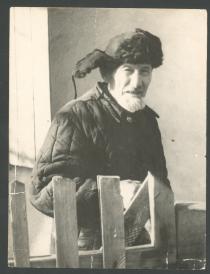

Mark Abramovich lives in a distant northern part of town in a modern multi-storied building in the apartment of his elder son.

From the window you can see a large field, Koroleva Street and the adjacent apartment blocks, very similar to the one in which Mark Abramovich lives.

The Meilakhs’ apartment is on the sixth floor. Standing on the balcony, Mark Abramovich showed me a children’s library not very far from his house and

said that two years ago he was still able to go there almost every day and read newspapers.

Kids visiting the library, having learned that Mark Abramovich was a historian, consulted him on their lessons and essays in history,

and the kind, old man enjoyed helping everybody. For quite some time now Mark Abramovich hasn’t left his home,

only moving around the small three-room apartment. A small, ten square meter room is both his study and bedroom.

All wall-cases from the ceiling to the floor are filled with books on history.

On his desk there are a lot of papers and folders with written works and articles by our interviewee and scientific literature that he reads.

Centrally located on his desk is a big color portrait of his spouse, taken when she was young, that inspires Mark Abramovich and helps him in his work.

There are several bottles of medicines on the table, but there is no smell of old age in the room

– everything is clean and tidy and looks natural and cozy. Mark Abramovich is used to working in simple surroundings.

He possesses a wonderful sense of humor and is joking a lot during our interview, smiling at me with his kind and clear, gray eyes.

He has a vivid expression and a high, wrinkled forehead. I was surprised by his hands,

as they don’t look like those of a 93-year old man: he has long fingers of a strong man’s hand with large accurate white nails.

Life under the communist regime

Family

I was named in honor of my deceased insane uncle. My officially registered name is Motel Avrumovich, but in everyday life people used to call me Mark Abramovich 1.

My paternal grandfather, Gersh Meilakhs, died in 1923 in the town of Tyrlitsa, Monastyrischi district, Lipovetsky region of Kiev province. In his childhood my grandfather studied in a сheder. All Jews without exception studied there. If it was a son of a poor man, the community paid for his schooling. And what was paid to the teachers was considered to be money just to support them, not payment for the schooling itself. Because money can’t be taken for the word of God. Children were taught free-of-charge. Grandfather wore everything that tradition required: a beard, payes, a long frock coat, a lapserdak [upper man’s coat; an old-fashioned long frock coat made of cheap rough wool] and a hat.

Grandfather and Grandmother were especially religious, they observed absolutely all Jewish traditions: kosher food, Sabbath, they went to the synagogue every day. My grandmother didn’t wear a wig, it wasn’t generally accepted then; women would just cover their heads with kerchiefs. Men would wear caps or hats. There was only one cap-maker in Tyrlitsa, and hats would be brought from the town and sold in the settlement. Also, they celebrated absolutely all Jewish holidays at home. Nobody in their family ever changed their names [to Russian ones].

Grandfather couldn’t read or write Russian and didn’t think of politics. The only big boss for him was the policeman. He paid him three-five rubles bribe each month for him not to shut down his store. When Jews were prohibited from running stores, the license was registered in the name of a peasant they knew. He got ten rubles a year for it. And on market days the peasant’s son used to sit in the store, a twelve-year-old boy, who thought it was his store. That’s how they deceived Nikolai II [Russian Emperor]. Their relations with neighbors were very good. In our settlement there were only Jews. And the Ukrainians lived all around us. The attitude towards each other was really very warm. And in time of pogroms 2 they protected us. We ran to the peasants and they hid us and then they would go out and ask the bandits to leave.

People had rest only on holidays. Holidays and Saturdays were strictly observed, it was a rule. On Friday absolutely everyone attended a banya [steam-house; it was not a mikveh or a ritual bath]. If it was a summer day and the market place was close by, say, in the next village, people went there, but tried to return in time for the banya, and in time for the synagogue. Every regulation was observed very strictly. It was engraved in my memory from the age of eight-ten. Children weren’t taken to other settlements. They would study in сheder from five in the morning.

I don’t know whether Grandfather Gersh served in the army or not, there is no information about that. I have no detailed data on Grandfather’s family, because since 13 years of age I lived outside my family, being a student. Grandfather helped Grandma to keep the house and manage the store. They spoke Yiddish and Ukrainian with each other. The topics of conversations were mainly domestic. They read nothing; they were illiterate. They only knew all prayers by heart.

My grandmother Meilakhs, obviously, was born in the same place, in the town of Tyrlitsa, Monastyrischi district, Lipovetsky region of Kiev province. Grandmother died approximately in 1927. She lived about one hundred years. That means she was born in about 1827. She never heard of doctors, never was sick with anything. I have no information about her relatives. She had no education; girls weren’t accepted for schooling. She was very religious: celebrated all holidays, read prayers. The prayers were in Hebrew, but the women didn’t know the translation. They understood only Yiddish, and what they read in Hebrew they didn’t understand. It’s not a joke, it’s a real fact. On one side of the synagogue there was the men’s part of the hall, and on the other – the ladies’ part. There were prayers, during which it was necessary to weep. So when these prayers were ending, the men’s part was already making merry, and women, before it got to them, would still cry.

Grandmother Meilakhs was a housewife, she spent all day long by the Russian stove 3: cooked galantines of hot and salty fish, prepared hors-d’oevres for vodka from salty fish or beef legs, sold vodka. Grandmother put on the simplest long clothes. I can remember that usually on the eve of Sabbath, on Friday morning, white bread would be baked for Saturday and Sunday. On Monday rye bread was baked for the whole week.

The house was like this: a large room, where vodka was sold, a small bedroom, a small kitchen, behind which there was a large room, where visitors spent the night, because the house also served as an inn, and the countrymen led their horses in the big courtyard, and slept on the straw. Four rooms without cellars. Earth floor. Furniture – tables and benches – was made by the local joiners. There was no water supply or electricity. In the settlement there was a water-carrier, and he brought water. The house was heated by firewood. Firewood was bought at the market. There was neither garden nor animals, because houses were built very close to each other and there was no free space. There were no maids or assistants either.

When and where my maternal grandfather Peisakh was born, I don’t know. He died in the settlement of China-Town in Vinnitsy district, in the 1920s. He didn’t receive any education, except for сheder. He never attended a yeshivah. Yeshivah gave you a professional schooling, they taught boys who prepared to be rabbis. His level of religiosity was very high. He prayed every day. I remember, how I stayed at his place as a boy of eight or ten, on a visit. I remember how traditions were observed. His business was to make and sell wine made of raisins. He sold it by wineglasses, he didn’t sell by bottles. Wine was consumed right there, on the spot. Countrymen didn’t like to take wine home, because their wives could beat them for drunkenness. There is no information about his brothers or sisters. He had hardly served in any army. Peisakh’s mother tongue was only Yiddish.

My maternal grandmother Dvoira died in the 1920s, in the settlement of China-Town. She was buried there. Where she was born, I don’t know. It is only known that she lived to be over eighty years old. It means that she was born in the 1840s. Grandmother Dvoira received a home education. The level of her religiosity was high. She knew all prayers and regularly prayed, and she could read Hebrew. She helped my grandfather, her husband, and was engaged in housework. Her mother tongue was only Yiddish. I have nothing to say about her brothers or sisters.

Life of Jews in Russia

Their house survived, there were no pogroms in the area. The local peasants understood that Jews brought them profit, because the Jewish settlement provided the villagers with craftsmen. In the Ukrainian villages there were no smiths, or coopers, or shoemakers, or tailors. All these services were provided by the settlement. Therefore they understood the advantage of the existence of the Jewish population. And Stolypin 4 reported to the Tsar that in areas of Jewish settlement local peasants lived better than in those places, where there were no Jews. Because, as he explained, Jewish settlements gave them the handicraftsmen, and bought natural products from them. The Jews didn’t keep cows, sheep, or kitchen gardens, they bought all of these. So they provided both the demand for food products and the supply of labor.

That is why Stolypin reported the situation to Nikolai II and suggested, ‘It is necessary to cancel the settlement boundaries for Jews 5, because in settlements there is an abundance of shoemakers who need jobs, they have nothing to do, whereas outside settlement limits there is hardly anybody to repair your boots.’ The Tsar answered, ‘I agree with you, but my heart does not allow me to do so. And my heart never deceives me.’ [Editor’s note: In December 1906 P. A. Stolypin signed a government decree on partial withdrawal of legal limitations for Jews, directed at the achievement of complete equality in future. However, Nikolai II answered: ‘In spite of really convincing arguments for such an enterprise, my inner voice keeps telling me not to assume the responsibility for this decision’ (Correspondence between N. A. Romanov and P. A. Stolypin. The Red Archive, v.5. Moscow, 1924, page 105).]

Everyone in the settlement was very closely connected to each other. Some distinction was only between the handicraftsmen and the traders. The handicraftsmen concluded marriages between themselves, traders between traders. Trade dealers in our settlement lived in the center, and handicraftsmen lived on the outskirts. Why on the outskirts – because clients came to them from villages. With their craft they served five neighboring villages in a radius of three-five kilometers. And consequently it was better for them to live on the outskirts.

It means that the government had already selected our district as an official Jewish settlement. One or two Jews lived in each village before the revolution 6. As a rule, they were small traders. A trader rented a house and kept salt, sugar or kerosene for sale in one room – all the most necessary things for the villagers. The dealers felt themselves in a completely special position. And on holidays, on Rosh Hashanah, on Pesach they came to the settlement. And I don’t remember that before the revolution there was any fear. Everything was completely quiet. When the revolution began, all of them fled from their villages at once, though nobody had touched them by then.

The typical occupations of the Jews in that area were commerce and craft. Dealers made up to 30 percent of settlement’s population, handicraftsmen – 40 percent: smiths, shoemakers, tailors. Craftsmen made carts, coopers made barrels. And they serviced five villages. And peasants themselves had no time to do all this work. But they sold their produce in the settlement’s market place. When Stolypin reported to Nikolai II, he underlined, that in Jewish settlement areas peasants always paid taxes in time. And outside of settlement limits there were tax shortages, because countrymen had no one to sell their produce to.

Once a week a trade fair was held in the settlement and peasants from the neighboring villages arrived. On such days my father used to put up a tent in the market place, and in this tent he and Mom sold ready-to-wear clothes, which they sewed. They bargained and they ‘shook hands.’ There were many other Jewish tents. And it was only Jews who sold clothes. A little bit aside was another market, where peasants sold meat. Meat was sold only by villagers. Jews didn’t show up there at all. And further away there was a ‘torgovitsa’, a market place in Ukrainian. There they sold cattle and horses. In that market Jews actively participated. There were Jews, who bought cattle for slaughtering, and Jews, who bought horses and then resold them. The Jews bought only kosher meat.

The population of the settlement amounted to a little bit over one thousand men; there were five streets. One-storied houses from east to west, unpaved streets. No conveniences in the houses. No electricity or water supply. In each house there were kerosene lamps for illumination. Toilets didn’t exist. It was everyone’s own business. You could seldom see real floors in a house, usually they were just earthen floors. We had a wooden floor in our house. Furniture: table and stools. And only our family as a relatively well-to-do one had some chairs.

People lived very modestly, without pretensions. Everyone was happy, if he wasn’t hungry, had some clothes and footwear. A suit sewed for a wedding was kept almost to the man’s last day. It would be put on only on holidays. But cleanliness was strictly observed. By the way, an untidy Russian woman was called a ‘slut,’ and an uncleanly Jewish girl was called a ‘shtinka’, stinker. Each house consisted of two-three rooms, and some houses didn’t even have separate bedrooms, because owners couldn’t afford it. There were no two-storied houses. The first two-storied house I’ve ever seen was when we moved to another settlement. Anyway, our house differed very little from those of peasants.

There were three synagogues in the settlement. There was an old bet midrash [synagogue and study house], there was a newly constructed synagogue and a small synagogue for the handicraftsmen. The handicraftsmen went to their synagogue separately from others. This was a tradition. There was a rabbi in the settlement, a very respectable and honest man called Berkhard Berezhansky. The rabbi was above medium height, broad-shouldered, with a thick beard and gentle face, very kind and clever. Many residents of the settlement would seek his advice. He was our neighbor. But it was impossible to live on the income of a rabbi, and his wife was engaged in commerce.

When the rabbi was invited to my sister’s wedding in 1925, he raised a toast and said: ‘Long live the Soviet Power, otherwise how would I be invited to such a great wedding, if not for this power!’ He was a joker and a plain, easy-going person. One of his sons, when religion was subjected to persecutions 7, started to work as a shoemaker with me, as a cutter. He worked as a cutter, joined the Komsomol 8 and then entered a military academy. He reached the rank of lieutenant and was killed in Stalingrad 9. He left for a reconnaissance mission and never came back.

There also was a cantor in the community. A cantor is a singer performing prayers. There was a column in the synagogue, behind which he prayed. And the chorus would sing, repeating after him. He was a self-taught man.

There was a mikveh in the bathhouse, a pool for ritual ablutions. After washing yourself in a bath, you would descend several steps, dip into the water a couple of times and get out. There was a well nearby, and the bathhouse attendant would start bringing water to fill the pool from early in the morning. According to the Jewish law the water must be flowing, but it was impossible. I can remember it very well, because I used to bathe there often, every week on Fridays with my father; we would plunge in and jump out. But everyone was healthy. From the point of view of the Jewish law, the rabbis believed that such a mikveh was better than none.

My parents

My father’s name was Avrum Gershevich Meilakhs. He was born in the settlement of Tyrlitsa, Monastyrischi district, Lipovetski region of Kiev province in 1876. He studied in a сheder, and could write neither Russian, nor Ukrainian, only Yiddish and Hebrew. But he knew the Torah by heart. He was an Orthodox Jew. He observed the kashrut, absolutely all holidays and prayers. Father served in the imperial army between 1897 and 1901. And the commander of their regiment was very insistent in persuading him to get christened. Father was a very good soldier, first in all affairs, and he had constantly heard: ‘Get christened, we will teach you, we will help you’ 10. My parents used to read the prayer ‘Shma’ every day [Shma – a famous everyday Jewish prayer]. Mom and Dad would pray and I would repeat after them. So by the time I learned to speak, at about three-four years of age, I learned to pray as well.

From 14 years of age Father worked as a sales assistant in a shop of a rich Jew. Later my father became a tailor, and was engaged in small trade, and Mom helped him. Daddy worked as a sales assistant for my mother’s uncle, a very well known man called Neller Shlay. Obviously, it is through him that they got acquainted. They got married in a synagogue. Civil marriages were very much condemned at the time. They got married in a synagogue, in accordance with all customs, everything was done as necessary. Their marriage was registered in 1903 in the settlement of Tyrlitsa, and in 1904 my sister was born.

My father was the village headman. All the provisions for the poor, all donations and mutual aid went through him. On Friday morning bread for Saturday was baked in each Jewish family. And each family baked a small bun for paupers. And my granny would send her elder grandson to collect them. When I grew up and was about eight years old, we used to wander with a basket around the settlement from house to house, and the folks gave us those buns. We brought them to Grandmother, from one street, from another, from the third, and then she arranged, who of the beggars the buns should be taken to. And thus, from my childhood I’ve seen enough of the real beggars. Usually they were sick people. In the synagogue you could also meet poor men, but not from the nearby settlements. The beggars would leave their native places not to dishonor their relatives. In the synagogue on Friday night there also were about eight to ten beggars. It was seen to it that each well-off Jew would take a beggar to his home for Friday and Saturday. And in our house, as a rule, there always was a poor man sitting at the table with us on Friday. I saw many of them in our house.

Father was evacuated to Alma-Ata [today Almaty in Kazakhstan] during the war 11. After the war he didn’t get any pension, I supported him. My wife went to see him every seven months and brought him the money. It was impossible to transfer money then. When she visited him, she washed his clothes and helped him about the house. And then she would put the money in his bank account.

