Roza Benveniste

Athens

Greece

Interviewer: Alexis Katsaros

Date of the interview: May 2007

Roza Benveniste was born in Thessaloniki in 1919. She lives in an apartment in the center of Athens. She is a woman that is involved in many activities such as working as a volunteer at the Jewish Museum of Athens three times a week. In addition, she is a woman of many talents since she speaks five languages fluently and is a talented painter. Her artwork decorates most of the walls of her warm home.

Family background

About my great-grandparents I know very little. My paternal grandfather was still alive when I was born. He was a money-exchanger. He originated from Larissa where he lived for most of his life. My grandmother was a quiet old lady with whom we didn’t have much contact. My grandparents spoke to each other in Greek and in Judeo-Spanish 1 but with a Greek accent.

My family was quite cosmopolitan and didn’t wear traditional clothes, with the exception of one of Mother’s aunts. She came to visit every now and then and she used to bring us the traditional tajicos 2 made from dough.

My father’s parents had settled in an apartment in Thessaloniki. I remember we used to go on Saturday night to listen to my grandfather say the prayers. He didn’t leave the house often, so I don’t think that he attended the synagogue. I don’t know anything about their life in Larissa.

I didn’t meet my maternal grandfather, so I don’t know much about him. I met my maternal grandmother, Belissia, who was very nice and used to tell us stories all the time. I am afraid that she died because of me. I had a cold one day and my mother couldn’t stay with me because she had to go to a funeral. My grandmother looked after me instead and she caught my cold. A little while later she died. She didn’t have a house; she used move around between the houses of friends and family. Everyone loved her very much and when she died my father mourned greatly. They had a very good relationship. I remember Father used to joke with her all the time.

My mother didn’t know Greek, we taught her the language. Her reward to us was to buy us ice-cream from the ice-cream man who used to come around the neighborhood. My mother had lived for a long time in Paris, where a cousin of hers used to live. She knew French very well and used to wear long green dresses.

My father had gone to Paris to learn couture for men’s and women’s clothes. At some point he returned to settle in Thessaloniki. My mother had come back from Paris with a European style. They met at a dance. My mother was wearing one of her long dresses. When my father saw her he was very impressed. My father was a quite short, while my mother was a stunningly beautiful woman.

My mother used to read a lot, but my father didn’t have much time for reading. She read mainly literature and newspapers, in French and Spanish; she was able to read Greek only later.

There were many Greek newspapers in Thessaloniki, and some where in Judeo-Spanish, written in Latin characters. There were newspapers in Rashi 3 and newspapers in French like Le Progrès 4, L’Indépendant 5.

My father owned a shop called ‘Com fete’ that sold clothes and trench coats. The shop used to have the nickname ‘The Trench Coat Source.’ My father was a very difficult man. He was very strict. He wanted the towels to be very well ironed, and if they weren’t he would say, ‘What is this?’ in an angry manner. When I think of what we had on the table everyday… We had to have a variety of salads as well as boiled vegetables that weren’t very common at the time, like greens.

Because my father originated from Larissa, my mother’s relatives made fun of him. They were ‘a la Franca’ [of French culture] and knew their French etc. I remember one time on his birthday, one of my mother’s sisters brought him a bouquet of fresh carrots and celeries. He was the only one in the whole family who used to eat raw vegetables just like that. All the others were very refined.

My father always kept a note pad next to his bed. This way, if he remembered something during the night he would make a note of it. These notes were the duties of each of his employees, for the next day. In the morning one of his employees would come from the house to pick up the notepad and take it to the shop.

Before the war he had established a shop that was very original, with goods from Paris. He had brought machines from Paris to waterproof the trench coats. We had a room in the house where he would store the coats while they were being made. He worked with agencies around Greece and he had a contract with army officers’ cashiers. The officers would shop at my father’s shop.

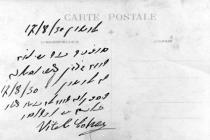

My father attended a Jewish school and he knew Hebrew and Rashi. In fact, I have a card of his written in Rashi. He would travel to France for medical treatment because he had asthma.

My father wasn’t very religious, he always worked on Saturdays. Our food was kosher anyway, because we bought the meat from the Jewish butcher. My father would go to the synagogue only on religious holidays. I don’t know anything about his personal political views.

We spoke in Judeo-Spanish and in French in the house. The Greek language entered our house much later.

We were a very large family so we didn’t have much contact with other Jewish families.

Thessaloniki was the only city where the majority of the population was Jewish. I was born two years after the Great Fire of 1917 6. Many Jewish buildings and synagogues were ruined by the Great Fire, and many were emigrating. Even though many synagogues had burned down during the fire, quite a few remained. There were many small ones, because it was forbidden for a synagogue to be any bigger than its nearest mosque. There was Beith Shaul synagogue in the posh area of Las Campagnas or Exohes, which was a very luxurious one, but there were many other smaller and simpler ones.

I remember Thessaloniki full or trams. I used to go to school by tram.

In my neighborhood we had only one rabbi. We lived in a mixed area where both Jews and Christians lived together. An Armenian doctor lived right opposite and I used to play with his son.

We were one of the first houses to get a radio. I remember it was huge and it came in many pieces. We were also first to get a bath that could be heated up with wood. The water would go through the stove and hot water would run in the bath. We used to bathe in the bath, not simply shower.

The house was heated by a cast iron stove. It was painted outside in a pale color with golden ornaments, and it stood in the corner of the living room. There was a space inside that could be used as an oven. I was very sensitive to the cold, so I would sit on my knees next to the stove with my book on top of it. My father however, couldn’t stand it and he would shout to open the windows and get some fresh air.

The staircase to our house led up to a large tiled entrance hall. We lived in a detached house. On one side of the entrance hall there was the door to the living room and on the other a large door to the kitchen where there was also a big window looking out on the garden. The kitchen also had fireplace where we would cook, which was common at the time. We would light the fire under the fireplace where there was also a place to boil clothes. We had a lady coming in help with the washing whom we used to call Miss de Colada.

We had a housemaid who lived in our house. Since we were Jewish, naturally we had a Jewish maid. The maids usually came from neighborhoods like ‘151’ 7.

We would wash our clothes with lye, which was the ash that we gathered from the fireplace. We would hang them to dry in the courtyard. These clothes smelled so wonderful.

There was a corridor from the kitchen leading to the toilet and the bathroom. At the end of this corridor were the dining room and living room. Our veranda was quite large and it was the place where we spent most of the summer. We didn’t sit in the living room very much. We usually sat in the dining room because the radio was there. From the living room there was one small corridor that led to my parents’ room and to the room I shared with my brother. They later split my brother and me up, and I moved to the room opposite.

There was a coal stove in the dining room which had a large stove pipe, and another one in the living room. We had a brass brazier which my father loved. We used to put small pieces of coal in the brazier and close the door at night, and in the morning, when we woke up, the room would still be warm. We didn’t have heating in the bedrooms. I remember my father, first thing in the morning he would wake up and go to break coal in small pieces. The brazier was wooden and had a brass can and I have a very faint memory of it.

