Mikhail Leger

Mogilyov-Podolskiy

Ukraine

Date of interview: July 2004

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

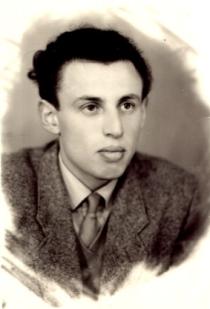

Mikhail Leger and his wife Yelena live in a two-bedroom apartment in a 5-storied apartment house built in 1965. They keep their apartment clean and cozy. Their furniture is not new, but it’s been well-maintained. Mikhail still works in the design office at a plant, though he had reached the retirement age a while ago. Mikhail looks young for his age. He is of average height, thin and quick in his movements. He has thick dark wavy hair with few grey streaks. Mikhail is very vivid and energetic. He is charming and has a sense of humor. Mikhail willingly agreed to tell me about his family and his life. Mikhail and his wife Yelena are friendly and amiable. They make one feel as if you’ve known them for a number of years. Their daughter and her son also live in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. They visit their parents almost every day. Mikhail spends a lot of time with his grandson and knows all about his life and hobbies.

I didn’t know my father’s parents. My father’s family lived in the town of Ozarintsy Vinnitsa region not far from Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My grandfather’s name was Mihel Leger, and my grandmother’s first name was Gita. I don’t know my grandmother’s maiden name, or my grandparents’ date of birth. I guess they both came from Ozarintsy and were born around the 1850s. Ozarintsy was an old Jewish town. There were few synagogues and cheder schools and a Jewish cemetery in the town. There were hardly any newcomers in Ozarintsy, unless somebody brought a spouse from another village or town. There was a shochet in the town. Jews were all religious, and my father’s family was no exception.

I don’t know what my grandfather did for a living, but my grandmother was a housewife like all married women at the time. They had many children. My father Gilel Leger, born in 1902, was the youngest. Of all his numerous brothers and sisters I only knew his sisters Rosa – Reizl was her Jewish name, and Genia. The rest of them moved to America during the Civil War [1] escaping from pogroms [2], and looking for a better life. I have no information about them. All I know is that my father’s brother Shmil died young in the USA and I was named after him. My father corresponded with him before the war, when I was very young. We had a picture of my father’s brothers and sisters that they had sent us from the USA. Some of them moved to Brazil later. During the Soviet period they terminated their correspondence since it was not safe to have or correspond with relatives from abroad [3].

My father and his brothers must have been raised religious and must have finished a cheder school. My father could read and write in Hebrew. He knew prayers and Jewish traditions. My father’s mother tongue was Yiddish. My father must have got some secular education. He worked as an accountant after getting married. My father went to work, when he was young. He never told me about his youth.

My father’s both sisters married Jewish men from Mogilyov-Podolskiy, and moved to live with their husbands. My grandfather and grandmother and my father followed them to Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Rosa’s husband Motl Voloshyn was a clerk in an office. Rosa was a housewife. Her only son Mikhail was born in 1925. His Jewish name was Mihel. My grandfather died in Mogilyov-Podolskiy in 1924. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery of the town according to the Jewish tradition. Mikhail was the first baby born after grandfather died. He was named after my grandfather. Genia husband’s name was Moisey Goldman. I don’t know what he did for the living. Genia was a housewife. They had two children: son Milia, also named after my grandfather, by the first letter of his name, he was born in 1926, and daughter Lidia, born in 1934. After my grandfather died grandmother went to live with Genia. Grandmother died in 1936. She was buried beside grandfather’s grave.

I don’t quite know what Mogilyov-Podolskiy was like at that time, but I don’t think it’s changed a lot since the old times. Vinnitsa region was within the Pale of Settlement [4], and there were many Jews living in its towns and settlements. Mogilyov-Podolskiy is a nice little town buried in verdure. It lies between the Dnestr River on one side and the limestone hills covered with woods – on the other. There were cemeteries on the hills: a Jewish, a Catholic and a town cemetery [Eastern Orthodox]. Bessarabia started on the opposite bank of the river [5]. Jews mostly settled down in the central part of the town. Their houses closely adjusted to one another. There were small backyards where only a little shed or a tiny vegetable garden could fit while in the suburbs residents had orchards, vegetable gardens and fields. They sold food products in the town. There were few markets: the biggest one in the center of the town where there was a shochet working. Jews only bought living poultry to take it to the shochet. Local farmers were well aware of Jewish traditions. On Friday morning they brought lots of poultry and fish to the market knowing that Jewish housewives would want to make chicken broth and gefilte fish for family dinners. Almost all Jewish families had their own suppliers of vegetables, dairy products and eggs. Before the revolution of 1917 [6] most Jews in Mogilyov-Podolskiy were craftsmen or store owners. After the revolution there were plants built in the town and many Jews went to work there. There was a Jewish community in the town. It supported a Jewish hospital, a Jewish children’s home and the needy Jews. After the revolution, when the Soviet regime began its struggle against religion, [7] the community stopped its activities.

There were Jewish pogroms before the revolution and during the Civil War. The power switched from the whites [8], to the reds [9], or various gangs [10]. And they all turned to Jews at the first turn demanding gold or money, or just humiliating, beating, injuring people. Mama told me such pogroms occurred every now and then, and they had to leave their home and look for shelter. Many people gave shelter to Jewish families, though if they had been discovered, those people might suffer a lot, but their kind attitude was stronger than fear. I don’t know any details, but I know that my parents’ families survived the pogroms.

Jews and non-Jews of Mogilyov-Podolskiy got along well and respected each other’s religion and traditions. There were few synagogues, a Christian church [He probably means the Russian-Orthodox Church as both, Catholic and Greek-Orthodox are, of course, Christian Churches too.], a Catholic cathedral and a Greek church in the town. There were cheder schools at the synagogues. There were few shochets in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. After the revolution all synagogues, but 2 were closed. One of these two synagogues, a small one-storied synagogue, was near where we lived. After the Great Patriotic War [11] it was closed for some time, but now it operates again. The second – a choral synagogue, was near the railway station. The Jewish school worked before WW2.

I remember my mother’s family well. My grandmother and grandfather were born in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My grandfather Duvid-Ariye Minkovetskiy was born in 1868. Grandmother Freida, nee Mandel, was born in 1866. I didn’t know any of my grandfather’s relatives, but my grandmother had a sister living in Ataki village on the opposite bank of the river. Before the revolution of 1917 Ataki and Mogilyov-Podolskiy belonged to the Russian Empire. After the revolution Mogilyov-Podolskiy was in the USSR, and Bessarabia was annexed to Romania. Mogilyov-Podolskiy was located on the border. The border between the USSR and Romania was the Dnestr River. There was a restricted entry to the town requiring a special access permit. Frontier guards patrolled the town and the river bank. The bridge that connected the two banks before 1917 was eliminated. There were no contacts between relatives and my grandmother and her sister were separated from each other. However, residents of Mogilyov-Podolskiy and Ataki found out the ways of communication. I remember my grandmother taking me to the bank of the river to bathe. She walked into the river, and her sister was on the opposite bank. My grandmother turned her back to the Romanian bank, so that the frontier guards could not understand, whom she was talking to, began talking loudly about what was new with all members of our family. Her sister talked in the same manner, as if not talking to anybody specifically. Only in 1940, when Romania yielded to the threatening ultimatum of the USSR and gave up Bessarabia, my grandmother and her sister met after a long time.

My mother’s family was miserably poor before the revolution. My grandmother and grandfather rented apartments moving from one place to another. My grandmother was a housewife, and grandfather was the breadwinner for the family. Before the revolution my grandfather dealt in farming. He rented a plot of land from a landlord to farm it. He gave half of his crops to the landlord and had another half at his disposal. After the revolution my grandfather went to work as an acquisition clerk in the supply office that made stocks of fruit and vegetables for Leningrad and Leningrad region. When I was small I liked visiting him at work where I was always given some fruit.

My grandfather was taller than average and thin. He had a small black beard with grey streaks. He wore black suits and a black hat. At home my grandfather wore a yarmulke. My grandmother was short and plump. She wore long black skirts and dark long-sleeved blouses. The only difference between her summer and winter clothes was the fabric, but not the design. My grandmother did not wear a wig, but she always covered her head with a dark kerchief. This was the traditional way the women of her time dressed while my mother and her generation were not so attached to this old tradition.

My grandmother and grandfather had many children, but most of them died in their infancy. Only three of them survived: mama’s older sister Rachil, born in the late 1890s, my mama Paya, born in 1903, and their younger brother Faivish, born in 1907. They spoke Yiddish at home, but also knew Ukrainian and Russian.

My mother’s family was religious. All children were raised religious. Uncle Faivish finished cheder. Mama and her older sister had a visiting teacher. They could read in Hebrew and read and write in Yiddish. They also received a secular education. They finished a 4-year Jewish school and studied in an 8-year Russian school.

Mama’s older sister Rachil married a Jewish man from Mogilyov-Podolskiy. She had a traditional Jewish wedding. Rachil moved to live with her husband. She was a housewife. Her husband Lazar Lerner was an accountant in an office. Their older daughter Bella was born in 1922 and son Abram – in 1932. Mama’s younger brother Faivish studied at the accounting course and then worked as an accountant in an office. He was single and lived with his parents.

Mama was eager to study. She studied at a course for junior medical personnel: attendants and medical nurses. Her dream was to enter a medical college, but this dream was not to come true. She studied and worked as an attendant and then medical nurse in the town hospital. Mama loved her job.

I don’t know how my parents met: whether there was a matchmaker or they met themselves somehow. Anyway, they got married in 1928. My parents had a traditional wedding with a chuppah and a rabbi. I kept my parents’ marriage certificate signed by the rabbi of the synagogue of Mogilyov-Podolskiy for a long time. It moldered in the course of time. Mama and papa rented a little house with one room, a small kitchen and a fore room on a hill in the suburb of Mogilyov-Podolskiy. I was born there in 1935. This house is still there, though many others in this neighborhood have been removed. I can see it from my window. They fetched water from a nearby well in the street. There was a plot of land near the house, about 10 square meters, and the lady allowed mama to make a small vegetable garden there. Mama liked growing dill, parsley and cucumbers, selecting seeds and watching her plants grow.

There was a Russian stove [12] where mama cooked in winter and it also heated the house. In summer mama only stoked the stove to bake bread. She cooked on a small stove on 3 legs. Mama baked bread for a whole week on Friday. It was delicious even when it grew stale. Electricity came to Mogilyov-Podolskiy in 1948. There were kerosene stoves used to light houses before.

My parents spoke Russian to me at home and only switched to Yiddish, when they didn’t want me to understand the subject of their discussion. My parents also spoke Yiddish to grandmother and grandfather.

Mama basically followed kashrut. We never ate pork. Mama bought a living chicken or duck and took it to the shochet to slaughter. She also bought kosher beef and veal from the shochet. Mama had a tray with twigged sides. She soaked meat in water for some time, placed it on this tray, salted the meat and placed the tray into a basin and the blood dipped into the basin. Mama made delicious food. We had gefilte fish on Sabbath and Jewish holidays, and on week days mama made plain food. I remember chicken broth with homemade noodles, cholent, carrot tsimes [13], puddings.

Even during the period of struggle against religion my father remained religious. He didn’t teach me to be religious, but he himself often read his book of prayers. On holidays and on death anniversaries of his parents my father went to the synagogue to recite the Kaddish.

We always celebrated Sabbath at home. Mama made food for Saturday on Friday. She always made cholent that I liked a lot. After finishing baking bread for a week and challot for Sabbath mama put a pot of cholent into the oven where she left it for 24 hours and when she took it out before Saturday dinner it was still hot. In the evening mama lit candles and prayed over them. I remember that mama always covered her face with her hands praying. Saturday was an ordinary working day during the Soviet regime, but mama tried to do no work whenever possible.

We celebrated Jewish holidays. My parents went to the synagogue on these days. They took me with them, when I was small. Before Pesach mama did a general clean up. She whitewashed the house on the outside and cleaned and polished everything inside. There was a Jewish bakery in the town. They baked matzah for Pesach and people made orders for as much matzah as they needed. I don’t remember whether there was bread in the house on Pesach, but surely there was matzah. Matzah was used to make many dishes and also, matzah flour was used to bake strudels and puddings. Mama cooked gefilte fish, chicken broth and puddings. She also made potato pancakes that she also baked in a pot in the Russian stove. She also made borscht for Pesach. Pesia, an old Jewish woman living near the synagogue, made marinated beets for sale. Housewives also bought beet was from her and added boiled potatoes, hard-boiled eggs and matzah to make borscht. It was delicious. I don’t remember whether we had special dishes or Pesach. We were poor. Mama koshered our casual utensils before Pesach putting burning hot stones into pans and casseroles and rinsing them with boiling water. I don’t remember whether my father conducted Seder. I was probably too young to remember.

I remember Yom Kippur well. This was a ceremonious day after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. They blew the shofar for a month at the synagogue and it was heard all over the town. On Rosh Hashanah we had apples cut into pieces and a saucer of homey on the table. We dipped apples in honey eating them to have a sweet year to come. However negative the Soviet authorities were about religion, all Jews came to the synagogue on Yom Kippur that came after Rosh Hashanah. There were people crowding in front of the small synagogue where my parents went. Those, who failed to come inside, were waiting outside for the prayer to be over. The fast lasted 24 hours. Children could have some food during fasting. The next dinner was to take place next day after the prayer was over. Children went to see their parents at the synagogue.

We didn’t make a sukkah on Sukkot since we lived in a Ukrainian neighborhood, but those Jewish families living in the center installed sukkahs in their yards. My grandmother and grandfather also had a sukkah and we visited them. On Simchat Torah my father often took me to the synagogue with him. I carried a scroll of the torah following my father. I had to be very careful since it was a great sin to drop the scroll.

On Chanukkah mama lit one more candle in the chanukkiyah every day. Our relatives and acquaintances visiting us gave me Chanukkah gelt and I always looked forward to this holiday. I spent this money on sugar candy and sunflower seeds.

