Sarra Shylman

Ukraine

Kiev

Interviewer — Inna Zlotnik

Date of interview: September 2003

Sarra Shylman lives in a two-bedroom apartment with all comforts in a 9-storied building in Kharkovskoye shosse in a new district of Kiev in some distance from the center of the city. The Shylman family received this apartment in 1963, after their house in the center of the city where they had lived for about 40 years was pulled down. Sarra is a short slim woman with attentive gray eyes and gray hair cut short. She has a fancy blouse on. She made it herself. She’s always made her own clothes. There is asset of furniture of 1960s in her room. There are many books by Russian and foreign classics, but there are also books by modern Jewish authors. 3 years ago her husband Yefim Shyfris died. They lived together for almost 50 years and now books and family albums help her to cope with her loneliness. Sarra has a hearing problem and she's had a stroke recently, but she is energetic and reads a lot. She is interested in Jewish life. She enjoys telling me the past and present history of her family, even though it hurts: many of her dear ones are gone.

It happened so that she has no relatives left with her. Now she can only look at their photographs in her album. She has acquaintances in Kiev. They often call her. Sarra Davidovna lives on her pension and Hesed provides food packages to her. Before her husband passed away they often celebrated Jewish holidays at Hesed, but she does not go there any longer. She is too weak for that. She celebrates Jewish holidays at home now. She always lights candles on Friday like her mother did on those far away days.

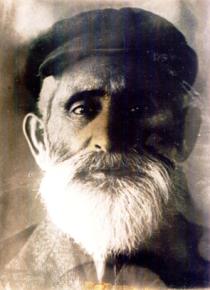

I want to tell you about my dearest ones: the Shylman family. My paternal grandfather Itzyk Shylman was born in Belopolie town Berdichev district in 200 km from Kiev in 1840s. He was a teacher at cheder and his surname Shylman means ‘school man’ in Yiddish. The majority of population in Belopolie was Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish. Jews sold agricultural products and were shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, blacksmiths and leather specialists.

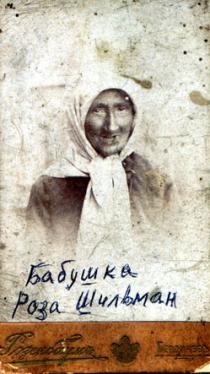

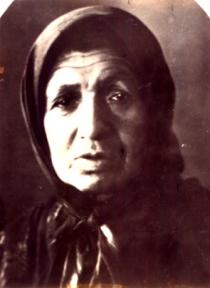

My grandmother Rosa Shylman was also born in Belopolie in 1840s. She was a housewife as customary in Jewish families. My grandparents had 9 children: eight sons and one daughter. I don’t know the names of my father’s older brothers. There was a great difference in age between them. My father’s sister Leika was about five years older than my father. She was looking after him and they were very close during their lifetime. My father Duvid Shylman was born in 1888 and was the youngest in the family. They were a poor family and they didn’t have baby food for the baby. They wrapped bead in a cloth and gave it to the baby as a baby soother. My father told me that their family was very religious: there was Torah in the house, his father prayed and his mother lit candles on Friday. The family sat down to the table and although there was plain food they always celebrated Sabbath according to the rules. My father recalled how he and his brothers and their parents dressed up to go to the synagogue on Saturday. Grandmother Rosa made clothes for older boys and the younger sons wore their older brothers’ clothes after they grew out of it. Though the family had little to live on they always celebrated Pesach, Purim, Chanukkah and other religious holidays according to traditions. Rosa was a good housewife: she had a big vegetable garden and kept chickens. Her children always had clothes to wear and food to eat. Grandfather Itzyk died of some disease in early 1900s. My father hadn’t finished cheder by then. My grandmother Rosa had some education. She could count well and after my grandfather died she went to work as an exchange agent at the market. When somebody needed to count money or get smaller change my grandmother was always at hand. She did these operations for a small fee. She was well respected in her town. My father told me that she was cheerful and energetic and always wore a kerchief, as was a custom with Jewish women.

All boys finished cheder in Belopolie, but they didn’t continue their education. Older brothers moved to America in the early 20th century. My father didn’t correspond with them since our country people couldn’t acknowledge having relatives abroad [1]. They were never mentioned in our family and I don’t even know their names. Aunt Leika corresponded with them, but she perished during Holocaust and took with her everything she knew about them.

In early 1900s Leika married Gershl Vagner, a Jewish man, that she met through matchmakers. They lived in Maly Ostrozhok village Vinnitsa district, in 220 km from Kiev. I often visited them in my childhood and I remember their pise-walled hut with thatched roof. There was one big room in the hut where Leika, Gersh and their five children: four boys and one girl. Aunt Leika’s daughter was five years older than I. She was born about 1925, but I didn’t know her. She died in infancy. The older son’s name was Srul, but all acquaintances called him with the Russian name of Sergei [common name] [2]. When Leika’s son died in 1920s Srul went to work in a kolkhoz to support the family. His younger brothers Meyer and David finished a school in Maly Ostrozhok. Thanks to Srul’s support they could continue their education. Mayer finished a Pedagogical College in Berdichev. There was lack of specialists and he was appointed director of school in a village. David finished a Pedagogical College in Berdichev before the war and was appointed director of school in Lurintsi village of Vinnitsa region.

Once Srul was transporting grain and one bag fell from the wagon and was lost and Srul was accused of theft. He was sentenced to exile in Nagaevo bay in the Far East, in 7000 km from home. This happened in 1937– 38 [Great Terror] [3], when many innocent people suffered. During the Great Patriotic War [4] he was in imprisonment in the Far East. When in 1945 the Japanese War [5] began he was sent to the front with a penal company and perished.

