She has quiet gentle manners, a clear mind and a bright memory.

She speaks slowly due to her stuttering since childhood. She is taciturn and not emotional.

She says she devoted her life to work.

Her husband Isaac Verkhovski died in 2002. She lives alone in a three-bedroom apartment near the State University in Moscow.

Her apartment is very clean and cozy. Her husband Isaac Verkhovski was a stage designer.

He had a collection of folk craft items: brightly painted Zhostovo trays.

[1]They are placed on the walls and there are also pictures and drawings by famous artists that have been given to him.

Rachil Meitina has no problems with her day-to-day issues. She has a housemaid from ‘The Hand of Help’, a Jewish Public Charity Fund’.

This woman cleans her apartment. Her son Gleb Verkhovski often visits her, too.

She willingly gave this interview. She enjoyed talking about her life and hopes the story of her life will be remembered by her son and grandson.

My family background

My paternal parents lived on Zadonovska Street in the suburb town of Vitebsk 2. My father’s parents died before I was born. All I know about my paternal grandfather is that his name was Moisey Meitin. My parents didn’t tell me anything about him. He probably died when my father was just a child.

In my childhood my parents often took me to Vitebsk in summer. Vitebsk is a lovely town on the Dvina River, about 450 kilometers from Moscow. It is a very green town. There is a nice historical museum housed in the former town hall building. There was a Polish and a Belarus population in Vitebsk, but the majority of the population was Jewish. There was no Jewish neighborhood or district in the town: Jewish houses neighbored upon Belarus houses and this caused no problems whatsoever. People respected the traditions of other nations. My husband, who was born in Vitebsk, told me that his family lived in a communal apartment 3 and their neighbors were a religious Russian family. Their neighbors prayed for them and brought them Easter bread on holiday. They were friends.

My father’s parents were middle class, as they would say nowadays. I guess, they were involved in crafts and one of them had something to do with medicine. My father’s parents must have been religious people. They attended the nearby synagogue in Vitebsk.

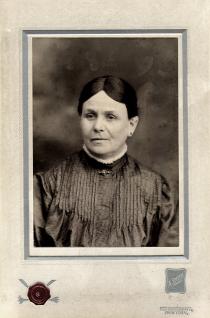

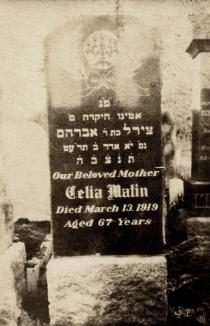

I know very little about my paternal grandmother Gelia Meitina. I have her photograph. She had a beautiful and intelligent face. She was born in 1852 and died in New York in 1919. She emigrated to New York with her four children before 1915. My father didn’t want to go there since he was actively involved in the revolutionary movement here in Russia. My father Tsala Meitin was a member of the Bolshevik Party, propagated revolutionary ideas and was even exiled for this to the town of Beryozov, about 2,000 kilometers from Moscow. [Beryozov: a town in Tobolsk region, exile destination at the beginning of the 20thcentury]. Inmates in Beryozov called him Alexandr and when he obtained his documents later he had this first name written in there. He was exiled in 1905 during the tsarist regime and served his term until 1917, the October Revolution [see Russian Revolution of 1917] 4. My father finished cheder, but didn’t continue his studies in any institution afterward. He was self-educated but an intelligent man.

My grandfather and grandmother had five children: three boys and two girls. Regretfully I can’t tell you their names or dates of birth or death. I remember one of them well: Aunt Rosa. She had a son, but I don’t remember his name or any details about him.My parents corresponded with him, but at some point they stopped corresponding. My father had two brothers, Ruvim and Mosha, and another sister, whose name I don’t remember. My father was born in 1878. He was the second oldest brother in the family. Ruvim was older and Mosha or Moila – that’s how his family addressed him ‑ was younger than my father. 5I remember that they sent dollars when Torgsin stores 5 were opened6. These stores sold food products and other goods for dollars while other stores only accepted Soviet money. I remember that our parents bought my sister a coat with a white collar. My father corresponded with his brother until theearly 1930s when it was allowed. After 1937, when the political situation in the Soviet Union was strenuous [during the so-called Great Terror] 6, correspondence with relatives living abroad was dangerous and my father stopped writing to them[see keep in touch with relatives abroad] 7. He must have been afraid of being arrested and destroyed their photographs. The only photograph I have is of my grandmother and her grave. My father didn’t tell me anything about his mother, brothers or sisters. We lost track of them.

My mother’s parents lived in the village of Kazarnovichi near Vitebsk. My mother was born there in 1883. Later her family moved to Vitebsk where they lived on Smolenskaya Street in the center of town. I know very little about my maternal grandfather. He died before I was born. I think he died during World War I. They told me he was very greedy. He literally starved to death on bags of food stocks. His name was Morduch Kazarnovski. He was born in Kazarnovichi, but I don’t know the dates of his birth or death.

My maternal grandmother’s name was Feiga Rokha Kazarnovskaya. I was named after her. She died shortly before I was born. It probably happened in 1917.She was also born in Kazarnovichi.near Vitebsk. I believe she was born in the late 1850s. My grandmother had a younger sister, Esfir. She married Ruvim Okunev, a Jewish man. She died shortly before World War II. They had four daughters. Her older daughter Sophia was my husband’s mother. She was born in 1891 and died in 1968. The second daughter’s name was Mary, born in 1892. The third daughter was Anna, born in 1894. And there was another Sophia. Probably, one of the girl’s name was Seina in Yiddish, but when they changed their names to Russian ones [see common name] 8 they both happened to have the name of Sophia. She was born at the beginning of the 20thcentury and died in 2001.

All of them finished grammar school. Mary moved to Kaunas before World War II [see Great Patriotic War] 9. When Germans occupied Lithuania she ended up in a ghetto. Mary had two sons. One of them was a talented violinist. Both sons must have escaped from the ghetto, but they perished somewhere since they never showed up again after the war. Mary survived. After the war her sisters took her to Moscow where they moved to after evacuation. The sisters were accommodated well there. Anna was the secretary for the Chief Prosecutor of the Soviet Union for many years, Sophia junior was the secretary for the Chairman of the Moscow Council and Sophia senior was a teacher of mathematics.

My maternal grandparents were religious. I don’t know any details since it was only my parents who told me about them. They had two daughters and a son: Frada, my mother,,born in 1883, Dvoira, born in 1890, and Isaac, who died in infancy.

My mother’s sister Dvoira Kazarnovskaya lived in Vitebsk. She married David Levitan, a Jewish man. He was a well-known attorney in Vitebsk. During the period of collectivization 10 he saved many people from dispossession [see Kulak] 11. I saw them bringing him food products to thank him for his services. I remember once we spent our vacation in the house of a man that my uncle had saved from dispossession.

When she got married Dvoira Kazarnovskaya became Vera Levitan. They had a son named Alexandr, born in 1908, and a daughter Sophia, born in 1910. Dvoira was a pharmacist. She worked in a pharmacy in Vitebsk. Before the Germans occupied the town during World War II Dvoira and her family evacuated.After the Great Patriotic War they didn’t return to Vitebsk, but stayed in Sverdlovsk [present-day Ekaterinburg] where they had been in evacuation. We corresponded with them occasionally: we sent greeting cards for holidays and birthdays. Dvoira died in 1990 at the age of 100.

Her son Alexandr was a promising surgeon. During World War II he was a surgeon in the army, but since he was a weak person and had access to drugs he became a drug addict. He died in Leningrad in 1950. Her daughter Sophia was a lawyer. She married Felix Kaminski, a Jewish man, who was arrested and executed in 1937. Their son Edward Kaminski is a correspondent member of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Sophia died in Moscow in 1985.

My mother finished lower secondary school and the medical/obstetrical school in Vitebsk. She entered a medical college in Petrograd, but quit after finishing her 2ndyear when I was born. My mother was also interested in politics when she was young. She was a member of the party of Mensheviks 12. She told me little about it, but I know that she even went to Geneva to a meeting with the Menshevik Party leaders: Plekhanov 13 and Martynov 14. She also went to meet Lenin in Paris, but I don’t know any details, of course.

My mother and father met in Vitebsk, probably during some [revolutionary] activities,that they were both involved in. They got married in Vitebsk in 1912. I don’t know whether they had a wedding at the synagogue or just a civil ceremony at the registry office. I know that they were both atheists. My parents’ mother tongue was Yiddish, but they always spoke Russian. They switched to Yiddish when they didn’t want their children to understand the subject of their discussion.

My parents moved to Petrograd in 1916. The name of this city changed to Leningrad in 1924 and now it’s called St. Petersburg. I don’t know why my parents moved – probably because this city was the center of revolutionary activities. My parents rented an apartment and my father went to work as a typesetter in a printing house called Printing Yard. My mother was a medical nurse in a town hospital.Around this time my parents changed their Jewish names to Russian ones: my father became Alexandr and my mother became Fania Meitina.

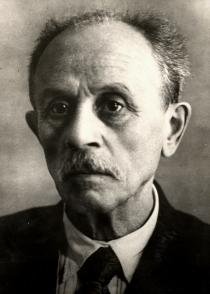

In 1917 my father was mobilized to the army. I know very little about this period of his life. I have a photograph from the time when he was in the army before the Revolution of 1917. He served in the tsarist army that didn’t exist any longer after the Revolution. My father returned home because of the Revolution.

Growing up

My sister Vera Meitina was born in Vitebsk in 1912. I was born in Petrograd in 1918.

My parents received a very nice apartment in a very beautiful pre-revolutionary building in the center of Petrograd. There were six rooms in the apartment. We used only three of them and our housemaid lived in another room. Two rooms were locked. There was a toilet near the kitchen and another one next to the bedroom. There was a wood stoked stove and also a Primus stove used for cooking. There were beautiful stoves for heating the rooms. Our janitor Alyosha brought wood for stoking the stoves. There was running water in the apartment.

I had many toys. My father loved me a lot and always bought me toys. I remember my father saying that I had 24 dolls. The other three rooms in our apartment were called ‘cold rooms’,since they were not heated in order to save wood. My parents dressed me in warm clothes and we went for a stroll there. Later some students rented those rooms. In 1927 this apartment was divided into two. They made a kitchen in the hallway, a bathroom and a toilet and separated three rooms from us. Another family lived in this apartment – they had their separate entrance. Our apartment belonged to a scientist in the past. Before I was born his family left Russia for Prague. My older sister told me that their son came to pick up some of their belongings. This ex-tenant left a huge collection of books. I maintained a book log where I registered each book that members of our family took from there. I was like a librarian. My parents, my sister and I read books from this collection. There were Russian classics: Turgenev 15, Pushkin 16 and Dostoevskiy 17.

My parents had housemaids. When I was small I had a nanny.

Her name was Kamilla and she was a Chukhon woman 18.

Another Chukhon woman brought us milk. She lived in the suburbs of Leningrad.

She perished during the blockade of Leningrad 19 during World War II.

My father was very cheerful and witty. He was the heart and soul of all gatherings. He was very sociable and easy-going. He was very intelligent and well read. It was amazing considering that he actually only had elementary education. He wasn’t strict with the children. When we lived in Petrograd he and I were called ‘Papa, buy’as a joke, since I was always asking him to buy a toy. He never turned me down. I think he had an influence on us. My sister and I made our way in life. He helped me a lot when I was working on my candidate’s dissertation. He typed the first draft.

My mother obviously liked my sister more. She was never satisfied with me and constantly reproached me with her ‘she can sew’, or ‘she is so handy while you aren’t’. The only time I heard my mother praise me was when I defended my thesis. My mother called her friend and said ‘Rachel has defended her thesis today’. This was the only time in my life that she complimented my achievements. She was strict and greedy. Her father was greedy and she probably took after him, as well as my sister and her son. My mother was prudent. She was a cold person. I was never as close with my mother as I was with my father.

Our parents had many friends that often came for a cup of tea. They had a discussion and the children played in another room. I remember Christmas trees that we decorated in Petrograd. We celebrated Christmas and Easter. I remember a wooden bowl with the letters ‘CR’ [Christ is Risen] engraved on it. We didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays, but I remember that gefilte fish was made whenever our friends and relatives visited us on Soviet holidays, birthdays of family members and even at Christmas. Most of my parents’ friends were Jewish. My friend from that time had a Jewish father and a Russian mother. When another family moved into our apartment, after it had been divided into two, we became friends with them. There was a boy of my age in this family and I remember his mother taking the two of us to the Botanical Gardens. We were friends with our neighbors, although the door separating our apartments was always locked.

My mother and father spent their vacation with the children at the dacha[cottage]. When we lived in Petrograd we rented a dacha on the bank of a lake somewhere in the suburb of Petrograd. We had a boat and went rowing on the lake. We often went to visit our parents’ relatives in Vitebsk. In summer 1934 we stayed in Shpili near Vitebsk. I think now it’s a suburb of Vitebsk. There were many apple orchards there. It was a lovely spot. I remember the sound of apples hitting the terrace of the house where we lived: sweet small Belarus apples. That summer the family of my future husband Isaac Verkhoski lived there, too. He is my second cousin. His mother Sophia Verkhovskaya and grandmother Esfir Okuneva were there, too. That was when I met him and we made friends, but many years passed before we got married. There are no relatives of ours left in Vitebsk.

Our family was rather well off. Although my parents took an active part in the revolutionary life of the country when they were young they became rather neutral later. They didn’t discuss any political subjects with me and didn’t share with me their attitudes about what was going on. However, they were interested in the events. My father used to say, ‘When I die please come there and tell me what is happening in the world’. Fortunately, Stalin’s terror didn’t impact my parents.

I spent my early childhood in Petrograd. I recall this town as a fairy tale. I found it very beautiful. There was a nice yard with a garden in it. We lived on a quiet street. There were stores and schools on the nearby lanes. My sister studied in one of them. Matveyevskaya church was on our street. It was demolished in 1930. We had already left for Moscow by then. There were synagogues in the city that I never went to since it wasn’t a custom in the family. They were destroyed in the 1930s when the authorities struggled against religion 20. It was a clean town with numerous private shops. I remember the period of the NEP 21 when stores were full. I remember delicious chocolate. My mother gave me some change and I bought a chocolate teddy bear.

At the age of five I went to a state budget kindergarten near our house. The director of this house was a scientist in the field of pedagogy whose name I don’t remember. We learned music and dancing and had other classes. It was a very good kindergarten. I went to a Russian school in Petrograd and also attended a nearby music school where I learned to play the piano. I studied for three or four years in the music school.

Lenin died when I was six years old. I remember that my father and I went to Troitskiy [Trinity] Bridge where we could hear gun shots from the fortress. There were crowds of people and the traffic stopped. I was too small to grasp the importance of the event, but I understood that something terrible had happened.

In 1924 the printing house was closed and my father lost his job. He went to Moscow looking for work and we stayed in Leningrad. My father met an acquaintance of his in Moscow. He offered him a job as a corrector in the committee for standardization and development of state standards that had just been established. Later my father became a technical editor. My father rented a room in a house in the very center of Moscow. We moved to Moscow in 1930 and got accommodated on Kropotkinskaya Street. We exchanged our huge apartment in Leningrad for a small two-bedroom apartment, about 27 square meters, in Moscow. There was central heating and gas in this building, which was very rare in Moscow in the 1930s. There was also a bathroom, a toilet and a small kitchen in the apartment. In my class I was the only one living in an apartment with gas and heating. My mother went to work as a medical nurse at the medical facility of the University of Working People of the East and my sister entered Chemical Technological College. I was getting acquainted with Moscow. I used to take a tram to tour the city. I got used to Moscow, but I always liked Petrograd better. I still have warmer feelings for Leningrad than for Moscow.

My mother couldn’t afford to pay for my musical education any longer. We were pressed for money. My mother and father’s relationships also changed for the worse. My father must have met somebody when he was alone in Moscow and didn’t terminate these relations. My sister told me later that she asked our mother why they stayed together and my mother said that my father didn’t want to leave his children.

I studied in school 22, a former grammar school, in Moscow. A few years ago it celebrated its 75thanniversary. Many of our teachers used to teach in this former grammar school. I remember Sergey Fyodorovich, our teacher of mathematics. He addressed all his students with the formal ‘You’. Our teacher of physics was the author of a textbook in physics and our German teacher Albina Ivanovna was a teacher of the former grammar school. I had good marks at school. I was good at biology, but didn’t have any favorite subject at school. I had many friends. There were more boys than girls in our school. We kept in touch after we finished school and we are still in touch. There were Russian and Jewish children, but we didn’t care about each other’s nationality then. It was of no importance. We didn’t face any anti-Semitism, but I think there was some when looking back. I had a friend, Dima Zotov, a Russian boy. Our friendship stopped all of a sudden when we were in the 9thor 10thgrade. Now I understand that it must have been his strict mother that forbade him to have a Jewish friend.

I became a pioneer at school. It was a routinely matter for me. I wasn’t an active pioneer. I remember we went to parades on Soviet holidays. The Iskra newspaper printing house was a patron organization supporting our school. Employees of the printing house went to parades with us. We got together near the printing house and marched to the Red Square. It was fun. There was a brass orchestra playing and we danced and sang.

After finishing school I decided to continue studying sciences related to chemistry and biology. I could take a tram that turned left to university or another one that turned right to the College of Fine Chemical Technology. Both institutions weren’t far from where I lived. The first tram that came to the stop was the one turning left, so I entered the Faculty of Biology of Moscow State University in 1936. I enjoyed studying there. There was no anti-Semitism. The dean and deputy dean at the university were Jews. Jewish scientists were lectures at the university, but later the situation changed.