We had a garden outside the house which also had a greenhouse. We didn’t grow anything inside the greenhouse; we used to put all the plants inside in the winter so they wouldn’t freeze. Later, the Germans put pigs in there. They even took the shutters when they left.

We weren’t a very religious family, and didn’t go to the synagogue very often. My mother was a ‘libre penseur’ – a free thinker. Of course we celebrated the religious holidays. I had this teacher at my uncle’s school who taught us the Haggadah, the whole story from the time of our exodus from Egypt. We never really learned it because we would just repeat everything without paying much attention to it.

The Zionist issue was quite big at the time of my birth. There where many unions like the AJJ Association Jeunes Juifs 8. They had given out these boxes and every month they would come around the houses and collect money which was sent to Palestine to buy land from the Arabs that they didn’t cultivate. The earth had become so sterile. After some time, when the Arabs realized what was going on, they raised the prices much higher. With these savings is how Israel was created. I would put all the change from the shopping in the box.

Growing Up

There were even more serious and dynamic unions like the one of Theodor Herzl 9 and some others more fanatic. I only remember the two unions that I just mentioned; I was a member of Theodor Herzl’s. We didn’t really have any specific political beliefs. We would gather, chat, and dance. It was a way for us to meet and hang out together. Sometimes we would even go on daytrips. I didn’t get to go to many places, because I was quite young and I got married very young too.

There were many Jewish schools which were founded by Alliance Israelite Universelle 10. They had founded schools everywhere. There were also many schools from different nations in Thessaloniki, like the German school, the American and the Italian. When I was very young, I went to a kindergarten that a cousin of my uncle owned. This uncle had a school for Jews only. The others had schools for their own people. There were so many Jews in the city anyway.

My uncle’s school was called the Ecole Franco-Allemande, because he taught French and my other uncle taught German. My uncles’ school offered a high level of education. With this knowledge I took exams and got my degree from the Lycée Francais.

At my uncles’ school, we were taught Hebrew. We didn’t really learn the language, but we learned some prayers that I can still remember. Then they thought that this wasn’t a very efficient way of teaching, so they got us a teacher from Israel who taught us literature and another one who taught us Rashi – that is the Judeo-Spanish written from left to right. I learned English at Anatolia College 11.

I didn’t learn Greek properly, because at my uncles’ school we didn’t really learn Greek, and after, at the Anatolia American College, we did everything in English, which was good because we practiced the language more this way.

The American school was mixed. It was for girls only but it had girls from a variety of different nationalities. There were many foreign students in the school who lived in the dormitories inside the school. One girl was from Albania, another one from Turkey whose name was Talat. The headmistress was called Miss Morel. We had two Armenian girls, whose fees were lower because of how they had been treated by the Turks. The girls who lived in the dormitories helped out in serving the food and many other tasks.

I didn’t live in the dormitories. I was with four Greek Christian girls and the Abbot sisters. I was also with two Jewish girls. I don’t know what happened to the one of them, but the other one married Molho, who had the bookshop in Thessaloniki. One of the Christian girls was Eugene. She was a very close friend of mine who had an old mother and no father. I heard that during the occupation she was taken to Germany. Why she was taken to Germany I still wonder.

Most of my schoolmates had gone to another school first like the Lycée Francais. My uncle’s school shut and I went straight there too; I was the youngest one in the school. We had a great teacher at school who taught Ancient Greek in translation and I was a very good student of his. He had this Olympian look to him, with blue eyes and a big forehead. We were all crazy about him. He had written schoolbooks and was very educated.

In our free time from school, we would meet for tea. We would invite boys for tea and they would invite us too. In our last year the girls who were one year younger than us invited us for tea to bid us farewell. They even made up these lyrics for us. The one about me said: ‘Here comes Blondie Roza with her serious ways but she is also a coquette; now she is full of sorrow because she will miss the president’s position.’ I was the president of the school when I graduated.

It was a tradition for the graduates’ class to go on a trip to Athens in order to visit the ancient sites. The Abbot Sisters had contacts with embassies and ambassadors and they had this idea that we could go to Italy. ‘How are we going to go to Italy,’ I asked them, and they replied that we would write a letter and send it to the embassy. So we did, and waited for their answer. As all this happened in 1938, the answer took a long time to come, so we had already gone to Athens. But when we came back, arriving at Thessaloniki’s harbor, our headmistress was waiting there for us and said, You know, Roza, there is a letter for you from the Italian Embassy.’

The letter we had written said how much we admired Italian art, which we had been taught about at school, and that we would like to see the originals. So they replied, accepting our request, and so we could go. They explained where we would stay and that we would have 75 percent off on all train tickets around the country. Basically, we would pay for the trip, but for wherever we would go the youth union would receive us.

Some of the girls didn’t have enough money for this second journey. We all needed to exchange money and with Metaxas 12 at the time, it was very difficult because he wouldn’t allow any exchanges. We split in two groups: one to find who would exchange money and the other to convince our headmistress to find an escort to take us. Because, how else would girls travel on their own especially all the way to Italy? It was unthinkable.

So I would go to the headmistress and each time I thought that I had managed to convince her, she would come up with some excuse, not to find us an escort. The other girls went to the banks but they didn’t manage to exchange any money. At some point one of the banks’ employees said to the girls: ‘But girls, aren’t you from the American School, don’t you have dollars on the side?’ So we managed to exchange some money. In the end the Abbot Sisters found an older girl whom they persuaded to escort us.

We went on the ferry boat from Thessaloniki’s harbor with the Tsiteris company. We had arranged with the company to take care of our mail to our families too. So we got to Brindisi or Bari, I don’t remember which. But no one was waiting for us there, not even a reception group, nothing. Our escort took charge and she found a solution. We went to Milan, Lago di Como and Venice. The day that we arrived, Mussolini 13 was also in town and we would joke and say that they were expecting us.

It was common in the films in the cinema to watch Venice with the gondolas and the couples in love kissing, on them. As I was a young girl at the time, this is the image that I had. I felt quite the opposite when I was there because they had nothing to do with the image that they projected in the films. At some point I stopped and said, ‘This is the gondola that I want.’ So the girls turn around to me and say, ‘But this one looks like a hearse, its all with black and white.’ I hadn’t noticed that it was actually black and white as it was richly decorated and that’s what had dragged my attention most.

In Rome, they showed us around and took a picture of us for the local newspaper. Florence was the city that made the greatest impression on me with its aristocracy.

My mother would shut me in the house around Easter time. There was a greater anti-Semitic wave during those days. This story was that I, being Jewish, killed poor Jesus so they had to kill me too. After Easter they would forget it again and everything would go back to normal. We would all hang out together.