During the Holocaust, Mom was evacuated to Alma-Ata too. There she died. Mom had three cousins. One of them was executed with his family by the Germans, shot in 1942 in the settlement of Dashev. I went there to see the mass grave. He lived in the settlement of China-Town where my mother was born. He was also engaged in winemaking: he bought raisins and made wine.

My mother, Neila Skhovof Isaakоvna, was born in 1878 in the settlement of China-Town in Vinnitsa province. What the origin of this name is, I have no idea. It is about 12 kilometers away from Vinnitsa. And she died in Kazakhstan, in Alma-Ata, one year after Father’s death in 1971. She received a home education. Anyway, I remember her sitting and tracing words with her finger in some fairy tales, however, not Jewish ones, but I can’t remember what language it was. And she knew the Jewish language; she read prayers freely. The level of her religiosity was extremely high. She prayed all her life. She knew prayers by heart, and she observed all holidays. She was a very strong believer. And she helped the poor very much. Our family believed that help to the poor was a serious God-pleasing deed. Her mother tongue was Yiddish. She helped my Father in sewing and trade. She went around market places. My mother spoke Yiddish and poor Ukrainian. It was necessary to communicate with the buyers. So Mom learned to read Russian by herself.

On Friday we baked white bread for Friday, Saturday and Sunday. And at the same time we baked a small bun for the poor. On Monday we baked rye bread for all the week. Meat was bought at the market. We bought live hens from peasants, who brought them out for sale in the morning. These hens were cut by the shochet, following all the tricks of the trade, with a prayer, as it was necessary. I carried these hens to the butcher and I remember how he did it and how he said a prayer.

My parents had enough food to eat and enough clothes to put on and were very happy with their life. They never aspired to richness. It wasn’t even discussed. Our house was one of the best in the settlement. Father built it himself. He employed workers to help. A small living room of about three by four meters, a small dining room and a kitchen. Between the living room and the dining room there was a wall with a stove, heated by firewood. And a similar wall separated the bedroom with two wooden beds made by the local joiners. There they slept. The furniture was all made by the local Jewish joiners. Only a couple of chairs had been brought by Father from somewhere else. A big table separated the kitchen and the workshop, where there were three sewing machines. Father would cut, and Mom would sew, and later they hired two Jewish girls, who helped them. And they used to sell their produce. Besides, there was a small store in the same house. And when it was raining and you couldn’t go out, they sold ready-to-wear clothes to peasants in this store.

My father’s elder brother Gershim was three to four years older than him. He died approximately in 1928. He was a beer seller. More precisely, he didn’t sell, his wife did, and he prayed and helped her. She was a very dashing woman. They had a horse, and they delivered beer to villages. They lived in the settlement of Tyrlitsa.

His second brother Motel lived in the city of Lipovets, Kiev province. He was born in 1874, and died in 1919. He was killed by gangsters in the forest, where he worked. He was an expert in wood matters.

Father’s third brother, Akiva, was born in the town of Tyrlitsa. He left for America in 1901. When the war came to an end, he tried to find my father and sent us his address. But at that time I studied in the institute, and any links with foreigners were dangerous 12. Father didn’t reply. Now it is safe. Quite recently, about a year ago, I had a chance to help people from America find their relatives in Russia.

Mom’s elder brother, Nukhom, after being dispossessed, escaped to Odessa and lived there. He was a sales representative. He went through settlements and sold gold things, basically, as an intermediary. The second brother Akiva was religious. He was an accountant in fish farms in Astrakhan. He was killed by Budenny soldiers in 1920. S. M. Budenny was a well-known commander of cavalry troops in the Red Army. Two soldiers came to his house, drunk, he came out to meet them and got killed.

Childhood and youth

I was born on 25th June 1909 in the village Tyrlitsa, Monastyrischi district, Lipovetski region, Kiev province. My mother spent her time going through market places with Father. I had a nurse, Marika, her surname was Kolmiychuk, an Ukrainian girl, who, as I was told, cared very much about me. When pogroms began, I was nine to ten years old and I lived with her. She cared about me so much that she remained in my memory as a close relative. She died during the famine 13. If I hadn’t been so small then, I would have taken all the possible care of this girl, who was so good to me, who actually had brought me up. I would have done my best to save her. Caring for a fellow-human, helping a human is the right of the human soul. And I take pride and pleasure in recollecting that the Ten Commandments were the program of life for my parents.

We had a Derek-сheder for junior students, who were only taught the Torah, and a Gemara-сheder for the seniors, after three years of studies. The Derek-сheder occupied a small room. All teachers were men with full beards, wearing kippot. All boys wore caps. All of us went to the сheder by five or six o’clock in the morning and were released for lunch at eleven-twelve. The school was not far from our homes. An assistant, we called him ‘beelfe,’ would take us home and back. I started to attend сheder at the age of five. I learned the alphabet from the Torah. From the first day I would sit down at a table, open the Torah, and study the letters. The Torah has 52 chapters, and each week we studied one of them. The following year we went through the same chapters with comments of Rashi 14. Each year we studied the Torah: In the first year with one kind of comments, in the second year with another.

Then I passed on to Gemara-cheder. In the сheder for older children they studied the Talmud. [Gemara, a part of Talmud embracing the latest and detailed interpretations of principal laws of Talmud, Mishnah.] That school was located in a small room, which you entered through the kitchen without doors. There was a rough wooden table. Ten boys sat at this table with Talmuds, and the rabbi sat at the head of the table. We read and translated classical Jewish texts. That’s all we did. There were no breaks. If one needed to go to the toilet, he was let out in the street. There were no toilets in the settlement, so we did what we had to directly on the ground.

You know what I’ll tell you – cheder was a very useful institution not only in the sense of education and studying the Torah, but it helped developing abstract thinking in kids: when children of seven years of age were already thinking about the creation of the world and about God. And the settlement limits, devised especially for Jews, resulted in the appearance of real geniuses! Because people living within these settlement limits couldn’t even dream of acquiring the positions of city executives, of power and riches, they could only think of spiritual life.

In 1918 сheders were closed. The authorities would punish people for illegal teaching and studying the Torah. I went to an elementary school. My first teacher was Vasily Andreevich Meschik, a Ukrainian. In our settlement there were only four grades of elementary school. And then Father took me to another settlement of Dashev, not far from Tyrlitsa. I lived at my uncle’s home and went to school there. It was a seven-year school. There were only Ukrainians there. They liked to stress then, that they were Ukrainians, not Russians. I remember all of them with a warm feeling, especially Maria Sidorovna Samarina, the teacher of Botany. She was very kind and tender. The school was outside of the settlement, one or two kilometers away. And the teacher lived in the settlement too. We watched out for her, boys and girls, when she would leave for school, and joined her. And on the way she would tell us interesting stories, and we would confide our secrets to her as well.

There’s something else I would like to tell you about her. Daddy paid for the first year of my study. Elementary school was free-of-charge, and the seven-year school was to be paid for. So he came twice a year, bought a sack of wheat or rye at the market and took it to the school as a payment. And when I passed over to the sixth grade, my marks were like this: satisfactory, unsatisfactory, and then two goods. I studied rather well and the director called me up and said: tell your daddy not to buy grain any more, we will teach you free-of-charge for your good results. And once we had my uncle visiting, my mother’s brother, and Daddy told him in confidence, so that I wouldn’t hear, that when asked about my progress Maria Sidorovna told him, ‘He will be a professor.’ I overheard that, but I wasn’t especially interested in such things then, I just didn’t know what it meant. Now I am grateful to my destiny that I became a professor at the university and wrote three dissertations.

Absolutely all Jewish traditions were observed in our family. On Sukkot we used to put up a special tent [sukkah]. We sat in this tent in the open air. If you pulled the cords, the roof would open. We ate in this tent. And we celebrated all holidays. Pesach was a special holiday. I went to the synagogue with my father and prayed with him. When the сheder was prohibited, I took Talmud lessons with one almost completely blind Jew. It was done illegally. I couldn’t help admiring this blind Jew in his poor house. As soon as I finished reading a line from the Talmud, he continued citing to the end of the chapter by heart.

Our parents didn’t teach us anything; they were illiterate. Customs had educational influence upon us by themselves. We strictly observed all the traditions, kosher principles and holidays. I can see now: on Saturday Father and I are walking to the synagogue. I have a prayer book in my hand. Father tells me, what I should do. I am 13. Father invited a famous rabbi from Monastyrische, and he carried out the bar mitzvah.

Probably our favorite holiday was Lag ba-Omer, the 33rd day after Pesach. [This day is known as a student’s holiday. Kids in cheders and yeshivahs are released of studies and allowed to play various games.] A sunny day and we, the boys, were in the street. For some reason we were playing with hoops. All this is clearly imprinted in my memory. I also remember how after Yom Kippur we went down to the river, and everyone shook out the contents of their pockets. It symbolized shaking away our sins. It stuck in my memory how the peasants from the neighboring houses jumped out and watched with great respect how Jews were observing the precepts of their God.

I began to give private lessons when I studied in the fifth grade. Neighbors’ kids were in their first and second grades. The requirements then were very serious, no indulgences, only hard work. Our neighbors asked me to practice some Arithmetic with their children. So as early as at the age of 14 years I became a teacher. I had tutors as well. When I was transferred to the seven-year school, to the fifth grade, I was good at arithmetic. But I was one month late for the beginning of the academic year. They were already studying algebra and I didn’t know algebra. So Father agreed with one Jewish student – a student was regarded as an academician in the settlement – and he taught me algebra for one month, until I achieved the required level. Judging from his looks, he wasn’t religious, without a beard. But, most importantly, he wore a student’s uniform and a cap, and was a real student.

My closest friend was Misha Moldavsky. He was from an assimilated family, not religious. My parents didn’t know about it, only my uncle knew. But this family was well educated, and their mother was educated, they were all literate. It was generally appreciated, therefore my uncle didn’t criticize our friendship. The Moldavsky family owned a small factory with 25 workers, an iron foundry. Once Misha invited me to spend the night at his, and his mother invited me to dinner. I was sitting at the table and suddenly I saw a piece of bacon in my borsch [red-beet soup]. I was so terrified. I knew that I was committing a sin, but how could I refuse? And it was my first violation, in the sixth grade. I ate that piece of bacon. I had a strong feeling of guilt for a long time after.

Then I joined the organization of pioneers 15. You know, it was an anti-religious propaganda, carried out by absolutely illiterate people. There was a close ally of Stalin – Emelian Yaroslavsky. His real name was Gubelman. He was the author of a brochure dedicated to the Bible. I read it when I grew up. It was a criminal explanation of the Jewish legends in the literal sense of the word. The Jewish legends, all these records, have a historical value. He didn’t acknowledge even that. And religion, as a matter of fact, had been ousted by force, rather than by propaganda. We were forced to sing such a song. It is a shame to cite it here, but for you to have a better idea about that time [1922], let me quote two lines [the interviewee sings in Russian]:

‘Down with all the monks, rabbis and priests

We’ll climb upon the skies, and we’ll disperse all gods’

Teachers, who we loved and appreciated, stood aside from all this disgrace. Later pioneer leaders appeared at schools, mostly illiterate workers. So these uneducated workers, who came to school to create pioneer organizations, snatched out the best schoolchildren and made them pioneers. With time they made every pupil a pioneer… But I continued to pray up to my seventh year in school. I didn’t turn on the light on Sabbath. I stood at the window. I knew prayers by heart. But it was necessary to hold the prayer book. I would stand at the window, holding the prayer book, and our boys and girls passed by along the street from school and saw me in my vestments. Nobody ever teased me. So all this godlessness was superficial, imposed upon kids by force.

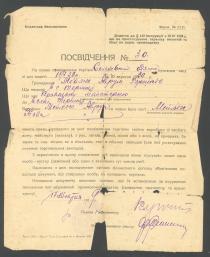

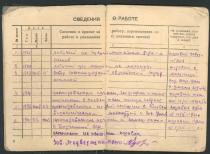

Up to the age of 13 I lived in the family of my parents. Later I moved to my uncle in Dashev. In 1925 I finished a Ukrainian national school simultaneously working as a laborer at a mechanical plant in order to earn my food. In 1926 I moved to my other uncle in the village of Kalnik three kilometers from Dashev, and worked at a mill – chopping firewood and helping around. From that time my official work experience is registered in my documents. Usually after dinner, it was customary in the settlement to have a nap. Frequently we went for a visit to our relatives and friends. In religious families it was very common to read Kohelet, and I remember, that the book was commonly cited in everyday life. When I turned 13, a rabbi arrived and performed a bar mitzvah for me. I regularly prayed until I turned 15. Later religion was so much persecuted that it became simply dangerous to exercise religious ceremonies.

I never felt any anti-Semitism from the part of teachers or classmates in my whole life. On the contrary, Russians would always treat me very well and even helped me. I checked myself many times on this matter, but no, I’m convinced there wasn’t anything, neither from teachers, nor from students. Why didn’t I experience anti-Semitism in the course of pogroms? Peasants protected us. We had no pogroms, because the priest and the peasants, the parishioners, interceded for us. And at the time of Demidov pogroms, the attacks of Demidov’s gang, Jewish girls used to hide in the priest’s house. Because the gangsters raped the girls, who failed to hide in time.

I remember well the first raid of Volynet’s gang [1918]. My cousin grabbed my hand and dragged me through kitchen gardens to the peasants, where we were given shelter and were fed until the end of the day. The neighbor of the owner came and told him, that the gangsters were riding through the village, shouting: ‘Drive out the Jews, or we will shoot the owner!’ And the landlady, Taraska Kudina, took me from the stove and, calming me down, lead me to the ‘klunya’ and hid me behind the sheaves. A ‘klunya’ is a shed, where they stock sheaves. She left me there and came every half an hour to remind me that I should sit quietly. In a couple of hours she came back and said that the gang had left, and led me to my parents. I also remember a raid of Denikin 16 bandits. All the girls hid in villagers’ houses, and the majority of them ran to the house of our priest, Nikolai Ivanovich Kopeiko. And he gave them shelter and food until the gangsters left.

‘АRА’ stands for ‘American Relief Administration’ 17, an American organization, which helped Jews, victims of pogroms, in the 1920s. They brought food stuff – condensed milk, cabbage, oil – as well as clothes to villages where massacres took place. And those who suffered from pogroms were asked to describe in written form what happened and these records were kept as archives. I worked on ‘АRА’ archives, when I was a post-graduate student. For each document we filed a small card. I remember a description of a terrible massacre. Over one hundred men were executed. And those who escaped hid in peasants’ houses. I met a peasant, who had his house as well as his barn full of Jews at the time of the pogrom. So the local peasants not only didn’t quarrel with, but also tried to rescue Jews.

In 1934 I was a post-graduate student of the Kiev University. We were sent to the Kiev State Archive with a mission to study ‘АRА’ archives in two months. Liberberg was the director of the Jewish Institute. He was shot in times of repressions. I was his assistant. He helped us to get access to those secret materials. When we came, the head of the archive, Shkarovskaya, a Jew, handed us ten huge folders, containing all those ‘ARA’ documents. When help was brought to homes, ten ‘ARA’ representatives would come to families and ask every member to describe personally in his own handwriting what they saw during pogroms, all that they witnessed and remembered. We studied each such sheet of paper, described it as it was adopted in libraries and archives, filing a special card for each one. We spent half a year for this business instead of two months. We read and reread all those papers. Where these archives are now – I don’t know. I don’t think anybody has seen them since then.

My two brothers died in infancy, not having lived to one year of age. My sister Peisya-Ita was born in 1904 in the settlement of Tyrlitsa and died in 2000 in Israel, in the city of Rehovot. She was so sturdy that she went swimming on the day of her death. In 1925 she moved to a Jewish agricultural colony in Odessa district. Then in 1932 she moved to join me in Kiev and then in Alma-Ata. Further on, we didn’t have any contacts.

My sister had a son, Mika, born in 1925, who died at the front in 1943 during the crossing of the Dniepr River. She received a pension from Germany, for her killed son. Then I found out from literature that the division, with which he was crossing the Dniepr, was completely destroyed. And I found the burial place. He is buried in a mass grave, where all his comrades, young guys, are lying. I saw the inscriptions on cast iron plates, the majority of the boys were born in 1925. As I found out from literature, three military academies were joined together and they made a combined division. This division was all lost. The cadets had no time to become lieutenants.

I had no friends outside of school. But, there was an exception. Two boys, the Vinokurs, in the neighboring house, didn’t go to school. A poor family, their father was killed by gangsters. Their mother became a widow. They lived in a basement room. I went to see them sometimes. They were two talented boys. One of them could draw very well. In what way their further life worked out, I don’t know. I was friends with them, came to their house, although we didn’t play any games. We only talked. They read a lot. They were literally self-educated boys. And the first Russian novel they gave me to read was a novel by Zagoskin [Mikhail Zagoskin, 1789-1852, a famous Russian writer and historian]. I can’t remember the title. We read, talked, walked. We probably discussed what we read. But most importantly, I perfectly remember, there never was a bad word or abusive language. Recently I passed by a school, and two schoolboys were swearing. It was impossible in our time.

There never were any toys for boys or girls in our families. I didn’t do anything except for reading. For some reason our life was such, that from the first days spiritual things predominated. There was a different attitude to the material values. Certainly, they were appreciated. Everybody needs, say, clothes or footwear. We took care of these, too. I remember only one game we played. When we had a day off, we would collect stones, which were in abundance there, and make a wall out of them. You’d approach at twenty steps, also with a stone, and throw. This was our game.

Another game we played was ‘buttons.’ We played ‘buttons’ in Tyrlitsa. You dig a hole, and throw a button. And it should fall in the hole. If it doesn’t, you are supposed to drive it there with a flick. If you get the button in the hole with the first flick, it stays there. Then another boy throws. From a preset distance, five to six steps. And he, who is the quickest to get his button into the hole, wins and takes all the other buttons. We didn’t know any other games. And in general we were brought up in a serious way. Serious attitude to life. Life is not a game. When you are seven or eight years old, you should prepare for it thoroughly. They didn’t put it in exactly these terms, but in reality it was what they meant.

In Dashev at Misha Moldavansky’s place I learned croquet. That was the first time that I heard of the game. And I also learned checkers. In that settlement people were more competent, there was a hospital and a drugstore. I saw a real Chekist 18 there for the first time. While I am talking to you here, I clearly see the following picture: I’m coming home from school, and there’s an open carriage rushing towards me – a horse cart, pulled by a pair of horses. In this cart sit Yashka Vozhnikovsky and Levkа Felsher, in military overcoats, with revolvers and rifles. They were returning at night from the neighboring village. Two Jews – Chekists. They were looking for someone there. I regarded them at one time with deep condemnation. Now I can’t condemn them, because they joined the ChK to fight against gangsters. It was later that the ChK started to hunt everybody down without distinction.

We were very close with our parents. We frequently sat down at one table, conversing on religious or domestic topics. Since 1924 I stopped visiting my parents, because they were deprived of their electoral rights, and were referred to as ‘lishentsy.’ I could even have been expelled from school for contacts with them. But I knew everything about them and they had news from me. However all this was done secretly.

It is difficult for the new generation to imagine how illiterate Komsomol leaders destroyed families in those years. They broke off the links of kin. Everything that was ‘class-alien’ was eliminated. A ‘lishenets’ meant that my father was deprived of electoral rights because he had been a small trader. There was such an official concept, that traders are parasites. I remember a book that I read. The author was a certain Nikstein, a Jewish surname. Later I found out that he was the son of a Warsaw banker. He had written a book, a brochure, on ‘who is who.’ I read it and learned that a trader was a parasite. And I was supposed to think of my father, who worked twelve hours a day, that he was a social parasite. And he was really deprived of civil rights. I was lucky to obtain a false reference about my social origin. Without this reference I wouldn’t have been admitted in any educational institution.

The first time I rode in an automobile was in Kiev, most likely in 1929. But I remember another fact from before. It was in about 1918. During a lesson the teacher shouts: all out! And we run outside and into the street. It appears that the teacher saw a car from the window: an automobile appeared in our village for the first time. He wanted us to see it. We ran out of the classroom and rushed after that car. The car was an open one. The driver pulled over. We ran around it like wild, until it left the village. I rode a train for the first time in 1918 to the town of Vinnitsa to see the eye doctor. Father noticed that I was shortsighted, and from that time I wore glasses. I always spent vacations in the settlement among my friends.

The first time I went to a restaurant was when both my sons were students. I was walking with them along Nevsky Avenue, and dropped into a restaurant. I had no idea about restaurants before. But I can very well remember the hungry years. It was in the hungry year of 1932. On Sunday the students of the Jewish sector, boys, went to the quay on the Dniepr before six o’clock in the morning and loaded and unloaded steamships, until twelve at night. And for this we were given a loaf of rye bread.

I was a member of the Spartak youth society [1919-1922]. We were the first pioneers, called ‘spartakovtsy.’ I was even elected the chairman of a ‘spartakovtsy’ group. When I turned 16, I was recommended to enter the Komsomol. I didn’t want to. Why? I would have needed to tell everybody about my father – deprived of civil rights – and I didn’t want to tell lies. I thought it was a shame to lie. Well, there was a meeting to decide on who should be recommended to the Komsomol. And I was named. Well, I couldn’t turn it down. But I had a guilty conscience. How should I tell the truth about my father? And I was accepted and sent to the Vinnitsa regional Komsomol Committee for approval, and there the question didn’t even arise. I was the happiest man. God helped me; I didn’t have to deceive anybody.

At school we sang:

‘We will soon set off to fight for the Soviet Power

And we are all ready to die in this struggle!’

We were forced to sing this kind of filth. There were demonstrations in our town on 7th November 19 and 1st May, and at one of the demonstrations I was forced to make a speech and congratulate the participants on behalf of the school. As a student in Kiev I attended all demonstrations, it was obligatory.

My first workplace was at a cast iron factory belonging to a Jew by the name of Scherba. His daughter now lives in Leningrad. I worked for him as a laborer in a foundry shop. I needed work experience to enter a college. The following year I worked at my uncle’s mill, chopping firewood for the machine, and I acquired another year of labor experience. These two years helped me to enter the institute. I had two years of experience as a worker, and another two as a teacher at a Jewish school. Having five years of labor experience, I could enter an institute. And I was adopted with my false reference, which was issued to me by the secretary of the town council, a friend of mine, stating that my father had electoral rights. Without it I wouldn’t have been allowed to take examinations. But I lived in eternal fear that somebody would report on me.

From 1927 to 1929 I was a teacher at a Jewish school. In 1927, when I was 16, I went to the regional center Uman in Ukraine and passed examinations without attending lectures to be a teacher in elementary school. I received the certificate and came to the regional department of national education. I had an interview with the inspector for Jewish schools. This was the time of the revival of national cultures. He advised me to go to Yustingrad, a Jewish settlement not far from Uman, there was a school there. I was surprised that I had never heard about the place before, although I knew the vicinity very well. I found a cart man at the local market place in Uman to give me a ride to the settlement and the cart man first dropped me at a book-store where I bought some school books with the money provided by the inspector.

The place turned out to be even smaller than my native Tyrlitsa. A terrible massacre took place in Yustingrad in 1920, and only those who hid in the neighboring houses of Ukrainian peasants survived. For two years I lived in Yustingrad and shared a rented apartment with a Ukrainian teacher working in the same school. I was paid a good salary for those times, I got over 50 rubles with all bonuses, and I spent only ten rubles for boarding – accommodation and food. Until that time I was poor and miserable, and in Yustingrad I could afford to buy clothes and footwear and even send something to my parents. Later I bought a good suit and a coat and during winter vacations I went to Kiev to see the town and spent a nice time there, walking and sightseeing. I visited my relatives, too.

In 1929 I read in the Jewish newspaper ‘Shtern’ [Star] that a Jewish sector was soon to be opened at Kiev University. And I rushed there at once without any preparations. I passed all exams and was admitted to the Faculty of History and Economics. But I wasn’t qualified for receiving a state grant for the period of studies, because I lacked half a year of working experience. I had only four-and-a-half years, whereas one needed five. To obtain the grant I had to work as a porter at the doors of the university and it helped me very much in my studies – it was an easy job and I could just sit and scrutinize my textbooks in the porter’s room.

This was the first time when I discovered ‘The Capital’ by Karl Marx. Can you imagine what kind of feeling that was? A Jewish boy from a small settlement was for the first time holding the real legendary book by Marx! I was all trembling with agitation. Of course, I read all of it. In 1930 a new method of teaching was introduced in educational institutions – a ‘team and laboratory method.’ Students were divided into groups of four and used to prepare for lectures and examinations together. I was the team leader. We were to report to a professor and the team received marks as one student.

From 1929 to 1933 I was a student of the Jewish sector of Kiev University, the Faculty of History and Economics. There is one sad fact in my biography. When I was a student of the first year of the Jewish sector, the administration organized a meeting concerning the arrest of the ТКP group. ТКP was a peasant labor party, counting the best agricultural experts of Russia – Chayanov, Kondratiev 20 – among its members. Students of Western agricultural colleges still use their books for study.

So the meeting is going on, and professors and students are delivering speeches. And everyone demands execution, of course. I am sitting behind, in fear as always. My reference on social origin is a false one. And I see the secretary of the Communist Party Committee of the university approaching me. I was sure he didn’t know me, but I knew him. The secretary is the second official position after the rector. He comes up to me. ‘You were the teacher of the Jewish school in the settlement of Yustingrad?’ Well, I calmed down a little bit and I said, ‘Yes, I was.’ ‘You spoke at the meeting in the place of the execution of Jews, shot by Sokolov’s gang?’ I replied, ‘Yes, I did.’ ‘I was at that meeting and heard you speak.’ He took me by the hand and said, ‘Let’s go, now you will address the audience and talk against ТКP.’ And I went with him.

First, I feared that somebody would recognize me. Second, I was wondering what I could say about people, who I knew nothing about. He took me to the stage, where I was given a seat in the presidium. I didn’t want to look like a fool. I am thinking: I should say something. And I remembered the stupidest article in ‘Pravda’ newspaper. I read ‘Pravda,’ as I was interested in politics. But only for fear that politics would sometimes take me by surprise. And some bastard wrote in ‘Pravda’ that this peasant labor party came out against industrialization of the country. Ostensibly they proved that Russia could be heated with straw. And I’m losing my conscience. I am in confusion. The floor is given to a student of the first year of the Jewish sector, me. I step forward and I start to explain that the peasant labor party, illiterate, uneducated people, wanted to heat Russia with straw, and I was greeted by applause. I feel shame to this day. If I hadn’t been put in prison, I would have had to appear at such meetings more than once. One could do nothing about that.

After graduation I was recommended to enter the post-graduate courses of the Institute of the Jewish Culture at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. And there I passed candidate’s examinations 21 and wrote a thesis on the history of anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages. This thesis was recommended for defense in March 1936. But on 3rd March I was arrested. I was arrested by two Jews. And I was interrogated by three other Jews. And the reason for my arrest was my thesis. The question of the investigator Borisov – this is a pseudonym – was: ‘Who executed the first Jewish pogroms in the Middle Ages?’ I answered: ‘The crusaders.’ ‘And who were the crusaders?’ I am telling him, ‘Knights and peasants. ‘Oh, peasants? So you are a Trotskist! Lev Trotsky 22 considered peasants to be a reactionary class. You wanted to compromise them here.’

So, the Jewish sector of the university was closed, everyone was put into jail, the Institute of Jewish Culture was shut down. This was the end of Jewish science in Kiev. I spent the years from 1936 to 1941 in Vorkuta. We were making a glade in the woods for the future railroad and I worked in timber cutting. My comrades in the camp were Russians and Tartars and people of other nationalities. We had no national enmity whatsoever.

In exile

In 1937 my father and mother were exiled to Kurgan district, in the village of Chasha, and they remembered all their life, how the local population cared for them. They had no property. Only what was on them. Neighbors brought them a bed, a mattress, someone brought a pillow, another – a few potatoes. My parents remembered these people with big respect and gratitude. Father got a job as a watchman in an agricultural school. Fortunately, after one year the chief of the regional Internal Affairs department came to them and said: ‘You can return to Kiev, you are released from exile.’ Who did it, they didn’t know. They believed that it was the chief’s initiative. He treated them very warmly and attentively. And they returned to Kiev. They were evacuated from Kiev in 1941, when the war began. During the war our settlement Tyrlitsa was completely destroyed. I have been there twice since. There were two houses left. It is hard to think of it. And nobody survived.

From the camp, from Vorkuta, we were allowed to send censored letters every six months, and they performed a very strict accounting of that. I sent a letter every six months. But my parents hadn’t received any letters, and thought that I was dead. I was released from Vorkuta, and that was great luck, because with the beginning of the Finnish war 23 many prisoners wouldn’t be freed at all, and psychologically I was prepared for that. But I was lucky to get my freedom back. It was on 3rd March 1941.

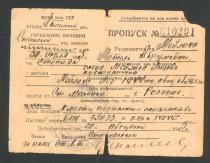

In 1941 I came back to my parents in Tyrlitsa. We were all together exiled to the area of German settlements in Volga region, the village of Gusenbakh. When we came we were allowed to settle in any house! The place was empty, houses open, furniture, home utensils – everything in its place, as if the owners had just come out and would soon be back. Even potatoes remained undug in the kitchen gardens. No people at all except for the exiled like us. All Germans 24 were deported to Kazakhstan by then even without a chance to change clothes. And when the war began in summer 1941, they stopped releasing convicts at once. I returned to Kiev, but I didn’t stay there for long. I had article 39, ‘enemy of the people’ 25, in my passport, saying: ‘Without the right of residence in cities.’

After one year, in 1942, I was arrested again upon the accusation per the same article 39 – ‘enemy of the people’ – and exiled for lifetime to Kazakhstan. My parents remained in the German settlement area of Volga region. As a matter of fact, I had no serious incidents. Even in the prison camp, I enjoyed the warmest attitude from the brigade of porters, which consisted of the dispossessed men. I wouldn’t say that there existed any anti-Jewish, anti-Semitic laws that affected my family and me. The entire official system was such, all of it wasn’t very friendly. We tried to think about it as little as possible. Each of us did our own business, that’s all.

I found myself in the town of Akmolinsk in Kazakhstan for ‘lifetime settlement.’ I wanted to work. I found the regional department of people’s education and tried to find a job there. OBLONO [the regional department of national education] gave me an assignment to Stepnyak. An inspector filled in an assignment for me and I bought a ticket and reached Stepnyak. I didn’t want to work in a school. I didn’t even think of school at all, but if you weren’t going on business you weren’t given railway tickets, and I wanted to leave Akmolinsk as soon as possible. I worried about the possibility of being arrested again. I was scared to start teaching at school! I got used to cutting timber in the woods and working as a loader in the camp. I was very nervous.

In Stepnyak I went to work as a day laborer, in the direct sense of the word, to one party boss. I dug the kitchen garden for him, and chopped firewood, and brought water, and cleaned the toilet. Everybody called me ‘Dekhterenko’s hand.’ He gave me a room, not heated in winter, and a large sack of hay, on which I slept, and an old sheepskin coat, with which I covered myself. I lived in his house for one year. After I got married, we were given a separate room. Other teachers knew that I was exiled, but treated me very warmly, with much sympathy. And I am grateful to them all until today.

From 1942 to 1945 I taught German language in the Stepnyak school, at the same time working as a porter to stay physically fit. In 1942 I got acquainted with my future spouse at school. Lyuba, my future wife, was standing at a school window, that’s how I first saw her. It was love at first sight. Before the war I never thought of getting married, because I was fully occupied with my candidate’s thesis and started to work for a Doctor’s degree. I had already prepared my doctoral thesis, too, with all the materials on the topic ‘Entry of Italy into the First World War.’ The Jewish theme had already lost its urgency by then. You could feel friendship between individuals, not so much friendship between the peoples, however. But it seemed that the issue of anti-Semitism was losing its topicality.

I got married in 1943. My spouse’s name is Lyubov Kuzminichna Kirichenko, she was Russian. She was born in the village of Borovoye in 1918. Her father Kuzma Leontyevich Kirichenko was deprived of his property by the Soviets, and her family kept moving from place to place, afraid of the possible arrest of her father. Lyubov finished ten grades of secondary school, but in different schools for that reason. She finished school in Stepnyak in 1936 and that same year went to Moscow and entered the Physics Faculty of the Moscow Teachers College. She graduated from the institute in 1941. From 1940 to 1943 she worked as a teacher of Physics in different schools.

In our family we didn’t celebrate religious holidays. The father of my wife was an atheist. At first we lived with my wife’s father and later, starting from 1946, with my parents. I am happy to recollect how kind my wife was to my parents. And they literally adored her. In the synagogue father called her ‘tsadekes,’ ‘saint’ in Yiddish, when asked how he was getting on with his Russian daughter-in-law.

In Stepnyak I was friends with Kazakhs, Russians, Ukrainians and Germans, who were deported there. There was a Jewish family of the director of the Mechanical Factory. Certainly, I didn’t try to get acquainted with or visit him. He could be compromised by such an acquaintance. He was a good man, and he was also arrested during the so-called Doctors’ Plot 26 investigation. But he was quickly released, because workers respected him a great deal. When he was arrested, the workers, about 100 of them, tried to defend him as much as they could. And they succeeded. After the war I was on very good terms with the inhabitants of Stepnyak. And when we were leaving, they went out to see us off and were very sorry that we were moving away, and we were sorry, too. The attitude towards us was most friendly. I remember with gratitude the Russians, Ukrainians and Kazakhs.

In Rossosh I worked from 1945 until 1949. I lectured on the history of the Ancient World and Middle Ages at the Teachers Institute. It was there that I defended my doctor’s thesis ‘Entry of Italy into the First World War.’ In 1949 a commission from the regional party committee arrived and they attended my lectures together with the pro-rector Efremov, a remarkable man. After lectures they told Efremov that they were very pleased with my lectures. And at a meeting in the institute they declared that I advocated cosmopolitan ideas 27 at my lectures, and demanded that I be dismissed. Nobody of the institute’s staff supported them. I decided to resign in order not to let anybody down, and return to Stepnyak.

At night two militiamen took me to the state security building, the KGB 28, where I was interrogated, and during the interrogation a guard comes in and says, ‘There are some people there that want to talk to you.’ The guard remained with me, and the chief of the KGB went out to these people. He returned in ten minutes and asked, ‘What shall I do with you?’ I was surprised to hear such a question and said, ‘Give me an opportunity to take my family, my wife and two small children to her parents.’ He answered, ‘I’ll do that, but you promise to leave in the morning!’ It turned out, those were my students who came and asked not to let me go away…. But he released me, and I left that very day. It was the only time when I was persecuted and dismissed as a cosmopolitan. I never had any conflicts whatsoever for being a Jew.

My elder son Lev was born in Stepnyak in 1944. My second son Alexander, Sasha, was born in Rossosh in 1947. Lyuba, my wife, went to work in a school as soon as our children got older. During my whole life I had a rather modest income, so we lived very modestly but amicably. I have two children and a granddaughter, who is a non-believer, an atheist. From the first days of my sons’ conscious life my children knew that I was a Jew, and knew that I suffered from persecution. I tried as much as possible to tell them not only about my life, but also about the society, in which we lived.

Jewish culture is very close to them. They felt their Jewishness right after graduation from the institute. They couldn’t get a job. My younger son Sasha, having a diploma with only excellent marks, except for the History of the Communist Party, and being already an author of his first printed works, couldn’t find a job. He was unemployed for almost a year. All this is described in his novel ‘Confession of a Jew.’ My children very deeply felt and realized that their numerous problems with various officials were caused by their being Jewish. And I was working as a teacher by that time. I was not so much susceptible to such problems.

I remember one interesting fact. A personnel manager once came from the famous Arzamas-16, where they were working on atomic bombs. Her mission was to select the two best students of Leningrad University to work in Arzamas-16. They were asked to arrive at a certain place with their suitcases packed. When the guys arrived, my son was rejected. At the last minute they found out that his father was Jewish, moreover – a person subjected to repressions, and my son wasn’t hired. After that he had no occupation for half a year.

Both my sons had problems entering colleges, Lev less so, but Sasha had quite a hard time with that. In Stepnyak my elder son Lev had a friend, a Tartar. He went to Leningrad one year earlier than Lev and entered the university. Lev came to Leningrad in 1960 and passed examinations, too, but wasn’t admitted. But he applied to the Polytechnic Institute at once and successfully graduated from it. My younger son Sasha went to Moscow in 1965 to enter the Moscow State University, passed all examinations with best marks, but failed to find his name in the list of the admitted. Then he went to Leningrad to join Lev, and passed examinations to the Leningrad State University, the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics. Thus both my sons are mathematicians.

After rehabilitation 29, which was delayed three times, I worked, enjoying respect from colleagues and friends, until 1969, when I retired. I was refused rehabilitation three times because when they first arrested me I hadn’t signed any papers slandering anybody. They remembered that, and were now taking their revenge on me. In Belaya Tserkov [1958] I rented an apartment from one Jewish family, but didn’t stay there for long. After rehabilitation I had a right to return to Kiev and receive an apartment. But I didn’t do it. It is difficult to say why. I decided to remain in Kazakhstan and I moved to the city of Kustanai, to the Pedagogical Institute, where I taught History of the Ancient World. There was a good group of professors there, and I felt fine there and worked until my pension age.

Life under the communist regime

I believed in Marxism-Leninism, as in my childhood I believed in the Torah. I never trusted Stalin. The matter is, that I read a lot of old literature and knew, that Stalin was a worthless man, an adventurer. Besides, in the camp I frequently met an old Trotskist named Verap, mentioned by Solzhenitsyn 30 in ‘Gulag.’ In his time he gave a recommendation to join the Communist Party to such a major political figure as Beriya 31. Verap received 400 grams of bread in the camp, and I, as a porter, earned sometimes more than one kilo. He told me a lot of secret party intrigues. His stories about Stalin had fully convinced me that the man was a dull-witted political adventurer, an intriguer.

Besides, I used to read books known to few people nowadays. There was, for example, a brochure by Trotsky ‘The Lessons of October.’ In this brochure he reproaches Kamenev 32 and Zinoviev 33 for voting against the October revolution. Angered, they later helped Stalin to dismiss Trotsky. Then, when they began to criticize Stalin, the latter was supported by Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky. Stalin managed simply to push away the shortsighted people. I knew about it very well from books that I read. Later, when I was rehabilitated, I went to Leningrad. I found minutes of party sessions in a library. They, too, helped me to clear up the situation of those times. I have written several articles based on these minutes.

I had never felt a bad attitude towards myself. At that time I lived in Kiev. In 1949 I was approached by an executive of the town party committee, Stanislav Grigorievich Ekimov, who confidentially warned me: ‘You will be dismissed from your job at school, let’s go with me. I will work as a secretary of the regional party committee in a village, 70 kilometers from here. I’ll give you a job in a school there.’

I went with him and we agreed that I would move to that village with my family. I was promised an apartment. The director of that school appeared to be a Jew. I asked him, ‘We have two small children, is there a doctor in this village?’ He answered, ‘We have not only a doctor, we have a professor of medicine! I mean a Jew from Hungary, who survived during Hitler’s occupation. He was hidden by the local doctors. Our Soviet troops arrested him and sent him to this village.’

But when I returned to get prepared for the move, my wife’s father advised us against it. He said, ‘If they decide to put you in jail, they will find you in any god-forsaken hole. Stay here. If you are arrested, Lyuba will remain with the children and with me.’ I stayed where I was, and I taught German and English languages in a school.

Once the head of regional department of education Iskakov came to our school and said that in the party meeting the chief of state security, Kosyanchuk, noted that I, ‘the blatant trotskist,’ was entrusted to teach party sciences: Geography – I taught it in the fifth grade – and Psychology! After that I refused to teach Psychology, though the director insisted that I continue. I proceeded to teach only foreign languages. Such was my persecution…

I continued to lecture at a free-of-charge optional course on pedagogical ethics. In 1982 we came across a possibility of changing our apartment for one in Vsevolozhsk. We wanted to be closer to our kids. So we changed our two rooms in Kustanai for one in Vsevolozhsk – in a communal apartment 34. We lived there until 1992, and then we moved to St. Petersburg.

After the war I didn’t go to the synagogue and didn’t celebrate holidays, however, I educated my sons on traditions, and how holidays were celebrated before. They know about my parents very well and remember them with respect. When we lived with my parents in Kazakhstan between 1946 and 1949, they observed all Jewish holidays. My kids saw all this and they liked it.

The happiest day in my life was a day in 1949, at the beginning of April. My family and I got off the train at the station of Makinka. Earlier, the rector of my institute told my wife, when she was receiving labor cards, ‘Your husband will be arrested on the way. What will you do with your two children? You can continue your work in the faculty, and I shall arrange for your children to be admitted to the kindergarten, please stay!’ But she wouldn’t even hear of that. ‘Well, then, remember that he will surely be arrested on the way! …’ he told her. All through the journey we feared that I would be arrested, but we reached our destination safely. I came out, the sun was shining. My God, how happy I was! Now, I was thinking, you can arrest me whenever you want. My wife will be already in the family of my father, who won’t abandon her. Our elder son was four years old, the younger one was one year old then.

The death of Stalin in 1953 was a celebration for me. My wife was forced to stand as a guard of honor near his portrait, and I passed by her smiling secretly and rejoicing, because her family suffered from Stalinist repressions as well.

Approximately half of my friends were Jews. My closest friends were Moisha Shapiro and Moidansky, the two authors of the Jewish dictionary. They are my most valued friends. In Kiev I hardly had any other friends, except for a few in the Jewish post-graduate courses. And I should tell you that in the Jewish sector of the Kiev University and in the Institute of the Jewish Culture we had the warmest, friendly relations.

After a while the dictatorship had weakened, it was indisputable. This showed in radio and television programs and in the press. At last I was able to receive books in the library, which they wouldn’t give me earlier. For years I was trying to obtain a book by Professor Shtif, who taught Hebrew in the Jewish sector. And I couldn’t get it. They refused under all kinds of pretexts. I kept all of their refusal letters. Once I came to the library again and out of curiosity filed in just another request. At last I was given this book. It helped me very much to gain an understanding of the history of pogroms. It describes only Denikin’s pogroms. And I collected materials on the archives of ‘АRА.’ I have them partly typed by my deceased wife, partly in manuscripts. In particular, I have in manuscripts two valuable works on the history of Jews written by the professors Loktev and Usov. One interesting thing about these books is that they depict the very significant role of Jews in the development of industry and trade in Russia. In spite of what Dostoevsky 35 wrote.

We reacted with much compassion to the wars of Israel of 1967 and 1973. The break of diplomatic relations between the USSR and Israel didn’t touch me personally, but I was worried about those who lived there. I read books about first pioneers in Palestine even before the declaration of the state of Israel 36. It was a heroic work. It is hard to imagine: mountains, bogs. The youth from all over Europe gathered to create this paradise. Their enormous labor created everything, even before the foundation of the state of Israel.

I can very well remember my friends, who left for Israel and for the West. I welcomed their emigration, was very happy for them. But I myself was too old, and it was senseless to leave. I had no plans of emigration. I didn’t even think of it. It would have been an absolutely different atmosphere for me. My sister Sita, as we called her, emigrated with her Jewish husband Zalman or Zema Ryadko for permanent residence in Israel in the 1980s. At first they lived in a hostel and then they were provided with an apartment. We regularly corresponded with her.

She married Zema through matchmakers in 1925 and I was sure that her marriage with him would be a lasting one. I was 15 years old then. Zalman was a small trader. He died in Israel not long after their arrival. Sita lived with her daughter in Rehovot; I can’t remember her name. The daughter was born in 1930, an engineer, graduated from Odessa Flour-milling institute, calls me sometimes, she is now 71. Sita’s elder son died at the front near the Dnieper River in Kirovograd region. She received a good pension for him from Germany.

My wife Lyubov died in 1997. She had two strokes and she gave up. We lived in Novosibirskaya Street. After that Lev took me to live with him and now I’m staying with his family. My granddaughter Alya lives here, too, she is a student of the Polytechnic Institute, 19 years of age, and my Russian daughter-in-law, Lena. I have very good relations with all of them, but Alya is taking the best care of me. Lena works at school and previously she was employed in the Institute of Space.

I am writing articles on Jews and Jewish history. Here are the titles of some of them: ‘The day of national madness,’ ‘Is it fair to be proud of your nation?’ on national modesty, ‘A month’s work under the motto ‘Jew’,’ ‘On Jewish pogroms,’ ‘Reflections on national issues’ and hundreds of others. Besides, every day I fill in my diaries with what is happening in the world. I don’t stay idle a single day. You see, I am a man from the generation crushed by the world revolution, that’s why my religious life as a Jew came to an end with the establishment of the Soviet Power, as of millions of other Jews. My children don’t attend the synagogue, don’t celebrate Jewish holidays or observe any traditions. They don’t know Hebrew and live secular lives.

I haven’t ever left the borders of the Soviet Union. First, I was prohibited from trips abroad for a long time. And when it became possible to travel, I already was an old man. I corresponded with my sister Peisya-Ita in Israel and with my niece. I could contact them only from time to time. I had an uncle in the USA, and after the war my father received a letter from him through Rostov, asking Father to send his address. Father told us nothing, and wrote to Rostov asking them to answer that they hadn’t found him. Father was afraid. If you had relatives abroad, you could be easily dismissed from work.

The beginning of democratization in the Soviet Union in 1989 was perceived by us with infinite pleasure. We must thank Gorbachev 37 that he undertook the whole business, although pseudo-patriots condemn him for it. Besides, libraries became more open. A lot of publications were released from special enclosed book archives. The most valuable book that I came across was Albert Schweitzer’s ‘Culture and Ethics,’ it had finally superseded the remains of Marxism in me. The basic thesis of Schweitzer is reverence before life.

I am very grateful to the employees of Hesed 38, the place that has become a home for me. I continue to work on the history of Jews. I have always worked on this topic since I retired. I have written an extensively documented history of Jews, containing 990 pages by now. I am looking for a co-author, who could help me finalize it. I offered that to several people, they agreed, but nobody really responded, and I have no habit of pushing people. Besides, I am an author of about two dozen articles written on the history of Jews from ancient time. Some of them are published in the newspaper ‘Ami.’ Hesed helps me very much. From Hesed I receive both humanitarian and psychological help and support. I also received help from the society of rehabilitated citizens, of which I am a member. They handed over to me several parcels with canned food. But that was quite some time before, about eight years ago. I myself don’t really get out of my apartment anymore now.

Glossary:

1 Common name: Russified or Russian first names used by Jews in everyday life and adopted in official documents. The Russification of first names was one of the manifestations of the assimilation of Russian Jews at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. In some cases only the spelling and pronunciation of Jewish names was russified (e.g. Isaac instead of Yitskhak; Boris instead of Borukh), while in other cases traditional Jewish names were replaced by similarly sounding Russian names (e.g. Eugenia instead of Ghita; Yury instead of Yuda). When state anti-Semitism intensified in the USSR at the end of the 1940s, most Jewish parents stopped giving their children traditional Jewish names to avoid discrimination.

2 Pogroms in Ukraine

In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.3 Russian stove: Big stone stove stoked with wood. They were usually built in a corner of the kitchen and served to heat the house and cook food. It had a bench that made a comfortable bed for children and adults in wintertime.