His brothers Meyer and David got married before the war. Meyer married a Jewish woman and David married a Ukrainian woman. Their sons had the same name of Grigori after grandfather Gershl: these names sound alike. David and Meyer were in occupation and in 1941 they came to their mother Leika in Maly Ostrozhok. Their neighbors gave them away to Germans and before aunt Leika’s eyes her grandchildren (sons of Meyer and Srul) and then David and Meyer were killed. It happened near her house.

Leika’s younger son Sergei [Srul] was born in 1919. Before the Great Patriotic War he studied in the military infantry school in Dniprodzerzhynsk, and when the war began he went to the front in the rank of lieutenant. In 1942 was severely wounded and taken to hospital. After he was released he returned to the front. In 1948 he was sent to the Far East. He was promoted to the rank of colonel, retired and moved to Leningrad to his cousin brother Leonid Medved. Sergei worked at a big plant and held a big position. I don’t remember anything about his family. All I remember is that Sergei died in Leningrad in 1979 on the 61st year of his life.

Perhaps, David’s son Grigori Vagner, born around 1937–39, survived. I hope that his Ukrainian mother manager to rescue him during the Holocaust. I once read in the ‘Yevreiskie Vesti’ [‘Jewish News’, issued by the Jewish council of Ukraine, established in 1992] a story by Grigori Vagner borrowed from an Israeli newspaper. Perhaps, Grigori Davidovich Vagner, my nephew, lives in Israel? I hope he will read this interview and find me, if it is him.

My mother Ghitlia Shylman was also born in Belopolie in 1893. My mother’s father Moisha-Alter Yablochnik was also born in Belopolie in 1860s. He rented apple orchards. He was a good specialist in apple trees. He could determine, which orchard would give good harvest. He rented such orchards and then sold apples. The surname of Yablochnik derived from the word ‘yablonia’ [apple tree]. I cannot say for sure, but I think that my grandfather’s ancestors may have received this surname in connection with their profession. Alter is ‘old’ in Yiddish. He had this name because he got married at an old age.

My maternal grandmother Surah-Leya Yablochnik, was born in Belopolie in early 1870s. My grandparents had five children. Their older son (I can’t remember what his name was) died in an accident in his infancy. A horse-driven cart riding fast down a hill rode over him. My mother Ghitlia Yablochnik was born in 1893. There were 3 sisters born after my mother: Basia was 2 years younger than my mother, Sonia, born in 1898, and Fania, the youngest, born in 1900. My grandmother Surah-Leya kept the house and was a vendor and my mother looked after the children. My mother was very crafted: she liked knitting and embroidery. All girls helped grandmother Surah-Leya in the garden and orchard. My mother told me that they spoke Yiddish in the family. My grandmother and grandfather were very religious: they followed kashrut, celebrated Pesach, Purim, Canukkah and fasted at Yom Kippur.

I remember my grandfather well. He was tall, handsome and kind. He always wore a black yarmulka. My grandmother Surah-Leya died in 1910s and my grandfather married a Jewish woman from Belopolie. Basia got married and moved to Berdichev with her husband and Sonia stayed in Belopolie after she got married. My mother and her sister Fania stayed in their parents’ home. Shortly after the revolution of 1917 [6] my grandfather and my mother’s stepmother moved to Kiev. They lived in Stalinka district. It almost in the center of the city now, while at that time It was its outskirts. I visited them several times, but I don’t remember anything about their house. My grandfather took me onto his lap and was eager to teach me Hebrew. I was a naughty girl. I didn’t stay with him long. So, never learned Hebrew and I am sorry about it. My grandfather and his wife had a daughter. Her name was Busha, but I’ve forgotten the stepmother’s name. My grandfather was very religious. He went to the synagogue in Podol [7] every day. There used to be a synagogue near their house in Stalinka, but in 1920s during the struggle of Soviet authorities against religion [8] it was closed. My grandfather collected clothes and money for needy Jews.

My father didn’t get any education. He was a laborer in Belopolie and then constructed roads in Berdichev. Shortly before the revolution of 1917 he met my mother and in 1918 my parents got married. My mother told me they had a chuppah and there were klezmer musicians playing at their wedding. Shortly after their wedding my parents moved to Kiev from Belopolie. They rented an apartment in Podol. My father was a worker. Replaced pavements. My mother was a housewife. My mother’s sister Fania got married few years after the revolution and also moved to Kiev with her husband.

In summer 1919 my older brother Boris Shylman was born. I was was born on 13 March 1921 and my sister Golda Shylman was born on 23 January 1923. We spoke Yiddish at home. My mother knitted stockings on a stocking machine that had probably 1000 needles. She sold stockings at the market.

Later my father went to work as a clerk at a plant. I don’t know how he managed to get this job, but I think that maybe his proletarian roots and that he could write and read played a decisive role. The plant constructed an apartment house for its employees and my father received a three-bedroom apartment in the center of Kiev not far from the plant. There was a soap factory near our house. We lived in a two-storied house: there was a ground floor and we lived on the first floor. Our apartment had 30 square meters. There were no comforts. My sister and I had a very small room. We slept in a small metal bed. We were growing up and once I said ‘Mother! I shall suffocate because of her and my parents hurried to buy a folding bed and Golda began to sleep on this bed. My brother also had a small room, but I don’t remember what there was in this room. Our parents slept on a big metal bed in the biggest room. There was a table covered with a big tablecloth with fringe in the middle of the room and four chairs round the table. I remember how we sat at this table on Jewish holidays. My father was very religious then. At Pesach my mother took fancy crockery from an entresol. She covered the table with a white tablecloth and put delicious food on it. My father sat at the head of the table and we had seder. I loved Purim. It coincided with my birthday on 13 March. I remember my father turning a chicken over the head at Yom Kippur. This is all I remember. I was too young and cannot remember any details. I don’t know what influenced my father, perhaps, this happened due to general historical tendencies when many young people, particularly workers at plants and factories, got overwhelmed with revolutionary ideas. In 1925 he became a communist and we stopped celebrating Jewish holidays at home. We began to celebrate Soviet holidays: 1 May, October revolution Day [9].

There was a number of houses in our yard. I was small when we moved into this house. When I came into the yard for the first time children asked me my name and I replied ‘Syulia’. I couldn’t pronounce almost half of the ABC. My former neighbors still call me Syulia. There were many Russian children in our yard. My sister Golda understood that Golda was a Jewish name and she stated once ‘I want to be Olia’. She told everybody in the yard that she was Olia. All acquaintances and neighbors began to call her Olia and then we began to call her Olia as well. When at the age of 16 she was receiving her passport she had her new Russian name indicated in her passport. She already got used to be called Olia and had forgotten her Jewish name. My sister made a vegetable garden in our yard and worked there. There was a market across the street from our yard. My mother went there to buy food products. I remember plentiful counters with colorful fruit and vegetables.

I went to a kindergarten as a child. It was difficult to get into a kindergarten in those years. Since I had bronchial asthma and needed special food they sent me to a kindergarten as an ill child. My sister and brother got no opportunity to get permission to go to the kindergarten. It was a Jewish kindergarten. I was too small and my brother and sister and other children from our yard took me to the kindergarten. We spoke Yiddish, sang Jewish songs, and recited Jewish poems in this kindergarten. I particularly liked verses by Lev Kvitko [10]. There was a bookstand not far from our house and my father bought me children’s books. I remember how they smelled, but I’ve forgotten in what language they were. We didn’t have books by Jewish authors at home, but I remember a collection of poems by Shevchenko [11].

After the kindergarten I went to a Jewish lower secondary school. It was a policy then that children were to study in their national schools. Admission to my school required that I passed an interview. I knew Yiddish and my admission was positively resolved. When it was time for Olia to go to school she went to the interview in the Jewish school and said there in Yiddish ‘I don’t speak Yiddish’. She had Russian friends in the yard and didn’t want to go to the Jewish school, but they admitted her anyway. My brother Boris studied in a Ukrainian school. That order about national schools was issued after he went to school. He finished his school in 1936 and entered Kiev Polytechnic College.

I remember the subjects that we learned at school: Yiddish, Russian, Russian literature, mathematics, geography and history. I don’t think we studied Ukrainian. We read books by Jewish authors in Yiddish: Sholem Alechem [12] and others. I can still read in Yiddish. We had a library at school. I remember I liked Gaidar novels [13]. I read his ‘School’ in Yiddish and then in Russian. At the end of each academic year we passed exams. When we became pioneers we often had meetings and I was a secretary at meetings.

I had bronchial asthma since childhood and doctors advised me to spend more time in a village breathing in field and river bank air. When I turned 10 I spent my summer vacations in the village with my aunt Leika. She had a cow and I had delicious fresh milk. I remember that during famine in 1933 [14] my parents sent bread to aunt Leika from Kiev. She worked in a kolkhoz, but they starved anyway. Her brothers sent Leika white flour from America. Aunt Leika loved me a lot: she made me flat cookies from this flour and I had cookies with milk. She tried to save me from hunger, but they starved. By that tie Leika’s sons lived separately. I spent summers with my aunt Leika 5 years in a row and when I turned 15 I actually recovered. I believe people in Kiev also starved. When I returned to Kiev I remember long lines for bread. There was a store near our house and I remember how my mother and I stood in lines there.

After we finished this lower secondary school our teachers advised our parents to allow us to continue our education in the Jewish high school, but I didn’t want to go there. I was 15 years old. I took my documents and submitted them to Russian school #15 in Pushkinskaya Street. I was fluent in Russian and it wasn’t a problem for me to study in a Russian school. I was successful at school and got along well with my classmates and teachers.

I was a favorite daughter. I was interested in everything and I studied well. In 1939 after finishing school I entered Kiev technological College of Silicates. Before the Great Patriotic War our situation improved and my parents bought me a desk, a wardrobe and a sewing machine. My college was an affiliate of the Polytechnic College. I entered there without any problems. Jewish origin was no obstacle at admission. I liked mathematics and had a good knowledge of it. I got along well with our teachers and students regardless of my name Sarra [Jewish names were targets of mockery, vulgar jokes and often exclusion at the time.]. I had excellent marks in my college: I had an excellent knowledge of chemistry, physics and mathematic. I wasn’t a Komsomol member [15], but I was an activist and I lectured to students. I remember I prepared a lecture ‘Physical occurrences from the point of view of electronic theory’ to our students.

My sister decided that since I studied in college it became a must for her to enter college too. Se entered an evening department of the Polytechnic College. I received a stipend and Olia wanted to be as good and I and went to work. There was a military special school and she went to work as a lab assistant in this school.

In 1939 Hitler started a war in Europe. Before the war we heard rumors about the virulent anti-Semitism in Germany. But radio broadcasts were convincing us that Germans would not dare to attack the USSR. My father also said that there would be no war.

22nd June 1941 was Sunday and I was preparing to an exam. We had a radio at home when all of a sudden we heard Molotov’s speech [16]: the war began. I was to take an exam in chemistry on Monday. When we came to college on Monday all students were sent to dig trenches. I came home and said to mother ‘I am going to do trenches’. She cried so bitterly, because I was so sickly: I had running nose all the time and my legs swelled. ‘At least put on your galoshes!’ she fell on her knees begging me to stay, but I was a Soviet person: they told us to go and we went. In college we boarded trucks and drove in the direction of Vasilkov. We were accommodated in cowsheds. We were provided with food: there were boxes with bread and butter and sausage. We were digging trenches: it was raining, there was mud, it was cold, my legs swelled. We were there about a month. It was the end of July. Germans were advancing and we, students, had to walk back to Kiev. I came home – there was nobody in. The door was open, everything was a mess. I cried so… My neighbor Bella Pristup told me that my brother went to the front with the Polytechnic College. My parents didn’t want to leave without me, but my sister had a friend named Buma Bentsionov. He was a driver of chief of a military registry office and my sister convinced my parents: ‘Don’t worry, when Sarra returns from trenches Buma will help her’. My sister left me a letter: ‘You are no longer a small girl. Our parents have left. When you return to Kiev Buma will arrange it all’. Olia was more independent than I. Though she was younger. Buma helped our parents to leave Kiev in a special vehicle. The special school where my sister worked was modified into a hospital at the beginning of the war and my sister was employed as a storekeeper in it. While I was digging trenches Olia was sent to the front with her hospital.