The first time that I actually felt so bad that I was Jewish was on this trip to Italy. We had gone to Rome and many students had come to show us around the city and one of them who was closer to me and was showing the city to me says to me at some point, ‘See this shop? It was owned by a Jew and now we took it over.’ So I instantly asked him why, and he replied, ‘Because now they are ours.’ So I turn back to him and with no shame what so ever I reply, ‘I am Jewish.’ ‘Oh,’ he says, ‘we want Jewish women; we want them in one and only one way though…’

That was the first bite that I ever felt, the first sense of what was about to follow. From that moment, I started being homesick. I described the incident to the girl who was escorting us and she said that it was forbidden from now on, to tell anyone else that I was Jewish.

I didn’t have a lot of free time, because I was having private piano lessons, phonetics, music, painting, and these paintings over here [the interviewee is pointing at the paintings in her living room, which she drew] I did.

I had an art teacher, Miss Zukofki. I thank God for the good teachers he has given me. She was from Belarus, and her husband was an army general. The tsar baptized him. While she was in Thessaloniki she taught at the Lycée Francais. She would come to my fathers’ shop to buy clothes for her husband. At school I really liked to take a piece of paper and make portraits of my schoolmates. My father took my drawings and showed them to her, and she told him that I had a talent, so she started coming home to teach me. She taught me drawing and pyrography [art of decorating wood or other materials with burn marks by applying a heated object.]

I made a small shovel with its brush like the ones we have for the table, on top of which I had put some leaves. I also made a few things from leather. I liked them very much and so did the Germans because they took everything that we had left in the house. I made this board, which was a basket with strawberries, and it was a very successful piece.

There was a shop in the market, which belonged to Mr. Bourzopoulos, who everyone liked very much, and all his fabrics were imported from other countries. We were well known. Madam Cohen with Miss Cohen, Mrs. Vital Cohen. I didn’t go out to the market because the boy would come and pick up from the house to take to the seamstress anything we needed. At the time they wouldn’t even let me carry a single box.

My mother would give the shopping list to my father every Thursday. If she needed anything extra in the week she would buy it from the salesmen who would come around the neighborhood with their carriages of fruit and vegetables. Some of them we knew for years. At the time, the okras we would buy from Gypsy [Roma] ladies coming round, and they would come to the door and show us big bags full of okras. They where quite small in size, and they would sell them by the piece. They were so delicious. One of the grocers would come by and shout out the name of my mother. This is how well we knew them.

I had an older brother, Alberto, who was born in 1916, and whom we nearly lost during the mobilization because he was acting as if he was going to save Greece on his own. All of a sudden they came and took them and put him in a hospital that had a wing where they treated malaria patients for free. It wasn’t very much like a hospital, it didn’t have any medicine and he kept saying to everyone to be patient.

When my brother got married, he didn’t want to stay here and hide, so he and his wife decided to escape to Israel through Turkey. Silly of him, he took some gold liras with him and hid them in his boots. But he didn’t wear those boots; instead he had tied them up at the sack that he was carrying. The guy they had paid to take them took the money, took them to the island of Evoia and told them to wait there. A boat was supposed to come to pick them up. They waited and waited, but the boat wasn’t coming, so they understood that he had fooled them.

They started searching for another captain to ferry them over to the other country. They found someone, who took on his boat as many people as he could. But when they sailed, he realized that the boat was overloaded so he took the luggage and threw it one by one into the sea without saying anything to anyone. This way my brother lost his boots and his money with them, and even if someone found them they wouldn’t have known that money was hidden in them.

Eventually he got to Turkey with his wife, completely penniless. Luckily, there was an organized welcome by the Jews of Israel, then Palestine. The Turkish Jews took care of them and sent them to Palestine, where Jews already had set up their unions and they where trying to build their own army and create their own state. They took my brother as a postman. He later had two girls. A whole community of Greek Jews later on settled there.

My brother Albert fell in love with a girl that wasn’t of our class, you could say, but because he had gone through so much by then, and we thought we might lose him, we didn’t make a fuss about it. In the meantime there was the war going on, so we wouldn’t pay attention to such details.

His wife was the only one that didn’t go to the concentration camps. She was saved by her family. Her younger sister had gone to the concentration camps and came back, but unfortunately, due to the beating, she was deaf when she came back. I know that she later went to Israel, but I don’t know whether she is still alive or not.

My husband Rene came from Kavala [city in North-East Greece] and he had lost his mother and sister to World War I. They didn’t have a refuge, so the whole family was together, but I don’t know where. Anyway, when they got in, my husband hid in the corner. His father went to take him from the corner to be with the rest of the family. At that moment a bomb fell and all the others turned into ashes, and only the two of them survived. His father Nisim married a relative of his mother Siniorou, with whom he had a son named Pepo, and so my husband had a new brother. My husband came to Thessaloniki with his father and brother.

My husband worked in Thessaloniki, and his father knew an uncle of mine of whom my grandmother used to say, ‘I gave birth to all my children, but this one I must have taken from Paris.’ He really was ‘sui generis.’ He was very cheerful.

He would get up in the morning and sing his songs. One day the two of them went out in Thessaloniki to play billiard. So my uncle asked him if he was planning to get married or not. He said, ‘Yes, but I have to find a good girl.’ So my uncle told him, ‘I have a niece; I will introduce her to you.’ By the way, I really disliked things like that. I had contacts with other Jews from Unions, but nothing was happening there.

I had an aunt, Mathilde, who was one of my mother Flora’s sisters. She was more modern, and sometimes we would go out together to the cinema to watch a movie. One day she comes and tells me about this good movie that was playing in the cinema, and whether I would like to go. So I say, ‘Yes, let’s go.’ It was a cinema by the seaside; it doesn’t exist anymore.

So while I am ready to go out, my mother starts off at me saying how am I going to go out with this coat? I started getting a bit worried, because she was acting strange. I had many clothes that were assorted with their hats, as it was unthinkable for a lady to go out without a hat.

My aunt came to pick me up, and supposedly because it was a nice day, we went on foot. The weather wasn’t so good, but I accepted. On the way, she started telling me about this guy, so I started introverting, and I was thinking, who knows what he is like. So we get to the cinema and they weren’t there yet, which really surprised me. They came in after the movie had started, and my aunt waited until the movie had ended and the lights were on, in order to speak to them.

After the lights were on, we decided to walk back home, even though it wasn’t a very good night. The walk from the White Tower to the house wasn’t very long, but at the time it was very dark at night in Thessaloniki because there weren’t many lights, and we could hardly see each other. Any time that there was light on the way, you could see both our heads turning just to catch a glimpse of each other.

I was quite upset with my mother, who hadn’t told me anything about it. So when I came back home, she asked me how it went. ‘Fine,’ I reply and so does my aunt. My mother wanted to learn more, so she got my aunt and started asking her. ‘It went well,’ she said again.

On his side, he was trying to make up ways so we would meet again. He started being friendly with my brother and the three of us would go out together. One day he says to my brother, ‘Hey Albert, why don’t you leave now because we have a few things to talk about,’ and this is how our relationship moved on. Later, I got ill and he sent me so many flowers and cakes and then phone calls and everything, but he wouldn’t dare to come around the house.

Once he rang his father in Kavala and said to him, ‘Bring your wife and come to Thessaloniki because I am getting engaged.’ His father thought that he was joking at first, so he told him again and said that he was not joking and told him who he was going to get engaged to, his friend’s daughter. And then he believed him. We had our engagement at his place and we kept an open house for three days.

The ring, as you can see, had a different setting, but at some point, when we were staying in Switzerland, there was a huge dog where we were staying. One day, when we came back from our walk, the dog jumped on me and ruined it. They felt very bad; it was made from onyx, so they took it to their goldsmith to have it fixed. At another point, I lost that stone too. My husband had an obsession with the pendulum with which you can find water or metals. He read a lot about these things.

We lived in a house in Kalithea [suburb in the south of Athens] where there was a small room from which you could go through some small stairs to the maid’s house. I went up there one day to get a mattress and as it seems the little teeth that were holding the stone opened wide and it broke. My husband took this thing and started looking everywhere for the missing rock. He says, ‘It is over here,’ and there it was. My mother and my brothers-in-law were making fun of him, until he found it where he said it would be.

We got married at the Matanot Laevionim 13, which was an organization that gave food to poor children and a synagogue at the same time, and they did weddings. Things started looking quite ugly. Initially, we were going to leave for abroad, but Metaxas wouldn’t allow people to exchange any money, so we went to Athens and from there to Corfu. There my father sent us to one his agents, Mr. Dede, in order to help us out. We stayed in a hotel in Kifissia when we were in Athens, one that still exists.

When we got to Corfu, the first night we stayed in a hotel and the second one we went out to find Mr. Dede to help us out. We got our coach and went there, but first my husband went to check if they were there and if they would take us in. I waited outside. My husband rang the door and a little while later he came down with a fat lady, who came straight towards me to hug me and said, ‘Roza my child, you came back?’ I thought that she was crazy. Anyway, she kept hugging me and wouldn’t let me go.

There was a tripod there, as you entered, which had a painting and it had written something underneath, which I think was ‘Et rose elle a vécu ce que vivent les roses, L'espace d'un matin.’ [Editor’s note: Famous line from the poem Consolation a Duperier by French poet, critic and translator Francois de Malherbe (1555-1628)] They had married quite old, and they had a little girl, who they named Roze, and who died very young. She thought that her girl had come back.

I couldn’t tell her anything while I was there. I had everything I asked for. She would come by the hotel every morning and ask me what I would like to do. It was a very moving situation. Her husband was called Sabbie, and they both had this rhythmic accent like the Italians do.

They had a bone fan, and accidentally I said I really liked it, so they gave it to me straight away. After that I was very cautious of what I was saying. Many times, I look at the pictures and I wonder what on earth happened to all these people.

During the War

I got married young and I wasn’t a great housekeeper, but my mother was. I came to Athens with my husband in 1939. We stayed in Kallithea, near the Sivitanidio School [Public School of Arts and Crafts]. It was convenient for my husband because it was easy for him to get the train to Piraeus where he worked. The Commerciale [tobacco company] was located in a large field where a big hospital of Piraeus is now. I was already five months pregnant.

After the ship ‘Elli’ was sunk [the sinking of the ship ‘Elli’ precipitated Greece entering WWII], they called my husband and all his class for retraining. At some point I wanted to see what my husband was doing so I went to Kavala and met with him between two alarms. After that I returned to Thessaloniki to be close to my parents.

That day we were all at home, my husband was about to leave for his retraining when the phone rings. It was the Head of General Staff who called my father to tell him that we were invaded by the Italians and to warn him to take measures. My father woke us up and told us what was happening. So we took what we could, whatever we could take from the whole place. We also made fabrics with gold liras sown into them that we put around our waist, so in case we split up, each one of us would have some money on him.

My father rang one of my mother’s sisters’ husbands, who he had a good relationship with, to warn him too, but he couldn’t understand what my father was trying to tell him on the phone, so he told him that they would speak the next day. He was a wood trader.

My father had great foresight and, othr than all of us, he also saved another fifteen relatives, by paying a man to go and pick them up by car and take them to Athens. My brother was so single minded that all the employees of my father had moved to serve in Athens, and my brother wouldn’t allow this and was doing his army service as designated. He had forbidden my father to get in the middle. When he got ill and my father found out, he got someone to go and bring him back. Before he went to the army, he was a fearless man. Because of his illness, he got so thin that he came back half his weight.

In the meantime my brother was in love with a girl in Thessaloniki who wasn’t really of our class, which wasn’t acceptable in those days. Her name was Stella, and at some point she came to Athens to get married. We couldn’t afford to have a proper wedding reception, but our parents invited everyone for dinner, and one of the ministers’ assistants was invited there too.

My mother had kept her long dresses for receptions and formal dinners so she thought, since it was her son’s wedding, it would be nice to wear one. She had this stunning brooch with rubies and diamonds that she wore it with.

Anyway, the minister assistant, when the war started, told Father to go and stay around his place. By that time our house was under requisition because of its position, next to Sivitanidio, and they had sheltered doctors there because they didn’t have enough houses to put them. Our house was built by a Greek-American lady and it was very comforting and modern. We used to ring the bell that was in the living room for the maid, and our parents would think that it was someone at the front door, and we would joke around. Together with the house, they took the furniture too.

In Thessaloniki things were even worse, so we didn’t get a house, even though the government was obliged to give us one. This way we would get straight on their lists, so we thought that wouldn’t be a very wise move. We took some furniture to our neighbors to keep it for the time that we would be gone, and, luckily, we had the opportunity to get fake identification cards so we took on the name of Vamva. I kept my name Roza, as it was used as a Greek name too, but my husband, whose name was Rahamin, and got the nickname Rene at the Lycee Francais, was now called Yannis Vamvas.

After that we went to Pagkrati where we stayed opposite a large building plot that was used for executions. They would shoot in the night and after the shooting everything was dead quiet, like you were in the dessert. Later in the morning, you would find little papers saying who they shot, for example they would say: ‘The Germans shot this one who was a communist.’ And if the Germans didn’t do it themselves, then the Gudarades did; that’s what they used to call the people working together with the Germans.

One day someone in the street recognized my father-in-law and everyone was very scared, but thankfully this person proved to be a good man. We also had to be cautious with my child because he was circumcised and everyone was telling him to be careful when he pees. Every morning the father, grandfather and brother would say farewell to the child and go to work. Their job was to go to the 1st cemetery, which was close to where we lived. The child was very friendly with a boy who lived across the road and his name was George, but the called him Bouli.

My father together with his brothers owned a whole building. The corner shop was a shoe maker who had in the basement a dried up well where they had hidden the leathers. This is where they caught the older brother, who then had a son and a daughter. One sister was saved from the concentration camps. The other sister was having a bath when the Germans came in the house, so she heard them and she jumped out the bathroom window and ran away.

She went to some neighbors with whom we had good relations. They kept her safe for a while but when they got scared they turned her in to the Germans. The car that came to take her in passed right from the center. In the car it was only her and the driver. At some point the driver stopped at a kiosk to buy some cigarettes, someone saw her and gave her a signal to get out of the car. The little one got out and left. She didn’t know where to go because we were all hidden in secret places and people didn’t know where we were. A friend of my father bumped into her on the street and asked what had happened. He took her with him and he somehow managed to get in contact with my father.

My father got in touch with a friend of his, who was lawyer, and they hid the girl. My father was paying them of course. At the time, if a Christian family hid someone in the house, then you would cover all their house expenses as a payment. Things were awfully expensive. All the money was coming from where we had hid it. My father had many acquaintances, one of who was the minister of transport, before he was in hiding.

My son was called Alberto and we would call him Taki. But we had to teach him now that he wasn’t called Alberto Benveniste but Taki Vamva.

When we lived in Kalithea, in this house that was built by this Greek-American, it had four apartments. A couple that didn’t have any children was living in one of them. We became good friends and the lady really loved our child. When it was really cold and we couldn’t warm up all the apartments, we would warm one of them and be there all together. The lady would call my son many times to come over to their apartment and he would go, but after a while he would get bored and come and cry out, ‘Mum did you call me?’

One day we were at their place and they asked him what his name was, so he replied Takis Vamvas. So they ask him, ‘Do you know an Alberto Benveniste?’ And he said that he was gone. Later in the house my son asked me, ‘If we go back to our old house, will Alberto come back?’

My father-in-law was a goldsmith and clocksmith in Kavala. He had all these tools that the little one really liked and he had asked his grandfather to give them to him. One day the little one goes to his grandfather and asks him, ‘What is God?’ So the grandfather replies, ‘God is the father of all.’ ‘Even Grandfather’s father?’ ‘Yes, even Grandfather’s,’ he replies. So the little one thinks about it for while and says, ‘When God dies, I want to be God.’

The house in Pagkrati was owned by a pistachio seller. You would enter the house and you would enter the dinning room and we had the same furniture that you see here today. We had our comforts in the other house in Kalithea, we had gas for warming the water for the bath, which was very convenient for the baby. And then we went to Pagkrati where there was only one work surface in the kitchen and a small toilet with only a curtain. We passed through some difficult times there.

Right opposite us there where living two brothers who were also Jewish. One of them was a French teacher, but he had lost all his papers, even his school certificate from the Lycee Francais. My husband really helped him because he managed somehow to get the proof that the boy had graduated from the Lycee Francais to the French Embassy, and he got a teaching license.

We used to have a speaking trumpet to make announcements. One day they came and called all the men of a certain age to present themselves at a place which they used to call ‘The Widows Café.’

There were two rooms in the house where we lived. In one of them was my mother-in-law with her son, and we had the other room.

My husband had some money on him and he didn’t know whether to take it with him or not. We were in a quite poor neighborhood. We would also see the men wearing masks who would turn people in, and no one was sure of anything, that is, who they were going to turn in next.

So all the men left, and I took my mother-in-law, who didn’t know any Greek, and put her in bed and told her not to speak at all, not even move. She couldn’t remember any names, she would ask my son to remind her of people’s names.

As I told you before, our house was right opposite the building plot which was used for executions. One day a young man was running because he was late, and they stopped him on the way. They asked him why he was late and said that he was writing on the walls so they shot him right there. You weren’t allowed of a second chance about anything.

My son was watching that from the window. That same day an army general comes in and asks us where we keep the guns. ‘We don’t keep any guns, you can look everywhere and check,’ I reply. So he looks in front of him and sees this sideboard here and looks at the glasses and the things inside, things that weren’t common for that area.

So he asks me, ‘Where do you come from?’ ‘From Kavala,’ I reply. So he asked me if I knew a man called Yannis in Kavala. So, I asked him if he knew Kavala, and he replied that he had served in the army there. So I say to him, ‘Look our father was very poor and he was selling clothes by the sea to raise us’ – and I was thinking, poor father if you hear me now, what am I saying about you.

When we came to Athens my father had taken measures. He had a shop at Nikoloudi arcade where he was hiding the goods that he brought from Thessaloniki. He also left his head accountant in Thessaloniki to wait for him to come back. Initially, Athens was taken over by the Italians so we were treated the same way as the Christians. One day the shop owner suddenly decided that he needed the shop and asked my father to leave. So my father took everything and came to Athens.

He had the shop with an associate and his name wasn’t showing at all. In Thessaloniki all the Jewish customers would come and the Christians would go to their own well known names of couture. When the shop opened in Athens, no one knew that it was a Jewish shop, and the name was Christian. They would admire the clothes, and they would say to each other, ‘Athens you see…’ So my father wouldn’t say anything until they would buy and afterwards he would tell them, ‘You had the same in Thessaloniki, but you had to come to Athens to buy it.’

Later they occupied the shop too, and my father again opened a shop together with a Christian, this time on a very popular street, the name of which I cannot remember. When things started getting out of hand, he hid the goods under a friend’s name in the State Warehouse.

Sometimes my father would take goods from the State Warehouse, and he would sell them. At some point a nasty old man understood what was happening. This resulted in the Germans finding the goods and the Christian going to prison. The goods were sold to firms that are still well known today. My father was telling me that even after the war he could see in the shop windows things that he had brought himself from France. Thankfully, my father’s friend was set free.

This minister’s assistant and his wife, had put it in their mind to take everything that we had, and then turn us in to the Germans. After that I suddenly got a heart problem. I don’t quite remember what happened but I was down in the bathroom and I couldn’t go back up. I crawled on my knees back to the room, that I remember. Thankfully we had these good friends in Kalithea ad the man took me to the doctor and he said it was my heart. Since then I have had three operations.

Around the end of the war, my parents lived in a house at Ilisia, where an Army General’s wife was living. She had a son who she couldn’t sustain with the pension she was receiving alone, so that’s where they were staying at the time of the liberation.

I had become really tiny, I had lost a lot of weight and my parents were giving me food to get stronger, and I was going out sharing it, so eventually they took me with them to get me back to normal.

I remember on liberation day, Papandreou 15 came out on Syntagma square and all the women were dressed in army clothes and the people were shouting, ‘Government by the people,’ and he came out and said, ‘We believe in a government by the people.’

Then the Dekemvriana 16 came and we suffered very much. We were living in a socialist area where they would gather men so they wouldn’t take them as soldiers in the army. We didn’t have any food, and also had with us my father- and my mother-in-law and their son.

