Siima Shkop

Tallinn

Estonia

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of the Interview: March 2006

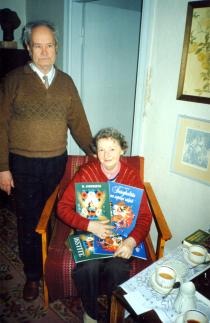

I interviewed Sima Shkop at home. She is living in the house, constructed by the Artists’ Council in Estonia, next to the citadel wall around the Old City. Siima lives by herself after her husband died. Though, she is not quite alone. A big well-groomed cat is living with her. Numerous pictures on the wall are painted by Siima and her friends. Siima is a petite lady. It is hard for her to walk, so users walkers for that. Siima has a heavy Russian accent. She switches to Estonian when her Russian fails her. Nata Ring, the secretary of the Tallinn Jewish Community 1 came with me for the first meeting as she interpreted for us. Nata is from Tartu like Siima. In spite of living in Tallinn for about 70 years, Siima loves Tartu, her native town. She told me a lot about the Tartu of her childhood. Siima has a tough character and I felt it right away. She did not like the fact that I do not know Yiddish and reminded me of that often. I came with another person for the second time. Siima must have gotten used to me and was more affable. During my second visit she offered me to take a look at her illustrations of children’s books. I was rapt by what I saw and it instantly changed my impression on Siima. Only a person, having the perception of a child, could create such sunny, fairytale pictures. The characters of the fairytale drawn by her looked as if they were real, alive. When it was cold outside and I felt blue, I remembered her pictures and smiled.

I did not know anybody from my father’s family. Father, Jacob Shkop, came to Estonia from Poland, when he was adult. His family stayed there. All I know is that my paternal grandfather Moishe was a high-class tailor. In general, Father and his relatives were excellent dressmakers. They were very popular. I never met them. Besides, Father never told me much about his family. I even do not know the names of his relatives. Recently I found some old notes, where I found out that Father was born in 1883. I do not remember the place of his birth.

Mother’s family lived in the Estonian town of Tartu. My maternal grandfather, Shloime-Meer Rozenko, came to Estonia from Lithuania, when he was a callow youth. Grandfather served in the tsarist army 2. At that time the term of service was 25 years, so even if Grandfather was drafted into the army at the age of 17-18, he must have been over 40 when he was demobilized.

Grandpa was very handsome when he was young – a blond with bright blue eyes. He did not look like a Jew at all. I remember one interesting case, when I was about 13, one man came to Grandfather from Germany. I even do not know who he was to him, but he collected information about Grandpa. In Lithuania, which was Grandpa’s motherland, some of the people who had known him since childhood said that Grandpa was a foundling, fostered and raised by a Jewish family. I do not know whether that’s true.

Anyway, Grandpa identified himself as a Jew. He lived like a true Jew: he was religious, observed traditions, went to synagogue twice a week. During the holiday period, he went to the synagogue almost every day. Kashrut was observed in my family since childhood.

I did not know my grandmother Siima Rosenko, nee Kaplun. She died long before I was born. She had diabetes. She must have been born in Tartu as there was a tombstone in Tartu cemetery with an inscription in Hebrew. I never came across the surname Kaplun among Estonian Jews. There are a lot of people with the surname Kaplan though. Grandmother also has a grave in the old cemetery of Tartu. It is written Siima Rosenko in Russian [Cyrillic] on her tombstone.

Grandpa Shloime-Meer was also a tailor, specialized in dress coats, which required strong skills. Tail coats were in demand in Tartu because it was a university town and that type of dress was needed for all kinds of events and costume parties, arranged by the student societies. There were rich students, who ordered tail coats and poorer students could not afford that, but still needed them from time to time, so Grandpa made tail coats for rental. I remember there were two large wardrobes with tail coats of different sizes.

Since Tartu was a students’ town there were a lot of Estonian and Jewish students’ corporations, thus there were a lot of events and people hired tail coats from Grandfather. Besides, he was an honorable guest at all celebrations. Very often Grandpa came home drunk. He was a very interesting man. He was not of a tall height, had a nice voice and great sense of humor. All people loved him.

His tail coats were popular not only with students. When Carlis Urmanis 3 became the president of Latvia, he ordered tail coats from grandfather. Grandfather was invited to go to Riga several times to make the tail coats for him. I do not know when Ulmanis met Grandpa – perhaps he studied in Tartu. Grandfather made pretty good money, which was enough to provide for the family and pay tuition for education. Grandmother was a housewife.

Grandmother gave birth to five children, four daughters and a son. The eldest was Sarah, born in 1880, the second Dina, born in 1882. My mother Rosa, the third daughter, was born in 1884. Another daughter Luba – Jewish name Liebe – was born two years after Mother, and then, finally, the long-awaited son, German, came into the world. His Jewish name was Solomon.

All children were raised Jewish. Only Yiddish was spoken at home. Of course, the grandparents and their children also knew Estonian and German which was common in Estonia. Sabbath and all Jewish holidays were marked at home; kashrut was observed as it was holy.

The five children got good education. All studied at a lyceum. I am not sure if it was a Jewish lyceum. Recently there was an exhibition in Tartu on the subject of education in Estonia. My son went to see it. There was my mother’s certificate stating her transfer to the next grade. My son said she had straight excellent marks there. In general, my mom and her siblings were very gifted.

I do not know where my parents met. All I know is that they had a true Jewish wedding in Tartu with the rabbi and chuppah. Soon after the wedding, Father found a job in Sweden and left there with Mom. Father did not work there for a long time and decided to immigrate to America. He got in touch with his pals, who were living there, and they talked him out of it. At that time there was an unemployment crisis in America and his pals wrote that it would be hard for him to find a job there. Mother was pregnant and wanted to give birth in Tartu, so they decided to come back.

In 1909 my elder sister Rachel was born. She was called Rika in the family. When she was one year old, Father found a job in Warsaw, Poland. He was fluent in Polish and welcomed the chance to work there. They did not stay there for long. The house, where Father’s workshop was, burned down, and my parents came back to Tartu again. There were four people in the family now. In 1911 my sister Masha was born in Warsaw. She was named after our paternal grandfather, Moishe Shkop. They rented an apartment in Tartu and Father had his workshop there.

During World War I, Father was drafted into the army, and he was in the lines for four years. He was contused, when he was in Manchuria. Father had serious heart trouble when he came back to Tartu after war. He had a great workshop in Tartu and was a famous tailor there.

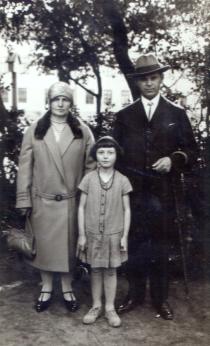

Mother was a housewife at that time and took care of children. When she got pregnant again, Father was sure that he would have a son. He was agog to see a son, but I was born in 1920. I was named after my maternal grandmother Sima. I do not know whether Father was disappointed that I was born, instead of a long-awaited son, but still he loved me very much and I loved him too. In spite of being busy, he paid attention to his children.

Yiddish was spoken at home, so I have known my mother tongue since childhood. Estonian was my other mother tongue, as my sisters and I played with Estonian children, who were living in our yard. It was natural for us to speak Estonian. Father was also fluent in Polish and Russian. His favorite writer was the Czech comedian writer Yaroslav Gashek. At home we had his book about a brave student Sweik. The book was in Yiddish and Father liked reading it to us. Father had a nice tenor voice. There was a Jewish drama theater in Tartu. There were no professional actors there, only talented amateur actors. The operetta ‘Silva’ was staged in the theater. I remember Mom and Dad often read in duet.

Father had another hobby – chess. There were some nooks in the theater where people could play chess. I remember Father took me to the café, where he bought me ice-cream and I was watching how he played chess. Father was good at chess and I also started understanding the game. In fact, Father liked taking me anywhere he could. When the first movie theaters opened up, he took me there.

