Naum Bitman

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Vladimir Zaidenberg

Date of interview: February 2002

My name is Naum Shykovich Bitman. I was born in 1937 in Kiev. My parents: father – Shyko Bitman and my mother – Basia Bitman ( nee Shub).

I have no information about my father’s parents.

My grandfather’s name was Teviee (my mother’s father). His last name was Shub. I don’t know where he was born, but he was living with his wife and children in the town of Zhytkovichi in Byelorussia. In 1921 they moved to Kiev.

Zhytkovichi was a far away place. There lived Byelorussians, Russians and other nationalities along with Jews. They were living there peacefully. Almost half of the population was Jewish, but mamma often repeated that they had never felt any disparage or discrimination. Mamma attended school and heder.

The people in town respected grandfather Teviee very much. He was a shoihet - cutter. He studied his trade in Warsaw and received a diploma. He could slaughter poultry and cattle. The capability to slaughter cattle was especially respected. The people, Jewish, Byelorussian and Russian among them, keeping cows, bulls and poultry were addressing my grandfather asking him to do his job.

My mother said they had a house of their own. It was a small wooden house. I don’t know how many rooms there were in the house, but it was good to have their own house. I cannot say what they had, but I know that although they were not living in luxury, my grandfather’s work enabled them to be relatively well-doing. He was given meat and was paid well for his work. They were not in need of anything.

Grandfather didn’t have any assistants – he worked alone. Grandfather was religious, as his work required following religious rules and traditions. However, I cannot say how deeply religious he was, as I didn’t know him. As I have already mentioned, he studied in Warsaw. Here is what happened to him once.

He came to Warsaw. It was a big town. My grandfather liked many things about it, and many of them he saw for the first time in his life. He had his picture taken in Warsaw. Then he went to Zhytkovichi and showed the picture to people. They were shocked, and the only thing they could say was: ”He bought a picture in Warsaw, and the person in the picture looks exactly like Teviee!” They didn’t understand that it was possible to be photographed. This can give you an idea how distant from civilization this town was.

Things went well until 1918, when all kinds of gangs (the gang of Zelyoniy – the gang leader – and others) started coming across this area.

I am only aware of one episode, very hard for us, the one that actually caused my grandfather’s early death. Mamma often told us about this. Few bandits captured my grandfather and said “We shall cut off his ears”. That’s what they wanted – just to cut off his ears. The whole family was in such panic that they had to turn to other people for help. Somehow they all stood for grandfather and rescued him. They told the bandits how grandfather was always helping all people – Jewish, Byelorussia and other people and how much he was respected and loved.

That was generally a quiet location and the bandits just happened to come across that area. But my grandfather didn’t live long after this. He had died before we moved to Kiev in 1921.

They might have been living in that little town much longer, they might have remained there. But then the first gangs started coming over this area and the bolsheviks followed them, throwing out of their homes into the streets a number of Jewish families, including my parents’ family.

Some relative offered shelter to them. But it was such a tragedy for them. And it was particularly hard for my grandfather, as he was the head of this family. He had six children by then, and the family was homeless. He couldn’t endure the fact of it and died in 1918. I don’t know exactly how old he was, but he died young.

My grandmother’s name was Haiya, her last name was Shub (nee Serebrianaya). Grandmother was born in 1886 in Zhytkovichi. I know that she had brothers and sisters. But I only know her younger brother. His name was Lev Serebrianiy. I don’t know what he was doing before the war, but after the war he lived in Lvov. I don’t know what his position was, but his work had to do with the return of Jewish people from other countries after the war. Many of them didn’t want to come back, believing that they would be subject to repression. Lyova was arrested. He was charged for intentionally keeping the Jewish people from returning to their Motherland. He was sent in exile on Kolyma and spent over nine years there. He returned home after Stalin’s death.

My grandmother had a cousin Sarra. She left for Palestine in the twenties. At that time it was easy to go. Later she participated in a beauty contest in Paris and won the first prize. This story continued after the war. Once we received a paper from the Red Cross. My grandmother's sister was looking for her. We all felt happy, but then we remembered that all those who corresponded with their relatives underwent repression and arrests. So, my grandmother was afraid to answer. She never wrote her sister Sarra until the end of her life.

As I have said the bolsheviks coming to Zhytkovichi put an end to the people’s quiet life, bringing a wave of anti-Semitism. My grandmother had a prayer of her own. Looking at what was happening around she always said: “Ah, melihe, melihe…”[this is translated "power", life was very difficult]. She understood at once what those people in power were like and that no good could be expected from them.

Well, after my grandfather’s death my grandmother remained with six children and no means of existence or a home. They moved to Kiev in 1921.

The oldest sister Asia Shub was born in 1905. After her came brother Zalman (Zelik) Shub, born in 1906. Then was brother Shelik, or Sasha, born in 1910. Then came my mother Basia. Mamma’s younger sister Dvosia Shub was born in 1916. And the last one, Gersh, Grisha, born in 1918 some time before my grandfather passed away. We don’t even have his picture.

Mamma’s sisters Asia and Dvosia got married later. Asia kept her own last name and Dvosia took her husband’s last name – she became Tarakanskaya. Asia worked as cashier all her life. During the war the sisters were in evacuation. Then they returned to Kiev. Asia died in 1987, and Dvosia Tarakanskaya is still alive. She lives in America with her son. Mamma’s brothers Zalman Shub and Gershl Shub perished on the front during the great Patriotic War. Brother Shelik was shot by the Germans in Kiev in 1941. Later I will tell about it in more detail.

As it was, the family consisting of six children and my grandmother arrived in Kiev. They arrived in hungry Kiev (hunger of 1921 in Ukraine).

They struggled to survive. We settled down in a building on the embankment. We had a state-owned apartment and I don’t know how my grandmother managed to receive it. The family lived in two small rooms. This was a two-storied building. Our family lived on the first floor. Grandmother realized she needed to do something to survive. And she took to baking rolls. Older sisters (Asia and mamma) were selling them. They Lived in Podol and it was difficult to sell things there. They had to go downtown – Kreschatik (central street) or Bessarabka (central market) to sell their bakeries. There was a streetcar, connecting Krasnaya square (in Podol) with the Philarmonic. But it cost money, and mamma couldn’t afford it. Mamma, to save some money, walked up the hill holding a basket with little pies. They were doing this for some time before NEP [New Economic Policy] was introduced. During NEP it was possible to sell things, but taxes were more than the family could bear. They were poor again. Then they bought a special machine for making stockings. They were selling them at Bessarabka and thus could afford to buy some food. But the children needed to study. Mamma only studied in the primary Jewish school in Zhytkovichi. Later on she didn’t have an opportunity to study. She was reading textbooks while making stockings, and then she passed her entrance exams to the construction school.

Mamma studied very well. Only Ukrainian was difficult for her. Mamma never told me about celebration of Jewish holidays in the family. I don’t think they celebrated any. Six children was quite a load for grandmother. They had enough to eat, but they didn’t have enough money or time to celebrate holidays. Mamma attended Jewish school in her childhood, but after moving to Kiev the family didn’t observe any Jewish traditions or celebrate holidays.

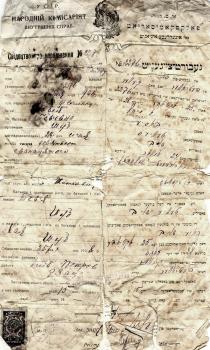

At that time something happened that mamma couldn’t talk about without tears until the last days of her life. People called this period of the early thirties “zolotushki’ (from word zoloto – gold). Authorities needed money. They turned to those who were doing some business during NEP or had a license. Mamma was summoned to come to NKVD [People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs], where they said to her: “Give us your gold”. This sounded ridiculous to her. But they in the police didn’t believe she didn’t have any and put her behind bars, in the basement of that building. She told us later that each coming woman was put in a circle of big women and they pushed her from one to another until the person fell from exhaustion. Mamma was very strong – she had ideal health, but staying at this place affected her health a lot. Her sisters addressed management at the school where she studied asking them to help her. People from the school knew that sisters from this family shared one pair of shoes. They talked to the police, telling them that Shub was their best student, and that they couldn’t have any gold. After that they let her go. This was in 1932.

After finishing this technical school mamma took a job of estimator in Dnepro river fleet.

Mamma told us that she was very fond of the komsomol league activities. She told us about voskresnik (voluntary work on Sunday), their trips to collect the crops, and also, they went to get some gravel. They thought it was a whole world and there was no other world – America, England or Europe. Here was gravel, that truck, difficulties and tribulations – this was their life. They entertained together as well. They went to the beach, located across the street from our home. They sang komsomol and Soviet songs together – they enjoyed it so! That is what mamma told us. Her circle of friends consisted of Jewish people, basically. However, they did not think of themselves as part of the Jewish nation nor were they interested in the Jewish history, culture or religion. My mother said that representatives of different nationalities got along very well.

Mamma met my father during one of such komsomol trips. It might have never come to going out with him, had he not been insistent and even rude. Mamma was dating a Jewish boy at that time. My father met him once and said: “If you keep coming here I will cut off your head”. That guy stopped coming, and in the end my mamma married my father. Neither her sisters and brothers nor my grandmother could treat him as member of the family. He was different, because it was other social and spiritual level. He was Jewish, of course, but different. It was a tragedy for my mother.

My father was born in 1905 in Belopolie village in Ukraine. His name was Shyko Noiyahovich, his last name was Bitman. He came from a family of working people. But his parents had passed away by then. His father had been a carpenter, he had worked in the cultural center “Pischevik”. My parents got married in 1936 and they were living in our apartment. Older sister Asia had already been married by then. Mother and father were living in a 12-meter room. I was born in 1937 and there were three of us sharing that little room. .

I can hardly remember anything from my childhood before the war. I remember my grandmother – she was always taking care of me at home. Grandmother spoke Yiddish with those who could understand it. I remember there was matsa at home. I do not remember any Jewish celebrations at home, but I remember matsa. I liked it very much. Another thing I remember is that they always gave me money at Hanukkah. Mother and grandmother spoke Yiddish to one another, and the sisters spoke Russian.

I don’t remember mamma telling me whether they had known anything about the coming war or about fascism in Germany. She didn’t say a thing about repression in the thirties either. Repression swept over the country. But komsomol members continued their voskresniks and singing songs. They thought everything was as it should be. One thing that mamma told us was about the secret campaign in support of Trotskiy, I believe. He had been sent away from the country by then, and the people were speaking in support of him. Somebody in technical school wanted to involve mamma into that campaign, but she stayed away. She was fond of the construction of socialism and ultimately believed everything the authorities were saying or doing.

The war was a surprise for our family or anybody else. On Sunday, 22 June 1941, mamma was waiting for her friend to go to the beach. We were waiting, too. We called mamma’s friend and she said: “Basia, don’t you know? Haven’t you heard what happened?” And she told mamma about the war. Then they started crying. We had a housemaid, Tonia, a village girl, at that time. When she heard about the beginning of the war, she took me in her hands and cried out: “War!”. I got so scared that I couldn’t talk for about two weeks. And then I was stammering for the rest of my life actually. During my last year at school I took some medical treatment and it helped a little. But always, when I get nervous I stammer, This is a kind of memory that I have of the first day of war.

The family was at a loss – what did they have to do? They were so far from the policy that they didn’t have any idea what fascism or Hitler were about. And they found themselves at the crossroads. They had to decide where or whether they had to leave. They had different opinions. Some thought it was necessary to go and the others were recollecting the Germans in 1918. They were polite then. Grandmother was saying so and it was true. They couldn’t decide whether they should go or not.

Mother’s youngest brother Gershl (Grisha), 22 years of age, had finished DOSAAf (Voluntary community of Army, Air Force and Navy Support school) before the war. Grisha was a driver. They recruited him immediately to support evacuation of officers to our army. Grisha was once driving those officers past Kiev, and he dropped by home for a second. All he could say was that Hitler was killing all Jewish people and that we should leave. He kissed everybody and continued on his way. This was the last time that we saw him. In Darnitsa, near the Paton Bridge a German bomb hit on this bus, killing all of them, including Grisha. Thus, one son died right away. All he managed to tell us was to go away.

The family started preparations to evacuate. Older brother Zalman was called up to the army on the first day of the war and was killed in 1944.

Mamma’s brother Shelik Shub died tragically. He worked as mechanic at the factory of knitted wear. When the Germans were approaching Kiev he decided to stay in the underground to help struggle against them – collect information and transfer it, etc. He stayed in Kiev when Germans came, and during Babiy Yar he was still alive. He might have survived if he hadn’t decided to visit his own home and the yard where he grew up. But when German came some people started working for them and became traitors. As soon as Shelik showed up in this yard, someone immediately informed Gestapo, and motorcyclists appeared there in five minutes. Shelik was captured. They took him to the pier and shot him. Such was the destiny of brother Shelik. But I would like to mention here what grandmother must have felt knowing the person that betrayed her son. After the war he spent some time in exile and returned home. We were living at the entrance to the yard. Grandmother was alive and she saw the man who was murderer of her son passing by every day.

My father was called up to the army and sent to the construction unit. And we started preparations to get on the way. We took only the most necessary things with us. I don’t remember how we got to the railway station. But I remember well what was happening afterwards. It was all very hard for mamma and she often thought about it. The thing is the Germans did not only want to defeat the army. They also enjoyed bringing maximum chaos into the people’s life. We almost went as far as Dnepropetrovsk, seems we went ten or eleven hours, when they started bombing our train. A bomb exploded ahead of us. Mamma understood it was the end of all of us. She took me – I was 3 years old a half – and went into the forest. She thought it was better to die together. But the bombing was over and all of us survived.

Grandmother Haiya, mamma’s older sister Asia and her daughter Natasha and mamma’s sister Dvosia were going with us. So, we continued our trip. I was 3 years and a half at the time and I couldn’t remember all difficulties that we faced. However, I remember something. We lived some time in the east of Ukraine that was unoccupied. My memories of this period are dim. We were travelling in a freight railcar, and we were always afraid to be late during short stops of the train. We were approaching the Caspian sea. I remember big salt mines, like pyramids. It was strange that salt that we usually have on the table could be lying on the ground. Mountains of it. On the way I fell ill with measles, and mamma thought I wouldn’t survive in such terrible conditions. This is what this trip was like, all of it, painful and incredible. I had fever, so, I just wasn’t quite there. I remember them telling me a story and I remember part of it myself. Here is what I remember. Or, to put it more correctly, I was told the beginning of it and saw the end. Older sister Hashke – Asia - was a pretty woman. The sisters were different: my mother was hardworking and intelligent woman. She liked to study. And her sister liked to show off. They always bought one piece of clothing or one pair of shoes, but she was the first to try them on. She was the first to wear new clothes. And she is really very beautiful. There was an officer in the railcar and he started paying his addresses to Asia. He liked her. He asked her where she was going. Asia said it was Nalchik. “Nalchik has been taken by the Germans”, he said.

The next thing I remember was some strange station where we were sitting while the train was moving past us. Then I saw a pillow, blanket, some bundles falling out of the train and mamma and my aunts jumping out of there. We actually escaped death. Someone we knew that was on this train and went on died there, because Nalchik was already in the hands of Germans. All of them who stayed on that train died. And we moved on and came to the town of Frunze, it is now called Bishbek.

We lived in Frunze until the end of the war. I remember terrible heat. It was such a happy feeling to find a current and lie down in it, having your whole body in the water. Another thing I remember were Levitan’s words: “From the Soviet Informbureau..” Levitan announced all political events on the radio, he had a remarkable voice and was well-known by every Soviet citizen. “From the Soviet Informbureau..” – these were the first words in any political information, all political news started from these words.

Mamma worked very hard. She was a laborer. Sisters went to work, too. They also made a vegetable garden of their own to survive. In Kirghizia we lied with a Russian family. I remember the name of the hostess, it seemed unfamiliar to me. Her name was Panna. I don’t remember the relationships between evacuated Jews, our family, Russian and Kirghiz. I only remember my coming home and asking: “Grandma, am I “zhyd”? Somebody must have called me so. I don’t remember her response, but mother and grandmother must have had a discussion. I remember my mother crying and saying that although we ran away from fascists we couldn’t escape from all evil that reached us even there. That was my first lesson of the relationships between nations near an aryk [not natural water channel for irrigating, built by people] in Kirghizia when I was about five years old.

We returned to Kiev in 1945. I was eight years old, and I went to the first form at school # 19 and studied there ten years.

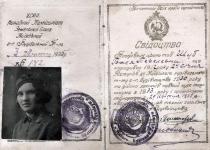

Before we left Frunze my father got a vacation and went to Frunze to visit us. We were not there at the time. Father demobilized in 1945. He was in the construction unit in the army. He didn’t talk much about the war. Once, when I was grown up, he told me that went across the whole country and abroad during the war. But he didn’t participate directly in combat action. He had common awards like any other participant of the war: “For the Victory over Germany”, etc.

Our apartment in Kiev was occupied by our neighbors. They didn’t want to let us in. So we had to fight. We lived with some acquaintances for some time. Later when we moved into our apartment we found it empty – there was no furniture, clothes or utilities left. I remember grandmother saying indignantly: “Why would they need the plinths!?” Generally speaking, our neighbors, who we seemed to be getting along well with before the war behaved like marauders.

But our life was gradually improving. I remember well how we managed without furniture. One would take a carton box, put another one on it, cover it with table-cloth – and there, a piece of furniture was ready! We lived on the first floor. The toilet was outside. But we took little notice of such things. We were happy to be alive.

Wen we returned to Kiev it was a different town and different relationships between people. Same people that were our friends before the war developed hatred towards the Jews. They teased me in the yard: “So, where is Gershik or Shelik?” – those were my relatives, mamma’s brothers that died. I didn’t even quite understand then that they were gloating over the death of the Jewish people. They were saying so about my uncle Shelik that was in the underground and was shot. I believe that it was neighbor Natasha – everybody called her Natka - who told our family about who betrayed Shelik. She knew everything.

She told me some things that I cannot forget. We used to go to the public bath-house. Across the street from it there lived an old Jewish man. For some reason he didn’t go to the Babiy Yar. The Germans came to his home, tied him by the legs to their motorcycle and kept pulling him, his head hitting on the pavement until he died. Just killing a Jew wasn’t enough for them, they wanted to torment them publicly. Natka told me about this terrible happening when I was eight years old, but I still remember it.

Father was in the army for some time in 1945. I remember him coming home riding a horse. We even have a picture of him on a horseback. After demobilization from the army he returned to work in the club of food workers where he had worked before the war. Later he worked in commerce and then - at a gas station.

Mamma went to work in the fleet again. I remember her wearing a uniform at work. The youngest Dvosia that was affectionately called Doushke, took a job in the canteen at Kalinin plant. Aunt Asia also went to work at some store. She didn’t have any profession. Mamma was the only one who had education.

Grandmother Haiya was living with us. Every day she saw the person that betrayed her son to the Germans. This was eternal torment for her. Grandmother lived until 1964.

Grandmother spoke Yiddish to all that could understand her. And I must confess that I felt ashamed if Granny spoke Yiddish at home in the presence of my friends. I was so ashamed. I didn’t know where to put myself. That was what the system did to us – that people were ashamed of their own mother tongue. When I grew older I went to the Caucasus and I saw smaller children speaking Georgian, Azerbaijan. And I began to think why my Granny’s mother tongue seemed such a burden to me. I understood Yiddish a little but I couldn’t read or write

When I grew older I tried to figure out why the word “zhyd” was so widely used to abuse the Jews. Podol where we were living was historically the place where many Jewish people were living. And so, we had about 80 per cent of Jews in our class and for some time we didn’t feel any anti-Semitism because there were quite a few of us. Eizenstein, Rubinstein, Golberg were my classmates. Then it occurred to me that when it was said: people, friendship of the people, we all went through the war – Ukrainians, Russians, Byelorussians, Lithuanians, Uzbek – they never mentioned Jewish people. Not even as an example. It happened so that there was a small group of Jewish students in our class – about seven of us. We were friends, spent much time together, but we never spoke about our nation then. Nobody talked about Babiy Yar then. If, for example, somebody asked: “Where is Zhenia Goldinova?” – “She went away to Babiy Yar”. This could only be said in everyday conversation, and with lowered voice. Nobody said then that Kiev was a place of mass tragedy like Treblinka, Auschwitz, Buchenwald.

In 1951 my younger brother Yephim Bitman was born. There were already four of us living in that 12-meter room.

Now I am surprised at our complete unawareness of what was going on in our country. There wasn’t even a hint to guess. We went for walks on the embankment and we had discussions, but never did we talk about the repressed or exterminated people. Much later I learned about the “case of doctors”, struggle with the cosmopolites when they put that time in the open. Maybe we didn’t subscribe to newspapers in our family – I don’t remember. But it is true that neither my friends nor I ever talked about something we were not supposed to know. Perhaps, we were afraid of each other. This generation got used to be silent, you know. Osip Mandelshtam, a great Soviet poet, a Jew, that was repressed and perished, wrote in a poem that we did not feel our country under our feet and were talking so low that our voices were not heard in 10 steps’ distance.

I remember when Stalin died I didn’t feel either like mourning or grieving. We behaved the way we were expected to, expressing deep sorrow. I wouldn’t say we felt gladness either. It was neither joy nor grief. Our family just took it as death of the first person after Lenin. We never thought that he caused so much suffering to the Soviet people. But grandmother just kept saying: “Ah, melihe..” ["power"].

Although there were quite a few Jews among my friends we all spoke Russian to one another. Nobody knew Yiddish. We didn’t know either the national culture or history but at least nobody called one another “zhyd”.

In 1955 I finished school. We knew in our circles that a Jew practically had no chances to enter an institute in Kiev. Again, we never mentioned this in our discussions, we just knew that one had to go to Novocherkassk or Kursk or Bryansk if one wanted to study in a higher educational institution. One needed acquaintances that would support him or have a birth certificate reissued. We knew what it meant to be a Jew in this city or in this country. It didn’t make sense to discuss it, we just knew that one wouldn’t get a job at the Arsenal plant [Arsenal - one of the most large wailled plants on Ukraine, executes an order defense industry], for example. It was all clear to us, you know. At that time there were shops that manufactured smaller products – haberdashery, hardware, etc. These shops were a kind of ghettos employing Jewish people...

I wanted to continue my studies, and I even tried to take entrance exams. But I noticed that the moment they heard my last name their attitude changed. It was next to impossible for a Jewish person to enter a higher educational institution due to the quota for Jewish students. The Jews did enter – I am not trying to say that Jewish people did not study. I’m just saying that of two people (Ukrainian and Jewish) with equal knowledge the Jewish person had no chance to be accepted. I entered the extramural department at Kiev technological institute of food industry named after Anastas I. Mikoyan. I studied well. However, at some faculties there were staunch anti-Semites, and it was impossible to pass exams at their subjects from the first. But I managed to graduate from this Institute in 1961.

I studied at the extramural department. To study there I had to submit a certificate, confirming my employment. Therefore, I had to get a job. It took me some time to find a job of a technician or lab assistant with the minimal salary of 400 rubles. As soon as they heard my last name at the human resources department they said that the vacancy had already been taken. I remember my visit to Kiev Institute of food industry machine building. I didn’t quite look like a Jew then. Director, hearing that I studied at the Food Industry Institute said it was good as it followed the direction of their Institute. He asked me where I lived to make sure that I didn’t need an apartment. Director told me to fill in the application form and submit it to the personnel department. He also told me to ask the head of that department when I had to start work. And I, going backwards to the door, thought: “That’s good luck. I’ve got a job”. It was like a miracle, yes. I was at the doorway when Director asked my last name. The moment I pronounced it he said: “All right, then. Come back in about two weeks”. Now filling up the form or starting work were out of the question. I understood everything and left. This was some time in 1958-59.

Until my graduation from the Institute I worked as oilman at the motorcycle plant. I worked in the molding shop and there I trained to be a mechanic. After graduation I found out that they were opening an institute for special type of print – on tin, stereoprint, etc. This was Kiev Special Affiliate of the Soviet Union Scientific Research Institute of polygraphy for special types of print. This Institute employed me, they had a very loyal attitude towards Jews, and there were quite a few Jewish employees there. Director was a very honest person. I worked in this Institute my whole life. During my first years I was just learning. And when I got the feeling of all specifics of this work I just plunged into it. I decided to go to the post-graduate school. I had many publications, patents and I entered the post-graduate school in the head Institute in Moscow. I defended my candidate thesis at 37 years.

My father died rather early, in 1964. Mamma wasn’t working by then After my younger brother was born she became a housewife. Grandmother Haiya that couldn’t come to terms with my father. She lived just few weeks longer than my father and also died in 1964. Before the most deaths in 1997, ma a vein in Kiev. Helped we live, brought up our with the brother a children.

My personal life, basically was not good. I got bad luck twice. It was bad luck indeed. I wanted to have a good life but I failed. I met a girl in 1964. I liked her very much. Besides, she was Jewish. She was 7-8 years younger than I was. It was important for that age. I was 26 and she had just finished school. Her name was Victoria Sapozhnikova. We got married and had a wedding, common, mundane wedding in restaurant. All our relatives and friends attended it. Victoria was a very pretty girl. She was wearing a lovely white dress and everything was just fine. In 1966 our son Valeriy was born. But we didn’t have a good life. As I said Victoria was a very pretty girl and I loved her dearly. But she didn’t like the idea of family. She loved to visit people and show off her new dresses. However, family is something different. But Victoria didn’t understand it and didn’t want to do the housework. Perhaps, I was wrong somewhere as well. We got a divorce in some time, but I suffered a lot. Later I got married a second time. I married a Russian girl that came from Lvov. My second marriage failed, too. My second wife met all my requirements to the wife and hostess of the house, but. In this case I must have taken attraction for love. I grew totally indifferent to her in the course of time. And I can’t live in marriage without love. We separated.

I had two children in my second marriage. Older son Vadim was born in 1975. His last name is Kulpinov (he took his mothers’ last name). My son lives in Kiev, but we have nothing in common, we just do not understand one another. Perhaps, he couldn’t forgive me divorcing his mother. My daughter Veronika Kulpinova, 1981 of birth, meets with me regularly. We are friends and she lived at my place a few years.

I don’t think she identifies herself as representative of any nationality. Se has a very loyal attitude towards the nationality that I belong to - Jews. But I never noticed that she was eager to learn something about the Jewish culture or history or study at Solomon University rather than Slavic University. She entered the Slavic University and studies successfully there. My daughter also must think well of Israel, but she cannot have that heady feeling just from the sound of this work, the feeling that I used to have in those years and still have.

My first wife Victoria married a Jewish man and they emigrated to Israel. They failed to make a good life in Israel. I don’t think this happened because they faced some objective hardships. They were just very different people. The three of them – Victoria, her husband and my son Valeriy moved to Germany. Hoping that life would improve. There she left her husband. I keep in touch with her., we are friends. She meets with other men but I remain her friend. I even visited her and my son in Germany.

My son married a German girl and he got adapted to life in Germany. My son identifies himself as a Jew, he loves Israel and goes there almost every year. He probably took this anxious attitude towards the Jewish state from me. I understand that one may want to ask me why I never left Israel considering such attitude. It would not be easy for me to put it into words. I have been interested in Israel and I was glad that Jewish people formed their own state over 50 years ago. In 1957 I went to the Festival of youth and students in Moscow on purpose. I met there members of the delegation from Israel, I traveled with them in their bus. We took pictures and I asked them about their country. I didn’t care that it was dangerous to do so in those years. There was State Security Committee (KGB) watching everybody and I could be punished. But I didn’t care then. I was happy to communicate with real people from Israel. There were several reasons why I hadn’t left for Israel: my mother that didn’t want to go, and my Russian wife that didn’t even want to hear about leaving for Israel. Well, it happened so that I never left for Israel and was never happy in my private life. And now, I believe, it is way too late to go to Israel. One has to go there when one is young to be able to do something for your country.

Young Jewish people take great interest in Israel, they study in Jewish schools and lyceums. There is a number of Jewish organizations for younger people. And those young people that go to Israel now are much closer to the traditions and culture of this country learning them in Ukraine. Of course, I am concerned about the political situation around the country, actually the war, led by terrorists. But this issue will probably be resolved some time and there will be peace there.

I have lived alone in the recent years. My mother Basia Bitman (Shub) died in 1997. Mamma’s sister Asia that lived in Kuntsevo in Moscow died in 1987. There is only mamma’s younger sister Dvosia living with her children in the USA. I have a picture of Dvosia near her house in Kuntsevo. My younger brother Yephim lives in the USA.

I take absolutely positively those changes that perestroika has brought. It is for the first time that one can talk freely and not be afraid of doing or saying something wrong. One can feel free. Of course, life is not easy, but I do not miss the Soviet system that guaranteed cheap sausage to all with no freedom whatsoever. The Soviet system was very hard for me. I believed it to be odd and terrible. One could only compare it with Germany when Hitler was its leader.

I have a positive attitude towards independent Ukraine. However, everything has different sides. For example, I’m a little concerned about suppression of the Russian language and TV Russian programs. There are problems with crossing the border – I mean problems with the customs. However, the country must live an independent life with its own government.

Attitude towards Jewish people has also changed in Ukraine. Maybe its not the people’s attitude but the level of democracy and civilization when one nation wouldn’t be tormented by another.

Synagogues function freely in Ukraine, Kiev, in particular. There’s a Jewish culture community, Israel cultural center, and charity organizations. I can read a number of Jewish newspapers that are published in Ukraine. I am very happy about the Jewish community and cultural life in Ukraine. However, I haven’t identified myself in this life. But let us be optimistic and look into the future with hope. I might even see the land of promise – Israel some day.