The community at the time was donating – contributing things. One day, we got up with my uncle and went to get the things from the community, which was at Thiseio, where the synagogue is today; it was being built at the time. On the way we could see many destroyed houses, which had been bombed. While we were walking a bullet came towards us and passed just between us and the wall. We could see bodies everywhere, but I didn’t pay any attention to that.

We passed by a grocer with his donkey on the way there, and I was trying to get some fruit from him. My brother-in-law got very upset with me. When we got to the synagogue, there were some corpses there of people who got killed accidentally from bullets. We got home and gave the food to my parents-in-law and headed off to go to Kalithea, to my parents.

Some brat from the resistance stopped us on the way and made us sit on our knees, and we were begging him to let us go. We got to a certain point, but we got stuck because it was tea time, and at tea time all English soldiers would stop anything they did to have their tea on time. In the end we got there.

The owners of the house in Kalithea had a chicken called Birbilo, and the woman was so soft hearted that it wouldn’t even cross her mind that we might eat the chicken. But you can imagine, how, at a time when there was no food all, the thought of having chicken seemed like… Her husband went and strangled it, and later we ate the chicken. The woman didn’t even take one bite.

Many times I sit and think: What if we had done things differently? … Like one time when the general came into the house and, after he asked if I knew Yannis from Kavala, went straight up to my room. He found money on the furniture and I winked at him to take it. So he replied to me, ‘Madam we are not thieves’, and I said, ‘Who said such a thing?’. He took the money and left, without bothering with the other rooms of the house at all. I was so upset that I sat at the sewing machine to get my tension out. A little boy comes in then and tells me, ‘Mr. Yannis went to work,’ meaning that there was a big piece of land and they got some people out. It later turned out that they were Jewish too. So we thought that next time it would be our turn.

There was a woman doctor living opposite our house who was working at I.K.A [Social Security Service] at Piraeus and she was from Crete. She was sometimes coming around ours to hide. Only if she knew… She was a pediatrician too, and when our little one was ill we wanted to take him to her to examine him, but we were afraid that she would see that he was circumcised. In the end we took him, and she didn’t understand a thing. I gave her English classes in return. She would come and check up on him, and we would give her something to eat.

When the war ended, I made a nice cake and called a little boy to take it to the doctor’s house. I could see the little boy from the window taking the cake and giving it to her. I had to go around a bit later for the English lesson. When I went she told me, ‘Someone sent me this cake; it is tasty.’

I had told the boy to tell her that it was from Mr. & Mrs. Benveniste, so I asked her who had sent her the cake. She replied that she didn’t know, some foreigners; she obviously hadn’t caught the name. I asked her if she liked it, and she replied, ‘Very much.’ She had already eaten half of it.

So I got up and presented myself and said to her, ‘My name is Roza Benveniste.’ She was at a loss of words, she didn’t know what to say. She was a very nice and very active woman, I later lost track of her, I don’t know why.

I went back to Thessaloniki in 1948, when Sarah, our daughter, was one year old and my father died.

My father went back to Thessaloniki to see what had happened. He also went to Israel to see his son, my brother. As I said earlier, my father was a very insightful man. He had a nephew who was the son of his sister. She lived in Palestine for many years, and her son was an architect. My father had then bought a plot of land in Rehavia, the most aristocratic area of Jerusalem. With the war ending, we had to pay all the taxes for the years that had passed so we had quite a debt. My brother wanted to sell it too, so we did, which wasn’t very wise, as it had a great value. My brother wanted to extend his business and to buy a house, so Father went there and arranged everything for him.

Later he came back to Thessaloniki, where he died, and I went there with one-year-old Sarah in 1948. We traveled on the plane and as my mother-in-law had told Sarah to wave at her from the sky when the plane took off, my little one was waving from the window.

The house was taken by the Germans. In the greenhouse they had put pigs. Some Bulgarians had taken over the shop, and all the engines and everything in there was wrecked. The shop was at 15 Venizelou Street [central street in Thessaloniki]. Some refugees were in the house, and there was one family living in each room. The shop is where Kodak Counio is today.

Unfortunately my husband, who was very sweet and nice, didn’t have a clue about trade, he was an accountant. Anyway, we spent my entire dowry during the war to survive, we sold the house in Thessaloniki and made it into an apartment building, and we sold the shop to Counio. He had a small shop between ours and my uncle’s.

It’s like I wasn’t Jewish, I didn’t know anything about trade, nor does my daughter, Sarah. When I finished school and before I got married, my father took me to the shop to work for him. He had old goods and newer ones. My father had a reward system for all the salesmen if they sold the older things, so they would get a profit too.

So I go to the shop to work and a girl comes to get fabric, you could tell that she didn’t have much money. So she called me and asked me if this fabric suited her, I replied no, this one suits you better. The employee next to me said that if the shop had me instead of my father running it, it would shut. ‘Why?’ I wondered. That suited her and you could tell that she didn’t have much money; I couldn’t lie. So you can gather that the trade wasn’t really my thing.

Later I got engaged and married. When I was pregnant anything I would eat, I would throw up later. I got to the point that I was in bed and couldn’t get up. We had these clay jars in the kitchen and my mother would make various pickles from cabbage and peppers and other things. One day she comes to my bed and says, ‘Roza taste one to see if they are done.’ I didn’t usually eat spicy peppers, because I didn’t like them. I ate one or two, and I started crying because they were so spicy. But somehow I didn’t throw up.

That became an issue. What had I eaten and did not throw up? So my mother replied, ‘I know she ate some peppers.’ From there on, I stopped throwing up and before that my husband used to go to get me the most expensive fish roe. I would get up in the morning and instead of milk, eat spicy peppers, and let the tears flow.

I had come down to Athens with my husband before the war because they had re-assigned him from work for Commerciale where he was working. After ‘Elli’ sunk and he was reassigned, my husband went back to Kavala and I took the child and went to Thessaloniki to be closer to my parents.

I remember that we celebrated the religious holidays, not so much the Christian ones, but sometimes we would visit some Christian friends. We used to celebrate Saint Johns – Ai Yanniou when we were hiding. Because my husband had the name of Yannis Vamvas and because we were in a loud neighborhood, we would celebrate it too, just like everybody else. And I remember him saying, ‘Come it is my name day too, come to celebrate,’ and we would wish that it would be the only time that we had to do this.

We didn’t go on vacation much then. My mother had arthritis so she would go somewhere outside Thessaloniki, to some hot springs. One time that I was with mother there, they had this dancing contest for couples, and I was awarded the title of ‘Miss.’ I was the ‘Miss of the dance floor.’

When the Zionistic movement had started in Thessaloniki there were unions like the AJJ that where organizing balls and excursions. These were just day-trips, of course, because our parents wouldn’t let us sleep outside the house. We also visited Prespes Lakes. My aunts used to go on vacation and sometimes they would invite me over; they had younger children so I would go to keep them company.

