Mira Markovna Mlotok

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Orlikova

Date of interview: March 2002

I am Mira Markovna Mlotok. I was born in 1920, on December 5, in the town of Khorol. Khorol was a small Jewish town in Poltava province, where everyone knew each other. My father’s father was a rabbi there. His name was Moses. His family was large: three sons and two daughters. My grandmother was a housewife. Their family was noble. All children - boys went to yeshiva and all girls went to Jewish school.

I don’t remember my grandfather and his house very much. I remember what he wore when he went to the synagogue: a taleth, a yarmulke, and a small box on his head, I forgot its name. [in these small box put convolute sheets of paper , to which were written prayers, this is identified tefilin]. Grandmother was a very quiet and gentle woman. But I did not spend much time with them because we lived in another city. They were very religious. They always prayed and always kept Sabbath. All their children spoke Yiddish very well – they spoke Yiddish at home. Then all their children went into revolution and became atheists. Their parents did not oppose them because they were wise people and understood that the new time had come. Their eldest son, Zinoviy, was born in 1891. He was a Communist Party worker in Lubny. When the Second World War broke out he went to fight. He was heavily wounded and died in 1946 from diseases in Belaya Tserkov. His brother, Abraham, was born in 1895. He also was a Communist. He died in Chernovtsy in 1948 from some diseases. My father’s favorite sister Katya (Kitusya) was born in 1897. She married a big Party leader Alexandrov. He was arrested in 1937. Her life was very hard. She died in Chernovtsy in 1985. The youngest sister Anya was born in 1898, lived in Leningrad for many years and died in 1945.

I remember the big room of grandfather’s house. They had carved furniture, a huge sideboard with carved birds, a big table with round legs, around which the whole family sat. Grandfather sat at the head of the table and everyone looked into his eyes. When he lifted up his cup the day turned into a holiday. Their big carved bookcase had a lot of books. And they had a small violin. One of the children played violin, but I don’t remember who. All of them sang beautifully Zmirot when came guests , in holidays on eve Sabbath. Their family was a friendly and talented one.

I was very young when we moved, but I remember people singing all the time, having smiles all the time, drinking red wine. I remember small silver wineglasses. Grandmother gave everyone something sweet, strudels with apple, nuts and jam.

My mother’s name was Rosa Moiseyevna Kashtan. She was born also in Khorol, in the family of shoichet, meat-cutter. Both families (of my father and mother) knew each other very well. Mother graduated from Midwifery School in Kremenchug. She was interested in revolutionary ideas. When Denikin’s gang was around, she carried a white bag with red cross and distributed revolutionary leaflets. She risked her life, but that bag saved her; she hid her revolutionary propaganda in it. At that time if a person wanted to join the Communist Party he had to provide recommendation of more experienced and trusted party members. So, my mother gave such a recommendation for him. They met before the Revolution. They had common views.

Her mother was an ordinary woman, without education, but very smart. When Denikin’s soldiers came to kill the Jews she cut her feather bed and when the soldiers opened the door the feathers flew around, so they had to leave. Thus she rescued her whole family.

The family of my mother’s parents was large. They had three sons. The eldest was Sholom, then David and Saul. They all finished yeshivas and moved to big cities early – two went to Petersburg and one to Kiev. They worked a lot and did any kind of work only for the right to listen to lectures in the medical university. They took and passed examinations without attending all the classes. Saul then worked in Kharkov as the chief doctor of a polyclinic of workers. David was sent to the Donetsk coal basin to miners and was a doctor there. Then David moved to Kiev and his whole family (he, his wife and son) were killed in Babiy Yar. Sholom, the eldest, went to Pavlodar during the war (they were evacuated) and stayed there with his family. He died there in 1955. Saul had a son, Boris, who graduated form a technical university in Kharkov. When the war broke out he went to fight as a volunteer and was killed somewhere in Ukraine.

