Pyotr Bograd

Moscow

Russia

Interviewer: Svetlana Bogdanova

Date of interview: July 2004

Pyotr Bograd is a tall, smart, slender, blue-eyed man.

One can tell he has a military bearing. He is very friendly, hospitable, and a remarkable story-teller.

He gets agitated, when talking about the war period or the death of his dear ones.

He lives in a spacious three- bedroom apartment in the northern part of Moscow.

His home is clean and cozy. He has a study where he writes his memoirs. He has many books on the history of war.

- Childhood memories

I was born in the Jewish colony [EKO] 1 of Dobroye on 9th August 1920. The colony was located in the south of Ukraine about 45 to 50 kilometers north of Nikolaev [420 km south of Kiev].

Our Jewish colony was formed in the early 19th century. [Editor's note: the interviewee must have confused the dates: the EKO was formed in 1891 and couldn't possibly have been involved in the formation of the Dobroye Jewish colony in the early 19th century, but this may have been so in the late 19th century and perhaps that was what Pyotr meant.]

The first residents, which comprised ten families, settled down there in 1802. I think they came from the vicinity of Vitebsk, Mogilyov, Poland and Lithuania, since the residents of our village spoke Yiddish with a Polish and Lithuanian accent.

The colonies appeared even before the Jewish Pale of Settlement 2 was established. [The town of Nikolaev was founded in 1789 and Jews settled there from its earliest days, engaging in commerce and crafts. Many of them moved there from Galicia, Poland. Later on, many Jewish families moved to the villages and estates in the vicinity of Nikolaev, mostly because of political reasons.]

There was sufficient resentment towards Jews among people and Jews requested the tsar to give them permission to settle down in the south and live their own way of life. [Editor's note: regarding the tsar's permit issued to Jews to settle down in the southern areas, this may have been a sort of a fable told in colonies in the early 19th century, since there are no existing documents or facts known to confirm this]. They were granted such permission and then the relocation began. Most of them settled down in Kherson province.

In spring 1801, eight Jewish colonies were established in this area containing 19 families amounting to about 1,000 people. Their material situation was quite miserable. They lived in poor stuffed huts, suffered from diseases and had no sufficient plain tools or medication.

The tsarist bureaucrats cheated the Jews and misappropriated a portion of the funds that the government allocated for the settlers until finally an honest and smart Russian investigation inspector arrived from Petersburg [St. Petersburg, Russia]. He discovered that the inspectors from the trustee agency transferred to Jews significantly lower quantities of wagons, ploughs, and harrows, than they had indicated in the report, and the oxen they had purchased for the settlers were too old and didn't work properly.

Gradually, after many years of starvation and suffering, the situation with the Jewish settlers began to improve. The instances of diseases and death rates began to decline; the settlers learned different crafts and raised their children, who were used to hard work. By the middle of the 19th century the colonies began to prosper. By this time, there were over 20 Jewish colonies in the south of Ukraine: Odessa and Kherson regions. They were mainly engaged in agriculture.

I remember our colony well. This was a big settlement occupying an area of over eight square kilometers. Its population was over 8,000 people. There was a seven-year Jewish school and two four-year schools: Jewish and German. There were a number of German colonists 3 in Dobroye living in one street. I don't know when they came to the village.

The street they lived in was called the Soviet Street [the street's former name is unknown]. They were rather wealthy and worked in a kolkhoz 4. Everything merged so tightly that it was hard to say who was or who wasn't a Jew. The German language almost merged with Yiddish.

There were four synagogues in Dobroye. The biggest synagogue for about 600-700 attendants was located across the street from our house. Artificial ponds sort of divided the village into three parts. They bred fish in those public ponds: sazan, carp and crucian fish.

The villagers were allowed to fish in the ponds. They also did farming and cattle breeding. Many were engaged in wine-growing. The vineyards were in the fields around the village where all villagers had plots of land [they worked in the kolkhoz, but also had their own plots of land where they could grow whatever they needed].

I remember how neatly they were arranged: there was a tent where farmers could take a rest hiding from the heat or from the rain to have a snack. There was one well for 10-15 plots. The water was worth the weight of gold in our area. There was always lack of potable water in the Black Sea vicinity.

Arele Speliarskiy, a short, unshaven man, was a janitor in the vineyards. He had a number of whistles of different tunes hanging on him. Nobody knew when he took a nap or a snack. He whistled at night and during the day, which meant that he was there on guard. The grape crops were always high.

When it was hot and you asked for a glass of water, they would offer you a copper mug of grape wine. The climate in our area was also favorable to grow grain crops. The mowing started in early March and the harvest ended in August. There was one threshing machine and one steamer in the colony. When the crops were particularly plentiful, the threshing was done sequentially in groups, or otherwise each family used primitive methods of threshing in their own yards.

At first, they used a special stone hauled by a pair of horses, and then they used a special board and a pair of horses. In the 1920s, the meeting of all colonists decided to build a grain storage facility to store dozens of thousands of grain. This was an impressive structure that one could see from the distance of many kilometers.

Most colonists were wealthy, but there were also poor families that needed support, which was given to them as needed. There were three butteries and a steam mill, a big milk farm producing high quality butter and cheese supplied to Odessa 5 and Nikolaev, in the colony.

In 1926, the village received a Joint 6 procured wheel tractor. All villagers rushed to gaze at it, when it arrived. It was a big event for the village and it was like a miracle. The electric power supplies started in 1938. Before its establishment, the houses were lit with kerosene lamps and candles. We bought a radio in 1933, when I finished the seventh grade.

- Family background

There was a Bograd clan in our village. My great-grandfather, Leib Bograd, was a blacksmith. There was also Mark Bograd, and I guess he was Leib's cousin brother. Mark had a daughter named Rosalia Bograd. She graduated from Medical College, I don't know where or when, and then she married Plekhanov 7 in Switzerland. She had a cousin brother named Yakov Bograd.

He graduated from a university in Switzerland and became a revolutionary [see Russian Revolution of 1917] 8, he was exiled to Siberia where he engaged himself in the establishment of the Soviet power in Siberia.

He was executed in 1919. I've read Rosalia Bograd's memoirs, which she wrote in Paris. Her family brought us her archives in the 1990s, when they visited us in Moscow. She was born in the Dobroye Jewish colony in 1856.

Rosalia lived with Plekhanov in Petersburg and lived there after he died. I don't know what she did for a living, but before the war she moved to Paris where her daughters lived. She died at the age of 93 in Paris in 1949.

My paternal grandfather, Yitzhak Bograd, was born in Dobroye in 1869. He and his brothers, Velvl and Aizik Bograd, finished cheder and became blacksmiths. My grandmother, Zipora Bograd, was born in 1875, and she worked in the fields all her life.

My grandfather and Aizik worked in one forge, and Velvl worked in the Jewish colony in a neighboring village. My grandfather horseshoed horses, and fixed iron wires on wagons, caravans and carts. My grandfather's sister, Minka, and her husband, Boruch Reznik, lived near the synagogue, which was converted into a club in 1931, during the collectivization [in the USSR] 9 and struggle against religion 10. They were my favorites. Boruch made wooden wheels and spokes.

My grandfather also had a sister called Genia. She got married young and left the colony. This is all I know about her. My grandfather's brother, Leib Bograd, moved to the USA before the revolution of 1917. He died there. He had five children. I only know about his daughter, Leya, born in the USA in 1920.

We met in the 1990s. Though I knew about her before, we couldn't communicate since this wasn't allowed in the former USSR [it was dangerous to keep in touch with relatives abroad] 11 and was punishable. We met, when I visited the USA, and she visited me in Moscow.

I remember my grandfather's big and beautiful shell rock house and the synagogue across the street. His family was wealthy. There was a forge near the house. I can also remember a picture of my grandfather, Yitzhak, wearing a linen shirt with coal burnt spots on it, fixing a horseshoe. There was his forge with the flames in the furnace behind him and flashes of flames on his plain tools, iron pieces and iron sheets. He could read and write [the majority of the rural population of this time was illiterate], and was a very kind and warm person. He worked hard all his life. I think my grandfather had his position in the community.

In 1904, my uncle Iosif, my father's older brother, was recruited to the army, and a sergeant major said to my uncle, 'Look at you, zhidovskaya mug!' ['zhidovskaya' means 'Jewish' pejoratively in Ukrainian]. My uncle was a very short-tempered and brusque man. He drew back his arm and hit the sergeant major so hard that he knocked out his teeth. He was sentenced to six years in prison in Nikolaev. My grandfather went to Nikolaev and brought Iosif back home. He must have had contacts and influence, I guess.

My great-grandfather, Lev Bograd, wasn't a poor man. He left my grandfather a forge. My grandmother, grandfather, my father and our family lived in the house. My grandfather gave one small room and an ante-room to my father's family in his house.

There was a big kitchen and an annex where two of my uncles and their families lived. There was a stable and a cow shed in the yard. There were also pantries where the family stored cattle food, a food cellar behind the forge, and a basement with a wine storage.

There were few wells in the village. The water was filtered, but it still had a salty taste. We collected rain water in a basin in the yard. There was about a ten-meter deep well with very salty water in the yard. My grandfather needed this well to provide water to the horses that he shoed.

My grandfather had two to three horses and two to three cows that my grandmother took care of. My grandmother was a housewife, which was common with Jewish women. There was a big table for 12-15 people in the dining room. We always had poor people visiting us on holidays and my grandmother gave them food to take home.

She was a very kind person. Her daughters-in-law, my mother and Aunt Sonia helped her in the house. My grandmother didn't cover her head at home. She had black hair which she wore in a long plait. She wore plain clothes. She usually had her housecoat on.

My grandfather and his brothers wore coats with their collars lined with beaver's fur. My grandfather wore a yarmulka at meals and to the synagogue, and a cap at work. My grandparents were religious. My grandmother observed all traditions strictly. She made sure everyone followed the traditions. My grandfather, being a laborer, might have breached the rules, when my grandmother wasn't watching. I remember seeing him smoking rather odorous tobacco.

It was Saturday, and he waved his hand to me to stay silent, and enjoyed the smoke-break. He told me not to mention this to my grandmother. [Smoking is forbidden on Sabbath by most of the interpretations of halakhah.] My grandfather closed his forge on Friday evening. My grandmother cooked for the holiday.

I have bright memories about Pesach. My grandfather heated a huge iron bowl to bake casseroles. All plates, pots, knives and forks were washed in a big basin in the yard. The house was whitewashed and painted. Everything was to be clean. My grandmother was very tidy. She had separate crockery for Pesach.

Each corner in the house was swept to remove any bit of crumbs. Grandmother made matzah. A wealthy Jew who lived across the street from us had a bakery and a special unit for making matzah. When collectivization began, this poor baker was persecuted, and from then on my grandmother made matzah at home.

A few housewives got together in my grandmother's kitchen on the eve of Pesach, they rolled the dough as much as the length of the table allowed. We, kids, made holes in it with forks. The dough was then rolled on sticks and baked in the Russian stove 12. All children and grandchildren, my uncles from Kiev and from Kharkov [420 km west of Kiev], about 20 of us, got together at Pesach.

This was a big, common, working family. My grandfather hid away a piece of matzah and the youngest in the family, which was me, was to find it. My grandparents went to the synagogue.

My grandfather went to the synagogue at dawn before and after work. My grandmother always went to the synagogue on holidays. She covered her head with a black lace shawl and she and I went to the upper tier. She pointed out to me my grandfather who sat on the ground tier.

When I went to cheder, I started going to the synagogue with my grandfather. He used to sit in the first row and I sat beside him. There was a mezuzah on the door of each house. On Sabbath and holidays we lit candles. I remember the hard times, when there were no candles available, my grandmother removed the inside of a potato, poured some oil inside and installed a piece of cotton wool.

My grandparents perished in 1941, when the Germans executed all villagers.

My grandparents had eleven children: Two of them died in infancy. Six boys and three girls survived. All I know about them is what my father told me, but I wasn't interested at the time and I didn't go into details about my relatives. Only my father's older brother, Iosif, followed into my grandfather's footsteps and became a blacksmith. My father became a butter and cheese maker, and my uncle, Yefim, graduated from a higher Party School 13. He joined the Communist Party in 1917 and was rector of Kiev University.

Uncle Boris was engaged in the state trade. He was an expert in fabric. My father's older sister, Dina, married Victor Kogan, a Jew and a very nice person. He dealt in agriculture in the neighboring village that was also a Jewish colony. He died from tuberculosis in 1930. While working in the field he drank some cold water. Tuberculosis was incurable in those days. Uncle Yefim helped Dina to get a job at the radio plant in Kharkov. Later, she became a party organization supervisor in a shop of the plant.

Uncle Abram served in the army. He moved to the town of Slaviansk [about 500 km south-west of Kiev], where he went to work at a plant and was promoted to deputy director. Uncle Nisan Bograd dealt in agriculture. He got married in 1928 and died in 1929. His son was born shortly after he died.

He was named Nisan after his father. He lived somewhere in Ukraine, but we didn't have contact with him. Uncle Nisan had a prearranged marriage. At first, there was a negotiation meeting and then there came a matchmaker [shadkhan]. My uncle Nisan's fiancee came from the neighboring village. I attended all important family events. I was about eight years old. I was a cute child with long black curly hair. My uncle and I went to make an acquaintance with his fiancee.

The girl was a real beauty. Her name was Katia. My grandfather's brother lived in the same village. We spent the night at his house. Katia gave her consent to visit our family and meet my grandparents. Everybody liked her: she was so beautiful. But then what happened was that Katia all of a sudden fell in love with my uncle's cousin brother, Benia, who lived next to our house.

Benia also liked Katia a lot, but he had a fiancee, so everything went wrong. My uncle was very upset. I even think this unfortunate incident affected his health and he died young. He married Hasia Tsypliarskaya. She came from a wealthy family who lived in our colony. I remember the chuppah and my uncle Nisan under it. He was given a sip of vodka according to tradition. We went around throwing confetti on the bride and bridegroom.

Aunt Liya Bograd was single. She studied the profession of Indian- rubber expertise at a technical school. Later, she graduated from the Moscow Agricultural Academy in the early 1940s and after that she worked in the scientific field at the India-rubber testing facility in Kursk, Russia.

Aunt Revekka Sadikova [nee Bograd], graduated from a Teachers' Training College in Nikolaev in the 1930s and worked as a teacher at a secondary school. She was married to Abram Sadikov from Nikolaev. He perished at the front in 1942. Their son Yakov was born in 1934. Aunt Riva [Revekka] and he evacuated to the Ural during the Great Patriotic War 14 and lived there. I had no contact with them.

My father, Lev Bograd whose Jewish name was Leib, was born in 1896. He graduated from a four-year Jewish elementary school. He could read and write well in Russian. He worked as a cattle drover for cattle dealers and later he finished a course in cheese making and became one of the best cheese makers in the region. He had his own business in our village. Later, he moved to Nikolaev where he worked at the cheese factory where he was employed as a shop superintendent. My father was a kind person. He took after his father.

My mother, Sonia [short for Sophia], was born in 1897. Her maiden name was Naydina. I was named after her father, Peisach Naydin, whom I didn't know as he had died before I was born. He was a grain quality assurance expert. He came to our colony from Smela. My mother was born in Smela [Cherkasy region, Ukraine, about 170 km from Kiev].

Her older sister, Tsylia, was born in 1892. My mother also had two brothers. One was called Alter, though he had a second name of Isaac. It's customary with Jews to give their children two names. He was a successful trader during the NEP 15 and lived in Bryansk, Russia. When the NEP was abandoned in the early 1920s, somebody set his store on fire. He and his family managed to escape. They moved in with us and lived in our house. Later he went to work in the trade section of the kolkhoz.

My mother's younger brother, Shula, was a loader. He was my favorite uncle. He also worked in the kolkhoz. He often stayed with us. His only asset was a hornless cow. Only he was allowed to milk it. Before the milking my uncle tied her legs. I don't know why he had bought the cow or why he needed it, but we all knew that it was Uncle Shula's cow and we could always have its milk.

Later he married aunt Tsylia's husband's sister. She was an accountant and they lived a happy life. My uncle and his younger daughter died during the epidemic of typhus and hunger in evacuation during the Great Patriotic War. His son lives in Israel now.

My mother had a very strict morale. She raised my brother and me to observe her strict rules. Boys used to play around without wearing pants in the village, but my mother never allowed us to go out like that. We always wore clean white shirts. When she washed us, she rubbed us so that we screamed, 'Oh, my God!' She was very tidy. On the day of her death she got up, took a shower, and died. This happened in 1981.

My mother graduated from a four-year Jewish elementary school, and could read and write in Yiddish and Russian. My mother was a dressmaker, when she was young. Families commonly invited a dressmaker to their house where she stayed and had meals with them and meanwhile made clothes for all members of the family.

The majority of her clients were the German families. Her grandfather, Ruve, was a wealthy man. I don't know whether he was her paternal or maternal grandfather, but he raised her, educated her and taught her to work and earn money. My parents got married in 1919. I don't know any details of their acquaintance, but they met each other without matchmakers.

They had a chuppah, klezmer musicians and a huge wedding party which half of the village attended.

- Growing up

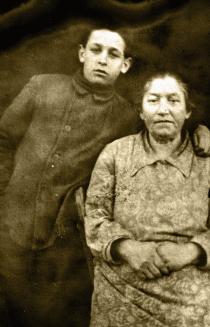

My parents had two sons. I was born in 1920, and then my brother, Ruvim Bograd. My brother was short and had blonde curly hair. My mother was also a blonde. I remember the day when he was born.

This happened on 21st January 1924. My mother was lying in her bed tied to the legs of the bed. My mother's younger brother wrapped me in a shawl and took me away. Then I remember my younger brother lying in his bed playing with the golden ring on a thread that my grandmother was holding.

He grew up and went to school. He studied well. He transferred to the fifth grade after finishing the third grade. He was a clever child. Ruvim went to school in 1931. He didn't go to cheder. In 1938, he finished the seventh grade and entered the Jewish Machine Building Technical School in Odessa. I took him to Odessa and rented a room for him. In 1942, Ruvim was mobilized to the army. He perished near Stalingrad.

My grandmother insisted that I go to cheder in 1926. I didn't feel like taking any learning responsibilities, but grandma said, 'No, it's going to be the cheder and that's that.' I went to cheder with our neighbor's boys. Our teacher was Iosif Lamdn. I learned to read and write in Yiddish at the cheder. I can still remember reading the letters, alef, beit, gimel and then a candy falling onto my desk.

The rabbi was standing by my desk. He said, 'This is what God has sent you.' I thanked the rabbi and thought how God could have sent me the candy. I looked up but there was no hole or slit in the ceiling. Then I looked at what God was going to send Borka Minkov and noticed that the rabbi dropped a candy onto his desk from his palm. I said, 'Rabbi, but you've dropped this!', and he replied, 'You, mamzer!' and hit me on my hands with his ruler. Mamzer means 'bastard', it's a curse word [Hebrew]. However strange it is I've stopped believing in God since then. Then I went to the seven-year Jewish school where all the subjects were taught in Yiddish.

In the early 1920s, our young people organized the agricultural commune 'Novy byt' ['New way of life', Ukrainian], actually it was a prototype of the kibbutz in Israel, but unfortunately, there was a direction to establish kolkhozes. Two kolkhozes were formed. One was formed on the basis of the agricultural commune, 'Novy byt', and the second one was 'Vperyod' ['Forward', Ukrainian]. In the middle of the 1930s the third kolkhoz was formed.

It was named 'Krasny Luch' ['red ray', Ukrainian]. The famine [in Ukraine] 16 in the 1930s affected these kolkhozes very badly, but the kolkhoz management had stored some corn before, which supported the kolkhoz members during this period of time, and there were no starved people in our village.

There was a special agricultural farm established five kilometers from the colony for the children of the kolkhoz members to receive a secondary agricultural education. I had a wonderful childhood and enjoyed doing any work. I worked in the field, in the vineyard, on the threshing floor, harvesting corns and sunflowers.

In 1936, after completing school, I entered the Poltava Railroad Technical College [Ukraine]. It trained railroad employees, locomotive operators and engineers. Of course, it was difficult for me to study in this technical school after just finishing the seven-year school in the village.

I had to fill up the gaps in my education, but I still had excellent marks. I lived a merry and careless student's life and took part in public activities. I joined the Komsomol 17, and became a member of the Komsomol committee [Komsomol units existed at all educational and industrial enterprises. They were headed by Komsomol committees involved in organizational activities]. I was full of energy when I was young.

In spring I was given the task to inspect the track between the Romodan and Kremenchug stations [about 1000 km south of Moscow]. There was another student and two trackmen who covered this road inspecting the track, beams, plates, bolts, spikes and switches. We walked 200 kilometers and a daily Poltava newspaper published reports of our work.

We detected a number of problem areas and the railroad track maintenance superintendent issued an order of appreciation for our work. This was a serious assessment. When we returned to the school after a short vacation I was invited to a meeting of the Komsomol committee. When I saw my comrades, I felt uncomfortable at once. My close friends were looking at me with condemnation and even defiance, as if I was a stranger.

The secretary of the Komsomol committee was sitting at the head of the table. He and I studied and took part in public activities together. The Party secretary was sitting beside him, and my co-villager, Grishka Kosoy. I was asked, 'Bograd, where is your uncle?' I replied, 'Which one? I have a few.' I was told, 'Your uncle from Kiev who is rector of Kiev State Agricultural College.'

There was a pause and then there came a question, as if an explosion over my head: 'Do you know that he is an enemy of the people 18?' I replied from my heart rather than upon consideration, 'This cannot be!' Then it all started.

This was the period of arrests [during the Great Terror] 19, of course, we believed everything that the newspapers published, but this hadn't affected our family before. My schoolfellows continued to torment and interrogate me: 'Aha, this cannot be! He is the same! He's been in prison for three months, but you haven't mentioned it. You are silent and pretend you take an active part in work! You, double-dealer, the son of wealthy parents, you've got into this leadership unit and you are hiding away your criminal soul!'

My uncle Yefim Bograd, who was declared an enemy of the people so suddenly, was a communist since 1917 and made it a long way in the party hierarchy. It was impossible to believe this! In the early 1930s he was a secretary of the Kobeliaki district party committee of Kharkov region, and then he became rector of the Communist College named after Kossior 20 in Kiev. In March 1937, my uncle was elected secretary of the Communist Party committee of the Bolsheviks 21 of the College.

At dawn of the following day he was arrested. After many interrogations and other hardships my uncle was sent to the vicinity of Magadan [Russia] where he perished in 1945.

My friend, Grishka Kosoy, was the only one who kept quiet at the Komsomol committee meeting. He had known about the arrest of Yefim Bograd for quite a while before the meeting. He must have believed that I also knew about it since the other villagers and my relatives from Dobroye also knew about it, but told me nothing as they felt sorry for me.

Other Komsomol members continued condemning me, 'Everything that you've done at this school has been your special tactic. You've acted under your uncle's command, and he is an enemy of the people. He's instructed you and taught you to do sabotage on the railroad'. They also reminded me about the time when I received those so-called 'instructions.'

In 1936, I visited my uncle in Kiev, when I was on my way to school after having practical training on sites. I believed Grishka Kosoy was my friend since childhood, but he reported that my uncle was an enemy of the people. He submitted a reporting note to the Komsomol committee. It was his report that 'started' the machine. I was expelled from the Komsomol, and that evening I was actually dragged to the meeting of the Poltava town Komsomol committee where they knew me well. It was a sensation of the town committee meeting: Bograd - a double dealer; an activist and a henchman of an enemy of the people!

