Semyon Tilipman

Odessa

Ukraine

Interviewer: Natalia Fomina

Date of interview: October, 2003

Semyon Moiseevich Tilipman, his wife Tatiana and their younger son Evgeni live in a four-room apartment in a new district of Odessa. Semyon Moiseevich has kept his military bearing. He is tall and slender man with thinning gray hair on his forehead. Semyon Moiseevich can hardly speak considering his age of 87. Semyon’s wife Tatiana Israilevna is little, nice and lively women of 83. Semyon Moiseevich often made interval while speaking, but Tatiana Israilevna helped her husband every now and then mentioning details of the family history that she remembered well. In one room there is a small sofa covered with a plaid and a nice Chinese carpet on the wall. The living room is big and bright. It’s beautifully furnished with the furniture pieces that they bought in the 1970s. There is a dinner set of Meisen china in the cupboard, old bronze candle stands on the TV set and few portraits of Tatiana Israilevna and Semyon Moiseevich on the walls.

My paternal grandfather Shymon Tilipman was living in Dzygovka town, Vinnitsa region. [Dzygovka is a town in Yampol district, Podolsk province, in 1897 its population was 7,194 residents and 2,187 of them were Jews.] I have very little information about him. I don’t know where he was born or what he did for a living. I was named Shymon after my grandfather. I was born in 1916 and since Jews traditionally name their children after their deceased relatives I guess my grandfather must have passed away before. I was the third son in the family. My older brother Boris was born in 1911, I believe my grandfather died some time at this period. I don’t know anything about my grandmother. My wife Tatiana grew up in Dzygovka where people knew each other, and she thinks my grandfather Shymon Tilipman was a melamed. I am sure my grandfather and grandmother were religious. My father was raised religious. I know about my grandparents’ four children. They were born in Dzygovka.

My father’s older brother Leib was born in the late 1880s. My wife says he was a Yiddish teacher in the Jewish school in the village. She knew him. I only saw him once in the early 1930s when uncle Leib came to Odessa to exchange some foreign money to rubles. He didn’t mention to my father the purpose of his visit. He probably didn’t want my father to know that he was receiving money from abroad. I think my father had one more brother who moved abroad and uncle Leib received money from him. Private currency exchange agents in Odessa cheated him. They took his currency and gave him a ‘doll’ [a pile of paper sheets with banknotes on the top and at the bottom of a pile]. Since this operation was illegal there was nobody he could complain to and uncle Leib went back home with nothing for his pain. Uncle Leib died Dzygovka in the early 1930s. He had three children: two sons and a daughter. His daughter Basia visited Odessa in 1936 and my future wife took her around the town. After the Great Patriotic War 1 my wife and I received an invitation to Basia daughter’s wedding, but we failed to go there because our children were too little then. We didn’t keep any contacts with them and have no information about them.

My father’s brother Meir Tilipman lived in Odessa. I think he was born in the late 1890s. Meir was ill with tuberculosis since his childhood. He didn’t have a profession. Meir’s wife was some distant relative and belonged to the Tilipman kinship. She died long before the Great Patriotic War. They had two sons: Shymon and Yania. Shymon, the older one, was born in Odessa in 1923. My parents kept in touch and supported them. Meir and his son stayed in Odessa during occupation. They perished. Shymon was at the front. He demobilized in 1947 and returned to Odessa. He got married. His wife Tsylia was a Jew. I attended his son Edik circumcision ritual. Edik was born in 1948. The ritual took place in their home and they invited the only mohel in Odessa Mr Biebergal. Somebody from the community assisted him. Few years after the army Shymon was a sailor and worked for a whaling association called Antarctic. Shymon told me that when his boat harbored in the ports abroad he spoke Yiddish to local Jews that Soviet sailors were forbidden to do. They were allowed to land in groups of three so that one of them kept an eye on the others and reported to his management. So someone reported on Shymon and he was fired. After dismissal Shymon was a tailor and then worked at the machine building plant in Odessa. Shymon’s son Edik tried to enter a college in Odessa several times. He failed at exams for something ridiculous like a wrong description of a subject in his composition. He finished a college in Irkutsk, [in Russia] in the end. Shymon was a talented and hardworking man. He studied English on his own. In the 1970s Shymon and Tsylia moved to USA. They live in New Jersey. We correspond with them. Edik lives in Israel.

My father Moisey Tilipman was born in Dzygovka town some time in the 1890s. My father was raised religious. I think he studied in cheder. Father spoke Yiddish and prayed in Hebrew. He met my mother in the town when he was in his teens.

My mother’s parents came from Soroki town [a district town in Bessarabia province, today in Moldavia; according to census of 1897 there were 15,351 residents and 8,783 of them were Jews. In 1910 there was a synagogue and 16 prayer houses in Soroki] in Bessarabia 2. All I know about my maternal grandfather is that his name was Naum Davidovich. Before 1940 Soroki belonged to Romania and we didn’t have any contact with my mother’s relatives. In the 1950s I visited Soroki in search of my mother’s family, but I didn’t find anyone. I don’t even know the name of my maternal grandmother.

I remember my mother’s brother Moisha Davidovich residing in Odessa. His wife’s name was Riva. They had two children: son Naum and daughter Rosa. They were born in Odessa. I guess, Moisha moved to Odessa before the October Revolution 3. I know that he delivered bread to customers of a bakery in Odessa. During the famine [in Ukraine] 4 in 1932-1933 he supported our family. He perished along with my parents. He and both of them were convinced that there was nothing to fear about Germans. They even convinced other Jews to stay in their homes. Riva and her children were in evacuation and survived. Aunt Riva died in the 1950s. Rosa moved to the USA in the 1970s and we lost contact with her. Naum finished the Jewish college called Euromol on the corner of Kanatnaya and Kirov Streets. He was a sociable young man and was fond of photography. After finishing his College he worked at the plant named after Lenin. He managed to arrange for evacuation of his mother and sister with other employees of his plant to Sverdlovsk. From there he went to the army and was demobilized after he was wounded at the front. He returned to Sverdlovsk and worked as chief engineer of the machine building plant. Naum spent his vacation in Odessa every year. He died six years ago, in 1998.

My mother Hana Davidovich was born in Soroki in late 1890s. At the age of 14 she came to Dzygovka located on the opposite bank of the Dnestr River to study sewing. She met my father there. My father’s parents were against their marriage. They were probably a wealthier family than my mother's. My parents moved to Odessa secretly in the late 1900s. They had a traditional Jewish wedding in Odessa. My grandfather didn’t forgive my father. He didn’t have any contacts with father. My parents never visited Dzygovka from what I remember. Our father loved our mother dearly and respected her. He believed and so do I that a woman is the head of a family. She needs to be cared for and get everything best. My mother was a Greek type: she had swarthy skin, big black eyes and thick hair. She was nice and kind like all mothers are.

In 1911 my parents had their older son born. It seems they named him Boris. In 1913 another boy was born whose name I can’t remember. I was born in 1916. I was born on the last day of Pesach, but since it is observed on different dates of the European calendar I wrote it in my documents as 22 April – Lenin’s birthday 5. I was named Shymon after my paternal grandfather. Later I changed the name Shymon to Semyon for my sons’ sake. [Editor’s note: Semyon wanted his sons to have a patronymic that sounded more familiar to Russians.] When I was born we were living in a basement apartment in Malorossiyskaya Street, Lazarev Street at present. As far as I remember there were 8 steps downstairs to our apartment. I still have a scar on my finger on the right hand I had squeezed with the door to the basement when I was about 5 years old. There were two rooms in the apartment, I believe. There was no kitchen, but we had a kerosene stove and a table in the corner of the room. In 1921 during the famine in Odessa my older brothers starved to death. They were buried on the same day at Jewish cemetery. At that time an apartment on the first floor was vacated and we moved there. It was bigger than our previous apartment. I remember that the front door opened into some kind of a kitchen. I remember my mother cutting bread into small pieces and my older brother always watching her. He never had enough food and was always hungry. I don’t remember any furniture. I remember that a window faced the yard and there was sufficient light in the apartment. My father’s brother Meir moved into our former apartment in the basement.

My mother didn’t work. My father was a vendor at the Alexeevski market. He had a small booth shop at the market selling something. According to gradations of Soviet authorities he was a ‘non-working element’ [a term that determined businessmen in the former USSR at that period]. I went to school at the age of six in 1922. There were specific schools where I could be admitted as a son of a ‘non-working element’. There was a big higher secondary school in Komsomolskaya Street where they didn’t admit me. I went to lower secondary school #64 in Vneshniaya Street. I remember director of my school Vasili Ivanovich. He was our teacher of mathematics. I was good at mathematics. My favorite subjects were arithmetic, geometry and algebra. I also remember our art teacher. Her patronymic was Petrovna and we blandly teased her calling her 'Petrushka'. I don’t even remember whether I ever became a pioneer at school. At that period we lived in a new apartment in Maloarnautskaya Street where there was a pioneer fore post that was sort of a pioneer club. I remember that Stoliarskiy students often performed there. [Editor’s note: Pyotr Solomonovich Stolarskiy, 1871–1944, was a Soviet violinist and pedagog. One of the founders of the Soviet violin school. He developed a new method of teaching to play the violin. In 1933 he organized the first 10-year music school that was given his name.] Many of his pupils became famous musicians. There were other educational activities in this pioneer club. I also remember the cinema theater named after Trotskiy 6 behind the corner in Preobrazhenskogo Street. There was an inn nearby where farmers who brought their food products to sell at Privoz [the biggest market in Odessa] stayed. There was a big yard where about two dozens wagons could park where they had a big screen to show movies. We sneaked in there across the roof of a neighboring house.

In 1923 my brother Fima was born. In 1924 my sister Ghenia was born. They were both born in the apartment on the second floor of a two-storied wing in the yard in 84, Arnautskaya Street. There was running water in this apartment, but the toilet was in the yard. There was a hallway, a small kitchen and a big room in this apartment. In the early 1930s we had a kerosene lamp hanging in the center of the ceiling. This room was my parents and my sister’s bedroom. I slept in the hallway. As for Fima, I guess he slept in the kitchen. Our neighbors were Jews, the family of Kapels. I remember when Ghenia was born. There is a Jewish traditional celebration of birth with lekakh mit bronfn [honey cake with vodka in Yiddish]. My mother made delicious lekakh. Our neighbors – the Kapel family – uncle Moisha and aunt Riva and Meir came to celebrate. Ghenia was a long waited girl in the family. I also remember something else. Once our parents went to the theater and we, kids, were at home. We put Ghenia to bed – and she slept with our mother. Ghenia was about five years old. The wing of the house where we lived was old. A mouse or even a rat got into the bed and bit Ghenia on her temple. Fima and I chased after it but gave up when it got between our wardrobe and the wall. A day later it was discovered in a small drawer in the samovar table where we kept spoons and forks. Ghenia had injections against rabies made, but everything turned out to be all right and she didn’t even have a scar afterward.

My parents were religious. On holidays they went to the synagogue on the corner of Staroportofrankovskaya and Novorybnaya Streets. This synagogue was ruined during the Great Patriotic War. There were few other synagogues in Odessa. I attended the synagogue with my parents when I was 10-12 years old, but I don’t remember any details. I remember that my father liked listening to a good cantor. My parents spoke Yiddish and I could understand Yiddish well. They observed Sabbath. I remember my mother lighting candles. I don’t know whether my father worked on Saturday. I just don’t remember. I didn’t care. My mother made Gefilte fish and matzah dishes at Pesach: pudding and pancakes. My father and I liked goose fat cracklings. My mother put a bowl of cracklings on the table for us to ‘satisfy our eyes’ hunger’. I remember what she said: ‘When you want to give someone food to eat to his heart’s content give him a lot of food and his appetite would be half less’. I also remember Chanukkah and dreidel and we got Chanukkah gelt. My mother went to buy food at the Privoz: fish, poultry, vegetables and fruit. I also remember that mother bought live chickens and took them to a shochet. There was a shochet at Privoz for a long time after the Great Patriotic War.

My father had to fight to make his living. He was a vendor, but he didn’t quite like it and in the 1920s he went to work as a binder at the ‘Chermorskaya Communa’ publishing office. Since his salary was not enough to support the family, he additionally made elastic bands, leather wristlets and shoelaces. Actually such small craftsmen preferred to unite into teams to be able to purchase necessary equipment and materials. My father treated leather in the attic. I helped my father as much as I could with operating his weaving equipment or, wristlet and elastic band making units. Or I fixed shoelace tips with a special device. I don’t remember how these goods were sold, I guess there was someone whom I didn’t know.

I remember the Lerner family. I believe the head of the family was my father’s companion. They lived in #28, Komsomolskaya Street. I remember that they visited us and we visited them. I remember that my parents’ closest friends were the Pavlovskiye, a Jewish family. Their son Izia was about the same age with me. Izia had twins born in 1947: Leonid and Alexandr. They finished VGIK [All-Union State College of Cinematography in Moscow]. Alexandr became a popular cinema producer. Izia Pavlovski’s father was a tailor. (When we returned to Odessa after the Great Patriotic War he made clothes for our children. I remember that he altered my uniform overcoat to make a coat for my older son Michael in the 1950s. I can’t remember when he died. )

I finished the 7 years school in 1930. To continue my education I needed to get some work experience. It was difficult to find a job. There was an employment agency in a lane in Grecheskaya square. There were long lines of people near this agency and I remember how my friends and I stayed overnight near the sculptures of two lions in Deribassovskaya Street waiting for our turn to get inside the agency. I obtained a recommendation to a vocational school at Odessa cinema factory: this was how Odessa cinema studio was called at the time. I studied at school three years and worked as an electrician at the studio. Every day I commuted to the studio by tram #25. It was always overcrowded and people were hanging from its rear and sides. When a trapezium-shaped wagon rode in a street it hitched up a tram occasionally. I remember snowdrifts in Odessa on the first winter of my work at the studio. My mother was very worried about me since I was only 14 years old. To make sure I got to work all right she managed to find a phone from where she called the studio. This was the first time my mother and I talked on the phone. Our voices sounded different on the phone and to make sue that I was I, my mother asked me what I had for breakfast. She believed that she was talking to me when I said that I had semolina for breakfast. My wife and I still laugh remembering this.

I joined Komsomol 7 at vocational school, but I never took an active part in it. All I can remember is that I attended Komsomol meetings. At that time communists and party leaders used to report to people on their activities and Komsomol members were to attend Party meetings where they reviewed Party activities in detail.

I met Yuzef Chizhyk at work and we became lifetime friends. We subscribed to big volumes of German catalogues from abroad. We were very fond of reading these catalogues thinking about profession of electricians and further education. We had poor German and could hardly understand what was written there, but we liked interesting photographs of electric and other equipment. We read a lot in Russian. Before World War II, I was fond of Conan Doyle [Arthur Conan Doyle, 1859–1930, was an English author, created the character of amateur detective Sherlock Holmes.]

In the 1930s Torgsin stores 8 were open in Odessa selling food products for gold and foreign currency. At the same time people were not allowed to deal with foreign currency in private. They were arrested and persecuted for foreign currency operations. My father was doing better at his work and decided to buy few dollars to keep them as savings. He bound then in carton. Our kitchen door led to the attic of an adjoining house. There was carton in place of glass in this door and my father kept his dollars in this carton. The person who sold these dollars to my father reported on him. He stayed in prison 24 hours. He never told us what they did to him there. NKVD 9 employees convoyed him home and he showed them his hiding place. They took away my father’s dollars. This was called in Odessa the ‘gold fever’ and took place in 1932–1933s. Many people were arrested on false charges.

Yuzef Chizhyk and I entered short-term communication course in the Odessa Communications College. I finished the course in 1933 and entered the Faculty of Telephone and Telegraph Communications. I was a student during the period of famine in 1932-1933 and had meals at our students’ diner. We had all food made of soybeans: soup, cookies and a drink. I don’t remember mass arrests in 1937 [during the Great Terror] 10, but I remember us marching at our military training classes singing: ‘We shall sing a song about Yakir, our army commander!’ and later this Yakir 11 was arrested and executed. A group of military commanding officers was executed at this period of time. In 1941, when the Great Patriotic War began it became clear how unprepared we were – the army was beheaded. I didn’t believe this commandment was guilty. I didn’t have any fear for my family or me: we didn’t belong to those circles that had to be concerned about their position. In 1938, after finishing my fourth year I was awarded the rank of junior commanding officer of a platoon.

There was a group of five friends in College: Akiva Averbuch, Yuzef Chizhyk, Zhora Shcwartz, Fyodor Tomchakovski and myself. Akiva and Yuzef were Jews, Zhora was German and Tomchakovski was Polish. Chizhyk left the college after his first year of studies and the rest of us finished it. Tomchakovski lived in his own house in Slobodka [Neighborhood on the outskirts of Odessa]. We got together there to prepare for our exams. We went to the seashore in Lanjeron, Otrada, Arkadia [town beaches in Odessa]. But with my parents we went there seldom. My father couldn’t stay in the sun since he had very white skin that easily got burned. Generally in those times people didn’t go to the seashore like nowadays. Maybe my parents considered it improper to take off clothes in their age.

My brother Fima studied at the factory vocational school in the Marty shipyard. Ghenia studied at school – it seems, it was school # 68. She studied well and was a nice girl. She read a lot. She studied to play the piano, but when she began to have cramps in her fingers she gave up her studies. Our parents bought her a piano, but there were termites in it and they sold it before the war. Ghenia had many friends, but I don’t remember them. I only remember one friend that had something wrong with her eye and combed her hair to cover it. Ghenia finished school in 1941.

In 1936 I met my future wife Tatiana Krupnik who visited her older brother Moisey Krupnik living in our house. Our neighbor Rosa Kolesnik, a very sickly woman, used to sit under the mulberry tree in our yard and Tatiana used to stop for a chat with her. I watched her from the window. I liked her much. I kept looking at her. She fit a Jewish saying of being ‘a kleine, a Schwartz, a springendik’ [little, black and fidgety in Yiddish]. They usually say so about a flea, but Tatiana was little, well-fed, black-haired, vivid and very pretty. I was shy and had no experience with girls. Since I was an electrician I was helping with electrical maintenance of our house. My friends and I made a plot and I made a short circuit to get into Tatiana brother’s apartment to meet her, but it didn’t work. Finally I gathered my courage and approached her in the yard where she was with her one-year-old nephew. I didn’t find anything better than: ‘Have I seen you somewhere?’ She studied at the vocational school at the Medical college. I’ve been to the morbid anatomy room there and lied that I had seen her there. Anyway, we made our acquaintance.

Tatiana was born in the Jewish town of Dzygovka, Vinnitsa region in 1920. She was the fifth daughter in her family. The last and favorite one. Her parents Srul and Hana Krupnik were also born in Dzygovka. They were deeply religious. Tatiana was raised Jewish. The eldest sister Ida Mostovaya was born in 1907. She lived in Odessa with her Jewish husband Petya and two children. During the Great Patriotic War her husband was on the front and Ida with daughter Raisa and son Marcus were in Uzbekistan. After the war they lived in Tashkent. Ida died in 1983. Raisa and Marcus live in Israel. Tatiana’s brother Moisey Krupnik was born in 1909. He lived in Odessa. His wife Ania was Jewish. They had a son Bencion, in the summer 1941 their daughter Tamara was born. Ania and children were evacuated to Tashkent. Moisey perished in 1942 in Sevastopol. Ania and Tamara live in Odessa. Bencion lives now in Haifa. Tatiana’s second brother Iosif was born in 1912. He was in the army but not on the front during the war. After the war he lived in Moscow. He married a Jewish girl Sopha. Iosif died in 2002. His daughter Ludmila lives in the USA, and the son Boris lives in Moscow with the mother Sopha. Tatiana’s sister Rosa Poliak was born in 1917 and perished in ghetto in 1941 in Vinnitsa with her two years old son Milia.

When Tatiana turned 15 in 1935, she went to Odessa to enter the Stomatological College. She failed and went to study at the vocational school. After finishing this school she entered the Medical College. We decided to get married in 1939. I was in my last year at the Communications College and Tatiana had finished her 2nd year. We got married on 25 March 1939. We had a wedding party for the family: my parents and Tatiana’s parents Srul and Hana. We had a traditional Jewish wedding ceremony at home, but there was no chuppah. Our parents’ acquaintance, an old religious Jew conducted the ceremony. I recited a prayer that I had written for me in Russian letters. After the ceremony we had a wedding party. A day later we had a civil ceremony in the registry office near the Opera Theater. After the wedding Tatiana and I lived with my parents. Tatiana got along with my mother very well. Tatiana likes to recall the way they met. My mother took her hands, pressed them to her chest and said ‘I’m glad to be able to call you Tilipman’. I wish my parents had lived longer. Tatiana corresponded with my parents when we left Odessa. She became friend with Ghenia. In June 1941 Ghenia wrote Tatiana to greet her with the birth of her niece Tamara, her brother Moisey’s daughter. Tamara was born on 17 June 1941, five days before the Great Patriotic War.

In summer 1939 I finished my College with honors and we moved to Smolensk where I got a mandatory job assignment. 12. Tatiana could continue her studies in the Medical College in Smolensk. I became a civil communications engineer in communication department of Byelorussian military regiment. Before 1940 its headquarters was in Smolensk. After the annexation of Western Belorus [and Western Ukraine] 13 the headquarters moved to Minsk. I moved with the headquarters and Tatiana stayed in Smolensk to finish her 3rd year in College. In summer 1940 she joined me in Minsk. She went to study her fourth year in the Minsk Medical College. We got an apartment in an officers’ house in the military housing district of Antonovo Аin 2-3 kilometers from Minsk. Our neighbors were a young Russian couple. The husband Alexei Pudovkin was a builder and also worked in the Byelorussian regiment. We became friends and visited each other.

After finishing her fourth year Tatiana was supposed to have practical training in a hospital in Pinsk or Brest. I recommended her father to obtain an invitation letter for her to work in the hospital in Chernovtsy village, Yampol district, Vinnitsa region. Tatiana went to stay with her parents and I stayed in Minsk. In summer 1941 the Moscow Art Theater came on tour to Minsk. I got a ticket for 22 June and was to go to the theater with a colleague of mine. I got up and had a snack on 22 June. Since I was alone I didn’t even turn on the radio. I packed my gray suit and brown shoes to change to the theater in the evening and went to work by tram. It was Sunday, but I had some urgent work to do. The first thing I heard when I got into a tram was Molotov’s speech 14. The War! I was a reserve officer and I believed it was my duty to go to the headquarters. I never came back home. In the afternoon German planes were already flying over Minsk. There was a German car caught near the headquarters. It was camouflaged to look like a Soviet ZIS car, but there were German uniforms loaded in it. Although I had documents with me I was thoroughly inspected before I was allowed to enter the headquarters office. They were concerned about penetration of the enemy’s intelligence. I was engaged in packing secret documents. We stayed in the office overnight and slept on desks.

We continued our work next morning and in the evening and then the following evening we were taken to dig trenches in the Urochishche area, near Minsk. There were planes flying over Minsk and flares with which saboteurs signaled to German planes. Minsk was bombed continuously. All civil employees were given military ranks. My rank that I was awarded in communications school was first lieutenant. I received my uniform: a khaki shirt, galife breeches and boots with leg wrappings. Those leg wrappings were amazingly uncomfortable slipping down all the time. I also received a dark blue flask with a wooden cork. I also had a German trophy aluminum flask with a screw top and plywood encasing for thermal effect. What I would say everything that we got was a kind of junk: they were not too generous about providing young officers with good quality things. In the morning the storehouse got burned we heard, and officers’ uniforms and everything else was gone.

Germans were advancing fast. Three days later our military units were leaving Minsk. We were evacuating on trucks with benches. There was a many-kilometer log march of people escaping to the east carrying their luggage. There must have been saboteurs in this march as well. They were trying to stir up panic in the crowd screaming ‘brothers, don’t leave us’, etc. There were German planes attacking us many times and scattered around to hide in the surrounding. We arrived at Mogilev where we saw superior commanding officers including Voroshilov 15 in his leather jacket. He arrived there to arrest other commanders charged in allowing retreat. Commanding officer of Byelorussian Special Military regiment General-Colonel Pavlov and Communications Chief general Grigoriev were arrested. [Dmitri Grigorievich Pavlov, 1897–1941, was a Soviet military commander. He was arrested under false charges and later rehabilitated posthumously.]

The army was retreating. People kept asking ‘Why are you leaving?’ and we were promising to come back, but we didn’t know when. When we were in the vicinity of Vyazma, we heard the roar of German planes flying to Moscow every night. The radio announced how many bombers attacked Moscow every day. The Soviet troops were retreating and we didn’t know when we would manage to return, but there was no despair among soldiers.

In August 1941 I was sent to army 29 at the Kalinin front. I received my uniform that finally included high boots. I chose my size of boots that was a mistake since I had to wear thicker flannel foot wraps in winter and my boots turned out to be too tight and I was in pain for few days before I managed to get a bigger size of boots. I also received an overcoat and then when I was at the Ukrainian Front during the cold winter of 1943 we received sheepskin vests. I’ve kept mine until today. We also received warm gloves and those that were at the battlefield received white robes. We wore our overcoats and slept on it using it as a wrapper.

We had warm clothes and sufficient food. I don’t think people ate better food in the rear. We received packaged food and hot meals: cereals and canned meat. We received fresh and dried bread. There were horses in the army and when they got wounded their meat was used to cook food. Once our first sergeant brought us horse meat and said ‘This is nice meat. Would you like some?’ I wish I had at least tried it then.

I was commanding officer of Communications Company in army 29. We were responsible for telephone communications between the army and divisions. In the first days of the war it became clear how unprepared we were to many situations. There were special two-wire phones: we had to install many kilometers of wiring to support communication between the headquarters and divisions. We had not sufficient quantities of wires and installed one wire instead of two: the ground was the 2nd wire. To support the low-point telephone circuit we grounded one wire with a metal rod. The same was done on the other end: one wire was connected to a phone and another – into the ground with a rod. If the ground was conducting: wet or black soil, it was bearable and made it possible to hear at some distance, but hearing was impossible when it was freezing or when the ground was dry. Besides, if the ground serves as conductor it is all right for one line of communication, but when this line supports communications between 5-7 divisions supported by one wire, all conversations could be overheard since they all had one common conductor – the soil. There were antediluvian phones. A telephone operator had to shout into the receiver having it tied to his head turning the handle of a switchboard. German phones were more up to date: they only had to push a button to turn them on. Also there were inappropriate call words at the beginning and one could hear a telephone operator sitting in the headquarters yelling ‘Fire! Fire! –I am the farm!’ and then an officer on duty running toward him ‘Where is fire? On a farm?’ – when those were just call words. We had miserable equipment. The radios to support communications between the headquarters and divisions were transported on horse-driven wagons at the beginning before we got special transportation trucks. There were also shoulder radios: dozens of kilos to be carried on our backs.

Success of military operations depended on the quality of communications to a big extent. When we were retreating the only communications equipment available were radios that had limitations in supporting communications and our troops often got into encirclements for the lack of communications. There was an order ‘Not a step backward!’ that meant that a unit could only retreat when they got such order and the order could not reach those that were in encirclement. Germans were more maneuverable. Their infantry had transportation means while our troops only walked. At the Kalinin front a group of communication operators was sent to military units in Rzhev. While they were on the way there the German troops broke though the front line and they got into encirclement. It was next to impossible to escape from encirclement in open area or in towns. I remember I was on the phone when Communication Chief of the Front came and took the receiver from me. He talked to our operator on the other end of the wire ‘I order you to retreat!’ when the line was cut off. We had no information about our operators: whether they were captured or perished. They were listed as ‘missing’ and there were many such cases.

There were many cases when Germans captured our messengers and then they bombed the location indicated in the message. Once before my eyes a subdivision of our unit perished. They were on a farm when German planes dropped three bombs hitting directly their dislocation. Our communication unit was in about half of kilometer from this place.

In late 1941 we were at the Kalinin front. It was Christmas. German commandment provided Christmas parcels to their units: schnapps, tinned meat and chocolate. Germans were advancing to Moscow and there was Deshovka village (the word ‘deshovka’ means ‘cheap junk’ in Russian) on their way. This Deshovka turned out to be very costly for us. Several times it passed from our troops to German troops and back again. When our troops beat German troops out of their blindages they would find German schnapps and get drunk and then German troops would beat them out of there. Our communication point was in some village church and there was Commander of army 29 standing beside me. He heard that this village had passed several times between German and out troops… He demanded that I connected him with commanding officer of the division. I remember his order word by word: ‘You, son of a bitch, colonel Kupriyanov! Just get all cooks and communication operators and lead them in attack! I want you to take control of this Deshovka!’ This meant that he was sending the young and inexperienced onto the battlefield. Such orders caused many deaths. This happened often. All battle operations were conducted under the motto ‘For Motherland! For Stalin!’ and people died for this. One had to follow orders in the army. They followed orders. It wasn’t too bad when there was artillery support of infantry troops.

Commander of army 29 was noted for his despotic nature. He used to walk with a stick at the Kalinin front. He could easily hit an officer, even of senior rank. Once our truck was moving on a road and commanding officer of our communication regiment didn’t pull over seeing the vehicle of our army commander that got stuck there. For this commander didn’t submit lists of officers subject to awards for six months.

I didn’t have any information about my family from the beginning of the war. I received the latest card from my father from Odessa in August 1941. I knew about German atrocities against Jews from newspapers and kept writing my father to leave Odessa. After Odessa was occupied I received a letter from my friend Akiva Averbuch’s father in October 1941. He stayed with my parents for some time before he evacuated and also tried to convince my parents to evacuate. My younger brother Fima was in the army near Odessa and my parents couldn’t leave the town without knowing what had happened to him. Shortly after Odessa was liberated in 1944 – I was at the front in Poland – I received a letter from my cousin brother Naum Davidovich. He returned to Odessa from evacuation. He wrote that my parents and sister perished in Domanevka 16 camp for Jews in 1942 and Fima perished during defense of Odessa in 1941. When I returned to our house after the war or neighbors gave me a card that Ghenia’s friend wrote her from the front. I didn’t even know that she had a young man who was writing her from the front.

My friend Yuzef evacuated to Siberia. He was released from service in the army due to epilepsy. My fellow students and I kept in touch through him. Akiva Averbuch was at the front. Zhora Schwartz wasn’t taken to the army due to his German nationality. He lived in Novosibirsk, I guess. Yuzef wrote me in late 1941 that he had seen my wife Tatiana in a train on Alexikovo station near Stalingrad. I wrote letters to this Alexikovo and employees of the post office were very sympathetic, but they could do nothing to help me. Tatiana was not in Alexikovo any longer. She bumped into Alexei Pudovkin, our friend in Minsk and he suggested that she wrote to the Communication Department of the Soviet army. She did and they sent her my field mail address. I received a letter from Tatiana in June 1942. She evacuated with her parents and older brother Iosif. Her brother managed to evacuate his family and parents on a wagon driven by two horses. They crossed the Dnepr River in the vicinity of Kryukovo station. They went to Stalingrad by train and from there they headed to Turkestan station in Kazakhstan [3,000 km from Odessa]. Tatiana was a physician in Urtak kolkhoz. She lived with her parents. The kolkhoz accommodated them in a house with a garden.

I would like to say that during the war people treated letters with special care. Field mail communications were very reliable. At least letters found us wherever we moved. There were never long delays with delivery of letters to and from the front. A postman at the front was a very special person. Letters from the front could have been different; they might bring sad news, but letters from the rear usually brought good news from families. I do think that a postman is a very kind and hearty profession, military postmen in particular. My wife and I even established our own communication at the front. I wrote her ‘You will look at the Moon and so will I and it will be our date’ – like satellite communications nowadays. I’ve kept few hundreds of her letters through the war. I carried them in my backpack. My letters to her were lost in evacuation.

We had different lodgings at the front: during retreat, interval or advance. When we were retreating toward Moscow or advancing with the Kalinin front we lodged in dugouts with wooden logs and soil on top. There were two or three layers on top to protect a dugout from bombings and each layer was placed crosswise on a previous. Like they sing in a song ‘…Our dugout in three layers…’ It also protected from shells. Once commanding officer was killed with a shell at the entrance to his dugout, but he would have survived had he stayed inside. During an interval we planked the walls with wood or thick branches. We made two-tier plank beds. We had oil-lamps for lighting. We made them from tank shell cartridges, 5-6 cm in diameter with one end squeezed with a cloth wick squeezed in it. We dipped this wick in kerosene or benzene. It produced a lot of black soot and it made it difficult to breathe in a dugout, but it kept it warm, on the other hand. There were 8-12 tenants in a dugout. In our advance march we lodged in blindages left by Germans. Near Moscow we lodged in a dugout made by Germans. Germans liked birch trees. There was a small table and a stool made of birch wood at the entrance to the dugout. The walls inside were also decorated with birch wood. There was a small stove made from a bomb box.

I was chief of the telephone facility of a regiment at the Kalinin front. The chief of telegraph facility was Kostia Shendera. We happened to have finished the same faculty in the same college, only we studied in different periods. He was a 5th-year student when I entered the college in 1933. We often recalled our college and common acquaintances. Once I recalled how we, 1st-year students went to work in the fields in Novaya Odessa in Nikolaev region in 1933. We got together in the evenings and sang and talked. I remembered a Ukrainian song that someone I didn’t know sang: ‘It snowed in the month of June when an old man fell in love with an old woman, cause he liked her…’. Kostia said ‘I sang it’.

I remember my 26th birthday on 24 April in the Kalinin front. We had just got an interval after a battle. There was some kind of a buffet in the army headquarters during such intervals or remanning of units. They had kwass [a soft drink] smelling of burned bread a little. My fellow comrades got to know that it was my birthday and decided to celebrate. We were young. Kostia Shendera sent his telegraph operators to get some self-made vodka in a nearby village. We mixed kwass and vodka and got a nice drink. I put on my suit and shoes that I had with me when I left my home in Minsk on 22 June 1941: whatever was left there. I dressed up and we partied. Kostia sang popular songs and romances. He sang the ‘Metelitsa’ [a Russian folksong]. He had a very good voice. Since then it became a tradition to celebrate all birthdays. I still have the list of my fellow comrades: there are 28 names on the list. I greet them with their birthdays every year. Now there are fewer on the list…

Kostia was Russian and so was commanding officer of my battalion: Vitali Vasilievich Legeida. There was no anti-Semitism in our circles in the army. There were tatars in my unit and there was Brodski, a Jew. However, there were demonstrations of anti-Semitism among high-level officers that were responsible for awards. I faced it when I was to be awarded a medal ‘For combat merits’. Awards were usually handed during intervals when the army units were remanning. The ones that were on the lists for awards were notified in advance. I got a notification and even prepared a speech, but it never got to it. My subordinate received an award and I don’t know for what reason. We were not supposed to ask questions. When I was to be awarded for the second time I was told that it was going to be a ‘Red Star’ order, but instead I was awarded a ‘For combat merits’ medal. I received my ‘Red Star’ when we were near Kiev. My nationality played its negative role in my promotion in the army and after the war.

In February 1943 a new tank army was formed near Moscow on the basis of our army 29. Its commander became Michael Efimovich Katukov [Michael Efimovich Katukov, 1900–1976, was a Soviet commander, Marshall of tank armed forces in 1959, Hero of the Soviet Union in 1944 and 1945. During the Great Patriotic War he was commanding officer of a tank division, brigade, corps, guard tank army since 1943.] By that time the rear manufactured sufficient quantities of weapons. The tanks that we had at the beginning of the war in 1941 were not fir for this kind of the war. We got a new division of T-34 tanks. We got fresh forces of female telephone operators in our communications regiment. The majority of them were from Moscow. Male operators mainly were involved in installation of telephone lines and other hard work. Many of my fellow comrades are still living. I still communicate with Ania Krotova, nee Dyomina, a telephone operator from my regiment. She married a tank man Michael Krotov at the front, Hero of the Soviet Union. My wife and I meet with them when we visit our son in Moscow.

In winter 1943 the battle of Stalingrad was coming to an end. Our tank army was transported to the vicinity of Stalingrad by railroad. By the time we arrived in this area the battle of Stalingrad was over. This was Stepnoy front that was later renamed to Voronezhski. After our successful completion of the Stalingrad battle Germans intended to gain revenge at the Kursk salient. In summer 1943 near Prokhorovka 17 two heavily armed tank units collided. There was the third tank army near Prokhorovka and our first tank unit was deployed further to the south in the direction of Kharkov. Our army cut the roadway Kharkov-Poltava. We were holding back German units that were striving to cross the Kursk salient. Katukov, commander of the tank army, was at the vanguard tank unit on the firing line and we were responsible for supporting his communication with the army headquarters. He and commander of the brigade were watching the battle and gave verbal commands to the army headquarters that was developing the tactics of the battle: where to send forces, what additional units to allocate, involve artillery or even air forces. During the battle commander was in a trench with a tank over it; it made a reliable hiding spot. Commanding officers of tank units also usually stayed in such trenches. Communications operators that were responsible for supporting communication with the army headquarters were also in the trench with commander.

The tank army was moving ahead fast covering dozens kilometers during a battle. They advanced so fast that they lost communications since communication units were left far behind. To avoid this situation a small group of communication operators went ahead to the location to make the headquarters. This group was called a mobile control unit. Prior to a battle the army headquarters established communications with frontline and corps. They identified the movement direction and appointed a group of operators: radio and homing communication to support communication for commander when he arrived there. I remember how after defensive battles near Kursk our army advanced ahead very quickly. We, communication operators, had to move to the next command post to establish communications. We had two vehicles with soldiers and equipment. Commanding officer of our battalion Legeida was on one truck and I was on another with communication operators. It was summer and the heat was oppressive. The tanks turned soil into dust. We were moving in this cloud of dust. There was a lot of tension. Legeida was a soft and intelligent man open his cabin and yelled at me ‘If you are going to be late, you…’ and he continued in a whole set of curse language. We came in time. We corresponded after the war and often recalled such moments.

During one of those battles one of my operators – Brodski, a Jew, perished. I don’t remember his first name. We addressed each other saying the rank and the last name: lieutenant Tilipman, private Brodski… I don’t remember where he came from, but I remember that before the war he was chief of Centrospirt trust [alcohol sale]. However, he wasn’t one of these dealers and wheelers. He was well liked and respected. When our first sergeant brought food for distribution he was always appointed to distribute sugar, tobacco and other products. During an offensive he was sent to establish communications with our operations department when German bombers began dropping bombs. Brodski got between three bombs that literally tore him to pieces. There was nothing left to bury. There were special burial troops. They were also responsible for keeping records of the dead and all relevant information: the place and date of death. Commanding officers had to notify their families and give them information about the burial location.

At the beginning of the war I was first Lieutenant and then I became lieutenant-technician, commander of a platoon. In 1943 an order was issued to confer the rank of captain to officers with higher education. After the Kursk battle I was given the rank of captain.

After the offensive and liberation of Chernovtsy our army was moved to the rear. We were to be remanned and meanwhile deployed near a settlement in a forest from where we went to Chernovtsy for spoils of the war: food and other. I went to get some trophies when we were advancing to Kazatin in Vinnitsa region. There we got a German diesel fuel vehicle with a telephone facility. Communications people also took communication cables and everything else they might be in need of in future operations. There were special trophy units that gathered trophy weapons. I had a trophy German carbine. I don’t even remember how I got it. We also took trophy fuel that was always in demand. I shall not hide the truth that we also got alcohol as trophy.

Besides communications regiment there were communication companies in our regiment. Commanding officers of two of them were my friends: captain Zhuk and captain Yunyshev. Captain Zhuk was sent to the penal battalion due to trophy fuel. Captain Zhuk got some fuel stocks as trophy, but instead of reporting to the fuel department he used it for the needs of his company. At that time commanding officers reviewed the recent operations to award the distinguished ones. When they were reviewing performance of officers and soldiers of captain Zhuk’s company they recalled this fuel. There was one ‘osobist’ – they called so officers of special department [NKVD units in the Soviet army]. This ‘osobist’ participated in a dinner party where he got to know about the fuel during the conversation and then wrote a report about captain Zhuk misusing the fuel. Zhuk was reduced to the rank of a private and sent to a penal battalion. He was a still a communications operator. It was next to impossible to survive in those battalions. They could only hope for good luck. They were always ahead of any offensive. I received a letter from him and even tried to find him later. Zhuk was wounded, but I don’t know what happened to him further on. I don’t know whether he survived. Captain Yunyshev’s story is different. After the war he was in Meissen, in Germany, with his unit and I was in Dresden. Some time in 1947 he visited communications department in Dresden. We met and he told me that he was having an affair with a German woman. He said ‘You know their attitude to German women in our country and I am in love with her. What do you think about it?’ ‘You know that you can be expelled from the Party and reduced in ranks, etc.’ Later I heard that he was transferred to a unit in Western Ukraine fighting ‘banderovtsy’ 18. He was shell-shocked and demobilized. Then he got married with a Ukrainian woman and lived in Kharkov with his wife. My younger son Evgeni and I went to Tbilisi via Kharkov by train in the 1970s. We met with Yunyshev. He was a teacher. I corresponded with him all the time. In the late 1980s I went to Moscow where chairman of our regiment veteran organization, who was my subordinate during the war, told me that Yunyshev died.

In winter 1944 we were in Poland. Polish residents had a friendly attitude toward us. In Niedzwiada village boys used to sing: ‘Polska hasn’t died yet and it will not…’ Then there were words that they would make Germans to wash their boots. We were accommodated in a house. There was a Polish family of a husband, wife and a young daughter living in the house. This family invited us to a celebration of liberation of Poland. Our telephone operator, private Vladimir Miakushko, that was also our logistic supervisor, brought some food products and we set the table. We proposed a toast to victory, of course. There was an interesting custom with the Poles: they had their classes filled to the brim and when touching glasses they tried to let their wine overflow into somebody else’s glass. We had lots of fun. Later our tank brigade took part in liberation of Warsaw. In 1944 I became a candidate to the Communist party and I joined the Party in Odessa in 1948.

Tank units need lots of fuel to support operations, repairs and replacement of tanks. Therefore, army rear services need to be very reliable. There was no rear communications department included in the army staff while there was a great need in one. So, the department was formed and its chief was Lopukhov. He came from Moscow where he was involved in metro construction before the war. In 1944, when we were advancing successfully Moscow began to call back specialists required in public economy. Lopukhov demobilized and went back to Moscow and I was appointed as part-time chief of the rear communications services. However, I kept positions of chief of a company or equipment yard or a reserve unit. My wife Tatiana received allowances by my military certificate. When I had a full-time position in my regiment there were no problems with this certificate, but then when I began to change positions there were delays with payments or reevaluation of the amounts.

When we entered the territory of Germany we stayed in abandoned houses or apartments. Some time before the end of the war we found a top hat, tuxedo and cigars in one apartment. We dressed up our telephone operator Alexei Ilinski, photographed him and sent this photo to his home. There was also censoring of letters in the army. We had to face this department. At night they woke me up and ordered to come to chief of rear services of the army colonel Kon’kov. He showed me the photo: ‘Yours’. I said ‘Yes, mine’. He reprimanded me ‘What are they doing here? Is it during field action or recreation?’ There was another time that I faced this censorship when I sent my wife a picture from a medical book. It was a picture of a human being and when unfolded it revealed a picture of the human body. So, I added a short note for a censor ‘Dear censor, if you find it impossible to send this to the addressee, please, send it back to me’. My wife received it.

The Katukov’s army ended up in Berlin. The army headquarters were in 25, Druchenstrasse in Berlin. I went there on business on 8 May 1945. I had a map of Berlin withal streets indicated on it. Although Berlin was ruined in the center it still made it possible to find any location. I remember meeting Kostia Shendera in the army headquarters. He and I listened to an English radio channel in Russian. It announced that capitulation was going to be signed at 11 pm. I decided to go back to my unit. Shendera showed me a shortcut through channels. He didn’t know they were blasted and access to them ruined. To make a long story short, I got lost. I managed to find my way by the lights of moving traffic. I got to the central street and from there I made my way to my unit. We waited for the announcement about capitulation: the clock struck 10, 11 pm, midnight. We were waiting. We were listening to the radio when, I believe, 5 minutes past one it said that there was going to be an important announcement. And indeed, at ten minutes past one our renowned announcer Levitan announced fascist Germany signed unconditional surrender. [Levitan Yury, 1914–1983, was the announcer of All-Union State Radio. He delivered all most important official information, also during the Great Patriotic War.] Our joy was enormous! Those that couldn’t keep it to themselves started shooting in the air. From joy, of course. So I met the Victory Day in Berlin.

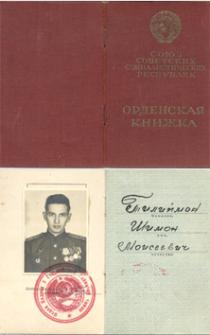

I finished the war in the rank of captain. I had several combat awards: two medal’s ‘For combat merits’, order of ‘Red Star’, medals ‘For liberation of Warsaw’, ‘For capture Berlin’. I stayed to continue my military service in Radeboil near Dresden in the communications department in the army headquarters. In September there was a war with Japan 19. In autumn I got a two-week leave. I went to visit Tatiana and her parents in Turkestan. On my way back I took her back to Minsk to finish her studies at the Medical College. After finishing it she joined me in Radebeul in 1946. Tatiana was involved in public activities in the women’s council of the army. We still laugh that I was on battlefields while she shook hands with commander of the army Katukov. The highest rank I had to deal with during my service was a general, chief of communications while she had interface with the army commander. Many officers’ wives came there. Kostia Shendera’s wife was a shop assistant at the military department store. The wife of Valeri Legeida was a telephone operator in our regiment. We were all friends. After demobilization Kostia lived near Vinnitsa. I saw him at his 70th birthday in 1971 for the last time. He was a heavy man and suffered from hypertension. Tatiana and I were planning to come to his 75th birthday, but he died before. Valeri Legeida is living. He wrote us that his wife died.

In 1947 our son was born in the army hospital in Dresden. We named him Michael. My wife’s parents had moved to their eldest daughter Ida near Tashkent. In 1948 I sent my wife and son to them. Tatiana and our son went to Moscow biplane and from there took a train to Tashkent. When Tatiana left I began to submit requests for demobilization. I wrote a letter of request to the Communications department of the Soviet army asking. I expected some problems in this regard: the army did not appreciate jumping over one’s head. I was lucky. There was a vacancy of chief of a communications department in Odessa. My predecessor was sent to serve in the army abroad. I went to work there in 1949. I remember returning to Odessa. The train arrived early in the morning. The streets were deserted and there were porters with carts in front of the railway station. I walked to Deribassovskaya Street and stayed in the Passage hotel. Then I searched for my cousin brother Shymon Tilipman. What surprised me in Odessa was that there were vendors on each corner. I had legal grounds to move back into my parents’ apartment, but there was another tenant in it already: an invalid of the war. Besides, I would have been terrified to reside there when my family perished. Local authorities gave me a kitchen in a communal apartment 20 in Seminarski Lane near the headquarters of Odessa military regiment. I went to Moscow and then to Tashkent to take my wife and son home. The trip from Moscow took me four days and I had to sleep on the third birth intended for luggage. The train was slow.

We returned to Odessa. I got in touch with Yuzef Chizhyk who returned with his wife and children from evacuation in Siberia. We had another friend: my fellow comrade Semyon Goldshtein and his wife Inna. She was a doctor. My cousin brother Shymon Tilipman, his wife and son lived in Odessa. We were young and valued the joys of peaceful life. We celebrated all birthdays and Soviet holidays: the Soviet Army Day 21, October Revolution 22 Day. We always got together at Yozef Chizhyk’s home to celebrate New Year. We lived in a big room in 19, Pirogovskaya Street in the early 1950s. There were 18-20 people at our parties in our room.

In 1951 our second son Evgeni was born. We named him after my sister Ghenia. When Stalin died in 1953 I was serving in the communications unit in Odessa. We all feared a coup or some dramatic changes. There was to be a replacement of Stalin. We were ordered to stay in the unit. However, nothing happened. Our people were taught to have no different opinions. The military that were at the front during the war respected Stalin a lot. We believed that he lead us to the victory along with Zhukov 23.

In 1954 our older son Michael went to school # 59 near our home. Tatiana was eager to go back to work. She couldn’t find a job in Odessa for 12 years. She applied to the regional health department with requests for employment many times, but they replied that she didn’t have to go to work being a military’s wife. In 1958 she went to the Ministry of Health in Kiev. The Minister happened to be a kind person. He issued a letter addressed to the regional health department ordering them to help Tatiana find a job to keep up her qualifications. She started work in Illichevsk 24. There was no regular transportation to Illichevsk and Tatiana often had to get a ride on trucks. Commuting took a lot of time. She also had to take care of the household and take care of our sons. Michael was in the 4th form and Evgeni went to school. Four months later Tatiana found a job in a local polyclinic in Deribassovskaya where she worked as a neuropathologist until she retired.

I was earning well and so did Tatiana and we were quite well off. In the early 1950s we bought our first TV set. We spent our summer vacations with Tatiana’s parents in Chirchik near Tashkent. We spent time with friends and went to the theater. Before the war Tatiana and I went to the Jewish theater. I couldn’t understand Yiddish that well and Tatiana translated for me. After the war we went to the Ukrainian and Russian theaters – in one of them performed in Ukrainian and in the other one in Russian. In summer theaters from Moscow came on tours and we attended their performances. The thing is, our children didn’t need us any more. I remember performance ‘And then there was silence’ [after the modern American writer Vina Delmar’s play] staged by the Mossoviet Theater with Ranevskaya and Pliatt [famous Soviet actors]. We preferred the same play staged by our Odessa theater. We thought that Pliatt was overdoing his acting. We also went to the Opera Theater, but not that often. We subscribed to Roman-gazeta [publication of fiction issued twice a month in Moscow], Rabotnitsa [Women-worker, a monthly social and political magazine issued in Moscow], Zdorovie [Health, a monthly scientific popular magazine issued by the Ministry of Health in Moscow]. We still keep articles from this magazine with health recommendations. We also subscribed to newspapers: Krasnaya Zviezda [Red star, daily military and political newspaper of the Ministry of defense, issued in Moscow], Pravda [Truth, the main paper of the Communist Party of the USSR]. We always read articles in newspapers, but we did understand that what they wrote was different from what things were in reality.

