Simon Grinshpoon

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: November 2002

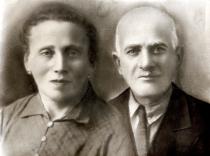

Simon Grinshpoon does not look old. He is still a very interesting man. He lives with his wife in a big three-bedroom apartment in the city center of Kiev. They have three pet dogs. Simon's story is interesting, and he presents it in a witty manner. I believe he enjoyed telling me about an amazing chapter of his life.

My family background

Growing up

Our religious life

My school years

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

I don't know the name of my great-grandfather on my father's side. When he was about 13 years old, he was sent to the tsarist army. He became a cantonist 1. He served in Siberia. All he knew about his family was that he was a Jew and came from Ukraine. When he was released from his service in the army he went to Ukraine on foot. It took him three years to get there, and he settled down in Berezovka, a big Ukrainian village in Vinnitsa province. It is located near the small Jewish town of Chernivtsi. There were about 20 Jewish families living in Berezovka. My great- grandfather married a young Jewish girl, and they had many children. I have no more details about their family. One of their children was Shloime Grinshpoon, my grandfather, who was born around 1845.

My grandfather Shloime didn't have any education. He was very strong and worked as a loader at the mill in Berezovka: he carried bags with flour and grain. Grandmother Bluma was about five years younger than him. Shloime and Bluma had six children. Two of them died in infancy. The remaining four were Perl, born in 1870, Gedali, born in 1875, Liber, born in 1880, and my father Gersh, born in 1888.

They were a religious family. They followed the kashrut and celebrated Sabbath and all Jewish holidays. There was no synagogue in the village, and on big holidays like Pesach, Chanukkah and Rosh Hashanah the family went to Chernivtsi and stayed with their acquaintances. They took food (chicken, honey, bread) with them to last for the duration of their stay, because they were a big family. The adults went to the synagogue in Chernivtsi, and the children stayed at home. The older children looked after the younger ones. There was no cheder in the village either, and all children got primary education at home. Their teachers - I believe they were teachers from the cheder in Chernivtsi - taught them religion and how to read and write. Their family was wealthy, although not rich. But they had everything they needed.

My father's older sister Perl married an employee of the sugar factory, which was located in the village of Borovka. His last name was Danilovich. They had two children: a son called Naum and a daughter called Ida. Perl died after Ida was born, and her husband died before Ida turned 12. If children became orphaned, an older boy could only get married after his sister did, according to Jewish law. The boy became head of the family and had to make all necessary arrangements for his sister before he could get married. Ida married a Jewish man called Frechtman. They moved to Moscow, and he worked as chief mechanic at a plant there. Naum didn't get married. He worked in the sugar factory in Borovka like his father and later in other factories in Vinnitsa region.

Shloime's sons - Gedali, Liber and my father - helped their father at the mill from their childhood on. Gedali purchased that mill in due time and became its owner. He moved to Chernivtsi. Milling was a profitable business, and Gedali, his wife, their daughters Perl and Haika and their son Avrum were wealthy. The family was religious. They observed all traditions and celebrated holidays. In the 1930s the Soviet authorities expropriated Gedali's mill in the course of the dispossession of the kulaks 2. Avrum and his sisters' husbands were under suspicion by the Soviet authorities as former proprietors because they owned stores. They left their property and moved to the town of Mogilyov-Podolskiy where they became workers. Gedali's wife died. Gedali couldn't make his own living, and my father and Liber always supported him. Gedali died in the early 1930s.

Liber was a dealer before the revolution. He purchased grain from the local landlords and sold it taking his cut. After the revolution he moved to Yaruga, Vinnitsa region, with his family and became a farmer. Liber and his wife Sima had six children: their firstborn son Shloime, their daughters Sarah and Perl, another son called Moshe and their youngest, the twins Rachmil and Inna. Sima died in the early 1930s and Liber died in 1935. I don't know exactly what Sima died of, but I believe she may have starved to death. Shloime became a professional military. He served in Moscow. Perl married Fleider, the chief of the militia school in Odessa. Moshe lived with us until he was recruited to the army. Liber's daughter Sarah and her husband worked at primary school in the village of Satkovtsy near Yaruga. They taught writing, reading and . They raised the twins, Rachmil and Inna. During the war Shloime and Moshe were in the army. Sarah, her husband, Rachmil and Inna were in evacuation in Uzbekistan and Perl was in Sverdlovsk where her husband was chief of the district militia department. After the war all of them returned to Mogilyov-Podolskiy. That's all I know about them.

