Rachel Averbukh

Saint Petersburg

Russia

Interviewer: Inna Gimila

Rachel Meerovna is a cheerful and active person.

She started our acquaintance with jokes and treatedingus to some sugar candies, and when we were about to say goodbye after our second meeting, shenarratetold us around fifteen "salty" anecdotes.

Her laughter is very sonorous musical and cheerful,and her voice has a very unusual and pleasant timbretone.

She possesses a pair of lively, clever and attentive eyes and a lucid mind:

she remembers everything, represents recounts everything perfectly, she is a woman,whomyou don’t need to extract words from – she is a wonderful narratorstoryteller.

She walks with a stick and a rucksack behind her shoulders. We were glad happy that we gave to please Rachel Meerovna with pleasure by making this interview with her. She had very kind words for our work.

Family background

I did not know either my maternal great-grandfather Vulf Berkal or his wife, whose name I don’t know. I only know that they were born somewhere in the Pre-Baltic region, in what today is Latvia. I did not know my great-grandparents on my father’s side, either. My grandfather on my father’s side, Yankel Averbukh and his wife, my grandmother Averbukh [name and dates of birth and death are unknown,] also lived in the Pre-Baltic area, in Lithuania.

My maternal grandfather, Leibe Vulfovich Berkal, lived in the Latvian city of Dvinsk, which now is called Daugavpils. My grandmother Hana Berkal (I do not know her maiden name), was born in the same Pre-Baltic area in the 1860s and died before the war in 1930 – I don’t know the exact date. I remember how both of them looked.

They came one time to visit us in Pskov from Latvia, to see their children and grandchildren, and I met both of them then. My mother and aunts told me about them. My grandfather was handsome, with a white beard. He was thin and of average height. He was very kindly, gentle and quiet, and he was also very religious. He was a shames1 in a synagogue.

He and my grandmother were quite well off financially. When he came for a visit, Grandfather Leibe prayed in our house every morning, and put tfilin on his arms.

Grandfather and Grandmother spoke to each other only in Yiddish. I understood everything perfectly. Grandmother Hana was a housewife, a very religious woman. They had a large family, six children. Among them was my mother, Tsitsilia Leibovna Averbukh, nee Berkal. She was born in 1883 and died in 1968.

In addition to my mother, Leibe and Hana had three daughters and two sons. All were born in Dvinsk in what today is Latvia: I know very little about them, but what I know, I will tell you. The eldest, Evsei, was born in 1884, lived in Pskov, and taught drawing at a school. He was an artist, and his wife was the director of a kindergarten.

Evsei fought in the war [1941-1945] as a soldier at the Leningrad front. He died in Pskov in 1970. His sister Berta was born in 1885, lived in Pskov, was a housewife, later she was exiled to the North with her husband for espousing Zionism2 , and died in Karaganda in 1950.

The next sister Ida was born in 1888, lived in Pskov and worked as a teacher and interpreter for the deaf and dumb in a Soviet school for disabled persons. During the war [1941-1945] she was evacuated with her family to Saransk in Mordovia, where she died in 1960.

Sister Polina [1890s-1960s, Moscow] was an economist. Brother Efim [1894-1957, Leningrad], a trade dealer and salesman, went through the blockade in Leningrad. I do not know which Jewish traditions they followed in their families, but I don’t think they were especially religious. You couldn’t be a religious Jew in the Soviet Union and have no problems.

Mother’s father Leibe Berkal went to synagogue regularly, and one time he saw a young man there whom he thought looked nice. He brought him home [to propose him as a husband for her]. Before that, they proposed a rich manufacturer to Mom as a husband, but she kept rejecting him. She was a virgin until she was 27.

Mom and Dad liked each other very much. But mother noticed that my father, Meer Averbukh, was not pious. On Saturdays, for example, he walked with a cane. [Using all sorts of devices and instruments – including a walking stick - is prohibited during Sabbath]. So she sent her father to the rabbi, to ask whether she could marry a man who did not observe Sabbath.

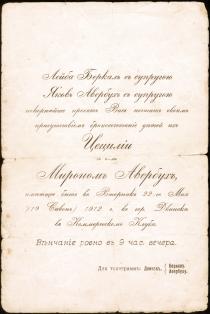

Rabbis were very clever people. This one said: Do what you consider the right thing to do, and God will take care of the rest. And this is how it all worked out. Mom and Dad got married in 1912, Mom was 27, father - 29.

In 1913 Mom gave birth to twin boys - but they died before I was born. Since then it has been common for twins to be born in our family. One of the twins died before he was one - he had a congenital heart disease. The other - Iosenka, (Iosif), was poisoned by fumes when he was 1 year and 10 months. The housemaid stoked the stove with scraps of leather and left. There were wall stoves in each room. Had anyone been at home, the boy could have been saved.

- Growing up

I, Rachel Meerovna Averbukh, was born in 1915 in Pskov. I was the sole and favorite child in the family. From childhood I had a teacher from the synagogue in Pskov, who came to our home and taught me to read and write. But he was an elderly man, and I didn’t like those lessons – you see, I was a small girl, 6-7 years old. I wanted to play, not study, and I refused to take those lessons.

I could read and write in Hebrew. And now I still know the letters, but I can only read the printed text, not the written Hebrew. I can speak the language all right, though.

In Pskov we lived in Arkhangelskaya Street, that was its name before the Revolution of 1917. It later was called Lenin Street, because Lenin lived there at one time. There is a Lenin museum there now. It was just a common unpaved street, along which there were wooden and brick houses where ordinary people lived.

The population in Pskov was mixed – Jewish families did not live separately from Russian families. The different national groups co-existed quite peacefully.

Daddy had a private workshop in the courtyard where he made leather upper parts for footwear. The workshop was in the courtyard in an extension of the next brick house, with windows facing Arkhangelskaya Street. We lived next door, also in a brick house, in a three-room apartment on the first floor. There was a bedroom, a dining room and a nursery. All the tenants in our building were Jews.

Even now I occasionally see a 90-year old woman here in St. Petersburg who lived in our house back then. I helped my father. He had a very heavy machine attached to the table that punched neat round holes in the leather and pressed iron rivets in them, to make eyeholes for laces in women’s shoes. I loved to use that machine. I also helped father cut the lining, watching that everything was done as accurately as possible.

Daddy only made the uppers, only the top part of the shoes; all the rest of the footwear, soles and heels, were made by the shoemaker. Mom and I both wore shoes made by father. On Friday, he used to come home at twilight and did not work until Sunday. Dad always knew that the dinner was exactly at 4 o’clock. No-one had to call him; he would stop working and come home for dinner, because the workshop was very close, right in our courtyard.

In the morning, Daddy used to pray in the dining room, putting on his Tfilin. We would not go in, so as not to disturb him. He put leather boxes on his arms. When he prayed at home, Daddy did not put on his tales, a large white silk scarf with black strips on the sides and fringes. He put it on only when he attended synagogue on the holidays.

As for toys, I had one favorite knitted doll, and a wonderful porcelain tea set for dolls. We had a grand piano at home, and I began to study piano when I was just a little girl. My teacher had studied with the great Russian composer Glazunov at one time. Our house had the usual furnishing -- wooden tables, buffets. Mom had a sewing machine, too, which she used often.

Mom gave me the job of setting the table for dinner. Every day I would cover the dining room table with a beautiful table cloth. Then I would ask Mom, what sort of dinner are we going to have today - dairy or meat? According to her answer I put out the right dishes. I remember very well that we had a buffet with two large sections, both of which could be locked with a key.

One whole section was filled with utensils for use at Passover - there were plates, spoons and forks. The other section held everyday dishes – those not used for holiday dinners. The cooking utensils were in the kitchen, but stored separately in different places. For meat dishes we would use certain bowls and pots, for dairy dishes – other ones. We certainly knew that for dairy dishes you were not supposed to use meat utensils and vice versa.

Mother’s brothers and sisters - my uncles and aunts – used to come and visit us. By then, Daddy had no relatives. Some time earlier his elder brother Rafail lived in Vologda -- I can’t remember what he was doing. But he died. In 1929 Daddy and I went to visit his widow, Aunt Emma. I can’t remember anything Jewish about her family.

