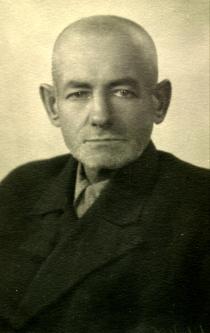

Semyon Ghendler

Ternopol

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: August 2002

When I arrived at his home, Semyon Ghendler wasn't expecting me. I was joined by the chief of the local Hesed. Semyon was planning to go to the polyclinic, but when we came he cancelled his visit to the doctor and agreed to give me an interview. Semyon is tall and still strong man. He is cheerful and has a good sense of humor. When telling his story he smoked a lot. It was exciting for him to remember the past and his loved ones. After the interview, Semyon told me that he hadn't expected the interview process to be so hard. Semyon lives in a two-bedroom apartment in a five-story building that his crew built in the 1960s. He has a set of furniture bought in the 1970s: a living room set, some plain crockery in the cupboard and classical books in the bookcase. Semyon told me there was no furniture in another room: his son took it to the apartment where he lives with his wife. His apartment doesn’t look like any other bachelor’s dwelling. One can tell that Semyon loves living and his sense of humor helps him to cope with it.

Family Background

My paternal grandfather Nuta, or Nathan Ghendler was born in Ovruch Volyn province (Zhytomir region at present, 250 km from Kiev) in the 1860s [in the early 20th century the population of Ovruch constituted about 8 thousand people and half of them were Jewish]. In 1850 Ovruch became the Hasidic 1 center. There was a Hasidic synagogue and a private Jewish school in Ovruch. In the early 20th century Ovruch became the center of Zionist activities. During the Civil War 2 the power in town switched 15 times and there were pogroms 3. The most blood shedding pogrom was arranged by Petliura groups 4 in late 1918 – within 17 days they exterminated about one hundred Jews. Soviet authorities closed the synagogue during the period of struggle against religion 5 in the middle of the 1930s. I don’t know what my grandfather Nuta was doing before the revolution of 1917 6. When I knew him in the 1930s he didn’t work and received a small pension. My grandfather was a strong and tall man with a big gray beard. He always wore a cap and never even sat down to a meal with no headpiece on. My grandfather was religious and prayed every morning with his tallit and tefillin on. On Saturday and Jewish holidays he went to the synagogue with grandmother Feiga. Grandmother Feiga was born in the late 1960s. She was three years younger than my grandfather. She was a small and thin old woman. She wore a kerchief. She had no education whatsoever and was a quiet and taciturn woman. She was a housewife. They lived in a small house with three small rooms and a kitchen. There was a big Russian stove 7 in the kitchen. My grandmother cooked delicious food in it. She baked pies and challah bread for Sabbath. There was a small vegetable garden and a few fruit trees near the house. My grandmother Feiga never went to work. She did housekeeping and raised her children like all Jewish women at the time.

I don’t know exactly how many children Nuta and Feiga had. Some children died in infancy. I know of four children including my father. Froim, the oldest, was born in the late 1890s. Froim became a baker and owned a bakery before 1917. During the Soviet period he was director of a state owned bakery that was later modified into a bread factory. In my childhood my parents and I visited his bakery and he treated us to nice hot rolls. Before the Great Patriotic War 8 Froim, his wife and their sons Osia and Lyova lived in Ovruch. When the Great Patriotic War began their sons were recruited to the army and Froim and his wife evacuated. After the war Froim and his wife moved to Kiev where their older son worked as an engineer. Lyova settled down in Subcarpathia 9 in Uzhhorod [850 km from Kiev] where he worked as chief engineer at the furniture factory. Froim died in the middle of the 1960s. I lost contact with Osia and Lyova’s families. I don’t even know whether they are still living. Froim was raised religious like all Jewish boys, but he was an atheist and didn’t observe Jewish traditions. However, he respected his parents and always attended celebrations of Jewish holidays in my grandfather’s home.

My father also had two sisters, whose names I don’t remember. One of them lived in Ovruch. Her son was named Shloime like me. He perished during the Great Patriotic War. Her daughter Zinaida was a dentist. In the 1970s she moved to Israel with her family. I wasn’t in contact with her after the Great Patriotic War. As for the second sister, who lived in Korosten not far from Ovruch, I only saw her once in my life at a family gathering in my grandfather’s home before the great Patriotic War. During the war she was in evacuation and after the war she lived in Simferopol in the Crimea, 800 km from Kiev. I know that she was married, but I don’t know how many children she had or their names. I never met with my aunt after the war and don’t know when she died.