I was alone in an empty apartment. There was a telephone in an office in the adjoining house. I went there to call Buma Bencionov. He came immediately and said ‘You can stay with me or I will help you to evacuate from Kiev’. ‘I shall go’. Buma helped me to join a march of military going to the front as medical nurse. I and another medical nurse were put on a wagon and the rest of them walked from the military office. We walked as far as a bridge in Darnitsa [opposite side of Dnieper River], when Germans began to bomb the bridge. All military scattered around. This other girl and I decided to cross the bridge. We walked and walked when I saw another march of military and decided to join them. There was a call to defend our Motherland. It meant to me that we had to go to the front. My sister served in a hospital and I intended to go to the front, too. I joined a military march. We walked at night and slept during the day. I remember that I walked asleep. We reached a village once and were waiting there for an assignment to the front. I met few guys from my college. I said I was a medical nurse hoping to go to the front with them. I received a uniform and a medical kit. There was a doctor who taught me to apply bandages. Young men were not used to wearing boots and had their feet rubbed sore. They used to say waiting for their assignment to the front ‘Sarra, don’t worry, we are not scared, we are communications operators’. None of them returned from the front. Once we were sitting and talking when I saw deputy director of our college walking by. He noticed me ‘What are you doing here?’ I replied ‘Komsomol has sent me’ to prevent him from asking any further questions. My companions joined me and told him that I was alone and wanted to go to the front. He looked at me ‘Just stand up, change into your civilian clothes and come with me!’ I changed and went with him. He gave me 500 rubles ‘Here, take this! I will put you on a train and you will go find your parents. The front is no place for you!’ He treated me in such father’s manner, and I had suffered so much that this time I burst into tears. He said ‘Sarra, don’t cry! I and other men like me go to the front for you, girls, to stop crying’. He put me on a train. This train took me to Poltava, [about 300 km east of Kiev]. It was destiny. God was always with me. I came to Poltava and kept asking people ‘Do you know where hospital 14-04 is?’ I was looking for my sister. Somebody called a militiaman and said pointing at me ‘A spy’. I was 20, but due to malnutrition I looked 15. They interrogated me in a militia office, but then their chief saw who I was and said ‘Go look for your sister’. I walked out, bought a bagel and kept walking chewing the bagel when I saw a guy I knew. His name was Yasha. He dated a neighbor girl who was my sister’s friend. He was young, but he had very poor sight. I didn’t look myself from hunger. He looked at me, but he didn’t recognize me without his glasses. ‘Syulia, what are you doing here? Your sister is in hospital in Kremenchug’. I went to the railway station immediately and took a train to Kremenchug. This God, God was helping me all the time. On this train I met a women who was going to the hospital in Kremenchug to see her wounded husband. Our train was bombed and we had to wait until they fixed the track after it was ruined with bombs. At last we arrived in Kremenchug [250 km from Kiev]. All of a sudden it began to pour. There were tables with parasols at the railway station. This woman and I stood by a table and waited until morning there. In the morning I went looking for the hospital and a guy told me the way. When I came to the hospital I asked someone to call my sister. She was also looking for me all this time and told everybody that her beauty of a sister had perished. You can imagine how we met! Manager of this hospital doctor Shechtel employed me as a hospital attendant.

German troops were on one side of the Dnieper and we were on another. We were at the front – we were a front team. We picked the wounded from battlefields and provided first aid to them. 2 or 3 months later we were ordered to move to the rear and wait for another assignment to the front.

We didn’t know that our parents were with my father’s relative in Dedkovo village near Voronezh at this time. Our parents missed us a lot: Boris was at the front, Olia was at a hospital at the front and they had no information about my whereabouts. My father was very energetic: he bought postcards and was mailing them all over the Soviet Union. When we were still in Kremenchug doctor Shechtel received one card. He gave it to us and we sent a telegram to our parents informing them that we were moving to Kursk region to wait there for a new assignment to the front. We arrived at Solntsevo village, Kursk region [Russia, 100 km from Kiev] and my mother and father also came to the commandant of the village knowing of our whereabouts. They bumped into manager of our hospital Shechtel. He said ‘Your daughters work with me!’ and my father came to Solntsevo with him. It was a moving meeting. My father asked Shechtel ‘What do I do now?’ and the doctor said ‘Take one daughter with you and let another stay in the hospital. It is a war and who knows who will perish at the front and who – in evacuation?’ but my father said ‘No, they both will go come with me’.

We went to Voronezh [over 1200 km from Kiev], and from there we moved to Central Asia. We went on a freight train. Our trip lasted for over a month until we arrived in Namangan [Uzbekistan, 3300 km from Kiev]. We rented a pise-walled hut on the outskirts of the town from an Uzbek man. Te owner of the hut had a vegetable garden and he allowed us to pick tomatoes from there. We were happy. Some time later my father went to work as chief of the town utilities and received a one-bedroom apartment near the railway station. My father, my mother, my sister and I lived in this apartment. My sister and I were looking for a job to receive bread coupons. I went to work at the bureau of current changes in a college. I had finished my first year of studies and knew about drawings. I inspected yards for new facilities and if I found any I marked them on a drawing and made a general layout of the section. Then I was fired due to reduction of staff and went to work in an evacuation hospital in Namangan. I was chief of logistics. Olia worked at the Water Engineering College as a lab assistant.

The local population was friendly and we didn’t face any anti-Semitism. We got a plot of land from work and this supported us. Olia seeded her plot of land with wheat and we planted pees. There were aryks [irrigation canals] and we watered our gardens. We received bread per or bread coupons. My father often lost his coupons and we ate pees and vegetables from our vegetable garden. My sister gathered one sack of wheat from her plot of land. She sold it and went to study in Moscow. In 1943 Olia entered Bauman Moscow Technical University.

In 1944 I received an invitation letter to continue studies in my college in Kiev. I arrived in Kiev in autumn 1944. There was a hospital in our house and our apartment served as a hostel of this hospital. I didn’t have a place to live and our neighbor Bella Pristup who had returned from evacuation offered me a lodging. She and I celebrated the victory on 9th May 1945 together. What happiness it was!

I was a second-year student in college. Many boys from my group didn’t return from the front. There were no relatives or friends in Kiev. I wrote my parents that our apartment housed a hospital. They arrived in 1945 after the victory. My father went to chief of this hospital and showed him the documents that his son was at the front and that we were the family of a military. They moved out of our apartment and we had it back.

My grandfather Moisha-Alter and his wife stayed in Kiev when German troops came. Our neighbors told us that Germans took them to Babi Yar [17] in September 1941.

In 1948 my sister graduated from her college in Moscow and returned to Kiev. She got a job assignment to work at the metallurgical plant ‘Leninskaya kuznia’ as an engineer. She met a foreman at the plant. He was a Jew. His name was Mikhail Shafranovich. They got married. They have two children: daughter Lara and son Vladimir. Olia’s daughter and son have a higher education. They are engineers.

My brother Boris returned from the front. He entered Agricultural College in Moscow. He married a Jewish woman in Moscow. Her last name was Yakobson, but I don’t remember her first name. After finishing his college Boris got a job assignment to an agricultural equipment plant in Riga. He was an engineer. Sometime later he moved to Daugavpils with his wife. [Latvia] Boris was promoted. He became chief engineer at the agricultural equipment plant. They live there. They don’t have children, regretfully. We correspond. When we were younger we visited each other, but we are growing no younger.

We were very happy when Israel was established in 1948, but we didn’t consider moving there. We believe that the Soviet Union is our Motherland and we shall stay here.

In 1949 I finished the Communications College and I felt a change in attitude toward Jews. My co-students stayed to work in Kiev while I received a job assignment [18] to Southern Sakhalin in 6000 km from home. [The Soviet Union acquired the Kuril Islands and southern Sakhalin at the very end of World War II.] There were only few Jews in my group, but they managed to stay in Kiev: they involved their acquaintances to pull strings for them. I decided to fight and managed to receive a job assignment to the east of Ukraine, 400 km from Kiev, in the brick factory of Kharkov. I worked as construction materials production engineer. I rented a storeroom. I don’t remember the owner’s name, but her mother’s name was Evgenia Busykina. Her husband was a priest. In 1937 his church was closed and he was expelled to Siberia. Poor Evgenia dropped a sewing machine she was carrying when hearing about his arrest, fell and broke her hip. She was still bedridden while I was living with them (1949 – 50).

When I came to work at the plant it’s construction had just been finished. There were construction deficiencies, but we were required to do the plan. I was a young specialist: I could do drawing or other technical work, but I had no experience in managing workers. They appointed me chief of the drying shop, the forming shop delivered bricks for drying in our shop. We dried it in a chamber and then placed it in the oven to burn. My workers specified bigger quantities of brick supplies in documents to sell the extras. I didn’t know that and it couldn’t even occur to me that this was possible. My situation was hard there; I had a poor place to live and at work we didn’t complete planned quantities. I fought for completion of plans for 7 months when new director came to the factory. His last name was Volk. He accused me of brick theft. Instead of helping me to clear it up he attacked me. I believe it happened because I was a Jew. I didn’t know what to do and wrote my parents in Kiev. My father went to the Ministry of Construction materials where he told them what happened and I got a transfer to the cement plant in Podol in Kiev.

Shortly after I returned to Kiev I met my future husband Chaim Shyfris, a Jew, at a party. It happened in 1950. A year later we got married. We lived in our apartment: my parents, I and Chaim. Olia was married and had moved to her husband, Michael. We didn’t have a Jewish wedding. Chaim was a Komsomol member and my father was a Communist and observation of any Jewish traditions was out of the question. We didn’t even celebrate Jewish holidays.

Chaim was born in Kiev in 1925. His father Leib Shyfris came from Belopolie like my parents. He worked as a cabinetmaker. My husband’s mother Bashyva Tachanskaya came from Belopolie. Her father Yakov Tachanski made bricks from clay and sold them. Shortly after the wedding Leib and Bashyva moved to Kiev. In 1922 their son Izia was born and 3 years later Chaim was born. My husband’s grandfather Yankel Shyfris and grandmother Rieva Shyfris also lived in Kiev before the war. They had no education and were very religious. I don’t know where they came from. They had passed away before we met. In 1941 they perished in Babi Yar. There were their prewar photographs that Chaim’s parents took with them in evacuation.

Before the war Chaim studied in a Jewish school. He liked skiing and skating. The war began shortly after he turned 15. His older brother Izia was working at the biggest Kiev military plant ‘Arsenal’. He was a turner. The plant evacuated to the rear and Izia managed to take his parents and Chaim to Votkinsk [Udmutria, in Russia, 3500 km from Kiev]. Chaim became a turner apprentice at the plant and became a turner after his training was over. He worked as a turner all through the war period staying at work round the clock at times. He had a folding bed in his shop where he took a nap and then got back to work. For his self-sacrifice Chaim Shyfris was awarded a medal ‘For heroic work during the Great patriotic war’. He completed 300-400% of his standard scope and once he even did 1090%. All members of his crew received awards. All of them received orders, but he was ill at the time and they decided to award him a medal. Chaim also took part in a dancing and singing group. They toured to villages. He said that once he went out of the warm house when it was freezing and fell ill with lug fever. He survived thanks to people's care. Director of his plant Chebotaryov called an honored therapist from Izhevsk. She took a plane to get there, prescribed injections and then visited him several times to check his condition. His colleagues attended to him: young girls cleaned and washed him, washed his clothes and floors in his room. Older women prayed standing on their knees asking God to give the remaining years of their lives to this young man. This is an example of people’s attitudes during the war.

At the end of the war Izia became a cadet of Higher Military Infantry School in Mozhga town in Udmutria.[Russia]. In 1944 Chaim and his parents returned to Kiev. He went to work as equipment repairman at a pharmacy. He did well and his colleagues treated him well. When in 1948 struggle against cosmopolitism [19] began he was fired. It was very difficult for a Jew to find a job. At one time he worked at a plant in Donbass [Donetsk Basin] in the east of Ukraine, but then he returned to Kiev. In the long run he became an apprentice of an assembly worked at the ‘Arsenal’ plant. After his training was over he became an assembly worker and then he worked as an assembly turner. After the war Izia married a Jewish girl. They had a son. I don’t remember his wife or son’s names. I remember that after the war Izia worked in commerce and then in 1970s he moved to the USA with his family and we had no contacts with them.

On 2 January 1952 our son Mikhail was born. We lived with my parents. My father went to work and my mother was a housewife and looked after her grandson. Shortly after our son was born Chaim’s father Leib Shyfris died at the age of 63 and his wife Bashyva lived 22 years longer. She died at the age of 84. They were buried in the Jewish section of a town cemetery in Kiev.

I remember the period of ‘doctors’ plot’ [20] when Mikhail was small. I heard how they accused saboteur doctors on the radio when I walked the streets. I knew many doctors in Kiev. Fortunately, none of them suffered during this period. On 5 March 1953 Stalin died. I didn’t associate the events of 1937 and the ‘doctors’ plot’ with Stalin’s name. His death was a big shock for me: we loved Stalin and believed him. We got to know the truth about the ‘doctors’ plot’ only after the 20th Congress of the Party in 1956 [21].

The cement plat where I was working was closed. I lost my job and my father’s acquaintance helped me to get a job of a lab assistant in the factory of musical instruments. I had a small salary, but I liked my job. There was a clasp in tape recorders. It had to be solid enough and my task was to inspect its solidity. I began to modify the process. I was a beauty and my chief fell in love with me. He arranged for my transfer to the quality assurance department. I was responsible for determining thickness of units and accuracy of turner work. But I was a production engineer with higher education and had to do such unqualified work! I felt hurt and I quit.

There was a Stroyindustria Design Institute in Kreschatik [main street in Kiev] and my father’s acquaintance helped me to get a job there. I worked as a production engineer for designing of brick factories in Kiev region. I often went on business trips and I got familiar with the process in no time and soon I was doing work on the level of chief engineer.

Since I went to work I had to send Mikhail to a kindergarten that wasn’t easy at the time. However, we managed, but he was small and didn’t want to go to kindergarten. My mother took him to the kindergarten and then watched him crying in the yard through a slot in the fence. Mikhail was a sociable boy and he got used to the kindergarten soon. After the kindergarten he went to a Russian school. He studied very well, he had all excellent grades.

Mikhail was very sickly in the 1st grade and his doctor said he needed to spend time in a village. My husband’s cousin brother lived in the little town of Pyrnovo in 20 km from Kiev, on the Desna River and we took Mikhail there every summer 8 years in a row. I took vacation in June and then my husband took a vacation and we stayed with Mikhail there. Mikhail was cheerful and sociable and his classmates liked him. He never had to do his homework since he remembered subjects listening to his teachers in class. He used to say: ‘It’s so hard for me! I have to get only excellent grades. With everybody else it’s easier while I must have excellent grades’. He decided it for himself. I never spoke to him about it.

Once I returned from another business trip and got to know that my management had increased my salary and promoted me. The next day I was fired. Besides me, Luba Bencionova was fired. Her father-in-law Bencionov was chief modeler in Kiev. Chief engineer of the institute Sokolovski asked Bencionov to make a nice coat for his wife. That modeler was probably too busy and didn’t make a coat. They fired us both: Luba due to her father-in-law and me because I was a Jew. Some time before this chief of our estimation department offered me a job. I went to talk to him. There were about 20 employees in the room. He took my passport and began to read aloud ‘Shylman Surah-Leya Duvidovna’. I was still Surah by my passport. I changed my name to Sarra later. ‘Shylman Surah-Leya, you know, we have no vacancies left’. I turned my back to him and walked out, I was walking along the street crying. I changed my name in 1961 for convenience and simpler pronunciation.

There was a small design institute nearby. Luba Bencionova’s husband was chief engineer in this institute. He helped Luba to get a job there and later Luba helped me to get a job of design production engineer. I got a task to design manufacture of bricks from brown coal. I made a design of a brick factory in a village. Later I made a design of a chalk factory. Then there was another project: separation of molding at the ‘Leninskaya kuznia’ plant. However, I didn’t like the atmosphere in our group. There were few of us and everybody thought he didn’t fit in there.

I met with my cousin Yefim, my mother sister Fania’s son, and told him that I was looking for a job. He spoke with chief of the design technical bureau of the construction materials trust who told him to invite me to come to see him. He employed me as a designer. They had got an order to design an automatic line at the brick factory in Podol. I took those drawings home, reviewed them and came to the office to work. I made sketches for production engineers and they were to make drawings based on my sketches. We received a bonus for this job. I was designer and received 125 rubles. I bought a wireless, it still works. I liked my job in this bureau and I worked there until I retired.

In 1959 my father died after having his 4th heart attack. We buried him in the Jewish section near his parents’ graves at the town cemetery. In 1971 my mother passed away and we buried her near my father’s grave.

In 1963 all houses in our neighborhood were removed and tenants received new apartments. We received a two-bedroom apartment in a 9-storied building on the left bank of the Dnieper in Kharkovskoye shosse. It seemed to be at the end of the world at that time. We commuted in overcrowded buses from the center of the city and it took us about two hours to get there. Now there is metro and it’s convenient. Mikhail went to another Russian school not far from the house.

My cousin Yefim’s acquaintances talked to him about moving to Israel. He received a nice apartment from his work. He was doing well at work, but he was obsessed about the idea of going to Israel. He even started to learn Ivrit. His family lived with his mother. She was against his decision. They argued a lot. Then he fell ill with cancer and died. Yefim’s older son Boris studied in college in Novocherkassk [Russia]. He couldn’t enter a college in Kiev, being a Jew. After finishing his college he got a job assignment to Tashkent [Uzbekistan]. He worked as an engineer. He got married in Tashkent and they had a child. Yefim’s younger son Marik was very fond of chess. He failed to enter a college in Kiev. He went to Lvov and entered a college there. My sister Olia’s son Vladimir Shafranovich and Marik became friends. They decided to go to Israel and that was it. They moved in 1991. When Marik left for Israel the family decided that Yefim’s wife Manya also had to move to Israel and so did Boris. Boris moved with his wife and their child, his mother-in-law and his father-in-law. Olia’s son Vladimir kept writing her ‘Olia, do come here! You’ve always helped us, you helped my sister, now I need your help, do come’. Olia and her husband moved to their son in Israel, they live in Haifa. Olia’s daughter Lara and her family moved to Germany in 1990s.

My son Mikhail finished school in 1969. He always had excellent grades in all subjects, but it came to putting marks in school certificates they put him ‘4’s in Russian and Ukrainian. [the equivalent of ‘B’] They did it to not have to give him a gold medal. Mikhail knew that it was impossible for a Jew to enter a college in Kiev. He went to the Forestry Engineering academy in Leningrad. I decided to go with him for moral support. They didn’t want to give me vacation at work, but I said firmly: ‘My son is taking exams and I must go’. I lived with him at a hostel and helped him to prepare for exams. He passed his exams with all excellent grades.

Mikhail studied successfully at the college. He met his future wife Valia Tikhonova there and they became friends. He helped Valia with preparation of her diploma and my husband and I went there to help them. Later they got married. Valia is Russian. Her mother lives somewhere in Russia. I saw that they loved one another and accepted it that Valia wasn’t a Jew. Since Mikhail finished the college with all excellent marks he had the right to choose his job assignment. He and Valia wanted to go to Siberia, but then they got an offer to go to Riga. [Latvia] We were so happy. They went to Riga and became superintendents at a furniture factory.

On 9 June 1976 their daughter Evgenia was born. She was rowing a smart and beautiful girl. They often visited us in summer and my husband and I doted on her. Shortly before Evgenia was born in 1976 I retired. 3 years later in 1979 my husband retired at the age of 54 as an invalid.

Our son Mikhail was promoted at work. He was superintendent, then assistant chief of shop, then chief of shop and then he became chief engineer at the factory. Then there was a vacancy f chief engineer at a plant and he went to work there. When he came to work in the morning he went to talk with workers. Workers of the plant elected his director of this plant. He was a terrific director!

Mikhail died before he turned 40. He went on business trip with his employees. They took a drive in a car. He didn’t have to go on this trip, but they convinced him telling him that he was the best to establish contacts. A truck rode over their car on a turn. He was sitting on the driver’s right. He was the only one who died... This happened in 1991. When my husband and I came to his funeral his workers came to me and said kissing my hand: ‘What a person you raised!’ He always helped people and was a born director.

When in 1980s perestroika began [22] Chaim and I had a small hope for positive changes in our country and even if they take place after we die our granddaughter will live to see them. Of course, there are many hardships during this turning period, but I still believe that Ukraine will become a democratic, free and prosperous country.

Mikhail died when Evgenia was 15. She finished a music school well, then she finished a secondary school and entered the Faculty of Philology at the University. Se gave music lessons in a kindergarten when she was a student, then she gave English classes. She is very good at languages. Now she has a Master’s degree. She works at the Israeli Embassy in Riga.

In 2000 I lost Chaim. We lived together for almost 50 years. I am happy to have Valia and Evgenia. They came to the funeral and spent some time with me afterward. Valia and Evgenia often call me and come to see me every year. They visited me recently. They painted windows and doors and helped me to prepare for the winter.

My husband and I lived a happy life. We had many friends and we traveled a lot. Every summer we went to the seashore. We went to concerts and theaters. Our friends and colleagues visited us on holidays and birthdays.

In 2002 Evgenia got married. Her husband Mikhail (I’ve forgotten his surname) is half-Jew. He is a lawyer and often goes on trips abroad. He proposed to Evgenia to have a wedding on the Canary Islands and they spent their honeymoon there. I am so happy for my granddaughter and I hope to cuddle my great grandchildren.

When my husband was alive he and I often went to celebrate Jewish holidays in the Hesed. We attended the synagogue and a course on Torah studies that our rabbi’s wife conducted. We got together once a week at the synagogue. She read an article from the Torah and then we had discussions about it. We were not really religious with him: we didn’t celebrate Sabbath or follow kashrut, but we liked to be involved in observation of Jewish traditions. When I lost Chaim I had a sudden change in my heart: I began to believe in God. It’s difficult for me to go to the synagogue or Hesed alone. Hesed assists me with medication and food packages and I am grateful to them. I light candles every Saturday, celebrate Sabbath, pray, observe kashrut and fast at Yom Kippur. I do not forget to celebrate all holidays, however small celebrations they are, but it is my heart’s need.

GLOSSARY:

[1] Keep in touch with relatives abroad: The authorities could arrest an individual corresponding with his/her relatives abroad and charge him/her with espionage, send them to concentration camp or even sentence them to death.

[2] Common name: Russified or Russian first names used by Jews in everyday life and adopted in official documents. The Russification of first names was one of the manifestations of the assimilation of Russian Jews at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. In some cases only the spelling and pronunciation of Jewish names was russified (e.g. Isaac instead of Yitskhak; Boris instead of Borukh), while in other cases traditional Jewish names were replaced by similarly sounding Russian names (e.g. Eugenia instead of Ghita; Yury instead of Yuda). When state anti-Semitism intensified in the USSR at the end of the 1940s, most Jewish parents stopped giving their children traditional Jewish names to avoid discrimination.

[3] Great Terror (1934-1938): During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor. Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public ‘show trials’. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.

[4] Great Patriotic War: On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.

[5] War with Japan: In 1945 the war in Europe was over, but in the Far East Japan was still fighting against the anti-fascist coalition countries and China. The USSR declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945 and Japan signed the act of capitulation in September 1945.

[6] Russian Revolution of 1917: Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during WWI, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.

[7] Podol: The lower section of Kiev. It has always been viewed as the Jewish region of Kiev. In tsarist Russia Jews were only allowed to live in Podol, which was the poorest part of the city. Before World War II 90% of the Jews of Kiev lived there.

[8] Struggle against religion: The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.

[9] October Revolution Day: October 25 (according to the old calendar), 1917 went down in history as victory day for the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. This day is the most significant date in the history of the USSR. Today the anniversary is celebrated as ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’ on November 7.

[10] Kvitko, Lev (1890-1952): Jewish writer, arrested and shot dead together with several other Yiddish writers, rehabilitated posthumously.

[11] Shevchenko T. G. (1814-1861): Ukrainian national poet and painter. His poems are an expression of love of the Ukraine, and sympathy with its people and their hard life. In his poetry Shevchenko stood up against the social and national oppression of his country. His painting initiated realism in Ukrainian art.

[12] Sholem Aleichem (pen name of Shalom Rabinovich (1859-1916): Yiddish author and humorist, a prolific writer of novels, stories, feuilletons, critical reviews, and poem in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian. He also contributed regularly to Yiddish dailies and weeklies. In his writings he described the life of Jews in Russia, creating a gallery of bright characters. His creative work is an alloy of humor and lyricism, accurate psychological and details of everyday life. He founded a literary Yiddish annual called Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek (The Popular Jewish Library), with which he wanted to raise the despised Yiddish literature from its mean status and at the same time to fight authors of trash literature, who dragged Yiddish literature to the lowest popular level. The first volume was a turning point in the history of modern Yiddish literature. Sholem Aleichem died in New York in 1916. His popularity increased beyond the Yiddish-speaking public after his death. Some of his writings have been translated into most European languages and his plays and dramatic versions of his stories have been performed in many countries. The dramatic version of Tevye the Dairyman became an international hit as a musical (Fiddler on the Roof) in the 1960s.

[13] Gaidar, Arkadiy, real name Golikov (1904-1941): Russian writer who wrote about the revolutionary struggle and the construction of a new life.

[14] Famine in Ukraine: In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.

[15] Komsomol: Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.

[16] Molotov, V. P. (1890-1986): Statesman and member of the Communist Party leadership. From 1939, Minister of Foreign Affairs. On June 22, 1941 he announced the German attack on the USSR on the radio. He and Eden also worked out the percentages agreement after the war, about Soviet and western spheres of influence in the new Europe.

[17] Babi Yar: Babi Yar is the site of the first mass shooting of Jews that was carried out openly by fascists. On 29th and 30th September 1941 33,771 Jews were shot there by a special SS unit and Ukrainian militia men. During the Nazi occupation of Kiev between 1941 and 1943 over a 100,000 people were killed in Babi Yar, most of whom were Jewish. The Germans tried in vain to efface the traces of the mass grave in August 1943 and the Soviet public learnt about mass murder after World War II.

[18] Mandatory job assignment in the USSR: Graduates of higher educational institutions had to complete a mandatory 3-year job assignment issued by the institution from which they graduated. After finishing this assignment young people were allowed to get employment at their discretion in any town or organization.

[19] Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’: The campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’, i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. ‘Cosmopolitans’ writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American ‘imperialism’. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors’ Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin’s death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’.

[20] Doctors’ Plot: The Doctors’ Plot was an alleged conspiracy of a group of Moscow doctors to murder leading government and party officials. In January 1953, the Soviet press reported that nine doctors, six of whom were Jewish, had been arrested and confessed their guilt. As Stalin died in March 1953, the trial never took place. The official paper of the party, the Pravda, later announced that the charges against the doctors were false and their confessions obtained by torture. This case was one of the worst anti-Semitic incidents during Stalin’s reign. In his secret speech at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 Khrushchev stated that Stalin wanted to use the Plot to purge the top Soviet leadership.

[21] Twentieth Party Congress: At the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin’s leadership.

[22] Perestroika: Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s. Perestroika [restructuring] was the term attached to the attempts (1985–91) by Mikhail Gorbachev to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratise the Communist party organization. By 1991, perestroika was on the wane, and after the failed August Coup of 1991 was eclipsed by the dramatic changes in the constitution of the union.