I remember that in 1918, during the Civil War, the Balakhovich gang was active in Pskov. This leader of this group was as well known as Denikin; he used to hang the Reds. The war went on furiously. I was about three or four years old, and Mom and I and the nurse would hide under the window sill so as not to get hit by a stray bullet.

I can’t remember all the details, but I do remember that my nurse once took me out for a walk, and by chance we suddenly came into a square where corpses were hanging on gallows. I remember that we were very frightened. These were not pogroms, they did not touch Jews. It was basically the communists who were executed.

Mom and Dad always and without fail prayed before meals. They would wash their hands, wash them in a bowl, and then rinse them with water from a jug three times on each side. They pronounced the blessing for the meal: "Borukh ato adoinoi eloheinu…" After dinner the housemaid cleared the table and washed the dishes. I remember that Mom wouldn’t leave the kitchen -- she lost a part of her beauty in that kitchen! She did not trust the Russian housemaid – she was constantly afraid that she would break the rules of kashrut.

The housemaid was young, younger then mother. She was a good girl, but Mom wouldn’t let her enter the kitchen when she cooked; she only let her in there to wash the dishes. There were usually Russian housemaids in the house, but mother never let them cook lest they make something treif (not kosher) and violate the kosher requirements by mixing dairy products with meat and so on.

Once I started to cut butter with a knife for meat and spoiled the kosher knife. Mom snatched it away from me, and thrust it in a slot in the wooden floor. In such cases you have to stick the knife in the ground and keep it there for some time. In this way the object regains the property of being kosher, of being pure.

We had a Russian stove in the kitchen, in which Mom put meals prepared on Friday. On Saturday we did not warm up the food, because you were prohibited to make fire, but the Russian stove stayed warm all the following day until evening. Mum didn’t even turn on the electric light on Saturdays. You were not allowed to work, it was a complete Sabbath. But I don’t remember that we had a mezuzah on our doors.

We didn’t hire Jewish housemaids, only Russian ones. I remember that apart of them, a laundress came to the house, and even a seamstress. The laundress would wash our linen in our wash tub. Mom would tell me, "Rochole, take a tub and look how Darya washes, and wash your dolls’ dresses and your kerchiefs." The seamstress sewed all sorts of pants, shirts, underwear and linen for our family.

On Friday, in the first half of the day before the Sabbath began, Mom would go to the market. There she would buy a chicken, which I then took to the synagogue, to the old shoikhet, ] Gelikman, for hito slaughter it in accordance with all the rules. As I recall, he would pronounced a prayer holding the chicken above his head, making the sacrifice.

I would give him some money for that ceremony. He would give me back the chicken, and I would bring it home to Mom. She then plucked the chicken, singed it, and salted it – it was a very long procedure. Then she boiled or stewed it. Sometimes she prepared tsimes. Tsimes is a sweet tasting dish of carrots and prunes all stewed together with goose or duck fat. We always had compote and fruit on the table, too. Chicken soup was served on the table in a porcelain tureen. We lit two candles, and Mom baked challahkhalas. Everythingovered with a napkin. Mum would pray, and Dad would pray. I didn’t have to recite the prayers, I would simply sit and listen.

Mom always wore elegant clothes. She never put on a wig; she had brown hair and gray eyes. Daddy respected Mom very much. I remember that they rarely quarreled; the only time was when Daddy would come back home late on Fridays. For example, if father was expecting a customer to arrive from the village, but the customer was late and therefore Dad was late, too. Stars were already appearing in the sky, father should have been home already, and Mom would be terribly angry. She wouldn’t talk to father for a whole week, up to the following Sabbath.

There were very many Jews in Pskov before the war. In Yedinstva Street there was a synagogue, I remember it perfectly. It was wooden building on a hill, not so large, approximately for 100 persons. I went to the synagogue only on holidays. I remember what the rabbi looked like, and I remember his daughters; we were friends with his girls, but I can’t remember their names.

I have only very vague reminiscences of Rosh Hashanah, but I remember Yom Kippur better. On Yom Kippur, the Judgement Day, Daddy and Mom would fast; they wouldn’t eat anything for 24 hours. But I was given food. On that day I always went to the synagogue with Mom.

There was singing and praying and people cried. I remember a beautiful prayer Kol Nidrei. It was forbidden to carrying anything in your hands, and Mom even had to fasten her kerchief to her wrist in order not to hold it in her hand.

During Purim mother would bake the triangle cakes with poppy-seed and with raisins, we call them Hamantaschen, ] d she also made krebhen - small triangles of dough and meat. These were boiled in meat broth to make in a dish similar to pelmeny [pelmeny are a Russian variety of ravioli made of dough with minced meat inside.

You can boil them or you can fry them]. On Pesach at one time, matzah was baked in the synagogue, and Mom and my aunts would go there to help roll the dough. Before that we would all together make a thorough cleaning up of the house, so that there wouldn’t be a single crumb of bread anywhere. On this single occasion each year, that treasured buffet was then opened, and Passover utensils were taken out.

Everything was done very solemnly. Sometimes the family of Aunt Bertha, mother’s sister, would come for Passover. Mom made wine in a linen bag similar in its form to a cow’s udder. There was always stuffed fish on the table, with horseradish on a plate besides it.

Later, in the Russian school, we were taught atheism, against religion, that there was no God. Once, when I probably was in the 7th form, on one Passover evening I went to attend an anti-religious meeting instead of taking part in the seder at home. We had a Jewish theater, and we held meetings like this there. It was interesting. I had had a negative reaction to religious fanaticism from childhood. I felt that Mom was the biggest fanatic. But later, when I grew up, I changed my mind. I understood that I committed a crime against my mother.

Mom didn’t read anything in Russian. She only read religious books in the Jewish language. I didn’t read them myself, but I think it was Tanach. We had a few books in the house, if only those by Sholom Aleichem. Later, we had some books by Moliere.

I loved Mom, but I loved my father much more. He taught me to swim, to skate, to row! In summer we usually went to our summer residence, we rented it from some Russians each summer. It was on the Velikaya River.

Mom used to sing me this song:

“Iomim, Iomim, zingmir a libele?

Voz dei meidene vil, dei meidene vil,

A klendele von daf un shnaideren zoben

Nain, Mome, nain, du kensten nikht farshtein…"

" What does the girl want?

The girl wants a dress!

We need to go to the tailor.

No, Mama, no, you don’t understand me!

What does the girl want?

She wants beautiful boots!

We need to go to the shoemaker.

No, Mama, no, you don’t understand me!

What does the girl want?

She wants earrings!

We need to go to the jeweler.

No, Mama, no, you don’t understand me!

What does the girl want?

She wants a groom!

Yes, Mama, yes!

Now you understand what I want! “

She sang other songs too, but I can’ remember them anymore.

Let me tell you how I studied. The school was organized according to the “Dalton’s method.” I don’t remember now what it was all about, I only remember the name, and there was a special team method of teaching, by which one team studied one particular topic and the other another topic, and then they reported to each other. I left school in Pskov - after finishing 9 grades - almost illiterate, I didn’t know arithmetic, nothing!

Such teachers we had, that’s how they taught us! The history of the Communist Party - oh yes! – that we surely knew by heart! And none of my classmates anything, either, except for the history of the Communist Party! However, some of them managed to enter institutes right after school. I wasn't so lucky, and let me tell you why.

In 1931 I finished school and came from Pskov to Leningrad, in Tavricheskaya Street, to live with the family of Uncle Efim, mother’s brother. They lived in a communal (shared) apartment. I had to stay somewhere. The shared apartment was large, 5 rooms. All the neighbors were Russians, except for two Jewish families - the Zarkhins and Berkals. We lived very amicably.

All of us helped each other. Neither I, nor our neighbors the Zarkhins ever experienced anti-Semitism. The biggest room was occupied by Uncle Efim, his wife and two daughters - Anna and Raya. In the next room lived the Zarkhins with their son Solomon. Father rented a room for me from Russian neighbors.

When he was there, he asked Solomon Zarkhin: "You are a student, please, look after her, so that she behaves the right way". Solomon was 27 years old then, and I was 17. We fell in love with each other. He took me to the skating-rink, and once he exclaimed: "Why should I take care of her for someone else? Why don’t I make her my own wife? " I married him in 1932.

The wedding was a civil one, not Jewish. We had the usual party for friends. A friend of my husband was getting registered in the ZAGS [Civil Registry Office] that day too. My husband was an atheist. After were registered our marriage in the ZAGS, a group of friends and my Dad gathered for a party. Mum didn’t come, because there was no chupa.h[

My husband Solomon was categorically against having a religious ceremony, and Mom was terribly upset that her daughter’s wedding was not going to be celebrated in the religious way. So Mom didn’t come to my wedding in Leningrad at all!

My husband’s parents, Isaak Iosifovich Zarkhin and Lyubov Borisovna Zarkhin, were also religious people. In my husband’s family, when he was a boy, all the Jewish traditions and customs were observed. His mother was a housewife who brought up many children - 4 sons and 2 daughters. They came from the small town of Krasnye Strugi, not far from Pskov.

In Soviet times, my husband’s father, Isaak, was considered a lishenets3 , therefore my husband Solomon could not enter an institute of higher education after finishing grammar school. Only much later, when he was working as an ordinary machine operator and electrician, was he able to enter the Polytechnical Institute when the so-called “Workers’ call-up” was organized by the Bolsheviks. [“Workers’ call-up”– the draft of workers from factories to higher educational institutions.

One of the methods to create “people’s intellectuals” to substitute for the bourgeois specialists, invented by Bolsheviks]. From the fifth year of that institute he was taken into the Military Artillery Academy as an excellent student. They admitted 5 men, and all of them turned out to be Jewish.

When I got married I took the my husband’s surname - Zarkhin. I gave birth to my elder daughter Eugenia in 1933. Near my home in Leningrad they opened evening courses to train teachers for elementary school. On my student’s grant we were able to hire a Russian housemaid.

I completed the courses, compensating for the poor education I had received in grammar school. For one year I worked as a teacher at a Russian elementary school. There were no Jewish schools in Leningrad then! After I left my parents’ home 1931, I no longer observed Jewish traditions!

In 1934, when we already had a baby, I fell out with my husband because he was so jealous, and we even got divorced. I took back my maiden name Averbukh. But after that "divorce" we came home again together that very day, and never parted again for a single day, living together again; it was all like a game.

I was young, only 19, and that divorce didn’t scare me in the least. It is only now that divorces are serious, and back then – it was not so. Solomon was very jealous by nature. When we walked along the street I was supposed to look either at my feet, or at him. The slightest glance aside was the cause for jealousy. Even if someone would send me a letter congratulating me for something, he became jealous.

We officially registered our marriage for the second time only in 1947, when I was to be assigned a job after graduation from the Medical Institute. But I preferred to keep my maiden name Averbukh; I didn’t change it anymore. Two of my kids [Larisa and Gennady] were officially born outside wedlock.

When boys were born to my relatives’ families, they were circumcised on the eighth day. But they did not have a bar- mitzvah at 13, nor did I have a bat-mitzvah, because it was the Soviet regime.

My husband’s sister Frida Kotik suffered the arrest and execution of her husband, who was a Bolshevik who was shot in 1938 in Leningrad. She was left with a daughter, born in 1928, and a son, born in 1935. They were exiled to Rybinsk, and she died there soon after. The kids were sent to an orphanage.

- During the war

I entered the workers' faculty in the First Medical Institute, and then, in 1938,I was admitted without any problems to the institute itself. Studies began on September 1, and on September 29 I gave birth to my second daughter, Larisa! After that I took an academic leave for one year, and in 1941, when I was taking examinations for the second year, the war began.

I left for Malmysh in Kirov region to stay with my parents. They had already been evacuated from Pskov to Malmysh in the beginning of July, 1941. It happened like this: It was a Saturday, and they were standing in Yedinstva Street in Pskov, thinking about what they should do now, with the war having broken out, when an old Jew came by and addressed them in Yiddish, saying: "Iden, was steiten?!", which means:

"Jews, why are you standing here?! Do you think they are the Germans of 1918?? There - the Russians are running, and you must run away!!" And so they fled without anything, just small suitcases, and escaped on the first freight train. They found themselves in the Kirov region, in the town of Malmysh.

Solomon was at the front line near Leningrad, in Peterhof, as the commander of an artillery unit in the national irregular army. He went to the front as a volunteer, and I approved this choice. I told him: "If healthy Jews like you don’t go and fight, who will?!"

On September 31, 1941 a shell exploded right at his feet. People around got killed, but he miraculously remained alive. He didn’t lose his legs, but he could only walk on crutches. There was a wound 13 by 12 centimeters on his right hip.

He survived only because a medic gave him blood on the spot, and in the ambulance they gave him a direct transfusion of blood, otherwise he would have bled to death. Everything turned out fine, but he was very lucky. They began to treat him in Leningrad and then evacuated him to a hospital in Chita.

Many Jews stayed in Pskov during the war. All of them died. All of them were taken to the Vauliny hills in the suburbs of Pskov, forced to dig trenches and were buried in those same trenches alive. And then the Germans drove over those trenches in their tanks. Only one little girl named Galperina survived, she was sheltered by a Russian teacher in her cellar. I learned this from people whose relatives died there.

All 4 daughters and 2 sons of my grandparents Leibe and Hana Berkal were evacuated to the East of Russia during the war [1941-1945]. Grandfather was left alone with his neighbors [grandmother Hana had died much earlier]. They looked after him. But that family and my grandfather were all executed during the war. Grandfather was more than 70 years old then, and the Germans hung him. I learned this from Uncle Evsei, who at the front met a member of the family with which grandfather stayed.

Solomon was treated in a hospital in Chita and recovered. He then joined us, his evacuated family, in Malmysh, and worked as a mechanic at an alcohol producing plant there in the beginning of 1943. Our son Gennady was born in 1942.

In 1944 Solomon, as an invalid of war, received a call either from the military committee or from his factory to return to Leningrad. It was only possible to return there on the basis of such a summons, because the war was still going on. So we packed our things. We had no money for the trip. Solomon was given a large flask of spirit at his factory instead of money. He paid for everything with that spirit. Solomon also received winter felt boots from his military committee. But he could not put them on because of his wounded legs.

He sent me to sell them in the market. But I am not a skilful saleswoman, so one guy took one boot from me as if to look at it, and another seized the second boot, and they were gone. I had no time even to scream … Then Solomon was given a warrant for fire wood. Goods were exchanged for warrants then, free-of-charge, and the warrants were distributed by military committees. Solomon was an invalid of war of the second group and could obtain warrants for free. So we sold our warrant to someone else, and on that money we returned to Leningrad: I with three children, my husband and my parents. It was 1944, and the war was not over yet.

Post-war

On my return from evacuation, I enrolled in the Medical Institute and graduated from it in 1948. That year there was an oversupply of medical graduates, and all of us were queuing in the city department of public health to get an assignment for a job. I was temporarily employed for 2-3 months in Polyclinic 33 to substitute a surgeon on a leave.

Later, there was a vacancy for the post of regional doctor in Polyclinic 32 in the Petrogradsky district. I worked there for 26 years, eventually becoming head of the department.

My daughter Eugenia did not encounter any anti-Semitism at school. But when she finished school with a gold medal and wanted to enter the biology department of Leningrad State University in 1951, she found that article 5 was a problem. [article 5 was “nationality” in all Soviet questionnaires]. So she didn’t even attempt to enter that University, she was simply frightened. She knew the situation perfectly and went to study in the Forestry Academy instead, which it was not so difficult to enter. That’s how she became a forestry officer.

In 1953, when the well-known "Doctors’ plot" broke, I had an incident at work. A woman from a Russian family from my area of service came to the chief doctor of our polyclinic, and started to tell him that I was trying to poison her family with medicines.

By chance, this conversation was overheard by an ordinary Russian man, who was also my patient. He was outraged, and shouted: "I’ll tear your head off for Averbukh!". In 1953 two Jewish doctors in my district were fired. One of them died from a heart attack soon thereafter, and the other soon died from a stroke. That’s how upset they were. Our polyclinic was not touched by anti-Semitism because of our chief doctor. He didn’t dismissed any Jewish specialists. But I know that Jewish doctors were expelled from other polyclinics.

In my polyclinic I used to receive tickets to go to health resorts in the Pre-Baltic area, in Sochi. There I swam, lay in the sun, talked to people, went to the spa, made excursions. While I had a rest, my husband stayed at home with the children. He was also given tickets to sanatoriums, where he underwent medical treatment for his injured legs.

In 1963, I, as a doctor, received a three-room apartment in Sailor Zheleznyak Street. We still live there. Then my husband, as an invalid of war, received an apartment in the Rustaveli Street, so we have no problems with accommodation.

Father died in Leningrad in 1963, and Mom also died here in 1968, in the age of 85. Both of them are buried in the Jewish cemetery in Alexandrovskaya Farm. Dad underwent an operation for chronic inflammation and then died at home. He was buried the next day, not taken to morgue. I bought 10 meters of white fabric. The entire funeral ceremony was carried out by specialists.

We prayed in the synagogue at the cemetery. Each year after their death, kaddish was recited. I used to have kaddish recited annually, but I don’t do it any more. During the years following the war, in 1946-1950, mother didn’t observe the Jewish holidays, because there were serious problems with food supplies all over the country.

Later, in 1960s, she was too old and sick to regularly do so. However, on the rare occasions when she felt like cooking, she would prepare Jewish food. As she grew older, she spent more time sitting on the bench near her house in the company of her Russian neighbors.

As soon as my elder daughter Eugenia graduated from the Forestry Academy, she volunteered to work in the Far East; they were offering interesting work there, and she went there with her friends. She didn’t go for the money, but to work in an interesting position. We never attributed too much importance to money: interesting work, not money, was a priority. [You] don’t need both!!

At first she worked as a forest warden, then she left for Khabarovsk. Eugenia came back to Leningrad in 1964, defended her candidate’s thesis and became a senior scientific researcher. She worked until she died in 1988. She died of an incurable disease at a rather young age.

Gennady, my younger son, who was born in evacuation, also died very young of cancer in Leningrad in 1983. He had graduated from the Military Mechanical Institute and become a mechanical engineer. He had three children from three marriages. His younger son died of a congenital disease, and his elder children are in Israel now. They regularly sends us e-mail messages through the Intrenet -- my grandchildren have personal computers.

My daughter Eugenia (1933-1988) had one son, Alexei , who was born in 1964. He is a doctor and has a daughter, Elena, born in 1990. She is a schoolgirl, and they live in Krasnoyarsk. My daughter Larisa (born in 1938) has three children: twin boys Eugeny and Valery (born in 1961) and a daughter Olya (born in 1967), who is a medical nurse and lives in Germany with her two children:

Pavel (born in 1986) and Natasha (born in 1987). My grandson Eugeny lives in St. Petersburg; he is an engineer and has 3 children. My grandson Valery lives in Israel; he is also an engineer but doesn’t have any kids. He was already an engineer when hewent to Israel to study in the end of 1990s. He tried to enter the University in Jerusalem, but failed to pass the examinations. Still, he stayed there to live.

I am an internationalist. I was on friendly terms both with Tartars and Russians, and I never judged people by their national origin. I had friends of various nationalities both at school and in the institute. I sang in the academic chorus of veterans of war and labor in the Kalininsky district, where there were two Jews besides me. We sang only Russian songs. But my granddaughter told me about the Hesed on Shpalernaya Street and since then I come here often.

Now I, as my mother in her time, teach my daughter Larisa and my granddaughters to cook Jewish meals. It’s a custom with us to celebrate Jewish holidays at home, but we do not observe Sabbath. We do not attend to the synagogue, because we are not so religious.

In Hesed I receive monthly humanitarian aid, medical help if necessary, and I visit the Club in Hesed for lectures on Judaism. [after this interview in Hesed Rachel Meerovna hurried to one of such lectures]. I attend concerts of Jewish music at the philarmonic society. I have never been abroad, because we could never really afford it.