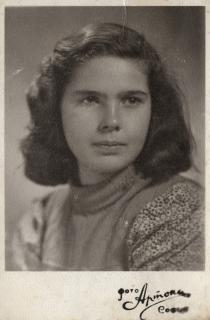

Milka Samuel Ilieva

Ruse

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Patricia Nikolova

Date of interview: September 2004

Milka Samuel Ilieva is a cordial, sociable and calm person. Her restless spirit, however, was a witness to stormy and contradictory political and life turning events. Her sense of humor as well as her natural kindness have saved her many times from the despair that awaited her at every single step. So many nuances of the Jewish character and Jewish spirit are reflected in her life story, that it looks more like a screenplay than real life. That’s why her words are wise, precise and sincere. Her jokes keep hidden a lot of unarticulated grief and hidden bitterness.

I’m a descendant of a Jewish family from the Sephardi 1 branch that came from Spain more than five centuries ago. As is well known, most of the Jews expelled by the Spanish Queen Isabella in the 15th century settled on the Balkan Peninsula 2. My ancestors had a similar fate. Unfortunately, I know almost nothing about my grandparents, because they died before I was born. And what’s more, I made the mistake of not asking my parents for details about them. However, I know that my parents, Ventura Samuel Mashiakh and Samuel Moshe Mashiakh, were born in Nis, Macedonia [Editor’s note: Nis is in today’s Serbia and Montenegro.]. They met in Nis and then the two families, Shamli and Mashiakh, decided to move together to Sofia. So it was in the Bulgarian capital that my parents got married, in 1910.

We were a merry big family of ten members. Eight of us were only the kids: five sisters and three brothers. Mois was the first, born in 1911, followed by Ester in 1913, then Albert in 1915, Nissim in 1917, Sara in 1920, Venezia in 1922, Jina in 1925 and lastly I was born in 1928. We lived poorly, I would say, but our life was very spiritual and amusing despite this. What’s for sure is that we never lacked a sense of humor.

My father was very religious, but we, the kids, didn’t manage to preserve this religious spirit. Our life made us atheists. Maybe this was because we lived in poverty and everyone in the family had to start working at a very early age. Our life was hard; we saw all the injustice around us and that provoked a strong social sense in us rather than a religious one. But at least when we were young we observed all the Jewish holidays with my father. He used to tell us a lot about them. We strictly observed the kashrut at home on Pesach, and on the eve of this great holiday, all of us used to help my mother with the big cleaning up. [Editor’s note: She probably means that they had a traditional kosher meal for Pesach and maybe other holidays too but didn’t observe the ritual rules for the rest of the year.] Nobody was allowed to bring bread home during Pesach. As a matter of fact, there were no religious books in Ivrit [Hebrew] at home. I have also no information on whether my father was a member of a Zionist organization, although he must have been a convinced Zionist. What’s more important, the Jewish rituals observed on high Jewish holidays made our family really united.

I’ll never forget how we used to celebrate Purim. There was a very nice song for Purim of whose origin I know nothing. The specific point about it was that every new stanza began with a letter in accordance with the order of the Hebrew alphabet. My sister Sara sang it marvelously. On Purim my father would always tell her, ‘Sarika, please, kerida… [‘dear’ in Ladino] and she would start singing. The feeling was remarkable. I remember visiting Sara in her kibbutz during my last journey to Israel in 1990. I cannot recall the name of her kibbutz. Her job was to patch up clothes on a machine and the people loved her. So we, the three sisters, went to see her. I remember she lived in a small neat room; she also had a toilet and office in her room. Well, I went to her and asked her, ‘Sister, please, sing the first stanza of our favorite Purim song.’ She was 80 then. When she started singing something happened to me. I rushed out of the room in tears; I just couldn’t stop crying. I remember we were a very warm, united, extraordinary family.

After my mother gave birth to me, she got paralyzed from rheumatism. She sat on a chair and was no longer able to stand up. Then they decided to ‘sell me’ to some rich relatives of my mother, her cousins. In those days it was routine for the poor and fertile Jewish families to give one of their children, usually the youngest one, to a relative childless family. In exchange, the well-off family offered financial support to the poor one. As far as I know they were trading with clothes. Since my mother was paralyzed, a woman had to come to wash and swaddle me. My brother Nisso [Nissim] helped her do that. He was eleven years old then. Once he came back from school and saw a car in front of the house. Let me mention that it was 1928. Automobiles weren’t a usual thing to see even in the capital. Right at this moment, they were preparing the baby’s napkins at home to give me to these people.