I also remember Purim. Mama made triangle hamantashen. Mama made many pies to make shelakhmones and send it to relatives and friends.

Mama had to go to work and left me in my grandma’s care or occasionally she took me to my papa’s sister Genia, whose daughter was the same age with me. At 4 I went to the kindergarten near our house. My cousin Lidia Goldman, my father sister Genia Goldman’s daughter, also went to this kindergarten. Though Genia was a housewife, she still sent her daughter to the kindergarten: at that time children were customarily sent to nursery schools to adapt to communication with other children. I was to go to school in 1942.

I remember well the bright and sunny day on 22 June 1941. I remember my parents and mama’s brother Faivish, who came to see us in the morning, standing with tense faces by the black plate of the radio listening to something. Then my mother started crying and told me that the war began. It didn’t mean much to me. All I knew about the war was how we, boys, played the war. I went outside and heard the roar of the planes flying over the Dnestr from Bessarabia. The beginning of the war is associated for me with those planes flying in rows. There were so many planes that they almost covered the sky, and this looked scaring.

My mother’s brother Faivish and Genia’s husband Moisey Goldman went to the army on the first days of the war and so did Rosa’s son Mikhail Voloshyn. Few days later my father was recruited to the army. He went to the gathering point in Vinnitsa. My father’s sister Genia Goldman, her son Milia and daughter Lidia evacuated on the first days of the war. The rest of the family stayed in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Few days later the bombings began. My mother was pregnant. She decided that we should leave Mogilyov-Podolskiy for Vinnitsa from where we could take a train to evacuate. I remember that we rode a wagon to Chernivtsy in about 20 km from Mogilyov-Podolskiy, where we heard that German troops were already in Vinnitsa. We stayed in Chernivtsy where a local Jewish family gave us shelter. We lived in their attic. Few days later my father found us. What happened was – e managed to get to the gathering point, but it was already deserted. He returned home looking for us and somebody told him that we might be in Chernivtsy. My father stayed with us. The village was bombed and during one bombing mama started labor and had a still born baby girl.

Germans came to Chernivtsy in July 1941. I remember their first action against Jews well. Jews were hiding away. Germans captured 10 people, whoever they could find. They took them to the ridge across the river in the village, pushed them off the bridge shooting after them competing in the accuracy of shooting. They were just entertaining themselves. We didn’t see this, but we heard about it – the whole village was talking about it. People knew this was just a beginning. My father walked to Mogilyov-Podolskiy to find out what the situation was like there. He returned and said that we would be safer home. Few Jewish families got together, hired a wagon, loaded their luggage on it and older people and children sat on it to ride to Mogilyov-Podolskiy. This was a hard trip. We had to cross few villages where people abused and tried to rob us. When we arrived home we discovered thee was nothing left in the house: everything was gone while we were away. However, after we returned some neighbors brought back some of our belongings: a table, chairs and some household utilities.

When we returned home, we heard about what happened to mama’s younger brother Faivish. In July 1941 his military unit was retreating through Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Faivish requested a short leave to visit his family. He went to see his parents, but when it was time for him to go back, another air raid began. Faivish was deadly wounded. A military sanitary truck took him away. Some time later grandmother and grandfather received a notification that Faivish had disappeared. I think he died, but nobody took an effort to follow all procedures and notify his military unit. We don’t know where he died or was buried.

Soon Germans established a Jewish ghetto in the center of the town. It was surrounded with a high stone fence with barbed wire on top of it. The gate was guarded by Romanians. After the ghetto was arranged German troops left Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Vinnitsa region became the territory of Transnistria [14], the area of concentration camps and ghettos. It was divided into two zones: Romanian and German. Mogilyov-Podolskiy belonged to the Romanian zone of occupation. All Jews of Mogilyov-Podolskiy were taken to the ghetto. We could stay in our house since it was on the territory of the ghetto. Rosa’s house was aside from the ghetto and Rosa and her husband were forced to leave their house to go to the ghetto. They moved in with us. Grandmother and grandfather also could stay in their house. Their older daughter Rachil, her husband and their younger son also lived with them. Before the war her daughter Bella finished a secondary school and studied at the Engineering Construction College in Vinnitsa. At the beginning of the war Bella evacuated with her college to the Ural. The Ukrainian families whose houses happened to be within the boundaries of the ghetto were forced to move out. Every day groups of Jews from Bessarabia, and even Romania arrived at the ghetto. They were accommodated in Jewish houses. The husband of my grandmother’s sister living in Ataki found us and his family also moved into our house. Some other Jews from Ataki, my grandmother and mother’s acquaintances, told us that Germans killed my grandmother sister’s daughter and her husband, when they came to Ataki. Their only daughter Gita came to the ghetto with other Jews. Mama found Gita, who was 11 years old then and took her to live with us. Later some other of or distant relatives came o live with us. So, in autumn 1941 there were 15 tenants in our house. Our only room was like a fairy tale tower room stuffed with people. My father made a partial to divide it into two parts. In August 1942 another distant relative joined us. My father had distant relatives in the town of Yaryshev near Mogilyov-Podolskiy. There was also a ghetto in Yaryshev. In August 1942 Germans shot about 700 Jews – all inmates of the ghetto in Yaryshev – in a field near Yaryshev and their bodies were falling into a pit. My father’s relatives perished, but their 12-year old daughter Lisa managed to escape. She hid in the corn field nearby and then headed to Mogilyov-Podolskiy. She walked at night and took hiding during the day. In Mogilyov-Podolskiy she found our family and stayed with us. Romanian troops did not arrange mass shooting, but considering the conditions in the ghetto, it was easier to die from hunger and diseases that survive. When I think about it now, I don’t know how we survived. Local villagers brought food products in exchange of clothes and furniture. Since we hardly had anything valuable left, I have no idea how my parents managed to feed us.

Before the ghetto I didn’t know about what Jews were. There was no anti-Semitism before the war. I only discovered that I was a Jew in the ghetto. When they began to shoot Jews there were many talks of this kind and I asked mama: ‘Who invented those Jews?’ mama got confused and told me to ask my grandfather. My grandfather told me the history of Jews and said that Germans could kill us just for the fact that we were Jews’. Later mama often repeated this phrase of mine as a funny joke.

Yiddish was the main language of communication in the ghetto since this was the only language the Bessarabian and Romanian Jews could speak. I learned Yiddish in the ghetto. I couldn’t read and or write, but I spoke fluent Yiddish. Mama often read me Sholem Aleichem’s [15] books in Yiddish in the ghetto. I still have these books. After the war we also often spoke Yiddish at home.

In spring 1942 there was a big flood in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Such floods happened from time to time in the town. When ice begins to melt in the rives it dams it on turning points causing the flooding of nearby areas. Mama told me about the flood in 1932, when thee were even victims among the population. The flood was also terrible in 1942. The whole riverside and a number of houses in the town were flooded. Inmates of those flooded houses had to move into the houses on hills. My grandmother, grandfather, my mother’s older sister Rachil, her husband and son moved into our house as well. They stayed with us for about two weeks. When the water wet back, they moved back into their house. Shortly after this flood a terrible epidemic of enteric typhoid developed in the ghetto. Almost all inmates had lice, there was no soap, all those struck with the disease stayed in the houses where other inmates lived. There were no doctors or medications in the ghetto. There were ill relatives in our house. My mother and father had typhoid during the revolution in 1917 and had immunity against the disease. They were particularly worried about me, Rachil’s daughters and two girls living with us. We were sent to my grandmother and grandfather. Many inmates of the ghetto died. Rachil’s husband Lazar Lerner died and Rachil died soon after him. Our relatives from Ataki died. Mama managed to get some chloride of lime to disinfect the house and we, children, could come back. Mama took Rachil’s son Abram to live with us. Shortly after we left the house my grandfather Duvid-Ariye contracted typhoid and died. The Romanians allowed inmates of the ghetto to bury their dead outside the ghetto. Rachil, her husband, my grandfather and relatives from Ataki were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My father recited Kaddish over their graves. We installed a gravestone after the war. Mama took my grandmother to live with us. My grandmother never recovered after Faivish and grandfather’s death. She was very religious. There was a prayer house in the ghetto and my grandmother attended it regularly. Of course, this was kept a secret from the Romanians.

My mother heard that inmates of the ghetto could be inoculated against typhoid in the town hospital and took me there immediately. The children had to stay in hospital two weeks after inoculations. Many patients fell ill after inoculations, but I was lucky to escape the disease. Only recently we found out that actually these were not inoculations, but experiments on people. The German government paid compensation to those who were ‘inoculated’. But at that time people did not have this information. When the attack of typhus was over, it was followed by an epidemic of enteric fever. It was probably caused by contaminated potable water since the wells were never cleaned through the period of occupation. Mama fell ill with enteric fever and her condition was very hard. Fortunately, she recovered. Then there appeared an epidemic of relapsing fever, and there were many victims to it.

Mama believed I had to study and taught me to read, write and count. Many Jews deported from Romania and Moldavia knew German. Mama hired a school teacher from Bucharest to teach me German. I managed to learn the curriculum of almost 2 years of school in the ghetto.

In autumn 1942 inmates of the ghetto began to be deported to concentration camps: one of them was Pechora camp in Vinnitsa region called the ‘Dead loop’ [16], it was also called the ‘death camp’. There were hardly any survivors in this camp. Prisoners of the camp were forced to work hard and they hardly received any food. They stayed in earth huts and holes that they dug themselves. Those who were too exhausted to go to work were killed. At first Romanian guards made lists of groups of inmates to send them to Pechora, but later they just captured them during raids to move them to Pechora. When raids began adults assigned night watch to warn the others, if another raid began. We lived near a school where Romanians arranged a military storage in a shed in the yard. There were Romanian guards there, and during raids we ran to stay closer to this shed. We thought, if there were Romanians there, maybe the raid would not reach this area. Somehow we really managed to escape the raids.

We had no information about the war. There was no radio or newspapers in the ghetto. When adults got together, all they talked about was that we would be exterminated soon and the ghetto will be liquidated. This was terrible. I was just a child, but I can still remember the feeling of horror and despair that overwhelmed me, when they spoke in this manner. All inmates of the ghetto had this expectation of the end despite their age. Adults and children were sort of living our last days. Hungry and cold during a day, we waited for them to come and capture us at night… Every day and every night could be the last in life.

In March 1943 this expectation of the end was particularly acute. These were horrible days: Germans were retreating, and their columns were passing by our house. Jews feared going outside. They said Germans were going to eliminate the ghetto. On 18 March the Romanians started leaving. The ghetto was not guarded any longer, but nobody dared to leave it. There were German and Romanian troops in the streets that would kill any runaway. Nobody slept at night. Somebody knocked on the door, but we did not open. At dawn on 19 March we heard explosions. Then it became quiet. We stayed inside till we heard the Russian language. Mama went out and called us right away. We could see the rest of the town from the hill our house was on. We saw 3 Soviet tanks coming into the town. They stopped and the tank men showed up. People were coming closer to hug and thank them. They opened their field kitchen and cooked cereals with tinned meat. It had a magic and long-forgotten taste. We felt so happy. We knew that the war not over yet, but we were free. However, it was still dangerous to walk the streets for few days. A German sniper sat in the church in Ataki near Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Later people said that Germans even chained him there so that he could not escape. He kept shooting for 3 days till few Soviet soldiers swam across the Dnestr and killed him. Our relatives went to their homes. Gita returned to Ataki where she found some relatives that had survived. Lisa entered a technical school in Vinnitsa. Rachil’s daughter Bella visited us. Se went to her parents’ grave and then went back to her college in Vinnitsa. Her younger brother Abram went with her. 3 Soviet soldiers were accommodated in our house. The Soviet military restored the bridge across the Dnestr. The peaceful life began, but it did not last long. There were still air raids at nights and people were dying again. There was a railway station not far from our house on one side, and an oil terminal and a bridge on the other side. They were the targets the German bombers intended to hit. Germans dropped fire rockets on parachutes. They lighted the area with ominous red light. Then they dropped bombs. Our old house shook from explosions and the ceiling was falling down. Our family gathered in a bunch in the middle of the room. If we were to be killed, we wanted to be together. Someone told mama that it was best to hide under the table during shooting. Mama made me and grandmother go under the table during shootings. Sitting under the table, I was worried about my parents. The hardest bombing occurred on 7 July 1944. On this day Americans and Brits opened the second front. There was a meeting in the town. Mama went to the meeting and I stayed home with grandmother. It was getting dark, when we heard the familiar roar of German tanks. Then the hell came down. The house was jumping up and shaking from explosions, the plaster came down and the glass broke. When it was over our parents came home. Finally, the bombings were over and the peaceful life began. My father’s sister Genia and her daughter Lidia returned from evacuation. Her son Milia Goldman perished at the front in 1944 and so did her husband Moisey Goldman. Papa sister Rosa’s son Mikhail Voloshyn returned from the front in 1945.

In April 1943 classes at school began. Mama sent me to the 2nd form. Two months later summer vacations began at school. Since I missed the first form at school, I had to take few exams in autumn. I studied in summer and passed my exams successfully. I went to the 3rd form. There were three pupils of my age, born in 1935, in my class. The rest of our classmates were older. There were many Jewish children in my class. We were so used to speaking Yiddish in the ghetto that we communicated in Yiddish at school. Any children started their answer in Yiddish, if they were called to the blackboard. Our teachers asked us to speak Russian. I had no problem with this knowing both languages. There was no anti-Semitism at school. There were Jews among teachers and the majority of school children were Jewish.

There was famine in 1947. I was 12 and remember the feeling of hunger. I couldn’t stop thinking about food. All thoughts about food. In summer we broke into gardens eating unripe apples, apricots and pears. There were cards to receive bread every other day. It was hard to keep a portion of bread till the next day. Mama was taking the bread away, but I found it and cut little pieces from it.

In 1946 my sister Gusta (this name was written in her documents) was born. She was named Gita after my paternal grandmother. My father went to work in a construction office. Mama stayed home through the period of breastfeeding my sister. Later she went to work as a laboratory assistant at the sanitary station. We lived near the laboratory and in the evening all microscopes and reagents were taken to our house for the sake of safety. Mama showed me some specimens in the microscope and I liked watching them. Mama retired in 1983, when she turned 80.

My grandmother lived with us and watched that we observed Jewish traditions very closely. We strictly followed kashrut at home. My grandmother watched very closely that we used correctly dishes for meat and dairy products or tableware, accordingly. Only when she grew very old and could not be so watchful we allowed ourselves some liberties.

When grandmother was with us, we celebrated Sabbath at home. On Friday evening she lit candles. Grandmother had to prepare for the holiday. We didn’t have candle stands and it was difficult to buy candles. We used makeshift means: I removed the inside of a potato, we poured oil inside and placed a little wick in it and we got a candle. When grandmother lit candles and covered her face with her hands when praying she started crying thinking about deceased Faivish, grandfather, Rachil and her husband. Then we sat down to dinner. On Saturday my parents had to go to work, but my grandmother did no work at home. She read the prayer book.

We celebrated Jewish holidays after the war and I took part in celebrations, even though I was a pioneer [17], and a Komsomol member [18]. We were taught to be atheists at school. We knew there was no God and that religion was an opium for people. However, this was one thing, and my family traditions – another thing for me. My family always knew the dates of holidays: Pesach, Yom Kippur, Chanukkah. My grandmother was particularly watchful about observance of traditions. There was always matzah delivered for her before Pesach. I don’t know how strictly kosher this matzah was, but it was there. Some people baked matzah secretly: Soviet authorities had a negative attitude toward religion and religious people. Mama could not afford to buy matzah for all of us, but grandmother had sufficient matzah for Pesach. My grandmother and my parents always fasted on Yom Kippur, only when my grandmother grew too old and could not always look at the calendar, my parents did not tell her about the day of fasting. My grandmother lived a long life and died at the age of 95 in 1961. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery beside my grandfather’s grave according to all Jewish rules.

I studied well at school. I was particularly good at mathematics, physics and chemistry. I was not very good at social sciences, but I had good marks in them as well. We were raised patriots at school. I became a pioneer in the 4th form. I joined Komsomol at the age of 14. Since I was the youngest of my classmates, they joined Komsomol long before I did and I was desperately jealous about them being Komsomol members. I was very serious about getting prepared to admission to Komsomol: I read Lenin’s works [19], and was aware of all political events in the USSR and abroad. I was very proud to show my Komsomol membership card to my parents, when I obtained it.

In 1948 trials against cosmopolites [20] took place. It never occurred to me they were plotted against Jews. I sincerely believed that the Soviet people were denouncing the cosmopolites, who wanted to damage the USSR. My head was so stuffed with the Soviet propaganda that there was no space for doubts in it. I thought that this unfriendly attitude to Jews was justified: there were articles in newspapers about dishonest Jewish directors of stores, shop assistants, profiteers cheating honest people. Of course, my parents, acquaintances and I did not belong to them – I was good! Stalin was my idol and I loved him as much as I loved my own father. We had a framed photo of my father’s brothers and sisters who had moved to USA. I took out the photo and threw it out, and put the portrait of Stalin in this frame. My parents were skeptical about the situation, but they didn’t speak out in my presence. They must have understood that I was to live in this country and they did not want to overburden me with doubts or they were concerned that I might report in them. Who knows…

I remember another important event that occurred in 1948, when Israel was established. Our family was happy about it. We were happy that Jews finally had their own state. Gita from Ataki came to visit us. Before 1940, when Ataki belonged to Romania, Gita was a member of Maccabi, [20]a Jewish Children’s Zionist organization. She was a convinced Zionist and her thoughts never changed after Bessarabia was annexed to the USSR. Her husband also came from Ataki and was a Zionist. Gita talked a lot about Israel and how Jews were fighting for their land and how miraculously brave they were. Gita and her husband intended to move to Israel, but when trials against cosmopolites began, emigration was closed. Gita and her husband did not move to Israel until 1968.

I had my first doubts about the Soviet propaganda during the period of the ‘doctors’ plot’ [22]. I was sincerely indignant about somebody daring to infringe upon Stalin’s life. I was sure newspaper articles were true. It never occurred to me then that this was artificial enforcement of anti-Semitism. I realized this, when once I gave my Ukrainian friend, whom I had known since childhood, a sugar candy. He looked at me with dread: ‘You won’t poison me, will you?’ It was then that I thought that somebody made monsters of Jews, who were ready to poison and kill any person… I started taking a closer look at the events trying to figure out what the situation was about. People thought it was dangerous to deal with Jews – who could tell what they have in mind? Patients refused to visit Jewish doctors, or have a Jewish nurse making an injection saying there was poison in the syringe. It seems ridiculous from today’s standpoint, but then it was scaring. However, I never tied this to Stalin’s name. He remained an idol for me. It never occurred to me that he was to blame for anti-Semitism and that nothing at all could happen in the USSR without his knowledge.

In March 1953 there was another flood in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Our relatives and their children moved to our house on a hill. Again it was like in the ghetto, when a number of people crowded in our room. On 5 March, in the morning, we heard on the radio that Stalin died. Many people cried without trying to hide their tears. I tried to comfort myself thinking that we were all mortal and so was Stalin. He was an old man, but I loved him and believed in him. I had painful fear in my heart. I could not imagine my life without Stalin. When all doctors were rehabilitated later, I felt very sorry that Staling did not live long enough to know that we, Jews, are no poisoning people or rascals.

My illusions were done with, when Khrushchev [23] spoke on the 20th Congress [24] about the crimes of Stalin and his regime. I understood a lot more at the time and believed Khrushchev at once. However, I felt sorry to give up my childhood ideas about Stalin, our leader, the ‘father of people’…

In 1952 I finished school. I already knew that it didn’t matter where I wanted to study. What mattered was where I could be admitted, being a Jew. I grew up quickly and I understood that the routinely anti-Semitism in the USSR spread to the state level. Jews were not admitted to colleges and faced employment problems. Mama wanted me to become a doctor, but I had no hope to be admitted to a medical college. I had to look for a college with lower competition where Jews were admitted, however few of them. Jews had to find a college where they could be admitted rather than starting from choosing a profession. My cousin Mikhail Voloshyn had practical training in Moscow. He found a college with the lowest competition and suggested that I took exams to Moscow Auto mechanic College. I went to Moscow and passed exams, but failed the competition. I returned to Mogilyov-Podolskiy, and went to work as a draftsman at the plant named after Kirov. In 1953 my former schoolmate and I went t Ivanovo town in Russia where we took exams to the Technological College. I failed again. I’m ashamed to say that my examiners discovered that I had a crib and ordered me to leave the classroom. I went to the admission commission to have my documents back. Another Jewish guy from Georgia, who also failed, went there with me. The secretary had the list of our documents in her notebook. When she opened it, we saw the word ‘Jew’ written against our names while there were no notes against other names. The guy from Georgia asked the secretary why this was so and she began to explain that the others were all Russian and there was no need to make such notes. On my way back home I stopped in Moscow and passed exams to the Design Faculty of Moscow technical school of the Ministry of supplies. I stayed in Moscow to study in this school. I lived in the dormitory for 3 years. I studied well knowing that I had to be a high-skilled specialist. I only once heard anti-Semitic expressions from a guy who came to Moscow from a province. The rest of students told me he was a fool and I should ignore him. I finished this technical school in 1956 and had a job assignment [25] to a village in Kaluga region. The local authorities were not very happy to see me. There were hardly any specialists with a diploma. Even director of the enterprise where I was to work only had a certificate of lower secondary education. The local bosses were afraid that I could spoil their careers. One year and a half later I submitted a letter of resignation they approved my resignation, though I had to complete the mandatory term of job assignments of 3 years. I went back home. My parents lived in our prewar house. I went to work at the design office at the machine building plant named after Kirov. This is the biggest plant in the town. I still work there, even though I’ve stepped over the retirement age.

