Sophia Vollerner

Chernovtsy

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: January 2003

Sophia Vollerner lives alone in a small two-bedroom apartment in the center of Chernovtsy. She keeps her apartment ideally clean and tidy. She has a big collection of books: Russian, Jewish and foreign classics as well as modern writers. Sophia is very fond of reading. She is 92 years old, but one would never think of calling her an old woman. Sophia is an amazing old lady of straight bearing, thoroughly dressed, wearing some make-up and a neat hairdo. She is very friendly and dignified, has a nice way of speaking and a wonderful memory. The only subject that displeased her during the interview was politics. She has never taken any interest in political events and she explains that politics stir a feeling of disgust in her. Sophia has problems with her legs and can only go outside in warm weather.

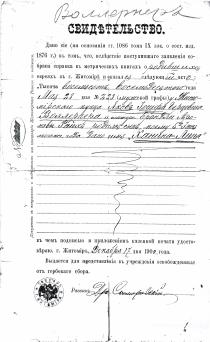

My father's parents came from Zhytomyr. My grandfather, Yankel-Joseph Vollerner, was born in 1830. He was a slim man and about 165 centimeters tall. He had a small beard and wore black clothes. He wore a black silk yarmulka at home and when going out he put on an ordinary black hat. He was a merchant of Guild II 1, I believe. I don't know what exactly he dealt with. In my father's birth certificate, issued by the rabbi of Zhytomyr, it is written that his father was Jacob Joseph Hertzevich Vollerner, a merchant of Guild II in Zhytomyr. My father's mother, Brandl Vollerner, nee Raikh, was his second wife. She was much younger than my grandfather. She was born in the 1850s. My grandmother was a housewife. My father told me that Grandmother Brandl was beautiful. When I remember her she was a fat woman of average height. She was short of breath. My grandmother didn't care much about the way she dressed. She usually wore dark, long and loose clothes. She wore a shawl and she always had a wig on under the shawl. They had a house in Zhytomyr. I've never seen this house. My father told me that his parents lived in the central street in Zhytomyr in one of the biggest houses in the town.

Zhytomyr was an old town, 200 kilometers from Kiev. At the beginning of the 20th century its population was about 100,000 people. From the middle of the 16th century to the 18th century Zhytomyr belonged to Poland and then it became a part of the Russian Empire. There was a Russian, Polish and Jewish population in Zhytomyr. Jews constituted about 30% of the population. They traditionally lived in the central part of the town and their neighbors were rich and intellectual Russian and Polish families. Jews were involved in crafts and trades. There were also wealthier families of Jewish intellectuals. There was a big Jewish community in Zhytomyr. There were no nationality conflicts. There were a number of synagogues in the town. Even after the Great Patriotic War 2 and the period of struggle against religion 3 there were five synagogues left. There was a cheder, a Jewish secondary and a yeshivah. The Jewish community paid much attention to charity and assistance to poor families and lonely elderly people. There was a Jewish orphanage, an old people's home and a Jewish hospital.

During the Civil War 4 there were pogroms 5 in the Zhytomyr. Various gangs 6 and Denikin 7 troops came to rob Jewish houses. The local people often gave shelter to Jewish families in their houses.

My grandparents had a big family. My grandfather had three children with his first wife. At least, I knew three children. His first wife died of a disease in 1872 and when the mourning was over in 1873 my grandfather married my Grandmother Brandl. I guess, they might have had more children, but only three reached adulthood. My father's oldest stepsister, Beila Barmat, nee Vollerner, was born in 1870. She had two daughters and three sons. They lived in Kiev. Beila was a housewife. My father's second stepsister, Reiza Cherniavskaya, nee Vollerner, born around 1872, lived in Kiev with her family. Reiza had a son and a daughter. Reiza was a housewife. I don't know what Beila and Reiza's husbands did for a living. I don't even know whether they had any education. I knew their children: they were all much older than I. Both stepsisters died in the late 1920s. My father's stepbrother, Isaac Vollerner, was the youngest in the family. He was married and lived in Radomyshl near Zhytomyr. I don't know what he did for a living. Isaac perished during a pogrom in Radomyshl in 1916. I have no information about his family.

Emanuel, born in 1875, was the oldest of my grandfather and grandmother's children. The next child was Moisey, born in 1876, and my father, Philip, followed on 28th May 1880. He was named Khanin-Liepa at birth. The youngest Maria, or Mariam, was born in 1890.

My grandparents were religious. They observed Jewish traditions, observed Sabbath and Jewish holidays and followed the kashrut. I know about it from my father, but I don't remember any details. My grandfather and grandmother went to the synagogue on Sabbath and Jewish holidays: they had seats of their own there. They raised their children religiously. My father and his brothers studied at cheder. They started their education when they were six. Maria had a teacher at home. She studied Hebrew, the Torah and the Talmud. They spoke Yiddish in the family. They also had a good conduct of Russian.

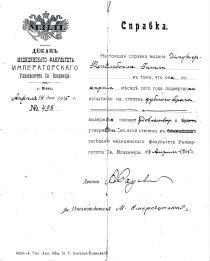

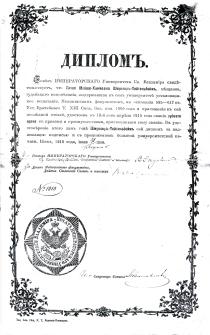

My grandfather believed it was important to give education to his children. They got traditional Jewish education and at the same time they finished Russian grammar school in Zhytomyr. After finishing grammar school all of them, except Moisey, studied at dentistry school in Kiev. I don't know why they made this choice. Probably, there were fewer restrictions for Jews to study at this school. [The interviewee is referring to the five percent quota.] 8 They studied for four years at school. After finishing this school they passed a state exam at the Medical Faculty of the Royal University of Saint Vladimir to receive a doctor's diploma that gave them the right to practice medicine. Moisey entered Medical Faculty of Tallinn University [today Estonia].

Before the [Russian] Revolution of 1917 9 Jews weren't allowed to live in Kiev due to residential restrictions [the Jewish Pale of Settlement] 10. The only exception was made for craftsmen, merchants of Guild I & II, doctors and their families, who were allowed to settle down in Podol 11, in the old central neighborhood of Kiev. When my father studied in dentistry school my grandparents sold their house in Zhytomyr and moved to Kiev to be near their children who studied and lived in Kiev. They settled down in Zhylanska Street in the center of the town. They rented an apartment. My grandfather continued his work as a tradesman and my grandmother was a housewife.

My father and his sister Maria stayed in Kiev after finishing their studies. Maria married my father's fellow student and friend, Isaac Tetelbaum, after finishing her studies. Her husband was a dentist and Maria was a housewife. They had three children. Isaac had extensive private practice, and the family was well-provided for. My parents and Maria's family were friends; they often went to see each other. Maria's family observed Jewish traditions and Jewish holidays. Maria died in Kiev in 1940. Her children passed away, too.

My father's brother Emanuel moved to the town of Malin near Zhytomyr after finishing his studies. He got married there and had three children. I saw Emmanuel's family once or twice in my life when I was a child, when they visited Kiev. I don't remember his wife or children's names. My father corresponded with his brother, but I don't remember any details. Emanuel died in Malin in the 1970s.

Moisey came to Kiev after graduating from Medical Faculty of Tallinn University. He was a well-known venerologist. Moisey married a Jewish girl, but had no children. His wife was also a doctor. We didn't see him often. His family visited us on birthdays of members of our family and we visited them on Moisey and his wife's birthday. Besides, we met with Moisey and his wife at my grandparents' home on Jewish holidays. I don't know whether Moisey was religious, but he visited his parents on Jewish holidays. He was a doctor in Kiev. He provided well for the family. He died in Kiev in the 1960s.

My father rented an apartment in Slobodka 12 located on the left bank of the Dnieper on the outskirts of Kiev. Nowadays this part of Kiev is a huge housing area. My father had a private dentist's office in his apartment. In 1908 he met my mother, Clara Tetelbaum, the younger sister of his sister's husband, Isaac.

I know very little about my first mother, as I call her. Her parents lived in Tulchin, a small town in Vinnitsa region. I've never been there, but I believe it was no different from other small Ukrainian towns where a significant part of the population was Jewish. My mother's father's name was Joseph Tetelbaum. Her mother's name was Nehama. I don't know her maiden name. They owned a store. I don't know any details about their life. I know that her family was religious. My grandmother Nehama wore a wig, long dark skirts and long-sleeved blouses. They had five children.

I know my mother's date of birth and also that the other children must have been born every second year. Meyer, the oldest, was born around 1880. The next one was Isaac, born around 1882. Moisey followed in 1884 and Malia in 1886. My mother, the youngest, was born in 1888, her Jewish name was Khaya. All children got religious and secular education. Regretfully, I don't have any details about my mother's childhood. My mother died when I was a small child and I know very little about this period of her life.

Isaac and Moisey stayed to work in Kiev after finishing the dentistry school. Meyer was a clerk and lived in Odessa with his wife and two children. During the Great Patriotic War Meyer and his family were in evacuation in Kazan. He fell ill and died in 1942. Isaac died of a disease during evacuation in Tashkent in 1943. Moisey lived in Kiev. He married a Jewish girl and had two children. In September 1941 Moisey and his family were killed by fascists in Babi Yar 13 in Kiev. After Malia got married to a Jewish man she lived in Pechora, Vinnitsa region. She had two children. Malia came to Kiev to visit her relatives and she perished in Babi Yar, too. During the war there was a death camp in Pechora. We found no information about Malia's family after the war. They must have all died in the death camp.

My mother studied in a grammar school in Kiev. I guess she met my father through her brother Isaac who was married to my father's sister Maria. After finishing grammar school she left for Odessa and stayed with Grandfather Joseph's brother, Moshe-Khaim Tetelbaum, and his family. My father came to see her there and proposed to my mother. They got married in 1909. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with a chuppah. They had their wedding in Tulchin where my mother's parents lived. After the wedding the newly-weds came to Kiev. My father worked as a dentist and my mother was a housewife. I was born on 31st October 1910. My father told me that I was given the Jewish name of Shyfra after my great-grandmother. Nobody ever called me by this name, though. I've never seen my birth certificate issued by the rabbi and in my passport I had the name of Sophia written.

My father had success with his work and in 1911 we left Slobodka for the more prestigious right bank of the Dnieper. My father rented a big apartment on Kreschatik, the main street in Kiev. He had a dentist's office in this apartment, too. My younger brother, Naum, Nakhman in Yiddish, was born in April 1913. My father told me that my brother was born during the first seder at Pesach that my parents celebrated with the family of Grandfather Yankel in Zhylianskaya Street.

Our apartment on Kreschatik Street was in a big three-storied house. This house was ruined during the Great Patriotic War. Today the building of Kiev Town Hall is situated at the place where our house was. There were five or six different shops on the first floor and a printing house on the second floor. Grigorovich-Barski, the owner of the printing house, was also the owner of the house. He was a Russian man. There were two apartments on the third floor: one was ours and another one belonged to a photographer called Excelrod and his family. They weren't Jewish: he was Polish and his wife was Russian. My parents got along well with them, but didn't visit them. My brother and I and their two daughters were friends and we visited each other; they were our best friends. Our neighbor's photo-shop was also in his apartment. We often visited our friends, but we were just kids and weren't allowed to go inside the photo-shop.

My father had two rooms that he equipped as his practice. There was a boy who opened the door for my father's patients. My father had various clients. They were people of different nationalities. For the most part they were wealthy clients that could afford to pay the price of dental services. My father didn't allow my brother or me to come into his office. Therefore, I cannot describe what it looked like.

We had a living-room with two sets of furniture: a set of soft furniture with upholstery of green and a Viennese set. There was a table, chairs and a carved cupboard in the dining-room. My parents had nickel-plated beds with nickel balls on the posts in their bedroom. In the children's room we had the same beds, only smaller. We had nice china and carpets. I don't remember any pictures on the walls, only the portrait of me and my brother. Our neighbor photographed us. This portrait disappeared during the Great Patriotic War. My father had a study-room where he read in the evenings. There was a kitchen, a bathroom and a toilet. We had a baby-sitter and a cook. They were both Russian women. We were a wealthy family.

My parents spoke Russian and only switched to Yiddish when they didn't want their children to understand the subject of their discussion. I learned to understand Yiddish, but I cannot speak it. I learned to read Russian before I turned five. We had a big collection of books. My father subscribed to the supplement of Niva magazine, which issued Russian classic books. We had many books in Hebrew and Yiddish in solid binding with golden stamping. My father read these books.

From the time I learned to read I spent most of my time reading and even burst into tears when my nanny took me for a walk. When I turned six my nanny was replaced with a governess, a Russian woman. She was a beautiful, slender, fair-haired woman wearing dark gowns. She seemed very strict to me compared to my nanny. The governess taught me French, French verses and children's songs that we sang together. I have more clear memories of my life from that time. There were several instruments in the house: a piano, a violin, a mandoline and a horn. My father could play them well and enjoyed playing. I don't know where or when he studied music. Sometimes he arranged family concerts and sometimes he played just for himself quietly in the evening. He said that it was the best rest for him.

My mother died during the epidemic of Spanish flu in 1915. She was buried in accordance with Jewish traditions in Lukianovka Jewish cemetery 14. In 1916 my father married my mother's cousin, Gitlia Tetelbaum. I've never called her stepmother, not even in my thoughts. My brother and I called her our second mother. Gitlia's parents lived in Tulchin before they moved to Odessa in the 1910s. I don't know why they moved. Gitlia's father, Moishe- Haim Tetelbaum, was my paternal grandfather's brother. He was born in Tulchin. All I remember is that he was much younger than my grandfather. I remember Gitlia's mother, but I don't remember her name. She didn't wear a wig or a shawl. She had beautiful thick wavy hair that she wore in a knot. In summer she wore hats. I visited her several times during my summer vacations. Gitlia looked much like her mother. They owned a small store. They had seven children. I don't know their dates of birth. The oldest son's name was Meyer, then came David. Gitlia was born in 1892, then came her two brothers, Isaac and Matvey, and two sisters, Eta and Clara.

All children got education. All the brothers, except Isaac, were accountants in offices. Isaac and Gitlia finished dentistry school in Kiev where my father studied. Clara graduated from the Pharmaceutical Faculty of Odessa University. She was a pharmacist. Eta married Rabinovich, a Jewish man. They had two children. She lived in Vinnitsa with her family and was a housewife. During the Great Patriotic War Eta and her family perished in a ghetto in Vinnitsa. Jewish ghettos spread all over Vinnitsa region. This area was called Transnistria 15. Moisey died of a disease in evacuation during the Great Patriotic War. All others lived in Odessa after the war. They died in Odessa in the 1960-70s.

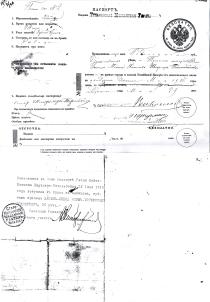

According to Gitlia's passport, signed by a rabbi, 'Gitlia Tetelbaum, a 24- year-old, dentist, married on 22nd June 1916 Khanin-Liepa Vollerner, a 36- year-old widower, dentist'. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with a rabbi and a chuppah arranged by Gitlia's parents in Odessa. After the wedding the newly-weds moved to Kiev. Gitlia was a housewife and a loving mother for me and my brother. She didn't have children of her own.

My parents weren't particularly religious, but they observed Jewish traditions. They didn't follow the kashrut. I remember that when my grandfather Yankel came to visit us Gitlia showed him dishes for dairy products and for meat products, but she just pretended that we had separate utensils. We always celebrated Sabbath at home. Gitlia lit candles and said a prayer. We prayed for the health and wealth of our family and relatives and sat down for a festive dinner. However, I don't remember that the family followed the ban to work on Sabbath. A Christian cook did the cooking on Sabbath, so it wasn't necessary to make food for two days.

On holidays my parents went to the synagogue. My father fasted at Yom Kippur, but he didn't stop smoking on these days. We observed Jewish holidays at home. My father believed that my brother and I had to know traditions. We had matzah at Pesach and didn't eat bread on these days. There was a major clean-up of the house, but I don't remember looking for breadcrumbs with my brother. We had special dishes for Pesach that were kept in a cupboard. There was traditional food at Pesach: gefilte fish, chicken broth and matzah pudding with eggs and potatoes. There were strudels with jam and raisins, honey and sponge cakes. There were greeneries, a boiled egg and a saucer with salt water on the table. There were tall silver glasses on the table: my mother's dowry.

There were always four of us on the first seder at Pesach: our parents, my brother and I. During the seder adults drank four glasses of wine. My brother and I drank water with a few drops of wine in it. There was one extra glass for Elijah the Prophet 16 on the table. In the evening my father always conducted the seder. He said all the necessary prayers. I can still remember the words of these prayers, but I don't know the meaning. My brother posed the four traditional questions [the mah nishtanah] that my father had taught him. Our father broke a piece of matzah and my brother or I had to steal one piece [the afikoman] and hide it. I usually let my brother do it since he was younger. Later he gave it back to our father for a small ransom: a candy or a toy.

My father didn't make a sukkah at Sukkot since we lived in the central street of the city, but we always had fruit that grew in Israel. At Chanukkah our parents gave us money. At Chanukkah Gitlia lit one candle each day in a big bronze chanukkiyah. At Purim my father read the Book of Esther to us and told us the story of evil Haman and brave Mordecai who rescued Jews from a terrible death. We also celebrated birthdays with relatives and friends. They were all Jews. My parents got together with their Jewish relatives.

After the Revolution of 1917, during the Civil War, there were Jewish pogroms in Kiev. They happened on the outskirts of the town: Demeevka, Solomenka and Podol. My father was rather loyal to the Revolution of 1917. He wasn't quite enthusiastic about it, but there wasn't open aversion on his part either. He was critical about the new regime, but I guess my father accepted the Revolution as a reality that couldn't be changed. Fortunately our family didn't suffer. After the Revolution my father even continued practicing medicine. Of course, we were 'compacted', so to speak, that was a usual process at that time. There were other tenants accommodated by the authorities in our apartment, but I don't remember those people. My father took it easy since it was a common practice at that time. We only had my father's office, the bedrooms and the living- room left. It wasn't a big change for me. We had the same furniture and it was our home, only smaller. We had our housemaids helping us with the housework, who stayed with us until the Great Patriotic War.

After the Revolution there was the time of the Civil War when various authorities were in power. I remember the power taken over by Petliura 17 troops. There was a parade that we could watch from the balcony. Then there was firing between Petliura and Denikin troops arguing about which flag should be hung on the Town Council building.

My grandfather Yankel died in 1920. He was buried in accordance with the Jewish traditions in the Jewish cemetery in Kiev. My father recited the Kaddish over his grave. Every year my father had a remembrance ceremony for him conducted at the synagogue. I remember that each year he took honey cake and vodka to this ritual. My grandmother Brandl died in 1930 and was buried beside my grandfather's grave.

I passed the exam to the senior class of grammar school in August 1917. I was well-prepared and had no problems with the exam. Gitlia was a good teacher. She was good at mathematics and physics and could explain difficult things in an easy way. After the Revolution the grammar school became a secondary school. The school was round the corner from our house; I didn't even have to cross the street. Later my brother went to the same school. All life long we were very close to each other, but at that time I was always angry with him since he followed me everywhere and it really got on my nerves. He wanted to be closer to his older sister, and he courageously tolerated my mocking. My brother and me had the same teachers and the majority of schoolchildren were children of the intelligentsia. There were many Jewish children. I don't remember any instances of anti- Semitism. I had Jewish and Russian friends. With some of them I stayed friends all my life. All of them have passed away already.

My favorite subject at school was Russian literature. Reading was everything to me. Gitlia wanted me to study music. To stimulate me she made a deal: an hour of music for an hour of reading. During my music hour there couldn't have been a more serviceable and compliable girl in the world: I rushed to help everywhere, helping to find keys or open the front door when the doorbell rang. But when I read I wouldn't have noticed if the walls had fallen down. I was hiding the books in the toilet. My mother Gitlia noticed that I went to the toilet too often and began to take the books out of my hiding places. Generally speaking reading prevented me from learning to play the piano. It was my biggest hobby that stayed with me through my life. I read whatever I got hold of.

At school I became a pioneer. I liked it. A red necktie, pioneer saluting and marching attracted me. During the admission ceremony we took an oath to be devoted to communist ideals. I remember how on the appeal 'To struggle for the cause of workers and peasants be ready!', we answered in chorus, 'Always ready!'. There were pioneer groups in various institutions. I, for example, was a member of the pioneer group at the House of the Red Army. We were engaged in sports, prepared political reports on the international situation. We celebrated all revolutionary holidays. We went to parades with red flags. I have dim memories about this period, though. We didn't celebrate revolutionary holidays at home. Later I didn't join the Komsomol 18 or the Communist Party. I stayed away from politics my whole life. I had an equally negative attitude to public activities.

In 1923 my father hired a teacher for my brother and me. We had private classes three times a week. He was a relatively young man with a small beard. He didn't have payes. I remember I was surprised that he didn't take off his hat when he entered the house like other visitors did. He kept his hat on even during our classes. He taught us Hebrew, Jewish traditions and history, the Torah and the Talmud. We studied for two years. I guess my father wanted to prepare my brother for his bar mitzvah. I can still remember many words in Hebrew, traditions and rituals.

I finished secondary school in 1925. At that time the educational system was different from now. There were seven years of studies at secondary school, then students went to trade school where they studied general subjects and got professional training. I went to a cooperative school. My father paid for my education. My brother went to an electro-technical trade school. Training in trade schools lasted two and a half years. After trade school students could enter an institute where they studied for three and a half to four years. It was an intensive course since the country needed experts. In trade school we studied mathematics, two foreign languages - English and German - and literature. Besides, there were special subjects: commercial arithmetic, commodity research and law. Such schools issued a certificate and diploma about professional training. They were much like modern colleges. I had very good company at school: three girls and three boys. Out of the six of us one girl was Russian, the others were Jews. We were all fond of literature. We read a lot, discussed books and tried to write verses. We went to theatres and to the opera.

My father began to work as a dentist in a military unit. He had a permit for private practice issued by the financial department. However, he had to work for the state as well since my brother and I had to submit certificates about his place of work when entering the institute. I finished trade school in 1928, and in the same year I entered the Faculty of Economics of Kiev Trade Economic Institute. My parents insisted that I went to study at the Medical Institute, but I didn't have the slightest intention of doing that. I was sick and tired of listening to medical discussions at home. I wanted to study at the philology department, which was called Faculty of History and Philology, but many people were telling me that they studied works by Stalin for the most part and that was true.

My brother finished electrotechnical school two years after me and got a job assignment in Sverdlovsk. He worked for the standard three years before he returned to Kiev and entered the Faculty of Radio-Engineering of Kiev Polytechnic Institute. From then on his life was always connected with the Polytechnic Institute. After his graduation my brother stayed for postgraduate studies and lectured at the institute. Before the Great Patriotic War he defended his candidate dissertation and shortly after the war he defended his doctor's thesis.

There were about five students in my group from trade school who entered the Faculty of Economy, section of Trade and Economy, of Kiev University; the rest of the students entered the institute after working for several years to get work experience. They had admission privileges. Most of them were from villages, and we, city girls, were more refined in manners, culture and behavior, but we got along well with them. During my studies at the institute, I didn't feel any anti-Semitism. I don't mean to say that there was no anti-Semitism at all at that time. It has always been there and it always will be as long as there are Jews and non-Jews on Earth, but I personally never faced any.

I met my future husband, Alexandr Andrievskiy, during my studies at the institute. We studied in the same group. Alexandr was born in the town of Kakhovka, Odessa region in 1905. His family moved to Pervomaysk, Odessa region. My husband's father, Vassiliy Andrieskiy, was a railway man, and his mother, Barbara Andrievskaya, was a housewife. Alexandr's father died when he was still young and his mother raised four children on her own. She also managed to give education to her children. She earned her living by cooking dinner for people who hadn't enough money to go to restaurants. The oldest daughter, Antonina, was a teacher, Grigory was chief accountant in an office and Evdokia was a doctor. My husband was the youngest. After school he was a secretary of the district committee of the trade union, and from his management he got the order to study at the institute.

We got married after graduation. I kept the last name of my father in marriage. My husband was Ukrainian and my parents were against this marriage: it wasn't Alexandr they were against, but that I married a man of a different religion. Especially my mother was against our union. She said she would understand me, if he was an aristocrat or a very rich man. But I married a villager. She also kept telling me that all relatives might think that she treated me so badly that I hurried into marriage with the first man who crossed my way, only to escape from her. There were many tears, disputes and arguments. When I told my parents that I loved Alexandr and wasn't going to turn him down my parents terminated their relationship with me. Alexandr and I had a civil ceremony at the registry office and I went to live with my husband. I left my parents' home with a small suitcase. My parents didn't give me any books or clothing and my father said to me that I would be back home anyway after the divorce.

My husband's family welcomed me heartily. His sister, Evdokia, came to Kiev before we got married. We became friends. A year later my husband and I went on vacation to Pervomaysk where I met his mother and sisters and brothers. My mother-in-law always treated me like a daughter and was trying to help wherever she could. We corresponded very actively. She was a common, but very kind and wise woman.

It took some time to improve our relationship with my parents. I wrote them greeting cards on family and Jewish holidays. For almost two years my letters returned unopened to me before my parents began to respond. I corresponded with my brother regularly. In 1932 my husband was in Kiev and went to see my parents. They were very arrogant at first: they wouldn't have let him in had it not been too rude. When they got to know him better they changed their attitude and realized that he was a decent man. From then on my parents treated us like their beloved children.

I didn't observe any Jewish traditions after I got married, although my husband was very tolerant to other people's faith. When we visited my parents at Pesach he did everything in accordance with the rules. I belonged to a younger generation that was forced to believe that there was no God. I was sincerely convinced that religion was to vanish with my parents' generation. However, I always identified myself as a Jew and even emphasized my Jewish identity. Once my husband and I visited a family and the mistress of the family spoke disrespectfully about someone. 'Ah, but he is a Jew!' she said. I immediately said that I wasn't going to stay for another second in that house and left. My husband followed me and we stopped seeing this family.

My husband and I got a job assignment in Gorlovka, Donetsk region, 500 kilometers from Kiev. We stayed in different hostels until we got a room in a two-bedroom apartment. Only after our son was born we received a two- bedroom apartment. I worked at the Mechanics of Donetsk cooperative and my husband worked at a mine. I went to work at a bank in 1932. I believe anti- Semitism in Donetsk wasn't as strong as in Central and Western Ukraine. We didn't suffer during the period of the famine in Ukraine 19 from 1932-33. There were food supplies to Donetsk and we had food product coupons for all the necessary products. We shared food with our parents, who lived in Kiev.

My parents were very happy when their grandson was born in Gorlovka in 1933. We named him Rostislav. I had maternity leave for two months before I had to go back to work. My mother-in-law came to us after Rostislav was born. My husband hired a housemaid and my mother-in-law looked after Rostislav. She stayed with us until 1937. She was a reliable and loving grandmother to our son.

I was content with what we had in life. I never wanted more than we had. The biggest luxury for us were books and we collected books from the very beginning of our life together.

The arrests that began in 1936 [during the Great Terror] 20 and lasted until the beginning of the Great Patriotic War didn't affect our family. Our colleagues and acquaintances suffered, though. In the bank where I worked somebody was arrested every day. My husband and I never discussed this subject; I was living in a state of stupor during this period. I went for advanced training in Kiev in 1937 for six month but I didn't take my son with me. My mother-in-law took him with her. My husband had to stay at work in Gorlovka. After my training was over I stayed for practice at the State Bank of Ukraine. My father worked a lot, and my mother wasn't well. During my stay in Kiev I lived with my parents in our apartment.

Hitler coming to power in Germany and the following events, the Soviet- Finnish War 21 and the occupation of Poland in 1939, didn't attract my attention whatsoever. I thought it had nothing to do with us. Even in 1939, it never occurred to me that Hitler might attack the USSR.

In 1940 Bessarabia 22 and Moldavia [today Moldova] joined the USSR. Before they joined the USSR my husband went to Chernovtsy as a member of governmental delegation. In July 1940 the Ukrainian Ministry of Trade sent my husband to work in Chernovtsy. In September I was transferred to work at a bank in Chernovtsy at my request. I took my son with me. We got a nice three-bedroom apartment in the center of the town. Our son went to school in Chernovtsy. We liked Chernovtsy. It was an old beautiful town. Many people spoke Yiddish in the streets. There was a big synagogue and several smaller ones, a Jewish school and a Jewish theater. Before the Great Patriotic War the majority of the population was Jewish. There were no conflicts and people treated each other nicely.

The locals didn't really welcome the newcomers: they called us 'Soviets', but I didn't feel any prejudice on my part. Many people spoke German. Before 1918 this area belonged to Austro-Hungary and since then German was as common a language there as Romanian. They addressed me in German in the streets taking me for one of them. My husband felt at home very soon after we moved. He made friends with the local Bessarabian men that spoke fluent Russian. Alexandr was chairman of the trade union of workers. When he had to speak at a meeting I wrote a speech in German in Russian letters. People appreciated his respect of their language and traditions. There was a difference between the newcomers and local people. One could tell the difference at once at a theater, for example. I saw women wearing nightgowns with lace and embroidery to the theater. They must have taken them for evening gowns. Many of those that moved to Chernovtsy made an impression of wild and ignorant people that were buying everything they saw in stores. It could be understood since many officials in the USSR were peasants or workers with little or no education. A colleague of mine once told me with indignation that one of those newcomers didn't know who Schiller 23 was. I replied with a smile that it was no wonder since that person didn't know who Pushkin 24 was either.

At the beginning of June 1941, my son and I went on vacation to Kiev. My husband stayed in Chernovtsy. On the morning of 22nd June 1941 my father went to the market. He returned in no time and said that there was the sound of bombing in the town. I thought it was another military training. Later the janitor of the building dropped by saying that German planes were bombing the airport in Zhuliany, on the outskirts of Kiev, and it was war. We turned on the radio and heard Molotov 25 speaking. They announced on the radio that vacations had to be terminated and everybody had to come back to work.

Discipline at work was very strict at that time: one could get arrested for coming to work ten minutes late. I ran to the railway station to get tickets to Chernovtsy. My father and mother begged me to stay, but I was afraid to violate the discipline. There were no tickets sold in Western direction at the station. I cried and begged the cashier to sell me one, but they were just looking at me as if I were crazy. So I failed to leave. In about a week's time my husband arrived. My parents didn't even consider evacuation. They were telling us how nice Germans had been during World War I. My mother was of the same opinion. They refused to go. Many people went into evacuation with the companies they worked for. I went to the office of the State Bank and they issued a permit for me and my son to evacuate with a group of bank employees to Voronezh.

My husband wasn't recruited to the army immediately since his military identity card had been taken for re-registration shortly before the war. He had a certificate issued to confirm identity. After we left to Voronezh, my husband went to a military registry office where he was appointed logistics manager in a hospital. This hospital was in Lisky and later moved to Saratov. At the end of the war the hospital moved to Uzhgorod in Subcarpathia 26.

My parents followed us in three weeks time. Their train stopped in Lisky in Russia, 800 kilometers from Kiev. My mother had a picture of my husband and she went to the local military registry office looking for him. She managed to convince an officer of the registry office to give her the address of the hospital. They weren't allowed to give any information to outsiders. My mother found Alexandr and he gave her our address. My parents managed to find us and joined us in Semiluki, near Voronezh in the central part of Russia [1,000 km from Kiev]. We stayed there for some time until my husband arranged for us to move to the Ural. My brother was a consultant at a tank plant. He was in evacuation in Sverdlovsk region in the Ural. My brother got married shortly before the war. His son, Alfred, was born in 1941. He was in evacuation with his wife and their baby boy. The plant was evacuated to Egorshino, near Sverdlovsk, 2,500 kilometers from home. We went there by train.

It was a freight train for cattle and there were no comforts whatsoever. We slept on the floor. The train was so overcrowded that we all had to turn around at the same time at night. When the train stopped at a station, all people ran to the toilet and to get some food or water. We got off in Chkalov and from there we moved by vehicles to Sverdlovsk, 500 kilometers from Chkalov. We stayed at the railway station in Sverdlovsk for two days. I went to Sverdlovsk regional bank office and they gave me a job assignment in Alopaevsk near Egorshino where my brother was working. In Alopaevsk we got accommodation: two rooms and a common kitchen in a local house. There were four of us: my father, my mother, my son and I. The carpenter of the bank where I was employed made three beds, a cupboard and a few chairs for us. I worked at the bank and my son went to school.

I got two suitcases with the most necessary things from Kiev. My husband and my parents brought us some of our clothes. My mother had sent the rest of our luggage from Kiev before she went into evacuation and we were amazed that it was delivered to Alopaevsk. We exchanged things for food and I even joked that I would write a book called Theory and Practice of Exchange Operations. We often got vodka for our food coupons and my father exchanged it for bread. We weren't starving. Of course, we didn't have plenty to eat, but what we had was sufficient. I used to put a loaf of bread on the table for some time after the war for the family to see that we didn't have to save bread and that they could have as much as they wanted.

There were two or three plants in evacuation in Alopaevsk. People had their belongings with them and were dressed better than the local population. There was only one Jewish family in Alopaevsk before the war, but during evacuation many Jewish families came to town. Local people were jealous about their wealth. They were also angry that many local men were recruited to the front while so many Jewish men were staying in the rear. They didn't understand that only highly qualified employees were left to work in the rear and the rest had to go to the front. Those people believed that almost all the Jewish population of the country came to their town. They had a negative attitude towards us. I think this might have been the origin of postwar anti-Semitism when people believed that Jews were hiding from the war in the rear. I don't know whether my son faced any anti-Semitism at school. He never told me anything the like.

My mother died in Alopaevsk in 1942 at the age of 50. She was a sickly woman and had problems with getting adjusted to the local climate. We buried her in the town cemetery. There was no Jewish cemetery or synagogue in Alopaevsk. My father recited the Kaddish over her grave. After the war my husband and I had a gravestone installed on her grave.

My husband and I corresponded during the war. He joined the Communist Party during the war, which was a standard procedure. In November 1943 I got a holiday and went to see him in Saratov. At that time Kiev was liberated and they had a celebration at the hospital. In January 1944 my father, my son, my brother and his family and I returned to Kiev. In March 1944 the Soviet troops liberated Chernovtsy and in October 1944 I went there. My father and son were staying with my brother for some time until I came to take them to Chernovtsy.

There was another family living in our former apartment and I received a two-bedroom apartment near the bank where I worked. This was okay with me since I could walk to work from home. Later, when my husband returned, we got a bigger apartment. My husband demobilized in March 1946. The hospital administration offered him to continue his service in the army, but he insisted on demobilization. He became the director of a store in Chernovtsy.

There was a Jewish theater in Chernovtsy after the war. Actually, it was the Kiev theater that moved to Cherkassy. I used to go to their performances in Kiev. I attended performances staged after Jewish classics: Sholem Aleichem 27 and others. During the war the building of the theater was ruined and the theater moved to Chernovtsy from evacuation. All performances were sold out. The theater was very popular. It was closed in 1948.

There was anti-Semitism after the war. During the campaign against cosmopolitans 28 in 1948 anti-Semitism gained an 'official' [state] level. My brother defended his doctors' thesis shortly after the war, but it wasn't approved for several years. Jews had problems with entering higher educational institutions or finding a job. There was the expression 'invalids of Item 5' 29. I didn't have any problems, but my relatives and acquaintances did. Then the Doctors' Plot 30 came to life. We knew some doctors that were very concerned since they were losing their patients. There were many Jewish employees in the bank, but nobody got fired.

During the time of the Doctors' Plot and the death of Stalin in 1953 there was a rumor in Chernovtsy that Jews were to be deported to Siberia 31. My Jewish friends who had a Russian husband and I decided to go to exile together. I even packed my belongings to be ready to move. My friend and I were hoping that our families wouldn't have to go with us. My husband knew about my preparations and was very angry with me telling me off because I believed in this kind of nonsense. Later, in the 1980s, I got to know that there was such a decision made and only Stalin's death put an end to it.

On 5th March 1953 it was announced that Stalin had died. Before that day, they issued bulletins about his condition every day. 5th March was a day of grief for everyone. I cried my eyes out! I couldn't imagine that life might continue when Stalin was no longer with us. When Khrushchev 32 denounced the cult of Stalin at the Twentieth Party Congress 33, I didn't believe it at first. It was horrifying. Our idol was overthrown and there was no one to replace him. I think this was the time when people lost their belief in politicians.

My son Rostislav finished secondary school with a medal in 1950. We wanted him to study at the Medical Institute, but he was thinking about the Institute of Physical Culture. It was a nightmare for me to think that our only son would be a sportsman. He went to a sports school. He had a 23-year- old trainer that he idolized. My son got to know that he studied at the university by correspondence. Then Rostislav changed his mind and decided to enter Kiev Polytechnic Institute to study at the Metallurgical Faculty. Probably this decision was influenced by our life in Alopaevsk where my son had a friend whose father was a metallurgist.

When our son turned 16 he went to the passport office to get his passport. My husband and I didn't ask him any questions. When it was time for him to fill out the application form for the institute I asked him what nationality was written in his passport. He said it was Russian. I asked him, 'How come you are Russian when your father is Ukrainian and your mother a Jew?' My son said that he took this decision to hurt no one's feelings. Of course, my son was aware that his mother was a Jew, but he didn't care about it. There was an air of internationalism in our family.

Rostislav entered the institute without any problems. He graduated in 1955 and stayed on for his post-graduate studies. After he defended his thesis he got a job assignment to the Institute of Material Studies at the Academy of Sciences in Kiev. Rostislav got married to a Russian woman called Maria and his daughter, Elena, was born in 1960. Now she works at the Institute of Material Studies in Kiev. She finished her doctor's thesis and will be defending it soon. She is married, but has no children. Elena and I have good relationships. She often calls me. Rostislav's first marriage failed. In some time he got a divorce and moved to Moscow. He works in Chernogolovka near Moscow. He is a leading specialist in material studies, correspondent member of the Academy of Sciences, and a professor. Rostislav remarried and is happy with his second wife, who is also Russian. My son and his second wife have a daughter, Uliana. She was born in 1972. She graduated from the Institute of Chemistry in Moscow. She works as a chemist at a scientific research institute. Uliana is married and has two children. They are my great-granddaughters: Anna was born in 1999 and Alina in 2002. My son celebrated his 70th birthday at the institute recently.

My father died in 1968. He went to visit my brother in Kiev. He fell ill all of a sudden and my brother brought him to a recreation center, where my father died. The autopsy showed gullet cancer that had never disturbed my father before. We buried him in the Jewish section of the town cemetery in Kiev. There was a Jewish funeral.

My brother's son, Alfred, died of acute leucosis in 1969. He was such a nice man and talented scientist. He defended his doctor's thesis and was a lecturer at the Polytechnic Institute. Students liked him a lot and he spent much time with them. He was a very interesting man and had many friends. He knew a lot about music and liked literature. When he fell ill there were always people visiting him with the intention to help and support him. Regretfully, he was single. My nephew was buried near my father's grave. My brother and his wife Maya were desolate in their grief. Of course, our relatives and their friends tried to support them, but how could they ease the pain of their loss...?

In the 1970s Jews began to move to Israel. I sympathized with those that were leaving, but for me it was no issue. I've always identified myself as a Jew, but I belong to this country: my close relatives were buried here and my roots are here. I've had my happy and sad moments here. Besides, I didn't feel like changing my life so dramatically at my age, my son lived in another town and he was Russian, so he wouldn't have had any reason to go with us.

My husband died in 1976. He was buried in the town cemetery in Chernovtsy. My friends and books help me to make peace with my solitude. I gave my granddaughter Elena a big part of my book collection.

I retired from the bank when my time came in 1970. At last I could do what I liked and I became a librarian at the library in the bank. I didn't receive any salary for my work. It was like a public activity. I quit doing it in 1990.

When perestroika 33 began in the USSR in the 1980s I looked at it as just another 'action' of the Soviet power, but later my attitude changed. Of course, life has become more difficult in some respects, but on the other hand, our country became open. There is a freedom of speech that was just empty talk in the constitution before. There were books published that were forbidden before. There was an avalanche of information. One can buy any book at a bookstore now. Newspapers published articles about things that we weren't even allowed to think about. Anti-Semitism hasn't vanished from our lives. Even speaking about someone people have the tendency of saying, 'Ah, he is a Jew', regardless of the subject of discussion.

When Ukraine became independent in 1991 the Jewish life revived. I haven't gone out in ten years and I don't know any details about the life outside. In 1996 Hesed was organized in Chernovtsy. This organization became a part of our life. Jews like me, who are not so old yet, go there. Hesed became a center of Jewish spiritual life. Unfortunately, I haven't left my house in recent years. Hesed supports me a lot. I get food packages, meals and medications from Hesed. Doctors and volunteers from Hesed visit me. Whenever possible they take me to concerts or meetings. I still read a lot and it's my only entertainment. I wish I could read faster.

My brother, Naum, lives in Kiev. His wife died in 1994. My brother lectured at the Radio Engineering Faculty of Kiev Polytechnic University until 2000. Two years ago he retired, but he still works as a consultant. My brother got blind, but it doesn't have an impact on his work. He calls me once a fortnight and I always look forward to it. We have been friends for a lifetime. I celebrated my 90th birthday in the year 2000. My son and his wife and my granddaughters came to visit me on my birthday. There were many guests who said so many warm words that I would like to hear them on my next jubilee in ten years.

Glossary