My brother entered and shouted, ‘Mother! What’s that car doing here?’ Are you going to separate us? Don’t give Milka away! I’ll fill my pockets with pebbles and I’ll break this car’s windows, mind you…’ And he started filling his pockets with pebbles. And it was exactly what my mother had waited for, ‘We will not give her, go away, that’s it!’ That’s how she abandoned her decision.

Another curious fact is that all the children from my family studied in Bulgarian schools. It was only me who studied in the Jewish school, because my parents had decided firmly to send me to Israel, where my father’s sister planned to adopt me. It was a normal thing in the Jewish families then; if some of the relatives are childless, the next of kin, who have many children, give one of theirs to them so that the childless family may bring it up as their own. I was the youngest and because of that, they decided to give me to my father’s sister. This never happened, though.

My maternal grandparents were Avram Shamli, and I don’t know my grandmother’s name. I know really nothing about them. Most probably, they were poor. My paternal grandparents, however, Moshe and Venezia Mashiakh were well off. I know that they set up a sugar processing plant when they emigrated to what was then Palestine in 1930. They produced chocolate sweets there. That’s all I know about them.

My mother was something like a martyr for me. She took great care of us, but we were eight children in the family. Although she was illiterate she always knew how to be kind to us, how to bring us up, what to feed us, so that we would be healthy. She was strict about cleanliness despite the poverty in which we lived. It was easy for an infection to spread, as we were many people in the family. She would take us to public baths at least two times every week, either to the one on Slivnitsa Boulevard in our district, or to the central public baths near the city’s central market hall. Wednesdays and Fridays, just before Sabbath, were the bath days. We had to wash our hands, legs, necks and faces every time we entered the house. My sister Sarika [Sara] often bathed us in a washtub in the yard on Wednesdays. My mother had her do this and she took it as a very important obligation. She used to rub us to death, as if we were as filthy as pigs. That raised bursts of laughter.

I remember market days in Sofia very well. On the eve of Sabbath, on Fridays, I would always accompany my mother when she set off to the market. I’m speaking of Georgi Kirkov 3 market that’s still functioning in the [then] Sofia residential district Iuchbunar 4. [Today this market is called ‘zhenskia Pazar,’ meaning ‘woman’s market.’ It is the central open market of Sofia.] For me it was the greatest pleasure in the world. My mother liked shopping for long hours; she also loved bargaining with the sellers. Then I helped her bring the products home. All the sellers were my favorite. The mere abundance of vegetables, oranges, tangerines, and everything made me feel happy.

As I’ve already mentioned I can’t recall anything about my father’s parents. I only know that when they moved from Nis to Sofia they built a huge house for my parents. So, the whole family – the eight kids, my parents, and my father’s parents, lived together in this house. Our house was situated in the poor Jewish district Iuchbunar near Bet Am 5 and the [Great] Synagogue 6. We lived on Odrin Street, while the Jewish school was nearby, at the corner of Osogovo and Bregalnitsa Streets. The yard of our house was also big. We didn’t breed animals but we had a bungalow there that we let out. My eldest brother lived there for some time when he got married, just before the Law for the Protection of the Nation 7 was introduced. Our house was really big, according to the criteria of the time. If we look at it now, it’s just a normal two-storey building.

There were three rooms on the ground floor, and a wooden staircase led to the upper floor where there were two rooms: a bigger and a smaller one. All the eight kids slept in the big one. The smaller one was for my parents. My parents slept in one bed, my brothers in two beds and we, the four sisters, had two mattresses, each of us had a special place one after the other according to our age. Directly on the floor. My place was at one of the ends of the mattresses, since I was born last. And because it was difficult for me to get sleep, I often crept into my parents’ room and I slept underneath their bed. Usually, everyone got up early in the morning, and began to look for me. Finally, they understood I liked sleeping underneath my parents’ bed. I must have been five or six years old then.

I remember that we used to read a lot at home. And we always sang when we went to bed, when we got up, when we felt bad, when we were happy – we always sang. We had arranged our own family choir; there were ten of us after all. We sang in two parts. The second part was of course for men, and we, the women sang the first part. I remember, for example, that my eldest brother was a tenor. My sister Sara was an incredible soprano and could have had a professional career in music, if she had had the opportunity. The others were altos. My parents also took part in our singing. So, without any exaggeration our choir sounded beautiful.

I remember that in our yard a big and picturesque willow grew. During summers, my family used to install a table below the tree and we had our meals there every day. And when we finished with the food, we cleared the table and started singing the most beautiful songs we knew. We sang in Ladino and in Bulgarian. We sang [Bulgarian] folk songs: ‘Kito, girl’ and the now so-called ‘old city songs’ which were in fact modern Bulgarian chansons, called ‘Bufoon’s song.’ We also sang traditional [Ladino] Jewish songs: ‘Adio kerida’ [Goodbye darling], ‘Ande stavne amor?’ [Where are you my love?], ‘Nigna sos de basha djente’ [Girl, you are of an inferior birth], ‘Ken me va tomar a mi?’ [Who is going to marry me?], etc. Of course, my mother knew many songs in Ladino. Mind you, my parents were from Nis, so they knew also many Macedonian songs. [Editors note: Nis is located in Serbia, not in Macedonia.] From Macedonian ones, my favourite was ‘Zapali se Shar Planina’ [The Shar Mountain Started Burning], especially when my mother sang it.

These days I have discovered a hidden, inherited talent in me. I need to hear a song only once to remember it. Every spring, when Pesach was nearing, my mother used to beat out all the carpets, brush and wash everything. She had the furniture taken out, leaving only a table and a chair in the house so that she may reach the ceiling more easily. And she herself painted it. From as young as I can remember, I used to stay around to help her. I carried a bucket of paint, dipped the brushes and then handed them to her. And she would sing all the time. I would remember all her songs. She used to sing as much in Ladino as in Macedonian dialect.

This talent of mine was, however, as much an advantage as it was a disadvantage. I remember Uncle Avram who liked playing tricks on the people around him. He earned his living by making flypapers. Uncle Avram knew that I remembered every song from the first hearing and once decided to play a trick on me. He called me to teach me, say, a very beautiful song. I was quite small and quite enthusiastic about all that. I was eight or nine years old then. He started singing a ribald song and I didn’t know what it was about, ‘Lies down Lola under the quilt, what to say I know not of.’ I came back home and still being at the door I started singing it, content that I had just learned it. My brother, who had never beaten me all my life, slapped me in the face immediately. I got scared and started crying, ‘What’s that for? Why are you beating me?’ And he said, ‘You shouldn’t sing everything you hear from Uncle Avram!’ And he was right. At the same time, my sister Vinka [Venezia] sang an old chanson, it was a popular tune of the time, ‘I live to lo-o-o-ve…’ - very popular it was. And so I started singing it at the top of my voice the following day, ‘I li-i-i-i-ve to lo-o-o-ove.’ It was ridiculous.

The songs I knew in Ivrit I’d learned in Hashomer Hatzair 8. We used to sing a lot there, too. There was a very nice song. It began with, ‘O, ani-i-i itayavti, itaya-avti-i-i…’ We were taught to sing polyphonic music so that it sounded really beautiful. We were divided into two groups. When the first group, consisting of boys, started singing alone the whole first stanza and in the moment when they began the second stanza with a slightly different melody, the second group joined, starting from the beginning and singing simultaneously with the first one. And it always turned out very nice. I remember us singing songs like: ‘Ine ma tov uma naim shevet achim gam yachad’ [literally from Ivrit: ‘how nice and cozy it is, brothers, staying together’], or: ‘Sham baerev…’ [From Ivrit: ‘There, in the evening…’], and so on. It was a wonderful time.

It wasn’t by chance that I mentioned Hashomer Hatzair. When I was as young as seven, I was a member in this Jewish youth organization. I remember very clearly that as early as 1935 Hashomer Hatzair looked after the poor kids, among whom I was, too. We were all from the poor Jewish neighborhood of Iuchbunar. Our fathers were workmen. We studied at the Jewish school where we received free coats and shoes because of our poverty. We were supported economically there, while in Hashomer Hatzair the help was spiritual. And this was more important. They helped us grow up as personalities. This organization gave a meaning to my life. They not only recommended us what to read, I’m speaking of literature with very high artistic values, but also excellently entertained us with games stimulating the sense of unity in our community. Besides, the older boys and girls played the violin for us, so that we could get acquainted with music. For example, the well-known musician Klara Pinkas often played the violin for us.