My maternal cousins were older than me so I didn’t go out with them. I had many friends from the American School, but they were mainly Christians. I didn’t even go out with Rene, who we were also related to, because she had an uncle who was married to one of my aunts. Her name was Rene Saltiel and she later became Molho. We didn’t hang out together much because they were three sisters and they had a circle of friends from the Lycee, and I didn’t know anyone from the Lycee.

I had another schoolmate I hung out with, Antigoni was her name, and she had six sisters. Her father worked at the tolls. Because he had a job at the municipality, one of the daughters went to work there too. She had already finished school when she came to the American College, as most of the girls had. Her stop was Papafi, but we would get off the bus at my stop, which is where the King was killed, at Agia Triada Church. That’s how we became closer. When her father died, she was very sad, so I kept her company and she used to come around the house, or we would go to the cinema with my brother. Antigoni knew how to read coffee cups and cards; she was familiar with both fortune telling rituals.

When I got married and my husband knew that he was re-assigned to work in Athens, she was around the house, but I hadn’t told her anything. So she reads the cards for me and says, ‘Roza what’s going on, I see Rene going on a journey.’ ‘No,’ I reply, so she reads the cards again and says, ‘What you are talking about, you are already there.’ I believe in card reading because I have seen it come true many times. All this was happening just before my son was born. So when she said that, I got upset, started crying and told her to leave. I had some other incidents with cards in my life.

After the War

After the war I went to Thessaloniki where many families were living in our house. In one of the rooms lived a girl from Crete; Miss Carina, whose job was to maintain the toilets of the National Theater of Thessaloniki. She was a coffee reader.

At the time one of my mother’s sisters had married for the second time. She got married to an uncle of mine, who was a widower too, and had three children; my aunt only had one daughter. She was a Spanish citizen, and during the war she was taken to the concentration camps from where she thankfully returned.

My aunt lived somewhere else with my uncle whose health was fine, but he usually didn’t come around the house so much. When my father died she came around the house and my mother knocked on the floor and called Miss Carina to read the coffee. She came up and started telling my aunt that she had one daughter, who lived far away. And indeed she lived in America. Then she told her that she had a husband, who was not ill but was going to die in three or four…

My aunt didn’t know anything about coffee reading, so she asked her what did that mean, and she replied it wasn’t years or months, but either weeks or days. So my aunt was wondering because everything else Miss Carina had told her was true. When she left, I was sitting there with Mother, thinking about what she had told to our aunt. Anyway, three days went by and all of a sudden we found out in the morning, that Uncle had died although he wasn’t sick at all. So we freaked out, and we thought of the coffee-reading… That’s why I am telling you, I believe it.

One other time we had gone over my brother-in-law’s house, the one who was from Kavala. He had come over Thessaloniki to study, but he didn’t study in the end, as he worked in his father’s shop, where everything was wrecked from the war. So Miss Carina came for a coffee reading.

He was about to go to report to the army, so she said to him that he didn’t have any roots there. He knew that he had to go to Alexandroupoli [city in Northeast Greece at the border with Turkey], and he was wondering whether he was going to permanently stay there, and get married and have children there. What Miss Carina was telling him sounded very strange to him.

A law came out then, which said that any Jews who want to can take the Israeli citizenship and resign from their Greek rights, which meant they would be relieved of their army duties and that they would immigrate to Israel. So he took advantage of this and went. Now, how could she have known that? He didn’t even know. You see, sometimes people say that through the questions they tell you the reading, but this one with my uncle, no one could have known.

One of my mother’s sisters lived close to our house and her husband used to teach us German and was a work associate of my uncle. Her house was architecturally Turkish and had a Turkish bath. We had the European-style bath in our house, the water would heat up and would fill the bath, only it wasn’t a built-in bath, it was a free standing one with little legs. That’s what was common at that time. My mother really liked the Turkish bath so she would take me and we would go around to my aunt’s house.

This aunt of mine was fat and had very large breasts. Her husband liked to joke, and when I was becoming a lady he would tease me and I would blush. He would also say to me that soon I would fall down the stairs and be full of blood. By that he meant my period. But, of course, I didn’t understand what he meant back then, so I kept replying to him, that I was careful and I wouldn’t fall.

My aunt had a son and a daughter. Her daughter was married and had two children. None of them came back [that is, didn’t survive World War II]. Her son didn’t marry because he really liked me. I didn’t like him but I was discreet. He went to the concentration camps too and never came back.

My uncle who had that school I mentioned earlier was married twice. He was widowed by his first wife with whom he had a daughter and a son. His daughter had a great voice and had gone to Paris for recordings. She even had a very artistic name; she was called Roza di Fiore. When she came back she became a music teacher. She was very beautiful. My uncle remarried and had another daughter, who was a great girl but wasn’t pretty because she had a problem with her neck.

When I got engaged to my husband, I could see that everyone around me had three grandmothers. The same was the case with my husbands’ family. So I used to say that I will die and he will remarry. I had even chosen who it will be, but these things are up to God.

I was the only daughter in the family. My father owned a shop and cooperated in many other businesses that held balls to reinforce their unions. There was this very beautiful hotel by the sea, the ‘Mediterranee,’ which was the best hotel at that time.

My brother had studied to become a mechanical engineer in France, so he associated with the state. When they declared war, he served as an army officer. He specialized as a minesweeper. He did all the plans for the Thessaloniki station.

My brother got married to an English Jew, who came to offer help after the war ended. They later left for England, and in fact, when I had my first heart operation, we stayed at their house in London. He was offered work in America and Israel. His wife was a Zionist so she grabbed the chance and they went to Israel. I used to be escorted by him at balls while he was an army officer.

This clock over here was given to me by the head accountant who was taking care of our shop at the beginning of the war; my daughter Sarah is much attached to it.

We had no idea what had happened in Thessaloniki during the war. Later, after the war ended, we found out what had happened with our families and friends. We even thought of going back because we saw people from Kavala coming to Athens, where we were starving, and they seemed in a better situation. At some point my husband was thinking of taking goods to go and sell them and bring back food. But something happened which stopped him, which was better because he wasn’t cut out for trade.

During the civil war 17 we had no participation, we were already in a bad position to get involved. Both my brother and my brother-in-law had gone to Israel.

When my father died, my mother came to Athens. We lived in Kalithea at the time. That’s where Sarah grew up and went to school. We later moved to Kipseli [highly populated residential area of Athens] and lived in a house on Kipselis Street, on the square. It was a nice, large house, and below it was the Rex Café. We later moved to Alexandras Avenue. It was the apartment of a friend of ours. He lived nearby. Below our house was a sweet shop.

One time we went to Switzerland on holidays with the kids, but my husband wasn’t very keen on going on vacation.

After the war we made many new friends, both Jewish and Christian. In Thessaloniki I had two friends, who were both working as secretaries at the university, Adigoni and Mary. I used to call them Maya and Yoyoni. They were my closest friends. They would come around the house for a visit. I didn’t have Jewish friends that I was so close with. Later, in Athens, there where so few Jews and we lived so far away from one another that again I had Christian friends there too. In our first neighborhood in Kalithea, we got very close with that couple that I mentioned before who didn’t have any children.

Sometimes we still speak in Judeo-Spanish with my Jewish friends. I have one friend who always wants to speak the language with me, and another one who speaks it only when she doesn’t want other people to understand what she is saying.

As I told you earlier, my husband was working at the Commerciale, but one of his friends convinced him to open a business with him, so he left his job without any compensation, at his own will. So he opened a business with his friend, who didn’t do business in a very clean way. My husband wasn’t used to dirty business, they had an argument and he left. But he wasn’t the kind of person who would go out looking for a job, so he didn’t work for a year and we were spending our savings.

He later became an associate of a distant relative who had a tourist booking agency. He put some money in and he liked the work. But his associate was planning to leave for America, so he left him. My husband wasn’t cut out to work in trade. He wanted to be correct in everything. Unfortunately he got into the trade business.

Greece was in an awful situation at the time, there was no money coming in, no tourism. When the dictatorship started in 1967, they were coming from the large hotels in town, asking us if we had someone to send them, while before that we had been asking them for shelter. In the meantime my husband had broken his leg and had surgery, which went wrong and as a result he was paralyzed. I had heart problems, so every now and then I would faint in the middle of the road. I was responsible for picking up the foreigners from the airport and transporting them to their hotels.

Sarah had passed her exams at the pharmaceutical school in Thessaloniki; she didn’t think she would. She had applied in many different schools. She was very excited that she had passed and decided to go. At the same time my second grandchild was born in Paris, so I had to go and help my daughter-in-law.

My son finished elementary school here. We were planning to go to Israel. There was a school in Israel and we decided to send him there. In the summer he had gone to this summer camp and in a contest he had won a tallit. We went to the school with my husband to the supervisor to give her my son’s clothes, so he takes the tallit out and asked me, ‘Ma ze?’ – What is this? I lost it and thought, we’re in Israel and my son doesn’t know what a tallit is. I couldn’t get over it. Anyway, I explained to her that he had won it in a contest, and he put it back inside.

It was the school of agriculture that organized these camps, and the children were learning other languages there too. My son had finished elementary school and he already knew French and English very well. He learned English there. The school was located in the border region, and every now and then Arabs would come by and there would be stabbings, so we were very upset. We couldn’t calm down. They were also teaching them how to hold a gun in order to be able to defend themselves.

We decided to bring him back, but he had already lost two years of school, so we sent him to a school in Lozenge, which was for very rich people. He probably thought that his father had oil companies or something because he kept asking for money to go skiing, etc.

We found out later that he wasn’t doing so well, so we brought him back here and he went to the French school here to obtain the Baccalaureate. Later he went to study in France, and in order not to send him to Paris, we sent him to Caen, that was in 1956. My husband had an uncle in Paris, his mothers’ brother, and we first went there and later to London, for my operation.

At the same time, my son met this girl that he was crazy about, and he said that he didn’t want to study anymore. Suddenly he stopped replying to our letters and only asked for money. So my husband, as he always did in difficult situations, sent me over to see what was going on. I went but didn’t find him where he used to live, at the university campus. I asked around and they told me that he hadn’t come around for days, so I burst out crying and went back to the hotel.

At one point, through a friend, I found out that he was ill and that the parents of the girl were taking care of him, so I sent word to him.

He said to me that he really wanted to marry her, so I was asking how they were going to live on their own. He said they were going to live in one of the French settlements, and with having the Baccalaureate he will become a monitor. She had gone to a commercial school and had become an accountant. You can imagine what I went through. He was the only man in the family, and I was crying for days, but in the end I was forced to agree. I met her in the end, and her parents, and gave her my consent to get married to my son, and decided to see what they were going to do next.

My husband broke his leg once and was at a Jewish hospital. The name was Cohen and he did physiotherapy and recovered. But after a while he broke his leg again. One day, when it was raining heavily, one our employees called him and said that he had a customer who wanted to buy a ticket for multiple destinations, and he didn’t know how to do it. So my husband got up regardless of the rain to go there.

At the time I was getting ready to go to Israel. At some point the phone rang and they tell me that my husband is at the Social Security Service, I.K.A., and that he is injured. As he was walking down Alexandras Avenue and was crossing over to Mistoksidi Street, at the corner, an army bus that a soldier was driving carelessly ran by, hit him and left him there.

My husband, instead of turning the driver in and saying that it was his fault, said it was bad timing, that it wasn’t the boy’s fault. The lawyers didn’t use the facts very well either. This second time that he got hit, he got a bad infection. Olympic Airways offered to transfer him, as they knew him from doing business with him. They made a bed and we went to Israel. There was this Jewish organization that covered all the medical expenses, but the infection was getting worse, and in the end they had to cut his leg off. He eventually died.

I go to the Jewish museum only three times a week now. I usually go on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. I don’t cook anymore, the girl that helps me does. I don’t cook kosher Jewish food, but I make eggplant with cheese.

I play scrabble with Zaklin. She is a special case. She is from a village in France on the border with Germany. She got married to one of my husband’s friends from childhood. His name was Morris Inkra. They were very close with my husband; they went to the Lycee together, I met him when we got engaged.

When the war started he got caught and was a prisoner of war. When Mussolini fell, they went to Switzerland and as they were prisoners of war they received packets from the Red Cross. He was one of very few people who knew French. They used to send him to get the packets from the Red Cross, and he got his bride from there too, so to speak.

He wasn’t very religious but he told her, to marry her she would have to change her religion and become Jewish. She agreed and they went to the rabbi in Geneva. So he said to him, ‘Look I am Jewish, and I want to marry her, but she is Christian. I want you to make her a Jew so I can marry her.’ ‘What?’ he said, ‘look I have three daughters, choose which one you want and marry her.’ But he wanted her, so they went to another city, I don’t remember where, to find a rabbi who would teach her and turn her into a Jew. She knows the religion better than me because she was even given exams on it.

When they came to Greece, they stayed in our house in Athens. He left his wife with us and went back to Thessaloniki to find out what had happened to his assets. When he got there, he knocked at a neighbor’s door. When she opened and saw him, she immediately tried to shut the door in his face. He had caught a glimpse of some of his own furniture in her house, and he managed to put his foot in the door, so she couldn’t shut the door.

So the woman tells him, ‘What do you want here? How come you weren’t made into soap by the Germans? And why do you come to us asking for things, I have nothing.’ When he heard that, he lost it and left. He broke down crying. As he was leaving, he heard a voice coming from the basement calling him, and he went towards the voice. ‘Hey young man, weren’t you living in this house?’ ‘Yes,’ he replies and gives him a tea pot with a cup of tea.

These things are in the museum now. In situations like this you see what people are really made of. So we have been great friends from the first time we met. Then we lost trace of each other. Each one of us had their own problems. We had many, she had some too. Then my husband died, and then hers did too.

Glossary