My father received education at home. From the age of 9 his brothers and he helped grandfather at the mill: He learned to sort, load and pack grain. In the course of time he learned how to do business, was in the flour trade and earned good money. He was working at the mill when, in 1909, he was introduced to my mother.

My mother, Leiba Grinshpoon [nee Goldenberg] came from the town of Yaruga. Her father Mordukhai and her mother Anya were born in the 1830s.

There were about 300 Jewish families in Yaruga. Ukrainian farmers lived in a small village near Yaruga. The people of Yaruga grew wine. Some of the Jews were craftsmen and merchants. There were tailors, shoemakers, glasscutters, carpenters, plumbers and barbers among them. Wine-growers were considered to be of a higher class than the rest of society in Yaruga. It was common opinion that they were the wealthiest and most honest people, while tailors or shoemakers, for example, could take advantage of their customers. Parents didn't allow their children to marry someone from a craftsman's family. My mother, when speaking about such cases, would even comment angrily, 'He [someone] should rather have married a Russian girl'.

There were four synagogues in Yaruga. Depending on their profession, the town people went to different synagogues. The biggest one was for richer people. It wasn't just a synagogue - this was a bes medresh, as we called it in Yiddish. There was a small synagogue called shneyders shilekhl - a little synagogue for tailors. Workers and laborers had their own synagogue, too, and there was also a prayer house for everybody. There were a rabbi, a chazzan and two shochetim in Yaruga. They all attended the main synagogue, the bes medresh. There was also a Christian church in Yaruga. On Sundays there was a big market in the central square, where farmers from the surrounding villages were selling their products.

My grandfather on my mother's side, Mordukhai Goldenberg, was estate manager for a landlord called Vinogradsky. Vinogradsky had a big estate in Yaruga. He relied on my grandfather's expertise very much. My grandfather's advice on all matters of everyday life was much valued by many people. Ukrainians called him 'Mordukhai, the Smart'. After my grandfather died his son Isaac replaced him at this position.

My mother was the 13th child in the family. She was born in 1886 when my grandmother was already 51 years old. She couldn't breastfeed her, and so my mother was fed by her older sister Hana, who was the fourth child in the family. Hana, her husband Bencion and their children lived in the town of Tomashpol, 60 km from Yaruga. Bencion was a merchant of Guild I 3. Bencion and Hana had eight children. Hana had her fourth baby when my mother was born. Hana came with her baby to Yaruga and stayed there until she could stop feeding my mother. I didn't know any of them, because Hana and Bencion died before I was born, and their children were lost in towns and cities during the revolution and the Civil War [1918-1921].

I also have some information about my mother's older sister Dina. Dina married a merchant of Guild I called Fishman. They lived in Odessa and had two daughters: Charna and Lisa. They also had sons, but I don't know their names. Dina was a French teacher at the school in Odessa. She died some time before the revolution of 1917. Charna moved to France in 1916.

My mother's brothers Moisey and Isaac were the closest to our family. Moisey was born in 1865. He studied the Torah and the Talmud. This was all he did in life. He wasn't very religious. He studied religion as a science. It was of much interest to him. They observed the main religious rules in the family, but it was more a tribute to tradition than their true faith. Moisey was married three times. I didn't know his first two wives. They died before I was born. I knew his third wife, Dora. Moisey died in 1935. He had five children. His two daughters of his first wife, Luba and Sonia, died in Mogilyov-Podolskiy after the war. His son and daughter of his second wife moved to France during the Civil War, and Abram, Moisey's youngest son, returned from the front to Yaruga [during World War II]. He died around 1960.

Uncle Isaac was a very intelligent man. His wife Frieda died some time before World War II, and his children, two sons and five daughters, moved to different towns. Isaac was alone in Yaruga at the beginning of the war. He didn't want to evacuate. He survived the occupation, and so did all other Jews in Yaruga: They were supported and rescued by their Ukrainian fellow villagers. Isaac died in Yaruga in 1975 at the age of 90. Isaac's children received higher education and lived in big cities. His son Ilia Goldenberg worked for the designer Korolyov 4. He built space centers in Baykonur [Kazakhstan] and Kapustin Yar [Russia].