My specialty was the physiology of animals – biochemistry. My group was the best of the faculty and university. We were awarded two red banners for our academic success at university. It was a big honor. I studied well. I didn’t look my age when I was a 1st-year student. I remember my exam on morphology of plants. I wore a plain polka-dot dress with a white collar. I noticed that our teacher gave me a ‘5’ and a smile spread across my face. The teacher asked, ‘How old are you?’ I said, ‘19’, although I hadn’t turned 19 yet. He looked at me and said, ‘Well, at your age it is all right to be pleased with a mark. You won’t when you get older’. I wrote an interesting diploma thesis. My tutor was a professor, a scientist of the institute of biochemistry. This thesis actually became a part of the scientific work for which this institute received a ‘Lenin Award’ 23.

My friends were Mila Ginzburg, Ruth Berkman, Nina Gelmanand Shura Tseitlin, all Jewish girls. The only Russian girl was Natasha Melitsyna, the daughter of a well-known professor of medicine. We were always the first to take any initiative and we were called ‘presidium’. I joined the Komsomol 24 in university. I spent all my time studying and being involved in students’ scientific activities. I didn’t take part in any public activities.

1937 had its impact on the university. Some outstanding professors and students disappeared. I remember a meeting where a student was expelled from university because his father had been arrested. I felt awkward at this meeting. I knew that he wasn’t to blame for his father’s ‘sins’ and that he was suffering already – so why add to his suffering? My father told me about the legal persecution of leaders of the Party. He understood that not all of them could possibly be ‘enemies of the people’ 25, but he never discussed this with me.

My sister graduated in 1936 and got a [mandatory] job assignment 26 at the Scientific Research Institute of Glass where she was involved in scientific development. She defended her candidate’s dissertation in 1950. She met her future husband Pavel Prushak, a Russian man, when she was a student. Upon graduation from college he was a teacher at school. They got married in 1940. They had a civil ceremony, but no wedding party. It was the custom at the time. They lived in his room in a communal apartment in the center of Moscow. In January 1941 their son Leonid Prushak was born. My mother left her job to look after her grandson. She never went back to work.

During the war

In 1939 when I was a student at university a pact with Germany was executed [see Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact] 27. I didn’t think that there was to be a war. On 22ndJune 1941 I passed my last exams. The beginning of the war was quite a surprise for me. It was a warm day. My sister took her baby son for a walk when she heard about the war on the radio. Shortly afterwards her husband was mobilized to the front. He perished at the front in 1942.

Upon graduation from university I was going to work at the biochemical laboratory in a children’s hospital in Moscow where I had some training during exams. I went to this hospital, but it had already been turned into a military hospital. Well, I had to think about my mother and sister and her baby. We evacuated to Kineshma, about 350 kilometers from Moscow. My father stayed in Moscow since the institute where he was working stayed there, too. He stayed there until September 1942 when the Germans came close to Moscow and panic began in the town. He joined us in Kineshma and stayed there until he was called back to Moscow.

We decided for Kineshma since our friend from Leningrad was there. My friend’s father had been arrested in 1937. Her father’s investigation officer had notified the family that they would be ordered to leave Leningrad within 24 hours in a few days. He advised them to think about a town where they wanted to go. They decided for Kineshma in Ivanovo region. My friend Galia Lifshytz was a student then. There was a technical college in Ivanovo and a chemical and ceramic plant and she thought that she would study and then go to work. This was in 1938. I visited them several times there. It was a nice town.

When we came to Kineshma I went to the military registry office and they issued an assignment to me. I was to work in a hospital. There were many Jews in evacuation in Kineshma. The local population didn’t demonstrate any ill-mannered attitude. I worked as a lab assistant in hospital for two years. We worked from 8am till 8pm. We received a meal in the hospital and I even managed to take a bowl of shchi [cabbage soup] to my relatives. The family was having a hard time. We settled down in an empty house. Its owners had left.

My mother and sister didn’t go to work. My sister had a baby son to take care of. She sold our belongings at the market to get some money to buy food. Later my father, who worked in a printing house, began to send us paper that my sister exchanged for food products in a kolkhoz 28 on the opposite bank of the Volga. My sister crossed the river by boat in summer and in winter she walked on the ice. We survived and two years later my father sent us a document enabling us to return to Moscow. We returned to Moscow in 1943. Moscow hadn’t been bombed, but there was hardly any food available. My father was very thin and looked awful. I hadesome potatoes and a three-liter jar of melted butter with me. I sat on the upper bench in the train the whole night holding it in my hands. When I returned my father and I went to the canteen at his workplace where we had nettle soup.

We returned to our apartment in Kropotkinskaya Street. My sister went back to work at the Institute of Glass and my mother looked after my little nephew.

I went to work at the biochemical laboratory of the central skin and veneorology hospital in Moscow. I worked there from 1943 till 1949. I defended my candidate’s thesis ‘Vitamin B and its influence on carbohydrate metabolism’ in 1949. We injected this vitamin into the brain of animals by the method of Lina Shtern 29 and watched how the skin was changing. This work also had practical significance: we offered treatment to patients by my method.

After I had defended my thesis I got an invitation from the Academy of Sciences.

They said my thesis was very interesting,

but that there were too many references to Shtern and they wanted me to cross out this name.

A professor, who used to be Shtern’s student and I sat down to do the corrections.

What else could we do? If we hadn’t done what we

were told the Higher Certification Commission wouldn’t have approved my dissertation.

A few days later it was approved. Shtern was a world-known scientist.

Employees of her institute were her followers and supporters. Later I attended a meeting

where an academician grabbed Shtern’s books yelling,

‘On our Soviet money! On our money they’ve published these books!’ throwing them off the stand.

In 1949 Lina Shtern and members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee 30 were arrested.

Her institute was closed, employees fired and another institute was created on the basis of the previous one.

The management of the institute where I worked was replaced.

The attitude towards Jews changed dramatically.

We were suppressed and abused.

There was such a hostile environment that we realized it was time to leave.

I submitted my documents to the biochemical laboratory of Vishnevski Institute of Surgery where I became a junior scientific employee. I was employed on 1stDecember 1949 and on 3rdJanuary 1950 I was fired due to reduction of staff; they explained to me that since I was a new employee it was all right to fire me rather than somebody that had worked here for a long time. However, it was crystal-clear that they fired me because I was a Jew. Other employees felt sorry for me. One of them was acquainted with Bakulev, who was opening a laboratory at that time. He began to study lungs and needed to learn about gaseous metabolism, blood gases. He needed employees.

Alexandr Bakulev was a famous surgeon. He was chief surgeon in the Kremlin hospital for many years and a full member of the Medical Academy of Sciences. He was the director of the surgical clinic at the town hospital; a very decent and intelligent man. He was a multifaceted surgeon. When I began to work with him he was organizing a lung department. In 1948 he performed the first heart surgery. He employed me. There were several broken units in the room where I was to work. They opened the door saying, ‘This is where you will be working’. I started work on 28thJanuary 1950.

I actually set up the laboratory that lay the foundations for the Bakulev Institute of Cardiovascular Surgery. I was one of its founders. I was head of the laboratory. I worked there from 1950 till 1989.

I met Isaac Verkhovski, my future husband, in 1934. In 1943 his mother, two aunts, Anna and Sophia junior, and he moved to Moscow. They lived in a room in a communal apartment. We met again on his mother’s birthday in 1948. We dated until we decided to get married in October 1950. We had a civil ceremony. Isaac was a designer and he was surprised at the dull interior design of this registry office. There were only dusty palm plants decorating the room. At home we had a small dinner. We settled down in my apartment on Kropotkinskaya Street. My mother, my father, my sister Vera and her son also lived there. There wasn’t much space.

Isaac Verkhovski was born in Vitebsk in 1919. His father Samuel Verkhovski was an assistant accountant before 1917 and after 1917 he worked in trade companies in Vitebsk. He died in 1935 and was buried in the Jewish section of the town cemetery in Vitebsk. His mother Sophia Verkhovskaya, nee Okuneva, was a teacher. She finished a grammar school and was very good at teaching. She lived in Vitebsk before World War II and during the war she evacuated to the Urals with her relatives.

After finishing lower secondary school in 1935 Isaac entered the art school in Vitebsk. He finished it in 1939. Afterwards he got a job assignment with the Lepesh regional theater near Vitebsk where he worked until the beginning of the war in June 1941. This was a traveling theater that was on tour in Western Belarus in 1941. He was chief stage and costume designer. When the war began the theater closed. They loaded all items on carts and walked beside the carts. My husband had a winter coat made in Belarus. It was a hot summer and he got tired of dragging this coat along. He threw it away. Since then he never had a winter coat made and did without. They got to Vitebsk and in some time my husband managed to evacuate with his relatives.

In December 1941 he was mobilized to the army. He was wounded in his right hand at the front and was demobilized from the army in 1942. In November 1943 he began to work as art director in the Moscow Jewish State Theater of Solomon Mikhoels31. My husband participated in making arrangements for the Freilakh performance and many other performances produced by Mikhoels. He did the stage sets and costumes for almost all performances staged by Mikhoelsin the theater. My husband worked with a well-known artist called Alexandr Tyshler 32. They were friends. In 1948 Mikhoels was murdered in Minsk. My husband went to his funeral and helped his relatives to make all necessary arrangements. Isaac was very sad about the death of Mikhoelsand the subsequent closure of the Jewish theater. He stayed in the theater until the last day and helped to save the stage sets. The Jewish theater operated until early 1950. In the same year Isaac began to work in Maly Theater 33. He obtained an assignment by the Ministry of Culture. He worked there for over 30 years until he retired in 1989.