In 1966, after an earthquake in Tashkent, we took Tatiana’s parents to Odessa. I demobilized from the army that same year and received a pension after 25 years of military service. I was 50 years old and wanted to go to work. It was difficult for a Jew to find a job. There was a vacancy at a plant, but when they heard that I was a Jew they refused me. It happened several times until I met my former fellow student Michael Tesler, a Jew. He helped me to get an employment at the Standardization Center in Odessa where I was employed as an engineer. In 1968 I received a new 4-room apartment in a 5-storied house in Cheryomushki, a new district of Odessa, built with the involvement of Standardization Center. This is where we live now.

In 1964, 25 years after we graduated, I organized a reunification of graduates of our college. Our graduates were working all over the Soviet Union. Many of them, including my old friends, came to this meeting. Akiva Averbuch came from Kherson, Zhora Schwartz came from Kazan. He came with another graduate of our college Kaminski. We met him at the airport and drove the car around Odessa. He was very happy to see us and talked to us fondly about Kazan, how much he liked it and how wonderful the town was, when all of a sudden he said when we were driving along Pushkinskaya Street ‘Pull over, I shall kiss the stones of the pavement!’ Odessites shall always be like this: they know no better town than Odessa. Zhora Schwartz visited us about five years ago, in 1998. He is in good shape: we went to the seashore with him. I often met with Akiva Averbuch – he lived in Kherson. He suffered from hypertension and when he visited us Tatiana checked his blood pressure before offering him a strong drink. Akiva died in Kherson in the late 1990s. I was away and didn’t go to his funeral. Yuzef Chizhyk and his wife went to the funeral. Yuzef Chizhyk died in 1996. One of his sons lives in Berlin, Germany. Fydor Tomchakovski lives in Slobodka. My wife and I always go to see him when going to the Jewish cemetery to the graves of our dear ones.

I remember my young years at the front. The friendship that started at the front is the strongest friendship ever. My wife and I have kept in touch with my friends. We corresponded and met with them and mailed greetings on their birthdays. Few times my wife and I went to celebrate 23 February, the Soviet Army Day that we also celebrate as the Day of the first guard tank army with my fellow comrades in Moscow. In summer 1976 we came to Moscow to come to the grave of Marshall M.E. Katukov, our commander. He had died six years before we got together to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the army in Moscow on 23 February 1983.

In 1962 my older son Michael went to school 116, with advanced studies of physics and mathematic. Michael passed an interview successfully and was admitted to the 8th form. He had all excellent marks in this school. There was no anti-Semitism. He had many Jewish classmates. In 1964 he finished this school with a gold medal. 15 other children were awarded god medals along with him. After finishing school he went to take entrance exams to the Faculty of Mathematics in Moscow State University. We were eager for him to be a success and he did enter the university. There was a group of other students from Odessa. They grouped into an association to support each other. There were so many Jewish students at the faculty of Mathematics in Moscow University that it was jokingly called by his friends a ‘cheder with advanced studies of mathematics’.

Evgeni studied in school #90 with the Ukrainian and German languages of teaching. He studied well and was particularly good at history and geography. I brought an ‘officer’s Atlas’ issued in Russian in Dresden after the war: a thick volume including the history of all wars and a detailed description of the Great Patriotic War. We still have this atlas. It is quite worn and shabby after Michael and then Evgeni had it. We always liked books in our family and our sons inherited this from us. In 1969 grandfather Srul gave Evgeni five rubles and our son subscribed to Big Soviet Encyclopedia. We received all five volumes. After finishing school in 1968 finished a preparatory course to the College of Public Economy. He also started work at the factory of manuals to be able to enter an evening department of the Financial Faculty. He was concerned to go to the daytime department being a Jew and considering the existing situation. There was state-level anti-Semitism in Odessa. Now he works as a programmer in Odessa center of Standardization, Metrology and Certification. He is single.

In the 1970s my cousin brother Shymon Tilipman was moving to the USA. My wife and I went to say ‘good bye’ to him and his wife Tsylia on the evening before their departure. They were not at home and we threw what we had with us inside their apartment through a windowpane. At that time contacts with emigrants were not favored in the USSR and we didn’t go to see them at the railway station. Shymon felt hurt and couldn’t forgive us for a long time.

In 1972 my wife’s mother Hana Krupnik died at the age of 89. She was very ill in the last two years of her life. She didn’t remember anything and didn’t recognize our old son Michael who lived in Moscow. We buried her at the Jewish cemetery in Slobodka. Tatiana asked some older Jews to recite a memorial prayer at the cemetery. Tatiana’s father died one year and ten months later in 1973 at the age of 90. He had a sound mind until the end although he was bed-ridden in the last days of his life. On his last night he recited a prayer and blessed us in Yiddish. We buried him near his wife’s grave.

I heard about the establishment of Israel when I was in service in Germany. I’ve always identified myself as a Jew and my family perished due to their Jewish origin. ‘I’ve always sympathized with Israel, but I had to keep silent about my attitudes. I remember Tatiana’s nephew Bencion Krupnik leaving for Israel in the 1970s. He was manager of a shop at a plant and workers of the plant condemned him at the meeting, although his colleagues had always respected and valued him for his qualifications. Thank God the attitudes have changed. In 1986 Tatiana visited her niece Raisa in Lod, Israel. I wished I could go with her, but our family circumstances didn’t allow me to travel there. Tatiana was very impressed with what she saw in Israel. She told us how beautiful the country is. Our relatives live in Israel and we always watch everything they show about Israel on TV. We sympathize with this country. There is no war, but people die at peaceful times because of the terrorism.

Upon graduation from University my older son Michael stayed to work in Moscow. He got a job offer from a scientific research institute. He defended his candidate’s dissertation. 25 Michael married his fellow student Galina Grinberg. She came from Moscow. Her mother is Russian and her father is a Jew. In 1974 Galina and Michael’s older son Anton was born and in 1978 their son Sergei was born. They came to spend their summer vacations with us and we rented a dacha at the seashore, in Arkadia or at station 16 in Bolshoy Fontan. Anton graduated from the Faculty of Mathematics in Moscow State University. He works as a programmer. He was married and has a son – our great grandson Dennis. Our younger grandson Sergei finished four years in Moscow State University and has a job. Galina lectures on mathematics at a Pedagogical College. Michael works at a scientific research institute. He also works as a programmer for a private Canadian company.

I retired in 1988, but continued working part-time for some time. Tatiana retired in 1990. We believed that perestroika 26 initiated by Gorbachev 27 was a big step forward comparing to the period before. We got more freedom. We were allowed to socialize with our relatives abroad. But most important is that the attitude toward Jews has changed. There is no state-level anti-Semitism. As for our material situation it became worse, but not as bad as it became with civilians since retired military receive higher pensions.

In the 1990s the rebirth of the Jewish life began in Odessa. My wife and I are members of the Front Line Fraternity – the association of Jewish veterans of the Great Patriotic War at the charity organization of Gmilus Hesed. We get together every other week and celebrate birthdays. On 9 may we celebrate Victory Day. Besides, we attend Sunday parties at the Moadon club in Hesed where they invite musicians from the Philharmonic or amateur performers. Recently the Jewish theater from Chernovtsy came on tour. My wife organizes celebration of Sabbath at home and tries to do no work on Saturday. Sometimes we go to synagogue on holidays. Tatiana lights memorial candles in commemoration of our deceased relatives.

Glossary