Father loved reading and plied me with that since childhood. We had a very good library at home and Father also took me to the Jewish library in Tartu. We enjoyed getting together in the evening and read. Then we discussed the books and shared our opinion.

My parents were very sociable. Father had many friends. His best pals were those who were in the lines with him. My parents often went for a visit and we also received guests in our house. We kept the door open for people.

We sacredly followed Jewish traditions. Every Friday morning Mother cooked food for Sabbath. In the evening the whole family got together, Mother lit Sabbath candles, and we started dinner after having prayed. On Saturday morning Father always went to the synagogue. We marked Jewish holidays at home. We had separate Pascal dishes. Before Pesach there was a big cleaning in the house, chametz was taken out. Only after that Pascal dishes could be brought in. Of course, we obligatorily had matzah for the holiday. Father bought Pascal wine in the synagogue. We had two seders at Pesach: on the first and on the second evening of the holiday.

We marked other Jewish holidays as well. On Yom Kippur my parents and elder sister fasted. Purim was a double holiday for us as it was also Mother’s birthday. Mother baked hamantashen – triangular pies with poppy seeds and raisons. On Jewish holidays the whole family went to the synagogue. Father was on the first floor with other men. Mother, my elder sister and I were on the top floor. It was always very ceremonious. We wore our best outfits on those occasions. My parents also made contributions to charity, it was a matter of honor for every Jew. On holidays we visited our relatives and they came to see us.

That calm secular life was over in 1929. Father came back from the war with heart trouble, which finally killed him. Father was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tartu according to the Jewish rite. Mother did not work while Father was alive, as he could provide for his family.

We had hard times when Father died. Mother was a widow with three children and she had to make money. She learned machine knitting. She was very gifted and had a fine taste. She started taking orders in the store. They gave her wool and she knitted jackets, which were sold in the stores. When she learned how to work very quickly she took orders in three stores.

Mother’s elder sister Sarah helped us a lot. She was married, but had no children. She treated us like her own kids. Sarah was a seamstress and her first husband was a tailor. First, they had a sewing workshop. Sarah was a great milliner. She had excellent taste. She was taught sewing by the best tailors in Saint Petersburg. Sarah was an amazingly kind woman. I have never seen a kinder person in my life. She helped everybody, not only us, and people loved her.

Sarah was the only of my mother’s sisters who stayed in Estonia. Her sister Dina, a blue-eyed blond, married an Estonian German man, who was from Tartu. His name was Milts. He taught geography at lyceum. Shortly after the wedding, Dina and her husband left for Germany and settled in Bremen. Her three daughters – Gertrude, Krista and Inge – are elder than me.

The third sister Luba married a Jew from Tartu, a tailor called Meer Marshak. His brother, also a tailor, rented the second floor in the house, where we rented the first floor. In general, the family was big and all were tailors. All of them, including Luba and Meer, left for England, Liverpool, in 1921. When I was a child, I knew Luba only from pictures. I met her when she came to the wedding of my sister Masha. Luba did not have children. When Father died she assisted us with money a lot. Gertrude, Dina’s elder daughter, said that she helped them as well when life was hard in Germany after the war.

Both of my sisters went to lyceum: Rika to the Russian one and Masha to the German one. Jews often had their children study in the German lyceum, for them to learn the language to enable them to continue their education. When Father was alive, the family could afford tuition. Having finished school, my elder sisters Rika and Rachel entered Tartu University, the economy department. Then Father died, so Rika had to find a job to pay for tuition.

She worked for the Jewish bank in Tartu to assist Mom with money and to get more experience. At that time Rika studied hard at the university library. She met her husband there. Dovid Soliternik lived in Israel. He was one of the first to settle there. His family came either from Romania or Bulgaria. He was a young disabled man. He had an artificial leg, he worked with dynamite and his leg was blown off as a result of a blast. He was not fit for the army, so he decided to enter Jerusalem University, finished it and became a tutor.

A Latvian Jewish school invited him to hold a lecture course for students in Daugavpilts. At that time he was a professor, an expert in oriental languages. Dovid found out that Tartu library had ancient Arabic manuscripts and he came here from Latvia to read them. So he met Luba there. It was love at first sight – a great love.

They got married in two months. The wedding was in Latvia, under a chuppah. Shortly after the wedding Dovid came back to Israel with Rika. I do not remember the name of that small town, where they settled. They built a house. Dovid worked as a teacher. In 1936 their first child was born. They named him Jacob after my father.

My second sister Masha got married right after finishing lyceum. Her future husband, Aisek Reisman, was her classmate for eight years. They got married right after having finished lyceum. When Mother wrote a letter to Aunt Luba that Masha was going to get married, Luba came from England. She organized a great wedding for Masha and Aisek. It was a truly Jewish wedding with a chuppah. I do not know why they had a wedding in Valga. I can’t recall.

After the wedding, Aisik entered Tartu University. He studied and worked. Masha did not study as there was no money for tuition. She tried to learn some profession, but did not succeed. She was very smart, but awkward. She found a job as a sales assistant in a large store. They lived separately from us, but Masha always found time for me and called on us often. My sisters were both friends and nannies for me. They took good care of me as they were much older.

When my sisters were married off and left the house, Mother could not afford the apartment we were renting, and we moved to Grandpa. When Sarah got married, he stayed alone. Mother was the homemaker. Our living was modest, but Mother always found money to celebrate Sabbath and mark all holidays Jewish traditionally. She observed kashrut. We had kosher dishes. I remember she cooked vegetable soup and gefilte fish – Grandfather’s favorite dish.

Mother took me to the Jewish kindergarten. The teacher was the wife of the director of the Jewish school in Tartu. She taught Ivrit, and I still remember it. All classes were taught in Ivrit and Mother wanted me to learn the language and to be among children. I went to study when Father was still alive. He was getting more and more unwell, and there was a lack of money. That is why I entered Jewish elementary school.

The teachers were good. By the way, some of them later taught at the Tallinn Jewish lyceum. Our teacher at the first grade was Vilenskaya, a very beautiful lady. She taught me how to read and write. She and her friends staged plays in German at the school theater in Tartu. Then she taught German at Tallinn school.

We had wonderful teachers. One of them, Levitin, seemed an old man to me. He taught us Ivrit and the Tannakh in Hebrew. Of course, he did not tell us all the things, he picked only the subjects that we would understand, and covered the most important things. He also commented – sharing what one rabbi said on a certain subject and what opposite opinion was expressed by another rabbi, and we tried to find out which opinion was correct. Then I understood he did not only teach the Tannakh, he wanted us to learn how to think, analyze and have our own opinion, even it differs from the common point of view.

He also told us interesting stories, which I still remember. My teachers also arranged extra-curriculum activities. There was a school theater, we staged plays, gave performances dedicated to the main Jewish holidays. There were a lot of spectators – kin, friends – and all praised them. A school choir also gave a performance as well as the students of the dancing and gymnastics studio. The concert program was always very comprehensive and it was interesting for both – spectators and participants. One of our teachers, Levin, came here from Poland. He knew a lot of nice Jewish songs and taught us those. I have very bright recollections from school times. I kept in touch with many of my classmates after I left school. I studied there only for three years.

When I finished the third grade, there were not enough students to form another class. Thus we had to go to different schools. There were eight girls in my class, and the four of them, including me, went to an Estonian school. It was an elite school and the tuition was high. The teachers were great. I think Aunt Sarah covered the tuition there to help Mother and me. The four of us understood that there was a need to speak fluent Estonian and have no accent. We were the first Jewish girls who were enrolled in that school.

Of course, we were fluent in Estonian as we were constantly communicating with Estonian children, but our grammar was poor. In summer, the four of us crammed Estonian grammar. After hard studies, we learned how to write literately. Then at school it turned out that our Estonian was better than that of other students – Estonian native speakers. The Estonian language teacher respected us for having good knowledge of Estonian grammar. We also had a good German teacher.

I cannot say that we, Jews, were treated in a wrong way, but there were all kinds of incidents. Once, we came in the class and one girl cried out, ‘Jew!’ and pointed at me in front of the class. I was a small girl, but I could stand up for myself. I took a bottle of glue and poured it on her head. Then I beat her, though she was much bigger than I. The whole class was rapt! After that people had a very good attitude towards the Jews in class.

I and other Jewish girls had Lithuanian friends. Of course, there were times when the guys would push us in the street and say something unpleasant, but without spite. In general, the attitude was good. I did not feel hurt. We prayed on Monday before classes. We, Jewish girls, did not join the prayer, and waited by the door to the classroom. There was a prayer at the end of the school day. Once I also said a prayer in Lithuanian, but it was like a joke for me.

I started drawing in the Lithuanian school. We had a wonderful drawing teacher. Her lessons were always very interesting. She gave us the topic and we were supposed to draw something on that subject. At the end of the class she collected our drawings. She showed them to the whole class and everybody was to express their opinion on them. She did not teach us basic skills, but, the most important thing: she taught us how to look at things. Now, I think it is the most important thing for an artist is to know how to look.

My friends and I did very well at school. I understood that there could be no other way as tuition cost a lot of money. I tried being good even at math, despite loathing that subject. I studied there for two years. Sarah’s first husband died. She married a Jew from Tallinn and moved there. Sarah tried talking Mother into moving to Tallinn. Then she got sick and had to undergo operation. Aunt asked Mother to let at least me come to Tallinn. Mother could not decide on moving there as she thought it would be hard to get a job in Tallinn. Grandpa’s tailor’s work shop was still income-bearing. We decided that I should go to Tallinn myself and live with Aunt.

I entered the Tallinn Jewish lyceum 4. It has an interesting history. Tallinn Jews put money together to have the school built. In 1924 the lyceum was opened, and it is still there. Owing to the efforts of our Jewish community, there is a Jewish lyceum there now. There was an Estonian school during Soviet times.

At first, it was hard for me to study at the lyceum as the teaching was in Ivrit, but not the old Ivrit that I was taught at school, but the modern Ivrit, spoken in Israel. I understood almost everything, but could not speak myself. It was not hard during the classes. My classmates spoke Ivrit during the breaks. Then I started taking private lessons in Ivrit. My teacher was Michelson. I worked very hard and studied it for less than a year.

I liked lyceum a lot, both my peers and teachers. We had a very good class; unfortunately, most of my classmates are dead now. There were quite a few students from the school in Tartu in the Tallinn lyceum. The school in Tartu was a six-year one, so many students decided to continue their education in Tallinn.

Samuel Gourin was the principal: a tall, blond man with huge eyes. He was loved and respected. His daughter was also studying at the lyceum. She was a bit younger than me. Zhenya became an orphan as her mother died when she was two or three years old. Gourin taught general history. We did not have text books in modern Ivrit, so we took notes after him.

There was also a teacher who taught us Jewish history. We also were taught Ivrit literature and grammar. Our mathematics teacher was from Tartu. When my sisters were studying, he taught mathematics in both lyceums. Then he was transferred to Tallinn lyceum. He was a very good teacher.

I hated math most of all when I went to Estonian school, especially algebra I disliked. I did much better in math when I was studying at the lyceum, I even started liking it when I had a trigonometry course. It was interesting for me and I got good marks. Vilerinskaya, my first teacher at Tartu school, also taught here. She was the German teacher.

We had so many new subjects that now I am even surprised how we could digest it all. There were also subjects taught in Estonian: chemistry, physics, geography and of course Estonian literature and grammar. There was also a course of Russian language, which I did not know at all. I even did not know the alphabet, but my classmates read the books written by Pushkin 5, Lermontov 6 etc. in the original.

The Russian teacher was very handsome. He understood that I did not know Russian and he permitted me to read those books in Estonian so that I could understand what was going on. Of course, I read them with pleasure and found them very interesting. I needed to learn the basics of the language and one of my classmates helped me with that. There was one class where the subjects were taught in Russian, but the group was very small. There were also gymnastics classes. We did not have my favorite drawing classes.

The chazzan of Tallinn synagogue, Gourevich, taught music and Jewish traditions to us. He came to the classes with a small accordion and played it. We sang Jewish and Hebrew songs. Gourevich was very interesting and funny. His daughter, Anna, subsequently a famous Estonian pianist, Anna Klias, also studied at our lyceum. She was a good student. When I graduated from lyceum, she and some other Tallinn alumni were at the traditional reception arranged by our principal. The most outstanding student was always invited and there were always Jews among them.

Children from poor and rich families studied together and it did not affect the relationship. We did not choose friends by their parents’ income. We had our own company consisting of boys and girls. We went to dancing classes. In general it was our common interest. We wanted to learn how to dance beautifully.

All lyceum students were members of Jewish organizations. I was a member of the children’s Jewish organizations. In Tartu I was a member of Hashomer Hatzair 7. This organization was represented in Tallinn as well. A lot of my classmates were members of Hashomer. We took part in Estonian scout contests. In summer we went to Hashomer Hatzair scout camps. When we moved to Tallinn I entered the Jewish youth organization Maccabi 8. There were good gyms in that organization. I loved gymnastics. I started attending rhythmic gymnastics there. I had rhythmic gymnastics classes in Tartu, but they did not have such good facilities as in Tallinn. Our trainings took place in the university gym.

We, schoolchildren, were interested in politics. When the fascists came to power in Germany, we started boycotting German films; a lot of them were screened in movie theaters. We even refused speaking German, though most of us were fluent in this language.

I finished lyceum in 1938 at the age of 18. I wanted to go on with my education, and was dreaming of going to the arts institute. The tuition was very expensive, and I could not afford it. Aunt suggested taking me as an apprentice in her workshop, but I did not like sewing and had no skills for that. I decided that I would take any profession, but that. I became an apprentice of a famous hairdresser in Tallinn. Even the president had his hair cut there and the wives of all the diplomats were customers there.

At that time, when the fascists came to power in Germany, fascism was trickling down here as well. They even did not want to hire me for being a Jew, but still took me as an apprentice for two months. Then one of their regular customers – a wealthy Jew – stood up for me. She said if I was fired only because of my nationality then no Tallinn Jews would ever come to the salon. She was also supported by a rich German lady, who was also a regular customer. She said the nationality did not matter, the work did.

Unfortunately, during my apprenticeship I was more involved in cleaning than in training. When I had spare time I was standing by the master and watching his work – beautiful hairdos. Once a week I attended a special school where I was taught to put wigs on and do make-up. It was very interesting for me. When I finished school, I worked at the hairdressers’. Often I did not have to do my job, but be at beck and call for my customers, who were of different age – adult ladies and young girls like me. While they waiting in line, they could send me to fetch cakes from confectionary or run other errands for them.

When a customer was my age I sadly thought to myself – that she could do what she wanted – study and have no problems in life. I wanted to study, but could not afford it. I wanted to banish those thoughts, as there was nothing I could do. If I was too focused on that, it would make my life unbearable. I tried to have a fully-fledged life the best way I could. In the evenings I went to Maccabi for training. I dated a guy, my classmate from lyceum. My beloved and I went to the theater, cinema, dancing.

I also attended English language courses. Now I cannot picture how I could cope with all that. In a year I met a young man, an artist. He looked at my drawings from school and said that I should become an artist. I dropped my English language courses and went to the art studio instead. It was headed by Estonian sculptor, Voldemar Mellik. I attended evening art school courses. We painted nude models. In Mellik’s opinion I did pretty well. He said that I had to study at the institute, which I could not afford.

In 1939 my elder sister Rika, her husband and son came to Tallinn from Israel. Dovid intended to work in the library and Rika was happy to take advantage of the chance to rent an apartment not far from Aunt Sarah’s house. Then Mother and Grandpa moved to Tallinn. Mother moved in with Rika and Grandfather lived in Aunt Sarah’s apartment. There was not enough room for everybody, besides there was Aunt’s sewing workshop in the apartment. It was OK with me as I was out of the house most of the time.

I spent a lot of time in Maccabi. We had a wonderful rhythmic gymnastics trainer and we succeeded in our performance. We did not only tour Estonian cities we were also in Latvia and Lithuania. In 1939 we were invited to Finland. There was a large stadium in Helsinki constructed on the occasion of Olympic games, where in 1939 on the eve of the Soviet-Finnish War 9, an international gymnastics event was held with the participation of 300 Estonian girls and boys. Our nine ladies from Maccabi, including me, also took part in the event. The audience was pleased.

In 1939 Germany attacked Poland 10. The war was over shortly after Soviet troops entered Poland. Then the Soviet Union attacked Finland. We followed the military actions and were worried for Finland. We were very happy when the war was over as Estonia always had very good relationships with Finland. Then the Soviet government signed a non-aggression agreement with Germany [the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact] 11 and put pressure on the Estonian government to have military bases constructed on its territory 12.

Of course, at that time we did not know what it was for and felt calm. Many of those who were frightened of the intrusion of German troops in Poland even welcomed the idea of Soviet military bases in Estonia thinking it to be a pledge for peace. We knew that Jews were killed in Germany. By the middle of the 1930s there were quite a few fugitives from Germany. They said what was going on there. At any rate, our family feared fascists much more than the Soviet Union.

In 1940 Estonia became Soviet. In general, we had nothing against it as we knew hardly anything about Soviet life. All we knew were pretty attractive slogans. A lot changed when the Soviet regime was established in Lithuania. There were even changes for the better – the education was free, both secondary and higher. It meant that my dream to study at the Art Institute would come true. In general, there were a lot of new interesting things. My friends and I were fond of that. We discussed news.

I successfully passed entrance exams to Tallinn Art Institute, the art department. I did not have to pay tuition. Besides, I got scholarship. I could drop work and start studying. It was a happy year for me, 1940. I enjoyed drawing and the classes were not a burden, but a pleasure for me. I managed to cover a two-year program within a year. I studied only for half a year at the first course, attending the classes for the 1st and the 2nd course and passed exams for both courses.

As for the painting classes, I was in the group with the students of the 3rd course. Khapson, the best Estonian artist, taught us painting. He became my tutor. He was my teacher for the whole time. Khapson is still alive. He is 90 and he is still working! His workshop is in the house, where I am living. A museum with his paintings is also here. Our rector, Starkov, was a wonderful Estonian sculptor. He made sculptures from granite. After the war his workshop was in Tartu. Starkov was a very intelligent person, a good rector, treating the students very nicely. I was lucky to have such teachers.

Having finished the 1941 academic year, as per results of the exams, I was transferred to the third course. We had a Komsomol organization 13 at the institute and I joined it. I was a very young girl and was interested in many things. I also had some odd jobs – drawing slogans, pictures for wall papers. At times I had to work from dawn till night. I was friends with the students and did not have any problems with anybody. The teachers also treated me very well.

Of course, I was grateful to the Soviet regime, which let me study and do what I liked. At first, the Soviet regime did not oppress Estonian citizens in any way. Kolkhozes 14 appeared later, and peasants were not oppressed right away. Enterprises were nationalized, and taken away from rich people. There were no wealthy people among my acquaintances and family, so we were not affected by that.

We did not have our own apartment, but rented one. During the Soviet time, the houses were nationalized, but people were not evicted from their homes. At that time we had to share our apartment with another family. It was called communal apartment 15. Before we did not have anything of the kind – people living with strangers in the same apartment. But we abided by that and with many other things.

When on 14th June 1941, one week before the war, people were deported from Estonia 16, it was dreadful! I remember it vividly. Nobody was deported from our family, but we feared it! People shared with each other the news about deportation on that scary day and were afraid for themselves. Everybody understood that it was just a beginning. Most likely there would have been more deportations if on 22nd June 1941 Germany had not attacked the Soviet Union 17.

At that time I destroyed all photos which were connected with Betar 18, Hashomer Hatzair. At that time I understood that those pictures would be the evidence against me. I kept only some snapshots of performances of our Maccabi gymnastics group. I regret it so much; I should have hidden those snapshots.

Grandpa died two weeks before the war. He was buried in the Tallinn Jewish cemetery according to the Jewish rite. At that time we were mourning over him. Only later we understood how happy he was to die at home, among people who loved him, having been buried decently, not in a common grave in evacuation.

Rika and her husband left Estonia in late 1940. They went back to Israel. When we found out that the war was unleashed, we decided to leave Estonian immediately. In the late 1930s there were a lot of fugitives from Germany in Estonia, who told us that the fascists killed Jews. We understood, that we would be killed if we stayed. Without any doubts we packed our things within one night.

My brother-in-law Aisek, Masha’s husband and his brother headed for Leningrad. They escorted the Tallinn hospital, which was evacuated there. Aisik took our things and left. We agreed on a place where we would be able to find them in Leningrad. They left and in couple of days Mother, Sarah, her husband and her one-year-old son went to the train station. We took the train to Leningrad, but we did not reach there. At Kacha station we were rerouted to another train heading for Ulianovsk, Kuybyshev. They did not want to let Estonian fugitives into Leningrad.

We had no things at all as we had counted on getting them in Leningrad. We only had evacuation certificates and passports on us. The final destination was Kuybyshev, but we got off the train in Ulianovsk. Only several Estonian families got off the train there. At the evacuation point we were asked for our identification and intentions. Then we were sent to a local house in a kolkhoz where fugitives from Polish concentration camps were living.

After a while our family was sent to the kolkhoz Kremlevskiy, 25 kilometers away from Ulianovsk. My sister and I were given assignments for work at school. My sister was offered to teach German and I – to teach drawing. My mother and sister were fluent in Russian and I was not. Owing to my Russian teacher at the lyceum I knew the rudiments. I took children’s books in the library, read fairy tales, wrote out unknown words, asked for their meaning and memorized them.

It did not take me long to learn Russian, but I was not very literate. I am still ashamed of my Russian grammar. But still, I know something. It is a beautiful and interesting language. I like Russian literature particularly.

We lived in that kolkhoz for half a year. Our family was given a small ramshackle house, but we could not live there as it was teeming with bedbugs. We found a vacant room at school and moved in there temporarily. Then we were provided with a new lodging – a nice clean house not far from Volga. We lived from hand to mouth. We were saved by the under harvested crops in the fields – we picked peas, wheat ears and ate them. The locals also helped us, though they did not have enough for themselves.

By that time, my brother-in-law Aisik and his brother came. They took the patients and staff of the hospital and then they were free to go. They did not meet us in Leningrad, but found us via the information bureau for evacuees in Buguruslan. Aisik’s brother stayed with us and then all of us left for Ulianovsk. Aisik started working at the factory and rented a room from a Tartar for the whole family.

Тhere were a lot of Tartars in Ulianovsk. I liked them a lot – they were very kind and sincere. Russians were also very good people. But still there were some rascals, who informed the NKVD 19 against us saying to check our things. They searched our apartment, but of course they did not find any things that were banned.

In October 1941 the Germans came closer to Moscow. The commanders understood that they would not be able to stop the Germans and started making anti-tank fortifications. A lot of women and teenagers were involved in that. Those fortifications were made 50 kilometers from Ulianovsk. We were taken there by train.

We were followed by another train with young guys, who were heading for the front. There were even schoolboys among them. That trained stopped by ours. The ladies, who were heading for construction works, got off the train, hugged those boys and gave them some food they had. All of us cried, understanding that the guys were to face death. They did not even have rifles, and they were to be in the lines fighting against well trained and well-armed soldiers.

We were given spades, hoes for digging anti-tank trenches. It was cold, the land was frozen and it was very hard to dig. First we had to work with a hoe and then use a spade. We did not have a place to stay; we had to sleep on the earth. No food was taken to us. We even did not have bread for a week. We had to pick some roots and herbs in the forest nearby. An elderly lady and her daughter and some 13 to 14 boys evacuated from Leningrad were working closely with me. That elderly lady shared all food she had. I will never forget her.

We exerted our every effort, but there were hardly any results. In a couple of days the lady said that we should leave as our work was futile and dangerous for our life. We had to walk for 50 kilometers. It was a harsh winter. We walked along dug anti-tank trenches and the trip seemed endless to us. There were a great many people involved in digging.… We had been walking for a long time when we finally reached Ulianovsk. I got really cold and was unwell for a while. I almost died, but I had a young organism and survived without any medicine.

When I got better, I went to work at the military plant. There we were given food cards 19, which allowed us to get twice as much bread than for civil work. It was very important as there were three of us and I was the only one who was working. Mother and Aunt Sarah got dependent’s cards – 200 grams of heavy semi-raw bread per person. Of course, it was not enough. We were hungry, but the cold was even worse.

The parents and brother of Aisik lived in evacuation in Middle Asia. They often wrote to us and we knew that it was warm there. It was the main reason for our decision to move there. Mother, Aunt Sarah, my sister Masha and her son moved there first. Aisik and I were to follow them later. We were supposed to work for a certain time after submitting our notice.

I met Starkov, the rector of Tallinn Art Institute, in Ulianovsk by chance. He said that he had a lot of friends in Moscow, who taught at the art academy. He gave me their addresses. He told me to drop by them and say hello from him if I were in Moscow. He said they would help me continue my education in Moscow. At that time, I was not thinking of Moscow as I was on the point of leaving for Fergana [Uzbekistan, about 3500 km from Moscow].

We had been traveling for two months. We took the train heading for Fergana, but reached Samarkand. We had to spend a day there before we could take a local train to Fergana. I went to take a walk in the city. It was a beautiful and peculiar place. It was the first time when I saw oriental architecture and paintings. I hadn’t even seen that on pictures before. I was carried away and got lost. I asked for directions, but the local people did not understand me as their Russian was also bad.

I reached the mosque and noticed some people who did not look like locals. I heard them speaking Russian. I went up to them and asked where they were from. I learned that they were from the Moscow Academy of Art which was evacuated in Samarkand. I took out the note which I had gotten from Starkov and asked whether there was such and such a person among them. They told me that it was the rector and took me to him.

I said ‘hello’ from Starkov. He asked me about him and myself and suggested that I should stay in Samarkand and study at the academy. It was very alluring for me, but I decided to find my family first and then, if I had a chance, I would decide to move to Samarkand to study. They saw me off to the train station, but the train to Fergana had already left. The next day I went to the train station once again. There were no tickets, but crowds of people intending to leave, but failing for a number of times. I was lucky that a guy working at the train station took pity on me and pushed me in the car when the train was starting to move.

When I came to Fergana, I went to the evacuation point to ask where my relatives were living. It turned out that they had not reached there yet, though they had left much earlier than me. I happened to be in a strange city alone. A bullock-cart cabman took me to the market on the central street which was called Lenin, as it was common in Soviet times.

I started roaming about the city without knowing what to do. It was a miracle – I met my pal – a Jew from Tallinn, who was the only Jew from Tallinn evacuated in Fergana. There are such amazing coincidences! He suggested that I should live with him. I had stayed there for two weeks before my relatives arrived. Aisik also came after me. It turned out that his brother and he caught typhus on the train and were hospitalized in Samarkand. Aisik survived, but his brother did not.

We found a place to live. Mother and Aunt Sarah were very weak and elderly, so it was hard for them to work. I understood that I would be the only bread-winner of the family and started looking for a job. I found a job as a hair dresser. Before our departure, I took all the instruments with me, I even had rollers for making hair curly. I was gladly offered a job.

In spite of hard military times, I had a lot of clients. All kinds of ladies! The doctors from the rear hospital, wives of militaries, evacuees, women of easy virtue… All of them were very different, but willing to look good. Women wanted to remain feminine and I really liked the fact that I could help them. I made hair-dos. I tried to do my best especially when ladies wanted to have their pictures taken to be sent to their husbands to the front. I was very pleased when the lady showed me the letter from her husband saying how beautiful she looked. There were so few joys at that time, so I was happy for making someone feel good!

Apart from that work I also had some odd jobs. Twice a week I gave drawing lessons at the Pioneer House 21, made inscriptions on gravestones, painted posters, slogans. I worked till night. Then I got lucky. The Moscow theater named after Lenin was evacuated to Fergana from Moscow. I found out that there was a vacancy for an artist. I offered my services and was employed. I made posters, decorations. It was not complicated.

In 1943 I got a letter from the Estonian government. I was offered to go take classes at the art institute in a city in Bauhinia, near Oaf. Of course I felt so happy. It was my cherished dream. Mother and Aunt Sarah got food cards for dependents. There were few products and they would have died if I had not worked. I could not leave them by themselves.

Aisik, my sister Masha’s husband, was drafted into the army in 1942, when the Estonian Corps 22 was founded. He went through the war and finally he took part in the liberation of Estonia from the fascists. The Estonian corps liberated Tallinn from German troops and moved farther, to the islands. Masha often got letters from her husband. She got the last letter from him after his death. He was killed in action on Sharma Island. His elder brother Samuel told us about it after the war. He was a military doctor in the Estonian corps. Samuel saw Aisik walk into a mine field and he was blown up. After battles the soldiers of the Estonian corps buried their perished friends.

After the war Samuel took Anzac’s ashes from Saaremaa to the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn and arranged for a traditional Jewish funeral. In the 1970s Shmuel immigrated to the USA. Very few people from Aisik’s family survived the Holocaust. Some of them were killed in action, others murdered by Germans in Estonia.

We came back home in winter 1944. Estonia had already been liberated from the fascists. We had the certificate saying that we were evacuated from Tallinn and the militia in Fergana issued us a permit to go back. It was a long trip and we celebrated New Year’s 1945 in the train. The winter was very cold, and the cars were barely heated. When we came to Moscow, our train was on the sidetrack for ten days. It was 30 degrees below zero, and it was not much warmer in the cars. Then our train was help up in Leningrad for a long time. Finally we reached Tallinn.

Our and Masha’s apartments were occupied. By that time the wife of Shmuel Zaltsman, Masha’s husband’s brother, came back to Tallinn. She let us live in her apartment until we would get a new one. Estonians treated us very well. The neighbors took our things after we left and when we came back they returned all of them. We even did not ask for them. The brought our furniture and other things. Aunt Sarah stayed with Masha. Mother and I returned to our apartment. We shared one room, but still we were happy to be back. We were happy that our miseries and wanderings were over.

When we came back to Tallinn, I found out about the dreadful fate of three Estonian Jews, who were not willing to get evacuated. There were very many of them. People did not believe those atrocities committed by Germans, thinking it to be Soviet propaganda, concocted against Jews whom they hated. That is why many people stayed, in Tallinn in particular. Jews fled from Tartu; those who stayed were executed soon. It was scary! In Tallinn it took Germans a month to get all the Jews for execution. Men were kept in Tallinn prison, women and kids in the camp near Lake Harku 23.

I think many Jews stayed in Tallinn because of Rabbi Aba Gomer 24. He was the one who convinced Jews that there were no reasons for escaping from Germans, saying that it would not be worse than under the Soviet regime. He admitted that Jews might be oppressed in some way and restricted, but that he did not think that Germans, cultured and civilized people, killed Jews! Doctor Gomer and his family stayed in Tallinn. He was killed by Germans on the first day of the occupation. His entire family was murdered.

Mother had a friend from childhood. Before she met Father, she even wanted to marry him. That man stayed, because he could not leave his paralyzed sister. He was killed on the street. Some of the local citizens pointed him out to the Germans – ‘Here is a Jew!’ – and he was shot at once. There were many stories like that. So many of my friends and pals from lyceum and Maccabi died. Some of them were killed in actions, others in Tallinn…

Not only the Germans exterminated Estonian Jews. At the beginning of the war mother’s brother German Rosenko perished. When we came back to Tallinn, we got the documents of his death. It was a story, which was even covered in the newspapers: a common grave with 40 cadavers was found in the prison yard in Tartu. They identified the names of the perished and German was among them. Nobody doubted that they were shot by Germans. Only many, many years later we found out the truth. Those people were arrested by Soviet people before the outbreak of war. We do not even know the grounds for German’s arrest. Now it is not important. They were executed by the Soviet regime before the German occupation of Estonia.

Some of my pals from gymnasium got back from evacuation, from the front. One guy whom I was seeing during my studies at the lyceum also came back. We even wanted to get married after the war. He was drafted into the army during the first days of the war. He was a military interpreter, then he was a reconnoiterer during the blockade of Leningrad 25.

We wrote to each other during evacuation. Once I sent him a letter with pictures of me and my friend Reima who studied at Tartu school with me. She was in evacuation in Fergana, so we met there. In his letters he told me that the Estonian should write letters to him. I gave Reima his field address and said, ‘Write to him.’ At that time I did not know that I destroyed my love with my own hands. Reima was very beautiful and my friend liked her. They often wrote to each other. After the war he found her and they got married. It was a shock for me. Before going to the front he told me to wait for him and I did. He did not keep his word. My pain is gone and good reminiscences are left. Finally, he brought a lot of good things in my life. In early 1970s Reima and her husband left for Israel.

Shortly after our return I resumed my studies. The Art Institute was open again and the rector, Starkov, came back from the evacuation. I did well, even got my scholarship increased because of excellent marks. I met my future husband, Victor Mellov, during my studies. My classmate Markovich came back from the front and found me. He studied at the legal department of the university and Victor had studied with him before. They were friends and Markovich introduced me to him. We liked each other and started dating.

Both of us were very busy and we saw each other seldom in the evening. We had to get ready for our studies. Usually we met in the morning on the way to classes. We walked, talked and sometimes got so carried away that we were late for classes. We did not want to part. We decided to get married, but both of us were studying, had no money other than the scholarship, and no apartment. It was not the only obstacle.

Victor was Estonian, born in 1924 in Tallinn. His father was a joiner, his mother did not work. His natural mother died young and Victor wars raised by his stepmother. His fate was very hard. Victor went to the lyceum, but could not finish it as he had to work. He worked in the harbor as a sailor on a small ship. When Germany attacked the USSR, Victor understood that Estonia would also be occupied soon. He and his friends were concerned and they decided to reach Finland by boat. Of course, it was a crazy idea, but they succeeded.

Victor was not in the camp of Estonian fugitives in Finland. His relative lived in America. He was the captain of a ship. Victor decided to take a ship to Sweden, wherefrom he could get to America and find his relatives. Victor and his friends were captured by Germans in Finland. They said that they were Estonians and the Germans took them to Tallinn, to Patarei Prison. Victor was there for eight months. He was afflicted with typhus and was about to die.

In 1944, when the Germans started forming the Estonian legion SS, they mobilized Estonians. They also took some Estonian guys from prison. Victor was released from prison and mobilized. I do not know what would have happened to Victor, if his parents had not interfered. They persuaded an Estonian surgeon to operate on Victor and remove his appendicitis. While Victor was in hospital, the Germans had left Tallinn. Thus, he was saved.

Later, Victor wrote in his books: ‘No matter what adversities people have to experience, human relations are always there, and people help each other all the time. If you cannot find a way out – talk to people and they will always help you.’ This topic is covered in all of his books and it is well written. He is a very talented writer. The fact that Victor was in Finland during Soviet times, was in his ways. He did not conceal this fact and openly wrote about it in his forms. The Soviet regime found it very suspicious, as they did not know what he was doing there … In general, all people who were abroad were under suspicion. That is why Victor was not admitted to the Party, even though he was a Komsomol member.

I cannot say that Victor’s parents were happy about our intention to get married. They had a practical vision: both of us were students, whose scholarship and odd jobs would not be enough to get by. Besides, we did not have a place to live. My mother was flatly against my marriage to an Estonian. She did not think of the material side of things. Aunt Sarah was also against it, but not as ardently as mother. We argued for a long time, and eventually Mother told me, ‘Leave, and you are not our child any longer.’ I cried, but still I did not want to let my beloved go. We got married in 1947.

Of course, we did not have a posh wedding. It was the time of hunger and the attitude of our kin did not allow us to feel like having parties. After the registration of our marriage we came home, to the room where I was living with my mother. The three of us shared one room.

I finally resumed my previous relationship with Mother only after my son Oleg was born in 1949, when I finished my studies. Oleg reconciled us all. Mother adored him and Victor’s parents also liked him a lot. In general, they were happy to have a grandson. Victor’s Dad met me in the maternity ward and led me to the car supporting me. My father-in-law was a good person. He often sat in for my pictures.

My mother helped me a lot. She took care of my son Oleg and loved him. When in 1956 my daughter Zoya was born, Mother did not like her as much. She took after my mother-in-law: fair-haired, gray-eyed. Oleg looked like my father. I chose Russian names for my children. During the war the novel ‘The Young Guard’ 27 by Fadeyev 26 came out, and we enjoyed reading it. The main character was Oleg. I named my son after him. My daughter was named after the famous partisan Zoya Kosmedimianskaya, who was shot by Germans. My husband did not mind that, but our relatives were not pleased. My aunt wanted my kids to have Jewish names and my husband’s kin – Estonian. Anyway, none of them bore a grudge.

It was difficult for me to find a job. It was a hard time for the Jews: the campaign against cosmopolitans 28, streamlined state anti-Semitism. When I was a student, I started making posters, took part in the exhibitions, even got a prize for my poster devoted to the Days of Estonian Culture, taking place in 1947 at Tallinn stadium. Besides, I liked making illustrations for books, especially for children.

Upon graduation, I sought a job with a publisher of children’s books. I was given an assignment for probation – to make illustrations for fairy tales. The art council approved of my work, but still I was not hired. The director did not like Jews and did not even conceal it. Only several years later, when another man was in charge of the publishers’, I was hired. I made posters dedicated to some memorable dates, events, but mostly they were political. I made many of them. Each of my political posters was to be approved by the central commission of the communist party of Estonia. They were supposed to put a stamp on my sketch with a note that it was ideologically correct.

I never held back that I was a Jew. Knowing that in the Soviet Union it is dangerous to keep in touch with relatives abroad 29, I still mentioned in my forms that my sister was living in Israel. I was never persecuted, even during the campaign against cosmopolitans. When I finished the institute, I joined the Party right away and I became a member of Artist Council of Estonia. I did not have any conditions to do my job – the three of us were living in one dark small room. When I received a prize for my poster, I was given a room in the graphics workshop. I think that in Estonia the campaign against cosmopolitans was not as spread as in other parts of the USSR.

In Estonia the Soviet regime mostly struggled against Estonian nationalists – they were considered to be protesters against Soviet occupation. I think those nationalists were randomly selected. The rector of our Art Institute, Starkov, was accused of nationalism. I took the floor against his expulsion during the general meeting of the members of the Artist Council. I said that I had known him for many years and he had never dealt with politics and the things he was accused of, that he just always worked on sculptures. I said he was a great sculptor, a wonderful teacher and Estonia should take pride in him.

My speech got fervid feedback in the Artist Council. The secretary of the party organization called me on the carpet and said that I was wrong, going against the Party. He demanded that I should take my words back in public. I was called twice to the central party committee and every time I left a letter where I indicated that the charges against Starkov were spurious. He was a great rector and teacher. None of his student can say a bad word about him. I thought that at least they would expel me from the Party, but to my surprise it did not happen. I was in constant fear.

In 1948 there was the second deportation of Estonian citizens. This time the farmers were deported – those people who worked from dawn till sunset. Collectivization started in Estonia 30. In the USSR it took place in the early 1930s, but Estonian peasants did not want to join kolkhozes. It was not common for us. Peasants lived with their families on separate farmsteads. Those who were against joining a kolkhoz, were deported.

It was harder for me in early 1953, when the Doctors’ Plot 31 took place. Estonia was also affected by that. Anti-Semitism was broader. There were a lot of people from the Soviet Union who came to Estonia after the war. They did not doubt a single word spoken by the Party. If the Party said, it was true that the Jewish doctors were murders, then this inferred that all Jews were bad.

At that time I was a member of the board of Artist Council, and dossiers of some of the Jewish artists were under consideration at our general meetings. I was not called for such meetings but still I got many anonymous insulting letters. My husband also got defamatory letters saying how he, an Estonian, could have married a Jew. After that there were rumors in town regarding the deportation of Jews. Some even said that special trains heading for Siberia were ready for the Jews. It was scary. I was sure that I would be deported. Not only I, but my mother and aunt would not stand that trip. Those were hard times! Thank God, we got away with that.

I vividly understand that only Stalin’s death saved us. When I found out about his death, I took it as personal grief. I understood that something was wrong in the Soviet Union, but I did not associate it with Stalin. I sincerely believed that we survived the war owing to him, thinking that he took care of us, USSR citizens, doing his best for us to have a good living. I thought his death a tragedy for me and for the entire country. I cried, and other people as well. I had a feeling as if a close person had died.

An even bigger tragedy for me was Khrushchev’s 32 speech at the Twentieth Party Congress 33. At first, his speech was not published and even party members did not know what had happened. Then his speech was partially covered in the press. When I read it, I was almost killed by the news. The people who were in exile during the first deportation in 1941, started coming back. There was another deportation in 1948, when the peasants unwilling to join kolkhozes were deported. Those few who survived the Gulag 34 also came back.

Their stories were full of horror! So many people were killed, so many worthy people were sent to the camps by Stalin! Terrible! Probably some people knew about it when Stalin was alive, but they were afraid to talk about it. Most of them preferred to keep their mouth shut. It seemed to us that the NKVD controlled everybody’s life.

At any rate there was a constant interference in the life of our family. During the war my husband was in Finland and he was always blamed for it. I was not trusted either: I had a sister in Israel and according to the Soviet notions I could not be trusted. After the war Rika and I did not write letters to each other, as we were afraid. Soon we resumed our communication. Of course, I understand that our life in the Soviet Union was not quite right: we depended on NKVD actions, having fear all the time, but still nobody said anything and neither did I. After the Twentieth Party Congress my belief in the Party was undermined. I understood that I should quit as it would be hard for me to find a job.

After Stalin’s death I never felt anti-Semitism. My colleagues always treated me very well. There was no biased attitude to the Jews in the Artist Council. But my children at school often were told by their classmates that they were not pure Estonians, and their mother was a Jew. I found out about that when they grew up. Probably they did not want to get me involved.

We lived in a poky room, which was humid. My daughter had lung problems. She had to be in a sanatorium for two years. When the Artist Council built the house in the center, close to the Old Town, I was given an apartment there right away. All of us moved into the new apartment. At first we lived there with my mother; Aunt Sarah lived with my sister Masha. When Masha got married, my aunt did not get along with Masha’s husband. They had arguments all the time. Then my mother moved into Masha’s place and Aunt Sarah came to us. When Victor’s father died, we took my mother-in-law to us. My mother died in 1978. She survived Aunt Sarah by one year. Both of them were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn.

I worked a lot. I took part in many exhibitions in Estonia and all over the Soviet Union. I was awarded prizes twice. I painted a lot, made portraits of my relatives and friends. I did not give that up when I was employed by the publishers for making illustrations for books. I remember I made a portrait of Eri Klias, son of my pal from lyceum, Anna Gourevish, married name Klias. Eri went to music school and I made sketches during his classes. Then Eri became a famous conductor. I also painted a daughter of my pal from Tartu. Later I took her picture as a prototype of Snow White in illustrations for this tale. Now Anna takes her granddaughter Diana to me. She is the daughter of Eri and my Snow White.

My husband also worked hard. He wrote a lot. His pen name was Andres Valaa. He did not have a lot of spare time, but still he did not want to spend it in the family. He liked loud parties and gambling. Of course, it was not easy for me, but on the other hand he was an interesting person and I loved him. Victor’s friends were also very interesting people. I did not mind if they came to us. It was very important for me that Victor treated Jews with deep respect. He had no drop of anti-Semitism in him.

I raised the children. We did not follow Jewish traditions at home. Mother and Aunt marked Jewish holidays and we always went to Mother on holidays. The children knew about the holidays and how they were traditionally celebrated. When they were young, they took no interest in religion and traditions. My daughter is still not religious. When my son reached his mature age, he started being fond of religion and traditions. He felt himself a Jew. Recently he and our rabbi took a trip to Israel. They had to spend the whole night at Paris airport waiting for the connecting flight and were talking. The rabbi told my son that he was a true, pious Jew. My Oleg was impressed by it.

My daughter, like me in childhood, liked dancing. She entered a choreography school and finished it successfully. She was talented and she was offered a job in our theater, the ‘Estonia.’ She did not become a prima ballet dancer, but still she was rather famous. Her ballet career was short. She could not dance any more after she had a leg injury. Zoya entered drama school and then worked in the theater again.

In my opinion, she was not very lucky in her private life. Her first husband, one Laasik, was a very gifted actor. In 1975 their son Lauri was born. Then Zoya’s husband started drinking and they divorced. Zoya’s second husband was Chinese, an acupuncture expert. His ancestors came from China and he was born and raised here. His last name was Lei. Their son Ran Ananda was born in 1980.

Both of my grandsons are very good. Lauri is very gifted. He studies at the producers’ department. He is handsome and athletic. He is married and has a child. Sometimes he calls on me. Lauri is living in Tartu. Ran is working in construction. He is also a good boy. He served in the army. He wanted to be a pilot, but he could not enter pilot school because of unfinished secondary education. He dropped his studies at the lyceum. Zoya bought a farmstead, where she is living now. She liked the countryside since childhood, enjoys growing things. Of course, she does not do it all the time. She has a grand piano and she plays. She also teaches choreography to children. She is pleased with her life now.

When Oleg was young, he was fond of technical things. Then all of a sudden, art appealed to him and he entered the design department of the Art Institute. He graduated from it and started working. He married a wonderful Estonian lady, Ene. She graduated from the architecture department of Tallinn engineering institute. She is a very good girl. I love and respect her as my own child. Ene makes wonderful puppets. Oleg and Ene lived with us for a while after getting married. In 1972 their daughter Saave was born.

When my granddaughter was born, I retired as my help was needed. I enjoyed taking care of the baby. In 1978 my second granddaughter was born. My son insisted that she should be named Sima. According to Jewish tradition children are named after deceased relatives. When I wrote to my sister Rika in Israel that my granddaughter was named after me, while I was still alive, she said that it was a big honor for me as I was alive and my granddaughter was carrying my name. Alexander was born after Sima, in 1980. The youngest, born in 1983, was called Jacob after my father. I took care of all of them.

Now they are adults and have their own lives. The eldest granddaughter Saava lives in England. Her husband is British. She and her husband are philosophers. Sima and her family live in Israel, but both of my grandchildren are studying in Tallinn. I am happy for both of them. They are not drunkards or drug addicts, but good people. They come to see me. Ene also comes often and calls me. In spite of the fact that Oleg and Ene are divorced, I get along with her.

Now Oleg lives in Tartu with his second family. He has two children in his second marriage: daughter Kolla, born in 1999, and son Pele, born in 2001. Kolla is finishing the first grade. She loves dancing. Pelle still goes to kindergarten. He likes drawing the most. He says, ‘I am an artist now.’ Indeed, he is very talented.

For a long time I was not in touch with my elder sister Rika, who was living in Israel. After work we kept in touch for a while, and dropped it when the Doctors’ Plot commenced. I did not know anything about Rika for a long time. Then she found me via the Red Cross and we started keeping in touch again. Rika wrote that her husband died and she got married again. Her second husband was called Kron. Rika’s elder son Yakov taught at a school for handicapped children. Then he became the principal of that school. Rika’s husband was a politician and she was interested in that. Her second husband also died soon and she became a widow again. She never married again, but lived with her daughter and worked.

When Jews started immigrating to Israel, I was not going to leave anywhere. The matter is that my husband was a Lithuanian, a Catholic. I could not picture my life in another country. This is my country, the land of my relatives. My sister Masha and her husband left. Of course, I did not judge anybody; everybody has the right to make their own decisions. I always followed the events taking place in Israel, especially during the wars. First my sister Rika, who was not only a sister, but a friend to me, then my sister Masha moved there.

Of course, I wanted to see the country and my sisters. I managed to go there only in 1995. At that time I told my husband, ‘If I do not go now, I never will.’ It was hard for me to be there. I went in April, but it was sultry. I could barely stand the heat. In general, the atmosphere in Israel was strange for me. I know and love Ivrit and Yiddish, Jewish literature, but I am used to Estonian culture, to aloofness of some kind. If I were younger, it would be easier for me to adapt, but at my age it is impossible. I would not be able to live there. If I had to escape there from horrors and war, I would go there, but still I would miss Estonia, its cold sea.

I liked Jerusalem a lot, its ancient architecture. It is an amazing city. When I was by the Wailing Wall, I felt ashamed in a way. I wanted to feel that I was at the sacred place for Jews, but I could not feel it. It was not mine. Estonia was mine. I love both Estonians and Jews. Maybe it is not normal. Both of my sisters got wonderfully acclimatized in Israel. Masha is no longer alive. She died in 2004.Her husband is still alive. He gets by very well. Rika is living in a nursing home. She is 96. Last year my son went to Israel and visited her. She does no seem to understand what is going on. Oleg brought her picture. It is hard to recognize her – a little old lady with snow white hair. She always dyed her hair.

During the Soviet times I could not leave the country. I could travel anywhere throughout the Soviet Union, but I could not even think of going overseas. I traveled a lot across the country. I was in Latvia, Lithuania, Kiev, Moscow, Leningrad, and even had friends there. My husband and I went on vacation to the Caucasus and Crimea. I had friends from other countries.

Once I thought that the Jews from the Soviet Union were only Jews by birth. It seemed to me that they were completely assimilated, did not know the language and the rites. There was one case which made me think better. I often went to the Artists’ Houses, which existed during the Soviet times. There we could work and then relax. It was a combination of recreation and work. Once I was in the Artists’ House in Palanga, Lithuania. There were a lot of illustrators from many Soviet cities – Moscow, Leningrad, Minsk, Kiev, Tbilisi. All of them were very good. We celebrated New Year together. We had a nice and big cake, champagne. I started singing old Jewish song in Ivrit. After the applause, I asked them if they knew in what language I was singing. I was very surprised to hear that all of them knew as they were Jews!

My first trip abroad was to Paris in 1975. There was an international conference of the artists and writers, who are working for children. I could not imagine that I was allowed to go there. I always wrote in my forms that my sister was living Israel, which made me unreliable automatically. I was very surprised when the central committee of the party in Estonia proposed my candidature to the Artists’ Council. I went to the committee, to the person who suggested that I should go. He turned out to be a nice person. I honestly told him that my sister was living in Israel. How could he risk sending me there? I did not know if he was aware of that fact and I did not want him to get into trouble because of that. He smiled at me and that was it.

I did go to Paris, though I could not believe it. The conference took place in the UNESCO premises. It was very interesting for me. I was present at all meetings, and took notes. It was strange for me that most of the people who came from the USSR, were not interested in the conference. They skipped the meetings and strolled along the city. When the conference was over, French people organized a tour in Paris as well as excursions in three cities of France. I wished I had known French!

I was happy to meet our relatives, who were living in Germany – the daughters of Mother’s sister Dina. She married a German and left for his home country. Before the war, Mother wrote to Dina, but after the war it was impossible. Those people whose relatives were living abroad were very suspicious to the Soviet regime, but their relatives being in Germany was almost a crime. Thus we did not know anything about them. Only after perestroika 35 they found us.

I went to see them and my son also went for a visit. Then Dina’s children came to Estonia a couple of times when Dina was not alive any longer. I do not remember when she died. She was past 90. I met three of my cousins. I stayed in Bremen with the family of Dina’s elder daughter Gertrude Ossa, and the rest came to Bremen to meet me. Gertrude studied theology and her husband was a pastor at an old interesting church in Bremen.

The middle daughter Inge looks like her mother did in her youth: bright blue-eyed blond. Inge is a ballet dancer. She had her own ballet school. During the war Inge went to the front to the German soldiers with the performances. During one of her concerts she met her future husband, who was an actor. It was amazing that all of them managed to survive in Germany during the war. Inge said that her father quit his job during the war. He was a teacher and many people in town knew him. Some people might remember that his wife was a Jew. So he went to live in the forest and worked as a forester. Then they moved from one place to another.

The younger daughter Krista had no idea whatsoever that her mother was a Jew. She was even a member of the Hitlerjugend 36. I also met her. She lives with her family in Canada, but came to Germany to see me. Krista’s husband was a tank man during the war. His tank was on fire, but still he survived, despite of severe burns. He had face lifting operations over a period of two years. Krista was working at that hospital as a nurse, when he was there. They fell in love with each other and got married. They have many children. All of them are living in Canada. Krista’s husband is an optician. He is working for a large company, which produces complex optics. I keep in touch with my relatives. We talk and visit each other.

I started taking an interest in politics when I became older. It all started from Perestroika, Gorbachev 37. What an interesting life we had! Of course, even before perestroika we had much more freedom in Estonia than they did in other parts of the USSR. We were better informed as we were listening to Finnish radio and watched Finish TV. Thus, we knew what was going on in the world and in the USSR. I was delighted by perestroika anyway.

When Gorbachev went to England to meet Margaret Thatcher, I was pleased that she was interested in his visit. Gorbachev was a new type of Soviet politician and I liked that he was a smart and well-mannered man. I liked his spouse as well. She was interested in art and was knowledgeable about it. She was not a mere shadow of her husband, but a personality. They were given a very warm welcome during their trips abroad. I liked it. I started following the news, reading newspapers. Gorbachev brought a lot of interesting things into our lives.

My husband died two years ago [in 2004] after a long disease. He was buried in the Tallinn cemetery, where famous people – writers, actors and politicians – are buried. I have been on my own since then.

At that time, when Gorbachev was at power, the Jewish community was founded. Now it seems to me that it has always been there. It is hard to imagine our lives without it. We really need it. There are such wonderful people there. It is hard to work there! But everybody does his/her job very well and with pleasure. There are even non-Jews who are working there, but they are so dedicated and caring!

Now I do not leave the house and use walkers if I have to go somewhere. The cleaning lady from the community comes to me. She is not a Jew, but still we are friends. The community is wonderful! I wish I could go there more often, which I could do earlier. I used to go there on all Jewish holidays. Once a month the former students of the Jewish lyceum, who studied there before war, get together. Those meetings mean a lot to us. There is not always a chance to meet with your pals for a talk. Everybody goes there, if he physically can.

My exhibitions were held in the community building as well. When I turned 80, my jubilee was celebrated there and an art exhibition was arranged. I invited all my fellow students, who were still in Estonia. Even some of the teachers came from the institute: Olpert, who taught black pencil drawing and Olkaf, who taught painting. I gave one of my pictures to the community. I am happy that it is there and can be seen by many people.

I admire the Jewish lyceum, which was founded by our community. It is in the building of the former Jewish lyceum. It is a very good lyceum, which provides excellent education. Sometimes its students come to me to take a look at my pictures and illustrations of books. Many of them like to listen to the stories from the old days. They are good kids. It is a pity that the subjects are taught in Russian there and most of the kids do not know Estonian very well. They have to live in Estonia, continue their studies after lyceum and work. It will be hard without decent knowledge of Estonian.