We studied astronomy as well. And when we turned twelve we started studying Horel’s ‘Sex Question’ [It was then the most popular and highly respected reading for adolescents.] and let me say, not in separated groups of boys and girls, but all together. To put it in other words, they taught us to be friends, and to be united. It often happened that we gathered all our money, about a lev or two per child, and ‘ahot’ [sister in Hebrew] Karola, the girl who was looking after us, she had to make sure we observed the required discipline and she also taught us, distributed them: ‘This is for cinema, this for sweets, and this is for ‘Shkembe Chorba’ [tripe-soup, non-kosher].’ We all loved this Oriental meal.

All my friends then were Jewish girls, whom I was with at the Jewish school and Hashomer Hatzair: Mati Yomtov, Sarika Shamli, Dora Benvenisti and others. Afterwards they left for Israel and since then we have met by chance, well advanced in years, and we have even made out who was who. But back in my childhood years, I was always with them. We had a favorite game called ‘semanei derekh’ [literally from Ivrit: ‘traffic signs’]. We walked in Borisova Garden, the big park in Sofia’s suburbs [today this park is in the city center] separated in groups. The first group had to start before the second one, they walked and from time to time they had to put some signs, for example arrows made out of twigs, to show the direction, or they made some kind of a funny obstacle. Or they improvised a swastika, again made of twigs that meant ‘danger.’ And the ‘danger’ turned out to be a puddle for instance. Or they drew a square and a number in it with chalk. If the number was ten for example the second group had to seek for something hidden at a distance of ten steps from the square. We sought, sought and finally found pink sweets wrapped in a paper.

We often went to the Byalata Voda area, which is on Vitosha [a mountain near Sofia]. We were scouts there. We were separated into two groups: boys and girls. And we arranged fantastic competitions. We ran with our legs in sacks. Liko [Eliu] Seliktar was irreplaceable as an organizer of these games. We were taught how to light a fire in open nature, how to cook and so on. My childhood was absolutely calm. Up to the moment when the Germans invaded Bulgaria and the Law for the Protection of the Nation and the Law for the Protection of the State were introduced.

My father was a brush-maker. He made special shoe brushes and brushes for clothes. In fact, he did the hard work of the brush-making handicraft. When I was a child, I often saw him drilling holes in a board with a drill, where the threads were to be fixed after that. And this board was very thin and delicate and a single false movement could have broken it. But he was a master. I know that the owner of the workshop for brushes on Nis Street, where my father worked, was called Persiodo [Precious]; he was а Jew, too, but I can’t remember his first name now. That’s why he paid my father a substantial amount. His daily wage was 100 levs. Every day at lunchtime, when I was back from school, I carried to my father the meal that my mother had prepared for him. I took home the empty dishes and he would give me his wage to take home to my mother and always gave me a lev. These simple things made every day a holiday for me.

Apart from being a great master, my father was also a very good man. He never slapped any of his children. And he sang beautifully. I adored him. Every day when he came back home I used to wait for him with a basin filled with hot water, because he worked standing all day long and his legs got swollen. I always expected him eagerly and when I saw him approaching with five loaves of rye bread in his hands I rushed and gladly grabbed the bread. After that we used to go to my parents’ room on the second floor. There my father dipped his legs into the hot water and I washed them for him. I was a young child then. This procedure was repeated every single day. I loved him very much, and he loved me, too.

I lost my father very early. He died on 31st December 1939. The reason for his death was that he had a lot of stress then. My sister Ester was to get married. She had match-makers who had found her a boy. In those days, however, it was a big problem for Jewish girls to get married. Every Jewish girl had to have a trousseau, a big trousseau, let me say. But a girl also had to have dowry. And we were poor. My father loved my sister so much that he bought her a ‘Singer’ sewing machine [a very popular one for its time; German sewing machine], he made her a big trousseau and gave her 30,000 levs in dowry, which was a huge amount of money then. And that brought him to ruins. He had taken a loan from ‘Geula’ bank and when the policies started to arrive, he got sick. They threatened to throw out our belongings into the street, take our house and so on. His anxiety created a tumor in his stomach. They told him it was non-malignant, but he had to undergo an operation. And he didn’t want to. So that’s how he passed away. When my father died and the policies continued coming, my sister exchanged her wedding ring at a pawnshop for some money to pay at least the first policy. From then on we lived in complete poverty, especially during the Law for the Protection of the Nation, but somehow we stoically coped with everything.

