Moris Florentin

Athens

Greece

Interviewer: Lily Mordechai

Date of the interview: February 2007

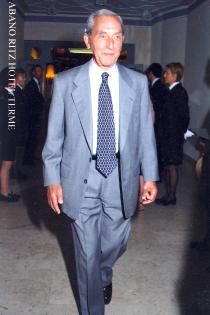

Mr. Florentin is 84 years old. He is a nice man of few words who always smiles and is always willing to help in a kind and calm manner. He and his wife live in a spacious, modern apartment in a nice suburb of Athens, very close to their son and two grandchildren. In their living room they have many different books about Thessaloniki, books with pictures, history books and novels. Mr. Florentin is slim and quite tall; he has expressive eyes and a calm, straightforward nature. He limps when he walks because of a war injury on his right leg. Even so, he is a very active man, he walks a lot, he swims in the summer and he also drives. He retired from his job at the pharmaceutical company La Roche thirteen years ago.

My family backgound

Growing up

During the war

After the war

Glossary:

My ancestors left Spain, went to Italy and then settled in Thessaloniki. In Italy they stayed in Florence and that is possibly where my last name, Florentin, comes from or at least that’s what they used to say in Thessaloniki. They used to tell me that different relatives of my family must have settled in Thessaloniki at least three or four generations before I was born, but I don’t know if all this is true or not. In fact, we used to go to the Italian Synagogue, it was in Faliro close to the sea opposite the cinema ‘Paté’ and it was called ‘Kal d’ Italia.’

I don’t know much about my great-grandparents, I never met any of them; I only met my grandparents on my mother’s side. My grandfather’s name was Saltiel Zadok and my grandmother’s name was Masaltov Zadok [nee Matalon]. They were both born in Thessaloniki. My grandfather was a carpenter, he specialized in furniture making and he owned the best and biggest furniture shop in Thessaloniki, named ‘Galérie Moderne’ and it was on Tsimiski Street [main road of the interwar period in Thessaloniki].

He also owned a furniture-making factory; as long back as I can remember it was behind Tsimiski Street close to the Turkish Baths, there my grandfather had his workshop and part of the factory. Later in time, the factory specialized in making metal beds and was moved close to the train station. Even so, the shop always sold furniture.

My grandparents didn’t have friends because my grandfather worked a lot, even on Saturdays. In his free time he loved fishing and listening to music. He was an amateur fisherman so he would take the boat and go fishing whenever he could. He would also go to a café that played music and sometimes he took me with him. He sat there and drank his coffee silently; he didn’t talk much, my grandfather, but he was a real music lover. That café was by the seafront close to ‘Mediteranée’ [one of the best known and most luxurious hotels in Thessaloniki], I remember it very well.

Concerning his character he was the silent type, he was a bit reserved and he didn’t make many jokes. He wasn’t religious at all, he never went to the synagogue and he didn’t keep the Sabbath. I never met any of his relatives; I don’t think he had any.

My grandmother, Masaltov didn’t work; she stayed home and didn’t go out much. She took care of the house and the cooking, even though they also had a cleaning lady who stayed overnight. My grandmother had a brother, but I don’t remember his name. He had a wife and two children, a boy and a girl but they were much older than me. He used to go to my grandparents’ house every Saturday to keep my grandmother company. He would go on Saturday morning and leave by noon; I think he lived in the same area.

In general, my grandmother stayed home and took care of her grandchildren. I wouldn’t say she was an introvert but she didn’t have much of a social circle besides her family. My grandmother wanted to be more religious but since my grandfather was not, she was not given the chance to do so. They didn’t keep any of the traditions, the Sabbath or eating kosher food, but I remember that we used to have seder in my grandparents’ house with my uncle’s family as well, Viktor Zadok.

They used to live in an area of Thessaloniki called Exohes [area on the outer part of the eastern Byzantine walls, area of residency of the middle and upper class mainly]. Exohes was the whole area from Analipseos Street until the Depot, the bus stop was by the French Lycée, it was called ‘St. George - Agios Georgios [King George] or Vasileos Georgiou.’ It was a two-story house and my mother’s brother, Viktor Zadok, and his family lived on the top floor.

I remember my grandparents’ house; it had two bedrooms, a living room and a dining room. As you went in from the entrance you could see the living and dining room and then were the bedrooms and the kitchen. They had running water and electricity and the house was heated with what we called a ‘salamander’ [big stove for heating the whole house]. You put anthracite [type of charcoal] and it was very effective. They had a garden, which they shared with my uncle; they grew some vegetables and had some flowers too.

Jewish people mainly inhabited the area they lived in, even though there were some Christians as well. I think that the majority of people my grandparents associated with were Jewish, also their neighbors with whom they got along. Their house was not far away from ours so I used to see them almost every day, at the least I would drop in and say ‘Good morning.’

My grandfather died around 1939, before the Holocaust, my grandmother was taken from Thessaloniki to Auschwitz along with my parents, and they probably died in 1943.

On my father’s side I didn’t meet my grandparents. They were both born in Thessaloniki but they died before I was born. My grandmother’s name was Oro Florentin, I don’t remember my grandfather’s name but I have seen a picture of him. My father didn’t talk about them much.

Thessaloniki had a vibrant Jewish community. There were many synagogues; I think there was a synagogue in every neighborhood. I only remember the central one that still exists today, the Italian one and another one close to my house on Gravias Street. The main Jewish area I would say was Exohes, where we lived, even though there were Jewish people everywhere.

There was also an area where Jews from lower social classes lived; it was called 156 or ‘shesh’ as everyone called it. [Editor’s note: The area Mr. Florentin is referring to was actually called ‘151,’ and ‘6’ is a different neighborhood; there were at least 10 Jewish working class neighborhoods in Salonica]. This area was strictly lower class, poor Jews. I didn’t know anyone nor had any friends from there.

Middle class Jewish people were mainly merchants, they had shops with fabrics or other things but I don’t remember any famous Jewish people being manual workers. The main market was by the White Tower; where we lived there were only a few shops. I think both my mother and my father did the shopping but I don’t remember if they had any favorite merchants. There weren’t many incidents of Anti-Semitism but I’m sure it existed because when you heard of one happening it would stay with you.

My parents’ names were Iosif, or Pepo as everybody called him, and Ida Florentin [nee Zadok]. They were both born in Thessaloniki. Their wedding took place sometime in 1919 in Thessaloniki; I think it was an arranged marriage. My father was a money-changer; it was a common profession among Jewish people. I am not sure exactly what he did but I think he bought, changed or sent money abroad, that kind of thing. It had to do with Greek and foreign currency, for example when somebody wanted to buy golden Sovereigns Liras. But I don’t remember that very well because later on he worked in my grandfather and uncle’s business, in the furniture shop ‘Galérie Moderne.’

My mother didn’t work; she cooked and took care of my brother and me. We had a cleaning lady to help her with the housework but she didn’t stay overnight, she left in the evenings. She did most of the housework but my mother was the one who cooked. I don’t remember the cleaning lady very well, in fact I think we changed a few but what I do remember is that they all came from this village in Chalkidiki called AiVat [poor village in the mountains surrounding Thessaloniki, presently called Diavata.], all the cleaning ladies in Thessaloniki came from that village. They were middle aged, Christian women.