I met my future wife Yelena Kravets at the plant. She was a copy operator at the design office. Yelena was born in Yampol town Vinnitsa region in 1937. Her Jewish name is Leya. Her father Borukh Kravets went to the front during the Great Patriotic War. Yelena’s mother Klara Kravets decided it was dangerous to stay in Yampol and decided to go to Mogilyov-Podolskiy, where her mother and sister lived and took her daughter with her. They only reached Chernivtsy, when Germans already occupied it. In occupation they stayed in Chernivtsy. A Jewish family gave shelter to them. Yelena remembers no details, she was too small then. Chernivtsy was liberated one day before Mogilyov-Podolskiy, 18 March 1943. On 19 March Yelena’s mother perished during an air raid. Yelena was 5 years old, and some people took Yelena to their family. She stayed with them till her grandmother and her grandmother’s sister returned from evacuation. Yelena’s father perished at the front in 1944. Yelena lived with her grandmother in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. After finishing school she went to work as a copy operator at the plant. We got married in 1962. We had a civil ceremony in the registry office, and in the evening mama arranged a dinner for the family. We lived with my parents. My father installed a partial in the room and we lived there for few years. In 1965 the plant constructed an apartment house for its employees and my wife and I received a two-bedroom apartment. My parents also received an apartment in new house few years later. In 1965 our daughter was born. We named her Klara after Yelena’s mother. Yelena entered the extramural school of librarians in Soroki town in Moldavia. After finishing this school Yelena organized a technical library at the plant. She started from just one bookcase of books and in few years their number grew into few thousand books. Yelena became director of this library and worked there till she retired.

I’ve never joined the party. I never wanted to join the party and nobody ever put any pressure upon me. My wife and I celebrated Soviet holidays at home: 1 May, 7 November [26], Victory Day [27]. In the morning all employees went to parades and then we got together at somebody’s place and had parties. We drank and talked. On Jewish holidays my wife and I went to my parents. They still celebrated Jewish holidays. I don’t think there was the so-called Jewry at that time. Te synagogue was closed, and Yiddish was gradually squeezed out of our everyday life. However, we’ve never forgotten that we were Jews. Besides, non-Jews never allowed us to forget it.

I remember how we were concerned during the Six Day War 1967 [28] and the War of the Judgment Day [Yom Kippur War] [29], in October 1973. We felt victorious after the war was over. This was a bright demonstration that Jews were no dweebs unable to defend themselves. When the War of the Judgment Day began, there were rather concerning reports at first. The USSR was supporting Egypt with weapons and military specialists, and our mass media covered only one side of the war. Newspapers wrote that the Israeli army incurred great losses and that the victorious Egyptian army beat its enemies. We worried about Israel and about Gita and her husband, who moved to Israel in 1968. At night we listened to western radio programs that the USSR jammed: the Voice of America [Voice of America and Radio Free Europe were popular radio stations broadcasting Germany in Russian and other Eastern European languages. They were thoroughly jammed in the Soviet Union so that Soviet citizens couldn’t hear the truth about life in capitalist countries and actual state of things in their own country], and others. When I heard that Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula, I felt proud for my people. The Israeli army proved again that it can protect its own country.

When in the 1970s mass emigration to Israel began, I sympathized with those Jews, who decided to move to Israel and I supported them as much as I could. My father’s sisters Rosa and Genia and their families moved there. Rosa and her family settled down in Nathanya, and Genia’s family lived in Holon. My papa’s sisters have passed away, but we correspond with Rosa’s son Mikhail and Genia’s daughter Lidia. Mama’s sister Rachil’s daughter Bella and son Abram also moved there. I couldn’t even consider emigration: my father was deadly ill, and I could not leave him and my mother. My father died in 1972. We buried him in the Jewish cemetery as much according to the rules as was possible at that time. Religious old men came to wash my father. Then he was taken to the ritual hut in the cemetery. A rabbi recited a prayer over him. My father was buried in a coffin, but there was no bottom in this coffin. This was all we could at the time.

My sister Gita lived with parents. After finishing school she moved to Magnitogorsk in Russia [about 2500 km from Moscow], where she entered the Mining College. Our relative Lisa, the girl from Yaryshev, who miraculously survived and lived with us during the occupation, moved to Magnitogorsk after finishing the technical school and getting a job assignment there. She got married and stayed to live in the town. My sister lived with her family during her studies. After finishing the college Gita got a job assignment at the metallurgical plant in Gorky. When my father died I wrote my sister requesting her to come back home. She was reluctant to come back to Mogilyov-Podolskiy, but she did. She didn’t find a job in Mogilyov-Podolskiy and went to work at the metallurgical plant in Ataki. She lived with Mama. Gita was an industrious employee and was soon promoted to deputy director of the plant. Gita married Nikolay Korchmar, a Ukrainian man from Ataki. He and Gita are the same age. He is a driver. They have no children. After the breakup of the Soviet Union Moldavia and Ukraine gained independence. Gita could not live in one country and work in another any longer. She retired. She and her husband live in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. We often see each other. Mama died in 1990. She was buried beside my father’s grave, but it was a secular funeral.

When my daughter was at school, I noticed that her Jewish classmates had Jewish friends and Russian children had Russian friends. This was at the time of Brezhnev’s rule [30], when anti-Semitism became a part of our life. My wife and I wanted our daughter to enter a college in Vinnitsa, but we realized that she did not have a chance to enter a higher educational institution in Ukraine. Klara went to Moscow and successfully passed her exams to the Faculty of Industrial and Civil Construction of the Engineering and Construction College. After finishing it she got a job assignment in the Moscow region. Three years later she came back home and went to work at the construction department. In 1994 Klara married David Roif from Yampol. He was a veterinary. In 1995 their son Ilia, our only grandson, was born. Regretfully, my daughter’s marriage fell apart. She divorced her husband in 1998. David and his parents moved to Israel. Klara and her son live in Mogilyov-Podolskiy.

I‘ve been eager to move to Israel, but it was not to be. At first my wife and I waited till our daughter finished her studies. Our daughter did not want to move to Israel, and we were reluctant to leave her alone here. And now it is probably too late to start a new life.

When general secretary of the Communist party of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev [31] initiated perestroika [32], I felt very positive about it. He gave us hope for a better life. Of course later perestroika took a different direction than we expected. Most people faced problems: the prices went up and their salaries remained the same. However, I cannot say there was nothing good in perestroika. First of all, anti-Semitism receded and we felt it immediately. Perestroika bought freedom of speech and freedom of press. Citizens of the USSR were finally free to communicate with people living abroad, travel there or invite their friends here. Perestroika ended up in the breakup of the USSR. Many people think it was a disaster for us, but I do not agree here. I prefer living in the stand-alone and independent Ukraine to living in the huge empire that the Soviet Union was that the world was afraid of and hated. I think that the breakup of the USSR is a natural process: the history shows us that all empires fall sooner or later anyway. However, I never believed this would happen in my life. Now many people think it’s necessary to restore the Soviet Union, but I think that before we unite again all former SU republics need to learn to live on their own and prove their independence.

Of course, there are occurrences of anti-Semitism, but they mostly emerge from the people of my generation or older. I don’t think it shows up among young people. There is a Jewish life now. There is a lot of Jewish literature and as long as people wish to know things, they have to take an effort to educate themselves. Unfortunately, this came to us too late. The older generation knowing Jewish traditions joined a better world when we were Komsomol members and communists believing that religion was opium for people. Now those, for whom Jewish life was a natural way of life are gone. Young people are not interested, they live a different life and have different values. It’s a pity that the history of the Ukrainian Jewry is coming to an end before our eyes. In the past a rabbi from Zhytomir visited us on Sabbath and Jewish holidays to recite prayers, but he does it no longer due to financial problems. I understand that such activities can only be supported on contribution of Jews from other countries. I understand that this assistance cannot last forever. A community must be self-supporting to exist. We need everybody to become a part of it. If each member gave 10% of his income to the community, as the Torah says, the Jewry would not face this decay. When we receive matzah before Pesach, am ashamed to hear people saying that it is too thick or not crispy enough. If they earn things themselves they would have a better attitude toward things.

I took up Jewish traditions after my father died. Is death struck me. I felt lonely. Then my neighbor lady told me that I had to recite the Kaddish after my father. She wrote the Kaddish to me in Russian letters, and I, being 11 years old, read the Kaddish after my father and then after my mother. I did it at home. The synagogue reopened after perestroika. Every year on my parents’ death anniversaries I read the Kaddish after my parents, as the rules require. I also bring treatments and vodka to the synagogue. I also go to the synagogue once or more times a week. Of course, the services are not quite like I would think they might be. The prayers are read in Russian. I am sure God understands prayers in all languages, but I would rather they were read in Hebrew. Anyway, I am sure that we need a religious and a secular community. I am a member of the board of the Jewish community of the town and know how many problems we have. Most of Jews in Mogilyov-Podolskiy are old and ill people. They need food and medications. The community tries to provide whatever assistance it can. We have a box for contribution where people bring as much money as they can afford. Our compatriots, who visit the town every year on the day of its liberation from the occupants – they make the biggest contributions. Unfortunately, the middle generation of the people in their 40s stay aside. My daughter is very far from the Jewry, but I teach my grandson what it means to be a Jew. When we had a Jewish Sunday school, Ilia attended it willingly. The children were taught prayers and read books about the history of Jewish people. This school was closed due to the lack of funds. Ilia asks me questions and reads a lot. He’ll soon start attending the synagogue with me. I wish my parents came to his bar mitzvah.

Glossary:

[1] Civil War (1918-1920): The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.

[2] Pogroms in Ukraine: In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.

[3] Keep in touch with relatives abroad: The authorities could arrest an individual corresponding with his/her relatives abroad and charge him/her with espionage, send them to concentration camp or even sentence them to death.

[4] Jewish Pale of Settlement: Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.

[5] Bessarabia: Historical area between the Prut and Dnestr rivers, in the southern part of Odessa region. Bessarabia was part of Russia until the Revolution of 1917. In 1918 it declared itself an independent republic, and later it united with Romania. The Treaty of Paris (1920) recognized the union but the Soviet Union never accepted this. In 1940 Romania was forced to cede Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the USSR. The two provinces had almost 4 million inhabitants, mostly Romanians. Although Romania reoccupied part of the territory during World War II the Romanian peace treaty of 1947 confirmed their belonging to the Soviet Union. Today it is part of Moldavia.

[6] Russian Revolution of 1917: Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.

[7] Struggle against religion: The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.

[8] Whites (White Army): Counter-revolutionary armed forces that fought against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War. The White forces were very heterogeneous: They included monarchists and liberals - supporters of the Constituent Assembly and the tsar. Nationalist and anti-Semitic attitude was very common among rank-and-file members of the white movement, and expressed in both their propaganda material and in the organization of pogroms against Jews. White Army slogans were patriotic. The Whites were united by hatred towards the Bolsheviks and the desire to restore a ‘one and inseparable’ Russia. The main forces of the White Army were defeated by the Red Army at the end of 1920.

[9] Reds: Red (Soviet) Army supporting the Soviet authorities.

[10] Gangs: During the Russian Civil War there were all kinds of gangs in the Ukraine. Their members came from all the classes of former Russia, but most of them were peasants. Their leaders used political slogans to dress their criminal acts. These gangs were anti-Soviet and anti-Semitic. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.

[11] Great Patriotic War: On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.

[12] Russian stove: Big stone stove stoked with wood. They were usually built in a corner of the kitchen and served to heat the house and cook food. It had a bench that made a comfortable bed for children and adults in wintertime.

[13] Tsimes: Stew made usually of carrots, parsnips, or plums with potatoes.

[14] Transnistria: Area situated between the Bug and Dniester rivers and the Black Sea. The term is derived from the Romanian name for the Dniester (Nistru) and was coined after the occupation of the area by German and Romanian troops in World War II. After its occupation Transnistria became a place for deported Romanian Jews. Systematic deportations began in September 1941. In the course of the next two months, all surviving Jews of Bessarabia and Bukovina and a small part of the Jewish population of Old Romania were dispatched across the Dniester. This first wave of deportations reached almost 120,000 by mid-November 1941 when it was halted by Ion Antonescu, the Romanian dictator, upon intervention of the Council of Romanian Jewish Communities. Deportations resumed at the beginning of the summer of 1942, affecting close to 5,000 Jews. A third series of deportations from Old Romania took place in July 1942, affecting Jews who had evaded forced labor decrees, as well as their families, communist sympathizers and Bessarabian Jews who had been in Old Romania and Transylvania during the Soviet occupation. The most feared Transnistrian camps were Vapniarka, Ribnita, Berezovka, Tulcin and Iampol. Most of the Jews deported to camps in Transnistria died between 1941-1943 because of horrible living conditions, diseases and lack of food.

[15] Sholem Aleichem (pen name of Shalom Rabinovich (1859-1916): Yiddish author and humorist, a prolific writer of novels, stories, feuilletons, critical reviews, and poem in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian. He also contributed regularly to Yiddish dailies and weeklies. In his writings he described the life of Jews in Russia, creating a gallery of bright characters. His creative work is an alloy of humor and lyricism, accurate psychological and details of everyday life. He founded a literary Yiddish annual called Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek (The Popular Jewish Library), with which he wanted to raise the despised Yiddish literature from its mean status and at the same time to fight authors of trash literature, who dragged Yiddish literature to the lowest popular level. The first volume was a turning point in the history of modern Yiddish literature. Sholem Aleichem died in New York in 1916. His popularity increased beyond the Yiddish-speaking public after his death. Some of his writings have been translated into most European languages and his plays and dramatic versions of his stories have been performed in many countries. The dramatic version of Tevye the Dairyman became an international hit as a musical (Fiddler on the Roof) in the 1960s.

[16] Pechora camp: On 11 November 1941 the civil governor of Transnistria issued the deportation of Jews. A camp for Jewish residents of Tulchin (3005 in total) was established in Pechora village Vinnytsya region in December 1941. This is known as the 'Dead Loop'. In total about 9000 people from various towns in Vinnytsya region were kept in the camp. They were accommodated in the former 2-storied recreation center building. There were up to 50 tenants in one room. No provisions were made for the most basic necessities of the inmates. Inmates hardly got any food and the building had no heating. About 2 500 Jews were taken away by Germans for forced labor. None of them returned, they all died from forced labor beyond their strength, lack of food, hunger and diseases. In March 1944 Soviet troops liberated the camp. There were 1550 survivors left in the camp.

[17] All-Union pioneer organization: a communist organization for teenagers between 10 and 15 years old (cf: boy-/ girlscouts in the US). The organization aimed at educating the young generation in accordance with the communist ideals, preparing pioneers to become members of the Komsomol and later the Communist Party. In the Soviet Union, all teenagers were pioneers.

[18] Komsomol: Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.

[19] Lenin (1870-1924): Pseudonym of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, the Russian Communist leader. A profound student of Marxism, and a revolutionary in the 1890s. He became the leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Party, whom he led to power in the coup d’état of 25th October 1917. Lenin became head of the Soviet state and retained this post until his death.

[20] Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’: The campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’, i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. ‘Cosmopolitans’ writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American ‘imperialism’. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors’ Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin’s death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’.

[21] Maccabi World Union: International Jewish sports organization whose origins go back to the end of the 19th century. A growing number of young Eastern European Jews involved in Zionism felt that one essential prerequisite of the establishment of a national home in Palestine was the improvement of the physical condition and training of ghetto youth. In order to achieve this, gymnastics clubs were founded in many Eastern and Central European countries, which later came to be called Maccabi. The movement soon spread to more countries in Europe and to Palestine. The World Maccabi Union was formed in 1921. In less than two decades its membership was estimated at 200,000 with branches located in most countries of Europe and in Palestine, Australia, South America, South Africa, etc.

[22] Doctors’ Plot: The Doctors’ Plot was an alleged conspiracy of a group of Moscow doctors to murder leading government and party officials. In January 1953, the Soviet press reported that nine doctors, six of whom were Jewish, had been arrested and confessed their guilt. As Stalin died in March 1953, the trial never took place. The official paper of the Party, the Pravda, later announced that the charges against the doctors were false and their confessions obtained by torture. This case was one of the worst anti-Semitic incidents during Stalin’s reign. In his secret speech at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 Khrushchev stated that Stalin wanted to use the Plot to purge the top Soviet leadership.

[23] Khrushchev, Nikita (1894-1971): Soviet communist leader. After Stalin’s death in 1953, he became first secretary of the Central Committee, in effect the head of the Communist Party of the USSR. In 1956, during the 20th Party Congress, Khrushchev took an unprecedented step and denounced Stalin and his methods. He was deposed as premier and party head in October 1964. In 1966 he was dropped from the Party's Central Committee.

[24] Twentieth Party Congress: At the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin’s leadership.

[25] Mandatory job assignment in the USSR: Graduates of higher educational institutions had to complete a mandatory 2-year job assignment issued by the institution from which they graduated. After finishing this assignment young people were allowed to get employment at their discretion in any town or organization.

[26] October Revolution Day: October 25 (according to the old calendar), 1917 went down in history as victory day for the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. This day is the most significant date in the history of the USSR. Today the anniversary is celebrated as ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’ on November 7.

[27] Victory Day in Russia (9th May): National holiday to commemorate the defeat of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II and honor the Soviets who died in the war.

[28] Six-Day-War: The first strikes of the Six-Day-War happened on 5th June 1967 by the Israeli Air Force. The entire war only lasted 132 hours and 30 minutes. The fighting on the Egyptian side only lasted four days, while fighting on the Jordanian side lasted three. Despite the short length of the war, this was one of the most dramatic and devastating wars ever fought between Israel and all of the Arab nations. This war resulted in a depression that lasted for many years after it ended. The Six-Day-War increased tension between the Arab nations and the Western World because of the change in mentalities and political orientations of the Arab nations.

[29] Yom Kippur War: The Arab-Israeli War of 1973, also known as the Yom Kippur War or the Ramadan War, was a war between Israel on one side and Egypt and Syria on the other side. It was the fourth major military confrontation between Israel and the Arab states. The war lasted for three weeks: it started on 6th October 1973 and ended on 22nd October on the Syrian front and on 26th October on the Egyptian front.

[30] Brezhnev, Leonid, Ilyich (1906–1982) Soviet leader. He joined the Communist Party in 1931 and rose steadily in its hierarchy, becoming a secretary of the party’s central committee in 1952. In 1957, as protégé of Khrushchev, he became a member of the presidium (later politburo) of the central committee. He was chairman of the presidium of the Supreme Soviet, or titular head of state. Following Khrushchev’s fall from power in 1964, which Brezhnev helped to engineer, he was named first secretary of the Communist Party. Although sharing power with Kosygin, Brezhnev emerged as the chief figure in Soviet politics. In 1968, in support of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, he enunciated the ‘Brezhnev doctrine,’ asserting that the USSR could intervene in the domestic affairs of any Soviet bloc nation if communist rule was threatened. While maintaining a tight rein in Eastern Europe, he favored closer relations with the Western powers, and he helped bring about a détente with the United States. In 1977 he assumed the presidency of the USSR. Under Gorbachev, Brezhnev’s regime was criticized for its corruption and failed economic policies.

[31] Gorbachev, Mikhail (1931- ): Soviet political leader. Gorbachev joined the Communist Party in 1952 and gradually moved up in the party hierarchy. In 1970 he was elected to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, where he remained until 1990. In 1980 he joined the politburo, and in 1985 he was appointed general secretary of the party. In 1986 he embarked on a comprehensive program of political, economic, and social liberalization under the slogans of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). The government released political prisoners, allowed increased emigration, attacked corruption, and encouraged the critical reexamination of Soviet history. The Congress of People’s Deputies, founded in 1989, voted to end the Communist Party’s control over the government and elected Gorbachev executive president. Gorbachev dissolved the Communist Party and granted the Baltic states independence. Following the establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States in 1991, he resigned as president. Since 1992, Gorbachev has headed international organizations.

[32] Perestroika (Russian for restructuring): Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s, associated with the name of Soviet politician Mikhail Gorbachev. The term designated the attempts to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized, market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratize the Communist Party organization. By 1991, perestroika was declining and was soon eclipsed by the dissolution of the USSR.