They made me tell my life story, a detailed resume. I told them that my father was a servant before the revolution working for a cattle dealer. They replied, 'No, you are the son of a cattle dealer! That's why you have this ideology!' Anything I said was interpreted vice versa. I was spellbound. A storm of accusations hit me repeating the popular current newspaper headlines! The verdict was unanimous: 'approve expulsion from the Komsomol.'

On the following day, I resigned from the Komsomol committee and left for the practical training at the Poltava track maintenance service. On the outside nothing seemed to have changed. No, something had changed: my former friends avoided me and there was an empty space around me.

Besides, when I was resigning, the Komsomol committee discovered a shortage of 50 rubles, which happened quite 'on time.' The secretary of the Komsomol committee was guilty, but the incident gave grounds for my conviction. Fortunately, the investigation process found no guilt in my conduct. I expected an arrest every instant.

On 1st September I went to school at seven o'clock in the morning, when I saw the notice issued by the director of the school on the information board: 'Expel student Bograd from school for his relations with an enemy of the people'. I stood still. I thought, 'What am I to do? Where do I go? What's awaiting me in the future? No, that's all. My life is over!' I was standing there.

My co-students were passing by without even looking at me. That was it! The evil fate had captured its victim. But no, it turned out there were real men in this atmosphere of overall fear. All of a sudden I heard a familiar hoarse voice whispering, 'Go to the personnel training department in Kharkov immediately. You'll take decisions there'. [Editor's note: this man wanted to help Pyotr by giving him good advice regarding leaving those people who treated him so unfairly. He advised him to move to a bigger town where nobody knew him and where he might expect to find fair attitude.] This was Pyotr Kihtenko, chief of the study department of my technical school, our favorite teacher!

I was homeless and jobless for the next two days; I didn't sleep or eat. In the afternoon, I tried to make an appointment with the director of the school or managers of the Poltava railroad, but I failed. The railway station was closed at night and it was cold in the park. I lied down on a bench and then had to run around to get warm, when all of a sudden I bumped into the janitor of our school, an old railroad man and a communist.

He offered to rescue me and took me to his home, and gave me food. I slept at his home and went to Kharkov in the morning. When I arrived, I went to the Railroad department. I didn't get an appointment at the personnel department, but they told me to write a report and take it the next day.

My father's older sister, Dina Kogan, worked at the radio plant in Kharkov. I stayed with her. She wasn't affected by the tragedy of her brother Yefim. I told her my story and she helped me write a letter to the chief of the personnel training department. The chief was very polite to me. We had a face-to-face discussion, and though my uncle's name wasn't mentioned, I understood that he knew him well and didn't believe he was guilty. At the end of our meeting he told me to go back to my parents and wait there. He said, 'You cannot stay in Kharkov or Poltava.' In the evening, Aunt Dina said he was arrested on that very same day. He happened to have known my uncle from the party activities.

At about four o'clock in the morning, we woke up from the sound of someone knocking on the front door. Somebody opened the door, then it was quiet, knocking on the door of our neighbor, quiet again. Aunt Dina went to the kitchen. She returned and said that there was a search at her neighbor's house and so I had to get dressed quickly and get out of the building. I managed to escape unnoticed.

I went past a black car that people called 'Black raven' [this derived from 'Varon', 'raven' in Russian, bringing trouble], and went away quickly without looking back. In the evening I asked the conductor to allow me to board the train 'Kharkov-Odessa'.

Once at my parents' house my despair and worry burst out of me in tears. At first, I couldn't even explain what had happened. However, the young thirst for life took over and I hid the memory of what had happened deep inside and started looking for something else. I avoided any conversations about the past or reasons of my resignation from school.

My father was a foreman at the buttery and I went to work there as an accounting clerk. It was a dull and boring job.

All of a sudden the director of the plant offered me the position of a secretary and cashier at the plant. The memory of my recent past and the fear that it might come back gave no way for me to enjoy life and work to the utmost. Since my childhood I'd been taught to tell the truth, and this forced silence or lies caused such pains of conscience that I felt undermined and defective.

Then January 1938 came. Stalin's words, 'A son is not responsible for his father', echoed all over the country. [Editor's note: the strategy, which one might call 'two steps forward, one step back,' allowed Stalin to put the blame for the 'excesses' on low-ranking officials and to portray himself as a savior after the completion of large-scale systematic deportations of entire families.] It meant that a father could be bad or good, but the ideal of a son was Pavlik Morozov 22; and family relations were taken up by the priority ties 'an individual- a state.' However, I focused on the formula and in late January I wrote Stalin a letter with the description of what had happened to me.

Time passed, but there was no response and I was losing hope to ever get any, when all of a sudden I received a letter from Stalin's reception! 'The Poltava regional party committee is authorized to review your case.' In early August, I was invited to a sitting of the bureau of the regional party committee. On the evening after the meeting, I was already at the hostel of the technical school that had recently ousted me and got my Komsomol membership card returned to me. One year of my student's life was lost, and my co-students had already graduated, but I felt like having my wings back. I was consoled by having a letter from the reception of Stalin!

However, on 1st September, the director of the school refused to give me permission to attend classes or talk to me. And again I got salutary advice, a school teacher advised me to address the People's Commissar of Transportation Lines called Kaganovich 23 directly. I sent him a telegram where I informed him on the cancellation of the false conviction in cooperation with the 'enemy of the people,' resumption of my Komsomol membership and non-responsiveness of the director of the school. My family was terribly worried for a few days.

We didn't know what was going to happen and what we were to do, until I got a telegram from Poltava, 'Arrive urgently. Your school admission has been restored.' So it seemed everything was going to be fine. The Soviet society continued to be filled with suspicions and prejudices. Some students watched me openly and never missed a chance to humiliate me and remind me of what had happened before. Nobody showed any sign of sympathy, but I managed to graduate from my school successfully.

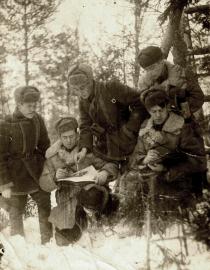

In August 1939, after graduating from the Poltava Railroad Technical School, I worked as a foreman of a mobile excavator column on the construction of the Magnitogorsk-Karaganda [1,400-2,400 km east of Moscow] railroad. I requested employment on railroad construction sites involving the use of new equipment i.e. excavators, trailer graders, dump trucks, tracklayers, etc. I was responsible for the operation of a 1.5 square-meter excavator with an electric engine. We lived in field tents, had a field kitchen trailer and made benches and tables on our accommodation sites. There was also a tent store. We wore what we had. Tarpaulin boots with rubber soles were common at that time. When the weather was nasty, we used sacks and the key personnel had tarpaulin coats with hoods.

One month later I went to serve in the army. Since October 1939 I served in a railroad unit in the Far East near Murmansk [about 2,000 km from Moscow]. Later, I relocated to an infantry school of the Ural Military Regiment. At the age of 20 I was a cadet and a company first sergeant. My squad of cadets took part in a contest where we were to march 25 kilometers, cross a water obstacle using whatever we could find at hand, shoot a target, hand-to-hand fight and clear obstacles without smoke or other breaks.

It was a challenge to the will and endurance, and readiness to help your comrade especially with the heat, mosquitoes and midges, pungent sweat and our shirts sticking to the hot skin. I brought up the rear and was also carrying our junior sergeant's rifle besides my ammunition. He had quit the game. All of a sudden a horse rider knocked me; I fell and accidentally cut my right arm with the bayonet. It was a shock, sudden pain, and this caused confusion in the squad. The squad commanding officer yelled the order, 'First sergeant! Stand up! Help yourself! Get going!' It never occurred to me to do otherwise.

Overcoming the pain I kept running. We swam across the river, cleared up the obstacles, won the bayonet fight on elastic bayonets. I won a sufficient number of points. The squad became a winner, and for me it was a victory over myself, a test of my self-control and will. This was how the military character was developed in the Soviet army. This was the way of moral and physical training of Soviet officers for the forthcoming war. The professional forces managed to delay German troops on the first days of the war, but they closed the road for the Germans with their own bodies.

On the following day after the competition I turned twenty. I was arranging a full profile trench and finished the work before dawn. My hand hurt of course, but I was extremely proud that my spirit was stronger than my flesh. Everything looked beautiful: the youth, everything was possible and it was impossible to believe that we were on the threshold of a horrific war.

- During the war

The war happened to be a turning point in the life of my colony. All men fit for military service went to the front at the beginning of the war. Some villagers moved to the east of Ukraine, but many others stayed in the village. My grandparents tried to leave the colony on a wagon later, but the Germans captured them and they were forced to move back.

Fascist troops invaded the village without a single shot in late August 1941. On 2nd September they shot old people, children and ill people, 257 in total. My grandparents, Aunt Haya, Sura, Iosif's wife, Uncle Velvl, and my 15-year-old cousin sister Basia, all perished. They were killed in the German cemetery near a ravine.

My grandmother couldn't walk and was taken there on a wagon. Basia managed to escape and hide in a haystack, but the German soldiers found and killed her. What makes me particularly angry is that the shooting was done by local German residents. I only got to know that my dear ones had perished after the war, though I knew that the Germans were killing Jews during the war. My parents lived in Nikolaev before the war. My father was a production engineer at the buttery.

When the war began, I sent my parents a telegram from Pskov [Russia] telling them that I would soon go to the front and sent them my certificate. They received allowances by this certificate through the wartime. In early August German troops approached Nikolaev. My father and mother crossed the Dnieper and took a train to Saratov [Russia], where my mother's brother and his family lived. My uncle was soon recruited to the army. Later my parents moved to the village of Orlovka in Saratov region where my father worked at the elevator.

In 1970 I visited my home colony. It wasn't our colony any longer. Everything that had been created was destroyed and the vineyards were removed. There was only the school, overgrown ponds and a poor monument on the common grave left in the village. When I saw the church on the site of the former synagogue, I felt sick. After the war Western Ukrainians moved into the village. Everything built with such care before was in ruins. I don't feel like going there again.

I took part in the Great Patriotic War from the very beginning. I was in the town of Plunge [Lithuania] on the Lithuanian-German border where I was relocated to continue my mandatory service. I arrived there in the late evening of 21st June 1941. I was head of the group of graduate lieutenants of the Kamyshlov infantry school assigned to the 204th mount rifle regiment. A dismal artillery barrage occurred at dawn on 22nd June. Nobody but the duty officer was aware of our arrival at the regiment. We didn't have weapons or understanding of the actual situation on the border.

The regiment started combat action while we didn't know what we were to do. In the afternoon we 'bumped into' a battalion commander of the 204th regiment and he assigned us to his battalion as unarmed privates. The sudden attack created an overall mess on the border and each officer or soldier was acting at his own discretion and understanding. There were no clear orders or knowledge of the situation. When we were retreating, planes with black crosses on them were constantly hanging over our heads.

I saw our first little plane near Riga [Latvia]. We were retreating, when we saw a plane and started shooting at it thinking it was a German plane. It started waving its wings: 'It's ours, ours!' This must have been a communication plane. We left with a commander of an armored train on 23rd June, when the situation became a bit clearer.

The motorcycle rode along forest roads looking for the chief of the army staff. We avoided highways due to continuous air force attacks where the German planes ruled in the skies completely. Some 40-50 kilometers west of the town of Siauliai, we bumped into a group of communications military under the command of a captain. They were installing cable. Such was the start of my service in the army during the Great Patriotic War.

At first I fought on the Western border, Plunge, and then our corps was divided into two parts: one part headed to Tallinn [Estonia], and the other one, including me, headed to Pskov [Russia, about 600 km west of Moscow]. A regiment was formed from the remaining western units. I was a company commanding officer. I was wounded and taken to a hospital in Leningrad and relocated to Vologda. From Vologda I was supposed to return to Leningrad, but the city was already cut off [see Blockade of Leningrad] 24. I was sent to Moscow for the shooting training course 'Vystrel' ['shot' in Russian].

On 16th October 1941, when panic started in Moscow, Stalin ordered the formation of an officer battalion and sent it to Klin [about 75 km from Moscow]. [Editor's note: The German Moscow offensive called Operation Taifun started on 2nd October 1941.] There were minor collisions. Later I was ordered to move to Tihvin where I took part in combat action. Then I moved to Lodeynoye Field [about 600 km north of Moscow].

I was a battalion commanding officer there. We took our defense, and then I fought south of Lake Ladoga. When the 'Road of Life' 25 was constructed, we patrolled it on skis. Then we relocated to the Transpolar area [Zapoliariye]. We fought near Kandalaksha [1,400 km north of Moscow], took part in the defeat of a German grouping in this area.

Then we were assigned to the second Ukrainian Front near Bucharest [Romania]. Then we relocated to the vicinity of Budapest [Hungary] to the third Ukrainian Front. Then we were near Pecs [South- Western Hungary, near to the then Yugoslav border], when Germans struck a blow there. At the end of the war I was on the border of Austria and [former] Yugoslavia in the direction of Zagreb [today Croatia].

The hardest combat actions were between 1941 and 1942. When we were retreating, I can't remember what we ate or where we slept. We were depressed. This was the hardest period. When the war began, I felt like being a baby again, when my mother would hold and comfort me. Later I got used to blood, to the deceased and the wounded, to non-stop bombings, to the edge of death. I wasn't running away, but it was dark in my heart. It's hard to find words to describe what I felt.

It was the first month of the war. After the defeat near Riga, the major portion of the tenth rifle corps was retreating to Tallinn, and the defeated units were gathering in the vicinity of Pskov. On the night of 1st July, the 202nd mount infantry regiment was formed near Pskov. I was appointed commanding officer of the fourth mount infantry company. By 6th July the company took defense in the north of the village of Dymovo [Russia].

The front line was on the former border between the USSR and Latvia [see Occupation of the Baltic Republics] 26. In the morning of 6th July, I went to check on the guards about 800 meters from the front line near some abandoned buildings in a coppice. I was accompanied by a young private. We found no guards there. I started moving around hoping to find my subordinates, when the Germans discovered me.

They yelled in Russian and German: 'Russ', surrender!' I pretended I didn't understand Russian or German and crawled back to my company positions. They started shooting and I ordered my accompanying private to shoot back. I raised my right hand with a gun, when a bullet hit me. I took my gun with my left hand and started shooting back. We managed to get to the coppice where we were encircled. I thought 'that's it, it's my last day.'

Our political officer 27 hearing the shooting sent a rifle squad to help us. I was rescued from being captured. I had my hand bandaged and went to the medical company of the regiment. Later we found out that the Germans had captured our guards when they were asleep. Of course, this was my negligence, but it could be explained. The company was formed in a hurry from the retreating soldiers and sergeants and I didn't have time to know more about them. I took a course of training of commanding officers of machine gun companies and took part in combat actions near Moscow with other cadets of the course.

In January 1942, I was an assistant commanding officer of the first battalion of the 94th infantry regiment. After hard combat actions on the Swir' River near the Lodeynoye Field the battalion took defense in the north of the Yandeba River. There was no continuous front line, and there were mine fields separating the defense areas. I had an extremely heavy Finnish machine gun. It was a trophy gun - the Finns allied with the Germans at that time.

The commanding officer of the battalion ordered me to go to the left flank company. I was to walk about 800 meters. There was a path in the deep snow and I had my camouflage robe on. After about 500 meters I heard somebody speaking Finnish. I saw four Finns moving in our direction on skis. When they had approached to about 30 meters I decided to shoot.

When I pulled the trigger, there came only the sound of a click. The Finns heard the sound and turned back rushing to escape. I don't know whether this Finnish gun rescued me or not but I had to throw it away. However, I never walked alone again and always had a hand gun besides a submachine gun with me. I kept it in my bosom since its lubricant froze and it was impossible to shoot it.

After the snowy and frosty winter the commander of the seventh army gave an order to prepare an offensive. Winter 1942 was frosty and hard. All roads were covered with snow and there were minimum supplies delivered to the army. Soldiers had to carry bread, pea soup packages and cooked millet from the army storages for about ten kilometers from the front line.

We cut frozen bread with our digging tools and heated it over the fire. We ate killed horses. We lacked food and weapons. We had to save. However, we had sufficient clothing. We had valenki [warm Russian felt boots], cotton wool trousers and jackets. I didn't wear my padded jacket since we had two pairs of warm underwear. In summer we wore boots.

We had field caps with red stars on our heads. There was also a warm head liner. I wore my jacket till July as summers are also cool in this area. At times we were given vodka. Each battalion had a barrel. Each of us was given 100 grams. Many of my fellow comrades grew very thin during the winter. There were many suffering from dystrophy.

There was deep snow and even during the combat action we had to move on our skis. According to the plan of the offensive, my battalion was to develop success for the first battalion of the infantry regiment ahead of us. The initial position of the battalion was in the north of Vanomozero village, and we were to move to the town of Podporozhiye via the village.

The offense progressed very slowly and the Finns managed to repel it. The first echelon's offense choked in its attack. I led my second infantry company. It successfully attacked the flank of the enemy and advanced 600-700 meters where we were delayed by a well- organized defense of the enemy. Our company enabled the first echelon of our regiment to resume their offense and they advanced one kilometer into the rear of the enemy. However, the combat action stopped at this point.

This unsuccessful experience encountered a number of shortcomings. The infantry units failed to progress in the deep snow, in marshy-wooded areas, the lack of weapons, particularly, artillery ammunition, which made firing support rather symbolic than real. In such a situation even a minor detail became a serious obstacle. For example, ski bindings were rather primitive: ropes and sticks, restraining the pace and the skis slid away. In other words, the units were poorly equipped.

The headquarters had poor knowledge of the front and defense lines of the enemy, and many weapons, or artillery emplacements, were unidentified and the combat tasks had no clear definition. Besides, the staff was starved. The only accomplishment of this failure of the offense was that the front line moved 300-400 meters closer to the enemy and enabled better arrangement of the defense. This was at the end of April 1942.

The first battalion under my command replaced the units of the infantry regiment and took defense. There was an impassable swamp on our right and a hill four kilometers away on our right flank. The skies and the earth were gazing at us with a hostile squint.

There was still winter at its reign: frozen soil, cold wind, lack of natural or made shelters. The trenches and other combat positions were arranged in the snow. We weren't allowed to make a fire, and the cold and dampness threatened to eliminate the battalion without a single shot. Breaching the order, we made a fire to warm up and dry our valenki and foot wraps on hill slopes on the opposite side of the enemy.

My observation post was on a tree by the hill marking the right flank of the battalion defense area. It was hard to climb the tree and climb back down. However, it made an excellent observation site.

Once my subordinate Rodimov, commander of the machine gun company climbed the tree with me. It was an early morning, transparent and filled with colorful frost sparkles. The enemy was waking up on the opposite side. We had a good vision of a locomotive dragging few carriages to the front line of the enemy.

It stopped and soldiers with buckets and pots came closer to it. This was the first time that we saw how a locomotive delivered food to combat positions. Rodimov did some thinking and then pronounced, 'Let's disturb them and shoot at them from closed weapon emplacements.' This was an interesting suggestion.

On another morning, I was on my observation post with my stereo telescope. The Finns were as punctual as the Germans. The locomotive approached and I gave an order to start volley shooting of 250 bullets in each cartridge belt. A few soldiers fell on the snow and the others crawled away. We did it again in the morning and afternoon.

The Finns shot a few hundred shells, but with no results since they were shooting at random. It was hard to identify weapon emplacements from that other side. Besides, who could have guessed that our machine guns were shooting at random and at the direction of the battalion commanding officer sitting on a tree! Like Rodimov said we did 'disturb' the enemy. The locomotive never arrived during daytime, and there were no more regular supplies delivered.

I promoted awards to be given to the company commanding officer and gun layers and this experience of shooting from closed weapon emplacements promptly spread all over the division. Every day I patrolled the front line of the battalion. On the morning of 20th April I went to the observation post of Maslov, the commanding officer of the second infantry company.

The sun was hurrying the late spring; there was still snow in the shadow and lower areas. It was damp and wet. All of a sudden a bullet struck beside me. I fell onto the slush mixed with snow. It didn't occur to me immediately that my padded jacket, khaki trousers and my boots made me a visible target. The shots came one after the other. The enemy was drawing a bead on me. I tried to dig into the cold disgusting mess of the snow and soil.

The snow in the Finnish Transpolar area is different, sizzling cold and blinding bright. It was furious and hostile to us, but soft and saving for those who were born and lived here. I finally identified two-three second intervals between the shots. I threw my body to the side. The bullets precisely hit the spot where I had just been. I jumped onto my feet and instantly moved to the 'dead zone' on the slope of a hill. Later, recalling this incident, I felt like being thrown onto a hot pan with the fire underneath. The Finnish sniper was shooting from the neutral zone and was well camouflaged. Lance corporal Yefimov, from Omsk, hunted him down and managed to kill him. I was his last target on which he mastered his skills in cold blood. That's the way it happens at war.

The battalion followed the red line only visible on our staff maps, and there was no alternative to the order. We either had to capture a piece of the enemy's land or die. Breaching an order crossed a soldier out of the lists of the living. Before a battle everything plunged into mysterious silence, each sound strained every nerve, the eyes searched for hidden threat and the beauty of nature went past perception. Soldiers of Russia had always had fighting skills, but the Finns were also good at it, fighting on their own land, on their snow.

There were heroes on both sides of the front. That Finnish soldier was a hero. He chose his weapons emplacement and from the military standpoint his choice was impeccable, he stood up directly against the read arrow of the offense. That soldier was a talented fighter. According to his estimation, however intuitive, the Soviet battalion had to fail to complete its combat mission and lie down on the hot sparkling snow.

Straining our muscles and will, we were advancing in the snow, step by step pushing the front line farther to the west, when all of a sudden there were long bursts of machine gun firing from nobody knew where. One machine gunner could stop a whole company in its flight, if this machine gunner managed to make the right choice for his weapon emplacement and knew his weapon well.

We were 'lucky' the one we bumped into was the right one. The advancement of my battalion was jeopardized. I was looking around the field hopelessly trying to take the right decision. The soldiers were digging deeper into the snow knowing that it was impossible to move forward, and they weren't allowed to move back. The number of the deceased and wounded was growing.

I finally identified his location on the second floor of an abandoned yellow building, one of the facilities we were to capture. It was impossible to get the gunner with a rifle. I tried to imagine him: his age, clothes, mood, and thoughts. I had an ambiguous attitude to him at that moment. 'You skunk, bastard, how do we get you. Let me think and then I will...' And instantly I thought, 'Smart guy, excellent position, one fighting against a battalion and he is no coward. He must have enough bullets and wants to bury us in his land.' We found a passage and completed our mission, but this episode had its continuation.

In the middle of October 1980, the chief of the general Staff of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union Marshall of the Soviet Union, Ogarkov, authorized me to meet and accompany a Finnish delegation headed by the chief of the Military Academy of Finland, General Settele.

[Editor's note: as after transforming from Cyrillic version the spelling of this surname can be various (i.e. Sattala, Setele), we have no information about this general.] The General was a sociable person. The Finns wanted to get familiarized with the teaching experiences of our military higher educational institutions. They visited a number of institutions and we were to visit the higher academic course 'Vystrel' in Solnechnogorsk, the one that I finished in 1941.

My interpreter was late and I decided to drive in the car with General Settele with no other company. I could speak a little English. He told me about his life. He graduated from the Military Academy in London and was a private during World War II. I told him about myself and we had a nice conversation, when he asked me, 'How come you, General, know Finland so well?' I replied that I had been fighting against the Finns from late 1941 till middle 1942. He looked surprised and said that he also fought in this area against the Russian troops.

Naturally, I asked him in which area exactly and he said, 'Between the Ladoga and Onezhiye, on the Swir' River.' I was surprised to hear this as this was where I was, near the power plant Swir'-3 and the village Lodeynoye Field. He told me the stunning truth: 'I was a machine gunner.' I told him how one machine gunner disturbed us with the bursts of fire from the second floor of a two-storied bright yellow building.

And General Settele told me this was where his position was set. This second meeting with the Finnish military had negative consequences for me. I wasn't supposed to talk to a foreign general without an interpreter or other witnesses. Our driver didn't know English and my direct management grew suspicions about my political position and I got into trouble with certain authorities.

In early March 1942, my infantry battalion was shielding the 'Road of Life' on the bank of Ladoga Lake. I got an order from the regiment commissar to leave the defense site and relocate to the vicinity of the town of Lodeynoye Pole. Before morning, the battalion reached the forest south-west of Lodeynoye Pole.

At dusk we started on our ski march. In the evening I ordered the battalion to line up when I noticed that most soldiers and officers walked as if they were blind. I started talking with them. My battalion assistant doctor told me that lack of vitamins caused the so-called night blindness. I thought it over and decided to line them up in columns of twos.

I was at the head on the right and the senior political officer was to march on my left. The Chief of the battalion staff was to rig up the rear. The battalion was to follow us in two chain lines with their ski sticks connected to one another.

We covered 100 kilometers in three nights. The division commander and the commissar were startled to see this unusual march. For a week we were given chicken liver and everything else until the disease had disappeared and the battalion continued its march through the war.

In spring, scurvy affected the battalion. This happened after an unsuccessful offense. We stopped. There were pine woods around. We boiled pine branches and drank this herb. My teeth were actually decomposing. I was taken to a hospital where I had to stay for ten days. I had beetroot syrup applied on my gums. We had a lice epidemic in winter 1942.

My shirt was actually 'breathing,' when I took it off. This was terrible. We tried to shake our underwear out in the frost, but it didn't work. Sanitary disinfection units arrived at my battalion in early April. They deployed a sauna, which soldiers called a 'lice killer.' They destroyed our clothes and we received new ones.

We didn't have lice ever again during the war. We often arranged sort of 'saunas' in tents. We heated water over the fire and then jumped into a lake. We had sufficient laundry soap, but we didn't have sufficient tobacco. Soldiers brought herbs from haystacks in the neutral zone and we smoked it, but some desperate guys smoked tea leaves. This was a drug. Many of those, who smoked it died young.

The years 1941 and 1942 were the hardest. The situation improved in 1943, particularly when American food supplies became available: tinned meat, marinated tongues. It helped us a lot and also, our suppliers learned their lessons and arranged better deliveries.

My part was hard: I was responsible for the people's lives. Things happened. Being chief of the staff, I was responsible for surveys. My guys and I brought prisoners in broad daylight with no losses. I had about 18 reconnaissance men. It was July, the grass was knee-high. Our reconnaissance guys were taking training, when finally they invited me to watch their skills.

I sat on a hill and was to try to identify them. Half an hour passed and I noticed no one, when all of a sudden Seryozha Chimbarov, a reconnaissance guy, grabbed me on my shoulder. So, they crawled as far as the hill I was on and I didn't discover them.

Two days later they went to seize a prisoner for interrogation. They crawled to the territory of the enemy, crawled under the barbed wire, cut it and got into a trench. We knew that the Germans changed their shift watch every two hours. They captured a huge tall and strong Swede, 1.9 meters tall. The Swedes, born in Finland, served in the German army. He was disassembling his watch, when he was on guard. Our guys gagged him and dragged him onto our territory. This Swede provided good information to us.

In 1944, I was fighting in the vicinity of Kandalaksha. My frost-bitten feet often remind me of this period where the endless snow of 1.5 meters or more covered the plains, hills, lakes, woods, roads and mountains. One disappeared in the snow, when stepping off one's skis. There were boulder stones on the ground making holes in the valenki boots. The snow got inside and froze one's feet.

In February 1944 the 21st Perm infantry division, relocated by railroad from Volkhov station to the vicinity of Kandalaksha station where the 19th army of the Karelian Front was taking defense. The Transpolar area was extremely inhospitable at this time. There was deep snow; the daylight lasted five hours, impassable areas, etc.

At this area and at this period of time someone on top who probably thought he was a strategic genius, decided to conduct an offensive operation in the direction of Kandalaksha where infantry corps of the German Laplander Army were deployed.

After scouting the area I left a walk reconnaissance squad under the command of a junior lieutenant, Ian Kaizer, in the intended initial position for the attack of our regiment. We returned to the location of our first battalion late at night, delayed by the enemy's artillery barrage and darkness.

The scout group couldn't move fast on skis. Besides, a few people were wounded with shell splinters. The following afternoon I received an order from the chief of the division headquarters to instantly move the battalion to support the front line units: two battalions, of the division fighting in the encirclement.

My mission was to break through the encirclement, deliver ammunition to the units and straighten up the front line. It should be noted here that Captain Bazilev, our division commander, never lost his heart, he was always cheerful, young and very handsome. Besides, he had an expressed military talent. It's nice to have such a partner and you wouldn't mind beating even two armies having him beside you.

We joined his battalion and headed to our destination on skis. We were to cover a few kilometers on skis. We approached the 'Veno tunturi' where the front line unit was fighting, when it got dark. [Editor's note: 'tunturi' means 'hill' in Finnish, but we can only transliterate its name from how the interviewee pronounced it in Russian. There is no hill under this name in Finland.] The reconnaissance guys reported that there were Germans in snow trenches on the slopes of the Mountain.

I had no connection with the division headquarters and no artillery coverage, accordingly. Having assessed the situation I decided to attack in the dark. Bazilev and I lined the battalion. It rushed to the attack at the signal flare firing from our machine and automatic guns. It came unexpected for the enemy and it was dispirited.

We captured about 20 prisoners and the rest of them scattered around to the flanks. This was a complete and bloodless victory for us. We delivered the ammunition, dried bread and tinned meat to our unit. We fulfilled our mission. A reconnaissance guy and I took some rest in a cavity on the slope of the mountain.

About an hour later a messenger of the commanding officer of the front line units found me. The commanding officer wanted to discuss further steps with me. I left our shelter for about one and a half hours, but when I returned the soldier was no longer there and the shelter hole turned into a shell pit. The shell hit this spot 15 minutes after I left it... I was put forward for an award along with the battalion commandment and the distinguished soldiers and sergeants. I received my first order: an Order of the Combat Red Banner 28.

Spring came surprisingly early in the area of the Drava River in the south of Hungary in 1945. It was just the beginning of March, but the ground was dry and there was green grass growing. The war was nearing its end and we were thinking about the peaceful life.

The situation was hard, however, with the third Ukrainian Front that our battalion was assigned to. The German commandment wanted to gather all forces to keep Soviet troops from breaking through to Vienna. The Germans suddenly struck a blow on the flank of the division where I was chief of the headquarters.

The divisions adjusted our combat mission. On the morning of 9th March, after a 40-kilometer march, the division headquarters and I arrived at Gordisa settlement. The division units went to the battlefield right away since the Germans were rather successful on the Drava River on the border between Hungary and [former] Yugoslavia where the Yugoslavian and Bulgarian forces were in defense.

On the afternoon of 9th March, the chief of the headquarters of one of the Yugoslavian armies accompanied by a colonel from the headquarters of the third Ukrainian Front arrived at the command post of the division. They requested one infantry regiment for closing a gap in the defense near the town of Beremend.

I agreed since the combat situation demanded to do this. However, I had to contact the division commanding officer. I decided to report this situation to the corps commandant who gave his consent. The 420th Red Banner infantry regiment, which had just arrived, was sent to the vicinity of Beremend. The regiment and a Yugoslavian partisan brigade threw the enemy back to the Drava River.

However, the Germans managed to established strong defense and attacks of our infantry regiment who had no success. On 10th March another regiment arrived and joined us. By the morning of 11th March, both regiments were ordered to throw the enemy onto the opposite bank of the river.

I was ordered to coordinate the actions of both regiments. At this time I had a battalion under my command and the acting chief of staff of the division since its chief had perished. I was responsible for the division strategy, its movement and actions. I reported to the headquarters of the regiment. Early in the morning, I surveyed the area from my observation point and I knew that it was going to be hard to fulfill this mission.

I had to run one-and-a-half kilometers from one shelter to another to get to the observation post. The ground was soft, as if covered with a feather mattress. Upon agreeing on coordination issues we received the battalion commander's approval of the attack.

After a short artillery preparation the battalions moved forward. In less than an hour our left flank battalion broke into the town, but had to suspend its advance. The right flank battalion was lying down on the road. We decided to move the observation post closer to the front line. I remember asking Danilov, 'Have you got something prepared?' He replied smiling coolly, 'Hey, we shall think of something!'

We moved on crawling and running across ditches and high dry grass. It would have been astonishing, if the enemy hadn't discovered us. Having covered about 500 meters, Danilov and I happened to come to an open field under the machine gun firing. We took our digging spades hoping to make some sort of cells to shoot back.

There were about ten of us in the group. We had no place to hide. We couldn't move back either since the battalions might misinterpret their commanding officers' maneuver and follow their example. Even a small trench needed time to make. The enemy wasn't going to wait till we dug trenches. Its artillery shells were exploding closer and closer.

Danilov was about three meters from where I was in hiding. He raised his head, gave me his calm and charming smile, stood up abruptly and yelled, 'Go a few meters ahead where our communication guys have dug a hide-out!' This was a decision of a real regiment commander. At that moment a shell exploded beside us. It was destined for us. My conscience grew dark and I was thrown onto Danilov.

When I came to my senses, I saw that his leg was smashed above his knee and bones and flesh were burnt into some horrible mix. His face had turned as white as a cast mask from the shock and loss of blood. There wasn't a scratch on me. The German artillery firing never stopped. The regiment political officer and I dragged Danilov to the hide-out of our communication guys and applied a tourniquet.

Later the communication guys moved the commander to the medical units. He survived, though he became an invalid. He returned to Moscow and got married. We were very good friends after the war. Regretfully, he died in the late 1970s.

I took command over the regiment. In the evening we reunited with the units of the second regiment. My division commander ordered me to return to the division observation post. Our 122nd infantry division and the rest of the front in the north of Yugoslavia were fighting in the vicinity of the Mura River in the direction of Maribor [today Slovenia, then Yugoslavia] and further to Zagreb [Capital of Croatia, then Yugoslavia].

The 12th of April 1945 started as usual. There wasn't any sign of trouble. The day was warm and nice. The division fought successfully on the left flank of the 3rd Ukrainian Front between the Drava and Mura Rivers. At night I ordered the arrangement of a new observation post for the division commander one kilometer from the front line, on a hill, from where the whole disposition could be viewed.

By the afternoon the observation post was already operational. The division artillery commanding officer, the corps artillery commander and other division officers were there. Lunch was provided at the bottom of the hill and the division commander ordered Ogarkov and me to go and get lunch. We were having lunch, and it was approaching 4pm and the sun was setting in the west. On our way back to the observation post we bumped into the artillery regiment commanding officer and talked shop with him. Then we moved on and I was following Ogarkov. The moment he stepped into the trench leading to the observation post, the artillery firing began.

I heard Nikolay Vassilievich Ogarkov speaking with pain in his voice, 'Ouch! My legs! I can't feel them!' I bent over and saw his boots full of blood. I carried him on my shoulders down the hill where there was a hut. Our division commanding officer was there with his side blood- stained, the corps artillery commander with his left leg wounded, a telephone operator with her right hand hit by a splinter and the division artillery commander with his face blood-stained. I left Ogarkov with the nurses and it occurred to me that there was nobody left on the observation post, the division was out of command! I rushed to the observation post to take command of the battle. The moment I stepped into the trench, it wasn't a fatal spot. A fiery 'tulip' grew two steps away from me. I fell and touched myself. Everything was all right. Later I realized that I had fallen at the moment when the shell splinters were still flying.

In Romania I met with the Jews who had lived during the German rule. I also met with Jews in Hungary. They requested me to provide trucks to transport the Jews from concentration camps. I met with former prisoners of concentration camps. My division commander stayed in a Jewish house in Pecs. His subordinate brought me his message to go and talk to those people. I spoke Yiddish to them and they told me about the hardships they had gone through.

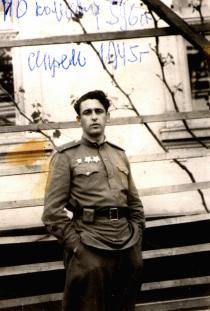

I was at the southern border of Austria at the time, when the war ended. On 12th April, Urgen [a town in Tyrol], was captured by the Americans. We felt the situation was changing, and the victory was close. Since our regiment commander was wounded I was appointed commanding officer of the regiment.

The regiment was under my command from 20th April till 7th May, when a new commanding officer was appointed. On 8th May we were preparing for relocation, but our corps commander ordered everyone to switch on their radios. The regiments were on their way, when the radio announced that the war was over. The corps commander ordered the regiments to stop and prepare for a parade.

This was the first time in my life that I witnessed the rear guys providing full dress uniforms to the division within six hours. We had the Victory parade on the border of [former] Yugoslavia and Austria. Later we relocated to the vicinity of Baden [near Vienna].

Our units were engaged in the construction of training camps, guarded a palace in the Alps, hunted for German deserters in the mountains and we also hunted for our bastards involved in raids. Many things happened. I shall not dwell on black pages of the good story. On 23rd May I got an invitation to the Austrian city of Graz, to the university; my friend Ogarkov was also invited, and so was Colonel-General Sharokhin, regiment commander [General Officer commanding the 57th Army in 1944- 45].

Then we met with the commander of the 1st Bulgarian army. [In April 1941 Bulgaria entered World War II in alliance with Germany. On 8th September 1944 Bulgaria declared war on Germany, now as a Soviet ally.] He awarded us Bulgarian orders. In June the famous walking tour home began.

We rested during daytime and walked barefoot across Europe at night. All railroads were overloaded with trophies: cattle, factory equipment, everything that could be removed from Austria and Hungary, and the army units had to walk back home. Our division walked from near Vienna to Zhmerinka [Ukraine].

I left the division after we crossed the Austro-Hungarian division. I was ordered to go to the commission of admission to a military higher educational institution. I was very concerned about my possible failure due to my nationality, when my uncle Yefim helped me unintentionally.

The chairman of the admission commission happened to know my uncle from their former joint party activities, but he didn't know that my uncle had been declared an enemy of the people later. He instantly admitted me to the academy named after Frunze 29 [MV Frunze Military Academy].

- Post-war

I went to study in Moscow. There were five parallel courses with 200 cadets on each of them and that admission was called Stalin's admission. Among its students there were 83 Heroes of the Soviet Union, lieutenant colonels, colonels, majors and rarely captains. They were veterans of the war. I finished the war in the rank of lieutenant colonel; I was promoted to this rank at the age of 23, in early 1944. Our academy took part in six parades during my studies. Its students had various levels of education: from secondary to higher.

The admission criterion was what one contributed to the victory during the war. I was head student in my group. There was a major, a Hero of the Soviet Union 30 in my group. He just had elementary education. We studied foreign languages and he studied Russian. I studied English. I enjoyed studying it. Upon obtaining approval of the director of the academy students could obtain diplomas in a foreign language.

There were seven Jews in the academy. Frankly speaking, we didn't face any prejudiced attitude. There was postwar fraternity. However, later I faced anti-Semitism. I was to finish the Academy with a gold medal. During my graduation exam on the history of the Communist Party I forgot what issues were discussed at the 5th Congress of the Party. I had excellent marks in all subjects, but I was almost on the edge of getting a 'three' in this subject, but my examiners felt sorry for me and gave me a 'four'. [The marks go from 1 being the worst to 5 being the best.]

I graduated from the academy in 1948. I wanted to continue my studies in the Military Diplomatic Academy, but I failed to enter it, and I understood that this happened due to my Jewish identity. The Academy graduates became military attaches, reconnaissance officers and embassy employees. I was also affected by my Jewish identity, when the struggle against cosmopolitism [Campaign against 'cosmopolitans'] 31 began, when my Jewish friends were sent away from Moscow, to military units in remote areas and were demoted.