My parents were relatively educated people, they had both gone to school but I don’t know which schools. Their mother tongue was Ladino 1 and they spoke it between them. To my brother and me they spoke French; I think they wanted us to learn. They also knew some Greek but they spoke it with a distinct, foreign accent.

My parents usually read in French. I remember them reading the newspaper everyday; they read ‘L’Indépendant’ 2 and ‘Le Progrès’ 3. They would buy it from the kiosk and I remember specifically that my mother would read them as well. They didn’t read Greek newspapers, I am sure of that, and I don’t remember if there were Spanish ones in circulation, if there were I’m sure my parents read them.

We also had a few books in our house that were mainly novels. They weren’t religious; I mean my father wasn’t religious at all and consequently my mother didn’t practice it much, even though I think that she would have liked to. My father only went to the synagogue on Yom Kippur, Pesach and another one or two of the high holidays. Sometimes he took my brother and me along but my mother never came with us. I think the only reason my father went to the synagogue was because his brother was a ‘gisbar’ [cashier of the Jewish community] in the ‘Kal d’Italia’ and he felt obliged. We didn’t keep the Sabbath or eat kosher food.

My parents like my grandparents, were modern people for their time; they didn’t dress traditionally but I’d say in a more European way. I remember my parents having a social life; they went with their friends and had people over in the house sometimes. Their friends were mainly Jewish; I don’t think they met socially with colleagues or other Christians.

When I was really young we used to go on holiday to Portaria in Pilio, without my grandparents. We would go in August and stay for three weeks. After Ektor [Mr. Florentine’s brother] and I got older we stopped going and we spent our summers in Thessaloniki, but anyway we lived really close to the sea so we went swimming every day.

My father had sixteen siblings but I only met four, three sisters and a brother. The family was kind of torn apart because of their differences, and they were out of touch with each other, that’s why I didn’t meet his other siblings. His brother’s name was Samouil Florentin and he was a ‘gisbar’ in the ‘Kal d’Italia.’ Contrary to my father he was very religious. I think that ‘gisbar’ meant he was a cashier for the synagogue. He was married and had two children Anri [Erikos] and Nina Florentin. They used to live in Agia Triada, a quite ‘Jewish’ area of Thessaloniki, as well.

During the war Nina was saved by a Christian man whose last name was Christou; he literally pulled her out of the line when she was about to board the train for Auschwitz. After the war she married him and moved to Canada. The next time I saw her, after the war, she was Christian and so ‘croyante,’ so religious. I found it very strange! Unfortunately, she died in an air crash flying from Thessaloniki to some Greek island. She had two children, one was called Aristoteli and I don’t remember the other’s name, they live in Canada and they are both married.

I don’t know what Anri, Nina’s brother, did during the war but at some point he left for Israel and became a police officer, then he went to Canada to live with his sister and that’s where he died. When we were young we didn’t play together so much, even though our age was compatible. I think Anri was older than my brother and Nina was a couple of years younger than me.

I also met three of my father’s sisters; I don’t remember them very well because we didn’t see them often. His one sister was called Tsoutsa, she must have been a widow, because I never met her husband, but she had a daughter. Her daughter was a bit mentally weak but I don’t know in what way.

Unfortunately, I don’t remember the other sisters’ names they were widows as well, because I never met their husbands. Anyway, I don’t think my father gave them any money so I guess they had their own. We saw my father’s brother and sisters about three times a year, mainly because he felt it was his duty.

My mother had two brothers, Ludovic and Viktor Zadok. Ludovic lived and worked in Paris but died at the age of twenty-three. I don’t know what he died of, but I think it happened when I was very young because I never met him; my mother said he was a very nice person.

Viktor Zadok lived on the top floor of my grandparents’ house with his family, his wife Adina and his three daughters. Adina was like a second mother to me; she was very nice and took good care of us. Their daughters’ names were Ines, but we always called her Nika, Yvet or Veta, and Keti.

Nika lives in Israel, she was married twice, her first husband was an Israeli Jew, Nisim Levi, and they had a daughter, Donna. Unfortunately, her husband died. Nika got remarried to Moris Nissim or Boubis as we called him. He was a friend of my brother’s, Jewish, from Thessaloniki. After the war he moved to Switzerland to work in the Jewish ‘Discount Bank,’ he got a good position and almost became a manager. When Boubis retired, him and Nika left Switzerland and moved to Jerusalem where he had a house. Unfortunately, he got sick and died. At least, now Nika is in Israel and lives with her daughter and her grandchildren.

Veta married Markos Tabah and they had two daughters: Polina, who lives in Israel, and Adina, who got my aunt’s name. Around 1967 Veta died in a car accident. Her husband and she had gone on an excursion with Freddy Abravanel and on the way back they had an accident. They all came out looking fine but Veta had some internal bleeding and died the next day. After Veta’s death, Keti, her sister, married her husband, Markos Tabah. They had one daughter who they named Veta in memory of the deceased Veta. Keti’s daughter Veta married a Christian and became Christian herself.

I would say that my family had closer relations with the relatives on my mother’s side, my grandparents Masaltov and Saltiel Zadok and my uncle Viktor Zadok and his family. My parents saw Viktor often and we, the children, would see each other probably every day, we were very close especially with Nika.

My brother Ektor Iesoua Salvator Florentin, who we call Ektor, was born in 1921 and I was born in 1923; we were both born in Thessaloniki. I don’t remember going to kindergarten or having a nanny at home, so I guess my mother took care of us when we were young. We did have a French teacher though who came to our house to give us lessons. I spoke French to my mother and father but I spoke Greek to my brother. When we were young I used to play with my brother a lot, but when we grew up we weren’t so close anymore, probably because we had different friends.

In the period before the war we moved houses about four times, I remember all of them but I don’t know when or for how long we stayed in each of them. I was born or at least my first memories are from a house on Gravias Street. This was the house of Cohen the dentist, who was quite well known in Thessaloniki at the time. He had four children, three sons and a daughter; two of the sons were about my age: Tsitsos and Morikos Cohen. At the end of this street there was a small synagogue which was very nice but I don’t remember what it was called.

Then we moved to a house on Moussouri Street close to 25th Martiou Street. This was a big house too; we lived on the second floor and below us lived Sam Modiano. This house had a garden but it was overgrown and neglected. The last two were on Koromila Street, the third one had two big bedrooms, a kitchen, a living and dining room and two big verandas; it had no garden and was on the third floor of the building. Our neighbors were a married couple, he was Jewish and she was Russian and they didn’t have any children, my mother was friends with the Russian lady and would go and visit her once in a while. The last place we lived in before we were forced to move to the ghetto was much smaller; it didn’t have a garden and it was on the second floor.

I don’t know why we moved so often but all these houses were rented. We would always take with us our furniture for the living room, the dining room and the bedroom. In all these houses we had running water and electricity and they were all heated with ‘salamanders.’ These houses were all very close to each other and also very close to my grandparent’s house. I remember most of our neighbors being Jewish.

I would say the atmosphere in my family was very good and generally, we were closer to our mother than we were to our father. My father worked a lot. He opened the shop around nine in the morning or a bit earlier, then he would come home at noon, go to work again in the evening and come home around eight or nine in the evening. At noon we all had lunch together. My father’s work was in the center of Thessaloniki, quite far from our house, it was ten stops by tram.

Financially, by the standards of Thessaloniki at the time, we were probably a middle class family, we didn’t own any property but we covered our needs sufficiently. My family didn’t own a car and I don’t remember when the first time I went into one was, but I got my driver’s license after the war, not with the intention of buying a car but just learning how to drive.

Some Sundays we went out to eat by the seaside on 25th Martiou Street, not far from where we lived. There were some ‘tavernas’ by the seafront and we went there, not often but we did. At home I would say that my mother cooked traditional Sephardim dishes, not so much Greek cuisine.

The first school I went to was the ‘Kostantinidis School,’ which was private. When I first went there, they put me in the second grade of elementary school, based on my date of birth. A little in the year they realized I was too advanced, so they promoted me to the third grade, that’s why I finished school a year earlier than other people my age. So apparently I covered the whole first and second grade at home with a teacher. I stayed in that school for two years and for fifth and sixth grade I went to another private school, the ‘Zahariadis School,’ which was very close to our house on Moussouri Street.

I don’t remember my friends from these schools but they both had a majority of Christian students. I know there were a few Jewish people like John Beza in ‘Zahariadis’ but I have no vivid memories.

For gymnasium I went to a public experimental school like the ‘Varvakios School’ in Athens, it was a very good public school. I remember some of my teachers, the Chemistry teacher Menagias and the principle who taught us Physics. He loved me very much probably because Physics was my favorite subject. Every time we had to do homework he would present mine to the class saying it was the best. But I had a secret: I used to study Physics from my brother’s book who went to the French Lycée. You might wonder what the difference was but French books phrased physics differently to Greek ones. In Greek books they start by saying, ‘If you take this, you will observe this will happen’ instead of explaining the main principle first. I preferred the French way, it was more serious and that probably explains the story with the principle.

I got along with both my teachers and my classmates. I remember some of my classmates were Giannis Tzimanis, Thanasakis Flokas, the son of the famous confectioner in Thessaloniki, Stelios Halvatzis and others. There must have been Jewish students in my school but my friends were mainly my classmates who were Christian. On weekends I went out with them, we would go to parties or to the cinema; it was really rare to go to bars at that time especially at such a young age, not like nowadays.

I never experienced Anti-Semitic behavior in school or at least anything that traumatized me. Sometimes someone would say the typical nonsense like ‘Dirty Jew’ but I think people say that sometimes when they are angry, even if they don’t really mean it.

When I was going to school, I didn’t have much free time because the classes were quite difficult or anyway quite intense. I would go in the morning and I was back by two in the afternoon. In the evening I did my homework for the next day. I didn’t have any private lessons, only a few Mathematics classes before my entrance exams for the university. I only had English classes in a British Institute in Thessaloniki. I never did any Hebrew or Jewish history lessons.

I didn’t have hobbies other than sailing in the Sailing Club but even though I was a member, my friends weren’t. With my friends I usually played basketball but we never played any football.

At that time the educational system was different, we finished gymnasium [Greek equivalent of high school. It used to be 6 grades, but nowadays it is 3 years, followed by three Lyceum years.] and got a gymnasium diploma and then whoever wanted to continue with their studies took introductory exams in the polytechnic school or university or any other school they may have wanted. In fact you could take the introductory test for more than one university, like I did. I wanted to study in the Polytechnic University of Thessaloniki to become an engineer but unfortunately I failed the entrance exams. As I still had time I also took the exams for university and I passed in the Agricultural University of Thessaloniki. The university was in an old building on Stratou Avenue, it is not there anymore.

I remember we had some really good professors like the Physics Professor, Mr. Kavasiadis, the Chemistry Professor and this other one, Rousopoulos, who was our Geology Professor. Even though it wasn’t my first choice I was relatively interested in what I was studying and the university was quite demanding. It required attending the classes, being concentrated and studying, not like now where they pass the lessons without going to classes, at least that’s what I see. I don’t think anyone was checking attendance but the system was such that it was necessary to attend classes and everybody did so.

I did three years of university and then, in 1943, during the German Occupation 4, I stopped and left for the mountain. Throughout these years I continued living with my parents and my brother, it was always the four of us.

My brother Ektor went to the French Lycée. When he was finishing elementary school in the French Lycée a law was passed that the Greek nationality was only given to people with a Greek elementary school diploma. So he came to the ‘Zahariadis School’ with me for sixth grade and then went back to the Lycée. That’s why he finished school a year later than he should have. I had a completely different group of friends to my brother probably because we went to different schools. He finished school in the French Lycée, he got the two Baccalaureates and then he started working for Sam Modiano who had an agency office [legal representative of foreign companies].

Ektor didn’t want to go to university so he got this job with Modiano, who was our neighbor in the house on Moussouri Street. This was his only job until he left Thessaloniki around 1943, a little after we moved to the ghetto. He left for Israel with his girlfriend at the time, Nina Hassid, to whom he got married after they got there. I think they left via Evia and then through Turkey. When they got there they stayed in Netanya first and then in Tel Aviv. My brother worked in a diamond-cutting factory and then gradually created his own factory.

They have two daughters, Ada Schindler and Zinet Benderski. Zinet was the name of my brother’s wife’s sister, who she lost: after the liberation she was taken to a Spanish concentration camp because her father was Spanish. Zinet has two children, Sharon and Daniel, who are both married, and Ada also has two children, but they are much younger.

I didn’t know of my brother’s whereabouts until one year after the war when my uncle Viktor told me he was alive. Now we have a very good relationship with him and his family. We don’t go so often but every time they come we see them and also sometimes we arrange to meet abroad. I see my brother every four, five years on average but we talk on the phone every week.

The war was declared on 28th October 1940 5, that’s when I finished school; I was seventeen at the time. I was in Thessaloniki during the bombings in 1941 a bit before the occupation started. The bombs were mainly dropped towards the customs area, which was far away from where we lived, so we didn’t really feel them. Of course we could hear the noise of the bombs but you have to understand that it’s not like today; the airplanes didn’t drop lots of bombs then, so the damage was more limited, or at least that’s what I think. For my family it was scary but not as much as for other people who lived closer, we didn’t really feel much during the bombings.

After I finished school, I went straight to university. We already felt the effects of the war then, there were curfews and it was really hard to find food, we got some food from the villages, just about enough to survive. For me the war started in 1941 with the occupation, when the Germans entered Thessaloniki. They marched in with their typical characteristic discipline, German manner; they had so many trucks and tanks. I remember my parents and me being very scared.

Officially, the war started in 1940 when Metaxas 6 said ‘No’ to the Italians but the occupation started later and we kind of expected it because we would see, read and hear that the Germans were coming down the north side, they had been to Bulgaria and Serbia and then came Greece’s turn. When the Germans invaded, the Italians headed to the south of Greece; here in Macedonia we were under German Occupation unfortunately. A lot of people headed south then, to Athens or just anywhere in the Italian ruled south.

The first measure the Germans took targeted specifically against Jewish people was when all Jewish men of Thessaloniki had to gather in Eleutherias Square 7. I went with my brother because we were within the age range, around twenty years old. I am not sure about my father; I think he didn’t come because he was considered too old. They made us do humiliating gymnastic exercises under the sun and then they assigned us to different places to do forced labor outside Thessaloniki.

They wanted to build rail tracks for trains; the work was really hard especially with the Germans over your head not letting you rest for even a minute. I managed to avoid the forced labor because I had a Christian friend who took me with him where he was, close to the Agricultural School, I became a member of the forced labor team over there. I did absolutely nothing there, I just sat there from morning to night, but I still had to go every day.

I am not sure how they informed us that this gathering in Eleutherias Square was happening but I think it was through the Jewish Community. During the war I didn’t think that the Jewish Community in Thessaloniki acted in the right way. The chief rabbi then was Koretsch, who was German but that wasn’t important. The problem was that he didn’t give good information to the Community members. He was telling them that it was going to be fine, they would just go to Poland to move there. He didn’t say anything about concentration camps or what might happen when they got there.

I don’t know why he did that but I thought that it was very mean of him because if he had leaked the right information that something bad was going to happen to them then maybe more Jewish people would have tried to save themselves. Some people said he knew the truth all along but I don’t know if that’s true, it might be.

At some point, the Germans emptied all the businesses and shops owned by Jewish people, especially merchants and all their merchandise was being confiscated. Around 1942 a Greek man who was co-operating with the Germans turned my grandfather’s shop ‘Galerie Moderne’ into a restaurant. From then on we were living off our savings and things became even more difficult.

The most important anti-Jewish law was to put all the Jewish people in one area of the city what they called the ghetto 8. The ghetto was between Faliro and Agia Triada and between Mizrahi and Efzonon, in that area. We were forced to move there around the beginning of 1943, between January and February. I don’t know how we were informed we had to move or how we knew where to go in the ghetto, I just remember that one day we left our house on Koromila Street and moved to the apartment in the ghetto.

We were all a bit crammed in that apartment but I guess it was still a roof over our heads. It was a very small place with two rooms and a dining room, I don’t remember if we had heating. All we really took with us was clothes; we left a lot of our furniture in our last house on Koromila Street because the owner moved in when we left. That’s why when the war finished we retrieved some of our furniture.

My father and Viktor Zadok were both looking for a way to move to Athens, Viktor found a solution first and brought my grandmother Masaltov to stay with us in the ghetto; until that point my grandmother was staying with him. Because of my grandmother, my mother and father couldn’t escape from the ghetto and so they had to stay there with her. This is something that really makes me sad because I think it was really selfish on my uncle’s side to leave my grandmother with us like this, my mother was just too nice! So Viktor and his family managed to go to Athens a bit after we moved to the ghetto.

In the ghetto we had real difficulty finding food; my father was in charge of this and most of the times he bought things from the black market or products that came from villages. After three weeks or a month, I left for the mountain 9. At the time I would say that politically I was quite ‘left’ but I wasn’t a member of any political party or group. In my university, EAM 10 was very strong among the students so I heard about their activities in the mountains and I wanted to follow them. They said, ‘Since you are wanted by the Germans anyway why don’t you go to the mountain.’ I thought about it a little while and decided to go.

EAM was an organization that was 90 percent communist; its military branch was called ELAS 11 and there as well most of the members were communists. This organization was created during the occupation. I was sure I wanted to go to the mountain and since my parents didn’t oppose my decision I went, and I left the four of them – my mother, my father, my brother and my grandmother – in the ghetto.

Later on I found out my brother left the ghetto as well and went to Israel. I think my brother didn’t come with me because he had different plans with his girlfriend. As for my parents and my grandmother I am assuming they were deported 12 from the ghetto to Auschwitz were they must have been exterminated, I would think that people their age were sent directly to the gas chambers. The day I left for the mountain was the last time I ever saw them.

It was the 20th or 21st of March 1943 and I left with a friend of mine called John Bezas. He lived really close to our apartment in the ghetto, at some point I told him about what I was going to do and he decided he wanted to come with me. So that day, we wore working clothes and caps, we took the star off and passed the ghetto guards with ease like nothing was going on.

We found our contact and he took us outside Thessaloniki to a place where we could start ascending the mountain. He said, ‘Sleep here tonight and I will bring another fifteen people tomorrow.’ The next day he came back alone and said, ‘Stay here another night, I will come tomorrow with twenty-five people.’ We thought, ‘Of course we will wait, if so many more Jewish people will come as well.’ But then on the third day he showed up alone again. I never understood why no more young people came to the mountain, but I think that they had a hard time leaving their families.

After our two days waiting for the people that never showed up we started walking towards Giannitsa, sometimes we would come across a carriage and they would take us a few kilometers further. I remember on Axios Bridge we found a café and we decided to take a coffee break – John Bezas, our contact and me. As I opened the door to enter the café this guy tells me, ‘You’d better not go in there it’s full of Germans.’ I don’t understand how he realized we were fugitives or that I was Jewish, but he did. ‘You’d better not go inside,’ he said and probably saved our lives with his words.

So we didn’t go in and left in a rush, we got to Giannitsa and from there gradually we climbed up Paiko Mountain, this was our first mountain. Then we went to Kaimaktsalan another mountain close to the borders with Skopje [today Republic of Macedonia], and from there we walked across the whole of Macedonia from the borders with Albania up until the sea. We went from village to village trying to avoid the Germans; we were not ready for confrontations yet.

The ELAS people taught me how to use weapons because I hadn’t been to the army yet. After a while we were full of lice; we went there clean and naturally all the lice came on us, on our hair but also all over our body and clothes. I watched the others trying to de-lice themselves and their clothes; they would sit for hours. I never did that because I figured that I would kill ten and then twenty would come on me; there was no point in trying but it was really, really itchy. I guess that after all a person can get used to anything. I mean the situation on the mountain wasn’t the best but compared to what was in store for us in Germany it was paradise.

The contact left us with an already organized group of people from all over Greece, Kavala, Drama, Serres and Thessaloniki. There were very few Jewish people in my group I only remember one, a tobacco worker from Kavala nevertheless during our moving we crossed paths with maybe another ten Jewish people from different ELAS groups. The groups were all over the place but they all had a leader who was called Capitan Something, for example, Capitan Black etc.

We all had nicknames, I was Nikos and John Bezas was Takis; that was enough, the people on the mountain were not interested in finding out anything more. What I mean is that if you wanted to tell them they would listen but there was no obligation to discuss where you came from or who you were. There was zero Anti-Semitism and I don’t even think I ever heard the word Jewish.

These teams communicated with each other by sending messengers, people that took the information from one group to another. I was a simple soldier, only for a period of two months I was in charge of a sheepfold. As I was supposedly an agriculturalist I was in charge of the project. We found an abandoned village and we gathered all the sheep with one or two locals that knew how to make cheese. They would take the sheep to pasture and make the cheese after.

When I went back to the group my friend John Beza wasn’t there, the English had come looking for people who spoke English so they took him with them. I was a bit upset because if I hadn’t been in the sheepfold I would have been able to go with them, as I spoke good English. On the mountain there were certain groups of the English army that were sent to observe our tactics against the Germans, give us advice on how to act and information about where to go etc. I think it would have been better to be with the English because next time I crossed paths with John he was well dressed, clean with a uniform.

We were almost constantly on the move because of the Germans, sometimes if the village was ‘free’ we stayed in schools and houses, if the village wasn’t free we stayed in the forest without anything, no tents, all we had on us was our clothes and our weapon. In West Macedonia there were certain villages that were ‘free,’ this was the ‘Free Greece’ as it was called but of course there was always the fear the Germans would come so we never stayed long.

In order to find out if a village was free or not, there were certain people that observed and informed us. Sometimes we were welcome and sometimes not, but even then the villagers didn’t have a choice but to give us food. So we ate in the villages but we didn’t take much with us because we couldn’t carry much and we usually found something to eat.

In fact, I don’t think I even lost much weight. Only one time we went eight days without any food or water, it was a really rough time, the Germans had surrounded us and we couldn’t escape from any direction. We stayed in places we could hide without any food of course; we ended up eating the leaves from trees. I don’t remember what happened in the end but we found a way out and then went to a monastery where we ate a lot. We didn’t have connections with the church but in the monasteries they had to accept us.

There was always the fear that we would get involved in a battle, especially after some point that the English started blowing up rail tracks in the Tembi area. They wanted to cut the train connection between Thessaloniki and Athens because the Germans were using the trains for their purposes. So whilst the English were working on blowing up the rail tracks, we would guard the surrounding area. We were their protection; thankfully I never came face to face with them.

The Germans were furious about these damages and they were trying to think up a way to neutralize the English teams or us, the Resistance, to save them the trouble of fixing the rail tracks every time. It was then that we found ourselves in a village called Karia on the north side of Mount Olympus, above Rapsani.

We always set up watching points with binoculars to see what was happening. At some point we saw a German squad from far away, we saw they had trucks and they were about four hundred, we were only eighty men. Even so we were fortunate because the road the Germans were on crossed a little river that had hills on the left and right side, these hills had many trees on them and that’s where we were hiding.

On their way the Germans saw the little river and decided to take off their clothes and start bathing. They knew we were in the village and they were coming for us but they didn’t know we had left the village and that we had positioned ourselves ahead of them, so as to ‘welcome’ them one or two kilometers further down. When we saw their condition we started going down the hills shooting and exterminating them. Many Germans were killed on that day, the rest were so lost that they left leaving their clothes and weapons behind.

As we were coming down the hill I was almost at river level ready to jump in a ditch, at that moment I got shot, the bullet entered my thigh from the front and exited at the back of my leg. Of course I fell down and started bleeding a lot, another soldier came and tried to put me on a mule; in the meantime most of the mules were loaded with guns, weapons and other things the Germans left behind. It was impossible for me to sit on the mule because my leg was completely dislocated. I said, ‘I have a broken bone you can’t put me on a mule, it’s too high.’ He said, ‘don’t worry,’ he put me on the ground, he tied my leg up the best way he could and put a sort of blanket over me, and said, ‘They will come and take you with a stretcher.’

I thought to myself they will never come. It started getting darker and darker and then this German airplane started flying over the area, shooting randomly in case anybody was still there that they could kill. I started putting soil and grass on my blanket to camouflage myself, that was all I could think of doing. Anyway, I don’t know how long I stayed there, I must have fallen unconscious but suddenly people started shouting my name, it was eight villagers and a soldier with a stretcher, they put me on it and took me to the village, which was about three quarters of an hour away on foot. There was an English doctor there who put a dressing on my leg and then we left straightaway because we couldn’t stay in that village any longer.

We moved to another village that had a hospital in the school building. I don’t know if anyone died but four or five of us got injured, the other ones were lightly injured. The most seriously hurt were a man with a similar leg injury to mine and another man who had been shot in the head.

Anyway, that day a doctor, a surgeon, had come to the mountain by the name of Theodoros Labrakis, his brother was the Labrakis that was murdered in Thessaloniki after the war. He had a clinic in Piraeus called ‘White Cross’ and he was an excellent surgeon. He used anything he could find, paring knives, Swiss army knives and saws and operated on the guy with the head injury. Thank God he took the bullet out because until then that man was very violent, swearing, throwing chairs around even assaulting us. Anyway he survived.

In my case the bullet had come out and the bone was in pieces. Another doctor who was there said, ‘We should cut off his leg because we don’t have anti-gangrene treatment and if he gets gangrene he will die.’ Labrakis said, ‘No I will not cut it off.’ Later on, he told me that he had been boiling an axe for three days in a row just in case he had had to cut my leg off. Fortunately I didn’t get gangrene, but I was in so much pain he had to give me morphine. After a few days I started asking for more and he said, ‘Enough with the morphine, I don’t want it to become an addiction.’

So I owe my leg to Dr. Labrakis who unfortunately died one or two years after we came down the mountain. He only treated a few people in that hospital and then he left, he was also moving from place to place.

I got shot on 6th May 1944 and from then on I was being moved from hospital to hospital, we were constantly changing villages because of the Germans. One day, shortly after I managed to keep my leg, we were in a hospital somewhere and we found out that the Germans were coming to that village. Everyone wanted to leave but they didn’t know what to do with us.

They took the three of us, the man with the head injury, me and the other man with the leg injury to a tap of running water outside the village. Of course this was very dangerous but they didn’t know what else to do with us. I think we stayed there for four days, us with the leg injury couldn’t move so the poor man with the head injury would take what we called ‘boukla,’ a wooden bucket for water, and he would bring both of us water to drink. One day the Germans came to the tap, we were totally silent and thank God they didn’t discover us because they would have definitely slaughtered us.

In the meantime my injury had been infested with flies and worms and it was itchy. Four days later I saw the doctor and I told him, ‘Doctor look what’s happened to my leg.’ And he said, ‘Very well, at least they ate up all the puss.’ He cleaned it of course but I couldn’t believe what he had said: ‘They ate away all the puss.’

So I was hurt in May 1944 and until September they were carrying me on the stretcher from place to place. The man with the head injury was fine after some time so I was left with the other man with the leg injury. He was from a village called Aiginio in Macedonia, he was the father of this man who caused trouble in a nightclub and killed someone; I don’t remember his name but I know he is out of prison now. I don’t know if his father is still alive but I doubt it because he was much older than me then.

The time I spent on the mountain we probably walked the whole mountain range of Pindos from the borders of Ipiros to the borders of Serbia and from Albania until the sea, village to village. When I left the ghetto I took nothing with me, I was wearing a pair of black boots but after a while they were completely destroyed. The situation with our shoes was a drama, in fact a lot of the time we were barefoot. I am not sure what we were wearing, I guess things they gave us in the villages and then at some point the English gave us some uniforms.

Looking back I would say that going to the mountain was a good idea. I can’t say that I have kept friends from then because the situation was different up there but still we were all very close to each other, really. Most of the people there were communists, members of the K.K.E. [Communist Party of Greece]; I wasn’t a communist but I didn’t mind them because I do believe there are some good things in this ideology.

I think my most profound experience was that I realized the stamina of the human organism and by saying stamina I mean the way man and nature complete each other and the way the human organism can cure itself. For example there was this guy named Dick Benveniste – he is dead now – who got diphtheria on the mountain – no hospital, no doctor, no medicine, nothing. At that time the Italians had made some kind of agreement and a lot of them came to the mountain. There was this Italian man that took care of him, he would take him out of his tent to do his needs and fed him, any way he could because Dick couldn’t even open his mouth. In the end he recovered, he went back to Thessaloniki, he married and had children. He died not so long after the end of the war but still this showed me how much the human body can endure.

I remember I never even got a headache or a fever, if we wanted to wash we would go to the river which was freezing cold but it didn’t bother us. I stayed with the same group almost from the beginning to the end. There weren’t any women in my group but occasionally, when we were on the move, I saw a few, not many though.

When the liberation finally arrived everybody came down from the mountain but it didn’t happen all at once, it happened in segments from the south to the north, I think Thessaloniki was liberated in October 1944. But places like Kozani and Lamia had been liberated before so a lot of Resistance soldiers came down the mountain from there.

I guess what the Liberation meant for us was that the enemies had left, someone took over from there and there were elections but I was out of it because I was in the hospital. We found out about the liberation from the villagers and after certain areas were free, I was taken to the hospital of some big village. I think it was in October 1944 they took me to Thessaloniki, to this hospital in Votsi after the Depot, it was a makeshift hospital in the palace of a pasha. The first thing they did was to de-lice me, the English had some machines and I don’t know what they put on me but all the lice were gone from my body and my clothes.

As my injury didn’t heal I had to stay in that hospital until February 1945, almost ten months. Of course, back then there were no surgeries to put screws and metal in the leg so what they did was that they put concrete to open the leg so that it stuck back by itself. The human organism is a very strong thing and even though my leg stuck back, it got stuck differently to what it should have and it became six centimeters shorter than the other one.

I didn’t have to pay anything to the hospital, everything was free: my stay, the food. At some point I got anchylosis on my leg and there was a nurse there, her name was Eleni Rimaki – I remember her clearly – and she said, ‘We need to break it, you can’t stay like this.’ It sounded easy in theory but the pain was unbearable. The other guy with the same injury as me stopped trying after a week he couldn’t bear it. I did it for a month and a half. It was not like physiotherapy or massage, it was practically breaking the knee but I’m happy I did it because now I can even ride a bike.

One time I was in Italy visiting an old friend and he said, ‘I will take you to this surgeon to examine your leg.’ The surgeon said, ‘I can lengthen your leg if that’s what you want but I see you’re walking very well with your orthopedic shoe.’ So I didn’t do anything. It never hurt me, and now sixty-four years later, it just started hurting. Now I went to this doctor who said, ‘You have osteoarthritis and we need to do joint plastic surgery. We’ll cut the bone and we’ll put a plastic one to lengthen it, we’ll see what happens.’

After the hospital I stayed in Thessaloniki with Miko Alvo, his brother Danny and an elderly aunt of his. When we found each other after the war we arranged a meeting and he said, ‘You will come and stay with me.’ I agreed and I was very grateful because I didn’t have anywhere to go.

For two years, between 1945 and 1947, I was working for the Greek English Intelligence Center in Thessaloniki and living with Miko. I was doing translations because I knew English. My supervisor there was a man called Stahtopoulos, later on he was charged of something – I am not sure what – and he ended up in prison.

After I came out of the hospital I had an intense feeling of happiness because I got myself out of this situation and I could walk. We created a group of friends and we went out and drank our ouzo in such a happy way, like we were saying, ‘Finally the occupation is over and we can enjoy certain things.’ In that group of friends there were both Jewish and Christian people: Mimis Kazakis, a lawyer, Takis Ksitzoglou, a journalist, Klitos Kirou and Panos Fasitis, both poets, Nikos Saltiel and the girls, Anna Leon and Dolly Boton.

At some point soon after the end of the war I went to get a passport so I could visit my brother in Israel and the officer said, ‘You can’t have a passport.’ I asked him, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘You can have a passport only if you denounce communism etc.’ I asked him again, ‘Why? I am not a communist, I don’t have anything to denounce’ ‘You are.’ ‘I am not.’ And then he said, ‘No passport’ and I said, ‘I don’t want one.’

Six months later an officer came to my office and said, ‘If you file an application for a passport we will give it to you.’ Nothing else. And he left. I was a bit shocked that an officer had come all the way to my office to tell me that, but I filed the application and got my passport. Around 1949 or 1950 that was, and I went to Israel to see my brother after all of this, it was a very strong experience.

After World War II, there was the civil war 13, basically all the resistance communists from the mountains had hid their guns, which was exactly what their opponents, the government party feared. After the civil war came the great exodus of the communists and they went to places like Yugoslavia, Georgia, Taskendi, which is in Georgia, Kazakhstan etc. A lot of them stayed for good but some of them returned later on.

As for me, politically I had no involvement but my beliefs were left then and are left now. We felt the civil war in our daily lives because there was turmoil in Athens, nothing was functioning properly, to the extent that there were battles in Sidagma [very central area in Athens]. Emigrating never crossed my mind but I know a lot of people who did and went to Israel but also Canada, Italy, the USA.

When I was working for the Greek English Intelligence Organization I met a couple of English Jewish officers including a man named Shapiro. At the time I was walking with a stick because the wound hadn’t healed properly, I still had a band over it that I changed every day and occasionally little bones would come out of it. The doctor had said not to worry because the wound would heal after all the bones came out. After ten or fifteen little bones had come out the wound truly healed.

However, Shapiro said he would put me in an English hospital because at the time penicillin had just been discovered. So I went and got a shot of it. There was this Scottish nurse there who would go around saying, ‘I can’t believe we are giving this expensive drug to Greeks.’ Everyday the same thing, she annoyed me very much, to the extent that I regretted going. In fact, I thought English people were weird because they had a little bucket where they did everything; they washed their hands and their face, as well.

Anyway I got the penicillin shot but it didn’t do anything to me, as I didn’t have any bacteria for it to kill. In the meantime I got in touch with my uncle Viktor Zadok, who was in Israel, and he said, ‘What will we do with the shop?’ I am not sure how my uncle tracked me down but I should assume it wasn’t very difficult.

The shop was there but the merchandise was gone and it wasn’t in a very good condition. My uncle went to Israel like my brother and then, after the liberation, he went back to Athens. Then he came to Thessaloniki to see the state of the family business, and finally he settled in Athens. Viktor tried to make ‘Galerie Moderne’ work but he couldn’t and shortly after, he gave up and left for Athens.

In 1948 my uncle said, ‘Come to Athens and work for me.’ I had nothing left in Thessaloniki so I did. I didn’t have any property but my uncle Viktor had the house my grandparents and he used to live in before the war, and it was in a good condition when he found it. After the war the family members I kept in contact with were my uncle Viktor Zadok, my brother and my uncle Viktor’s daughters, especially Veta. I used to see her a lot socially, probably about every two weeks until her tragic death in 1962.

I moved to Athens and I was working for my uncle from 1948 until 1953 when I opened my own business. I had an agency office that imported floor polish, wax and plastic domestic utensils. I lost a lot of money because the plastic utensils I imported were expensive compared to the Greek ones in the market. I ran my own business for four years and then my wife continued it for quite a few years after I left.

My next job was in Hoffman – La Roche, Pavlos Aseo had the company’s representation in Greece at the time. I didn’t know much about pharmaceuticals but I learned the job quite quickly. Later on the company La Roche made its proper branch – La Roche Hellas – in Greece and I continued working for them. I became commercial manager for the vitamin section of the company until my retirement in 1993.

I never faced any problems with the fact that I was Jewish in any of my jobs. When my wife was in charge of the business the manager of the company we were importing from wanted to visit from England, he did, we met him and it all went well. The next year the owner of the company wanted to come so I took him out for lunch to Kineta. We ate in the only ‘taverna’ that was open, which was not a luxurious one. Anyway we sat down and there was a picture on the wall of the greatest Resistance Capitan.

As we were eating he said the word ‘andartis.’ [Editor’s note: Greek expression for one who revolts or, one who resists, but after WWII it was codified to mean resistance fighter.] I asked him, ‘Where do you know that word from?’ He said that during the war he had been sent by the English, by parachute, to Mount Olympus. He said his real job was a doctor but his father insisted on him working for their company.

We started talking about when, where, how he was there and we found out that on 6th May 1945 the English doctor who treated me first was him. His name is William Felton and I will never forget it. He came to Athens again later on and tried to convince me to import another product of his but I didn’t buy it in the end. He had five children and later on he became General Director of ‘Hallmark,’ the company that makes greeting cards.

My wife’s name is Ester Florentin [nee Altcheh] but everybody calls her Nina. She was born in 1932 so we have nine years of age difference between us. She speaks Greek, Hebrew, French, English and Ladino. She lived in Thessaloniki with her family until 1943, then they moved to Athens and hid in Iraklio [suburb of Athens], in the house of a Christian family. That family wanted to keep Nina as their own child and so betrayed the rest of my wife’s family – her mother, her father and her brother. They all went to Auschwitz.

Nina stayed with the Christian family during the war but after the liberation she left for Israel, she must have been about thirteen at the time. She went to Israel with one of these boats that took Jewish people there, she had no money and stayed in a kibbutz for a year. Then she went to school in Jerusalem for five years and now she speaks perfect Hebrew. In Greece she had to stop going to school after the sixth grade of elementary school.

Her father and brother died in the concentration camps. Thankfully, her mother Kleri Atcheh returned after the war; she weighed just thirty-six kilos then. Her mother went to Israel to find Nina, imagine that they saw each other after such a long time. After a short time in Israel her mother returned to Greece, Nina stayed there a little longer in one of her aunts’ house.

When Nina came back to Greece in 1950 she was seventeen years old. That’s when we found ourselves in the same group of friends; they were Viktor Messinas, Sam Nehama, Markos Tabah, Veta Tabah, my cousin, Nina and another friend of hers that is in Israel now. So, I met her in 1950, we became friends, we loved each other and then we got married in 1951. When we married she was nineteen years old and we have been married for fifty-two years.

I didn’t know Nina before the war but I knew her mother very well. She really wanted us to get married and since things were going in that direction anyway, she was very happy for us. I wasn’t looking for a Jewish girl to marry; I would have married her even if she had been Christian but since it happened naturally I didn’t mind. Now I am happy she is Jewish because from what I have seen from my son, who is married to a Christian girl, things are easier for a couple if they have the same religion, even if that is agnostic. I am not religious at all but my wife is more than me; I think it’s because her family, when she was growing up, was very religious.

We got married in the synagogue here in Athens, we had a rather small marriage because we didn’t have much money at the time. Of course, we invited all our friends and family but we didn’t have a reception or anything. We celebrated alone in a hotel in Paleo Faliro. Until then I was living alone in an apartment on Aiolou Street in the center of Athens. When we married we moved to Kipseli on Eptanisou Street. I was making some money working for my uncle, I don’t know if Nina was taking any money from her mother but we were just about getting by the first years.

After two years we had our first child, our daughter Ida, she was probably a bit rushed but it doesn’t matter now. I don’t remember my wife’s father’s real name, I never met him because he died in Auschwitz. After the war, my mother-in-law married Alfredo Beza. He was a very nice man and we were very close to them. For about forty years, every Saturday, we had lunch in their house, in the beginning just my wife and me, then with my children and even more recently with my grandchildren. Unfortunately, Kleri died five years ago.

I would say that my wife cooks traditional Sephardic dishes I like the pies very much and my favorite sweet dish is ‘sotlach’ which is a kind of sweet pie with milk and syrup. My favorite food though is Greek and it’s ‘fasolada’ [typical Greek bean soup].

We have two children a girl, Ida Nadia Florentin, named after my mother Ida, and a son, Iosif Tony Florentin, Iosif like my father. They were both born in Athens, my daughter in 1952 – she will be 54 at the end of the year – and my son in 1956 – now he is 51 years old. When Ida was born we were living at my mother-in-law’s house on Kalimnou Street in Kipseli. When Tony was born we had moved into our own house, which was very close to my mother-in-law’s.

Their mother tongue is Greek but they had extra-school English classes in a ‘frodistirio’ [foreign language school] and private French lessons. They also heard a lot of Ladino because of their grandparents and then at some point my son decided to also learn Spanish and went to the Cervantes Institute for two or three years. My wife and I always spoke Greek in front of them and also between us. They didn’t go to the Jewish school because I don’t think it existed back then but even if it had we wouldn’t have sent them there.

Growing up, the children had a very close relationship with their grandparents, my wife’s mother and her stepfather Alfredo. Alfredo was a real grandfather to the children and he loved them like his own. We never had disagreements on their upbringing and we would see each other almost every day. The children loved their grandmother and grandfather very much. Nina did the cooking in our house but every Saturday we would have lunch at my mother-in-law’s house.

The children grew up in a not very religious environment. Of course, they knew they were Jewish straightaway but as I am not very religious, I didn’t explain much to them. Their mother and grandmother taught them a few things about Judaism; my father-in-law wasn’t very religious. The Jewish holidays like the seder night [Pesach] we used to spend with the children’s grandparents. We didn’t really celebrate other holidays, for example Rosh Hashanah we exchanged some presents and that was it.

My children didn’t have many Jewish friends because they both went to Greek schools. I would say their upbringing was quite liberal, they brought their friends home and went out with them. We had no problem with that. We used to go on holiday for fifteen days in August to Tsagarada in Pilio, to a hotel; now we have a summerhouse in Porto Rafti [place on the outskirts of Athens] but we bought that twelve years ago when our children were already much older.

They also used to go to a summer camp for a while in the summers so we got sometime for ourselves. I don’t remember sending them to the Jewish camp but they went to various other ones like the Moraitis Summer Camp in Ekali [northern suburb of Athens].

I was always interested whether they had problems in school because of their religion so I asked them a few times and they both said they hadn’t faced any problems. We talked to them about the war and what had happened when they were much older; I think their grandmother talked to them more than us because she was more ready to talk about her experiences. My wife couldn’t because she was reminded of her brother who died, and I never really talked to them about my injury and my time on the mountain. Now they know everything, at some point I wrote my story down and they read it, but I didn’t talk about it much.

When the children were young I was very busy so I didn’t really have time to read the newspapers. I only used to read Greek newspapers, ‘Eleftherotipia,’ when it came out and before that ‘Vima.’ Also, the first few years we avoided going out with our friends a lot, but by the time we moved to the Androu Street house in Kipseli [densely populated area in Athens] the children were old enough to be left alone. We went out with our friends to the cinema, to ‘tavernas’ to eat, to the theater. They were mainly other Jewish couples. Of course we had some Christian friends but we didn’t see them as often.

With our Jewish friends, especially in the beginning we always talked about the war, later on we still talked about it, but not so much. With our Christian friends we didn’t really initiate discussions on Jewish topics but if they wanted to ask something we were very open to answer to them. That’s not to say that there were topics I felt embarrassed to discuss with them, I just didn’t choose to a lot of the time.

We also traveled a lot; we have been to England, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Cyprus, Turkey and Israel. We used to go as part of organized tours for pleasure, usually it was only my wife and I. I think with the children we only went to France together once, for a marriage or something because we have some family there. For business I only went to Switzerland and I used to go alone on these trips.

My daughter Ida was born at a point when our financial situation was terrible and we had to struggle for a while but, thankfully, by the time my son was born things were better. I have a very vivid memory of Ida’s childhood because when she was born and for a few months after she was very sick, to the extent that our pediatrician said, ‘If she is meant to die she will die.’ That was not a good thing for a doctor to say to a mother and a father.

Anyway a while after, she started getting better and then she relapsed again. We took her to a doctor, a professor named Horemis, and he said it was tuberculosis so he started treating her for that. Thank God there was another doctor, a very good one, Saroglou, who said, ‘I disagree with the professor.’ He took all his books down and he was telling me, ‘All I am doing is spending time on your daughter.’ He discovered that it was a disease called ‘Purpura’ where you get this red rash in certain places so he said stop all the tuberculosis medicine and give her this.’ A little while later she recovered and now she is perfectly healthy

That was a really rough period for my wife and me. Ida and Tony went to kindergarten and elementary school in a private school named ‘Ziridis School.’ Then for gymnasium Ida went to ‘Pierce College,’ the American College of Greece. She studied in the Pharmacy University of Athens for four years and came out with a pharmacist degree. Then she went to Paris to do her master’s in molecular biology for another three years.

When she returned she got a job in a drug warehouse and then in the National Research Institute. She quit her job a year ago and she did a degree in London on the Montessori technique for kindergartens. This year she didn’t manage to find a job but she is still looking. She is not married and she doesn’t have any children.

Tony had his bar mitzvah. He studied with the rabbi of Athens at the time whose name was Bartzilai, he said his words very well even though he was a bit stressed. It took place in the synagogue of Athens in the morning, we had invited a lot of people and then at night we had a party in our house where he invited his friends and we invited ours.

From Tony’s childhood there is one incident I remember very vividly. He was a boy scout from the age of six and then one day, when he was sixteen, they went walking from Athens to Parnitha [a mountain close to Athens]. That day it snowed a lot and we lost their tracks for a while. Anyway they made it back but we were really scared for a while.

For gymnasium, Tony went to the ‘Varvakios School,’ which is a good public, experimental school. He passed in the Polytechnic University of Athens and became a mechanical engineer, then he went to Paris for a postgraduate diploma in the mechanics of production and renewable sources of energy for six years. He got a distinction for his dissertation and was also awarded by the French academy.

In the six years he was there we visited him once. They both stayed with us during their studies in Athens but they both lived alone when they came back from their studies in Paris. For me my children’s’ education was very important I wanted them to do something that would educate them but that they could also find a job with. When they left for Paris we were sad in a happy way because they had left to do something good for themselves.

Now, Tony my son is manager in D.E.P.A., the Public Gas Supply Corporation of Greece. When he was in Paris he got married to a woman from the Czech Republic but he got a divorce from her and then married again, in 1985, Ioanna, who is Christian Orthodox, so they had a civil marriage. They met in Athens; they lived together for three years and then got married. She did all her studies in Germany and now she is a German teacher at university. They have two children: Philip, who is eleven years old, and Faedon Florentin, who is nine years old.

Right now the children don’t have a religion but they know both about Christianity and Judaism. They talk about Purim and get Rosh Hashanah presents but they have a Christmas tree during Christmas etc. My wife has taken them to the synagogue and their mother is absolutely fine with that.

They live in the building opposite us; my wife and I never put pressure on them to live close to us but when we moved here from Maroussi [middle class area in the north of Athens] they decided they wanted to buy a house close to us. We have very good relationship with our grandchildren and also with my son and his wife. We see our grandsons very often. Of course there might be periods of ten days or so that we haven’t seen them but in general they come and say ‘hi’ and stay with us a few hours.

I talk to my son and my daughter almost every day, sometimes we get together and eat but not something standard like it was when their grandmother was alive. We usually gather with my son, his family and my daughter for certain Jewish holidays like the seder night or other occasions. We gather in our house and my wife does the cooking.

Nowadays in the summer, we go to our summerhouse in Porto Rafti from the 1st of July until mid-August. It is a two-story house so my grandsons usually come with us and stay on the same floor as my wife and me. My son and his wife stay on the second floor. My grandsons love Porto Rafti. We swim in the sea, they play around, I think they really love that place. Then around the end of August we go to Abano in Italy for fifteen days. Abano is a spa town, my wife has mud baths and I swim in the swimming pool half an hour a day. I love that place and every year I can’t wait to go there.

As for my grandchildren there are certain things I would do different if they were my children. The oldest one is very smart but he doesn’t study or read books and I think his education is lacking important things like orthography, proper Greek language or just more depth in what he studies. I think he should read a book outside school, a children’s book, but I don’t want to intervene because their parents spend enough time on them.

I have a good relationship with my grandchildren but my wife has an even closer one, I try but they just have more contact with her. Sometimes I want to say certain things but I don’t want to intervene and insist on anything. Until now I haven’t spoken to them about the war and my stories.

More recently, my wife and I had a very nice group of friends but unfortunately two of them died and the other one can’t see very well so he doesn’t drive. Now we see a lot of Matoula Benroubi and her husband Andreas, we see them almost once a week. We go to ‘tavernas’ and eat, we don’t go to the cinema, I haven’t been to the cinema in five years. I don’t really know why. Anyway we also talk about the past about how things used to be and at least I enjoy these conversations very much.

I am not involved in the Jewish community or the different committees and I never was. I have a computer and e-mail but right now I haven’t set it up because when we moved I put one computer on the side and then my son brought me a laptop and on that one sometimes I push the wrong buttons and I ruin everything. But anyway, at some point I took some computer lessons, thankfully, but my wife didn’t. I think she should have done. My grandsons know everything about computers, while to me it’s the strangest thing and so they help me sometimes.