Our family didn’t have much to live on. I received a salary of 80 rubles when I was a lab assistant, which wasn’t a lot of money. My husband received 60 rubles. We lived with my parents until my son was born. We gave my mother 100 rubles of housekeeping money every month and had little left. My mother wasn’t really fond of my husband and that was mutual. My mother believed that I deserved better while my father was easy about it. In 1954 my husband mother’s sisters insisted that my mother-in-law lived with us. She was living with her sisters in a room in a communal apartment up until then. Living with my mother and mother-in-law under one roof wasn’t easy.

After the war

Well, in 1950 I joined academician Bakulev’s group. I was senior lab assistant.

Senior lab assistant was a low position, the lowest one for a person with higher education and I was already a candidate of medical sciences. Later,

when we had our laboratory equipped my boss introduced me as our senior lab assistant and head of laboratory. I had a low position and a small salary because I was Jewish.

Once in early 1953, when the Doctors’ Plot’ 34 was at its height, I got a telephone call from the academy.

They notified me that I was fired due to reduction of staff in Bakulev’s group. I and another woman were fired. She was Russian, but her husband, a well-known physicist, was a Jew. The next day my manager went to see Bakulev. Bakulev had the habit of leaving town when something like this happened. My boss returned and said that Bakulev told him there was nothing he could do at the moment. My husband became the sole breadwinner in our family.

In 1952 my father lost his job. He worked at the editorial office of a scientific research institute for over 30 years. He was one of their best employees. He began to work for free at the library near our house. My sister, who worked at the Institute of Glass and defended her thesis, was also fired. Our family of six lived on my husband’s small salary. It was very difficult. We could hardly manage to make ends meet.

On 5thMarch 1953 Stalin died. We had idolized Stalin during and after the war, but at that moment we already understood that he was to blame for the suppression of Jews. His death was a liberation. On 6thMarch my boss called me and told me to come back to work immediately. My colleagues told me that Bakulev adamantly demanded that I returned. I held the same position, but soon I became a junior and then a senior scientific employee. Then I became head of the laboratory. Some time later my sister also resumed her job.

However, Stalin’s death didn’t put an end to the persecution of Jews. I had almost an analogous story with my doctor’s dissertation that I defended at the Academy of Medical Sciences. I got all votes ‘for’ it. I was approved by the first council of VAK certification commission: the highest body of federal executive authority awarding titles, the Russian equivalentsof PhDs, MAs, etc]. Then another council was conducted. Somebody told me that a professor didn’t like my surname and demanded an additional reference for my work. Once an acquaintance of mine called me to say that her neighbor, who was a well-known scientist, had got my dissertation to write a reference letter. He said that he was unfamiliar with the subject and asked me to write a reference letter that he would sign. My boss and I wrote the letter and he signed it. On the next day my dissertation was approved.

My father died a sudden death of infarction in 1958. The day he died his colleagues from the library called to find out why he wasn’t at work.

After Stalin’s death he didn’t go back to work. They would have probably hired him, but he was over 75 years of age then.

He had never been late or missed a day at work. He was buried in the town cemetery.

My son Gleb was born in Moscow in 1958. Two months after he was born I went back to work. My mother and mother-in-law looked after him.

I worked a lot before and after my son was born. I specialized in pathological physiology. In the laboratory I worked on the issues of breathing, gaseous metabolism and gaseous content of blood. We examined hearts and often surveyed blood from various parts of the heart. I worked with patients with heart and lung problems that were later operated. My dissertation was entitled ‘Gaseous exchange and gaseous content of blood in patients with congenital heart diseases’. ‘This was the first dissertation on this subject in the Soviet Union. I’m satisfied with my scientific accomplishments since we were the first to do it and I provided assistance in establishing similar laboratories in a number of leading clinics of the country.

When I was promoted life became easier. A senior scientific employee received 400 rubles per month. This was enough at that time. I couldn’t afford to buy expensive things, but we were doing all right. We went to theaters, art exhibitions and concerts at the Conservatory. My husband was fond of ballet and we attended all ballet contests. We often had guests over at birthdays and on Soviet holidays. Isaac was a sociable man. His colleagues liked him. His friends were producers and artists of the Maly Theater. We liked to spend our summer vacation at the seashore in Riga, Latvia.

My sister married Valentin Estrovich, a Jewish man, in 1959. She bought a cooperative apartment for my mother and her son and lived with her husband. My mother died of a stroke in 1967. We buried her in the town cemetery where my father was also buried.

Recent years

In 1976 we moved to another apartment, which my husband received at work, and where I live to this day.

My son Gleb studied at secondary school. He studied well. He became a pioneer and a Komsomol member at school. He didn’t take part in public activities. He had many friends and was the heart and soul of any company. He probably took after his grandfather. We aren’t religious and never observed Jewish traditions and our son wasn’t raised in the environment of Jewish traditions.

Gleb failed to enter the College of Chemical Machine Building in Moscowthe first time. Perhaps, his nationality played a role. The following year Gleb had private classes with a teacher ofmathematics from that college. This teacher was also there during an exam. Gleb passed his exams, entered Moscow College of Engineers of Railroad Transport in 1975 and graduated in 1980. He never mentioned any problems regarding nationality in college. Upon graduation he got a job with the Moscow metro. He has worked in the laboratory of corrosion for many years. At night, when there is no traffic, they inspect the track for corrosion. He joined the Party at work for the sake of his career. He wasn’t an active party member. All he did was attend meetings and pay his monthly fees. His membership was over at the beginning of perestroika 35. By the way, my son was the only member of our family, who became a party member. Neither my father, a former Bolshevik, nor my mother, a former Menshevik, ever joined the Communist Party.

My son got married in 1980. His wife Irina Charskaya is a Jew. He met her at school. Their son Vitali Verkhovski was born in 1981. My son divorced his wife twelve years ago. She fell in love with another man, who emigrated to Canada. She followed him there alone. So, my grandson stayed here with his father. He finished 13 years of school and works in a bank. We never thought he would go to live there [in Canada]. My daughter-in-law’s cousin went on a visit there and took my grandson with her. When they arrived Vitali’s mother insisted that he stayed in Canada. It wasn’t his wish. He studied here in a good school where they learned English. I believe he would have got a higher education if he had stayed, but there in Canada it is very costly and besides, he isn’t eager to get it. My grandson has lived in Canada with his mother for eleven years now.

Well, I think emigration is a positive thing, but not always. My relative,my husband’s niece Inga Levit, followed her children and moved to Israel. She is better off there, but she regrets she had agreed to move there. I think it’s a good thing there is Israel, but if you take European countries Israel is like a backyard. A number of our acquaintances moved to other countries from there. I’ve never traveled abroad. In 1980 I got an invitation to hold a speech at a conference in France. I obtained a passport and got tickets. But at the last minute I wasn’t allowed to travel there. Again, the reason was my nationality.

I retired in 1989 at the age of 71. My boss had retired before I did and his replacement didn’t respect my accomplishments and honors. My former boss even said once, ‘You need to understand that Rachil and I were organizing things here, you just barged in’. I didn’t like working with him. It happened so that my boss died on the day I left my job. Actually, nobody pushed me to quit, but I couldn’t work with a person like my new boss.

I retired during perestroika. Perestroika didn’t bring anything good into our life. We lost all our savings that we had made for old age. Our society divided into the classes of rich and poor. My pension is too small to lead a decent life. It’s too bad that my husband and I have to rely on our son’s support when we had worked hard all our life. When my husband fell ill he needed expensive medications and medical care. If it hadn’t been for my son I wouldn’t have managed.

My husband fell severely ill in 2000.

I had to take care of him. It was exhausting.

He died in 2001. We buried him in the town cemetery near the graves of our relatives.

I think Isaac and I had a good life. We were different and had different professions.

However, we didn’t have major disagreements.

Although I earned more than my husband it didn’t disturb me.

My husband was an interesting individual.

Now I don’t work any more. I receive a pension of 3129 rubles, approximately $100 USD. It’s not a lot of money.

My son Gleb supports me. The Jewish Charity organization ‘Helping Hand’ provides medications for a certain amount of money.

They also send a cleaning woman once a week. I’m not a member of any Jewish organizations.

I don’t know Jewish traditions, but I identify myself as a Jew: I’m a Russian Jew. My father and mother are Jews and that is my nationality as well. I wouldn’t want things to be otherwise. I had problems in this regard, but it was the political situation in the country that allowed it to happen. I suffered a lot from having a Jewish surname, but I’m not ashamed of having it. I became a Doctor of Sciences and a respected person in my sphere regardless of any obstacles.

Glossary: