Moisey Marianovskiy is a short thin man with blue eyes. One would never tell he is a Jew from the way he looks.

He lives with his daughter Olga Marianovskaya’s family in a spacious and nice apartment in the very center of Moscow.

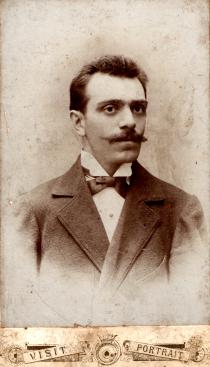

He has his own study where he keeps his books. There are pictures and photographs of his friends on the walls.

There are also portraits of Soviet commanders on the walls. One of them is Marshal Zhukov 1.

Moisey is a hospitable and sociable man. He gladly tells me the story of his life, but talking is tiresome for him.

He is busy taking part in public life, but he is often ill. It was not that easy to schedule an interview with him.

The interview took place on 26 September 2004.

The day before he celebrated his 85th anniversary at the Moscow Union of Jewish invalids and veterans of war at the Israeli cultural center.

We were often interrupted by his friends calling to greet him. One can tell that Moisey has many friends who care a lot about him.

My family background

I was named Moisey after my paternal grandfather Moisey Marianovskiy, which was quite common in Jewish families. I was born in Novyy Bug near Kirovograd [Yelisavetgrad before 1924, Kirovograd in 1930-1934, Kirovo in 1932 - 1937, Ukraine, 250 km south of Kiev]. My father’s parents, his sisters and brothers and their families lived there and so did my parents after they got married. From what I know, Moisey Marianovskiy was a forester. I know no details, though. My paternal grandmother Bluma Marianovskaya was a housewife. My mother told me that she was a great cook and this was what my father had said. The family was doing well. My grandfather’s children were used to working hard. My grandfather and grandmother died before I was born and I don’t know their dates of birth or death. I have vague memories about my father’s brothers and sisters My father died in 1922 shortly after I was born, and my mother and the children moved to Kirovograd. After that we hardly ever saw my father’s family. I can’t even remember how many sisters and brothers my father had. I remember uncles Tula, Noah and aunt Shprynia. They passed away before the Great Patriotic War 2.

My father Efroim Marianovskiy was born in Novvy Bug town approximately in 1878. I don’t know what kind of education he got. All I know is that he died on 16 April 1922. He worked as a clock repair man and that was how he supported the family. I cannot say for sure whether my father was religious. At least I tend to think he was moderately religious. He celebrated holidays and gave his children Jewish names. My father died from a lung disease. He was buried in Novvy Bug. I don’t remember him since I was two year and a half when he died. My mother, older brothers or sisters hardly ever spoke about my father. They had to struggle for survival. Our situation was very hard. Mama had to take care of six underage children. We moved to Kirovograd where my mother’s sisters and parents lived. My mother’s relatives helped us to survive and we had closer relationships with them than we did with my paternal relatives.

My maternal grandfather’s name was Samuel Budnichenko. I don’t know my grandmother’s name, though. She was just called grandma in the family. My grandmother and grandfather had also died before I came into this world. My mother told me her father was self-educated. Mama told me her family had always strived to learn things. They were a very closeknit family. There were five sisters and one brother. They were born and lived in Kirovograd. They were Lisa Val, nee Budnichenko, Polina Zbrisskaya, nee Budnichenko, Ksenia Goldberg, nee Budnichenko. Her husband perished at the front. Mama older sister’s name was Rachil Budnichenko. We called her Rusia. My mother’s only brother’s name was Isaac Budnichenko. Mama’s parents were not religious. However, they celebrated Jewish holidays as a tribute to traditions. I remember Chanukkah, a merry and delicious holiday. We were given candy, nuts and other sweets. On Pesach we ate matzah. We were poor and it wasn’t often that we could eat to our hearts’ content. It’s been along time since we left Kirovograd and regretfully, I cannot remember my mother brother or sisters’ names or their dates of birth.

My mother Clara Marianovskaya, nee Budnichenko, was born in Kirovograd in 1880. She only had primary education. She and her sisters studied with a melamed in their childhood. However, my mother was well-read as she was very fond of reading. And was an interesting conversationalist. She was a well-cultured person, though she was just a cleaning lady in her life. Mama and her sisters spoke Yiddish in the family, though we spoke Russian in our family. I do not know any Yiddish. Mama had no professional education. Like other Jewish women she was supposed to be a housewife, but life happened to be different for her and she had to get a job to support her children. Mama was a wonderful person. Even the fact that she raised all her six children and they became honest and decent people speaks for itself. She taught us to be hardworking and caring. She also taught us to love our country. We were a close family. Mama was a heroic woman providing support to six children. We grew up to become nice people. Mama was very kind. She always wanted to help those who were in trouble. She knew how it felt when life was hard. We, her children, loved her dearly and were outstandingly grateful to her for what she did. Mama died in Moscow in 1964. She had a stroke and became bedridden for 5 years. She was paralyzed. My sister Revekka took care of her. My sister Emilia and brother Yakov lived far from Moscow. I had my own family. My wife and I did our best to help my sister to take care of our mother. My mother was buried in the Vostriakovskoye cemetery in Moscow.

My mother had six children: two sisters and four brothers. We were all born in Novvy Bug town. My older sister Emilia Marianovskaya was born in 1903. We called her Milia at home. Emilia finished a gymnasium. She married Abram Leichtmann, a Jewish man from Moscow, and adopted his last name. Her husband was fond of revolutionary ideas. My sister had a son named Efroim. My sister was a well-read and intelligent woman. Milia also got fond of revolutionary ideas. Her party leadership sent her to Uzbekistan in the late 1930’s. Emilia and her family lived in Tashkent [about 2900 km southeast of Moscow]. She worked in trade unions. She started her career at a plant and was gradually promoted to the republican level. She worked hard to take care of common people’s problems, trying to improve their living conditions. She also initiated construction of health care centers and rest homes. Though we lived at quite a distance from one another my sister and I had very warm and close relationships. I visited her in Tashkent in 1970 when I went to the birthday anniversary of her husband Abram. Emilia died in 1985. She was buried in the town cemetery in Tashkent. Her son and grandchildren live in Tashkent now.

My brother Yakov Marianovskiy was born in 1906. After finishing a gymnasium Yakov was recruited to the Soviet army. He became a professional military and was transformed to Moscow. He married a Russian woman from Moscow. Unfortunately I don’t remember her name. They had a son named Samuel. Yakov was a pilot during the Great Patriotic War. He was at the front and had many military awards. After the war Yakov finished the Moscow Air Force Academy. He was promoted to the rank of colonel. After the war Yakov and his family lived in Rostov-on-the-Don [about 1000 km south of Moscow]. Yakov had an Air Force regiment under his command. Yakov died in Rostov-on-the-Don in 1982. He was buried in the town cemetery. He had had a surgery on the adenoma and at that time this was a very complicated operation. It happened to be lethal.

My sister Riva, Revekka Marianovskaya, was born in 1910. She and mama lived in Moscow. She never got married. She went to work at the HR department at a plant. Her management forced her to quit her job, when struggle against cosmopolitism started in the late 1940s 3. She went to work in trade. Riva died in Moscow in 1980. She was buried in Vostriakovskoye cemetery in Moscow.

The next was Shimon Marianovskiy, born in 1914. Shimon finished Moscow machine building technical school. He was foreman at the machine building plant in Moscow. He also trained schoolchildren in turner’s profession. He was mobilized to the army on the first days of the Great Patriotic War. He perished at the front line near Viazma [about 225 km west of Moscow] at the very start of the war in 1941. I said ‘good bye’ to him, when he was going to the front. I was in the army and was on my way to a military school. I happened to be in Moscow at this moment and went with him to the recruitment gathering point. Since then we’ve sent many requests about him, but the answer has been the same: “Missing”. However, we heard the true story of what happened. Shimon (or Senia, as we called him) was wounded. They were sent to Moscow by a military train. German airplanes bombed the plane. All those in the train were killed. Nobody even buried them.

I had a twin brother – Alexandr Marianovskiy, Sasha. We were born in 1919. We were the youngest in the family. Sasha died in 1926. He slid on ice, fell and hit the back of his head. He came home and said to mother: “Mama, I will die like my friend did”. Mama exclaimed: You don’t say so, Sashenka”. He said, “I fell on the back of my head and I’ve had headache for a few days. This happened in Kirovograd. Mama told me to wait for a doctor at the gate. When the doctor came I guided him to the room. I must have sensed that grief had struck our household. I remember all details of the day as if it all happened yesterday. The doctor stayed a few hours. Two days later Sasha died. He was buried in the town Jewish cemetery. My brother and I were very different. I am different from the rest of my family. None of my kin had a pug nose like I do. I have no trace of typical Jewish appearances. People often take me for a Russian man.

Growing up

I don’t remember anything about the Novy Bug town. I was too young when we moved to Kirovograd. It was a nice little town buried in verdure and acacia blossom. Our whole big family lived in one room in a shared apartment [Communal apartment] 4. Most of our co-tenants were Jewish. There was a big Jewish population in Kirovograd. There was a mill factory and a buttery in the town. My older brothers went to work at this factory when they grew old enough. There were no other jobs and my brothers and sisters wanted to help mama in her effort to support the family.

I didn’t face any anti-Semitism then. I don’t think there was any and besides, nobody discussed this subject in my presence. It did not occur to me that people were segregated by their origin. Mama worked from morning till night. I had no nanny. I didn’t go to a kindergarten either. There were no kindergartens then. My sisters and brothers looked after me and taught me letters and numbers. They also gave me common errands to do. I went to a primary school at the age of 8. This was the nearest Russian school. I studied well. I finished 5 years in this school.

In the early 1930’s Ukraine was struck by terrible famine 5. Only God knows how we survived this famine. Mama had swollen legs. She always gave me whatever food she could, but I was still always hungry and even fainted from starvation. Shimon was a Komsomol member 6. He often went to villages on his Komsomol errands. He returned from there swollen from hunger telling us that the situation was even worse than ours. Employees from the town were often sent to villages to help farmers with harvesting. Many people in town were dying, though townsfolk always received minimal bread rations. Fortunately, our family survived.

In 1932 my older brother Yasha was in the army in Moscow. He became an officer. He wrote that there were better food supplies in Moscow and it was easier to find a job here. In 1933 our family moved to Moscow. Shimon went to work at the electrical plant named after Kuibyshev. He was a worker. Later I followed into his steps in Moscow.

We lived in Izmailovo district in Moscow. At that time this was a suburb of Moscow. We moved into a 19-meter room in a shared apartment. We hardly had any furniture. There was very little space. When my brother went to work I took his place on the bed. We were very poor. Those were hard times. We hardly ever ate to our hearts’ content, but at least we did not starve. Gradually our life was improving. I finished secondary school in Moscow. I worked at the plant and studied. This was hard. I worked the 2nd shift at the plant and had no time to do my homework. .I also had to help mama about the house. Besides, I also wanted to meet with my friends, so I did have little spare time. I was glad I earned my own living. We lived in this room in the shared apartment till the early 1940’s.

I joined Komsomol at school. I led an active way of life. We enjoyed living in Izmailovo. We used to play football and volleyball in the nearby forest. We had makeshift playgrounds and everything else, but we had lots of fun. My friends were our neighbors’ children. Later we went to the army together. There were many Jewish families living in the vicinity, but we never divided people by nationality. There were never any demonstrations of anti-Semitism, particularly that I had no typical Semitic features. Later I became a member of a workers’ collective. My friends and my sisters’ and brothers’ visited us at home and mama always welcomed them. We celebrated Soviet and family holidays, but we did not celebrate Jewish holidays. We were not religious. We were far from observing any holidays or traditions. We were young and had other interests. We were fond of sports, went to parades and sang Soviet revolutionary songs about “how good it was to live in the Union of Soviets”.

I was good at all subjects. However, I liked physics and history more than other subjects. I did not consider continuing my education since I had to work to earn my living. Before finishing school I quit the electrical plant and went to work to the car manufacture plant named after Stalin. This plant is now named after Likhachev 7. I worked at the turner’s unit and also, worked at school. I became a candidate to the membership in the party at this plant. I believed in the ideals of communism and honesty of the party ideas and deeds. This was a legendary plant, the pride and hope of the young country. Director of this plant Ivan Likhachev [Ivan Alexeyevich Likhachev (1896-1956). Soviet state and business activist, director of the biggest Russian car manufacture plant, Minister of medium machine building] needed workers badly. He arranged for a whole group of young workers to get a delay from recruitment to the army for a year. I was also included in this group. On 5 October 1940 I was recruited to the army. Having being recruited to the army a year later I escaped the Finnish campaign [Soviet-Finnish War] 8.

During the war

I served in Porkhov town near Pskov [about 400 km northwest of Moscow]. In six months I was sent to a military school. At the weekend my whole platoon accompanied me to the station. This happened on 22 June 1941 [the Great Patriotic War started 22 June 1941]. Nobody in our regiment knew that the war began. I took a train to Kalinin [about 200 km north of Moscow]. The train stopped and I came to the platform. I could not grasp what was going on. Somebody was playing an accordion, somebody was crying. I asked somebody, “What’s going on?” And they replied, “Soldier, don’t you know? It’s the war.” The regiment that I had left was at the northwestern border, but nobody knew what was happening. About one and half-two weeks before this happened the TASS (Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union) announced that there were no grounds whatsoever for unjustified rumors about Germany. After the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Agression Pact 9 was signed I stopped having any doubts in this regard. Vice a versa, there was the feeling that this pact established friendly relationships between the two countries. But what happened in reality was that Hitler just cheated on Stalin. We happened to be not prepared for the war. I had served on the border with Germany, but we did not notice any movement of German troops. There were no signs of German attack. Later I got to know that 3 hours after the guys saw me off to the railway station the regiment was encircled by Germans. When I heard that the war began I rushed to see the military commandant of the station. I asked him what I was to do next. I thought that it might well be that I had to go back to my military unit. He told me that I ought to move on to where I was assigned. I was heading to Gorky [about 400 km east of Moscow] tank school, but on my way there I was to make my appearance at the district military committee in Moscow.

My middle brother Shimon in Moscow was also recruited to the army and I went to see him off. He went to the front and I headed to Gorky tank military political school. When I arrived at Gorky I found out that all cadets were allowed a monthly leave. I also got this monthly leave, but I decided it was my duty to go to this school due to the start of the war. Before everybody else arrived I worked in the kitchen washing the kitchenware and peeling potatoes.

Later soldiers from the military units destroyed at the frontline started arriving at the school. They told awful stories about the war. It was clear the army was not ready for the war. Later it became everybody’s knowledge that this happened due to the wild policy of Stalin. Before the start of the war Stalin destroyed the officer staff and military commanders [Great Terror] 10. Over 50 thousand officers were executed for the charges of being enemies of the people 11. This weakened our army significantly and there was no doubt about it. The reequipment of the army was initiated before the war. It was never completed. There was no sufficient new equipment available and the old equipment was good for nothing.

In Gorky I saw a terrible view for the first time. We lacked air planes to ensure protection of the town. German planes acted with impunity. A German bomber dropped a 1T bomb onto the plant. It fell between two buildings and the walls collapsed. Supervisors, however, did not allow people to leave the buildings saying that it was just panic. Hundreds of people perished. This was the first time I saw death. This happened on 25-27 June 1941.

We took an advanced course at my school. The cadets like me had already learned serving in the army. We could shoot, load and knew all other required operations that we were supposed to know. By October 1941 we were given the rank of lieutenant and graduated from the school. I was sent to tank brigade 187 and appointed a company commander. I became a commissar, [Political officer] 12 and then I got a tank company under my command. At that time commissars and commanders had equal authority. I didn’t last long as commissar. When the unshared commanding authority was introduced, I was appointed commanding officer of a tank company. There were three tank squads in the company. There were 3 tanks in a squad and 10 tanks in a company.

We did not have enough tanks at the start of the war. T-34 were the best tanks. There were only 1000 T-34 tanks available and this was certainly far from sufficient to oppose Germans in this cruel blood shedding war. There were also Т-60 and Т-70 tanks manufactured at the Gorky machine building plant. They were very vulnerable. They had easily destructive armor and automobile engines. They were weak engines and weak cannons. Our forces were in a very difficult situation at the beginning of the war. The English helped us a little providing tanks. Their tanks were worse than our “thirty fours”. They were light “Valentine” and medium “Matilda” tanks. They had strong armor, but also one big shortcoming. They were equipped either with armor piercing or splinter shells. So, if there were armor piercing shells these tanks were inefficient against infantry, for example. Americans also supplied some tanks to us at the beginning of the war. These tanks were commonly called “a common grave for seven.” They were no good for the war. For example, they had seats with velvet tapestry inside. They might have been good when Americans struggled against unarmed Indians etc., but they were useless in the war that we fought. They also used gasoline and were often subject to self ignition. Gradually Americans modified these tanks to improve their structure. Germans also designed powerful tanks like Tiger, Panther, etc. However, our T-34 tank with an elongated cannon and a crew of 4 was the best tank of the Great Patriotic War. By the end of 1942 the plants manufacturing these tanks that evacuated to the Ural increased the manufacture quantities.

I was at the frontline in the Briansk and later in the Moscow direction. Our brigade did not retreat. There was Moscow behind us, there was nowhere to retreat. I was inside a tank on battlefields. I gave my commands and executed the orders I received from my commandment on the radio. We had telephones or radios. Some tanks had phones some were equipped with radios. We supported our infantry as best as we could on battlefield.

We stayed and slept in the woods. In winter we installed tents or slept in tanks. We took every chance to take a nap in a tank. We did not have timely supplies of underwear and clothing. For example, at times we received warm clothing in April or May. At night we just took off our warm jackets that got wet during a day and then we got into a tank wearing these wet jackets. Tanks were not heated, of course. None of designers took into consideration that we would have to stay in tanks, when it was freezing outside. Who cared? For our military commandant the only important thing was that tanks could move and shoot. Nobody cared about people. The infantry had more chances to get warmer. It was terrible to get into these cold steel tanks. It was really horrific. Here is what happened once. One of commandants from the division headquarters arrived to our location. We accommodated him in a tarpaulin tent, which was supported just by two sticks. It was pouring, the tent got wet and heavy and collapsed. One stick stabbed the headquarters officer in his throat and he died.

We basically had normal food supplies. The army did not starve, but there were hard times as well, particularly in spring, when it was difficult to deliver food products to army units. At such times we suffered from hunger. We had a field kitchen that cooked for us. We also received 100 grams of vodka. These 100 grams were called “narkomovskaya” (narkom – “people’s commissar”) since it was provided based on the order issued by Minister of Defense. Our logistics people submitted lists of staff for vodka provisions before a battle. The battalion went in attacks and then less than half survived, but vodka was still provided for the whole list of staff. We always had much vodka available.

We appreciated a possibility to shave. We also tried to have some fun. We rubbed snow or poured ice cold water on ourselves and also competed in whose teeth were stronger. The one who could bite through thin wire won.

In spring 1942, when I was in tank brigade 187, I was wounded and sent to a hospital. After the hospital I was assigned to the 23rd Guard tank brigade. There was a patriotic movement during the war, when people bought tanks and sent them to the army. For example, a few writers and poets, laureates of the Stalin’s Award [editor’s note: it was awarded by the Soviet of Ministers of the USSR for outstanding achievements in science, literature and art. The award was established in 1939], contributed the money they received to the plant to manufacture a tank. This tank was assigned to the 23rd tank brigade where I served.

When I returned to the front after the hospital, the situation there stabilized a little. Germans were defeated near Moscow and Stalingrad [Stalingrad Battle] 13. This was the turning point and our forces started moving in the western direction. We already struggled for the Ugra and Dnepr Rivers, etc. Battles for Smolensk [about 350 km west of Moscow] began. My units took part in the operation to liberate Spas-Demensk, Kaluga region [about 180 km west of Smolensk]. These were hard battles and I had to use my wits. I have very bright memories about how we decided to fight for a hill near the town. We decided to attack it at the night time. We lit headlights to make an impression that there was a bigger tank group attacking. The tanks were moving in circles to deceive the enemy. The Germans were scared, so we managed to cheat them. After hard and blood shedding battles we captured the hill and then the town. I was awarded an Order of Alexandr Nevskiy [Editor’s note: Order of Alexandr Nevskiy was established on 29 July 1942. It was awarded for special merits in the defense of the USSR] for this operation. This was a smart and witty operation that did not result in big losses for us, but the gains were significant. We headed to fight for Byelorussia. There were also hard battles during crossing the Dnieper. General Zakharov, Commander of our front, decided to attack the enemy on its flank. This operation was also successful and in 1943 I was awarded an Order of Red Banner 14 In August 1943 I was wounded in my eye and was sent to a hospital in Moscow. After two weeks in hospital I returned to my regiment.

The hardest battles were at the Mogilyov-Minsk roadway. Some of them were outrageously savage. We managed to capture a radiogram of Hitler, who ordered commander of the Mohilyov group to head to Minsk [about 600 km west of Moscow]. Our objective was to prevent this army group from stopping our forces fighting to liberate Minsk. Colonel Yershov, Brigadier, and commanding officer of the 2nd battalion Alexandr Pogodin were killed and I was the only commanding officer left. Alexandr Pogodin was killed right before my eyes. The brigade commissar was wounded. He was transported to the rear in my tank and I moved to the tank of Alexandr Pogodin. Ivan Shtokolov was the mechanic and driver of this tank. There were hatches on both sides of the tank and we were looking through them. Alexandr sat on one side and I sat on another side in the tank. I was talking to him, when I suddenly felt something wet under my feet. I looked down – there was blood on my feet. This was Alexandr’s blood. His head was cut off by a splinter and was hanging on the tank’s armor and I was talking to his head. We buried Alexandr Pogodin in a field in the evening and installed a wooden board with his name on his grave.

Commander of the Front ordered me to take command of the brigade, though I was very young (I was just 24 years old). We were at the Mogilyov-Minsk highway at the time. This didn’t make me feel happy, but this was what I had to do... We tried to encircle this grouping of German troops. In order to escape the encirclement Germans decided to do a horrible thing. They gathered the population from nearby villages (children, women and old people) around Mogilyov [about 800 km southwest of Moscow] and made a live shield of them hoping that we, tank men, would not shoot at them. I sent a squad commander to cut the German columns from our citizens. The people scattered around taking their chance. Of course, some were killed, unfortunately. The decisive point happened on the 6th or 7th days. Germans were constantly sending additional forces while we had to fight to the end. We had an order to not allow Germans to approach Minsk. In this battle our tank brigade was supported by infantry. We called them motor infantry, but in fact, they rarely had a chance to get a ride on our tanks. There were many dead and wounded in the battle. The situation was very severe. This was the 6th day already and the tension reached its peak. At one moment our troops faltered. At this moment I jumped out of the tank and carried the banner of our tank brigade. When the tank men saw the banner, they started fighting to the end. Then the Germans started surrendering. I was wounded but stayed on the battlefield. I was slightly wounded and could manage for a few hours. Thousands of Germans surrendered in the end. When we encircled the Germans they started offering us their jewelry. There were heaps of gold and silver jewelry around me. They begged us to be merciful to them. None of us touched anything. One hour later we moved to a different area. This huge army of prisoners marched toward Moscow and then along the streets of the capital. This was a show arranged for Muscovites by the commandment and the government. They demonstrated how miserable those prisoners of war were and how our Soviet army could be victorious and also, that the end of the war was near. For this Mogilyov operation I was nominated for the award of the Hero of the Soviet Union 15 in June 1944, and I received this award on 24 March 1945.

Then operations were held one after another. After finishing one we started preparation to another. Soon we directed our efforts to liberation of Western Byelorussia. This included liberation of, Navahrudak, Grodno [over 900 km west of Moscow] etc. In Grodno Germans established a big ghetto and eliminated it before our offensive killing all inmates. I did not know about these death camps before the 1980’s, but when in Grodno, I did not see anything. We were hurrying to the Polish border heading to reach Koenigsburg, Berlin and end this war victoriously as soon as possible. One of those days I was severely wounded.

We faced particularly adamant resistance near the Osovets fortress [over 900 km west of Moscow]. This happened on 13 August 1944. I was wounded 3 times when at the front, and it always happened in August. Osovets was located in flood lands at the border with Poland. It was an old Russian fortress that Germans chose to defend their lines. I had a battalion under my command. Our Commander of the Front decided to attack and capture the fortress. We had an infantry penal company assigned to our tank battalion. The military were sent to penal units as punishment for various violations. The only way for them to serve their punishment was to either die on battlefield or get wounded which was officially called ‘washing off one’s punishment with blood’. They were dying in their majority. Almost all in this penal company died during this attack on the Osovets fortress.

I had all tanks of the brigade under my command. The objective was challenging. The tension was enormous. The Brigadier poured me a liter of spirits before the attack! It might have knocked anybody down. I drank it, but I felt like I had just had some water. I was in the rank of major. I can remember it as if it happened yesterday. A new brigadier was appointed. He summoned me and said: ‘Well, this is going to be an uncommon operation. The Commander ordered to attack and capture this fortress’. It was fortified indeed. There were numerous pillboxes and one meter thick walls. No cannon balls could break them. There was an artillery preparation before the attack, but it did not help. There were swamps on one side of the fortress and ancient oak trees on the other. The road to the fortress was impassable. I lined up the battalion and announced that I would go first and they were to follow me and be brave. Besides everything else, the fortress was on a hill and Germans could fire at us point-blank. Besides there was only a narrow path to the fortress and there was no way to turn left or right. We could only move one after another. I said: ‘Guys, this is what we must do: if your tank is hit you must remove it from the path by whatever cost. You must make sure that the tank following you can move on’. And so we moved on. The fight was hard and blood shedding. The Germans could see us plainly and they fired at us hard. A German shell hit my tank. Volodia Iudarik, commander of the tank, was severely wounded. He had his arms and legs cut off, but he managed to get out of the tank. He died the moment he left the tank. He died from loss of blood. The driver managed to remove the tank off way. I was wounded an instant later. I was wounded all over with shell splinters. However, at the very last moment I managed to look at the fortress and saw our guys breaking into it. However, we lost almost all battalion and the penal company. When the commanding officer heard that I was severely wounded, he gave his permission to send me to a hospital in the rear. This saved my life. For this operation I was awarded an Order of the Combat Red Banner 16.

I started a new life in a hospital in Moscow. My ward was the ward of deadly wounded patients. Every day we were in the care of Zinaida Ordzhonokidze, a volunteer nurse and an exclusively nice person. She was very ill herself. She had swollen legs and hyper tone, but she never failed to enter our ward at 6 a.m.. Her husband was Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze. [Editor’s note: Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze (party pseudonym ‘Sergo’) 1886-1937: activist of the Communist party and Soviet Union. Red Army commander during the Civil War. After the revolution, Minister of heavy industry in the last years of life. He is thought to have been poisoned by murderers sent by Stalin.] Once it happened so that there were just the two of us in the ward. The rest of my companions in the ward had died. I said: Zinaida Andreyevna, I remember an obituary about your husband. It said that he died from a heart attack’. She looked down and relied: ‘I wish it had been true.’ I did not grasp the meaning of what she said! I believed what newspapers wrote and knew no details of the story. This was the first time it occurred to me that not everything newspapers wrote was true.

I suffered from awful pain caused by a nerve injury. The doctors gave me drugs and since the pain strong, I received a lot of them. Instead of standard 10 drops I got almost half glass to calm me down. I was exhausted and suffered a lot. The tips of my fingers ached awfully. A splinter from the tank armor injured a nerve trunk. One night I fainted. The doctors called Professor Shliapoverskiy, a Jew, a very talented doctor and an intelligent man. He asked what happened and the doctors and nurses told him the story. He decided to operate on me. He X-rayed my hand and saw little splinters that he removed masterfully. This was a unique surgery and I started to recover. However, I never fully recovered. I was still exhausted and was became an invalid of the second grade. I spent in hospital almost two and a half years with some intervals. I was in hospital on the Victory Day as well.

After the war

On 24 March 1945 I heard that I was awarded the title of the Hero of the Soviet Union for the Mogilyov operation. On 7 April 1945 director of the hospital gave me a leave to go Moscow to receive my awards. In Moscow Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet 17 awarded me the golden Star and the Order of Lenin. 18

I was also awarded an Order of the Great Patriotic War Grade 2 19, also for liberation of Western Byelorussia, for the operation in Osovets. I also have an Order of the Combat Red Banner. In 1985 I was awarded an honorable Order of Labor Red Banner [Order of Labor Red Banner was established on 7 September 1928. It was awarded to individuals, enterprises, institutions and work collectives for exclusive merits in serving the USSR in the area of industrial, scientific, public of community activities] for fruitful educational activities in Moscow Energy College.

The military unit where I fought honors and remembers its heroes. It’s deployed in Novograd-Volynskiy. Every year on 9 May I visit the unit to meet with the soldiers of my former military unit and celebrate the Victory anniversary. These are very warm and kind reunions, but unfortunately, fewer and fewer of us manage to make it there with every coming year. There were 4 heroes of the Soviet Union in our military unit. Our photographs are on the stand there.

I honor and bow my head before the two individuals and my military commanders at the front line. They are Bagramian [Bagramian, Ivan Hristophorovich (1897-1982), Soviet military commander, Marshal of the Soviet Union, Hero of the Soviet Union twice. During the Great Patriotic War he was an army commander, since 1943 he was commander of the 1st Baltic and 3rd Byelorussian fronts. In 1955-56 he became Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR, in 1956-58 he was director of the Military Academy. In 1958-68 Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR, Head of the Rear services of the Soviet armed forces.] and G. Zhukov. I served in the 33rd army under Zhukov’s command for some time. I fought at the Moscow direction and Marshal Zhukov was Commander of the Front. I have photos of Zhukov and Bagramian that they gave me personally. I knew Bagramian. He was a nice person. He invited me to his home. He lived in the Arbat Street in Moscow. We talked very frankly. It hurt to hear the panegyric speeches addressed to Brezhnev 20 who never performed any heroic deeds at the front, when we faced death and shed our blood on battlefields.

Marshal Georgiy Zhukov was a great person and a great commander. His participation in this war played the decisive role in our victory over Germany. I admire his strategic talent. During the war Zhukov was sent where the situation was dangerous. I told my students and comrades how America treated their Commander Eisenhower. They elected him president. What did we do to our great commander? We mixed him with dirt. That was what Russia did! It’s absolutely horrible! Zhukov wrote a wonderful book about the war: ‘Memoirs and thoughts’. They did not want to publish this book because of Brezhnev. Zhukov was told: ‘You must emphasize the positive role of Brezhnev. He replied: How can I do it? I’ve never met him before. And I’m aware ‘talents’. And they said: ‘If that’s your answer, there will be no book’. And Zhukov made a trick. He added: I’m very sorry I never met Leonid Brezhnev, when I was in the 18th army. He had left for the front line on some business’. He removed this paragraph from the 3rd edition of the book, when Brezhnev died. He also took his revenge over Nikita Khrushchev 21. He wrote in his book: ‘I remember well that when I came to the South-Western Front, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev arranged nice dinners’. Period. He was open and honest. I keep in touch with his daughter. Now my temper fails me. I read and reread the book with tears in my eyes. It’s next to unbearable! Such talent! Such pain! And who caused it? They were nothing; Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev or Brezhnev...

After I was released from the hospital I moved into a room in a communal apartment. It was provided to me by the plant where I worked before I went to the army. In 1946 I entered Moscow State University named after Lomonosov [editor’s note: M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, the best University in the Soviet Union, also well known abroad for its high level of education and research], The Faculty of History. I entered it immediately after the h hospital. I was fond of history and did well at the University. Being a party member I took an active part in the public life in University.

Once a terrible thing happened. It happened in 1947 during the period of struggle against cosmopolitism. I shared my thoughts with my friends saying that struggle against cosmopolites actually meant struggle against Jews. Somebody reported on me and this became the subject of discussion at the university party bureau meeting. The atmosphere at this meeting was very aggressive. This was something terrible! I was blamed that I did not understand the policy of the party. It’s hard to find words to describe this event! I did not agree to one single accusation of me or other people blamed of cosmopolitism. I spoke against any accusations. I held them to disgrace! I held the presidium to disgrace. This meeting was hard for me. Professor Cherniayev described this meeting in his book ‘My life and my time’. [the book was published in 1995 in the publishing house ‘International relations’ Moscow.] He also worked at the University and was also a veteran of the war, but I did not know him in person. He was at the meeting. During perestroika 22 he worked at the Central Committee of the Communist party, and now he works in the Gorbachev’s fund 23 [Editor’s note: Gorbachev’s fund is an International public fund established in 1992.] He dedicated a whole page to the problem of struggle against cosmopolitism at the University, and described how I opposed at the meeting. He also wrote: ‘Everyone kept silent’. How did Jews behave? They were mean! They were afraid of supporting me fearing to lose their jobs. A week later they were fired. I became passionate blaming them. They were saying ‘You don’t understand the policy of the party’ and I replied ‘You do not understand the policy of the party! You organize a campaign against Jews. You! If you are against this horrible and abusive movement, you stand up and say it instead of accusing me’. I don’t remember getting home. I thought ‘Where am I?’ Because nothing like this ever happened in my battalion at the front. It didn’t matter whether one was Russian, Ukrainian, Kazakh or Jew. What mattered was to be brave and honest! I never dealt with anything of this kind at the front. That was why I was stunned. I shivered with hatred and anger. But what was important I was not defending myself but I attacked them. I said ‘You are lying! It’s a lie from beginning to end!’. I said: ‘You are cowards! You know in your hearts that this is not true.’ Cherniayev was good. Fifty years later he reproduced it exactly as it happened. There was one thing he made a mistake about. He wrote ‘He either left or was fired from University.’ He did not know the truth. I did not quit the University or the party. I had many friends and acquaintances at the University. They were much older than me and treated me somewhat fatherly. I still don’t know who was my protector. I think it was Academician Nesmeyanov [Nesmeyanov Alexandr Nikolayevich (1899 - 1980), Soviet organic chemist, academician of the soviet Academy of Sciences, public activist, Hero of Socialist Labor], an outstanding chemistry scientist, who was rector of the State University at the time. He had a great authority in our country and in the world. He was a deputy of the Supreme Soviet. He was a decent and honest man. His follower was a lecturer at the Chemistry Faculty and secretary of the party committee of the University. I think the two of them saved me. Nesmeyanov must have taken the initiative. It worked so as if there had been no meeting whatsoever! I graduated from the University. What else is remarkable about this meeting is that all lecturers and students became aware of my Jewish identity. They could never guess it before since I looked very much like a Russian guy. I never experienced any opposition at the exams or when I defended my diploma. My examiners knew I was right, but they could not express it openly fearing for their job.

