Teodor Kovac

Novi Sad

Serbia

Interviewer: Ivana Zatezalo

Date of interview: March 2003

As previously arranged, I arrived at Mr. Kovac’s place for our interview. He opened the door for me, helped me take off my coat and took me into the room. He was really good-mannered, a real gentleman. He and his wife, Ana, welcomed me in a really friendly way. First they offered me juice and wonderful home-made cookies. Only after that, said Mr. Kovac, we would start the interview. There was a beautiful wooden table with six chairs in the room. We sat opposite each other and relived the story of his past.

My family background

Growing up

During the war

After the war

Glossary

I’ve found documents that say my ancestors lived here in Backa [part of Voivodina] 1 ever since the beginning of the 19th century. They are all from here or from Slavonia. [Today it is split between Croatia and Serbia. Slavonia is the area between the Drava, Danube and the Sava rivers.] I don’t remember my great-grandfathers and my paternal great-grandmother. I only remember my great-grandmother on my mother’s side. She was born around 1840 and was about 92 years old when she died in 1932. She was born somewhere here in Backa. I don’t know exactly where. I don’t know about their financial situation, nor their living standards. They were probably poor like everyone else at that time. They must have been religious as other people back then. I don’t mean Orthodox, but they probably observed all the holidays that were celebrated anyway.

I know that my great-grandfather, my grandfather’s father, was married twice. He had several children from his first marriage, then his wife died. He remarried and had many children with his second wife, too. She also had several children before, so probably all together there were 15 or 16 children. With the exception of my grandfather, and apart from those who died, they all went to America. During World War II the contact to these relatives stopped, so I’m not in touch with their descendants.

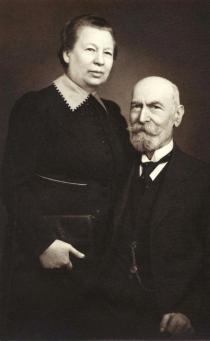

My grandparents on my father’s side died ten or even more than ten years before I was born. My paternal grandfather was called Adolf Kovac and he was born in Ruski Krstur [Bacskeresztur before 1920]. He was born as Kohn; later he changed his family name. In 1896, during the celebration of the thousand-year anniversary of the arrival of the Hungarians to Pannonia, the Jews collectively changed their names to Hungarian last names. [Editor’s note: There was never a collective magyarization of family names in Hungary. It is true, however, that voluntary magyarizations accelerated towards the end of the 19th century, and the 1896 Millennium Exhibition in Budapest gave a special impetus to such efforts.] Magyarization of family names was a sign of belonging to a certain milieu. Gratitude was expressed this way to the Hungarian nation which acknowledged the equality of Jews. It was the first time in two thousand years of Jewish history in the land of Hungary that full equality was given to Jews. [Civic rights were granted to Austro-Hungarian Jews in 1867, the year of the so-called Compromise of 1867.] The Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy was ethnically so mixed, that Hungarians hardly comprised 50% of the population. The rest were Serbs, Croats, Slovaks, Romanians, Ruthenians and Ukrainians. The Hungarians willingly accepted this kind of declaration of loyalty of Jews. In 1896 my grandfather changed his last name to Kovacs. [Kovac is the Serbo-Croatian spelling of the Hungarian Kovacs.]

I don’t know what education my grandfather had. I think he must have attended cheder and Jewish elementary school, as all other Jews at the time. He was engaged in everything. I know that for some time he was a manager of a quarry in the village of Paragovo and probably lived either in Paragovo or in Kamenica. I remember that I found a prescription before the war, which was written and prescribed to my grandfather by Jovan Zmaj. [Zmaj, Jovan Jovanovic (1833-1904): well-known Serbian poet, physician and academician.] I don’t remember from what year it was. My grandfather had a cold and Jovan Zmaj prescribed him some cough-syrup. Because of that prescription I know that he lived either in Kamenica or in Paragovo. My grandfather was moderately religious, he wasn’t Orthodox though, he was far from that. I don’t know what his mother tongue was. It wasn’t Yiddish though, probably Hungarian, but I don’t know for sure. He also spoke German. My father told me that my grandfather served in the army for a long time. I don’t know for how long and I don’t know where. He died just a few days after World War I broke out, that is, sometime in August 1914. I don’t know anything about his brothers and sisters.

My father was called Arpad Kovac, and he was born in Pivnice [Pinced at the time] on 27th February 1893. It is a village in Backa. He graduated in Novi Sad. His parents moved to Novi Sad while my father was still small. My grandfather was doing business at the quarry in Paragovo at that time. My father spoke all three languages very well: Hungarian, Serbian and German. He also knew French very well. My father wasn’t religious, not at all. He went to school in Novi Sad, and he also studied in Pest [Budapest]. After finishing law school, he worked as a lawyer in Titel for a year and a half. Then World War I broke out and he joined the army. After the war he returned and opened an office in Novi Knezevac, where I was born. He was killed in 1941 around 12th or 13th October. He was deported along with the Jewso of Banat 2 to Belgrade and probably he was killed in Jabuka [infamous Serbian concentration camp].

My father had two brothers and two sisters. One of his brothers was called Boldog Kovac. He was a lawyer in Novi Sad, on Mileticeva Street. He was about seven or eight years older than my father, and he was born somewhere in Banat, I think in Kucura. He lived at the corner of today’s Jevrejska Street and Bulevar where the Sveca boutique is located. He died of a stroke in 1939. His daughter was married and lived in Belgrade.

Boldog’s wife and daughter perished along with the Jews from Belgrade and Banat in Sajmiste 3. His son studied food industry technology in Germany. He received his doctorate in 1933 when the Nazis came to power, and then left for Palestine where he survived the war. He died 10-15 years ago. His wife died, too. He has a son, who works as a physicist at the University of Tel Aviv. He’s probably already retired. He has a son and two daughters, but I don’t know their names.

My father’s oldest sister, Piroska, was a lawyer. Her husband’s family was quite wealthy and among the richest citizens of Novi Sad, not only among the Jews but among all the citizens; they had everything. They owned a farm in Sremski Karlovci, even today they call it after his name, though 60 years have gone by.

Piroska’s husband, was called Rot. His parents had a fabric store, so they called him ‘Stoff-Rot’ [Fabrics-Rot]. He managed to go with his wife and a three-year-old child to England from Novi Sad. They first went to Switzerland, from Switzerland to Portugal, and then from Portugal to England. Piroska went to London to give birth to the child there in order to get English [British] citizenship. Back then England was something America is today. She gave birth on the day World War II broke out. Afterwards they came back here. They survived the war, but Piroska’s husband died shortly afterwards in 1946 or 1947; he was buried in Novi Sad.

They had three daughters and a son. One of them committed suicide shortly before deportation, I don’t know how she did it. The other daughter managed to leave for England from Hungary with her husband and her small child during the war. Leaving for England wasn’t an easy thing to do back then. From England they traveled further on to Chile. The third and oldest daughter was a doctor. She managed to survive in Budapest by declaring herself Hungarian. She was very talented when it came to languages and thus spoke several languages without an accent. From her looks it was easy to conclude she was Jewish but she managed to survive. After the war they all met.

The three sisters had a brother, George. He had been in labor units and survived and came back to Novi Sad. He was somewhere near Szeged [Hungary]. Since Szeged was liberated before Novi Sad he arrived in Novi Sad just before the Hungarians left Novi Sad. [The interviewee is referring to the Hungarian occupation of Yugoslavia] 4. He fled from Yugoslavia, and his sister, the doctor, left legally from Yugoslavia and they all met in Chile. Georg became a journalist and today, I hear, he is the publisher of a Spanish journal or weekly newspaper in America. He grew up in Chile, so Spanish is his third mother tongue. Georg also made the last interview with Che Guevara. He managed to get to Che Guevara when he was besieged and made him give an interview. [In 1967, directing an ineffective guerrilla movement in Bolivia, Che Guevara was captured, and later executed by government troops.] Here newspapers presented the success of ‘our man’ from Novi Sad. Once he called, that’s how I knew he was alive. Now I don’t have any contact with him any more.

My father’s other sister, Aunt Ernestina, was a big Zionist, just like my father’s younger brother Balint. Once my aunt and uncle traveled to Palestine to visit my uncle’s son who lived there. In those times it was a big adventure. They traveled by ship because it was impossible to travel any other way. They spoke some French, the other passengers on the ship also knew French, so they understood that my uncle worked for the government. He was the Minister of Justice of Yugoslavia.

Aunt Ernestina married a court clerk, named Ede Almai. He had an exceptionally nice handwriting. When the Jewish Cultural Home [teachers’ school today] was being built on Petra Drapsina Street, he wrote a charter. His calligraphy was put into a coated box, which was built into the foundations, and it’s still there today.

Ernestina’s family lived in Pavla Pap Street. Ernestina and her husband were both deported and killed in Auschwitz. Today their former house is half destroyed. They had a daughter, and I’ve heard that she died of tuberculosis during World War II. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Novi Sad. Up until a few years ago her photo was engraved on her tombstone. I don’t know how, but it suddenly disappeared.

My other uncle, Balint, lived on Mileticeva Street. He died shortly before World War II. He had a heart attack. I don’t have any other information about him.

My maternal grandfather, Adolf Berger, was born in Vrbas [Verbasz before 1920], here in Backa. They didn’t magyarize their family name. He was a rather introverted person. At that time Adolf was considered a Scandinavian name. Hitler hadn’t yet been heard of. My grandfather was religious; every Friday and Saturday he would go to the synagogue. He didn’t wear a beard, a kippah or a hat, though. They regularly followed the news and listened to the radio. He read in Hungarian and German, too. They had a subscription to Politika [a daily newspaper, which still exists in Serbia and Montenegro]. My grandfather wasn’t a member of any organization.

My grandfather had seven sisters, but not a single brother. These sisters, except for one, all lived in Subotica [the second city of Voivodina], but shortly before the war they gradually all moved to Novi Sad. They all perished. I don’t know their names and dates of birth.

My grandparents’ apartment was situated in today’s Avgusta Cesarca Street. They had two rooms facing the backyard. It looked like a family house located in the middle of the city. There was water and electricity, and they heated the house with coal and wood. There was a garden, too, with flowers and vegetables, but they kept no animals. They were mainly in contact with their neighbors and with Jews. To my knowledge, they had no other friends. They used to go on vacation because my grandfather worked at the railroad and had the opportunity to travel for free. I don’t know whether they took my mother along with them.

I don’t know much about my grandmother’s and grandfather’s childhood. I know that, while my grandfather was at high school his mother died and his father remarried later. The stepmother wasn’t very motherly. My grandfather finished high school in Baja [today in the south of Hungary] and enrolled in medical school in Vienna. In those days medical science in Vienna was among the best in the world. He had no money to pay for his studies, so he dropped out a year later.

My grandfather had a hard life. Austria-Hungary was economically expanding and gaining strength: railroads were built extensively and there was a constant demand for railroad personnel. He completed a course and started working at the railroad [the Hungarian State Railways]. Soon he became station manager in Dalj [today Croatia, called Dalja before 1920], then in Borovo [now in Eastern Slavonia, Croatia] and after World War I he got transferred to the main office of the railroads in Subotica, from where he retired. After he retired, he came to Novi Sad and they bought a house. My grandfather didn’t serve in the army because he worked at the railroads, and railroad workers were exempt from service.

My maternal grandmother was born in Dalj on the Danube in 1874. Her name was Irma Veltman. The Veltmans came from Curug [in Voivodina, called Csurog before 1920]. A few years ago, a man told me that they still call a house in Curug as ‘Veltman’s house’. One of the Veltmans, Martin Veltman, went to Palestine in 1938. He was a lawyer in Novi Sad. There he became Meir Tuval. For some time Palestine didn’t have enough personnel, so they hired ambassadors under contracts and he, too, was hired as an ambassador. During the war he was called Meir Marcika, the representative for Sochnut 5 in Istanbul with a mission to try to help European Jewry. He has a son, I think he has a daughter, too, but I don’t know for sure. His son is called Sadija; he was a professor of political science at several universities, including Tel Aviv and Washington. His main interest was to create peace among warring parties, to conclude peace treaties. He wrote a study on Somalia and was here, too. So, the grandson of a Curug Jew became an expert on Somalia... They still speak Serbian well.

At home my grandparents mainly spoke German and Hungarian but they were also quite fluent in Serbian. My grandmother didn’t wear a wig, she wasn’t observant to such an extent, but she kept a kosher household. Sabbath was observed, they went to the synagogue every Friday and Saturday, and of course on holidays. Neither my grandmother nor my grandfather was very much into politics, but my grandmother was rather active in a Zionist organization for women.

My mother was their only daughter. She was called Olga Berger. My mother was religious. She regularly lit candles on Fridays. She went to the synagogue on holidays. Also, she didn’t allow us, my brother and me, to eat pork; we had kosher food. When we ate bacon with my father in his office sometimes she pretended she didn’t see us. My father wasn’t religious, although we celebrated Jewish holidays together. My mother was a housewife.

My parents probably met, like others at that time, through a shadkhan – a matchmaker. They got married on 10th December 1912 in Slavonski Brod [in Croatia, called Brod in 1912]. I know that the wedding took place in the synagogue. Besides they also had a civil marriage.

As far as I know, my father held no position in the Jewish community. They were politically non-committed, they didn’t belong to any party. Father served in the army during World War I, and I think he once said that he worked himself up to the rank of lieutenant.

They didn’t socialize that much with the neighbors. My parents mainly socialized with Jews. One neighbor was a farmer and had a coach. He was a sort of country coach. The other neighbor was a tailor. Sometimes they went on vacations. At that time they mostly went to spas, but not that often. My parents were in touch with their relatives, but there weren’t any in the village. Their relatives mainly lived in Novi Sad; outside Novi Sad they only met occasionally.

They dressed just like other middle-class citizens did at the time. We weren’t rich, but we weren’t poor either. I remember that my father bought a house in 1928; and then he added an annex to it. For village conditions it was quite a big house with a big plot of land facing the street. I remember when water supply was introduced and when they built the bathroom. That was at the time I was attending school already. There are artesian wells in Novi Knezevac [Banat], and one well was near our house; it was so rich with water that around 15-20 houses got connected to that well and supplied with water. Only during the summer, when the gardens were watered in the afternoon, the pressure declined, otherwise we had plenty of water. We had a garden, where we grew what we liked to grow. We had pets, a dog and a cat, which was pretty common. I also had a squirrel and a hedgehog. We had servants, among them a maid. We had books in the house, but no religious books, and the library was a mess. I remember that one summer I put everything in order and catalogued the books: there were around a hundred books, mainly fiction. Newspapers arrived regularly. There was no public library in the village.

I have one brother, Karlo, who is nine years older than I. He was born in Titel in 1914, three weeks before World War I broke out. Karlo went to university and became a lawyer. He lives in Novi Sad.

I was born on 24th April 1923, in Novi Knezevac, which is a fairly small place in Banat. It’s a district town though. Back then there were no boulevards in Novi Knezevac, it was paved like the villages in Voivodina [with cobble-stones]. Electricity was supplied periodically. At the beginning there was only electricity from noon to midnight, or to 10 or 11 o’clock in the evening; later there was electricity all day.

There were many Jews in Novi Knezevac, around 70 people in total. Jews were, like everywhere in Voivodina, mainly merchants. My father was a lawyer, there was a Jewish doctor, a banker. There was a small synagogue, which the Germans used as a warehouse during World War II, and it continued to be used as such after the war. There was no rabbi, no mikveh, no talmud torah, no yeshivah. Unless my parents forced me I didn’t go to the synagogue. I had a bar mitzvah though.

I don’t remember what my favorite subject was in school. In the 1st and 2nd grade there was only one teacher; he was a good teacher. He died not too many years ago, probably when he was 98 or 99. The 3rd grade was taught by a female teacher, and the 4th by another one. The teacher from the 4th grade lived long, too, when she died I was still working, but I was about to retire. They were good teachers. I had some classes outside school; my parents made me learn music, but they were quickly convinced that it was useless, since I showed no interest.

I had no problems in school for being a Jew. In our class it was the same as in Novi Sad: there were Serbs, Hungarians, Slovaks, Germans and Jews. Several of us were Jews. As a child, I don’t remember anti-Semitism; that was long before Hitler. I remember, in my birth-place the store was just opposite the house where we lived. The owner was a Serb merchant whose wife was half German, half Romanian from Romanian Banat. She spoke poor Serbian, and she would often get together with my mother and they would speak German with each other.

There were several restaurants in Novi Knezevac, one of them belonged to a Jew called Jelinek. It was a casino, a noble restaurant. The second restaurant belonged to a Hungarian, and there were more, but I’ve already forgotten their names. [Middle class] gentlemen mainly went to the casino.

Before the war I attended the school in my birth-place, there were only four grades in elementary school. The 8-year high school I attended here, in Novi Sad. Novi Knezevac is 130 kilometers away from Novi Sad, so it was impossible to travel daily. I lived in Novi Sad at my maternal grandparents’. When the war broke out in Novi Sad [April 1941] I was a graduate; we graduated during the occupation..

Sometime in 1931-1932 we heard about Hitler. Anti-Jewish laws, the so-called ‘Koroscevi’s law’, were introduced in Yugoslavia in 1940. Koroscevi was the minister of education, he had introduced that law in the first grades of high schools and universities. At the same time a law was introduced according to which Jews weren’t allowed to trade with groceries, so it wasn’t only an educational law, therefore we all called it ‘Koroscevi’s law’. [Editor’s note: In October 1940 the Yugoslav government enacted two anti-Jewish laws. One established a numerous clausus for Jews in secondary schools and universities, and the other excluded Jews from trading in certain food items.]

I remember Hitler’s rise to power very well, especially the beginning of World War II. I even remember the Spanish Civil War, the Japanese invasion of China and the Anschluss 6.

Karlo was already a lawyer in 1937; he started his training period in my father’s office, and from there he was doing his exams. He was just finishing his exams when World War II broke out. As a reserve officer he had no war disposition, so in that chaos one unit would send him to one place, the other unit to another place. He arrived in Ujvidek and from here he went on with a troop that was leaving the city. They put him into the barracks [today’s Vidovdanska elementary school] in the evening. He stayed a few days, then the troops went over the bridge to Fruska Gora, in a long column, and the last men blew up the bridge. When they retreated they would take the poles with them. The second bridge was Kraljevic Tomislav Bridge. The whole night they walked in chaos until they arrived in Ruma. The Germans were there and locked them up in wagons in order to take them into captivity. Since the Germans didn’t have enough men, the wagons remained without guards and when the train stopped for the first time after Ruma, those captives from Backa got off and walked to Ilok. In Ilok they crossed the Danube and arrived in Backa Palanka. That way Karlo made it back to Novi Sad and stayed here.

During the Holocaust I spent a full three years and two months in many camps along with my brother Karlo. Apart from short periods of time we were mainly together. We were arrested together, and released together.

Banat was the first place in Europe where, with the help of the local Germans, Jews were cleared out. They were very proud that Banat was ‘judenrein’, clear of Jews. Hardly more than four month after German troops entered Banat, there were no more Jews. They had all been deported. Men were killed soon after deportation and women were in Sajmiste in Belgrade. If they didn’t die of the cold of winter, they were murdered in gas trucks. The gas was released into trucks, which women were locked in. They suffocated. My parents were also killed quite quickly. No one survived. I don’t know if my mother was taken to Sajmiste, whether she died in winter, either froze to death or died from a disease, or if she had survived only to be suffocated later; I don’t know. [Editor’s note: In the Banat the Nazis placed the Jews in camps during the summer and in September 1941 deported them to Belgrade. All Serbian Jews were then deported to various concentration camps and killed. In August 1942 a German report stated that the ’problem of Jews and gypsies had been solved; Serbia is the only country where this problem no longer exists’.]

Both my parents perished. My mother was deported with the Jews of Banat. Novi Knezevac is in Banat. [Banat came under direct German military administration after the occupation of Yugoslavia, in 1941.] My father was deported with the Jews of Banat to Belgrade. First they took them to Novi Becej and put them in a warehouse, where they stayed for probably around five weeks. Then they took them with barges to Belgrade. They released the women and took the men to Topovske Supe 7 in Belgrade; and from there, after a few weeks, they would take them group by group. Most of them were killed in Jabuka, near Pancevo [southern Banat, on the Danube]. A smaller number, about 50 to 60, was killed in Deliblatska Pescara [near Bela Crkva in southern Banat], but most of them were killed in Jajinci [camp near Belgrade]. It was a prewar military rifle range, and there they killed them one by one.

I don’t know where my father was killed, probably in Jabuka. Jabuka is isolated, there is nothing in close range, under it is a large swamp and above that a dike. There is no place to flee, even if someone had tried to flee he had nowhere to go since they had closed it from the sides, under it was water and above it was a settlement. They had put them there and then executed them. Gypsies buried them.

Women and children under the age of 14 were released to find their way in Belgrade. They weren’t allowed to leave Belgrade and had to cope with the situation in any way they could. Those who had no one to go to were given accommodation by the Jewish community: they were put in two synagogues. My mother lived with Uncle Balint’s daughter. She lived in Belgrade and my mother settled at her place. They were taken away on 10th December and brought to Sajmiste. In February there were one or two transports every day. They suffocated them in gas trucks in Jajinci. They buried them first, later, in 1943, they exhumed and burned them – that’s where my mother perished.

My brother and I survived. My father’s two brothers had died before the war. One uncle’s whole family – his widow, his son, his daughter, brother-in-law and his eight-year-old granddaughter – was killed during the Novi Sad massacre 8. The other uncle’s son left for Palestine in 1933 where he survived the war. His daughter, my cousin, stayed in Belgrade and she perished, I suppose she was with my mother so they perished in Sajmiste. She got married quite late and had no children. Her husband was probably killed in Topovske Supe.

My grandmother’s house in Novi Sad, where I attended gymnasium, remained. I remember when we went back. My grandmother had a female lodger who was in the house when my grandparents bought it, after they came here from Subotica in 1920. The lodger was there when we returned to Novi Sad a day before the Christmas Eve in January 1945. [Editor’s note: Orthodox Christian Christmas is on 6th January.] We knocked on her window, she wouldn’t open the door since she was afraid. There was a black-out in the whole city, it was still war, she was alone at home, and didn’t open the door for us. I had managed to save the key of the gate to my grandmother’s house. My brother and I opened the gate and knocked on the backyard door, saying who we were. The woman opened the door and almost fainted when she saw us. She told us that some Hungarians lived in the house, who had been moved there by the Hungarian authorities. Novi Sad wasn’t bombarded, only a few bombs fell on the city. There were a few Hungarian houses among those damaged. After my grandmother was deported the Hungarians who had lived there were accommodated in my grandmother’s house. They got frightened, since they noticed we were looking for something. The following day they left the house.

You see, when we returned in January 1945, everything was frozen. My brother went to the city, he told me exactly where he had buried the documents and I went to dig them up. I didn’t have anything else to dig with, so I tried to dig up that frozen soil with a knife. Those Hungarians who had moved in were watching through the window, and when they noticed that I was trying to dig up something, they said: ‘You know we took coal from the basement, and chopped wood, but they didn’t tell us it was yours. We had noticed that the soil here has been dug before. We took out some kind of special cans for fat’.

My grandmother had put something into those cans; we didn’t know what. I don’t know what they stole, because I don’t know what had been in there. ‘Look, they said, ‘we will return it to you’. They got frightened because they noticed that we had been digging, which meant we were looking for something. They thought we were suspicious of them. And the following day they left the house, so it remained vacant. Up until two or three years ago I have been collecting documents here and there. I dug up those documents that belonged to my brother, they weren’t damaged very much, the only damage was from the moisture. Sometime in 1959 we got a very small amount of money for that house.

My brother, who was a lawyer – a very rare profession at the time – was placed in the military administration of justice. He stayed in Novi Sad.

I only became a graduating student after the war. I left the army, and reported at the headquarters of the army in Novi Sad. It was in July or August 1945; when Tito 9 or the state issued the order that the war was over, and that everyone who had been a graduating student needed to be demobilized in order to go back to his studies. I went to the headquarters for demobilization. I handed over the papers to lieutenant commander Jure Mihajic, and later on I read in the newspapers that he had been a Yugoslav military attache in Bucharest. He told me: ‘Stay here and help me with demobilization.’ I stayed another six weeks to help with demobilization because at that time, being a graduating student was much more rare than today. I demobilized hundreds in order to help my lieutenant commander. He was an honest person.

In Belgrade I stayed in the Jewish students’ dormitory. I stayed there from the first day up until I received the papers for my diploma. No doubt, I would have stayed in Belgrade after graduation, but I didn’t have an apartment, and in those times getting an apartment was something you could only dream of. Then I left for the countryside. I stayed and I worked here and there. I came to Novi Sad, because an opportunity arose to come here and also to get an apartment.

I wasn’t a member of the Communist Party, and my opinion about the regime was the same as everyone else’s who didn’t stand out politically. I could never stand Stalin, and even though I was still a child, I remember those trials in Russia [during the so-called Great Terror] 10. They always seemed vague to me. All of Stalin’s associates, at the time, became spies and agents of foreign countries, which, even as a child, I didn’t like. Then, when he made a treaty with Hitler on the eve of the war, he caused trouble, and I had enough of him once and for all.

I cannot say that I had problems only because I’m Jewish. I’ve always had problems. I had problems because I wasn’t a party member, it wasn’t a plus at that time not being a party member. Probably I could have achieved more if I had been in the Party, but it didn’t bother me. I went to our village to see if we could get any money for the house, since it hadn’t been nationalized but expropriated for some more important needs of society.

The house had been demolished and they ordered a small amount of money to be paid. Those times even that little money meant a lot for me. I went to the party secretary. First they told me that he was in a meeting, but when he heard that I had come from Novi Sad, he came out. He was a short person. I told him that he should pay for the house. He was first looking at me and then said, ‘What do you want? You should be happy that you stayed alive!’ I became angry and wanted to hit him. It was the time of the Informburo Resolution 11 and he would have filled me with more holes than Swiss cheese has, so I only swore at him and left. It was an anti-Semitic incident, other than that I didn’t experience anti-Semitism.

After I graduated from university I got married and then my wife Vera and me left because I didn’t have an apartment in Belgrade. A year later I went to the village and stayed exactly five years. I came to Novi Sad in 1947 and I’ve been here since. It has been 46 years. I was a doctor and I practiced.

I’m in my second marriage now. My first wife, Vera, was Serbian. As most Serbs, she spent the war at home in Srem [southern Voivodina, the area in between the Danube and the Sava rivers]. My daughter, Olga, is from my first marriage. From my second marriage I don’t have children.

My second wife, Ana, was born in Novi Sad. She worked in the hospital. I never met her parents. We are both retired now. I work in the Jewish community as much as I can. I used to hold some positions in the community.

I’ve always had an exceptional pro-Israeli disposition, and I still do today. I’ve been in Israel 13 or 14 times so far. My wife worked in Israel for about four months after she retired. It happened by pure chance that we both got jobs in Israel, so we both worked there, at the Dead Sea.

Our daughter, Olga, has partly been raised Jewish, and she says she identifies herself as a Jew. She was born in Belgrade on 2nd August 1952. She has lived in Novi Sad ever since kindergarten. She finished medical school, specialized in biochemistry and worked as a biochemist in the laboratory of the medical faculty. I don’t have any grandchildren.

I’m a doctor and I’ve practiced my profession. I wasn’t religious since I was raised in the youth movement Hashomer Hatzair 12, and it wasn’t a religious organization. I served in the army towards the end of the war, for only a few months. I’m bilingual; my mother tongues are Hungarian and Serbian. Apart from that I also speak German, and a little bit of English.

After the fall of communism nothing has changed, when the Berlin wall was brought down, nothing essential has changed. We are a secular community, and have no particular religious life. Rosh Hashanah and holidays were celebrated though.

It’s difficult to say why I didn’t emigrate to Israel. I don’t know why I didn’t go. My brother thought that he had no perspective there as a lawyer. I had only been a student then, what would I have done there? He didn’t go, I didn’t go either.

I have received assistance from the Swiss compensation fund and from the Claims Conference.