My mother Leiba was educated at home. When it was time for her to get married (her parents had died by then), Moisey and Isaac decided to use the assistance of a shadkhanim - matchmakers. Shadkhanim wore a cap, a tie and a red necktie - this was how other people knew who they were. The shadkhanim had information about girls and young men in the surrounding towns and villages. They traveled to other towns to make initial presentations of the potential fiancés until it came to the arrangement of engagements, which again were followed by weddings. They charged money for their services in advance. There were plunderers among the matchmakers, who escaped with the money. My parents met one another thanks to a shadkhan. Uncle Moisey and Isaac prepared dowry for my mother; they had the wedding gown made for her and went to Berezovka to meet her future husband and make wedding arrangements. My mother didn't get any pieces of furniture or any other things from my grandfather's house, though. My Uncle Isaac told me that my mother and father liked each other from the first time they met. They had a religious wedding.

After the wedding my mother moved to Berezovka. My father worked at the mill. My mother was a housewife. My brother Mordukhai was born in 1910. He was named after my grandfather. Perl was born in 1913, and I was born on 10th May 1916. I received the Jewish name Shloime at birth, after my grandfather on my father's side.

When the Civil War began, there were raids by gangs 5 - the Reds 6, the Whites 7 and the Greens 8 were robbing Jewish houses, raping women and killing people. I don't know whether it had any impact on my family, but the general situation was very troublesome. My mother persuaded my father to move to Yaruga. She wanted to live in a place with a bigger Jewish population. They moved to Yaruga at the beginning of 1918. My mother was right thinking that they would be safer in Yaruga. Jews and Ukrainians always supported each other and got along well. The Jews formed a self- defense unit and defended their town along with Ukrainian supporters from the village attached to Yaruga. My father and his brother Liber were brave men and weren't afraid of anybody.

Once a gang of Denikin units 9 - twelve men on horses - came into town. They were drunk and began to chase young girls and scare children. They demanded vodka and food. While they were drinking, my father called Liber, and the two of them took away their rifles and beat them until they climbed their horses and left. Of course we knew that they would be back to take revenge, and so our families stayed in the mountains, it was a mountainous area where we lived, for about two weeks. The bandits looked for us, but couldn't find us, as our neighbors told my parents later. The locals brought us food and told us that bandits had been searching for my father and Liber in the mountains for a few days. The local guys that joined the gang were trying to talk them into leaving the area. They liked my father and were afraid of him. They said in Ukrainian, 'Gersh and Liber are hiding there. They will kill us'. After two weeks the Denikin units retreated, and my father and Liber returned to the town. I know this from what I was told. I was only 3 years old then.

My first clear childhood memory is of my wailing for my older brother Mordukhai. My mother was crying and people were in mourning. In spring 1919 he was operated on his appendix and got infected. He was ill for half a year before he died.

During the first years after we moved to Yaruga we had a pretty hard time. We didn't have a house of our own. My father didn't have a job. My mother's brothers, Isaac and Moisey, and my father's brothers, Gedali and Liber, were supporting us. My father's mother Bluma lived with us for some time after we came to Yaruga. After Gedali's wife died, grandmother Bluma moved to his house to help with the housekeeping. Some time afterwards she fell and broke her hip. My mother and Liber's wife Sima suggested that Bluma moved into one of their families, and that they would be looking after her. Bluma decided to stay one month with Liber and Sima, and the next month with us. She moved from one house to the other at the end of each month. She was treated with high respect in both families. It was a very wise decision of hers. It was usually my chore to bring her food and water. Once I refused to do it for whatever reason, and my mother explained to me that grandmother was the most important person in the house, and that it was a great honor to look after her. My grandmother died in 1924.

In the beginning we lived with Moisey and Isaac and their families, but later we rented an apartment. We paid about 400 rubles per month, which was a lot of money. It was my mother's dream to have a house of her own. My mother had a golden watch on a golden chain and a winter coat with fox fur. These were the two most valuable things my family possessed. In 1924 my father went to Mogilyov-Podolskiy and sold them for 320 rubles. My parents bought an old shabby house with a thatched roof from the miller for this money. Actually, they only bought a plot of land on which they could build a house of their own. However, there was no money left for that. Uncle Gedali brought us three horse-driven carts full of wheat and one with flour. He also gave my father 500 rubles. My mother didn't want to accept it, saying that they wouldn't be able to pay back the debt. Gedali insisted that we accepted what he was giving us. Thus, Gedali helped us to build a big brick house with a huge wine cellar. We didn't know that the time of collective property was approaching and that the vineyard wouldn't be ours.

We had four rooms in this house: a living room, a dining room, our parents' bedroom and a children's room. We also had a kitchen with a big Russian stove in it. There were sheds and a stable. My father liked horses. He used to borrow a starved horse from the collective farm and keep it for a month or so to feed it up, then return it to the collective farm and take another miserable horse.

My mother was always kind of a leader in our family. She decided that instead of doing random work my father should start his own business. My parents decided to grow wine. In 1923 my father took a loan from the Agricultural Bank, and in association with another farmer he bought a small plot of land. Wine wasn't grown in Ukraine at that time and they had to order it from France. In the summer of 1924 my father planted the vines. Vines yield grapes after four year. To make a living my father decided to start making wine. He borrowed money from widow Milshtein, who had three daughters and loaned money for her daughters' dowry at 3% per month. My father bought grapes and made very good wine. He learned how to make wine barrels and even sold them. My father didn't sell wine before Christmas when it became more expensive because of the season. He managed to pay back his debts and bought grapes again and again until the time had come to harvest his own grapes. However, there was a terrible rainstorm in the first year that destroyed our harvest. My mother cried, but my father felt very optimistic. He bought grapes again and made wine.

The following year we had plenty of grapes and my father made his own wine. But then collectivization 10 began, and my father had to join the collective farm. He was reluctant to give away everything that he had worked for so hard. He joined the Jewish wine making collective farm. [Jewish collective farms were formed for the Jewish population living in rural areas in the course of collectivization in Ukraine.] There were three collective farms in Yaruga: one Jewish and two Ukrainian. My father never regretted joining this collective farm. He was paid well for his work, and the people were hard-working and wealthy. My father was involved in wine- growing in the beginning, but later he switched to a more familiar activity and became a miller.

I inherited the love for our home from my mother. I especially loved Friday evenings - Sabbath. I still recall the smell of bread baked in the oven. The house was kept very clean. We scrubbed and washed the floors and whitewashed the ground floor. On Friday my mother made bread in the stove to last for a week, and challah for Saturday. She also made cookies and strudels while the oven was hot. She made food for Saturday: gefilte fish, tzymes 11, carrot tzymes and stewed cabbage. She put the food that she made for Saturday into ceramic pots and wrapped them in pillows and blankets. Some of the food was kept in the oven. My father came back home from work on Friday and I brought him hot water to wash himself. As soon as the first little star appeared my mother put on a shawl and lit two candles. There was wine on the table and a fresh challah. My father said a prayer for the wine and bread, broke off a piece of challah and dipped it into the wine.

On Saturday my parents went to the bes medresh [synagogue]. It wasn't allowed to carry a prayer book to the synagogue, and my father either left it in the synagogue on Friday evening or asked me to carry it for him. My father was a kohen. Once upon a time the kohanim were the priests who conducted services in the Temple. [In the First Temple, destroyed by the Babylonian king, and the Second Temple, destroyed by the Romans.] The kohanim had quite a few responsibilities. My father said a special prayer blessing the community. He was a very respectable man. Certain things were prohibited for a kohen: my father wasn't allowed to stay in the same room with the deceased, and he was not allowed to enter cemetery grounds. He said farewell to his mother and son standing outside the cemetery fence. On Saturday, when my parents returned from the synagogue, a Ukrainian boy came to make fire in the stove and put down the candles. The adults weren't allowed to do it. It was only allowed for children under 13 years of age. My mother took our Saturday lunch from the oven and we had a festive meal.

We observed all Jewish traditions and celebrated holidays at home. Although my mother wasn't fanatically religious she strictly followed the kashrut. Once my sister Polia fell ill with mumps. The doctor suggested to apply pork fat to her neck. My mother was terrified at the thought of bringing pork fat into a Jewish house. She ran to uncle Moisey, who was reading Jewish books all his life and knew all Jewish laws, to ask his advice. Moisey thought about it, looked into his books and told my mother that it was all right to violate the rules for the sake of a sick child.

I liked Jewish holidays - Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, and Chanukkah - very much. I don't remember the details of our celebrations and at the time I wasn't interested in the history of these holidays, but I remember the warm and festive atmosphere at home and in town on those days.

I liked weddings most of all. After young people were introduced to each other by matchmakers, their parents paid visits to one another to make arrangements for the wedding. Sometimes the weddings didn't take place because parents didn't quite like each other. The next step after introduction was engagement. Engagement was a party with many guests that were all dressed up. During the engagement the ketubbah was drawn up. It included all terms and conditions of the couple's future life, their house or apartment, and dowry. The wedding took place six months later. Invitations to the wedding were sent out in advance. All those who received invitations to the wedding prepared wedding gifts. Nobody ever discussed wedding gifts with the others. People gave the gifts that they could afford. Guests came to Yaruga from other towns and even as far as from Kiev and Moscow. They came with their children and elderly parents and stayed at the bride and bridegroom's neighbors and relatives.

The wedding started in the synagogue. The shammash erected the chuppah, four fancy carved posts and a velvet cover in the yard of the synagogue. The bride and bridegroom entered the chuppah and all guests walked around it seven times. The bride and bridegroom put rings onto one another's fingers. Afterwards wine was poured into glasses, and the guests congratulated the married couple. Then everyone went to the house where the wedding party was to take place and had a shot of vodka and sweets. Later dinner with all kind of food was served, and that was when the real party began. There was music playing and guests were eating, dancing and enjoying themselves until late.

When I was 4 years old, I went to cheder along with other boys of my age. We studied the basics of religion, Yiddish, arithmetic and other subjects. We studied at somebody's home, kids and teachers together, taking turns: one month we were at my home and the next month at somebody else's. We had vacations at Pesach and Rosh Hashanah.

In 1924 I went to the Jewish school in Yaruga. There were two schools in our town: a Ukrainian lower secondary school and a Jewish primary school. Since I could read and write, I finished primary school in a year. The Ukrainian school was also turned into a four-year school, and so I went to the Ukrainian lower secondary school in Subbotovka [3 km from Yaruga]. Every day I went to school on foot. In the season when roads were bad my father rented a room for me in Subbotovka. However, I went home every Friday to spend the holiday at home. My father didn't want me to return home when the weather was nasty, but I couldn't imagine to spend Sabbath at any place but home. My mother was always happy to have me back home. We spent Sabbath together, and the following day I returned to Subbotovka.

My mother wanted me to have the bar mitzvah ritual, which is performed when Jewish boys come of age, turning 13 and one day. From this day on a boy can pray with adults and can even get married. It sometimes happened that after turning 13, a young fiancé was taken to the family of his future wife. This family gave him professional education and provided for him until the young people got married - which often happened only a few years later. I wished to avoid bar mitzvah. I was afraid that if they found out at school, they wouldn't allow me to become a pioneer. But my parents insisted. I had a teacher that came to our home to teach me how to put on the tefillin. He taught me prayers and traditions, and we read the Torah and the Talmud. We had the bar mitzvah party on the Saturday following my 13th birthday. My mother was cooking the food and preparing for the party. That Saturday my relatives took me to the synagogue, where the rabbi said prayers and put the tefillin on my forehead. We had many guests, and my mother was very happy. By the way, I never became a pioneer. It wasn't mandatory at that time, and I wasn't really eager to become one.

After finishing school in 1930 I entered the College for Electrification and Mechanization of Agriculture, located in the town of Bar, 60 km from Yaruga. I stayed in the hostel for about six months and then ran away, back home. I was only 14, and it was difficult for me to be away from my parents and our nice, cozy home. My mother begged me to continue my studies, but I refused to leave home. I stayed at home for almost a year and spent most of my time at the frontier post [Yaruga was located at the border of Romania]. I liked to take care of horses and do the rounds with the frontier guards. It was my dream to become a professional military, but my mother was strictly against it. She insisted that I entered the Construction College in Mogilyov-Podolskiy in 1931. I lived with our former neighbor from Yaruga, Motia Shteinberg. My mother sent me some food - pancakes, cutlets, stew, eggs and strudels - every week.

After the NEP was over, the period of industrialization began. The authorities began to collect valuables and jewelry from the people for the development of industries in the country. It mostly applied to Jews. The first round of expropriation took place from 1927-28. At night - inhabitants of our town called this campaign the 'red night' - the chairman of the village council, the commander of the frontier post and the chief of militia went from house to house, demanding money and valuables from the people. They took money, jewelry, watches and silver kosher utilities. We didn't have anything of value, and the unit left our house empty-handed.

The second round of expropriation took place in 1931. They came to our house again, and my father said that we didn't have anything. After a few months my father was summoned to the frontier unit and arrested. They believed that we had valuables but were hiding them from the authorities and didn't want to give any to them. My father was sent to jail. I brought him parcels with food and things that he needed every day. The Jewish investigation officer, Belik, demanded that my father hand over jewelry and valuables by threatening him that he would be sentenced to long-term imprisonment and that the family would be deported to Siberia. Once, late at night, somebody knocked on the window. It was my father. He said that his inmates had advised him to give the investigation officer three golden coins. He was to give them to him on the following day. We needed money to buy the gold at the market, so I went to Yaruga at night to get money. I ran 20 km. I had a cup of tea at home and started my way back. I returned to Mogilyov in the morning. My father bought the coins at the market and took them to the officer. That way he bought his freedom.

The college where I studied was closed. I went to Kiev in 1932 and entered the Construction College. There were two departments in this college: a Jewish and a Ukrainian one. We studied the same subjects, only in different languages. There was no admission to the Jewish department, so I entered the Ukrainian one. I lived in the dormitory. I always missed home, but I understood that I had to get a profession. In the beginning I went to the railway station every morning to look at the sign 'Kiev-Mogilyov-Podolskiy' on the railcar, so that I could at least see the name of my hometown. Later I met new friends: Matvey Russanovskiy and Zinoviy Pugachevskiy - Jews, and some Ukrainian friends.

I became a Komsomol member 12, and we went to parades and for walks in Kiev together. I stopped observing Jewish holidays and traditions. It was out of fashion at the time. Besides, it was next to impossible to follow the kashrut rules in the dormitory. We were young and had a good appetite. We ate whatever we had. After finishing college I got a job assignment at the Khmelnik road construction site of the NKVD Road Construction Division 13. I worked for a year, but kept dreaming about the military uniform. I went to Leningrad and entered a military college there. I didn't tell my parents that I was going to Leningrad. When I told them that I had entered the college they got very upset, but they understood that I was old enough to make my own decisions. I finished a two-year advanced course in 1939. I got a job assignment in Field Engineer Battalion 239 in Chernigov.

About half a year or so later, our military unit was sent to Poland where, according to the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement 14, the Soviet forces occupied a part of Poland and the Baltic republics. The military division from Kiev lost about 1,500 militaries. Our battalion had no casualties. The local population welcomed us warmly. The Jewish population talked to me. There was anti-Semitism in Poland, and it was a surprise to them to meet an officer that was a Jew. They couldn't believe that people had equal rights in the Soviet Union.

At the beginning of the war I was at the new western frontier in Lvov, where our unit was involved in the installation of fortifications. I was acting as commanding officer, because the commanding officers had left for Lvov for a meeting the day before. Later I understood that that meeting was contrived. None of the officers that had gone there returned. They were either arrested by NKVD officers or captured by the Germans. Actually, the Red Army was beheaded before the war. In the morning of 22nd June 15 the soldier on duty woke me up. He said there was motion and the sound of engines on the side of Poland occupied by the Germans. At 4 o'clock in the morning the bombing began. We didn't know that it was the beginning of the war, but we prepared our defenses. We stood firm for two days and then we took to retreat. In Ternopol we boarded a train to Kiev.

We were sent to the north-western area of Kiev. My sister Polia married a man from Kiev, Jacob Sementsov, in 1938. Jacob was a Jew, and his real surname was Sohn. Since his father was a NEP-man he decided to change his name to avoid any problems in this regard. Polia and her baby daughter Nelia were in Kiev, and her husband Jacob was in the army. I asked my commanding officer for a truck and drove Polia and her daughter to the parents of my Jewish fellow soldier.

I soon found out that my parents would come to Kiev. My father had bought a horse in Yaruga and they came to Kiev on a horse-driven cart. My parents stayed with Jacob's parents, David and Nehama Sohn. I asked my commanding officer if I could go on leave and went to see my parents in Kiev. We met in Tolstoy Square in the center of Kiev. My mother hugged me and asked 'Sonny, have you killed many fascists?' It was the eve of Yom Kippur. My mother told me that she had bought a rooster. I bought ten loaves of bread at a store - I had my military card with me - and gave them to my parents. My mother wanted to save the bread for the holiday. I asked my parents to evacuate and promised to help them leave, but they refused. They claimed that they were too old to go. I said good-bye and returned to my unit.

Our engineering battalion got an order to blast the bridges over the Dnepr River. It was clear that Kiev was to be left to the Germans. On 18th September we made our way in the direction of Yagotin. On 19th September, when we were in the vicinity of Borispol, we found out that we were encircled. We managed to get out of the encirclement. We were followed by the fascists, and near Berezan we separated into smaller groups heading East. I was with my friend Lieutenant Gonelidze, a Georgian, and assistant doctor Edi Ruda, a Jew. From 22nd September until 3rd October we were on the way to the East. We went at night and slept in haystacks during the day. We ate rye, whet grains that we could find and drank water from lakes or puddles. On the night of 3rd October we settled down in a small grove for the night. In the morning we were woken up by the dogs barking. We were encircled by the Germans and captured.

The fascists beat Gonelidze and yelled, 'Jude'. He shouted back that he was not Jewish, but Georgian. They didn't believe him. I was beaten, too, but I pretended I was Ukrainian. 'Das ist Cossack', they said. [Cossack is an old expression for a Ukrainian.] Edi had a cap with a red piping, and they thought she was a commissar and beat her badly. We were convoyed to a clearing in the wood. There were about 150 other captives there. Most of them were refugees from Kiev. There were Jews among them. They were ordered to take off their clothes and shoes. Then the Germans harnessed all people to carts loaded with their dead militaries - ten to twelve Russians and four to five Jews were pulling one cart. Gonelidze was among the Jews. We were directed to pull the carts to a nearby village. Some Jews fell on the way, and the Germans were killing them. Over 15 people were killed before we reached the village. In the village all remaining Jews were shot. My friend Gonelidze perished with them. I never saw Edi again either. She must have been killed, too.

We stayed overnight in the barns, and on 4th October we got on our way, convoyed by the Germans. I escaped in the field when we were walking on a road between corn and sunflower plants. The Germans couldn't follow me because they couldn't leave the others. They shot their automatic guns, and that was it. Lieutenant Dotsenko escaped with me. We covered 80 km when we were captured by policemen that took us to a camp for prisoners of war. The camp was fenced with barbed wire and when somebody approached it they were shot by the Germans. We didn't get any food or water. Inside the camp there was a special area for Jews, fenced with barbed wire. Three times a day all other inmates were told to gather near the Jewish area. The Jews were forced to sing and dance. They killed all those that couldn't or didn't want to perform. On the 4th day all Jews were killed. The Germans brought in interpreters and policemen to search for Jews, political officers and partisans. There were my fellow soldiers among the inmates, but they didn't turn me in.

From there we were taken to the Borispol camp. I escaped from there with my friend Borovik. We covered 15 km and were captured again near the village of Vishenki. We were sent to the Darnitsa camp. From there the camp was evacuated farther West. I ended up in the camp for prisoners of war in Boguniya, Zhytomir region. Every day 180-200 inmates died of dysentery there. I got swollen up from starving. We slept embracing each other to stay warm. A few people died in the barrack every night. The fascists didn't know that I was a Jew. Fortunately we didn't have any washing facilities, because if I had to undress everyone would have known that I was a Jew. [Because he was circumcised.] I made the acquaintance of Kostia Ovchinnikov from Leningrad and Victor Strelnikov from Moscow, and we decided to escape.

Soon we got a chance to escape. The management of the camp needed geodesists to make a layout plan of the camp. I was a construction worker and offered my services. So did Kostia and Victor. We received a compass, paper, pencils and rulers, and we began to do our work. One of the facilities was outside the fence, and we were allowed to go there to perform our task. We escaped to the highway from there and ran away. This happened on 19th December 1941. I don't know whether it was the Jewish or Christian God that was helping us, but we went all the way across Zhytomir, Kiev, Chernigov and Kursk regions.

We were joined by other people heading East. There was even one German man, Ernst Fritz, who didn't want to be with the Germans. On 24th April we crossed the front line. We were separated immediately, and I never saw Kostia or Victor again. The commanding officer of the unit, where we arrived, received me because I had information about the enemy. He thanked me for the information, and then I was to be heard by special units regarding the possibility of my cooperation with the Germans. The hearing lasted eleven months. I was staying in prisons that were following the armed forces to Riazan, Borisoglebsk, Bryansk.

I kept writing letters to Khrushchev 16 and Stalin asking for their support, but it was all in vain. Their main argumentation was that I was a Jew, but managed to escape - this was impossible and could therefore only mean that I was a traitor and a spy. In spring 1943 a commission from Moscow came to the camp where I was. They selected 1,000 officers of all ranks. On Stalin's orders an assault detachment was formed. It was to be sent to the most dangerous spots at the front. We received identity cards, specifying the rank, and were taken to Podmoskoviye where we had to drill for about a month. Then we were given uniforms, weapons, digging tools, flak jackets and sent to the vicinity of Smolensk. We were to start attacks in front of our army troops. Within two months only about 150 of the 1,000 survived. I was awarded a medal for 'combat merits'. Then I received my officer's shoulder straps and was appointed engineer of the Rifle Regiment 12, Division 32.

On 20th September 1944 I was severely wounded on my right hand and leg in the vicinity of Riga. I was dismissed from the army and returned to Kiev. I went to the address of the Sohns' house. Their neighbors told me that my in- laws and parents didn't go to Babi Yar 17 on 29th September. They stayed locked in their apartment, but they were betrayed by the janitor of the house who reported them to the police. They were all shot in Babi Yar around 10th October. I was looking for this janitor all around Kiev. If I had found him, I would have smothered him with my own hands.

I found my sister Polia in Kiev. Her husband Jacob perished at the front. Polia and Nelia were in evacuation in Syzran, Kuibyshev region. Polia washed dishes there to make a living. Later she became the director of a canteen in a military hospital. When Polia returned to Kiev in 1944, her apartment was occupied by another family. She got a room in an outhouse in the yard. Polia never remarried. Her daughter Nelia graduated from the Odessa Agricultural Institute and got married. She lived with her husband and son in Odessa. Nelia got cancer and died in Odessa at the age of 36. Her son lives in Germany now. My sister Polia died in 1991.

I got a job as a construction foreman at the Pechersk Utility Services Department. I worked there a few years until the early 1950s. During the campaign against cosmopolites 18 and the Doctors' Plot 19, I was accused of betraying the state. A criminal case against me was started, and I lost my job. The case was stopped because I wasn't guilty, but I couldn't find a job. Nobody told me that it was because I was a Jew, but every time they had some argument why they couldn't hire me. However, I was finally hired by a construction man that was well known in Kiev. His name was Barengoltz, and he was a Jew. I worked with his organization - Ukrainian Road Construction - for over thirty years.

At the beginning of 1946 I visited Yaruga. I met my Uncle Isaac. He had survived the occupation. Yaruga was the only place where Ukrainians helped to save almost all Jews. There were no occupants in town. The former chairman of the village council, Strizhevskiy, was working at the commandant office in Mogilyov-Podolskiy during the war, and he warned his fellow villagers about the scheduled raids. When Germans or Romanians came to the village, Ukrainians went outside their houses to announce that there were no 'zhydy' [Jews] in their village. They gave shelter to their Jewish neighbors in their own houses. When the Red Army liberated the town, the Soviet authorities sentenced the village monitor, Korovianko, to ten years of imprisonment for cooperation with the fascists. He had personally saved dozens of Jews! My Uncle Isaac collected signatures of all the Jews in Yaruga that had been saved by Ukrainians and Korovianko, went to Moscow and managed to have Korovianko released. In Yaruga, Kuzma Bachinskiy told me that they were all trying to convince my father to stay with them in the village, but he was eager to reunite with his daughter. I couldn't stay in Yaruga for long. I had tears in my eyes and felt great pain in my heart. I left. I visited Yaruga last year when a film about the righteous men of Yaruga was being made.

In 1946 I married a Jewish woman, Sophia Baram. I met her visiting my acquaintances at the celebration of some Soviet holiday. Our family life wasn't a success, and I don't feel like talking about it. She was a selfish and sickly woman. We didn't have children. Besides, she got mentally ill and died in 1985.

My second wife, Elena Bobkova, is Russian. She comes from Bryansk region. Her parents died when she was a small child, and she finished secondary school at a children's home. She worked as a secretary in various offices. She didn't have an opportunity to continue her education. She was married, but her marriage didn't work out. She moved to Kiev at the invitation of the military registration office. They had heard about her diligence and wished to employ her. She lived in a communal apartment for some time before she moved in with me. Elena's son lives in Odessa. We get along well with him.

Elena remembers all Jewish holidays, she buys Jewish calendars every year and reminds me to buy matzah in memory of my parents. I'm an atheist and don't observe any Jewish traditions or celebrate holidays. It's too late to start changing now. On 29th September I come home earlier from work, we get flowers and we go to Babi Yar where my parents and many other Jews from Kiev perished. I know that many Jewish organizations have been established in Kiev lately. It's wonderful that people can communicate and get assistance. I don't go to any of these organizations. I can work and provide for myself. I still work and don't need their assistance, but I know that their support is very important to many people.

Many of my friends left for Israel or Germany. I'm always interested in what's going on in Israel, and I like the country. If I were able to leave and do something for the country I would. But I don't want to be dependent on anybody there. Germany is out of the question. I haven't forgiven the Germans for what they did. And in general, I shall not change my nationality, convictions or motherland.