This was the first time I had doubts about Stalin’s innocence with regards to the events in the country. I knew Stalin was to blame. I came home very upset. I had Stalin’s portrait on my desk. When I was alone I threw it away.. It was a big color portrait. I believed him and so did millions of people, but this struggle against cosmopolitism shattered me! I decided we should not have hoped that he did not know what was happening. This was naïve. He knew and he did it with his own hands. So I bid farewell to the beloved leader.

During the period of the plot of doctors 24 in early 1953, when most Jews were fired from work, it had no impact on me. I was a post-graduate student at the university, but I felt this atmosphere, when patients stopped visiting Jewish doctors. Of course, this was abusive for me, a common and honest man. It only strengthened my opinion about Stalin.

When he died in March 1953 and the country was in the mourning, I felt relieved and even happy that he died. My eyes were open. I had no illusions though I tried to get to the Kolonny Hall to look at this dead man. This was the end of epoch. My friend, a Russian guy, who had the same attitude to the leader, and I went there. Thousands of people came to bid farewell to Stalin. The crowd crushed and many people died. We made our way there regardless. There were thousands of wreaths near the Kolonny Hall. We took our particular revenge on this demonstration of love to him. While we were trying to make our way through the crowd the horses of equestrian militia grabbed the leaves on our wreath, and we installed it among other wreaths at the front. (This was the only way to take our revenge on him. It was disgusting, this wreath, but we put it at the front. Nobody could reproach us for doing so. We just came to pay honors and who could blame us?

I finished my post-graduate studies, defended a doctor’s dissertation [Soviet/Russian doctorate degrees] 25 and went to work at Moscow Energy College. I was a lecturer at the department ‘History of the CPSU’. I worked there for 35 years. I still keep in touch with the college and my former students. They visit me at home. There was only one reason why I enjoyed my work. I invited my comrades, who marched the paths of the war. My students wrote reports about the war. I emphasized the war events in the history of the CPSU. I stepped aside from this policy and though my subject was History of the CPSU, I did not care. I knew but too well what kind of history this was. I resigned in 1991.

I met my wife Valentina Kisliakova at the Likhachev plant before the war. She also worked there. She waited for me through the war. We waited for one another. Valentina was born in Moscow in 1924. She was a good person. We got married in 1946. We registered our marriage and in the evening we had dinner with the family. Our first daughter Yelena was born in 1947. I called her Lenochka affectionately. My wife came from a Russian family, but there was not sign of anti-Semitism on her family. Her father’s name was Ivan Kisliakov and her mother’s name was Marpha Kisliakova. They had two daughters besides Valentina: Lidia and Claudia. They were workers. Valentina’s sisters worked at the turner’s unit. We keep in touch with them. My wife finished a secondary school and worked as an accountant at the plant. In 1956 our second daughter Olga was born. We were a loving family. My wife and I raised our beautiful daughters to become honest, hardworking and kind people. I was not religious and did not teach my daughters any Jewish traditions. Lena and Olia know they are Jews. My wounds had an impact on my health. I was ill for a long time after the war. My wife took care of me. I owe her my life. My wounds remind me of my health condition. My wife and I went to recreation homes and she forced me to keep a diet. I survived thanks to her care. Valentina created the atmosphere of love and respect in our family. It stayed with us after my wife died. My daughter Olia takes care about me now. She is doing it with the same dedication as my wife did. From our room we moved into a new apartment that we received from the Likhachev plant. Lena finished the College of Economics. The happy life of our family came to an end, when our beautiful daughter Lenochka died in 1962. She was just 25 years old. She had brain tumor. Our daughter’s death was a hard blow for my wife. She developed cancer and died prematurely in 1976. I think the grief after our daughter shortened my wife’s life. She was buried in the Vostriakovskoye cemetery. Olia finished the Law College. She works as a lawyer. She takes care of me and helps me with my pub. She has a son. He is my grandson. His name is Ivan Barashev. Vania studies in the College of foreign languages. Olia’s husband Alexandr Barashev is Russian. He is director of a small polygraphist enterprise.

I was happy about Israel in 1947 and about the fact that we voted for it at the United Nations Organization. However, it turned out that this ‘voting’ had a background. Stalin wanted to strengthen his positions in this area. I know only but too well how he ‘loved’ Jews. He did not care about Jews, he just wanted to have a base there. He thought this state was going to work for him. But the fact that our state and army supported Arabs in the war against this state was very sad for me, particularly that Israel took every effort to protect itself. Of course, this dishonest and hypocritical policy of the Soviet Union could only raise anger in me. I knew that our tanks were involved there and that they did not fight for the right. I was ashamed. Why send tanks there? Why arm the enemies of Israel? Who benefited from it?

I traveled to Israel in the early 1990s at the invitation of the veterans of the Great Patriotic War. The country struck and enamored me. An amazing garden created by loving people in the stone lifeless desert! It raises admiration. I’ve never considered moving there. My roots are here. I defended this land. My followers, friends, colleagues are here. My dear ones were buried here and this is where I’m bound to be. There was an incident at the airport. We were thoroughly searched at the airport. My companions went through the electronic detector, but when I stepped there it gave an alarm. The frontier men told me to put away everything metal. I emptied my pockets, but it did not help. The chief told me to go to an X-Ray room. I went there and took off my clothes. There were two doctors and an X-ray man in the room. When they X-rayed me, they were horrified. There were multiple splinters in my body. They let me go, shook hands with me and wished me good luck. On my way back there was the same shift. Their chief called them to attention and they saluted me.

I think that our country does not treat those who had marched the paths of the war with due care. They deserve more. They lived their life in terrible living conditions for decades. They were deprived of the very primary needs. They stood in lines and were abused and humiliated. And the Central Committee of the CPSU called this ‘modesty of a common Soviet person, veteran or invalid of the war.’ They made this formula. He cannot get an apartment and they tell him he is modest. How many of us are left?! What kind of attitude are we talking about now? Recently they increased our pension, but it was impossible to live on it! And it is the soldier who actually rescued the world from the Hitler’s plague. How should they have treated him? Germans and German veterans of the war live much better lives than those who won the victory! And the only reason is that our government has never thought about people. Never! All they care about is their career.

I received this apartment recently. The mayor of Moscow promised me to improve my living conditions and ordered his subordinates to find a better apartment for me. These officials kept leading me by my nose trying to make me agree to a new apartment in a new building in distant neighborhoods in Moscow. I’m an old and ill man and it would be difficult for me to commute that far away to do my public activities. It took a long time before they offered me this apartment in a quiet neighborhood in the very center of Moscow. Arkadiy Gaidar 26, a popular writer, lived here before the war and then his son Timur Gaidar lived. It was vacant before we moved in here. It looked quite abandoned and I felt like refusing it again, but my daughter thought different. We had to fix and refurbish this apartment which took a lot of money and effort, but I like it now. It’s spacious and my daughter made it very cozy. Everything would be well if it were not for my ailments. We are a close and loving family. I have everything I need. I receive a bigger pension being a veteran and invalid of the war, Hero of the Soviet Union.

The breakup of the USSR [1991] was sad for me. Like millions of other people who marched the roads of the war shedding our blood it hurt to know that we did this for the sake of the state that broke up Where was my consolation? I knew this would happen one way or another. It was built on the Stalin’s policy which was absurd in all respects. So, this feeling of being hurt was mixed with the sound feelings.

I was very negative about the perestroika. This had nothing to do with perestroika. There was a lot of chatting about it, but nobody, including Mikhail Gorbachev, knew what it was about. They went from one extreme to another until they came to a collapse instead of perestroika. These are different things. Our country has not matured for transition to capitalism. People need to be prepared. The majority of them have never heard about freedom of speech, press and entrepreneurship! How could a poor, badgered person understand this? They had to wait till the country matured enough for this transition. This was the only way to do it! We had nothing like this before. The country lived a bizarre life. From the scientific, technical and social standpoint the country was one of the last ones in the world. Our state focused on nuclear missiles and deference. It needs to be said that the people were working hard for it living in poverty and being paid 12 kopeck of each earned ruble. Nobody respected this country. The world and every honest value turned away from us. They turned away from us seeing that we had nothing in common with the values that we declared.

Of course, I identify myself as Jew. My parents were Jewish and I was born into a Jewish family. I’ve never kept the fact of my Jewishness a secret. We did not celebrate these holidays, but this was the life we lived, all in this country were raised atheists. There were other things concerning us besides religion.

I happen to take an active part in the Jewish life in Russia. I have been at the head of Council of the Jewish War Veterans and invalids [Moscow Council of the Jewish War Veterans: It was founded in 1988 by the Moscow municipal Jewish community. The main purpose of the organization is mutual assistance as well as unification of front-line Jews, collection and publishing of recollections about the war, and arranging meetings with the public and youth.] for 12 years. I’ve actually been at its head since the date it was established. There were rumors that Jews had never been at the front during the Great Patriotic War staying in the rear spread in Russia. They used to say ‘fought in Tashkent’ [Editor’s note: Tashkent is a town in Middle Asia; it was the town where many people evacuated during the Great patriotic War, including many Jewish families. Many people had an idea that all Jewish population was in evacuation rather than at the front and anti-Semites spoke about it in mocking tones]. This was a widely spread and abusive rumor. I think these rumors were spread by our ‘glorious’ bodies: NKVD 27, KGB 28. These were probably the first steps before of persecution of Jews in the late 1940s-early 1950s. I’ve always believed it was my duty to oppose those slanderers. It was not by hearsay that I knew about the war. Our Council was established to put an end to these rumors. After I retired I got involved in this life. I spoke out and suggested creating a Book of memory to list the names of all Jews who perished at the front during the Great Patriotic War. This was my initiative. I do believe this to be very significant and great thing to do. Ukraine and Byelorussia took up this idea and started publishing these books in their countries. They make use of our data and search for the names of their citizens who perished at the front during the Great Patriotic War. One cannot hold back tears reading the feedback from relatives in response to this book. This book is like a message from their children and fathers whom they had lost. I included the name of my brother Shimon Marianovskiy in the 2nd volume of this book. It’s very difficult to publish these books. Hard to find money to publish them. Besides, thousands and thousands of Jews have left the country. Some are in Australia, the others are in Canada or Israel. Where can we find them? And we need to find them all. They have documents with them, the death certificates. We need to include the names based on the archive documents. Our archives have no information about those who perished at the front during the Great Patriotic War. No such names. I’ve never dealt in the book publishing business. As I imagined, we would go to the archive and that will be it. Nothing of the kind! Firstly, our archives are just terrible. It’s humiliation of the dignity of the deceased. Meeting with the English or Americans I told them we have no book of memory. They could not believe it. ‘You mean, no book of memory?. I said ‘Right, we have no book of memory’. It’s hard to organize this. Now we’re finishing the 8th volume. There is a Grave of the Unknown Soldier in the center of Moscow, the symbol of the war and our victory. This is where the survivors of the war, members of the government and the visiting VIP’s come to honor the memory of those who paid their lives for the victory, but this is very wrong! The memory of each person who gave his or her life, the most valuable thing that they had, must be cherished in the hearts of citizens of the country they protected.

Glossary: