Sheindlia Krishtal

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Inna Zlotnik

Sheindlia Krishtal lives in a two-room apartment in Kharkovskiy neighborhood in the outskirts of Kiev. She moved into this apartment with her husband in 1995. He husband died 6 years ago. Sheindlia is a short slim woman with a neat hairdo. She wears glasses. She is nice and kind. She likes to do things about the house. She cleans her apartment regularly regardless of her poor sight. She has a set of furniture of the 1960s: a cupboard, bookcase, sofa, table and chairs, two armchairs and a low table. She has a collection of Russian, Jewish and Ukrainian books. Evgenia edited many of these books by herself. Behind the glass in her cupboard she has portraits of her husband and sisters. Evgenia always helped people that had problems. Her former colleagues haven’t forgotten her: they call he regularly. Her nieces from Kiriat-Ono remember her and her nephew calls her from Boston. She receives food packages from Hesed. Her son lives in Kiev and supports her.

Family Background

My grandfather on my father’s side Shmuel Kryshtal was born in Ostrog, Western Ukraine, in 1850. My father told me that he was a tall, slim, dark-haired man. He was selling fabrics and haberdashery. I have never been in Ostrog, but I’ve read and heard that it is located on the banks of the Vilia and Goryn rivers. It was a district town in Volyn province, Russia. In the middle of ХIХ century Jews constituted half of population of Ostrog, and the rest of the population was Polish, Ukrainian, German, Lithuanian and Russian. This town was one of the biggest centers of the Jewish culture and trade in Volyn. The choral synagogue in Ostrog was a center of spiritual life. There was a cheder, yeshiva and a hospital at the main synagogue. There were few smaller synagogues. The Jewish theater and choir were popular with the local population. They also went on tours to the neighboring provinces.

My grandmother on my father’s side was also born in Ostrog. I don’t know her nee name – I only know that she was 7 years younger than my grandfather. My grandparents got married in the late 1870s – they had a traditional Jewish wedding with a huppah and there was also a rabbi at their wedding. They had a house of their own in Ostrog. I remember their photo where they were probably photographed at the beginning of ХХ century. My grandfather was a respectable gray-haired man with smiling eyes. He had a moustache and a small beard. He wore a dark suit and a black yarmulke on his head. My grandmother was a fat serious woman with thick fair hair wearing a dark dress. My grandmother was a housewife. My grandmother and grandfather were religious. They raised their children religious and my father and brother and grandparents often went to the synagogue together. The family observed Jewish traditions and celebrated holidays.

My father Gersh Kryshtal was born in 1878 He had a brother and few sisters. His brother Michael and sister Sonia were a little younger that my father. My father told me that his brother sang at the synagogue when he was a small boy and his sister was very handy – she could saw and knit. I don’t know anything about my father’s younger sisters. My father went to cheder when he was three. He enjoyed studying, but he didn’t continue his studies and after finishing cheder he began to assist his father with his trading business. My grandfather died in early 1900s and my grandmother died in 1920s. After my grandfather died my father moved to Zaslavl, near Ostrog in Volyn. [In 1910 the town was renamed to Iziaslav]. I don’t know for what reason they moved. In few years he opened a store there. In 1905 my father bought a two-storied house in the central square. I don’t know how he met my mother, but they got married in 1906. My mother told me that they had a Jewish wedding: there was a huppah in the yard of my mother parents’ home and there were kleizmers playing. There were many guests.

My mother Liya Gontar was born in 1887in Zaslavl – a small picturesque town near Ostrog in Volyn located in the hilly area. Jews constituted about half of population – there were about 300 hundred Jewish families. Jews were mostly involved in crafts and trade. There were few synagogues and cheder in the town. The majority of Jewish families lived in the central part of the town. The majority of population was Ukrainian – they were cattle breeders and lived in the outskirts of the town. There were also Polish families in the town. There were no conflicts between national communities – people got along well with one another and supported each other. A catholic cathedral, church and synagogues were very harmonious in the central square. Her father Israel Gontar was also born in Zaslavl in 1850s. I’ve seen him on a photograph. He was a big man with fair eyes, gray hair and a thick beard of average length. He wore a yarmulke. My mother told me that my grandfather was a tradesman, but I don’t know what exactly he did. My grandmother Rachel Gontar was born in a small town near Zaslavl in 1860s. I remember that she wore a kerchief, traditional for Jewish women. I also remember her kind smile. She lived in the family of her son Bencion, my mother’s older brother. It was also customary for Jews that parents lived with their sons’ families. My grandmother was religious – she lit candles on Friday evening and said a prayer over them. She only ate kosher food, celebrated all Jewish holidays and attended a synagogue.

My mother was the youngest daughter in the family. Her brother Bencion died when I was very young. I don’t know whether my grandmother had other children. I remember that Bencion had a wife and two daughters: Ida and Polia and two sons: Buzia and Shulim. Ida got married after the war. She lived in Ivano-Frankovsk. She has a daughter Raya: in 1970s they moved to Philadelphia, USA. Ida died in 1990s. We don’t correspond with Raya. Polia moved to Kiev in 1930s. She got married after the war and had two children: a daughter and a son – I don’t remember their names. In 1970s Polia and her children moved to Los-Angeles. She died in 1990s. Buzia, an older son, was wounded during the war. After the war he was shop superintendent at a plant in Kiev. He is a very nice man. His wife Dusia was an imperious woman. Their son Boria was born in 1950. He graduated from mechanic technical faculty of Moscow University. Dusia was a spoiled and jealous woman. She and Buzia got divorced. Buzia remarried and had another son – I don’t remember his name. Buzia, his 2nd wife and their son live in Haifa and Boria and his family lives in Jerusalem – he is a well-known scientist. Shulim and his family also live in Israel, but I don’t know anything about them.

My father and mother lived in the center of the town where they had a haberdashery store that occupied a part of their two-storied house. In 1908 their older daughter Fira was born. Before her there were stillborn twins. In 1911 my brother Samuel was born, in 1914 Faina, in 1916 Riva and I was born in 1922. The revolution of 1917 didn’t bring any changes into my parents’ life. Our family continued to live in a big house with a front and a backyard entrance. There was a big and fancy front door that led into a corridor, then to the kitchen with a big stove and to the backyard. There were lilac bushes (white, lilac and purple) in the yard and a nice orchard. We were a wealthy family. We had a housewife – Marta, a German woman. I remember her singing me German songs. I could understand German. My mother tongue is Yiddish, but we also spoke Russian and Ukrainian at home.

Growing Up

On the first floor we had 3 big rooms with high ceilings. Riva and I lived in one. We had carved wooden beds. There was also a desk and a wardrobe with carved doors. We also had a small corner where our dolls lived. Martha lived in another room. The biggest room was a living room with light flowered walls and goldish curtains on the windows. There was a light cupboard with fancy dishes in it and a long table with chairs around it upholstered with silk of the color of faded leaves. We had electricity. I also remember a big chandelier with three shades on the lamps. Samuel, Fira and Faina lived on the 2nd floor.

Our parents were religious: on Friday my mother lit a candle, my father said a prayer and the family sat down to a festive dinner. My mother made delicious kigeleh – “dumplings’ in Yiddish – from potatoes, flour or matsah. We also had chicken broth. On Saturday morning my parents went to the synagogue and when they returned the family had a rest: we read books – fiction on the most, had a festive dinner and sometimes my parents’ friends came to see us. On Saturday my father, my mother and Samuel went to the synagogue. We had an old Bible and Torah in Russian and in Hebrew with beautiful pictures. I enjoyed reading the Torah in Russian. I don’t remember going to the synagogue. There were few synagogues in Iziaslav - one of them was near my grandmother’s house in the old town where many Jewish families resided.

We celebrated all Jewish holidays at this table. I especially remember Pesach. One day before the holiday Martha took fancy dishes from the attic: plates with lovely patterns big plates with a blue pattern. I also remember a silver wine glass and other glasses. The house was thoroughly cleaned and any breadcrumbs were removed. On Seder my father put on his thales with wide black and yellow stripes and sat at the head of the table. My mother sat beside him and the children were sitting around the table. I enjoyed looking for matsah hid in the pillows to get it so that my father didn’t notice. We ate matsah, clear soup with kigeleh, Gefilte fish, forshmak [herring] and tsymes – stewed carrots or pumpkin with milk.

I joined Martha to go to the market in the center of the town. I remember women in white aprons selling dairy products. I was a small girl and didn’t ask which food was kosher and which was not, but I know for sure that at that time there were only kosher products at home. There was meat, fruit and berries sold at the market. On the bank of Goryn there was a Bernadine cathedral. It was a Polish neighborhood in Iziaslav.

In 1928 my grandmother Rachel died and my mother was grieving much after her. Shortly after my grandmother died our well being broke to pieces. We were ordered to move out of our house. I was only 7 years old and have only dim memories of the event. It happened in 1929 and now I understand that NKVD confiscated our house and store. We had never seen our father nervous before, but when it happened he became rather irritable. Martha disappeared all of a sudden. I couldn’t understand what was happening. We moved to the outskirts of the town. My father rented a small apartment of one room and kitchen. Our landlady – Basia Belous, a Jewish woman, was a dressmaker. She had two daughters: daughter Gusta and son Munia. They were a nice hardworking family. Gusta got married before the war and moved to Shepetovka, but in 1941 her family was killed by Germans. Our life changed dramatically since we moved. My mother baked bread by herself and we rode a horse-driven cart to buy food products in a village. My father didn’t have a job and we were constantly hungry. We dropped observing Jewish traditions or celebrating holiday. Authorities struggled against religion (1), and we were scared of these authorities – we didn’t quite know what to expect from them.

After we moved I fell ill with scarlet fever and we didn’t have any medications. My mother gave me warm water with milk. This has become my main medicine – if I get ill I have some warm water with milk. Scarlet fever resulted in problems with kidneys that I’ve suffered from ever since.

My mother had a stroke and was confined to bed when she was only a little over 40. Riva and I stayed with our parents – the other children moved to other locations. Riva and I were responsible for housekeeping. Riva used to say: “O’K – I will knit you a hat and you wash the floor." Faina became a schoolteacher in a school near Iziaslav when she was 16. Fira finished an accounting school and worked as accountant at the Wapniarka station – office of Odessa railroad.

My brother Samuel and his friend Motia Precizen went to work at the Crimean metallurgical plant in 1928. My brother studied at the Railroad College by correspondence. He graduated and went to work at the railroad shops near protection of the Virgin nunnery in Kiev. He rented a room in 15, Pokrovskogo Street in the center of the city. He must have told his Jewish landlords about his life and that his mother was very ill. There were more medical opportunities in Kiev and my father, Samuel and sisters decided to move to Kiev.

There was an annex in the yard of the house where Samuel lived. He refurbished it and our family moved in there from Iziaslav. This happened in 1933 during famine (2), and the situation was more favorable in Kiev. For us a piece of bread and a glass of milk was royal food. Of course, the situation was very tough, but I can’t remember that we were starving, but people in villages were starving to death.

In 1929 I went to Ukrainian secondary school. There were small classrooms at school and many pupils. The school was far away and in winter younger children were taken by older ones on sleighs. We learned to read and write in Ukrainian at school. After the war I met with my classmates in Chernovtsy. In the second form I became a pioneer, but I don’t remember any involvement in the pioneer activities. There were quite a few Jewish children in our class, but there was no anti-Semitism. I studied 4 years at this school.

My father constructed another room to our room, but we still didn’t have enough space. Our father was very hardworking. I remember going to a village near Kiev with him. He was purchasing leather for leather industry. Shortly after we moved to Kiev my mother had another stroke and again she had to stay in bed. At that time Fira divorced her husband came back from Wapniarka to take care of her mother. Faina resided in a very small room in a communal apartment in Luteranskaya Street in the center. Soon my brother married a Jewish woman, her name was written as Ginda in her passport, but she was commonly called Donia. He moved to his wife in Smirnov-Lastochkin Street. Samuel studied in Kiev Industrial Institute by correspondence. He began to work there as a worker and reached a position of superintendent at the Mechanic plant. Faina entered Financial Economic Institute. She studied well and got a job at the Ministry of Finance. She often went on business trips to Rovno. Riva entered Chemical technological Institute – she studied and worked as a pioneer leader at school in Artyom Street. Riva married Motia Precizen, Samuel’s friend - he finished military college. He had a room in the building for military on the corner of Proreznaya and Kreschatik. Before the war Motia was sent to Peremyshl and Riva had to give up her studies at the Institute and go to Peremyshl.

I went to the fifth form at school #21. It was a Ukrainian school. It was an old and beautiful building with high halls and big windows. Later our school moved to another building in Chekhov Lane. I was fond of languages and liked Russian and Ukrainian classes. Our class tutor Maya Afanasievna was a very nice woman. Later she went to work in a different school in Artyom Street. I always protected the weak ones in my class. My classmate Lilia was a not quite fond of studying. Once she failed at an exam. Other children that were not quite strong were more resourceful, including my friend Fania Wolfman, and managed at the exam. Our class had a meeting where Lilia was reprimanded for her poor performance. I couldn’t stand injustice and spoke at the meeting telling them the truth. Fania was angry with me, but later she forgave me. Later, when I worked at the editor’s house, I helped many people that asked me for help. My other close friend beside Fania was Nadia Belan. We were friends after the war, too. There were Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish children in my class – we got along very well and never cared about national origins. I spent my summer vacations in town – we went to the river to swim or walked in parks. We were poor and my parents couldn’t afford to pay for my vacations elsewhere. I never left home before 1941.

In 1938 when I turned 16 I received a passport. I was commonly called Zhenia, and at home I was seldom called Sheindlia. I decided to keep my Jewish name in the passport and I am very proud of it.

My mother was ill and we took her to sanatorium 4 and to the railroad hospital, but in vain. She died in 1938 and was buried at Lukianovskoye Jewish cemetery.

In 1939 I finished school and decided to enter philology faculty in Kiev University. My classmates Alla Fisenko and Fania Wolfman also went to University. They finished school with honors and were in a privileged position, but I firmly decided for myself that I would fight for getting there. I passed all exams successfully and entered the philology faculty of Kiev University. My Jewish classmates also entered higher educational institutions. There was no national segregation at that time.

When I was a 2nd year student we were trained to be medical nurses. The war was in the air. We didn’t believe that Hitler could attack the Soviet Union. Newspapers and radio programs were convincing us that this could not happen.

During the War

When the war began on 22 June 1941 (3) students went to excavate trenches in the vicinity of Kiev. Soon evacuation was announced at the plant where my brother worked. My father, Fira, Faina and I evacuated with Samuel’s family to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan [about 4 thousand km from Kiev]. Our trip lasted for about two months. We went on freight train that was continuously bombed on the way. We went through Kuibyshev where Riva and her 6-months old daughter had to stop. Lilia got ill from exhaustion and had to stay in hospital for 6 months. Faina stayed in Kuibyshev with Riva to look after Lilia and Samuel, my father ad Fira went to Alma-Ata.

I went to study in the university in Alma-Ata I wanted to continue studies at the faculty of philology. As for university, there was a university in each republic with a number of different faculties. During my studies I lived in the hostel in Alma-Ata-2 – that was the center of the town and Alma-Ata-1 was in the outskirts of the city. My father and Fira lived in Alma-Ata-1 (the city of Alma-Ata was administratively divided into two parts: Alma-Ata-1 and Alma-Ata-2). On weekends I walked 7 km to visit my relatives. Fira worked at the accounting office of the railroad and my father was her assistant. In half a year Faina, Riva and Lilia came from Kuibyshev. Fira found a job at the Ministry of Finance. She got a room at a hostel not far from the hostel where I lived. Riva went to work at a kindergarten. She received letters from her husband – she knew that he was in a tank division at the front. His tank was burning once, but he survived. Samuel, Donia and Israel lived separately and we didn’t keep in touch with them. Our Kiev University was evacuated to Kzyl-Orda in Kazakhstan. Lecturers from Moscow and Leningrad Universities were also in evacuation and taught at my University. I decided not to go to Kzyl-Orda, as there was a very high level of teaching at our University. There were students from all corners of the Soviet Union in our hostel: Rumania, Ukraine and Russia. We were young and didn’t focus on hardships – we were not starving and that was all right. We made soup with flour and water that we called zatirukha. We had meals at the canteen. I took an active part in public activities. I always went to Komsomol meetings and was a political officer in our troops that were sent to do agricultural work.

I studied and worked at the radio committee in Alma-Ata and wrote about the situation at the front about Polish, Russian, Jewish and Ukrainian soldiers and their heroic struggle against fascist occupants.

In 1944 I finished the university in Alma-Ata and continued my work at the radio committee until reevacuation was announced in 1945. How happy we were to come back home. There were fireworks on Victory Day of 9 May 1945 – people came out into the streets greeting each other on victory, crying and laughing. We: my father and I, Fira, Faina, Riva, Lilia and Samuel with his family returned to Kiev by train via Moscow. The trip lasted 7 days. I went to the radio committee in Moscow and hoped to obtain a job assignment to Kiev, but they suggested that I addressed the radio agency in Kiev.

After the War

Our house was destroyed. My father found a small room in a basement in 9, Vorovskogo Street. It was an awful dwelling, but we were glad to have a roof over our heads. Riva’s house was ruined during the war and Riva, her husband and Lilia moved to Germany and later – to the border with China in the Far East. Their second daughter Natasha was born there. Fira and Faina lived in Kiev after the war, but their personal life left much to be desired. Fira lived in Riva’s family for some time. She didn’t remarry. Faina gave birth to a daughter – Bella in 1954. Samuel, Donia and Israel also returned to Kiev and settled down in their previous apartment in Smirnov-Lastochkin Street. After the war their daughter Elizabeth was born. We call her Lialia. She was named after her grandmother – our mother’s name was Liya.

I went to the radio committee – I thought I was a good journalist and my materials were valued highly in Moscow radio agency. However, it was difficult for a Jew to get an employment – I was rejected. I addressed this issue to the Communist party Central Committee – how naïve I was thinking that they might help. I heard that the Regional Police agency was looking for a teacher of the Russian language. I submitted my documents and in some time they sent me their request to visit them regarding my employment issue. I became a Russian teacher and, as it usually happens I also had a job offer from a popular Ukrainian newspaper ‘Youth of Ukraine”. I began to work in newspaper.

There was little food after the war, but we were young and took it easy. In 1947 we received food coupons and rationed food, but it was all right with us.

I went on business trips as correspondent and then I got an offer to go to Chernovtsy as correspondent [400 km from Kiev]. I made tours of Stanislavskaya and Chernovitskaya region. There were Jews in these villages and I didn’t face any anti-Semitism. I lived in a rabbi’s house in Chernovtsy. He was in the ghetto during the Holocaust with his wife and daughter. They had to go through terrible hardships, but they survived. I lived in the room that formerly belonged to the rabbi’s family and they were not happy to have another tenant. The rabbi was a short man wearing a yarmulke, his wife was a short woman, too. The synagogue was closed and they constantly prayed at home. I viewed them as vestige of the past. I met with Tania – my former roommate in Alma-Ata. She lived nearby. She knew the rabbi’s family and told them that they didn’t have to fear anything and that I was a Jew – how happy they were. They began to treat me in a different way. I had a telephone installed in my room and got an opportunity to transmit my materials to editor’s office in Kiev.

I didn’t stay in Kiev long. I replaced Irina Shkarovskaya, head of the department of studying young people. Irina got a new job at the “Barvinok” magazine in Kiev and recommended me to her former position. This position had to be approved by the Komsomol Central Committee. I was a Komsomol leader and had a good reputation. I was approved and began head of the department: I wrote about schools and higher educational institutions.

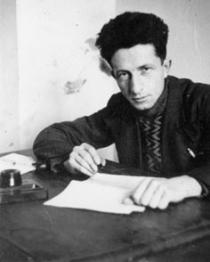

At the end of 1947 Shabsai Khandros, (he was generally called Sasha) returned from the construction of automobile factory. He became head of the department of propaganda in the “Youth of Ukraine” newspaper. I transmitted my materials to him by phone. This was how we met. We had food coupons and went together to have meals at the canteen in 22, Vorovskogo Street. He began to court me – he brought me a little food to the train when I was going on business one day. Or he would put an orange into my desk when oranges where hard to get. Sasha was a taciturn man and when he said something it was interesting and smart. We began to date and built up very warm relationships.

In 1948 our father died at the age of 69. We buried him near the Babiy Yar in Lukiyanovskoye cemetery (4). In 1980s authorities planned to build a TV center at the area where the cemetery was located and some people moved their ancestors’ graves to the Jewish corner (area 49) on Baikovoye cemetery, the central cemetery in Kiev. While my father was alive we tried to stick to the Jewish traditions: we celebrated Pesach and my father fasted at Yom Kippur, but after he died we lead a life like any other ordinary Soviet family.

In 1949 Sasha got a problem during his night shift at the printing house - the central committee of the Communist party discovered a typo in the newspaper. This happened during the period of struggle against cosmopolitism (5) and the Central Committee insisted that he was dismissed. He was deeply upset about it and we all felt sorry for him, but his boss couldn’t help him, because they got instructions from higher authorities. Sasha was a war veteran and had an order of the Great patriotic War and few medals. He wrote letters to all newspapers looking for justice and even the “Komsomol Truth”, a most popular newspaper in the former USSR, published his letter, but there was nothing to do. His editor valued him high and gave him a job assignment in Donbass. He lived there at the hotel and we corresponded for whole year. Later our editor Mr. Statipko was promoted and replaced by Mr. Kolomiets, a former secretary for propaganda of the Chernovtsy regional Party committee. We worked together in Western Ukraine and developed nice relationships. Kolomiets was aware that Sasha and I were close and assured me that he would help. He helped to return Khandros to the propaganda department in Kiev, only Sasha couldn’t be restored on his former position.

Our deputy editor kept telling me to join the party and said that he would give his recommendation. But during the period of struggle against cosmopolitism he changed his attitude dramatically. Once I joined a group of representatives of the Central Committee of Komsomol of Ukraine (headed by 2nd secretary Semichastniy) going to Stanislav region to monitor how they managed with their work with young people. Zaslavskiy, our former deputy editor, asked me to take a letter to director of Stanislav garment factory: during the war Zaslavskiy, his wife and director of the factory were frontline friends. I called this woman when we arrived to tell her that I had a letter for her. She said that she would be happy to see me, only she couldn’t invite me home, because it was so cold in her house and there were no utilities functioning. We decided to meet at a restaurant, she ordered schnitzel and coffee and I gave her the letter. On the following day I came to the café where our group was having dinner and said “hallo” to Semichastniy. He smiled and said “Well, well, we’ve come here to criticize director of the factory and you, a Komsomol secretary and a journalist, meet with him at the restaurant?” - these people had their informers everywhere. I went to see him in his office later to explain that a frontline friends of director of the factory asked me to give them a letter. He smiled and said “Well, I understand, but you know how wicked ideas people can have”. When I returned to Kiev deputy editor that was also secretary of the Party organization asked me in his office and said “Here we criticize director of the factory for his failure to organize work with young people and our correspondent enjoys herself in a restaurant with them!” This happened during the period of struggle against cosmopolitism and my boss could accuse me of “slackening of political awareness”, but fortunately, it didn’t happen. Semichastniy was a decent man and didn’t pay attention to this event.

After Sasha returned to Kiev in 1949 we got married. Since we were both journalists I decided against changing my last name to my husband’s and remained Krishtal. After the civil ceremony our colleagues arranged a wedding party for us in the office. They bought a bottle of champaign and changed the sign “Champaign” to Komsomol youth wedding #1” and also glued our photos on the label. They also gave us a beautiful set of dishes made in Czechoslovakia – I still have 3 pieces from it. So, we celebrated our Komsomol youth wedding in our basement in Vorovskogo Street.

My husband Shabsai Khandros was born in Kiev in 1913. Due to residential restrictions the Khandros family lived in Demeevka, a neighborhood in the vicinity of Kiev (6). Sasha’s great grandfather served in the tsarist army for 25 years – he was a cantonist (7). Cantonists were often forced to convert to Christianity, but his great grandfather didn’t do it. They were a purely Jewish family. Sasha’s parents lived in two small rooms in a one-storied building. His father Joseph Khandros died in evacuation during the Great patriotic war. I don’t know what he did for a living. His mother’s name was Rachel. Sasha’s older sister Sonia lived in Moscow. Her husband was editor of a military newspaper before the war. He went to the front when the Great Patriotic war began and perished at the front in Byelorussia. His parents were revolutionaries; they lived in Russia and held high official posts. During the war Sonia and her daughter Ira were in evacuation in Siberia and after the war her deceased husband's family helped her to get a job at a plant in Moscow. She worked at technical; archives department. She was a very smart woman.

My husband worked at a shoe factory in Kiev before the war. He was a smart man and often wrote articles about the life of workers. He sent them to newspapers. He was noticed and employed by “Komsomolets of Ukraine” newspaper after the war this newspaper was renamed to “Youth of Ukraine”[a big all-Ukrainian weekly newspaper]. Before the war Sasha studied at the philology faculty in Kiev University. He was at the front during the war and became a Party member in the army.

After the wedding we didn’t have a place to live. Sasha lived with his mother in two rooms that they were renting, his younger sister Zhenia lived in another room with her husband Zhenia and son Lyonia. I moved to my husband and we settled down in a small room. Sasha needed a desk to write. He bought a desk that occupied three fourths of our room. We also had a narrow steel bed. We didn’t observe any Jewish traditions. It wasn’t popular to lead a religious way of life and religiosity was persecuted. Our landlady leased apartments in the house where we lived to Jewish families, so we had Jewish neighbors.

This was the period of persecution of Jews, but we couldn’t speak our mind, even though we understood that there was much injustice. I would like to tell you the story of journalist Shmushkevich that worked for the “Stalin’s kinship” newspaper before the war. During the war he was in captivity, but he managed to escape and struggled in the French resistance Movement. When he returned to his home country Soviet authorities put him in jail and we didn’t hear from him for a longtime.

On 5 March 1953 Stalin died and there was mourning declared all over the country. People had to wear black armbands, there were meetings and many people were crying. There was terrible uncertainty about what was going to happen. Many people believed Stalin, but there were those, including Sasha and I that doubted his impeccability remembering 1937, cosmopolitism and “doctors” case (9). After Stalin died the period of rehabilitation began and Smushkevich returned in two years’ time. People looked at him as at an enemy. Only after the closed ХХth Party Congress (9) in 1956 the Party decisions were announced at closed party meetings. The cult of Stalin was denounced, but it was still not safe to speak about it openly. Sasha was a member of the Party and told me confidentially about the situation.

In 1954 our son Yura was born. We had no comforts: no gas or running water. My sister Faina managed to exchange our room in the basement to a 12-square-meter room on the corner of Saksaganskogo and Tarasovskaya Street, one of central neighborhoods in Kiev [central districts of towns are more prestigious to live at due to more extensive infrastructure, public transportation, closeness to work.]. Later she received a room in a communal apartment in Kirov Street and we could have her room in Saksaganskogo Street at our disposal. Our neighbors were the family of Dunayevskiye – very nice people. The father of the family worked at the railroad department. His wife was paralyzed and he looked after her, but their son was a rascal. The Dunaevskiy family lived in a bigger room with a balcony and we resided in a smaller room. There was another Jewish family in this apartment. We got along well with our neighbors except for the son of Dunayevskiy. He treated his parents badly and I could hardly stand injustice, as usual.

Young journalists came to work in our newspaper. They were very young that had a long road ahead of them to accumulate some experience, but they brought in national rows that I couldn’t live in piece with. Our editor was anti-Semite and wished to get rid of me. I complained to the Central Committee of Komsomol – they knew me and I needed their protection. I stayed at work, but I lost my position of head of department. A University graduate held my position, but I had to do all work by myself. We hired a baby sitter for our son – a very nice woman, but she quit. We hired another one, but she wasn’t quite suitable and we decided that it was better for me to quit work and stay at home. My husband kept his job, because he was a veteran of the war and had worked in this newspaper for many years. I became a part-time correspondent in 1955 for the “Socialist culture” and “Pravda” newspapers.

The Central Committee of the Party founded the “Rabochaya Gazette” and Sasha was recommended to this newspaper as one of the best journalists. His colleague Elena Riabukha said to me once: “You know how people call your husband? They call him tsadik – he is so very special”. This is exactly what Sasha was like: smart, intelligent and decent. The “Rabochaya Gazette” became a trade union organ and they began to build a house for their employees in Vinnitskaya Street. In 1962 we received a two-room apartment on the 1st floor in this home. We were so happy to have an apartment of our own – and the neighborhood was very nice, quiet, green and located near the center of the city.

I worked part-time for almost 9 years. It was convenient – my husband often went on business trips and I stayed at home to look after our son. I used to write at night. When our son went to the 2nd form at school I went to work for “Sviatoshinskaya Gazette”: I was a corrector, editor, correspondent and I also went on business trips. Our friends visited us sometimes – we had tea and various discussions. We didn’t celebrate Soviet holidays – we usually worked on these days, and, besides, they weren’t so important for my husband and me. My husband and I went to theaters, cinema and read foreign and Russian classical books.

Yura was a smart and nice boy. He studied at Ukrainian school #115. Yura was fond of mathematic. After finishing the 8th form he heard about admission to school #145 with deeper study of mathematic and physics. This school was within the structure of Kiev State University. Their teachers were at the same time lecturers in the University and best pupils were admitted to the university without exams after finishing school. He didn’t tell us a word, went there and passed entrance exams. He was admitted to school. He took part in various mathematical contests and once took the first place in Olympiad of Moscow University. He got an official invitation to study at the University. In 1971 Yura finished school and submitted his documents to Mechanical Physical Faculty of Moscow University. He knew that it was hard to get there without bribes or acquaintances, but he went to take exams. We didn’t have any money to bribe people and we didn’t have any acquaintances. Yura failed to enter Moscow University and submitted his documents to Kiev University. He got a “four” in mathematic, although he gave correct answers. I went to the dean of the faculty and demanded that they founded a commission. The commission checked his test – it was correct. The dean told me to take it easy since it didn’t matter much whether he got a “four” or “five”. But Yura was admitted as an evening student. It meant that he was subject to mobilization to the army after the first year. The dean promised me to transfer Yura to the daytime course after the first year. But what happened was that he transferred another student to the daytime course and I decided to talk to the rector. I didn’t tell Yura about my plans – he had a strong character and might not allow me to go. I talked to the rector – no results. I lost me temper and called him an anti-Semite. He said he was going to call the police. “Yes, call the police – I am staying here, but you do not transfer my son, because he is a Jew”. He didn’t call the police, but he didn’t transfer my son to the daytime course either.

Yura served in the Navy in Severomorsk. He has been in the North Pole.

I worked as editor at the technical information department of the Ministry of timber and logging industry in Kreschatik. I went on tours to all forestries in Ukraine, including the Carpathian Mountains. When I was about 50 I fainted at a meeting and was sent to neurological clinic. My eyesight became worse. I became an invalid of the third category. At 51 I was classified as an invalid of the 2nd category and it gave me the right to retie before term. When my condition improved I continued to write as part-time correspondent and worked at the Ukrainian Association of blind people. I worked 39 years in total.

Yura returned home in 3 years. He matured in the army.

Yura studied at the University and worked at the design office of the Ministry of Agriculture. He met a candidate of seines from the Institute of cybernetics. He told a doctor of sciences from this Institute about Yura. This doctor of sciences invited Yura to work at the Institute. Yura met his future wife Luda there. She is Ukrainian and had a son before she met Yura. Yura doesn’t have any children. Of course, I wanted him to marry a Jewish woman. And have children of his own, but it turned out differently. Luda is a nice woman and they live well and this is most important for me.

In 1978 my brother Samuel’s son moved to Boston, USA. Samuel’s daughter Lialia married a Russian man. She has a son – Alyosha, but she divorced her husband. Samuel passed away in 1980 – he was a very intelligent and responsible man. We buried him in the Jewish corner in Berkovtsy cemetery. Lialia moved to Israel shortly afterward and his wife Donia lives in Kiev with her elderly mother.

My sister Faina’s daughter Bella was ill with asthma and they moved to Israel in 1991 to have an opportunity to give Bella a proper treatment. Riva’s daughter Lilia moved to Israel from Petrovo-Dalnee in Podmoscoviye where she worked as children’s doctor. Her husband Yulik worked at the construction of a big power plant and when it was completed they moved to Israel. Lilia has fluent Hebrew and works as a doctor at a trade school. Lilia observes Jewish traditions: she lights candles on Friday and attends a synagogue. Her son Zhenia turned 32. He graduated from the Polytechnic Institute in Haifa and works in the Navy. He is a tall and handsome young man. He is single.

In 1995 my husband and I received a two-room apartment in Kharkovskiy neighborhood in the outskirts of Kiev. My son and his family live in our old apartment. We were so happy to get this apartment, but Sasha didn’t long afterward – he passed away in 1996. We buried him at Lesnoy cemetery - there are no Jewish corners there. Fira died one year later. She was buried at Jewish corner near her parents' grave.

In 1996 I visited Israel. I enjoyed my stay there and admired the beauty of the country, but I never thought of leaving Kiev - my home, my friends and my job. I met with my relatives – they are well settled. I am happy for Faina – Bella likes it there. They live in Kiriat-Ono near Tel-Aviv. I saw Faina for the last time – she passed away 4 years ago.

My sister Riva died in 1999- she was buried in Chernovtsy.

I am very happy that my son lives in Kiev and often comes to see me. Lilia and Bella call from Israel. I often call my former colleagues, but I feel lonely in this place without my husband. It is hard for me to go outside. I receive packaged food every month from Hesed. They arrange lectures and concerts in Hesed, but I can’t go there by bus – I get sick. Many Jews of my age have come back to the Jewish culture: they attend synagogues and celebrate Jewish holidays. I take an interest in the Jewish culture and history, but I don’t go to the synagogue; my husband and I didn’t attend synagogues, as it was difficult for us to change our attitudes.

I receive 59 hrivna of pension and my son supports me. I like to do the house myself. My friends visit me every now and then and we discuss the latest news. Life goes on.

Glossary: