives with her husband and daughter who has grown-up children in Tver, Russia.

My mother’s second brother Yakov was about eight years younger than Ziama. He worked as a tinsmith foreman in ‘Metallprom’ shop. Yakov had a wife named Basia and three sons: Mark, born in 1935, Vadim, born in 1937, and Felix, born in 1939. When the Great Patriotic War began, Yakov was on military training in a frontier harrison. He was wounded during the first bombardment and sent to the rear. After his stay in hospital he was demobilized and joined his family in evacuation. After Chernigov was liberated Yakov and his family returned home, but some time later they moved to Odessa 5 where my mother’s sister Sarrah lived at that time. Yakov died in the 1970s. Mark and his family live in Munich, Germany, Vadim lives in Moscow and Felix lives in Odessa. They finished Odessa Polytechnic College and have families, but we, regretfully, do not keep in touch.

Bodana was one or two years younger than my mother. Bodana was far from good looking and as a result she grew up uncultivated and unsociable. Young men avoided her and she didn’t marry for a long time. She gave up any hopes for personal life of a happy life as a woman. About 1938 a Jewish man came to work in the shop where Yakov worked. His name was Semyon Siganevich. For a long time he was working in this shop, but then he was put to jail for some misdemeanor and stayed in a camp for a few years. While he was serving his sentenced his wife divorced him and remarried and when Semyon returned he had nowhere to lay his head. Uncle Yakov said to him: ‘I will introduce you to my sister Bodana. She isn’t much to go for, but who knows…’ So they met and got married shortly afterward. They got along well and Semyon grew fond of plain Bodana and she returned his feelings. In 1940 43-year old Bodana gave birth to their daughter Fania and Fania’s parents just adored her. When the Great Patriotic War began Semyon was one of the first to go the war. He perished shortly afterward. Bodana and Fania were in evacuation in Orsk with us. After returning to Chernigov Bodana never remarried. She lived with grandmother Tsyvah after the war. Grandmother died in 1960, and Bodana died in 1980. Fania repeated her mother’s fate and didn’t get married for a long time. Around 1975 she visited us in Kherson and met my husband’s brother Yefim Spivak. They got married and Yefim moved to Fania in Chernigov. Their daughter Victoria was born there. A few years ago Victoria moved to Germany and then Fania and Yefim joined them there.

My mother’s second sister Sarrah was born around 1910. Sarrah was such a beauty that people stared at her in the streets. She finished an accounting course and worked as an assistant accountant. Sarrah married a Party official. His name was Ziama Aronov. Before the Great Patriotic War he was second secretary of the regional Communist Party committee. Sarrah and Ziama had a son named Alik. When the Great Patriotic War began Aronov was ordered to stay in Chernigov to organize a partisan unit. Sarrah and Alik evacuated to Orsk with the rest of the family. Many men were seeking Sarrah’s attention. Lev Troyanskiy, a man from Odessa, was very much in love with her, but Sarrah was faithful to her husband. Only after she returned to Chernigov and got to know for certain that Aronov had perished she agreed to marry Troyanskiy. Lev took her to Odessa. In Odessa Sarrah’s daughter Larisa was born. Alik served in the Navy and then finished a college. Larisa also got a higher education. Lev Troyanskiy died in the early 1990s and then his family moved to Germany. Alik and Larisa live in Munich. Sarrah died in 1998 in Munich.

My mother’s sister Zelda was much younger than my mother and Bodana. She was born around 1915. Zelda didn’t have a good education, but she was a Komsomol 6 member, trade union activist and held rather high public posts. Before the war Zelda met with Yakov Lifshitz, a nice Jewish guy. They loved each other very much, but they argued about some little thing and separated. Zelda married another Jewish guy to spite Yakov. His name was Yakov Shulman. They had a son named Roman. Zelda’s husband Yakov perished at the front. After finishing his college Yakov Lifshitz was sent to work at a military plant in Komsomolsk-on-the-Amur [over 7000 km from Kiev] in the Far East. After the war he found Zelda and convinced her to marry him. Yakov took Zelda and Roman to Komsomolsk-on-the-Amur. Besides Roman Zelda and Yakov raised Ziama’s daughter Fania and then my mother younger sister’s daughter Irina. After finishing school Roman entered Odessa Polytechnic College and after finishing it he received a job assignment to Kishinev. Aunt Zelda and her husband followed him there. Zelda died in 1982. Yakov didn’t remarry for a long time, but then he got married and moved to Israel. Roman and his family also live there.

My mother’s youngest sister Sima was born in 1917 when my grandmother was way in her forties. Sima loved my mother dearly and even sat on her lap during my mother’s wedding. Sima finished a 7-year school. She married Boris Shpektorov, a Jewish guy, and they had two daughters: Larisa and Irina. Boris perished at the front. Sima didn’t remarry. She died in 1998. Her older daughter Larisa finished a technical school and worked as an accountant. Larisa was married to Gennadiy Klyuchnikov, a Russian man. Her husband has passed away and her two sons moved elsewhere. Yevgeniy lives in Germany and Igor lives somewhere in Donetsk region. Larisa is alone in Chernigov. Zelda was raising her sister Irina. Irina and Fania finished a college in the Far East. Irina, her husband Yuri Sarayev, he is Russian, and their children Zoya and Boris live in Arsenyevo town in Primorskiy region, Russia.

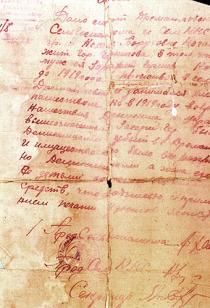

My mother Nehama Kaplan was the oldest of the sisters. My mother was almost as beautiful as her sister Sarrah. In 1918 my mother married Zachariy Kogan, a Jewish man. He came from Strezhalovka village. Regardless of hunger, devastation and pogroms they had a real Jewish wedding with a chuppah, music and feasting. My mother and her husband settled down in Grimaylov village with her husband’s distant relatives. Their son Aron was born there. During a Denikin troop attack 7 Zachariy was killed before his wife and son’s eyes and Denikin soldiers raped my mother. My mother kept an official paper saying: ‘This is issued by Grimaylov district executive committee to Nehama Boruchovna Kogan, resident of Chernigov town, to confirm that her husband Zachariy Gershevich Kogan resided in Strizhalovka village before 1917 dealing in farming. However, in 1919 during Denikin invasion to Ukraine, the above mentioned Zachariy Gershkovich was killed by Denikin troops in Grimaylov town and his property was looted. However, his wife and children escaped from Denikin troops and now they don’t have means to… Chairman of the village council…Signature’. Behind those few words there is a huge personal tragedy of my mother. She hardly ever talked about it. I know that after this happened my mother lived with grandmother and grandfather for almost ten years. She had a physical and moral trauma and it took her a long time to recover. She didn’t work. She did housework, raised her son and looked after her younger sisters. My mother hardly ever went out or socialized with others. Her only joy was her sonny Aron. However life went on. Matchmakers began to look for a match for my mother: he was not too young, but mature, and he might be as well a widower. So my parents met.

My father Mothel Rozhavskiy was 7 years older than my mother. He came from Gorodnya town in Chernigov province. My paternal grandfather Moishe, born in the 1850s died before I was born in the early 1920s. I don’t know what he was doing for a living, either. I have dim memories about my grandmother: a short meager old lady wearing a kerchief. I don’t remember her name, though. My grandmother died in the late 1930s at the age of almost 90. There were 14 children in the family. I knew my father’s sisters Dvoira Kirpichnikova, Lisa Karasik and Etah. I saw them several times when we visited grandmother in Gorodnya in the 1930s. They had big families, but I don’t remember any of their children.

My father had a traditional Jewish education: cheder and Jewish primary school. My father was recruited to the czarist army during WWI 8 and was in captivity. He got married after he returned to Russia. I don’t know his first wife’s name. In 1920 his son Irma and in 1922 his daughter Minna were born. After the daughter was born my father’s wife fell ill. I don’t know exactly what disease caused her death. In 1924 my father became a widower. He was raising his children daring not to bring them a stepmother. Only my mother with her love and kindness to children raised my father’s trust. In 1929 my parents got married. They didn’t have a wedding since none of them was religious. My father knew about my mother’s tragedy, of course, and was tactful and sympathetic with her. My parents registered their marriage in the registry office and had a small wedding dinner at home inviting only relatives to it. For some time after the wedding my parents lived in Bragin town in the neighboring Gomel region in Belarus. My father worked as a storekeeper at a mill. However, my mother was missing Chernigov where her parents and sisters lived and in early 1930, shortly before I was born, my parents moved to Chernigov.

Here on 19 March 1930 I came into this world. I remember our apartment in a one-storied building in the very center of Chernigov. It was a nice apartment: one big room and a smaller room. There was my parents’ big bed in the big room, an oval table and a big cared cupboard. We, children, slept in a smaller room. There were iron beds with feather mattresses and heaps of pillows. There was electric lighting, but there was no gas. There were heating stoves in each room and one in the kitchen. My mother cooked on a primus stove 9 – they were ‘hissing’ in every kitchen then. Our neighbors were Russian: they were the Uspenskiy family. They were our parents’ friends and Maria Sergeyevna often invited me to a meal. Like all children, I didn’t quite like to eat at home and my mother took my breakfast to our neighbors and I enjoyed having breakfast there.

We had neighbors of various nationalities: Jewish, Ukrainian, Russian and Byelorussian. We were on very friendly terms. One of my first childhood memories is associated with summertime when housewives made jam. Primus stoves were too small for making jam. There was a huge pan placed on bricks and fire made underneath. Housewives took turns to make jam. They were stirring their jam and all children lined up with their saucers and spoons to try the foam generated by boiling jam.

Of course, I cannot remember famine in 1932-33 10. However, I know that only thanks to my father working at the mill our family and my grandmother and grandfather survived. My father received monthly rationed food that we shared with grandmother, grandfather and my mother’s sisters. My stepbrothers and sister became friends and my father loved my mother she seemed to have forgotten her sorrow and thawed out. In summer 1934 another disaster struck our family. Aron and Irma went to bathe in the Desna River, got in a whirlpool and sank. There were many people on the beach and rescuers arrived right away. They took both of them onto the bank, but …they only managed to resuscitate Irma, but Aron, my mother’s joy and her favorite, died. My mother withdrew into herself for several years again. She even had to send me to the kindergarten because she couldn’t keep the house and look after me. I remember when I went to the kindergarten alone walking over a bridge over a small river. Once I was late: there was a film shooting in Chernigov and I stayed there gazing at horse riders wearing felt cloaks with their swords galloping over the bridge. I forgot where I was going and what I was to do. Then when they finally discovered me my mother came in tears. Since then I never attended a kindergarten and my mother always kept an eye on me. She never let me come close to the water and I never learned to swim.

Perhaps, my mother loved me more than other children, but she also treated my stepbrother Irma and stepsister Minna like her own children. We were hard up and even though we were living in the center of the town, my mother bought a cow. The cow was in a shed in our yard and all our neighbors’ children took turns to take it to the pasture. My mother sold milk and was saving money dreaming of sending Irma and Minna and then me to college. Once two calves were born and a correspondent of a Chernigov newspaper came to our yard to interview my mother. He also took a photograph of her as if the birth of these two calves was her own accomplishment. Nevertheless, I was very proud of my mother showing people this newspaper with a picture of her.

My father wasn’t a member of the Communist Party, but like all Soviet people felt delighted reading about achievements of the Soviet regime: about the first 5-year periods 11, construction of socialism and communism and was a real patriot. We celebrated 1 May and 7 November 12 at home. I looked forward to parades. I was dressed up, had ribbons in my little plaits and my father took me to the central square. There was often a common table set under the lime trees in the yard. There was a record player on a stool and adults and children danced to the music and sang songs: old romances and Ukrainian songs and new Soviet songs. Generally speaking, we had an absolutely Soviet family. Our parents spoke Russian in our presence and only occasionally they exchanged a few Jewish phrases when they wanted to keep the subject of discussion a secret from us. However, I understood many words in Yiddish since my grandmother spoke Yiddish to my mother and her sisters and the sisters also talked in Yiddish.

We didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays at home, but at Rosh Hashanah, Pesach and Chanukkah we were due to visit grandfather and grandmother and the whole family got together. I had no idea what kind of holidays these were or why they were celebrated. All I remember is that children were given money at Chanukkah and there were sweet doughnuts and potato pancakes and sweet pancakes. The most plentiful was celebration of Pesach. There was gefilte fish, chicken, jellied meat and sweet tsimes. My grandfather conducted seder and one of the boys posed questions. I didn’t find it interesting. Sometimes we visited grandmother on Friday before Sabbath. We sat down at the table that was set for dinner. My grandmother lit candles and started reciting a prayer and I couldn’t wait until it was time to have something delicious. My grandmother saved something that each of her grandchildren liked for Friday: for some it was a cookie or candy and for me she put a slice of herring or something pickled onto my plate.

In 1938 Irma finished school with a ‘golden medal,’ i.e. with all excellent grades. My mother kept her word. She had been saving money for her children’s education for a long time. Irma moved to Leningrad where he entered the Industrial College. Later, in 1940 Minna entered this same college.

In 1938, when Irma finished school I entered the first grade of the school where he studied. This Russian school was quite at a distance from home, but this was the best school in Chernigov. My classmates were of various nationalities, but our teachers treated us nicely. I studied well. In 1940 grandfather Borukh died. I wasn’t taken to his funeral, but my aunts told me that it was a Jewish funeral.

In June 1941 I finished the third grade and my mother was going to send me to my father’s sisters in Gorodnya for the summer. We were supposed to depart in the end of June, but on 22 June Molotov 13 spoke on the radio and we got to know that the Great Patriotic War began. None of my family seemed to know or even assume that there was a possibility of the war. It was quiet in Chernigov at first. There was no panic. The war seemed to be far away, but all men including my mother’s sisters were recruited to the army on the first days of the war. My father was beyond his recruitment age and he stayed with us. Besides, my father was very ill. He had stomach aches and suffered from aftereffects of his past tuberculosis. My father didn’t want to leave home. He believed that we didn’t have to panic, that Germans were a civilized nation and were not going to harm Jews. He judged Germans from the time of his captivity during WWI. However, my mother didn’t want to stay in any circumstances. Some sixth sense, her instinct of self-preservation was forcing her to evacuation and she actually raised the rest of the family. It was hard to leave: people were storming into trains and our numerous family with the children and my old grandmother it was more than we could manage. My father made some arrangements with villagers and in the middle of August they brought a wagon to our house. We loaded our simple luggage and headed to Novgorod-Severskiy. My grandmother, Sima with her two children and Bodana and Fania were in the wagon with us. Sarrah and Alik, Zelda and Lisa with their children were on another wagon. So this bunch of us reached Novgorod-Severskiy, an old town located in the very north of Chernigov region. It was like quite an adventure for us, children, and we didn’t understand why our mothers were crying. It was so interesting to be traveling to other places on a wagon. In Novgorod-Severskiy we boarded a boat with thousands of other refugees. It brought us to a railway station. The boat was stuffed with refugees. Old people were lying on some dunnage. Children were crying and my brothers and sisters and I began to realize that the war wasn’t just the most interesting adventure. At the railway station we boarded a freight train and departed. We changed trains several times and at the station Navlya of Kursk region (today Russia) we were kept for a few days. We could hear distant explosions: Kursk was bombed. When the train arrived at the platform the boarding only lasted about twenty minutes: people were throwing children and luggage through windows inside. There was crying and screaming. On the adjusting track a train with warriors heading to the front stopped. I shall never forget this picture: children screaming, mothers and old women crying and serious faces of young guys with guns going to fight the fascists.

We managed to board one railcar. We were heading to the Urals. The train moved slowly letting military and sanitary trains pass. At bigger stations we jumped off with pots where they gave us soup or cooked cereals or just boiling water. We managed to exchange some food at stations. On the road my father either fell ill or ate something tainted, or it was acute condition of his chronic disease. At Mukhnatin station of Tambov region, 2000 km from home my father, mother and I got off the train. My father was sent to a hospital immediately and my mother rented a room from a Russian old man. My mother went to the hospital every day and cried at nights. On 28 October 1941 my father died. My mother, our landlord and I buried him in the local cemetery. My mother seemed to have no tears left so much distress she went through in her life. As for me, it was the first death of my dear one. After my father’s funeral I had a high fever and probably this helped my mother to hold on: she had to bring me to recovery. The old man tried to convince us to stay in Mukhnatin, but as soon as I recovered we left for Orsk where our family was.

We arrived at Orsk, a small town in Chkalovsk (present Orenburg) region. There was a fortress in the town where a harrison deployed. Local population resided in private houses for the most part. Our family lived on the outskirts near a power plant and bakery factory. This was a district of employees of these enterprises.

All of our relatives rented a small room in a private house. We slept on the floor side by side. My mother and I were the last to arrive and the only sport left for us was near the door. We slept with our clothes on and wrapped in everything we could find: blankets, coats or fur coats. But we still woke up in the morning covered with hoar frost. It was end of November and when we came it was severe winter in the Urals already. My mother, her sisters and aunt Lisa went to work at the bakery. They worked in the dried bread shop drying bread for the front. My mother always over fulfilled the standard quantity 20-25%. Everybody worked for the front, for the Victory! For her outstanding performance my mother received a package of dried bread that did help us to survive. It didn’t matter that there was pain in my mother’s fingers and they were bleeding, she continued to work hard. This was my mother’s first job and in evacuation in 1942 she became a trade union member. This is the only document we have confirming that we were in evacuation.

I went to the 4th form of a local school. Although I was almost 3 months late I caught up with other children soon and received all excellent marks. There were far too many children in classes due to many children in evacuation, including Jewish children. We had no problems associated with our nationality and in general, we never gave this subject a thought. We were all victims: some children had already received death certificates, some had their fathers missing and others were still in action. I was also an orphan. Teachers had particularly warm attitude toward us, orphaned children of the war. It was a hungry life, particularly for those who were used to high calorie meat food. As for me, what we received at school was quite sufficient. We were provided thin soup with green leaves of sorrel and nettle and probably there was a piece of potato in it. A little spoon of plant oil was added into each bowl. I enjoyed having my soup and at home I had my mother’s dried bread. My mother also received bread in stores per bread coupons. I didn’t have to stand in lines. So we basically were trying to survive. After classes my friends and I went to the hospital. This was a holy mission for us to support the wounded. We helped nurses, took out patients’ bed pans, changed bed sheets and gave food to the patients. But the most important thing was that seeing us brought a warm spark into their eyes and they smiled. I read them poems by Pushkin 14, Lermontov 15. Occasionally we made them a concert in the biggest ward. So I think I made my contribution into the common cause of victory.

My brother Irma volunteered to the front on the first days of the Great Patriotic War. His division lasted only few weeks suffering great casualties. Irma was one of the unfortunate: he was severely wounded and it resulted in gangrene. Irma went to hospital where doctors rescued his life and his leg. The only thing was that he became lame. In 1942 Irma was released from the hospital. He found us and joined us in Orsk. It was a happy reunion since we survived and sad at the same time when Irma heard about his father’s death. Seeing our routines and our living on the floor Irma went to the town executive committee and being a veteran of the war the managed to arrange for another accommodation for us. My mother and I got a lodging in a small room adjusting to another room three-bedroom apartment in 20, Komsomolskaya Street. There was an old woman living in this next room and an evacuated family from Stalingrad (present Volgograd, today Russia). Then Irma went to study. His college evacuated to Tashkent (today Uzbekistan) and Irma went there, too.

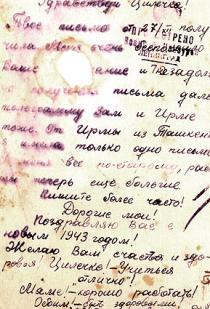

Minna, my stepsister, stayed in Leningrad. She became a flak gunner and stayed in Leningrad during the siege 16. Occasionally we received letters and cards from Minna, cheerful and optimistic. She never wrote about the horrible days of siege. Minna even managed to sent us money: 100 rubles. We received the last card from Minna on the New Year eve of 1943. My sister sent us greetings and wishes of victory. This was the last time we heard from Minna. Later an acquaintance of hers wrote us that on 8 August 1943 Minna got into the fiercest battle for Leningrad. A group of flak gunner girls came out of a theater at noon. Minna was one of them. Many perished. Minna lost her arm, her leg and was severely wounded in her stomach. She died a few hours after. I took this letter out of our postbox and didn’t tell my mother about my sister’s death for a long while. I went to my neighbors from Stalingrad and had my cry out. A few months later those neighbors received a death certificate for their son and my mother went to support them in their grief. Then they told her about Minna. My mother grieved after her. She loved Minna like her own daughter.

We were in evacuation until Chernigov was liberated in late 1943. My mother applied for obtaining permits for reevacuation, but we left home before we had any documents issued to us. Somehow we managed to make arrangements at the railway station to get on a train. My mother couldn’t even take her employment records book from her work since we were going almost illegally. I only had my school record book. Our trip lasted for a long time. We had to change trains in Moscow and we stayed there at the railway station for a few days.

Chernigov, my hometown, was in ruins. Fortunately, cathedrals and major historical monuments, were not destroyed. A bomb hit our house, however, and there were only iron bed frames sticking from ashes. Our former neighbors Uspenskiys gave us shelter. They were living in a nearby house. They only lived in one room, but they gave us a warm welcome. They also told us that Jews who stayed in Chernigov were killed. Doctor Radomyslskiy’s family, our prewar neighbors, and a few other Jewish families perished. Our crazy old neighbor, a single man, whom we laughed at when we were kids, went to a mental hospital before the war and was exterminated along with other patients during the war.

My mother’s sisters and grandmother stayed with some acquaintances. About two months later aunt Sima, who went to work at the woolen yarn factory received a room in a three-bedroom communal apartment 17, and our whole big family went to live with her. So we lived removing mattresses and pillows from the floor in the morning making the room look different. At night we slept on the floor like we did in evacuation. Even a dinner table served as a bed for one of us. Then Sarrah and Alik moved out and aunt Zelda and her children followed them and there was more room.

My mother and I continued living with aunt Sima. I went to school and had all excellent marks, as usual. I became a pioneer in evacuation and now I joined Komsomol and took an active part in public activities. At one time I was chief of the Komsomol unit of our school. My mother went to work as a nurse in hospital. Since I was used to helping around in hospitals I went to my mother’s work almost every day after classes. I washed floors and helped patients. I felt so very sorry for my mother and wanted to help her. Irma supported us. After finishing college he worked in Chernovtsy. He married Anna Nikolayeva, a Russian girl from Leningrad and moved to Leningrad. Their son Mark was born in 1952. In 1970 Irma and his family moved to Israel. He worked there many years longer and now he receives pension as an invalid of the Great Patriotic War. His son Mark lives in the USA.

In 1949 I finished 10 grades with a good certificate. I could go to any higher educational institution like Kiev University, for example, considering its high prestige, but I had to start work to earn money as soon as possible and this made me go to Chernigov 2-year Pedagogical College. Actually, I was fond of literature and wanted to become a teacher since childhood. I studied well. Firstly, I liked it, and secondly, I was stimulated to receive a stipend for advanced students [Editor’s note: students who had all excellent grades in the institutions of higher education were entitled to receive the so-called “Lenin’s stipend,” which was somewhat more than the regular one]. It was very important for our poor family. Besides, when I entered this college, my mother and I rented an apartment near the college so that Sima and her children felt more comfortable in their room. I studied during the period of state anti-Semitism, so called struggle against rootless cosmopolites 18. I didn’t face it, but many Jewish lecturers were fired from the college. I remember our lecturer on Marxism-Leninism asking for our notes to prove that he didn’t say anything seditious to his students. It didn’t help him: he was fired.

In 1951 there was a job assignment 19 distribution. I was prepared to go anywhere since my mother was going to follow me anyway. I had a Russian friend at that time. Her name was Valia Chukhray. Her parents liked me a lot. They always tried to make me eat with them and made gifts. Valia’s father had a high position in the town military prosecutor’s office. Shortly before the distribution of job assignments he fell ill with brain cancer. He was rather upset of not being able to help me with my job assignment. He told me to not agree to go to Western Ukraine that was recently annexed to the USSR 20 due to banderovtsy movement 21. He was very happy to hear that my job assignment was in Kherson region in the south of Ukraine.

I chose Zagoryanovka village near Kherson hoping to be able to often go to Kherson. When I came to the regional department of education its chairman looked at me (and I was a thin short girl) and said: ‘I don’t think it’s worth for you, girl, to go to Zagoryanovka. It’s not the place a young girl would like to be at. I will send you to Tehinka. There is big construction there. They need teachers with diplomas and this place is better than Zagoryanovka’. So I went to Tehinka. They welcomed me warmly and showed me the school. I rented a room from nice Ukrainian people: Marusia and Kolia who liked me, too. The department of education paid my rental fees and gave me money for wood and kerosene. So I was a desirable tenant. Three weeks later my mother joined me. She lived with me ever since.

There was a kolkhoz 22 named after Kalinin 23 in Tehinka. It was a poor kolkhoz. Its members were paid with food coupons for work. Since I had a regular salary I also became a desirable fiancée. Young people proposed marriage to me, but my mother and I declined them joking about it. Teaching was easy for me. I taught in the 5th, 7th and 8th grades. The 8th grade was the first year of higher secondary school. They were the children who wanted to have a complete secondary education. They listened to me with attention and I was eager to inspire love to the Russian literature in them. As for the 5th grade those children didn’t bother to listen to me. Why did they need Russian? They were noisy and caused problems. Once I lost my temper and pushed one of those hooligans. I forced him out of his desk and pushed him out of the classroom. They began to respect me then: ‘Hey, she can fight!’ and were quiet at my lessons. After working for a year I got a transfer to Daryevka, a neighboring village, since a new doctor came to Tehinka and his wife who was a teacher, needed this vacancy. I didn’t mind since Daryevka was even bigger than Tehinka and there were more comforts there. I spent a few more weeks in Tehinka and met a Jewish girl. Her name was Fira Spivak. She had her job assignment in this village. I supported her since I was well aware how hard it was for a girl from a town to live in the village. Her brother Naum Spivak came from Kherson to visit his sister and so I met my future husband. Naum began to visit me in Daryevka. He courted me very nicely.

Naum Spivak was born in Kherson on 22 April 1925. His father Tsala Spivak was a really religious man. Although Naum was a Komsomol member, he used to go to the synagogue with his father before the war and knew Jewish customs, traditions and holidays well. However, Naum wasn’t religious and didn’t observe traditions, but he knew them. When the Great Patriotic War began, Tsala joined Territorial Army 24, and Naum, his mother and sister Fira were in evacuation in Saratov region (today Russia). His father perished in occupation. After Kherson was liberated Naum returned to his hometown. Before evacuation Naum finished 8 grades at school and when back in Kherson he passed his exams for a higher secondary school extramurally. At the age of 16 he entered the Agronomist Faculty of the Agricultural College. After finishing it he went to work as chief agronomist in a kolkhoz and in 1952 he already was an agronomist of the agricultural department in Kherson. I fell in love with him and we got married on 3 October 1952. Almost the whole village was invited to our wedding. It was a joyful wedding party. Many young people attended it. Almost immediately after the wedding he was sent to support agriculture improvement following the decision of Khrushchev 25 to send specialists to villages. We went to Sadovo, a big village where I went to work at school. A year later on 19 September 1953 my daughter Inna was born. I named her Minna after my sister when she was born, but when my daughter was to obtain her passport she changed her name. This was a hard period of time: everybody was talking about the Kremlin ‘doctors’ plot’ 26. We were so worried about it and never believed one bit of the official propaganda. I need to mention that neither my husband nor I faced any of anti-Semitic demonstrations. Perhaps, this was because we were working in a village where people were nicer and more sincere.

Stalin’s death in 1953 was a shock for us. We were whining: how were we to live without him? My husband and many others submitted their applications to the Party. A year later my husband joined the Party. We lived in Sadovo four years. Here in 1956 my second daughter named Ella after Naum’s grandmother Elka was born. Shortly after she was born my husband was transferred to Nikolaev region and I went to work as a teacher there too. We always followed my husband. In 1958 my husband was transferred to Kherson. In the first years we rented an apartment and later we invested in construction of a cooperative apartment. This is where I live now.

I was very happy with my husband. He was an amazing person: kind, cheerful, very smart and an erudite. It seemed there was no existing subject of discussion that he couldn’t talk about and no questions he didn’t know answers to. My husband always had good positions and earned well. We had an interesting life going to the cinema, to theaters and spending vacations at resorts. I had everything I ever wanted. I was always in public as a teacher and later deputy director at school. I joined the Party and was secretary of the Party unit. I wouldn’t have made a career otherwise. I always dressed in trend and beautifully. Naum enjoyed buying me new things. My mother helped me about the house and I wasn’t overloaded with work at home. In 1981 my mother died and we buried her in the town cemetery. Naum’s mother had died a long time before, his sister Fira moved to Israel with the first wave of emigration in the 1970s. My husband’s sister died in the early 1990s. She didn’t have children. My family have always been sympathetic with Israel, but we never considered emigration.

In the last years before perestroika 27 Naum worked at the machine building plant as an engineer, although he didn’t have an engineering education. When perestroika began he established a cooperative manufacturing construction materials. His cooperative was one of 15 other cooperatives at the plant that survived and developed into a successful company. I can say that perestroika gave my husband a full opportunity to reveal his talents and skills. Our life improved even more. We bought nice furniture and a dacha and supported our children even more.

Our girls studied well at school and got a higher education. Inna finished the Faculty of Mathematic of Kherson University, and Ella finished the Faculty of Physics at this University. Both of them have Jewish husbands. Inna’s husband Leonid Rozenfeld is also a mathematician. Ella’s husband Valeriy Lifshitz is an engineer. Inna is deputy scientific director in the experimental lyceum school in Kherson. Her son Roman, born in 1980, finished Polytechnic College and works at the same plant where my husband used to work. Ella, her husband and daughter Yelena moved to Israel in 1990. She didn’t want to move there leaving us here, but her husband insisted on their departure. Yelena, born in 1977, got married very young in Israel. In 1996 my Ella called me and said: ‘Mother, congratulations on your having great granddaughter Daniel-Nehama!’ When I heard that my granddaughter was named after my mother I burst into tears of happiness. Naum went to Kiev to obtain a visa for me and sent me to Israel for a month. So I visited my daughter and saw my great granddaughter. I admire Israel, it’s just amazing! It’s a civilization in a desert created by its people. However, I wouldn’t stay to live there: the climate is hard and besides, I love Ukraine. It is my home. It’s familiar and dear to me.

In the recent years my husband and I didn’t work. We’ve become Hesed clients. Then they offered me to host the ‘warm home’ cooking meals for older Jews and having them come to my home to eat. Surprisingly for myself I agreed to do it and since then my husband and I gave a lot of our strengths to Hesed. They provided food products to me, but I also bought some to make my cooking delicious and variable. I participated in a few seminars for Hesed volunteers. Only at my old age I learned about many Jewish traditions and holidays. Now I know what needs to be cooked for each holiday and I make it for my family. Of course, I haven’t become religious, but this all is very interesting to me. A Jewish newspaper issued in the south of Ukraine wrote about our ‘warm home’ calling it the best one. Regretfully, my Naum died half a year ago. I am in the mourning and I miss him so much, but I always remember that Naum liked me to look nice and be among people and I try to pull myself together. I often attend Hesed to listen to interesting lectures and concerts. My children and friends do not let me feel lonely.

1 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.2 Pogroms in Ukraine

In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.3 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.4 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during WWI, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.5 Odessa

The Jewish community of Odessa was the second biggest Jewish community in Russia. According to the census of 1897 there were 138,935 Jews in Odessa, which was 34,41% of the local population. There were 7 big synagogues and 49 prayer houses in Odessa. There were heders in 19 prayer houses.6 Komsomol

Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.7 Denikin, Anton Ivanovich (1872-1947)

White Army general. During the Civil War he fought against the Red Army in the South of Ukraine.8 World War I World War I, military conflict, from August 1914 to November 1918, that involved many of the countries of Europe as well the United States and other nations throughout the world

World War I was one of the most violent and destructive wars in European history. Of the 65 million men who were mobilized, more than 10 million were killed and more than 20 million wounded. The term World War I did not come into general use until a second worldwide conflict broke out in 1939 (World War II). Before that year, the war was known as the Great War or the World War.9 Primus stove – a small portable stove with a container for about 1 liter of kerosene that was pumped into burners

10 Famine in Ukraine

In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.11 Five-year plan (5-year plans of social and industrial development in the USSR), an element of directive centralized planning, introduced into economy in 1928

12 5-year periods between 1929-90.12 October Revolution Day

October 25 (according to the old calendar), 1917 went down in history as victory day for the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. This day is the most significant date in the history of the USSR. Today the anniversary is celebrated as ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’ on November 7.13 Molotov, V

P. (1890-1986): Statesman and member of the Communist Party leadership. From 1939, Minister of Foreign Affairs. On June 22, 1941 he announced the German attack on the USSR on the radio. He and Eden also worked out the percentages agreement after the war, about Soviet and western spheres of influence in the new Europe.14 Pushkin, Alexandr (1799-1837): Russian poet and prose writer, among the foremost figures in Russian literature. Pushkin established the modern poetic language of Russia, using Russian history for the basis of many of his works. His masterpiece is Eugene Onegin, a novel in verse about mutually rejected love. The work also contains witty and perceptive descriptions of Russian society of the period. Pushkin died in a duel.