My mother had two sisters. Tsipa died early. Tsipa had one son, Aron. His father, Tsipa’s husband, was also a shoichet. The Soviet power denied the rights of citizenship and the right to vote to him because shoichet is a profession related to the synagogue, while the Soviet power declared religion outside the law. Their son wanted to study very much. After Tsipa’s death in 1932 Aron came to us, to Lubny, from Khorol by train without a ticket. So, we took him to live with us. He studied at the workers’ department and was an excellent student. In fact, he knew only Yiddish because they spoke only Yiddish at home, but he managed to graduate from the Chemical Technology Institute in Kharkov. Then he volunteered to fight during the war and did not return from it.

The eldest sister, Leah, married a man ill with tuberculoses. He took her out of Khorol into a village in Poltava region. He was Jewish and a talented man. She bore seven children from her ill husband. He soon died. She had no profession, so she learned to sew and her children worked the soil since early age; her boys also fished and thus they did not starve to death, but they were very poor. They had only one pair of shoes for all the children, so they went to school in turns. The boys walked barefoot even in winter. But they survived. The girls, Rosa and Sonya were put into basement to hide from Denikin soldiers, so they had problems with their legs and feet for the rest of their lives. Sonya worked as a doctor and Rosa – as an engineer in Kharkov. Despite all the hardships they survived. A son of Leah was an electrician engineer who worked at Dneprovsky NPP. Eida was the eldest of Leah’s girls. She lived in Lubny and worked as a nurse at the spirit factory. Her mother, Leah, being old lived with her. The eldest son, Chaim Meyerovich Krasik, worked in civil aviation in technical provision. He knew personally many famous pilots, and they respected him for “Sholom-Aleichem” types of jokes. In 1937 he was arrested on suspicion of espionage. He had to stay in horrible conditions. I was very young then. People at that time were afraid to intercede for somebody’s release because it was dangerous. So my mother said, “I can’t write him, but you a child, you can”. So I sent letters and parcels to Chaim as if from myself. When he worked at wood throw he froze so that he was thought to be dead, but the doctor noticed he was alive at the last minute. Later he worked with Ostap Vishnya (famous Ukrainian humorist) and Ostap Vishnya liked him and his humor too. When Chaim was released he settled in Moscow and sold tickets to theaters. He had no family.

Leah died in 1942 when the Germans came to Lubny. They also had a place like Kiev’s Babiy Yar – a common Jewish grave. She was very old and could not walk, so the Germans did not want to carry her to that grave and left her in her flat. Her neighbor, a Ukrainian man, took care of her until she died. He buried her in his backyard. Leah’s son, Iosif, stayed in underground of the Party and was a guerilla. His neighbor betrayed him. The Germans surrounded his house, took him out, called all the residents of the village he lived in, put a board on his chest saying “kike-guerilla” and burned him alive. His son was young at the time, 13 years old. He crossed the front line and found himself at an airdrome. There he said, “I came to take revenge for my father”. After the war he was sent to an aircraft school. His name was Boris Krasik. So, he remained in aviation for the rest of his life.

My father, Mark Moiseyevich Mlotok, was born in 1893. He finished yeshiva – 4 classes. He had no other education. He educated himself. He read a lot. He also played piano. He was a very gentle man, but kept strict discipline. He did not go to university but got involved in politics. There were many revolutionary clubs at the time, so he got engaged with these activities and under the Soviet power he went to work in the Extraordinary Commission to Fight Counterrevolutionaries. He was in control of money and values confiscating from the rich. For many years he worked at the State Security Committee. He started his career in Cherkassy. There my father and mother got married. It was certainly not a traditional Jewish wedding, but a new, communistic, wedding, with no ritual, no chupah, but with simple registration – such was the fashion then.

Father was sent to different cities of Ukraine and he fulfilled the Party’s orders there. He liked that work very much. He was an honest man: while other people got rich in similar positions, my father gave every penny to the state. When he had a lot of experience in that work, he came to Kiev and was highly appreciated by the People’s Commissionaire of the Interior of Ukraine. (Many innocent people were killed because of him. In 1937 he was arrested and shot too). My father was made chief of the personnel department, which was a very prestigious office. In 1937 many people were arrested and my father was doomed to arrest too. But he was sent to the north instead. He was appointed the chief of the camp of political prisoners in Archangelsk, which was in the north with mosquitoes and permafrost. Prisoners of his camp floated logs there. It was a demotion. He did not get any more military ranks in his life, just a mayor. But praise God even for this, at least he was left alive. He worked in the GULAG system, then he was sent to Siberia – Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk, where he was the chief of camps again. Then he was sent to Karelia-Finland, where he was the chief of the construction of a hydrosystem.

Back when father was going from city to city he had an affair with another woman. Her name was Gusta. She was an active Komsomol member and a beautiful Jewish woman. We saw father very seldom, only when he came to Lubny. Officially parents are not divorced, father simply has left not lives with us. My mother did not want to forgive him and cursed Gusta She never had any children. She died in 1938 from cancer. My mother took me and returned to Poltava region, to Lubny. She worked as a paramedic in a children’s hospital and in ambulance. We lived in a house for medical workers. My mother worked a lot because she had to provide for herself and me. We lived poorly. Mother sewed me clothes from her old clothes “to keep me in a decent appearance” as she said. Every time she had vacation we went to her brother in Kiev. We went to Opera Theater and the Zoo. When we came to Kiev for the first time I was 7-8 years old. I remember we went to the Zoo and looked at Kreschatik, the main street of Kiev, and at the Botanic Garden. My mother only had two weeks of vacation and in that time we had to go everywhere, see everything and buy everything we needed. For me, Kiev was a fairytale. I dreamed of studying here.

Lubny was a good green town at the time. There were a lot of schools, a medical college, a teachers’ institute and other institutions of learning, as well as a few plants. There were buses, but no street cars. I never felt anti-Semitism, nobody called me a “kike”. The atmosphere was absolutely different from that after the war.

I remember the famine in 1933 very well. Only due to the wisdom of my mother, who sowed the seeds of pumpkin, we survived. We ate so many pumpkins that we became yellow. But we survived. We also ate “makukha” cakes – leftovers pressed together, of black color. When we chewed on them we did not feel so hungry. But in order to get those “cakes” we had to stand in lines for a long time. My mother was very kind and if she received 200 grams of bread but had to go see some patients, she took this bread to her patients and told me that we could eat pumpkin again. Mother’s brother, doctor David Kashtan, worked in Donetsk coal basin, where miners received more foods than others, so he sent us parcels of foods. So, I know what it was like living in 1933 very well. My father did not really help us.

Everyone suffered then. I was very thin. But I was always joyful. We just had to hang on and survive. A year later, in 1934, life became better.

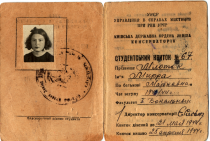

I was certainly a pioneer. To join pioneers was a great celebration, at the Pioneers’ Palace. I wore the red pioneer tie with great pride. And I loved singing pioneer songs. I was a very active girl. I had a lot of friends. I laughed a lot. I remember mother sewed me a costume of gauze and I danced a Hungarian dance. The time was hard, but I was singing all the time, and people said I had a good voice – lyrical-coloratura soprano. I sang at the pioneers’ club and was invited to sing at different celebrations. When I was 14 years old there was the first children’s musical festival in Ukraine and I was noticed. I was sent to Kharkov. There were a lot of children from different cities. We stayed at the “International” hotel, downtown. All the concerts took place in “Berezil” theater. The jury decided that Mira Mlotok should take singing classes for sure. They made pictures of me and wrote an article about me and a boy who played violin, Dusya Solovyev. But my mother did not want me to leave after the seventh grade. She said, “You are still a child. Finish ten classes general first, and then do whatever you want”. When I finished the tenth grade I went to Kiev. I passed several exams and entered the Gliyer Musical College. First, when I came to Kiev, I stayed with my mother’s brother, uncle Sholom. But they had a large family and I had to sleep beside their wardrobe on a camp bed. My mother sent parcels to the whole family in order to support me. My relatives treated me very well but I still felt that it was hard for them to have another person living there; besides, they imposed their will on me, while I wanted to be independent.

When my father learned that I entered musical college without anybody’s help, he found me and he said he liked me very much. He realized his mistake and decided to help me become a real urban girl. He took me to the central supermarket and bought me a lot of clothes and shoes. I felt equal to other students of my college.

Father and the woman he lived with, Gusta, had a big flat downtown, with good furniture; the flat was very rich. They offered me to stay with them, but I refused. A daughter should always support her mother. I loved my mother very much and did not want to betray her. My father was a kind man, very gentle and honest. But he could easily be influenced. That woman, Gusta, could cause him to forget everything, including his family. But when she died, father came back from Siberia, where he worked, and asked my mother to reconcile with him. She agreed to go and live and work with him in Siberia. When my parents left, I no longer stayed with my uncle, but rented a room together with a relative from Khorol. She studied in university. We liked living together. We left the house every morning, I walked with her to the university and then went on to conservatory. We ate together and bought foods together. We had our companies together – my friends and hers.

I had to learn a lot of things at the college: solfeggio, piano, history of Russian music, harmony, history of Ukrainian music, history of west-European music, dances, and actor skills. It was very interesting to study. All outstanding musicians of Kiev taught in the concervatory and in my college. Studies in the college gave us the right to enter conservatory.

I had a lot of admirers. But I never treated them seriously because they all wanted to marry me. And I did not need that. I wanted to study. I had several marriage propositions. One man even went to Lubny to ask my mother for my hand. It was conductor, Yakov Fridman, a Jew. He worked in Nikolayev. But my mother said, “No way! You are 10 years older than her! Why do you need such a young girl?” So, that was my first marriage proposal.

But when I met my husband… it was love with the first sight. That’s how it happened. I had an academic concert at the college. After the concert I went to a tailor, to try something on. He was there. My God… He was wearing a naval uniform; he was cheerful and full of charm – you could not help loving him. That tailor was his uncle. His name was Yefim Nusimovich Sapozhnikov. He went to see me off that day and did not let me go. The next day he brought me flowers. The landlady of the room I was renting was jealous because she liked me and wanted her son to marry me. She was Jewish, Nomi Iosifovna, and she wanted her son to marry a Jewish girl. But I liked Fima so much! He was an interesting young man and he wore nice clothes. He finished the Kiev Polytechnic Institute and designed a ship. He was sent to the navy, very far away, to Vladivostok. By the time we met he had been working there for a year or two and came to Kiev on vacation. We met in the middle of June 1941, a few days before the war.

Fima came to see me every day with flowers. We did not know each other for too long, but it was love with the first sight. I was horrified, I did not know what to do, I could not get hold of my parents (there was no communications with Karelia then). He proposed to me. And I thought, “Why not?” So we went to the registration office. People looked at us with surprise: people scatter away from bombings and we are walking with flowers to register our marriage. I don’t even remember what I was wearing. After the registration we went to his parents. His father, Nus Alterovich Sapozhnikov, was a Red guerilla during the Civil War. He had a surgery before the war and his kidney was removed. He worked as a manager in Lavra (the largest and the most beautiful Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine). His mother was Freida Borukhovna Linetskaya. She was a housewife. For a long time we had no intimate relationship because I continued to stay at my room, and his parents were going to evacuate.

We got on a barge because it was impossible to get on a train or ship. We had to flee by any transportation because the Germans were close. I did not know about the threat to the Jews at the time, but I was scared. Fima’s parents evacuated. And I was waiting for a message from my parents, so I asked Fima to wait with me. We could hardly get on that barge. There were logs and a small room for the captain. The barge was overcrowded with people. All people sat on the logs, close to one another. It was very scary. We could not move. But we were rescuing our lives. When we reached Kremenchug, there was a heavy bombing raid. As it turned out, somebody was sitting on this barge with a flashlight and pointed the Germans to the barge. My Fima noticed this. When the bombing began the captain landed and all people went to the shore. Fima went to catch the one who pointed the Germans to us. I said, “How will you find me afterwards?” He said, “You will start singing and I will find you”. My husband caught that man and brought him to the authorities in Dnepropetrovsk afterwards. They said he landed on parachute to us. I began to sing a Ukrainian song and Fima found me by my voice and led all other people back to the barge. We went on. In Dnepropetrovsk we found Fima’s cousin. All Fima’s relatives were gathered there – parents and their three-year-old grandson Boris (the son of Fima’s brother). They met us nicely but we all had to go on. My husband had to return to his place of service – Far East. I could not go there without a visa. So, he went alone. All trains were overcrowded. He jumped on the steps of some freight train and told me, “Don’t worry, we will keep in touch”. We decided that all of his relatives will keep in touch through him and that he would send a telegram to my parents. There was shooting every day. Fire-bombs exploded at night and nights were like days. The Germans were approaching Dnepropetrovsk. I was left with Fima’s parents. Evacuation from Dnepropetrovsk began. But we were not on the list and nobody wanted to take us. There was no way out. It was horrible. So, we went to the train station and got on some freight train – just so that we would go somewhere. We were taken to Northern Caucasus. It was steppe. It was a German colony that worked with grapes. The Germans were very nice to us, shared beds and foods. Grandmother, Frida Borisovna, Fima’s mother, spoke Yiddish better than Russian, and the Germans understood her somehow. We went to work with them, gathered grapes. Everything went well and we fulfilled their plan, but suddenly it was announced that within one night all Germans had to leave that place. They could not take anything with them. It was Stalin’s deportation of the Germans over the Urals mountains as “Hitler’s assistants”. It was horrible. Only those who were evacuated to these places remained, but not many.

As soon as the Germans left, the Nazi parachutists came. We even heard their speech. We were horrified. But in 30 minutes we were put on a truck and taken to Makhachkala by the Soviet authorities. In Makhachkala we were put on a small boat and taken across the Caspian Sea to Middle Asia. There were many evacuated people there. I remember the sea was stormy. We were taken to Krasnovodsk by sea. From there we went to Tashkent. We found ourselves on the train station. We had no documents that we were evacuated. And in order to get food at the train station we needed documents. As a matter of great favor we were given a glass of kumys (goat milk) each and a piece of bread. While we were sitting on our bags in the street a noble Uzbek man, whom we did not know, came up to us and gave us some food. We wanted to get to the Ural mountains. Before our departure from Dnepropetrovsk I received the address of the place where my parents had moved; Fima let me know that address. So, we went to that place. We were put on a train wagon that carried prisoners before us. There were so many lice that when we reached our destination we did not enter the house. My father threw away all of our clothes, while my mother brought us everything she could find for us to wear, including underwear. So, only when we were clean we entered the house. It was in the town of Perm, which was then Molotov. My father worked there. Outside Molotov there was village Ioranchi with a camp for prisoners. My father was the chief of that camp. My father had wonderful organizational skills.

Most of prisoners were put in jail for political reasons – on suspicion of espionage, anti-Soviet activities, bringing harm to the nation. All of them were certainly absolutely innocent, but it was such a time when anyone could get in jail so that others would get scared. These people were of different professions. There were many medics, intellectuals, artists, actors, authors. I remember the name of one doctor, Simon, from Moscow. He was a quiet Jew, a noble man. My father made him chief of the medical unit of the camp. He had an assistant – a Jewish woman, Genya. There was a shoe shop in the camp, laundry, and other workshops. There was an amateur theater and prisoners performed wonderful concerts. Some prisoners were wonderful actors, former soloists of the best theaters of the Soviet Union. My father understood that these people were innocent, because many of our relatives suffered too. But he was unable to change the policy; it did not depend on him. However, he was a man of discipline, who had full trust in the Communist Party.