I remember very well the Sofia Jews’ demonstration in protest to the government’s decision for interning us 9. It was on 24th May 1943 10. At that time I was already 15 years old, but I was not a member of the Union of Young Workers 11, in contrast to my sister Jina, who was. Well, on this day I was just walking down Klementina Square with my sister Jina when we met acquaintances from the Jewish community. They informed us that they were going to organize a manifestation addressed to King Boris III 12 and against his decision for our internment. After that, the whole Jewish community gathered in the synagogue. And our procession started from there to Klementina Square. We reached Father Paisii Street, near Bet Am. And suddenly mounted police appeared in front of us. A severe scrimmage followed while we, the kids, fled away in all directions. I remember that I started running from Father Paisii Street and I stopped as far as Osogovo Street, in the Jewish school. Then I hid with a friend of mine. The police started visiting the Jewish families, from house to house, and they arrested all the Jewish men. Not before long, they interned us.

Our internment was painful. We were each given the right to carry with us only 30 kilograms of luggage. We left for the railway station in order to catch the train to Shumen, where we were to be interned. It was my mother, Vinka, Jina and me. The other two sisters, Ester and Sara, had already been married: in Stara Zagora and in Sofia respectively; while my brothers were sent to forced labor camps 13. When we arrived in Shumen, several hundreds of Jews, we among them, were accommodated at the local school’s gym-hall. And a commune cauldron of food was installed there.

In that confusing situation, we were sitting desperately, my mother, my sisters and I, in the gym-hall’s crowd, when Vinka, who was 20 then already, took the initiative and said, ‘Mum, we won’t live here.’ And we started asking for lodgings. So we came across some Turks who lived near the Tumbul mosque [the main mosque in Shumen, built in 1744, also the largest in the Balkans]. It was just opposite the local Jewish school. Well, these Turks told us they could accommodate us in one of their rooms upstairs. We were six of us in that room: my mother, we, the three sisters, and one of my mum’s cousins with her daughter. We immediately started looking for jobs. We had to dig, wash, clean and all that stuff. We quickly registered ourselves at the Jewish community in the town, where they prepared a list of people like us who wanted to work. So, through the Jewish community we were sent to a ranch of 200 hectares of land. It was situated in the village of Panayot-Volovo. The owner was Ivan Praznikov. Both my sister Jina and I worked there. We dug, harvested and did all kinds of agricultural work there. My elder sister became a seamstress.

After 9th September 1944 14 we finally came back to Sofia. Then I was already 17 years old. We lived in absolute poverty. We found our house overgrown with weeds and grass. The doors and windows were levered out. The furniture had been robbed. A gaping house. We looked at each other and started crying frantically. We were only the three of us. As we were crying, Vinka said, ‘There’s no use in crying. Let’s get things moving.’

We started tearing up the weeds. We cleaned the yard, but the problem was where we were going to sleep for the night. My mother had brothers in Dorbunar [literally from Turkish: ‘Four wells’. ‘Dort’ stands for four, while ‘bunar’ means well, but in every day life people usually don’t pronounce the ‘t’.], a residential district neighboring Iuchbunar. They had come back to Sofia from their internment before we did. And they told us, ‘Until you submit the documents to have the house restored and get help from the municipality, come and stay with us.’ We stayed for a while with our uncles. The house got restored quite quickly in fact; doors and windows were installed. We whitewashed the house, disinfected, cleaned everything and moved in. We gathered our entire luggage in a single corner, because we didn’t have any furniture, we didn’t even have beds. We slept on quilts on the floor.

Just before our internment, my first and second sister, Ester and Sara, who already had their own families, had been working hard. There was a special kind of home-employment for women then. My third and fourth sisters worked for a textile factory. I worked with them. I sewed buttons on shirts, a multitude of shirts every day, so that eventually I didn’t even look at the button’s holes; I knew them by heart. I could finish 60 shirts a day. My third sister got married in Ruse. Vinka’s husband Shlomo was in a forced labor camp during the internment, but he fled to Shumen, where he met my sister and they got married after 9th September 1944.

My brothers succeeded in getting married to the women they loved. In contrast to my sisters, let me say. My elder brother married Olga; his love from the school years. In the beginning, they lived with us. My second brother’s wife’s name is Ani; she lives in Israel. Her father was a grocer; they lived in the Jewish neighborhood, near our place, at the corner of Opalchenska Street and Stamboliiski Boulevard. My younger brother married the girl he loved, also from his childhood. They lived in a bungalow attached to our house in Iuchbunar in Sofia.

Shortly after 9th September 1944 I got married, too. It happened that I had an arranged marriage with an ex-political prisoner; his name was Sason Panizhel. He was a nephew of my sister’s mother-in-law. Once he went to visit his aunt and then he happened to see me there. They arranged a marriage for us and I accepted only because I wanted to get rid of that poverty. My co-existence with him lasted for three years [1945-1947] and it turned out to be real hell.

He took me to Ruse. Yet during the first week, I realized what I was in. But I was still an innocent child brought up with books. I idealized everything. I cried all the time; I just couldn’t stop. Soon my daughter Tinka was born in 1947, and because of her I managed to put up with this nightmare for three years. Our house in Ruse shared the same yard with Dragomir Assenov [a well-known Bulgarian writer of Jewish origin]. Besides, we lived with my husband’s mother, Estel Panizhel, who was close to my mother. His sister was a friend of my sister’s; in Sofia we lived near each other. I lived with him and was in incessant fear. He had acquired some habits in prison that I couldn’t stand.

Sason’s mother was a martyr. And his father wasn’t a good man. I remember him as a very perverted person. And he had passed his perversion to his son. For him, a woman was just a tool for satisfying primary instincts. I was disgusted. Besides, he even reached out his hands to harm me. During that time his cousin, Luna Djain, and I became friends. She often told me, ‘How can you put up with him?’ and I answered, ‘What can I do? Where can I go?’ My parents and my sisters and brothers had all immigrated to Israel by then. And I had nobody in Sofia. Where could I go? Then Luna said to me, ‘You can come and stay with me.’ We lived close to her place then. And one evening when the situation became extremely unbearable, I decided to run away. Just as I was: in a nightgown.

Of course, the situation worsened. At first, he didn’t want to get divorced. He used to go to the kindergarten to pick up our kid. He used it as a lure to make me come back. I was terrified and I let my daughter stay at their place, but I tormented myself with this. I would go to him to ask for my kid, he would let me in, lock the door, beat me, and then chase me away bleeding. Of course, the kid witnessed these scenes and also got disgusted with her father. Luna asked me, ‘Leave him, leave him alone for three days and you’ll see, he can’t handle it with this kid. Why are you going there? Want to get beaten again?’ I was obstinate, though. And everything happened again and again. One day I decided to listen to Luna’s advice. I went there neither the first day, nor the second, and on the third day he came shouting, ‘Take this tag with you, it’s yours!’ That’s what I wanted to hear. And it was over. Afterwards I lived in an even worse condition with my daughter, in complete poverty. We had only my salary as a typist for a living, which was not high at all. At least, I always had some butter to spread on a slice of bread for her.

In 1952 I met my second husband, Georgi Iliev. The same year I found a job with the Regional Council. Georgi worked there, too. He was single and I was in the process of getting divorced. What I liked about him was that he was serious and modest. We got married in Ruse in 1953. Some very big troubles followed on the part of his relatives. The reason was that I was divorced and had a child. His relatives had the mentality of villagers and couldn’t put up with this. Even his father, who had been sent to Germany as a very qualified professional, he worked in the local locomotive plant, said after he came back, ‘It doesn’t matter if she’s divorced; she has a child. But she’s a Jew!’ However, I knew what a wise Jew should do. I stayed silent and waited. I thought this was their viewpoint. I couldn’t press my position on them.

Many years passed before we went to visit them. Until the day my husband’s uncle, who was studying law in France, came back to Bulgaria. He came to visit us. Our son was still a baby then. We sat at the table and started talking, and we talked for long hours, we talked sincerely to each other. He told me a lot of things about France. I don’t know what he said to his sister, my husband’s mother, but after two days she rang the doorbell. I invited her as if we had last met two hours ago. So, step by step they started to invite us to visit them.

Years passed and my mother-in-law died. She didn’t suffer for long; she passed away within a day. It was 1963. The old man remained alone. My father-in-law sold his house and he had to come to stay with us until we had an apartment built. My father-in-law was born in one of the neighboring villages to Ruse, Chervena Voda, which was very riotous after 9th September 1944. In that village the local inhabitants started to make fun of him. They used to tell him, ‘Well, well, Ilia, what happened at the end? A Jewish daughter-in-law, and God knows what else, but a Jewish daughter-in-law is going to look after you, as it turns out.’ And he said, ‘I hadn’t known her. She’s decent. She’s not like us.’ That’s how he spread the fame of me in that village. I looked after this man for 20 years.

My daughter Tinka has two daughters: Rossitsa and Tanya who suddenly decided to leave for Israel after 10th November 1989 15. After my granddaughters immigrated to Israel, my daughter also went there. She has been there for ten years already and lives in Bat Yam. Her second daughter moved to Tel Aviv, while her elder daughter came back to Bulgaria. Rossitsa’s children are called Adam born in 2003 and Maya in 1997. Her husband’s name is Zoar, an Arab Jew, and an intelligent boy.

My son Iliycho [Ilia] Georgiev Iliev was born in 1953 and finished his secondary education at the Ruse music school. We knew he had the talent for music, but we didn’t expect that he would get addicted to music. This way he outlined his own fate. After that, he graduated from the Conservatory [in Sofia], specializing in violin. There he met his wife, Svetla Nikolaeva Toteva, who was also born in Ruse. She’s a cello player. Between 1980 and 1992 they were both members of the [Ruse] Opera orchestra. Then a Brazilian impresario came to the Ruse Opera; I don’t know how he persuaded them, but in 1992 twelve members of the orchestra decided to leave for Brazil to strengthen their orchestra there. Off they went and it’s now twelve years I haven’t seen them. That’s what I feel heavy at heart about. In fact, Iliycho went first and two years after him, his wife and two children, Milena and Nikolay, went to join him. They gave birth to a third child there: Victor.

I have been to Israel seven times. The first time was in 1982 when I went alone. My second visit took place in 1986. From 1989 on, I have traveled to Israel once every three years. I’m impressed that it becomes more and more beautiful there. I like the people, too. My brother-in-law is a Sabra. [Literally cactus fruit in Hebrew, Sabra became the name for the native Jewish inhabitants of Israel. The self perception of Israelis is of the cactus fruit, that is rough and thorny outside and warm and sweet inside.] A wonderful person. Every morning he smiled at me, saying, ‘Miluka kerez kadiyko? Uno Kadiyko? [From Ladino: Milka, would you like a cup of coffee? A coffee?] And he prepared for me a special coffee from selected sorts. His name was Herzel Karmel. He was my sister Jina’s husband. I married before her, even though according to the tradition it was her turn to get married since she was elder than me. He was head of the municipality’s transport department. He was our cousin; his and our fathers were brothers. However, as we know, marriages between Jewish cousins are allowed. As a matter of fact, his surname was Mashiakh. But the people in Israel made fun of this so much that he decided to officially change his surname to Karmel. [‘Mashiach’ means ‘Messiah’ in Hebrew.]

I have experienced every possible misadventure: internment, ghetto, poverty, anti-Semitic regulations, disgraceful yellow star 16, curfew, and so on. So I celebrated 9th September 1944 as liberation. However, I can’t say I accepted 10th November 1989 as liberation, too. Before this date, there were a lot of things I liked. For example, there was more freedom to speak of your ethnical origin; at least, this is my opinion. Less antagonism. More economic safety and social stability. Before, there was a certain category of people, ‘active fighters’ against fascism. They received this date with hostility. Before that, they felt themselves as aristocrats, but this date dispelled their halo. I have never been an ‘active fighter.’ And I didn’t feel any hostility. I can’t say conditions of life changed for me, because I was already a pensioner when the democratic changes in Bulgaria took place.

I retired in 1983. Until then I worked in the Human Resources Department at the Agriculture and Mechanical Engineering Institute in Ruse. I was at a very good self-dependant position and after that I started receiving a nice pension. I had another 15 years length of service before that. So my total length of service runs to 35 years, although I started working as young as a child during the Law for the Protection of the Nation.

The events that took place in Bulgaria after 10th November 1989 didn’t fascinate me. I’m for the tolerance. I never argue with friends in the organization [Milka is speaking of the local Jewish organization in Ruse called ‘Shalom’]: if one supports the Union of Democratic Forces or the Bulgarian Socialist Party, I’m simply not interested in that. Just the other way about. I try to respect other people’s opinions. My sister, who came back to Bulgaria for a while after 10th November 1989, listened to what people were commenting then and told me, ‘Milka, the people here are mad!’ Herzel and I vote with different bulletins. He’s for the conservatives and I’m for the liberals. But should we argue about that at home?’ I think this is the right way of thinking.

Glossary