My father Zachari Ghendler was born in Ovruch in 1904. He received traditional Jewish education: he finished cheder and four years of Jewish elementary school. He knew Yiddish well and he also knew the Torah, but during the Soviet regime he was an atheist. In 1917, during the revolution, my father joined the Red army like many Jewish young people escaping from pogroms and poverty in their towns hoping for a different life. My father served in cavalry. After the Civil War my father was a laborer at different jobs. In 1925, when he met my mother, he was a laborer at the leather factory: he handled skin leather.

My mother came from Zhytomir. Her father Iegoshua Leiba Shlyoma Oks was born in Zhytomir in 1878 and grandmother Esther was born in Zhytomir in 1880. [Editor’s note: Zhytomir is a regional town in Ukraine, 150 km from Kiev. In 1926 its population constituted a little over 100 thousand people and 39% of it was Jewish. Two thirds of all craftsmen in the town were Jewish. Zhytomir was one of historical centers of Hasidism. Before the revolution of 1917 there were few dozens synagogues and a rabbi seminary in the town. After the revolution religious activities gradually decayed and by the early 1930s there was one synagogue operating in the town]. My grandfather finished cheder and went to work. He became a high skilled cabinetmaker. Before the revolution he worked for his employer and after the revolution he went to work for the ‘Bogatyr’ furniture shop that became a furniture factory in the 1930s. My grandfather earned well. After the revolution he manufactured furniture on private orders. My grandfather was very religious. In the 1930s, when I knew him, my grandfather wore a small well-groomed 3-4 days’ growth beard. He also wore a cap or a hat, but I never saw him wearing a kippah. My grandfather always prayed before going to work with his tallit and tefillin on. On Friday, Saturday and Jewish holidays he went to the synagogue. His employers respected him so much that they allowed him to not come to work on Saturday. Instead, he came to work on Sunday to do his portion of work. My grandfather’s portrait was on the board of honor of the factory [Editor’s note: every factory, plant, or any other state enterprise in the Soviet Union had a board of honor with portraits of the best workers of the factory. It was a great honor to have one’s portrait there]. Grandmother Esther was a housewife. She always dusted their tiny apartment. They lived in two rooms and had a kitchen, but when their children grew up and moved out they had a tenant in one room. I loved visiting my grandfather and grandmother and remember their room very well. They had a beautiful carved cupboard that grandfather made himself, a wardrobe and chairs with high carved backs. There were snow white napkins on the cupboard that my grandmother made and seven little elephants: a symbol of happiness at the time. I knew only one grandfather’s brother named Moishe. He was a jeweler in Zhytomir. I saw him several times. He was a presentable man with a beard. Moishe died shortly before the Great Patriotic War. I know nothing about his children Zachar and Rachil. I don’t know whether my grandfather had other brothers or sisters and I have no information about my grandmother’s family either.

My grandparents had three children: my mother and two brothers, one older than my mother and one younger. My mother’s brothers finished cheder. They grew up to be atheists. In the 1930s they joined the Communist Party. Aron, the older brother, born in 1902, dealt in trade. He was married, but divorced his wife. From Zhytomir Aron moved to Fastov where he worked at the railway station of Grebyonki and later in Nezhin. During the great Patriotic War Aron was in evacuation somewhere in the Urals. His second wife’s name was Olga, she was Russian. They didn’t have any children. After the war Aron and Olga returned to Nezhin where Aron died in the middle 1960s.

My mother’s younger brother Lazar was born in 1908. Lazar finished Kiev Engineering Construction College and worked as an engineer in Dnepropetrovsk, 350 km from Kiev. His wife was Russian. I don’t remember her name. Their daughter had a strange name of Saida. We called her Saya. During the great Patriotic War Lazar served in an engineering unit building bridges and fortifications for frontline forces. After the war he returned to Dnepropetrovsk. Lazar died in the early 1970s. His daughter Saida and her family live in Dnepropetrovsk.

My mother Yelizaveta Ghendler (nee Oks) was a withdrawn person. I know little about her life before marriage. She was born in Zhytomir in 1905. At home she was called Lyonia for some reason. Though her parents were religious they decided to give their daughter secular education. My mother finished a Russian grammar school in 1918. I don’t know whether my mother worked before the early 1920s, when she met my father. They met in 1925 and fell in love with one another. My father was a strong handsome man. My mother was young and fair-haired. They made a beautiful match, but they couldn’t get married right away. My grandparents Oks were against their marriage. They believed my mother could find a better match with education equal to her own, but my mother wouldn’t even consider another man. In 1926 my mother’s parents gave up and my parents got married. I don’t know any details about their wedding. All I know is that it was a traditional Jewish wedding. The young couple was so happy to have their parents’ consent that they didn’t argue about having a chuppah, and rabbi and a marriage contract, though by this time they had given up religion. They had a traditional wedding in Zhytomir where they invited relatives from Ovruch and Korosten and then my parents had a civil ceremony in a registry office.

My parents settled down with distant relatives on my mother’s side. I guess, my mother’s parents didn’t quite approve of their daughter’s misalliance, as they thought of it. My parents lived their first years together in a small room in a long building. I was born on 8 November 1927. I was named Shlyoma, but later I changed this name to the Russian name 10 of Semyon for convenience.

Growing Up

I have some memories of my childhood. I remember visiting my maternal grandfather and grandmother at Chanukkah. Of course, I learned the name of the holiday later, but I remember delicious doughnuts that my grandmother made and I also received some money from them. My grandmother made delicious pastries and the biggest offence for her was when somebody told her that they had eaten more delicious doughnuts. My grandfather took me to the synagogue: a big two-storied building in the center of Zhytomir. When my grandmother went with us she went upstairs and my grandfather and I stayed downstairs. We often visited my father’s parents in Ovruch. I remember the first Pesach in my life that we celebrated in their house. My father’s relatives got together on this holiday and his sister came from Korosten. There was a table beautifully set for dinner. My grandfather was reclining on two cushions with his back to the door. I was to find a piece of matzah that he hid under a cushion. There was a lot of laughter and comments while I was looking for it. Then my grandfather conducted seder and I posed four questions to him about the nature of this holiday and my father helped me. I think I have such bright memories about these celebrations since they were unusual for me. We didn’t observe Jewish traditions in our family, though my mother or father never joined Komsomol 11 or the party, but they were atheists. In the early 1930s we lived in Olevsk of Zhytomir region, 70 km from Zhytomir. My father was offered to work in a store and the family moved to this town. We lived with some relatives in a wooden house with a garret. I have dim memories of famine in 1932-33 12, when my father brought some packages from his work. This was dried bread that we dipped in water before eating them. I remember a constant feeling of hunger, but nobody died in our family, though there were dead people in the streets every morning and special trucks picked them. We stayed in Olevsk less than a year. My father proved to be good in trading business. Although he didn’t have any special education he was offered to become director of a fish store and in 1935 he got an offer to become director of a big food store in Zhytomir. We returned to Zhytomir.

We got an apartment in Zhytomir. In 1935 my mother gave birth to my sister, named Polina. That same year I went to a Russian school. My parents didn’t even discuss my going to a Jewish school. We spoke Russian in the family. My parents rarely switched to Yiddish when they didn’t want me to understand the subject of their discussions. My grandfather still took me to the synagogue on Saturday, but I lost interest in it. I ran away from him until my mother told him to stop taking me with him. I preferred to spend time playing with my friends. There were Russian, Ukrainian and Polish children among my friends. Nationality didn’t matter. We spoke Russian and enjoyed spending time together. There were few Jewish families among our neighbors. They didn’t observe any Jewish traditions either. A Jewish family lived in a small house in the middle of our yard. The father was chairman of the regional consumer association. His last name was Shames. His son Betia was my friend. Our neighbor, doctor Shapiro, was a Jew. He was a member of the party and deputy of the town council.

We lived in a small apartment. There were two rooms and a small kitchen. I remember the furniture that my father bought: big nickel-plated beds and a wardrobe. The table was always covered with a fancy tablecloth and there were linen covers on the chairs and the sofa. My father had an average income sufficient to make a decent living. My mother didn’t work before the Great Patriotic War.

My friends and I played war and pirate games and football. We often went fishing to the Teterev River. There were picturesque spots in the area: I can still remember the smell of newly mown hay and meadow herbs. On weekends my parents and I went to the riverbank. My father went swimming and my mother was waiting on the bank looking at him. They enjoyed talking to one another and my sister and I joined our friends. Another boys’ hobby was keeping pigeons. My father made a pigeon house in the yard and we spent there all our spare time.