As a real member of the Security Committee since 1920 he had a double name. His party nickname was Davydov. In his documents he was Mlotok-Davydov.

We lived not far from the camp. We lived in a one-floor wooden house. We had a stove that we heated with woods and cooked on it. It was hard for my mother, a woman who never did that before. Then Kitusya, father’s sister with two children came to us. They were very thin, like dystrophic patients, and the girl had rash on her hands. But my mother knew how to cure that. They were behind their class at school. My mother sat with them and helped them study so that they would not lose that school year. She cooked at the same time. And she managed – they became normal children.

I never went to the territory of the camp. People could get there only by passes. I could never go there. I was very sorry for these miserable people. I never talked to the prisoners myself, but I heard stories about them from my father. In general, we did not go anywhere if we did not have to. Kitusya began to work as a secretary in a technical school. Father helped her get a room not far from us. Thus they survived that hard time and we certainly helped them. Sapozhnikovs, the family of my husband, also lived with us in the beginning, but then father helped them get a room too. But very soon Fima’s father died. He got infected at the barber’s and he had blood poisoning. He was only 54 years old. He was a very good man, an extremely kind man. He called me his daughter. My husband’s wife and a child remained. Fima sent them his documents which allowed them to get some money as the family of an officer, and thus they survived those hard times.

I did not spend a long time in Perm. In winter I went to Sverdlovsk springtime 1942. It was a very snowy winter. I could not cross the street before it was cleansed from snow. I learned that the Kiev Conservatoire had been evacuated to Sverdlovsk. The teachers recognized me and treated me well. I rented a part of a room. We studied in the premises of the Sverdlovsk Conservatoire. It was a wonderful building downtown, on Lenin Street. We had a life full of music. Famous pianists, actors, singers and musicians came there. We, students, performed in hospitals. We had to smile there. We were looking at those wounded soldiers wrapped in bandages, our souls cried out, but we had to sing and smile to them. Especially if we met somebody from Ukraine, we became like relatives to one another and tried to do whatever that other person desired from you. The military who formed tank divisions in Sverdlovsk came together in the Officers’ House. We performed a concert to them as well. And the next morning, we went to see them off, and when we were at the train station; it was very cold and frosty and we should not have sung, but we sang anyway. There were different people, including the Jews. But there was no anti-Semitism. And many Jewish boys were killed. When Kiev was liberated we had classes. We heard on the radio that Kiev was liberated. Both students and teachers hugged and kissed each other, jumping high. It was such a joy that I can’t even describe it. We were taken to Kiev. We were all happy. We went to see around the city. Kreschatik was in ruins. The captured Germans were clearing out the ruins. Some people got so mad at them that they spat at them right in the street. Kreschatik had been such a beautiful street, and they made it lie in ruins!

I kept up a correspondence with my husband. Every time I entered the conservatoire, a letter from him expected me. He continued to serve in the Far East.

When the Conservatoire returned to Kiev I was living in a dormitory. There were no windows after the war; all windows were blocked with boards. It was very cold; we had to play piano in gloves. We died from cold and hunger. There was also a band of gangsters at the time called “Black Cat”. They killed and robbed everyone. After every murder or robbing they left a sigh – a black cat. They came to us as well, but then saw that they could not take anything from us, students, and left. They did not each touch us. We shook from fear and cold. My friend Sofa and I slept together in one bed and covered ourselves with our two coats over the blanket. When we had to practice singing we went to the Conservatoire because they had some heating there. It was a horrible time.

My husband and I met in Moscow, accidentally. I was going to my parents to spend vacation there (my father remained to work in the Urals) from Kiev. I had to punch a ticket. I came to the student cashier, and saw him standing there. Moscow is so big, and we bumped into each other four and a half years after seeing each other for the last time. He was given a leave and he was going to find me. First we did not recognize each other. We had not had too much time together. He was smoking a cigarette and when he recognized me he dropped it. “Mirochka?” he asked. I said, “Yes”. He said, “We will never part again”. So, we went to my parents together. But first we spent two wonderful days in Moscow. It was 1945 – the war ended!

Can you imagine the joy my parents had when they saw us together? They liked him very much, because he was very cheerful, full of charm and kind. But I could not go to his base with him again. I was waiting for a special visa and then I went to him. At that time I was already pregnant with Lora when he left. But my pregnancy was not visible yet. In Vladivostok I even sang in a philharmonic society. Fima worked as the chief constructor at a shipbuilding works with huge naval ships. He was very talented. And his bosses characterized him in an excellent way. In our flat we had nothing, only an iron bed just like in dormitories, a small bedside table and a box in which I brought my belongings, which we used as a chair. But we had such a wonderful time together that we did not notice how empty it was in the flat. His friends and colleagues came over and we were happy to be alive, to see one another. We did not need anything else! I went to sing and Fima went to try his underwater mines. There was a custom that when sailors go into the sea they had to throw something away in order to get back safely. I did not know it before. Once, Fima came back with only one glove. I asked, “Where is another one?” He answered, “See, I am alive, my trials went well – I had to throw something away”. Another time he threw away his slipper.

I went to Molotov, to my parents when it was due time for me to deliver a child. My father occupied a very high office – deputy director of the main department of camps of prisoners (GULAG) in Molotov region. My husband accompanied me. Our tickets cost very much, so we were advised to “justify the means”. It meant that we had to do some commercial operation. But Fima and I were such bad “businessmen” that we lost rather than benefited from it. We bought a small barrel and fish to smear it; but there probably was a hole in the barrel because the fish got stinky and we were happy to get rid of it.

My parents had a big flat downtown. They welcomed me nicely. My older daughter, Lora, was born in 1946. The first delivery is always hard. But my beauty was born! She cried a lot. My parents would rock her all night long, but she was crying and crying.

In Vladivostok my husband submitted requests to be transferred to reserve, and finally he was allowed to. He had a choice: to live in Port-Arthur, Dantzig, Keningsberg, or Kiev. He certainly chose Kiev. We moved here and he was given a wok at a shipbuilding plant. This plant was located in Podol, near Dnepr. It used to be named after Stalin. Fima restored the diesel workshop of that plant. He stayed there day and night. I brought him meals there because he had no time to go home and eat, even though we lived nearby. I went back to the Conservatoire. There was no transportation, so I had to walk up the Voznesensky street from Podol. Lora was still young and I nursed her.

The flat of Fima’s parents had burned down. We lived in the dormitory of the plant. It was a big house; 12 neighbors had one kitchen. They treated me nicely because I had a baby. First we were given one room, then two. Before Stalin’s death all Jews were fired form such organizations as GULAG. My father retired on pension, then in 1949, my parents moved from Molotov to live with us. We had different neighbors. One was anti-Semite. When my father died and she saw all his awards she said, “Those kikes bought medals with money”. Certainly this was not truth and all this understood. But general mood was against Jews and we could not do nothing, therefore that protect us was certain, but live was necessary. Then my husband received a separate flat in Obolonskaya Street, in Podol. In 1951 my second daughter Nata was born.

The family was large: Fima’s mother, my parents, my husband and I and two children – seven people. Praise God, we had no quarrels. Fima’s mother could not see well. My mother would sit and read out loud and she would listen. They became very good friends. Then my father got very ill. He had three heart attacks and also he had stenocardia, so he could not breathe well. He smoked a lot and was very nervous and he died in 1954. He was buried with honors. He was on the list of honored Communists. He did not spend a lot of time in Kiev; here he spent time chiefly in the hospitals. He died at the age of 62 in 1954. In 1962 my mother died at the age of 67.

I did not work. My husband had a lot of important work. So, I did not sing. We had a very friendly family. Fima loved me very much. He said if he had another life he would have married me anyway.

I speak Yiddish but I cannot read it or write in it. My girls understood Yiddish because their grandmother, Fima’s mother, often spoke to me in Yiddish. When we had to conceal something from our kids my husband and I also spoke Yiddish. We cooked Jewish meals; stuffed fish, hen with prune, salad with cheese and garlic, bean with onion, we make motzebrai from matzos, stuffed fish, and Jewish roast meat, and others at home and bought matzos in the synagogue every year. We keep post in Yom Kippur and celebrated other holidays. Light candles at Saturdays, in Pesakh, go to synagogue and do not eat bread, only matzos. I considered grandmother’s age, and when she returned from synagogue I always knew what to cook for her. I tried to please her all the time and she was pleased. She could not see well, she had three eye surgeries. I treated her in such a way that some of our neighbors thought she was my mother. I still like Jewish dishes.

We certainly felt anti-Semitism, especially Fima. His boss was an illiterate Ukrainian man, who could only sign all the technical documents that Fima made. Fima never was a chief because he was a Jew. When he went to Czechoslovakia, we were all surprised that he was allowed to go outside this country.

First Lora and then Nata followed their father’s steps – they graduated from the shipbuilding Institute, economic department.

Lora got married at an early age. Her son Yura was born. In order to help my daughter we took full care of our grandson. Today Yura is 34 years old. He is a very good boy. He is a businessman. Lora’s family life failed – she divorced. Then she got married again and gave birth to a daughter – Sveta. Today, Sveta is 18 years old. She lives in Jerusalem, Israel. She is already married. Nata moved to live abroad. Many young people were moving and she also decided to go to America. At those times it was considered treachery. She concealed from us the fact that she decided to leave. It happened in 1979, and Nata was afraid that her father would not let her go. Fima was a Communist Party member and occupied a high office. She and her husband took English classes in secret, while Lora and I babysat her child, Gena, at home. He was less than two years old then.

I learned about her plans accidentally when they were on the go. I had to prepare Fima to give them permission. He loved her very much, as well as his grandson. He told me, “My God, I will never see her again! But if she wants to go, I can’t hinder her, let them go”. He was ill at that time – he had a bad case of adenoma. So, he gave Nata permission. Soon after that he was summoned to the district committee of the Communist Party and was ordered to return his party ticket. He threw his ticket into their faces. What else could he do? He cried as a child. He could not even see them off because he was ill. But in his heart he felt that he would never see her again. Later we got a postcard from Italy: “How wonderful that I was born Jewish! I could finally see the beauty of the world!»

Fima got into hospital. I spent 4.5 months there with him. Lora and I raised him up. He lived ten more years. He retired and got very interested in drawing. Our whole flat was full of his pictures. He also played chess very well. He missed Nata very much. Fima died in 1990. He wanted to go see our daughter in America; he was even willing to cover his travel expenses, but Nata’s husband, Mark Ostrovsky, did not want to send him invitation, beside us never come in well relations. Nata loved him and did everything he said. But when Fima died she sent me an invitation. I went to see her. I had not seen her and her child for 14 years! But I did not stay there for a long time; I was drawn home. They would go to work and I would stay home all day long, with their dog. I could not talk to anyone; even their dog did not understand Russian. Nata’s son is graduating from college this year. In summer they are planning to come and see us. She wants to show him where he was born, his motherland.

Lora is working in “Khesed”, which is a Jewish charity organization. She works as a curator. She takes care of the elderly Jews. I am very proud of her and very pleased with what she is doing. She brings me Jewish press to read, and I read all papers and magazines. I always look forward to novelties. I am very interested in them. I watch closely all developments in Israel. Unfortunately, I’ve never been there: first I was not allowed, then I could not afford myself. I am a great patriot. If I were younger, I would go there, but unfortunately my years have passed. Day by day is passing. I’m scared to go there now. But I had such plans when I was younger, to be honest. But now I just need to live the rest of my life – I am 81 years old already.