Alexander Singer

Bratislava

Slovak Republic

Interviewer: Martin Flekenstein

Date of interview: December 2006

Mr. Alexander Singer is from a well-known rabbinical family, which before World War II was active in what is today Slovakia. He grew up in an Orthodox family, which paid strict heed to adhering to customs and traditions.

He received the highest possible religious education. But already before the war, it was clear to him that he, a rabbi's firstborn son, would not be following in his father's footsteps.

His decision saddened his parents, but they had understanding for their son. The tragedy of the Holocaust did not pass his family by either. Of his closest relatives, only his sister survived, who moved to the USA after the war.

She lives with her husband in New York, in a strict religious community. Their son also became a rabbi. Nor did Mr. Alexander Singer renounce his Judaism, despite the fact that he didn't practice it in such a devout spirit as before the war.

During the 1950s he was a leading member of the Jewish Religious Community in Jablonec nad Nisou, where he also led religious services. Despite his advanced age (90), he is vital, and even works part-time.

During our meetings he literally stunned me with his linguistic and religious learning. In my opinion, he belongs amongst those one could call a well of human knowledge and wisdom, and at the same time a pillar of Jewry and Jewish religious learning in Slovakia.

- My family background

All I can tell you about the origins of my ancestors on my father's side is that they were from Spain. Most likely, they were Sephardic Jews 1. The family's original name in Spain was Cantor. After leaving for Holland, they changed the surname to Singer. Both words mean the same thing, a singer.

I don't know if already back then there were rabbis in the family. My father's grandfather was named Jakub Singer. From 1858, he was the head rabbi in the town of Lucenec. At the beginning of the 20th Century, Lucenec was an important economic and cultural center. Orthodoxy 2 had a very strong influence in the town. It led all important establishments and associations in the town. The number of Jews in Lucenec in 1939 exceeded 2000, of whom 90% died during the Holocaust.

My grandfather was named Jisrael Singer. My grandfather's wife was Tereza, neé Ehrentreu. They lived in Bratislava. I don't remember my grandfather much. He died while I was still a small child. Originally he made a living as a businessman. Because he was a rabbi's son, and had more of a Talmudic education, he didn't understand business very much. He slowly went bankrupt.

Finally he became the rabbi of a small Orthodox community in Bratislava. The community's name was Torat Chesed. My grandfather was head of the synagogue, where each evening he lectured Torah and Talmud and led discussions with members of the community.

My paternal grandparents had four children. Two sons, David and Jakub, and two daughters, Sarolta and Foga. After my grandfather died, my grandmother lived with her daughters. She lived in a three-room apartment, on the second floor, at 1 Vysoka Street. She rented out two of the rooms, and used the proceeds to cover household costs.

The building belonged to the Büchlers, who had a large carpet store on the ground floor. The building stood where the Forum Hotel is today. Across the street was the Astoria Café. Every evening, there would be music being played in that café. My grandmother loved to sit by a half-opened window and sing to herself the operettas they were playing there. She was only sad in the winter, as the café windows were closed, and she couldn't hear the music.

After her husband died, my grandma was very poor, a pauper. She de facto lived on support she got from my father [Jakub Singer] and her daughter Sarolta. Sarolta worked as a sales representative for some company, which for a woman was very unusual in those days. She was very capable, but the poor woman died young due to her thyroid gland, in Vysne Hagy.

In the Singer family, Jewish customs and traditions were observed to the letter. My grandma's hair was cut short and she wore a wig. She also covered her head with a small decorative scarf, which also had little pearls crocheted onto it 3. Back then, all old devout women wore that. In her household, cooking was done according to ritual 4. Women didn't attend synagogue very much, just once in a while for the High Holidays. As our family didn't live in Bratislava anymore, my grandma was used to spending the High Holidays with her other son, David.

My mother's father was named Abraham Grünburg (1839 – 1918), and her mother was Rebeka, neé Weiss. Abraham Grünburg was the head rabbi in Kezmarok from 1874 until his death in 1918. I don't remember his name anymore. I was only two years old when he died. Up to the end of World War II, Kezmarok was a center of German culture in Spis [Spis: one of the region of Slovakia – Editor's note].

For a long time, the strong German majority prevented Jews from settling there. My grandfather had one son, named Nathan Grünburg, who became the town's new rabbi after his death, and the other son, whose name I don't remember was living in Csenger, a small town in Hungary, where he was a not very successful businessman, materially supported mainly by his brother Nathan.

At first Nathan refused the position of rabbi. He got married to some wealthy woman in Berehov. The way it actually was, was that after Grandpa died, my father, Jakub Singer, became the Kezmarok rabbi. But Nathan returned to his home town, and my father ceded the position of rabbi to him, because the custom was for the son to take over his father's position. Nathan was the last rabbi in that town. In 1944 they shot him in the Polish town of Zakopane. Before the war his community had around 1000 members.

Grandma Rebeka spoke only German. She died when I was a boy of about three, so I don't really remember her much. But I do remember one thing. Kezmarok was very poor, there wasn't any milk at all for the children. Close to Kezmarok, in the village of Lubica, there was one good-hearted farmer.

His name was Müller. Once, when I was a little child, he brought me milk in a small blue can. That then became a custom, and my grandma used to go get me milk every day. After she died, I started going for the milk myself. At that time I was only three, maybe four years old. Lubica was a couple of kilometers away from Kezmarok, but I didn't mind that.

The problem though, was that the farmer had two mean dogs. Because there were a lot of Gypsies living in the region, and they were all very poor and were forced to steal in order to support themselves. Well, and I was terribly afraid of dogs, because in town there weren't any.

I told my mother about it, but she answered me: "Don't be afraid, a dog that barks doesn't bite!"

"I know that, but I don't know if the dog knows it too!" is what I apparently answered back.

In those days, there were also a lot of Jewish immigrants from Poland living in Kezmarok. After the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy fell apart, they ran away to Czechoslovakia. This was because the Poles and Ukrainians were persecuting them en masse, pillaging their homes and stores.

They burned a lot of shtetls, towns. They even killed some of them. Polish Jews that settled in Kezmarok were mostly merchants, tradesmen, butchers, stonemasons. Stonemasons made matzeyves, gravestones. One of the Polish Jews was in charge of the ritual bath, the mikveh. He was called the Mikveh Yid.

His name was Östereicher. Jews in the town were also divided into Ashkenazim and Sephardim. Ashkenazim were mostly the original Jewish residents of Kezmarok, and Sephardim were immigrants from Poland. Immigrants were different in several basic ways.

Locals used to go pray at 6:00 a.m., so that at 7:00 a.m. they could open their stores and begin working. The Sephardim went to their synagogue at 8;00 a.m. Locals spoke mostly German, the immigrants Yiddish. The Ashkenazim dressed mostly the same as the rest of the population, but some of them had beards and wore black hats, while part of the Sephardim wore black caftans and black hats.

My father attended both synagogues. Some days he'd pray at 6:00 in the main one, and then on other days at 8:00 at the Sephardic one, and this in order to also show those members of the community that he was their man and that he respected their habits.

My father's name was Jakub Singer, and was from a rabbinical family, which is why he himself later became a rabbi in Samorín. His entire name was Abraham Jakob Koppel Singer, and his Jewish name was Abraham Jakov ben Jisrael.

My father was one of four siblings. He and his brother Chaim David were graduates of the world-renowned Talmudic school in Bratislava. The Sofer family taught at this yeshivah. The first one was Moshe Schreiber, known as Chatam Sofer 5.

Then, one after the other, his descendants taught there, it was always handed down from father to son, Ketab Sofer and Shevet Sofer. Shevet Sofer was also my father's teacher, and his son, Akiba Schreiber, was my father's classmate.

Before World War II, Akiba moved in time to Palestine, where he also moved the entire yeshivah. It's still active to this day, in the Mea Sherim quarter. My father and David attended this school together with Akiba Scheriber. They were very good friends. Akiba later recommended my father for the position of rabbi in Samorín.

This might be right time to mention an interesting anecdote that my father used to often tell me. My father was a very learned man. Besides other things, he spoke perfect German.

Due to the fact that he had good style and the appropriate knowledge, they entrusted him to welcome the Emperor Franz Joseph during his visit to Bratislava. During his stay in the city, Franz Josef also visited the synagogue in Zamocka St. Right at that time, a wedding was taking place in the courtyard.

The bride was standing under the chuppah, hidded under a veil. The emperor approached the bride, and was so bold as to look under the veil earlier than is permitted. He then stepped up to my father and whispered to him: „Kluge Sitten habt ihr Juden!“

That means: "You Jews have very wise habits!" Because the bride was terribly ugly. My father knew a song about an ugly bride: „Ich bin nit lang of a chaseneh gewen di kaleh mis der chosen schejn. Oj cores ojojoj cores. Cores vaksen den meter cores immer hecher. Es kimt a cat fin ach int veh. Ajeder shrat oj vej, oj vej.“ Its loose translation is: "Recently I was at a wedding. Ugly bride, beautiful groom. O misery, o misery, o misery, grows by the meter, higher and higher. Comes a time for lament. Everyone shouts oy vey, oy vey." So when he told he told this story, he also sang this song.

My mother, Margita Singer, neé Grünburg, was a very intelligent and clever woman. I'll tell you just enough for you to be able to imagine our circumstances. I got my first store-bought suit of clothes when I had my bar mitzvah [bar mitzvah - “son of the Commandments”, a Jewish boy that has reached the age of thirteen. A ceremony, during which the boy is declared to be bar mitzvah, from this point on he must fulfil all commandments of the Torah – Editor’s note]. I was 13 years old.

Otherwise it was all sewn from my father's old things. My father used to tell one joke about this: "Young Moritz comes to school with his nose up in the air, and the teacher says to him: Moritz, just because you have a new vest doesn't yet mean that you have to be proud. But they made the vest out of my father's pants, and I can't stand the smell!"

My mother was a very pretty and slim woman. She was one of eleven siblings. Two boys and nine girls. The girls got married to men from all over the monarchy, all the way down to Satmar [Satu Mare, a town in what is now Romania – Editor's note]. Back then I was still a little boy. Because they lived so far apart from each other, they didn't meet very much. I remember two of my mother's sisters.

The oldest was named Saly Horowitz. She married Rabbi Horowitz in Frankfurt am Main, who was also president of the Kolel Shomre Hachomos of Jerusalem [The Society of the Guardians of the Walls: a worldwide Jewish society that has for centuries financially and culturally supported the settlement of Jews in the city of Jerusalem – Editor's note]. He used to live in Jerusalem for three months of the year, and the rest in Frankfurt.

Another of the sisters married an assistant rabbi in Kezmarok. Her name was Roza Glück. I've already talked about my mother's brother, Nathan. He had a red moustache and beard. He was a very kind person. I can also talk about how as children we used to admire him, due to his skill in eating fish.

Back then people used to eat these small, white fish, that cost only a crown fifty a kilo [in 1929 it was decreed by law that one Czechoslovak crown (Kc), as a unit of Czechoslovak currency, was equal in value to 44.58 mg of gold – Editor's note]. They were very tasty, but were full of bones.

He knew how to eat them so that he'd stuff them in one side of his mouth, and bones would come out the other side. I don't remember my mother's other brother. He got married and settled down in the Hungarian town of Csenger. He made a living as a businessman. I unfortunately don't know anything about the fate of the rest of the siblings.

My father got married in 1914, about two years before I was born. He married the daughter of the Kezmarok rabbi. After the wedding he became a dayan [dayan: a judge of the rabbinical court – Editor's note] and taught German and religion at the German high school in Kezmarok. Kezmarok was mainly full of Germans, but they were from Spis, so they didn't speak grammatically correct German, but spoke a dialect. My father also spoke Yiddish, but it was so-called Oberländer Yiddish.

I was born into the worst poverty, in 1916, in Kezmarok. My parents named me Alexander, Jewish name Shmuel. With my father I spoke mostly German, but with my mother Slovak as well. I spent my early childhood in Kezmarok. Later, in 1926, we moved to Samorin, where my father became the head rabbi. For us it was a change to abundance.

It was a very good and big change from the standpoint of accommodations and supporting the family. Compared to Kezmarok, Samorin was a village, as Kezmarok was a town of artisans, but from the standpoint of supporting the family, it was incomparable.

A rabbinical position came up in Samorin, because the rabbi there was a former classmate of my father's, Dr. Weiss. He was a modern person, and became a rabbi in Wiener Neustadt [New Vienna]. For one, he himself recommended my father for his old position, and Akiba Schreiber also recommended him for it. Samorin was only a small town, about sixty Jewish families, which was about 200 souls.

But the problem was that there was only a Hungarian Jewish school there, and in Kezmarok I'd been attending a Slovak school, and my other siblings a German one. So we began learning Hungarian.

In Samorin we lived at 4 Hlavna St. The apartment had three rooms and a kitchen, no great luxury. The building also had a small garden, but there wasn't anything there, just a couple of flowers. As the oldest, I used to sleep in the last room, which also served as the living room. The windows faced the street.

The entire street was lined with acacia trees which gave off a beautiful aroma. Electricity had already been installed, but not running water. There was no sewage system either. The town had open sewers that collected dirty water, and the main sewer was in Hlavna Street. In the summer it stank horribly. I'll never forget how in the evening the beautiful aroma of the acacia flowers mingled with the stench of the sewers. It was intolerable. People had to close their windows.

My father loved books. In the room where I slept there was a huge cabinet full of books. Besides the cabinet there were also wooden shelves, which were full of books all the way up to the wood-paneled ceiling. These were books that my father had inherited from his grandfather, the Lucenec rabbi.

That means that they were very, very old. In 1942 I was in Budapest, and by then my parents were dirt poor. In Budapest I got to know one big businessman, Schlessinger. In those days Josef Schlessinger was a famous book merchant. Before the Anschluss, he had a big bookstore in Vienna and one in Budapest. Josef Schlessinger & Sohn.

He was a great expert on books, so I wanted my father to sell some of them. He was interested, so in 1942 he traveled to Samorin and picked out various books. For one book, my father would have gotten 8,000 pengö. Back then, one modest lunch in a "buffet" in Budapest cost about 40 fillér [100 fillér = 1 pengó].

You can imagine how much money that was, because already at that time there was great poverty. There wasn't anything to live on. But my father wouldn't sell that book for anything. Not for anything, because it was too valuable for him.

He didn't want to sell any of the books, even when he needed money badly. The books were worth millions, because they were also valuable from a historical standpoint. After the war, when I returned, I went to the ghetto in Zlate Klasy, where my parents had been staying before they deported them to Dunajska Streda.

The residents that had pilfered the books after the Jews were deported from the ghetto were using them as fuel for their stoves! Some were also in the bathroom. They were using them because they didn't have toilet paper. That was the fate of my father's library.

Disagreements amongst the Jewish population were resolved by the rabbi, thus my father. He was roch beyt din [from Hebrew, "head judge" – Editor's note]. Yes, he was a judge. He mainly judged disagreements of a business nature.

I personally never participated in any trial. I wasn't allowed to be present. It was top secret. He didn't even talk to my mother about these matters, just superficially. My father got along very well with the other members of the community.

My father didn't slaughter poultry, we had a shachter [ritual butcher] for that. He was named Stern, and lived beside the synagogue. He had a lot of children. He also butchered cattle. The only thing my father had to see was the veshet [throat]. The community also had a shammash [servant], who was named Schwarz. He lived in a house right by the synagogue. He took care of order and cleanliness in the synagogue, prayer rooms, ritual bath and the Jewish school.

- Growing up

I was born in 1916 in Kezmarok, the firstborn son of Jakub and Margite Singer. I grew up in a rabbinical family. At the age of three, I already began learning. Still back in Kezmarok I began attending cheder [cheder: religious primary school for the teaching of the Torah and Judaism – Editor's note].

I used to go see this one old person who taught me to read, write and pray. Well, and then we studied Hummash, that's the Five Books of Moses, complete with commentaries. As far as secular educations goes, I attended four grades of people's school in Kezmarok in the Slovak language, and then one more year in Samorin, Grade 5 of peoples' school, in Hungarian 6.

Then I began attending Talmudic school in Bratislava. It was named Yesodei HaTorah [foundations of the Torah – Editor's note]. That was for four years. At 3:00 p.m. we'd also go to the council school in Zochova Street. That was a normal council school, a Jewish one. There we studied secular subjects up until 6:00 p.m. I failed the first year of council school, not however because I was dumb.

In May my mother went to Bratislava to find out how her son was doing in school. Well, and Mr. Professor König told her: "I haven't seen your son for three months now!" I didn't have any money. In Bratislava there were two tennis players, one was a Jew, Mr. Danzig, the other a non-Jew, named Bula.

Bula was some sort of official at the Tatra Bank. Danzig was a sack wholesaler. The two of them used to play together. Well, and in the afternoon, during the time I was supposed to be in school, I went to Petrzalka to be a ballboy. I'd get fed there. Yes, there was a lot of hunger.

I was eleven when I arrived in Bratislava. I finished Grade 5 of people's school in Samorín, and then started here, in Bratislava. On Zitny Ostrov [Zitny Ostrov (Island) takes up the majority of the Lower Danube Plain, and is the largest inland island in Europe. The town of Dunajska Streda lies in the middle of Zitny Ostrov – Editor's note], all the Jewish elementary schools were Hungarian. That was five grades with one teacher in one classroom. To this day I can't imagine how that teacher did it, but we learned normally.

During my high school studies I lived in a sublet in Bratislava. Each day I'd go eat with a different family. We used to call it Tagessing [from the German Tag – day and essen – eat – Editor's note]. I used to go to former classmates, friends, of my father's. Each day to a different family. I wasn't picky, and I liked it everywhere the same.

In Bratislava I finished Talmudic Yesodei HaTorah and council school at the same time. From 1933 I studied at a rabbinical, Talmudic school in Nitra. There I studied for three years. Then I also studied at rabbinical school in Bratislava with Akiva Schreiber. After I finished I privately prepared for an entrance exam for 7th year of high school, on the basis of permission given by the Ministry of Education and National Enlightenment.

In 1933 I began studying at the yeshivah in Nitra. In Nitra I rented a room along with a classmate. We lived in Farska Street. It was close to school. It was a nice room that we had. For that my father always had to have money.

Accommodations cost 150 crowns a month. That was a lot of money for our family, which is why my parents weren't able to support me [in order for the reader to be better able imagine the amount spent on accommodations, I append the following: In the Regional State Archive in Sali, I found a document in which the Regional Office in Bratislava discloses the annual salary of the head rabbi of Samorín, Jakob Singer, to be 2,113.70 Czechoslovak crowns – Editor's note].

As far as food went, that was very miserable. I used to eat in the mensa [school cafeteria] of the rabbinical school. Luckily in Nitra there were Bulgarians selling vegetables 7, and those vegetables made up the main part of my daily menu.

For 50 hellers I got all sorts of vegetables. Bread was the most expensive, as a kilo cost a crown fifty. With one portion of vegetables, I always had a third or quarter of a loaf of bread. That's what I ate in the morning and evening, as the mensa only served lunch. On Saturday I always ate with some family.

The Rosh Ha Yeshivah [rosh ha yeshivah: "head of the yeshivah", thus the principal. Yeshivah; a school of higher Jewish religious education – Editor's note] was Rabbi Weissmandel 8, that means that he was in charge of everything, acceptance for studies, food, everything.

As far as teaching goes, that was taken care of by the main rabbi, Shmuel David Ungar. He lectured almost every day from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. The lectures were on individual sections of the Talmud. We took mainly the practical part, like the observance of various laws and regulations.

As a matter of fact, we acquired good basic knowledge of some important parts of the Talmud at the Jesodeh Hatorah school in Bratislava, but here at the yeshivah the studies comprised of, among others, very important commentaries made over the centuries by some Talmudic scholars,and alse extended to the deeper study of some parts of the Talmud that had not been included in the studies at the Jesode Hatorah.

There were also those among us that had rich parents who were particular about their son studying at such and such a school and with such and such a rabbi. In yeshivah they only went into special things. Mainly legal matters and historical background from the Talmud were interesting.

Rabbi Shmuel David Ungar was from Piestany. He had three sons. The oldest one was a rabbi in the town of Hlohovec. Our entire yeshivah attended his inauguration. His younger son was named Shalom Moshe Ungar, in Jewish jargon Sholem Moishe. We were studying at yeshivah together.

I was his older classmate. He married my cousin, the daughter of the Kezmarok rabbi Nathan Grünberg. During the war Rabbi Shmuel Ungar and his son Moshe became partisans. Rabbi Shmuel Ungar perished in 1944. He was buried in the forest.

After the war they exhumed him and transferred him to a cemetery in Piestany, where he was from. Moishe moved to the USA, where he became a rabbi. In the USA, he and Rabbi Weissmandel together restarted the functioning of the Nitra yeshivah. Sholem Moishe Ungar died a few years ago.

My uncle, the Kezmarok rabbi Nathan Grünburg, also had a son. His name was Meir Grünburg. He became a rabbi in Liptovsky Mikulas before the war. He and his wife and little boy survived the war as partisans.

After the war he and his wife returned to Kezmarok, where I went to visit them. I remember that when their son misbehaved, they'd threaten him that he'd get skin for lunch. Because during their partisan activities they often had nothing to eat, and so the partisans would make a broth from beef skin. Meir then emigrated and became the rabbi of some community in New York.

Now back to my studies at the yeshivah in Nitra. During lectures we'd mostly read Hebrew, or Aramaic text, but the commentaries were in Yiddish, but not that proper Yiddish, just mangled German, because proper Yiddsh is only spoken in countries like Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania. Here they spoke in so-called Oberländer Yiddish. Western countries used Oberländer Yiddish, and those were Unterländer Yiddish.

As a joke, the people that were from there were called Finns. Because when you asked him: "Where are you from?" He didn't reply: "Von Budapest, or von München, but in Jewish fin Munkács!" Instead of von they used fin.

I had classmates from various corners of the former monarchy, and some even also came from Belgium, France and the USA. I remember that the one from America was named Harris. Their parents had lived abroad for long years, but were from this region and had the money to send their children here.

A lot of the boys were also from poor families who had no other option but to send them here, so that here they'd get at least a bit of bread, because they didn't let anyone go completely hungry. In Nitra I didn't perceive any persecution, absolutely nothing. In the end, three hundred students were coming into the town, who needed to eat, clothing, and rented accommodations. Basically it also supported the local tradesmen and businessmen too.

From the Nitra yeshivah I went to Bratislava; I graduated to a "higher level". My father considered it to be a higher level, because Akiba Schreiber lectured in Bratislava, from the famous rabbinical Sofer family.

From a Talmudic standpoint, they were bigger experts than the rabbi in Nitra. The Nitra ones were more Hasidic 9, and dealt mainly with customs and morals. Well, and in Bratislava, from a Talmudic standpoint, it was of higher quality.

They came to Ungar not only for learning, but also because he was a Hasidic rabbi, a rebbe. Hasidim are very spiritual and enthusiastic believers, and followers of their miraculous rabbis. During prayers they dance and sing loudly, and dress like devout Jews in the East. Some wear black iridescent caftans, leather beaver hats, and black shoes dress shoes with white socks.

Attending the cinema while you were in the Yesodei HaTorah schol was forbidden. But sometimes I cheated and went to a movie for children. I remember how I once snuck into the Adlon Cinema. The Adlon Cinema was near the U milosrdnych hospital [Sisters of Mercy Hospital], where the Royko Passage is.

The Adlon Cinema belonged to one Jew whose son was going to school with me. He told me how to get in without paying. When the gates opened, you had to hide there, and when the usher wasn't paying complete attention and it got dark, you'd sit in a free spot. The first time I did it, it was a film with Richard Tauber, The Land of Smiles.

As a student, I had to work part-time on top of attending school. In Bratislava there was this one very rich barber. He had two shops. One of them was across from Stefanka [Café Stefanka] on the Palisades. It was an amazing barber shop for the rich, both men and women. The owner was a German, Neugebauer.

The owner of the Astoria Café, Mr. Löwy, who was from Kezmarok, recommended me to him. The Neugebauers had two children, a boy and a girl. The children's mother tongue was German, but even their parents already spoke in the Schwäbisch dialect. They had terrible problems at school, because they didn't know grammar.

I used to teach them. I was teaching German children how to speak and write German. They weren't stupid. The parents were very decent people, from a racial standpoint... I used to go there for the best haircuts, and ate chocolate, because they knew that I didn't eat that stuff from swine [pork meat isn't kosher, see also 4].

Their son, that small, weak, thin little boy – I didn't find this out until after the war, because I searched the family out – well, their son was the biggest bastard in the Hitlerjugend 10, and after the war had to escape from Bratislava. Then a few years after the war, his parents moved to Austria.

In my youth I was a member of Mizrachi 11 in Bratislava. The youth group was named Bené Akibah, Akiba's Sons. Its name was based on the following historical event: During the Roman occupation of the Jewish state they were the students of the largest Talmudic school, most of which died in some epidemic.

To this day, the Com Akibah fast is held in their honor. The members were mostly Orthodox Jews. It was basically the same as Hashomer Hatzair 12. The only difference was that the shomers were leftists. The program of both was emigration to the Palestine, to participate in hachsharah 13, prepare oneself for a certain profession and subsequently for the aliyah [aliyah: moving to the land of Israel – Editor's note].

The only difference was that they were leftists, and Mizrachi was religiously oriented. The celebrated rabbi of Mukachevo, Shapira 15, for example, was an anti-Zionist 14. He was constantly making speeches and battling with Zionism.

In Mukachevo things began to come to a head when they founded the first Hebrew high school there. Shapira, on the other hand, had a famous yeshivah in town. I'll tell you one anecdote from Mukachevo. People there were poor. National elections were being held, and a large part of the population there was Jewish. There was a lot of poverty, which is why they were supporters of the Communist Party.

That was all over the East. Well, and the state purposely set the elections in the town on the Simchat Torah holiday [Simchat Torah: the main significance of the holiday lies in the continuation of the Five Books of Moses.

The cycle of reading from the Torah ends and begins on the same day, and the public celebration connected with this expresses the joy inspired by this process – Editor’s note], so that Jews wouldn't come and vote. The religious ones really didn't go, either.

Everywhere in the town hung large posters saying: „JIDALECH HOBT KEJN MOJRE, HAINT IZ SIMCHET TOIRE, ŠTIMT OF DI NIMER FINEF ALLE ANDERE ZENEN A TINEC.“ Which means: "Jews, don't be afraid that today is Simchat Torah, vote for number five, all the others are shit." Because No. 5 were the Communists. They purposely set the elections during Simchat Torah, so that they wouldn't go vote and the Communists would get less votes.

I finished yeshivah in Bratislava without graduating, I didn't need it, because I transferred to secular studies. I didn't have a penchant for being a rabbi. My father took it very hard, because I was the oldest son. In time he calmed down, because I had brothers who were better suited for this position.

Mainly Jisrael. The others were still little. Jisrael started in our father's yeshivah. But at the age of 17 they took him away to the munkatábor [munkatábor, from Hunarian, a work camp – Editor's note].

After I left the yeshivah, I gradually began breaking away from Orthodox Judaism. Above all, I was no longer concerning myself with Talmudic studies, and didn't wear payes. I still ate kosher, it wasn't until in Hungary, in 1939, that for the first time I didn't eat kosher food.

It was complicated for me to transfer from the yeshivah to high school, because I was missing a basic secular education. My main problems were with mathematics. On the other hand, my favorite subjects were languages and history, especially the Middle Ages.

Today I can communicate in eight languages. Already from home I can speak German, Hungarian, Yiddish and Slovak. With my father and at school I studied Hebrew and Aramaic texts. During my high school studies, I began learning French.

After the war it gradually became a useless language. In order to find some sort of a job, I had to quickly learn English. In time I also added the Romanian language, which I learned during my five-year stay in that country. I also spoke Spanish well, but that faded away. I still more or less manage in it passively. Besides that I also know Czech, both spoken and written.

As far as religion goes, our family was strictly Orthodox 2. Already from the time I was little I had to wear a bottom tallit. The fringes were inside, not outside. I also wore payes, but only little ones.

I always had my head covered, only when playing soccer did I take the liberty of taking off my cap. My father was very much against it, but I was an excellent player. I even founded a local soccer team, SIT, Somorjai izraelita tornaegyesület [Samorin Israelite Physical Fitness Club].

We played together with Christian kids. On the whole, we got along well with the rest of the population. My father also had a good relationship with the Protestant and Catholic priests. Occasionally they'd meet lead discussions where they'd explain various Bible stories. They met mainly on walks in the countryside, or at schools.

During the holidays my father regularly put on feasts to which the entire community would be invited. My mother always baked cakes. She knew how to bake about a hundred different things. There was little alcohol.

The entire community used to come over to our place. Rich and poor. They'd set the table in that room that I used to sleep in, as it was the biggest. It was organized so that sixty people would fit inside. Women were separate, somewhere up front with my mother.

The community would meet like this for holidays like Purim [Purim: the holiday of joy. As is written in the Book of Ester, the holiday was decreed by Mordechai in memory of how God’s foresight saved the Jews of the Persian Empire from complete annihilation – Editor’s note], Simchat Torah and Chanukkah [Chanukkah: the Festival of Lights, which also commemorates the Macabbees’ uprising and the re-consecration of the Temple in Jerusalem – Editor’s note].

We observed holidays precisely according to regulations. The food was always the same, just during Passover [Passover: commemorates the departure of the Israelites from Egyptian captivity and is characterized by many regulations and customs.

The foremost is the prohibition of consuming anything containing yeast – Editor’s note] breadstuffs couldn't be served. My mother was very good at preparing it. For the bigger holidays my mother would buy a pike. Pike were very expensive back then, they cost three crowns fifty a kilo.

Otherwise during the year we had only whitings, in Hungarian "feher hal". They caught them right in Samorin. Yes, whitings, because carp cost two crowns fifty, and pike three crowns fifty. My mother would remove the skin, which would stay whole.

She'd gut and de-bone it. She'd make fish balls out of the meat and stuff the skin with the mixture. She'd cook it in an onion sauce, and served the fish with carrots on the side. She'd arrange it nicely on the dish. I loved it, even after the war.

While she was cooking she'd also add the fish head, which caused the sauce to thicken. She used to put it in to thicken it. The head made it as if it was in gelatin, because gelatin wasn't kosher. Around it she'd arrange beautiful little carrots.

She'd strain the gravy, take out the vegetables, and pour it over the fish. A fish prepared like this was only served when there was money, that's the only time we'd buy a pike. Otherwise we had whiting. That was also served with sauce, but it wasn't as good.

It was served on Friday evening and Saturday morning. My mother also used to make one other specialty. Goose breasts were ground up and stuffed into the goose's neck, and then baked. My mother even used to send that to me to the munkatábor, when the opportunity allowed.

The Sabbath differed from other days in that the entire house had to be clean. The entire apartment had to be properly cleaned. Clean laundry and a tidy table of course. Things were clean during the week too, my mother made sure of that, but especially on the Sabbath.

On Friday evening after having come home from the synagogue, candles appeared on the table. My mother would light them. Always only two. The candlesticks were made of silver. My father would bless the wine, and we'd sing the appropriate songs that are meant for Saturday.

For other holidays there were other ones. On Saturday I used to go for walks. We didn't play soccer. Every Saturday morning at the synagogue, between prayers or "Schachrit" and "Musaf", my father gave sermons related to the appropriate sidra [Sidra; literally "organization, section".

Decreed portion of the Testament that is read from the Torah for the Sabbath – Editor's note], which is different each week. The sermons were in German, and later also in Hungarian. He mixed in Yiddish and Hebrew expressions. The sermons couldn't be in Hebrew because most of the community wouldn't have understood them.

Over the years, they filled entire notebooks. These were then bound in hard covers. I got one that survived the war, at the Protestant priest's, and was sent to Jerusalem.

During childhood I liked Chanukkah the best. For one because of the story that the Jews defeated the enemy and re-consecrated the temple. And then because of fun. We used to make a "trenderli" [Denderli, trenderli: in Yiddish 'dreidl'.

Four-sided top. During Chanukkah children play with it for money that has been given to them during the holiday. Money was often substituted by other commodities, such as for example fruit or candy – Editor's note].

We'd find larger, dry branches, and carve it from those. We'd write Hebrew letters on the four sides, each one of which had some sort of meaning. Then the trenderli was spun, and the letter that came up would indicate the winnings.

There was gimel (ג), which stood for the Yiddish word ganz, meaning player takes all. Hei (ה), in Yiddsh halb, meaning half. Nun (נ), stood for non, nothing, and Yod (י), I don't even know anymore what that one was.

Most of the time we'd play for St. John's bread. St. John's bread is the sap of a tree. After drying it makes these hard, brown beans, which are then picked. Mainly we children ate it, because it was sweet. At Purim it was even ground for cakes. We played mainly for these beans and some five heller pieces.

When I reached the age of 13, I had a bar mitzvah. My father prepared me. At that time I got my first store-bought suit, which we bought at Engel's in Samorin. In the synagogue I had about a 15 – 20 minute speech.

It was an interpretation of the Torah. The celebration took place at our home. My mother baked, and the entire community was invited. There I had to give a speech. The speech related to the pertinent passage from the Torah for the given week.

I remember that I talked about the demolition of the Jerusalem Temple. This is because I was born in the month of Av, in which the anniversary of this national catastrophe takes place.

My father paid great heed to charity. For the Purim holiday, the custom is to send mishloach manot ["sending of gifts" at Purim – Editor's note]. It's written in the Megila Ester [Book of Ester (9:19), (9;22) – Editor's note], that's how they celebrated it in Persia, by sending each other gifts – mishloach manot, on the 13th of Adar.

In Samorin there were about better-off Jewish families. Among them were the families of a lawyer, a construction materials merchant, and a grain merchant. Ten to twelve, no more than that. They'd always send my father some money in an envelope.

Well, and my father would divide that money up, because there were about ten families that were dependent on that. They were very poor, and had children. Mostly they were various carters, or a tailor who wasn't doing well, or a cobbler.

This money was always divided up. My father would put it into envelopes, and I'd take them to the families. That was every year, because I was always home for the holidays.

During the summer months poor people in Subcarpathian Ruthenia 16 used to go on "yarche". They didn't call it begging, but yarche. They were so-called schnorrers [Schnorrer: a beggar, the Yiddish term schnoder means "to contribute" – Editor's note]. Mostly young people.

They used to walk around. They'd only stop there where they knew Jews lived. Older people were embarrassed, the younger ones simply came and asked if we didn't have money and something to eat. The older ones that used to come were from Poland too, and once we even had someone from Romania.

They always had a letter of reference from the rabbi of the town they were from that they had to arrange their daughter's wedding, that they'd lost their job, or had someone ill who needed an operation So that was charity.

Practically the first place they went after they got off the train was to the rabbi. He'd tell them that begging was forbidden in the town. My father had one community member who he'd charged with collecting money for the schnorrers.

His name was Mr. Schonfeld. He was an older man. He'd go from one family to another and collect money. In the meantime they'd sit at our place and got fed. Every day my mother would buy, and I'd carry home, as long as I was at home, eight liters of milk.

Twice each week, we baked three huge loaves of bread at Lichtenstein the baker's. I used to take them to the baker's on a wheelbarrow in this basket. That's all we had at home, which means that she couldn't feed them that much.

They got a huge piece of bread and white coffee. The white coffee wasn't even normal coffee, just a some roasted rye and milk. Two spoons of real ground coffee would be added to a liter of milk.

We prayed only at home and at the synagogue. It never happened that we'd pray on the train, for example. Once, when I was still a little boy, we went to visit someone in Spisske Podhradie. The way used to be through Magura [Spisska Magura is a spread-out sedimentary mountain range of the Outer Western Carpathian Mountains.

Spisska Magura used to be a lumbering and sheepherding region – Editor's note]. You used to go through a forest. Each coachman had a weapon hidden under his seat, because robberies still took place there. We set out on the trip early in the morning. On the way we stopped. My father got off the coach, went off to the side, put on his tefillin [tefillin: prayer straps – Editor's note] and prayed.

- During the war

I had five siblings. I can't tell you much about my siblings. I was older than they were. When they were little, I was studying away from home. I returned only for the High Holidays. I didn't spend much time with them.

The eldest of my sisters, Edita, was born in 1917. Her story is a downright tragedy. In 1939, during the Slovak State 17, she married Mr. Fridrich from Humenne. Her husband was a handsome, tall man. Already at that time there were various difficulties, so I didn't even make it to the wedding, just my parents.

Samorin was also attached to Hungary 18, while Humenne remained in the Slovak State. Before that we hadn't had state citizenship, just nationality. I had a home certificate [Home certificate: a document certifying residential rights in a certain municipality – Editor's note] for the town of Lucenec.

But they shoved Edita's husband off past the Hugarian – Slovak border, because he didn't have Slovak papers. He ended up in "no-man's land". The Hungarians then sent him to Poland, where he was shot. My sister was pregnant at the time. So my parents decided that it was necessary to bring her back from Humenne.

In 1939 I left for Budapest, because I couldn't stay in Samorin. Some people were yelling at me: „Csehúny, miért nem jött haza szeptemberben?“ ["Czech, why didn't you come home in September?"

After the First Vienna Arbitration Samorin was granted to Hungary, and at that time Mr. Singer was on the territory of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia – Editor's note]. Suddenly my parents wrote for me to immediately return, because my sister Edita needed our help.

We organized an illegal crossing from Bratislava. I came for her to the border, where smugglers brought her over onto Hungarian territory by the village of Miloslavov. She didn't even go home, but got on a train heading for Komarno and Miskolc.

My sister could have been living there to this day, because no one knew her there. They didn't know where she was from, and neither did they recognize the kid. She returned in 1944, just when they were preparing the deportation of Jews from Hungary.

The Jews were told that they would have to move to Poland and work there. Having no one in Miskolc but her little girl, she decided to join her parents.

In April 1944 they were first taken from their home in Samorin to the ghetto in Zlate Klasy (Nagymagyar) and from there to the railway station in Dunajska Streda, to be in the end transported like cattle in wagons to Auschwitz. There she ended up with her child and parents in the gas chamber.

My brother Jisrael was born in 1919. As I've already mentioned, he studied at my father's yeshivah, then at the age of 17 he was summonned to a munkatábor [munkatábor, a Hungarian labor camp – Editor's note]. He ended up in Erdelyi, and there the poor guy lived in all sorts of munkatábors. When the Nyilasites 19 came to power, he was deported to Mathausen 20. He died of typhus, a few days before liberation.

My sister Jolana was the only one of my siblings to survive. Jolana was in Auschwitz, and then in other camps, but ended up in Bergen-Belsen 21. When I returned home, I met one girl from Mliecno that told me about her.

Two days before the liberation she was walking along in Bergen-Belsen, and some girl was lying there, under a tree. She heard her calling her name. She didn't even recognize her. It was my sister Jolana. She'd caught typhus there, and her hair had fallen out.

She caught all sorts of diseases, and was close to dying. The Swedish Red Cross picked them up. Back then that girl told me that she likely wouldn't live, because thousands there had died, mainly of typhus, and before that she'd had other diseases from Auschwitz. In the end she survived.

Jolana didn't even return home. For one there wasn't where [to return to], and then she married a fellow prisoner. He was from Hungary. His name was Laufer. They left for New York together.

In New York they ended up in the company of extremely Orthodox Jews, and they became ultra-Orthodox as well. Their son is a rabbi and at the same time a lawyer in New York. I've never gone to visit them, but we used to meet, they came to see me in Canada. Unfortunately I don't know if my sister is still alive, because already five years ago she had a stroke, and I didn't know absolutely anything about her.

I maintained contact with her through one nephew who was from Zeliezovce. They took care of her, which means that she had a nurse and all. I've got this impression that she must have died long ago,. but that they're keeping it a secret from me. I still write her during the holidays. She was the only one from our family who remained alive.

My brother Lazar wasn't very much into studying. He became a baker by trade. During the Holocaust he was also in Budapest for some time. In Budapest they caught him, because he hadn't gone to a munkatábor. I even met him in Budapest once.

He had some food, and brought me some bread too. While still in Budapest, he met some Frenchmen, who were deported along with him to Mauthausen. Well, and there in the camp they planned an escape attempt together, but they caught and publicly executed them. The youngest, Herman, went straight into the gas in Auschwitx together with my parents.

At the end of 1939 I signed up in Budapest for munkaszolgálat [22, 23] in Nagykaty. There was an army assembly point there. We got a yellow armband, but no uniform. I walked all over Erdely 24. We did all sorts of farm work.

I even took care of pigs for some counts. Finally in 1940 they sent me home, because by error they had me registered as having been born in 1915, and was born in 1916. I didn't go home, but straight to Budapest.

There I at first worked in a konzervgyár [cannery] on the outskirts of Csepel for 20 hellers an hour. I worked there along with one boy who I'd graduated with. We carted garbage in a wheelbarrow to the garbage dump. By the dump there was a fence, in which we made a hole and hid food there.

You weren't allowed to carry anything out, because when we left the factory, they'd check us. We lived off that. Things were rough there.

After two months, as soon as I got my bearings a bit, I left the factory and began teaching German and French. I taught both children and adults, from better-off Christian families in Budapest. Unfortunately, at this time almost all building supers were informers for the state police. Our super informed on me, that as a Jew I was illegally avoiding the labor camp, and on 15th December 1942 the police arrested me.

They led me off to a labor camp in the town of Esztergom. With shorter stops in camps in Erdelyi, I ended up in the town of Csikszereda. The camp was up on Hargita Hill. Csikszereda was the highest camp of them all. We walked 13 kilometers to work, and had to work for 8 hours.

While we were with the camp's army commanders, it was relatively normal, and we had food to eat. There weren't even any beatings, just once in a while someone got a slap or whacked with a cane. One day after assembly they assigned us to some camp where we were preparing defenses, bunkers against the Russians for the Hungarian army.

That was something awful. The first day, the commander picked me out for some reason, came over to me, there was something that he didn't like about me, and so as we were standing there in line, he hit me with a whip right across the eyes.

I couldn't see for a week. He was a second lieutenant, in civilian life a teacher, even. He wanted to introduce himself, which he also succeeded in doing. I don't remember his name anymore, but I searched for him for a long time. Maybe he died when the Russian army arrived.

We did the worst slave work there. We were supposed to dig lines of defense, bunkers, in the cliffs. Actually, they were trenches in the rock. Two of us had sledgehammers. The instructions were to dig down 60 centimeters into the rock within a certain time, and insert some dynamite.

We were already very weakened, and the hammers were heavy. When we didn't meet the quota, it was pants down and we got caned. You can't imagine that. Luckily it didn't last long, because the Russians were drawing near. You could already hear it in the distance.

One morning, around 4:00 a.m., gendarmes came, kakastollasok 25. We had to leave everything in that pajta [pajta is the Hungarian word for barn – Editor's note] where we were sleeping, and could only take our pants and personal things. I thought that was the end. Up on that hill they lined us up, completely naked, we had to give everything up. At that time I also lost my last documents and a picture of my mother.

They took everything, whoever had money, or a ring, papers, identification. I thought they were going to shoot us. Finally they loaded us up on a horse-drawn wagon and we rode to the station by the town of Csikszereda. There we stayed for some time as well.

At that station they loaded us into wagons. We didn't know where we were going. Finally, a week later we arrived in the Hungarian town of Rakospalota, a suburb of the capital Budapest. Daily we walked to Budapest and worked cleaning up the rubble left from the bombarded buildings.

Later on we were building anti-aircraft emplacements (FLAG- Fliegerabwehrgeschütte) [the interviewee is using a little-known variation on the expression "flak", a German acronym of Fliegerabwehrkanone, meaning `anti-aircraft guns' (more literally, `aircraft defense guns') which passed into common English usage – Translator's note].

In the neighborhood of Rakospalota for the Hungarian army under the command of the Germans The Germans had a radar station there. During a whole month we didn't shoot down even one plane. On the contrary, they bombed us constantly. Fragments of our own anti-aircraft shells were falling, and many people were wounded.

The fragments were so sharp, that when they fell down, it could even cut your head off. The shells were 70 cm long. There were about four in a case. During the day, mainly American and English bombers were flying over, and in the evening Russian planes, accompanied by the launch of so-called Stalin's lamps, which had the capacity to light up the target so intensely that at night one could read a newspaper on the ground.

They were dropping massive amounts of 50 kilo bombs. For us it was dangerous mainly after the attack, when you came out of the trenches, because there were fragments of our own shell falling. When it hit someone, they took them to the hospital.

- After the war

In October 1944 the Horthy regime 26 fell, and they Nyilasites, led by Szálási 27 assumed power in Hungary. Finally they deported us via Hegyeshalom to Mauthausen, where on May 5th the Allies liberated us.As I've already mentioned, my father had a brother named David Singer.

David also had a Talmudic education. He owned a small bookstore in Bratislava, in Kapucinska Street, with Hebrew, mainly religious books and textbooks. Across the street from him was a huge bookstore, Lichtenfeld. The owner had once upon a time studied at yeshivah with Uncle David.

One could say that he also helped my uncle, he'd give him books on credit, which he could then sell. David had a good wife. She was from Budapest. Her name was Sara Unger. They had two children, boys. The older was named Abraham, the younger Israel.

They were very wise and talented boys. At the beginning of 1942 David's wife's brother searched me out in Budapest, asking me to help him smuggle those children into Hungary. Sara knew that I'd already helped smuggle my sister across, which is why Unger came to see me.

The parents remained in Bratislava. I smuggled them across at the same place as my sister Edita. We got on a train near the border village of Uzor and I went with them to Komarno and from there to Budapest. There I handed them over to their family.

Well, and I met the older one, Abraham, when in August 1944 they were transporting us back to Budapest from Csikszered. We stopped somewhere at some station, and got off the train. Suddenly someone said my name. Some big boy, and it was Abraham.

He'd grown unbelievably in two years. He recognized me, I didn't him. They'd also come from the Ukraine [Subcarpathian Ruthenia – Editor's note]. After the war, someone told me that that boy had survived in Budapest. So I went to Budapest from Mauthausen with the army, first with the English and then with the Russians, in the hope that I'd meet him there.

Unfortunately, just like his whole family, he didn't survive the war. I was in Budapest for only a short time. In August I returned to Samorin. Only a few Jewish boys and girls returned to Samorin. I had no place to go in Samorin, because the building we'd lived in was occupied, Nagy Sándor's family was living there.

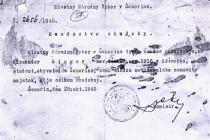

They were decent people, they freed up that large room for me right away. There was just one old ottoman there, and one closet. Nothing else. At that time, the Samorin municipal office gave me a document that said that I was completely broke.

I then set out to find work in Bratislava, but somehow I wasn't having any luck, so I left for Prague. Shortly thereafter I was working for a lawyer and at the Schenker shipping company. It didn't suit me, because there it was organized in the "American way". We worked in these cubicles and watching over us was a boss whose office was higher up. They only took me due to my language skills, because I didn't understand the transport business.

In 1947 I took out a classified ad in the papers: "Clerk with knowledge of French and German with a talent for business looking for employment." I of course didn't have any business experience. At most, that I'd worked for three months in one export company.

It was only a tiny little company, about four employees. The owner was one Mrs. Heydukova. She was a collaborator, because during the war she'd had some German staying with her. The salary I got was just enough to pay the rent. You couldn't live on it.

I used to go for three-crown lunches, but normally lunch would have cost seven crowns. I ate with one Prague family. The husband worked and the wife was at home, so she cooked. Then more people started coming to their place for lunches, who'd pay them for that. In 1947 I got a job in Jablonec. Back then there were still former German companies there, which had a national administrator. Well, and one of the administrators gave me a job.

In 1948 I was myself named the national administrator of three small companies that exported costume jewelry. They were small companies, which I had to merge. There were still German employees there too, who hadn't been deported 28. All together about 15 employees.

There I needed English. I began learning English during the years 1939 to 1942. I was staying with one friend in Budapest. He had these scratched-up records, with about 30 lessons. It was a very good system. There was a book with it as well. There I gained the basics of English.

From small companies under national administration, a large export firm was founded, Skloexport. The main customers were American. Skloexport was later renamed to Jablonex. It was in charge of exporting costume jewelry.

In 1953 I was named the best worker in the entire sector of the Ministry of Foreign Trade. The award was given by the ministry itself. I was mainly in charge of the American market and Canada. In 1954 I went on a business trip to five countries in southeast Asia, which lasted 5 months, and then in 1956 – 1958 I went on three business trips to Canada

During the years 1951 - 1954 the press issued daily anti-Jewish articles under the pretext of anti-Zionism. I myself didn't feel much of this campaign – I was doing my job to the satisfaction of the Party and my management. But suddenly, a few weeks after I returned home in 1958 from a two-month business trip from Canada, the newly appointed general manager asked me to quit my job without specifying the reasons.

I refused to do so, telling them to give me notice in accordance with the conditions of my contract. Highly placed party officials had a hankering for my position. They wanted to throw me out, and mainly to travel instead of me. The company had my passport, I had to hand it in each time.

Back then, based on a decision of the highest regional Party secretary in Liberec, it was decided that Skloexport would move from Prague to Liberec. They came with the fact that I wouldn't have to resign, but that I'd take a position in Liberec.

They offered me the post of manager of the export department. I was even supposed to get a salary increase of a thousand crowns. It was a trap. I got a new contract. I went happily home, well, and within the scope of a one-month layoff notice, they let me go from my new place of work a week before I was to start. I had of course had to resign from my old position.

That's what they did to me, an award-winning employee. I turned to one friend, a former colleague, who helped me find a job in Bratislava. Concretely, this is what happened: Back in 1948, the company hired one "working-class cadre".

You see, as soon as the Communists took power 30, the regional committee ordered Skloexport to employ one of their people in a management position. The aforementioned "working-class cadre" was a former farmer, the same as his wife.

But he'd been working somewhere for a baker, he still had "flour on his cap" when he came to introduce himself at the company. He didn't understand our work, which is why three of us were chosen to train him. I taught him languages. We even used to go to soccer together on Sundays, when weren't working.

He got very spoiled, the glory went to his head when he became the general manager of some company in Prague. There he was already a big man. Then when they threw me out of the company, he helped me a lot.

He was the only person who gave me a helping hand when I was out on the street without a job and a place to live. From January 1960, I began working in Bratislava. I worked there until I retired. For seven years I worked to increase my pension.

Besides this, at the start of the 1970s I taught foreign trade operations at the Economics University in Bratislava as an external worker. The rector there got the idea that they needed a person right from a foreign trade company, and our manager recommended me to him.

I was married, but I don't want to talk about my wife, as it ended badly. I've got a daughter, who I still keep in touch with. She worked in a large research institute. She's qualified as a sociologist, and documentarian.

During my stay in Jablonec, I was an active member of the Jewish religious community. I also participated actively in the community's religious life. I was even the only one who was capable of leading prayers. In the building that I lived in, there was also a prayer room.

I got an apartment there from the Jewish community. After moving to Bratislava, I became a member of the community here in Bratislava. I now only go to the synagogue only for the High Holidays, but I always go to the community.

I eat in our community's kosher dining room, because my state of health is such that my stomach is completely ruined as a result of the war. During the war for some time I even ate only raw corn and oats that had been left by horses. That made holes in my mucous membranes. After that I never had a good stomach or intestines.

I'd say that my relationship to Israel is very positive. I've been there three times. What impressed me the most was their courage and hard work, but mainly that that they've gotten used to life in constant danger. Their descendants have inherited that.

They've already got it as an inborn trait. When you ask them how they take it, that every while there's a pile of dead bodies... They take it normally, that it's a part of life. I've got to say, I wouldn't have the nerves for it. The revolution in 1989 31 didn't bring any changes to my life.

As a retiree, I'm still employed part-time. In my spare time I read, listen to the radio and watch television. I watch the news on various TV stations. For example the BBC seems to me to be quite anti-Jewish. When Palestinians blow up a school bus with Jews in it, they don't devote any space to this information. But when Jews invade a Palestinian refugee camp to catch the killers, right away the television and papers are full of it.

Glossary:

1 Sephardi Jewry: Jews of Spanish and Portuguese origin. Their ancestors settled down in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, South America, Italy and the Netherlands after they had been driven out from the Iberian peninsula at the end of the 15th century.

About 250,000 Jews left Spain and Portugal on this occasion. A distant group among Sephardi refugees were the Crypto-Jews (Marranos), who converted to Christianity under the pressure of the Inquisition but at the first occasion reassumed their Jewish identity. Sephardi preserved their community identity; they speak Ladino language in their communities up until today.

The Jewish nation is formed by two main groups: the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi group which differ in habits, liturgy their relation toward Kabala, pronunciation as well in their philosophy.

2 Orthodox communities: The traditionalist Jewish communities founded their own Orthodox organizations after the Universal Meeting in 1868-1869.They organized their life according to Judaist principles and opposed to assimilative aspirations. The community leaders were the rabbis. The statute of their communities was sanctioned by the king in 1871.

In the western part of Hungary the communities of the German and Slovakian immigrants’ descendants were formed according to the Western Orthodox principles. At the same time in the East, among the Jews of Galician origins the ‘eastern’ type of Orthodoxy was formed; there the Hassidism prevailed. In time the Western Orthodoxy also spread over to the eastern part of Hungary.

294 Orthodox mother-communities and 1,001 subsidiary communities were registered all over Hungary, mainly in Transylvania and in the north-eastern part of the country, in 1896. In 1930 30,4 % of Hungarian Jews belonged to 136 mother-communities and 300 subsidiary communities. This number increased to 535 Orthodox communities in 1944, including 242,059 believers (46 %).

3 Orthodox Jewish dress: Main characteristics of observant Jewish appearance and dresses: men wear a cap or hat while women wear a shawl (the latter is obligatory in case of married women only). The most peculiar skull-cap is called kippah (other name: yarmulkah) (kapedli in Yiddish), worn by men when they leave the house, reminding them of the presence of God and thus providing spiritual protection and safety.

Orthodox Jewish women had their hair shaved and wore a wig. In addition, Orthodox Jewish men wear a tallit (Hebrew term) (talles in Yiddish) [prayer shawl] and its accessories all day long under their clothes but not directly on their body. Wearing payes (Yiddish term) (payot in Hebrew) [long sideburns] is linked with the relevant prohibition in the Torah [shaving or trimming the beard as well as the hair around the head was forbidden].

The above habits originate from the Torah and the Shulchan Arukh. Other pieces of dresses, the kaftan [Russian, later Polish wear] among others, thought to be typical, are an imitation. According to non-Jews these characterize the Jews while they are not compulsory for the Jews.

4 Kashrut in eating habits: kashrut means ritual behavior. A term indicating the religious validity of some object or article according to Jewish law, mainly in the case of foodstuffs. Biblical law dictates which living creatures are allowed to be eaten. The use of blood is strictly forbidden. The method of slaughter is prescribed, the so-called shechitah.

The main rule of kashrut is the prohibition of eating dairy and meat products at the same time, even when they weren’t cooked together. The time interval between eating foods differs. On the territory of Slovakia six hours must pass between the eating of a meat and dairy product. In the opposite case, when a dairy product is eaten first and then a meat product, the time interval is different. In some Jewish communities it is sufficient to wash out one’s mouth with water. The longest time interval was three hours – for example in Orthodox communities in Southwestern Slovakia.

5 Chatam Sofer (1762-1839): Orthodox rabbi, born in Frankfurt, Germany, as Moshe Schreiber, who became widely known as the leading personality of traditionalism. He was a born talent and began to study at the age of three. From 1711 he continued studying with Rabbi Nathan Adler.

The other teacher, who had a great influence on him, was Pinchas Horowitz, chief rabbi of Frankfurt. Sofer matriculated in the Yeshivah of Mainz at the age of 13 and within a year he got the ’Meshuchrar’ – liberated – title. The Jewish community of Pozsony elected him as rabbi by drawing lots in 1807. His knowledge and personal magnetism soon convinced all his former opponents and doubters. As a result of his activity, Pozsony became a stimulating spiritual center of the Jewry.

6 People’s and Public schools in Czechoslovakia: In the 18th century the state intervened in the evolution of schools – in 1877 Empress Maria Theresa issued the Ratio Educationis decree, which reformed all levels of education.

After the passing of a law regarding six years of compulsory school attendance in 1868, people’s schools were fundamentally changed, and could now also be secular. During the First Czechoslovak Republic, the Small School Law of 1922 increased compulsory school attendance to eight years.

The lower grades of people’s schools were public schools (four years) and the higher grades were council schools. A council school was a general education school for youth between the ages of 10 and 15. Council schools were created in the last quarter of the 19th century as having 4 years, and were usually state-run.

Their curriculum was dominated by natural sciences with a practical orientation towards trade and business. During the First Czechoslovak Republic they became 3-year with a 1-year course. After 1945 their curriculum was merged with that of lower gymnasium. After 1948 they disappeared, because all schools were nationalized.

7 Bulgarian gardeners: Bulgarian gardeners have taken a prominent position in the cultivation of vegetables throughout Europe. Their migration began at the turn of 18-19. century. They started to arrive in Slovakia at the end of the 19th century.

8 Weissmandl, Chaim Michael Dov (1903 -1957): rabbi Weissmandl became famous for his tireless efforts to the save the Jews of Slovakia from extermination at Nazi hands during the Holocaust. During the period of WWII, Weissmandl was an unofficial leader of the Working Group of Bratislava.

In the final days of the war he was evacuated by a transport organized by Rudolf Kastner with German permission. Later he moved to the United States, where together with those students of the original Nitra Yeshiva who were fortunate enough to survive the Holocaust, he established the Yeshiva Farm Settlement at Mount Kisco, New York.

9 Hasidic Judaism: Haredi Jewish religious movement. Some refer to Hasidic Judaism as Hasidism. The movement originated in Eastern Europe (Belarus and Ukraine) in the 18th century. Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (1698–1760), also known as the Ba'al Shem Tov, founded Hasidic Judaism.

It originated in a time of persecution of the Jewish people, when European Jews had turned inward to Talmud study; many felt that most expressions of Jewish life had become too "academic", and that they no longer had any emphasis on spirituality or joy. The Ba'al Shem Tov set out to improve the situation. In its initial stages, Hasidism met with opposition from several contemporary leaders, most notably the Vilna Gaon, leader of the Lithuanian Jews, united as the misnagdim — literally meaning "those who stand opposite".

10 Hitlerjugend: The youth organization of the German Nazi Party (NSDAP). In 1936 all other German youth organizations were abolished and the Hitlerjugend was the only legal state youth organization. From 1939 all young Germans between 10 and 18 were obliged to join the Hitlerjugend, which organized after-school activities and political education.

Boys over 14 were also given pre-military training and girls over 14 were trained for motherhood and domestic duties. After reaching the age of 18, young people either joined the army or went to work.

11 Mizrachi: The word has two meanings: a) East. It designates the Jews who immigrate to Palestine from the Arab countries. Since the 1970s they make up more than half of the Israeli population. b) It is the movement of the Zionists, who firmly hold on to the Torah and the traditions.

The movement was founded in 1902 in Vilnius. The name comes from the abbreviation of the Hebrew term Merchoz Ruchoni (spiritual center). The Mizrachi wanted to build the future Jewish state by enforcing the old Jewish religious, cultural and legal regulations.

They recruited followers especially in Eastern Europe and the United States. In the year after its founding it had 200 organizations in Europe, and in 1908 it opened an office in Palestine, too. The first congress of the World Movement was held in 1904 in Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia), where they joined the Basel program of the Zionists, but they emphasized that the Jewish nation had to stand on the grounds of the Torah and the traditions.

The aim of the Mizrach-Mafdal movement is the same in our days, too. It supports schools, youth organizations in Israel and in other countries, so that the Jewish people can learn about their religion, and it takes part in the political life of Israel, promoting by this the traditional image of the Jewish state.

( HYPERLINK "http://www.mizrachi.org/aboutus/default.asp" http://www.mizrachi.org/aboutus/default.asp; HYPERLINK "http://www.cionista.hu/mizrachi.htm" www.cionista.hu/mizrachi.htm; Magyar Zsidó Lexikon, Budapest, 1929).

12 Hashomer Hatzair in Slovakia: the Hashomer Hatzair movement came into being in Slovakia after WWI. It was Jewish youths from Poland, who on their way to Palestine crossed through Slovakia and here helped to found a Zionist youth movement, that took upon itself to educate young people via scouting methods, and called itself Hashomer (guard).

It joined with the Kadima (forward) movement in Ruthenia. The combined movement was called Hashomer Kadima. Within the membership there were several ideologues that created a dogma that was binding for the rest of the members. The ideology was based on Borchov’s theory that the Jewish nation must also become a nation just like all the others.

That’s why the social pyramid of the Jewish nation had to be turned upside down. He claimed that the base must be formed by those doing manual labor, especially in agriculture – that is why young people should be raised for life in kibbutzim, in Palestine.

During its time of activity it organized six kibbutzim: Shaar Hagolan, Dfar Masaryk, Maanit, Haogen, Somrat and Lehavot Chaviva, whose members settled in Palestine. From 1928 the movement was called Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard). From 1938 Nazi influence dominated in Slovakia.

Zionist youth movements became homes for Jewish youth after their expulsion from high schools and universities. Hashomer Hatzair organized high school courses, re-schooling centers for youth, summer and winter camps. Hashomer Hatzair members were active in underground movements in labor camps, and when the Slovak National Uprising broke out, they joined the rebel army and partisan units.

After liberation the movement renewed its activities, created youth homes in which lived mainly children who returned from the camps without their parents, organized re-schooling centers and branches in towns. After the putsch in 1948 that ended the democratic regime, half of Slovak Jews left Slovakia. Among them were members of Hashomer Hatzair. In the year 1950 the movement ended its activity in Slovakia.

13 Hakhsharah: Training camps organized by the Zionists, in which Jewish youth in the Diaspora received intellectual and physical training, especially in agricultural work, in preparation for settling in Palestine.

14 Zionism: a movement defending and supporting the idea of a sovereign and independent Jewish state, and the return of the Jewish nation to the home of their ancestors, Eretz Israel – the Israeli homeland. The final impetus towards a modern return to Zion was given by the show trial of Alfred Dreyfus, who in 1894 was unjustly sentenced for espionage during a wave of anti-Jewish feeling that had gripped France.

The events prompted Dr. Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) to draft a plan of political Zionism in the tract ‘Der Judenstaat’ (‘The Jewish State’, 1896), which led to the holding of the first Zionist congress in Basel (1897) and the founding of the World Zionist Organization (WZO). The WZO accepted the Zionist emblem and flag (Magen David), hymn (Hatikvah) and an action program.

15 Shapira, Chaim Eleazar (1872-1937): Rabbi of Munkacs, Hungary (today Mukachevo, Ukraine) from 1913 and Hasidic rebbe. He had many admirers and many opponents, and exercised great influence over the rabbis of Hungary even after Munkacs became part of Czechoslovakia, following the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy after World War I.

An extreme opponent of the Zionist movement and the Orthodox Zionist party, the Mizrachi, as well as the Agudat Israel party, he regarded every organization engaged in the colonization of Erets Israel to be inspired by heresy and atheism.

He called for the maintenance of traditional education and opposed Hebrew schools that were established in eastern Czechoslovakia between the two world wars. He also condemned the Hebrew secondary school of his town. He occasionally became involved in local disputes with rival rebbes, waging a campaign of many years.

16 Subcarpathian Ruthenia: is found in the region where the Carpathian Mountains meet the Central Dnieper Lowlands. Its larger towns are Beregovo, Mukacevo and Hust. Up until the First World War the region belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, but in the year 1919, according to the St. Germain peace treaty, was made a part of Czechoslovakia.

Exact statistics regarding ethnic and linguistic composition of the population aren’t available. Between the two World Wars Ruthenia’s inhabitants included Hungarians, Ruthenians, Russians, Ukrainians, Czechs and Slovaks, plus numerous Jewish and Gypsy communities.

The first Viennese Arbitration (1938) gave Hungary that part of Ruthenia inhabited by Hungarians. The remainder of the region gained autonomy within Czechoslovakia, and was occupied by Hungarian troops. In 1944 the Soviet Army and local resistance units took power in Ruthenia.