I had many friends of various nationalities at school. There was no such issue as nationality before the war. I studied well and was fond of mathematic and physics. I also liked geography. My pioneer errand was issuance of a wall newspaper where I was an editor. I visited my grandfather in Ovruch on my summer vacations. I also spent my vacations in a pioneer camp on the Teterev River. We celebrated Soviet holidays at school: there were pioneer marches on 1 May and 7 November 13, and on the international Day of young people on 1 September. We always went to parades on holidays. It was a lot of fun. We also celebrated Soviet holidays at home. My parents invited their friends. They danced to the wireless and sang Soviet songs. The only reminder of Jewish traditions was matzah that my grandfather always brought at Pesach. At Pesach and Rosh Hashanah we visited my grandfather where they had family gatherings or went to visit my father’s parents in Ovruch. The family discussed family news and enjoyed getting together. My grandparents understood that the generation of my parents was not religious and didn’t say prayers in their presence.

The Great Terror

When in the late 1930s arrests began [Great Terror] 14, my father had a fear of being arrested, even though he wasn’t a party member. Many of his friends and acquaintances holding key positions were arrested. I think my father understood that it was despotism, but my parents didn't have any discussions in my presence. There was the feeling of alarm in our house like in many others. I remember that some time in 1938 the doorbell rang late at night. My father asked who it was before opening the door. It was a stranger. His surname was Litvak and he was a Jew. My parents took him to the kitchen, gave him some food and money and he left. From their words I understood that this man escaped from his hometown in fear of arrest and visited my father as his old acquaintance. I don’t know what happened to him then. After this visit my father had many sleepless nights fearing arrest. If somebody saw our late visitor they would have reported and my father would have been arrested for giving shelter to an ‘enemy of the people’ 15. My mother prepared a bag with underwear and dried bread for my father. This bag was in a corner in the kitchen for a long time. Fortunately, nothing of the kind happened in our family.

During the War

On 22 June 1941 my friend Beba Shames and I were to go to a pioneer camp. At 12 o’clock we listened to Molotov 16 on the radio. He said that the Great Patriotic War began. On 24 June 1941 my father volunteered to the army. Two days later we received a subpoena for him to make an appearance at the military registry office. So, he would have been recruited anyways. Some time later we received a letter from my father from somewhere near Lvov. Shortly afterward he came home during the retreat of our troops. I can still remember him in his uniform, having a gun. He was an officer. This was on 4 July 1941. My father washed and helped my mother to pack and then we went to the railway station on a truck waiting for us. My father took us to the station where we boarded a train heading to the East. My father kissed us and then stood with my mother on the platform for a long while. I even felt hurt that he spent so much time with her saying such a short ‘good bye’ to us. He hugged and kissed her. I didn’t know then that I was seeing him for the last time.

It took us four days to get to Kharkov, about 450 km away. In Kharkov we stayed with our distant relatives for about a month. Everybody still believed that the war was to be over soon and we would return home. In early August grandfather Iegoshua and grandmother Esther came to Kharkov. German troops were near Zhytomir. We moved on to the East. Our trip lasted for about a month and a half. When the train stopped we exchanged what we had with us for food. I remember exchanging a bar of soap for a carrot that I brought in my cap to the railcar. I was very proud of myself. At times we got a hot meal at stations, but most often it was some boiling water. We arrived in Cheliabinsk in the Ural, 1500 kilometers from our home. Cheliabinsk was a big industrial town. There were many plants in the town and many enterprises evacuated from the western part of the country. We stayed in the evacuation agency few days until we were accommodated in a barrack with other families. It was a wooden barrack with plywood or curtain partitions. My mother, my sister and I and my grandfather Iegoshua and my grandmother Esther lived in one of these small rooms several days until uncle Aron who came to Cheliabinsk after we did went to work at a big plant and received a room. He was manager of metal stocks at the plant.

Our life was gradually setting up. My grandfather went to work as a carpenter in the “Cheliabstroi” construction company. My grandfather got along well with his colleagues. My grandfather and grandmother tried to observe Jewish traditions. There was no synagogue in Cheliabinsk and my grandfather prayed in a corner of our room twice a day. My grandfather didn’t go to work on Saturday. He discussed this condition before getting this employment and his management showed understanding of his requirement. There was a hospital near our barrack and my mother went to work there as a logistics attendant. She received a room in the hospital and my mother, my sister and I went to live there. I went to the 7th grade at school. My sister stayed at home. Early in the morning I went to stand in line to buy bread. There were bread cards to get rationed bread and there was always too little of it.

We received only one letter from my father in September 1941. He wrote us from near Kiev. We didn’t have any information about his parents, grandmother Feiga and grandfather Nuta Ghendler. My mother often cried at night. I felt responsible for my mother and sister being the only man in the family. I took no interest in studies. Thought I had learned all that I needed. I wanted to go to work to support my mother. I talked with my mother and she helped me to become an apprentice of a joiner at a military plant. I was very proud to be going to work every morning. I also received a food card that was sufficient support to our family. I smoked a lot and was very glad to receive a pack of tobacco once a month like an adult man. I worked for almost a year until I went to study at the factory vocational school in 1943. I was to become an electrician. After finishing this school I received my certificate of secondary education and went to work as an electrician at the Cheliabinsk tractor plant. I also could live in a hostel. I made friends with other workers who were older than me. We used to have a drink every now and then and I began to meet with girls. My mother didn’t like this at all. She still believed I was a child. We often argued and once I didn’t see my mother for two or three months. It was 1944 and Zhytomir was liberated. Once I bumped into a man from Zhytomir and he was surprised to see me in Cheliabinsk. It turned out that my mother, my sister, my grandfather and grandmother had left for Zhytomir. I felt so hurt that tears came into my eyes. I still don’t know why they were so cruel to me. My mother told me later that she wanted to teach me a lesson, but I still believe it was unjust. When I got to know that my family had left I left the town as well. I didn’t quit officially and had no documents with me. I climbed the roof of a railcar to go to my Motherland. I didn’t have a permit for reevacuation or any other document. It took me a long time to get to my town. Conductors caught me and told me to get off the train and then militia caught me as well. I ran away from militia and other militiamen helped me to get on another train when they heard my story. Then finally I arrived at Zhytomir almost three weeks later.

In Zhytomir I only found my grandfather and grandmother who lived in their apartment. My mother and sister were visiting their acquaintances in Kazan. There were other tenants in our apartment and there were no belongings of ours left. Our Polish neighbors Ignatovich took our most valuable belongings: the “Singer” sewing machine, bed sheets and some crockery. They were keeping them for us. They also gave me shelter. Then my mother arrived. It’s hard to describe how we met. We were both crying asking each other forgiveness. The Ignatoviches gave us one room in their apartment. They also made a door in the room. My mother didn’t want to go to court to get back our apartment. We couldn’t get any information about my father for a long time. My mother wrote letters to various organization, but their only response was: ‘His surname is not in the lists of deceased or missing’. Few days later a man from Zhytomir, my father’s fellow comrade, told us that my father perished near Kanev in 100 km from Kiev, and was buried in a common grave with writer Arkadiy Gaidar 17. In the 1960s my sister and I visited Kanev. We found the grave where according to what this man told us my father was buried in Kanev. This grave in on a steep bank over the Dnieper.

In 1944, when we returned to Zhytomir, we had to think about how to survive. My mother learned to type in Cheliabinsk. She went to work as a typist in an office. My sister went to school. My father’s brother told us that grandfather Nuta and grandmother Feiga were killed with other Jews of Ovruch in late August 1941.

In late 1944 I received a subpoena to the army. I went to serve in the Navy. In early January 1945 we boarded a train to the Far East in Zhytomir. At first I was a ship’s boy and then became a sailor on the ‘Kalinin’ cruiser. I participated in the war with Japan 18. In 1945 our cruiser transported Soviet landing troops to Korea. I served 7 years in the navy: this was a standard term in those years. Although service in the navy is hard I enjoy recalling this time. Firstly, I ate heartily for the first time in my life. We got sufficient food. They gave us American tinned meat. What else would a young man want: rich food and good friends. I had many friends. There was another Jewish Navy man on our boat and we never faced any prejudiced or abusive attitudes. We were all equal. In the evening we played chess, read and went on a leave together. I cannot say anything about open state anti-Semitism in the late 1940s –early 1950s. We had political classes, but our officers managed to avoid any issues related to anti-Semitic campaigns. In 1947 I received a letter saying that grandmother Esther died. She suffered from a mental illness for few years. My grandfather died in 1963. They were buried in the Jewish section of the town cemetery in Zhytomir. I don’t know whether anybody recited the Kaddish for them.

After the War

In late 1952 I demobilized and returned to Zhytomir. This was the period of the Doctors’ Plot 19. For me this anti-Semitic propaganda in newspapers was terrible. Shortly afterward, in March 1953 Stalin died. I grieved after him sincerely. I attended a mourning meeting in the center of Zhytomir with other towns folks. I never related Stalin’s name to the horrors of what was happening around. I was too young to analyze.

I worked as an electrician for few months. At that time I met my wife to be, a girl, and we fell in love with each other. Natalia Danilyuk, nee Kuznetsova, had already been married. She had divorced before we met. She was born in Zhytomir in 1929. Her father who was Russian perished during the great Patriotic War. Her mother was a Jew named Sheina. Natalia and her mother lived in a very small room. I knew I needed to have a place to live with my family. There were no perspectives in Zhytomir in this regard and in spring 1953 moved to Cheliabinsk writing my friends there. It was easier to find a job in Cheliabinsk. I went to work as a construction electrician at the Cheliabinsk metallurgical plant. Later I became a foreman, site manager and then was promoted to assistant manager of the ventilation shop. I had many friends. They were workers of various nationalities and we got along well. Only once I was abused. It happened at the very beginning of my career in Cheliabinsk. On a payday members of my crew were waiting for their turn to receive salary. I joined them later and then one guy from the line said: ‘Get out of here, stand in line and forget your zhydovskiye [Russian offensive for Jewish] tricks’. My friends said to me: ‘Semyon, if you let him go you are a weak man and a ninny and we are not your friends’. We waited for the guy at the entrance check point and I beat him up.

I received a room in a hostel. Natalia came to live with me and in summer 1953 we got married. We had a civil ceremony in a registry office. Natalia went to work as a shop assistant at a baker’s shop. In 1954 Alexandr was born. We received a one-bedroom apartment. 12 years later, in 1966, our twins Georgi and Zhanna were born. We began to consider moving to Ukraine where our mothers were living and climate was pleasant and ripe apples and apricots were falling onto the ground. Fruit and vegetables were expensive in Cheliabinsk and besides, we were homesick. In 1967 I sent a job request to Vinnitsa construction department. They sent their response with a job offer. I already had a reputation in my branch of industry. When I came there to be employed their manager seeing that I didn’t have special education, was a Jew and was no member of the party refused to employ me. A man from a higher level organization came to my help. He knew my qualifications and said that my qualification was rolling mill 2300, tube mill in Cheliabinsk that I constructed was better than any college education and then I got employment. My job was construction of a roll bearing plant in Vinnitsa. This site was in a poor condition when I came to work, but then I handled it and we became one of the best sites. My wife and children were waiting in Cheliabinsk. It was difficult to get an apartment in Vinnitsa and I decided to go back to Cheliabinsk where we at least had an apartment, but this time my manager didn’t want to let me go. He assigned me site manager of a construction site in Western Ukraine, 370 km from Kiev, in Ternopol. It was construction of a big cotton factory. I received a room in a communal apartment 20. My family joined me and there were five of us living in one room. I went to talk with first secretary of the regional Party committee and told him that if they didn’t give me an apartment I would go back to Cheliabinsk where they would be glad to have me. First secretary ordered me to complete construction of a school within two weeks and if I managed he promised to give me an apartment. I went back to talk to my crew. When they heard what it was about they worked day and night to complete this construction. In August 1968 I received a two-bedroom apartment. This is where I live now. Later I finished the extramural department of Construction College in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Some time later my wife’s mother Sheina moved to Ternopol. She lived separately from us. Sheina was religious, and she celebrated Pesach and we visited her at her request. We didn’t observe any traditions or celebrate Jewish holidays in our family.

We had many friends. We celebrated 1 May and 7 November. My crew members and I came to my place after parades. Natalia cooked and we had parties. We often had outings with shashlyk [barbecue]. In summer we took our children to the seashore and when they grew older we sent them to a pioneer camp and spent vacations together, just the two of us. When the time came for our children to identify their nationality they chose to be Russian and adopt my wife father’s surname of Danilyuk. I understood it would make it easier for them to get education and make a career this way. I loved my wife dearly. Before retiring in the middle of the 1980s I decided to make some money for our old age. I went to the construction of an oil pipeline in Tumen in 3000 km east from home. They paid very well for work. I lived in a tent. Living and climatic conditions there were very hard. My wife fell ill and in late 1987 I returned to Ternopol. Natalia had cancer. In late 1989 she died. I went back to the north after she was buried and worked there sometime longer. I cannot forget my wife. She was the only woman I loved in my life. Since then I’ve been alone.

After finishing school my sister Polina finished mechanical school in Zhytomir. There she met her future husband Vladimir Lukashevich. Vladimir is a half-breed like my wife. His father was Russian and his mother was Jewish. He finished a military school and was sent to Rybinsk in Moldova. Their daughter Irina was born in Rybinsk. My mother went to my sister to help her raise her daughter. Few years later Polina’s son Sergei was born. Both children received education. Sergei finished a technical school and Irina finished a precious metal vocational school in Kiev. Sergei and Irina have families. In the early 1990s my sister, her husband and their children moved to Israel. Her husband died in Israel. My sister lives with her daughter in Haifa. I correspond with her.

My mother was alone for many years. In the middle of 1960s she married our distant relative Isaac Zhuravski. I was glad that my mother was not alone any longer. Living in Cheliabinsk I couldn’t support her. However, their marriage lasted less than a year: Isaac was pathologically greedy and my mother divorced him. She lived in Zhytomir until 1990. When I returned from the North she moved in with me here. She remained an atheist even at her old age. She didn’t observe Jewish traditions. She died in 1992. She was buried in the town cemetery and there were no rituals observed at her funeral.

My older son Alexandr graduated from the State University in Perm. He is an economist. During perestroika 21 Alexandr finished college and became a high skilled expert in stocks. Alexandr lives in Kirov in Russia, 800 km from Moscow. My son is different from me in his marital life. He has a third wife now. I don’t know them. Alexandr rarely comes to see me and he always comes alone. His sons from the first marriage Leonid, born in 1976, and Maxim, born in 1978, do not communicate with him or me.

My daughter Zhanna married Victor Shanenkov, Russian, after finishing school. He was on service in Ternopol. He came from Dzhambul in Kazakhstan. When his term of service was over Zhanna followed him to Dzhambul in 3000 km from home. Their marriage failed. In 1989 Victor left for Greece leaving his wife and daughter Alina at home. Zhanna married a civil pilot, but it didn’t work either. He was fired from work for drinking. He became a drunkard and disappeared. Zhanna had a daughter from him named Natalia after my wife. Zhanna lives in Dzhambul. She works as a secretary in a company. Natalia finished school and entered Medical College in Velikiy Novgorod where her grandmother, Victor’s wife, lives. To his honor I need to mention that Victor supports Zhanna and Natalia.

My younger son Georgi entered Odessa artillery school after finishing secondary school. After finishing it he served in Poland. When out troops were leaving Eastern Europe in the 1990s he retired from the army. His first wife was Bulgarian. Georgi divorced her. She left their son David with her mother and went to work in Poland. We don’t know where David is now. Georgi married a woman with a child. She is Russian. Her daughter Kristina gets along well with Georgi and with me. She calls me ‘grandfather’. I treat her as my granddaughter and at Chanukkah I always give her some money as customary with Jewish families.

I had a good life. I had many friends wherever I was. The huge Soviet Union was my home and I feel bad about the breakup 22 of the country. I still have friends in Cheliabinsk, Tumen and other towns. They often call me, even at night, due to the time difference. However, I feel sad about not being able to visit them like I used to when we might come all of a sudden without notification. We often went with families to Odessa, the Crimea or Caucasus. We cannot afford this now. In the past my monthly salary was enough to buy plane tickets and stay in any town of the USSR for a couple of weeks with my family and now I have to think twice even about commuting in the town. A ticket to the nearest town costs half of my pension, not to mention planes. All my savings that I earned so hard working in the north were gone when perestroika began. My sons support me and I try to support my daughter. The only positive thing that I see in perestroika is democracy for minorities, including Jews. I am a member of the Jewish community in Ternopol. Of course, I shall never become religious, but I like studying Yiddish, Jewish traditions and celebrating Jewish holidays in the community. The local Hesed provides assistance to pensioners. I’ve been to Israel. I admired this country. It was built with love, but I understood that I would never be able to live there. It’s a different country for me with a different life style and hard climate. I couldn’t wait until my month’s long visit to my sister was over and I could return to Ternopol.

Glossary: