Meyer Tulchinskiy

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Oksana Kuntsevskaya

Date of interview: July 2002

I was born in Kiev on 4 February 1924My mother, Tsypa Tulchinskaya [nee Luchanskaya], was born in Tarashcha. Tarashcha was a small distant town. Jews constituted half of its population; the rest were Ukrainians. People lived in peace and friendship and helped each other. They were mostly craftsmen and farmers. There was a synagogue and a Christian church in Tarashcha. Most of the Jewish population perished during the war. The survivors didn't want to return to the ashes of their old homes and scattered all around the world.

My mother's mother was named Mariam Luchanskaya, and her father's name was Isaak Luchanskiy. I don't know how and when my grandfather and grandmother got married. I don't remember my grandfather either. I believe he died in 1935. My mother's parents had their own small business. They bought cattle skin from farmers, made boots out of it and sold them.

My mother said that my grandmother Mariam gave birth to 18 children. Only 9 of them survived. From what my mother told me I know that few of her brothers emigrated to the US during the Civil war of 1917 - 1920 and the period of outburst of pogroms1I have some information about six children. Her oldest son Gitsia (born in 1889) was shell-shocked during WWI and had mental problems. He lived all his life with my grandmother. The next was my mother Tsypa Tulchinskaya (1892), Rosa (1893), Fania (1895), Riva (1900) and Liza (1904). My grandmother was very religious like all other inhabitants of the town. She celebrated all Jewish holidays and followed the kashrut. She went to the synagogue regularly and never left home without putting on her shawl. They weren't a rich family. I remember their small lopsided house, rooted in the soil. There were at least 8 children in a common family in Tarashcha, no matter if Jewish or Ukrainian. People tried to find ways to provide for their families and worked hard to make their living. It's hard to imagine how people lived at that time. They didn't have TV, libraries or movies. The only entertainment was a fair twice a year. The fair was a big thing with fun shows and clowns. The level of culture was very low; people didn't read any books, and the majority of them couldn't even write their own name. They gossiped and made fun of each other. I remember my mother mimicking her neighbors. That way they entertained themselves. It was ... provincial life. You know where a Jew starts? He starts with a funny joke with a double meaning.

There were many young people in Tarashcha in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of them were Komsomol 1 members. They believed that the communist revolution would improve the situation of the Jews, give them more freedom and the possibility to study and live outside the Pale of Settlement 2. I remember a sad incident: A Komsomol activist, a Jew, publicly rejected his father, who was a shochet, because his father slaughtered chickens and was religious. This wasn't quite in line with the revolutionary ideas and communist principles of the son. The Jewish youth spoke Yiddish to one another, but Ukrainian was the language of communication in town. There was one Ukrainian secondary school in Tarashcha, and all Jews finished this school and undoubtedly knew Ukrainian.

My mother said that my grandmother gave birth to 18 children. Only nine of them survived. From what my mother told me I know that a few of her brothers emigrated to the US during the Civil War 3 and the period of pogroms 4. I have some information about six children. My grandmother's oldest son, Gitsia, was born in 1889. He was shell-shocked during World War I and had mental problems. He lived with my grandmother all his life. The next child was my mother, born in 1892, then came Rosa, born in 1893, Fania, born in 1895, Riva, born in 1900, and Liza, born in 1904. My grandparents couldn't afford to give education to all their children. However, all of my mother's sisters and brothers I knew got primary education. In the 1920s the children moved to various towns looking for a job or a place to study. My grandmother stayed in Tarashcha. Her children supported her by sending money and parcels. She didn't receive any pension. She was a housewife and never went to work. My grandmother and her older son, Gitsia, perished in Tarashcha in 1941. Her children were too late to make arrangements for their evacuation. My grandmother and grandfather couldn't afford to give education to all of their children. However, all of my mother's sisters and brothers that I know got primary education. In 1920s the children moved to various towns looking for a job or a place to study. My grandmother stayed in Tarascha. Her children supported her sending her money and parcels. She didn't receive any pension. She was a housewife and she never went to work. My grandmother and her older son Gitsia perished in Tarascha in 1941. Her children were too late to make arrangements for their evacuation.

Rosa was the only one to finish grammar school. After the October Revolution [the Revolution of 1917] 5 she became a party member and an active supporter of revolutionary ideas. She participated in the underground movement in Odessa. Her name, Rosa Luchinskaya, was mentioned in some memoirs of revolutionary figures. I believe she moved to Kiev in 1918. Later her younger sister, Riva, moved to her from Tarashcha. In Kiev Rosa met and married Lavrentiy Kartvelishvili, a Georgian and a Soviet party and government official. He worked in Kiev for many years. During his studies at the Commercial Institute from 1910-1916 he was involved in underground party activities. In 1917 he became a member of the Kiev Committee of the Bolshevik Party, and in 1918, one of the leaders of the underground Bolshevik organization, a member of the all-Ukrainian Provisional Committee. From 1921-1924 he was First Secretary of the Kiev Province Committee of the Ukrainian Bolshevik Party.

It goes without saying that any religious traditions were out of the question for this communist family. Rosa and her husband lived in Kiev for some time. In the 1930s they moved to Moscow. Rosa had a job at the Council of Ministries, but I don't know what kind of position she had there. Her husband was also in the management. In 1937 he was arrested and sentenced [during the so-called Great Terror] 6. It turned out later that he was executed in 1938. Some time before Rosa entered the industrial academy for the training of higher party officials. This saved her life. If it hadn't been for the Academy she would have been arrested, too. She became a party official. During the war she was in Moscow. After the war she continued to have positions as a party official. She died in 1970.

Rosa's son Yury was born in 1920. He finished a Russian secondary school in Moscow and entered the Industrial Institute in Moscow. He lives in Tbilisi now. He graduated as a Doctor of Technical Sciences and became a professor. He was a lecturer at the Polytechnic Institute in Tbilisi. Now he's retired. He married Dodoli, a Georgian woman. She had a difficult life. In the 1930s her father was Deputy Minister of Education in Georgia. He was arrested in 1938. He was suspected of being involved in anti-revolutionary activities. Her mother had died some time before, so Dodoli lost her parents when she was 14 years old. After her father was arrested policemen took her out of the apartment, locked the door and said, 'And you, girl, go away!' Dodoli had to seek shelter at her distant relatives'. They were very concerned about having to give shelter to the daughter of an 'enemy of the people'. Dodoli had a strong will, which helped her to fight all hardships. She finished a secondary school in Tbilisi and entered the Vocal Department at the Conservatory in Tbilisi. Later she became a teacher at this Conservatory. She fiercely hated the Soviet regime. When her father was rehabilitated 8 posthumously in the 1950s, she made every effort to have all their property, which had been confiscated in 1938, returned.

My mother's sister Fania moved to Tbilisi from Tarashcha 5-6 years after the October Revolution and stayed there. I don't know what brought her to Tbilisi. She married a Polish man named Kalnitskiy. He was an irrigation engineer. Fania was arrested in 1937 and sentenced to five years of imprisonment for her contacts with an 'enemy of the people', Rosa's husband, who often visited his relatives in Tbilisi. Besides she was accused of not returning books by forbidden Soviet writers to the library. She had the right to write to her relatives and informed them what she was charged of. Fania was in a camp in Perm region until 1939. Rosa, who was studying at the Industrial Academy went to the authorities and said, 'Why did you arrest her? In that case you should arrest me for my contacts with an 'enemy of the people', too'. However strange it may sound, they released and rehabilitated Fania and even suggested that she entered the Communist Party, but Fania refused. Some time later she was appointed director of a Russian school in Tbilisi. After I returned to Tbilisi from the front, Fania and I visited her former students in Tbilisi, and I witnessed the respect they treated her with. She died in 1966. She had two children. Her son, Alexei, became a Candidate of Technical Sciences. He settled down in Moscow when he was an adult. Her daughter, Medeya, married a Georgian man and divorced him later. She lives in Tbilisi now.

My mother's sister Riva finished an elementary school in Tarashcha and helped her parents with their leather business. Rosa was a big influence on Riva and her other sisters. Riva got involved in revolutionary activities. Although she didn't like to study she finished a Russian secondary school in Kiev after she moved there. She remained undereducated though. She was a typical Komsomol activist of the 1920s: indefatigable, energetic and uneducated. My mother used to say about her that she had a strong personality. Riva tried to study at the textile institute but gave it up. She wasn't an industrious student. She changed jobs every year. Before evacuation she worked at the Franko Theater in Kiev. Riva was an assistant trade union leader. A well-known actor called Shumskiy was the trade union unit leader. This was the period of 'red directors'. Riva fit into this role well: she was a party member and was responsible and energetic.

Riva lived in a small room near the Franko Theater and was very poor. She lived in Kiev for over 20 years. I remember that she didn't have any clothes to have her picture for the passport taken, so she borrowed a blouse from the dressing room in the theater. Riva was a straightforward and honest woman. She lived with a Ukrainian man; they didn't register their marriage. They didn't have any children. During the war she was in evacuation in Tbilisi. She kept changing jobs there, too. During the war she worked as a tutor at a labor penitentiary institution near Tbilisi. After the war she was a receptionist in the governmental room of the railway station in Tbilisi. This was a privileged position: only deputies and high officials were allowed into this room. Riva visited Kiev several times. During one of her visits I went to the theater with her, and I was struck by the praises Riva got from the leading actors. They admired her trade union leadership activities. Riva was a very pure and transparent person. She died in Tbilisi in 1974.

My mother's sister Liza didn't have any education or profession. She followed her sisters to Kiev, got married and became a housewife. Her husband was a carpenter. He had a Jewish education. He finished cheder and could read the Torah. His name was Meyer Rabinovich. Thank God the disasters of 1937 didn't affect them. Liza and her husband often visited my parents, and I entertained my cousins. Liza had three daughters. Meyer liked to discuss political and general issues with my father. They were the only religious family among our relatives, they observed traditions and celebrated holidays. I believe, they celebrated Pesach and Yom Kippur. They had quiet celebrations, and I heard about it incidentally, so I don't have any details.

When the war began their family evacuated separately from ours. Liza's husband was working at an enterprise that evacuated their employees and families. They crossed Siberia by train. At one station they had a discussion with the director of an enterprise. When he heard that Meyer was a carpenter he offered him a job. They stayed there. Meyer made boxes for ammunition, and Zina, his older daughter, worked at the same military plant. She received 600 grams of white bread. She was 14 years old at the time. Their youngest daughter died on the way to evacuation. After the war Liza and her family returned to Kiev. They didn't have any problems with getting an apartment. Meyer got his job back, the same as he had before the war, and received an apartment. Aunt Liza never went to work. She died in 1978. Liza's daughters Zina and Sima live in Kiev. They are married and have children and grandchildren.

My mother was the oldest of the girls in the family. (Photo 1). I don't know what kind of education she had. She could write in Hebrew and Yiddish, which was rare for a woman. She liked reading and read classic literature in Yiddish and Russian. She could also write well in Russian. She had many friends and corresponded with them all her life. She was helping her parents with the shoemaking business before she got married. My mother told me little about the years of her youth. I don't know when and how she met my father. I only know that my parents had their wedding in Tarashcha during the Civil War. They were hiding from gangs 8 in Tarashcha and I don't think they had a real wedding party. The situation wasn't good for celebrations. There were Denikin 9, Polish and Petliura 10 units in town. The power in town changed from one to the other, but they all persecuted Jews, of course.

My father, Lev Tulchinskiy, was born in Zhivotov, near Tarashcha, in 1891. I don't know anything about his family. My parents told me very little about themselves. I only picked up bits and pieces of conversations. It was my understanding that my father didn't have pleasant memories about his childhood. I remember one little anecdote that my father told me. He recalled how his parents were hiding freshly made bread from the children. There were many children in the family, and they ate too much freshly baked bread whenever they could get it.

My father studied in cheder and later entered the yeshivah in Vilnius to study to become a rabbi. He was probably religious when he was young. He probably observed Jewish traditions, which was common in all Jewish families back then. He never finished his studies because he got disappointed with religion. It was the time of chaos. My father took to another extreme: he participated in the Revolution of 1917 and the Civil War. I believe he was wounded in 1919 and had to stay in hospital. This created some distance between him and his relatives. His family ended up in Winnipeg, Canada, in their effort to escape from pogroms. They settled down there and had a good life. During the famine in Ukraine 11 my father's relatives sent him parcels. They changed their last name from Tulchinskiy to Tulman to make it sound more English. We haven't been in touch with them for quite a long while.

After he was wounded my father still led an active life, but he didn't become a member of the Bolshevik Party. He wasn't really happy about the regime in his country, even though he had been fighting for it. He got disappointed with the idea of communism. My father called people in power 'these smooth-talkers'.

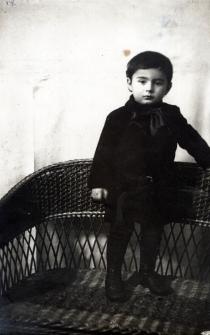

My father and mother moved to Kiev from Tarashcha in the 1920s. They rented an apartment in the center of the city. I was born there in 1924. (Photo 2). My father worked as an accounting clerk at the Kievfuel Trust. This trust supplied coal, wood, kerosene, gasoline and lubricants to enterprises in Kiev. My father was very fond of self-education. He showed an interest in political economy and politics. He wasn't interested in fiction. He liked to read newspapers and sent me to buy Pravda and Izvestiya [communist newspapers.] He enjoyed discussing political issues with his daughters-in- law, Rosa and Riva. Meyer joined them sometimes. Political education was mandatory at that time, and all employees had to take exams at their offices. I remember Riva, my father and somebody else getting prepared for these exams.

Basically my parents were in favor of the Soviet power. If you ask me whether there was anything positive about the Soviet power my answer would be, 'Yes'. This refers to education first of all. When I went to school we had several textbooks in mathematics written by different authors. After some period of probation the education authorities decided to switch to the pre-revolutionary textbook written by Professor Kisilyov from Voronezh. The Soviet authorities favored him and awarded him the order of the Red Flag. I remember his words: 'The country where almost all people study needs good textbooks!' He didn't exaggerate. Even the poorest could get free education. Young people studied in all kinds of educational institutions including military, engineering, accounting, law and philosophy colleges.

My parents spoke Yiddish with each-other. Sometimes they communicated in Russian, when they also wanted me to get involved in the conversation, or if someone else was in the house and didn't speak Yiddish. I'm surprised that my parents didn't even try to teach me Yiddish. Regretfully, my parents didn't celebrate any Jewish or religious holidays or observe any traditions. I rarely visited my mother's mother in Tarashcha. My relatives spoke Ukrainian to me, and I don't remember celebration of any religious holidays. My relatives got together on Soviet holidays at our place. I was the only child in the family. My mother had babies several times, but they all died.

I studied at a Russian secondary school in Kiev. It was located near the Ukrainian Drama Theater and school children participated in the performances. We often went to the theater. I remember the terrible famine of 1933 well, although the situation in Kiev wasn't as tense as elsewhere. I remember long lines of people waiting to get bread. There were supervisors to watch the order. After the government moved to Kiev from Kharkov in 1934 life improved a lot. Kiev, as the capital of Ukraine, had better supplies of food products.

We lived in the main street of Kiev, Kreschatik. We had a huge room and seven other families were our neighbors in the same apartment. My parents separated my part of the room with a screen, which they bought from the sales. It was a heavy mahogany screen, upholstered in a beautiful manner. My parents and I had iron beds. We had a sofa with a high back, a carved cupboard, a floor mirror and a table in this room. We also had a radio.

My mother was a very difficult woman, a family despot. She always interfered with my life. But I'm grateful that she taught me how to read. She died with a book in her hands. She preferred fiction. My mother didn't work because she was constantly ill. Besides, there weren't enough jobs for everybody at that time. She was a very good cook. Her stuffed fish and jellied meat were delicious.

I remember 1937 when a large number of people were arrested [during the Great Terror]. I was studying at the governmental school [school for the children of high officials] located in the vicinity of Lipki, an elite neighborhood of Kiev. There were children of high Soviet officials and military in my class. The children's parents were arrested as 'enemies of the people' and often physically maltreated, executed or sent to camps with extremely hard living conditions,0 and the children were sent to children's homes or shelters. They were arresting higher officials and common people. There were two Polish girls in my class whose parents were clerks. They were arrested, and the girls were sent to a children's home. I never saw them again.

My father was an accounting clerk, and this campaign didn't affect him. His nationality was of no significance at that stage. Aunt Fania, who lived in Tbilisi, had her nationality written as Russian when she obtained her passport. She mentioned that she wasn't Russian, but she was told that all citizens were Russian. Many people liked the fact that all were equal and that there were no first or second-class people any more. However, this didn't last long. In 1939 the Department of Judaism at the Institute of Linguistics in Kiev was closed. It moved to Birobidzhan 12. The authorities closed Jewish schools pretending they were responding to the request of the children's parents.

I heard about the war at 12 o'clock on 22nd June 1941. We had a radio. At that time that was even more prestigious than having a car nowadays. We had the reputation of being rich because we had a radio. We turned the radio on and opened the door so our neighbors could hear the announcement about the war.

After a week the military office sent us to excavate trenches near Goloseyevskiy forest in the vicinity of Kiev. We spent a week there. After we returned to Kiev we were sent to Donets. We were too young to be recruited to the army, but we were to come of age, and it was the right step of the government to send us to a remote area as a reserve for the Red Army. My parents evacuated. My mother's sister Riva helped them. She worked at a bank and they were the first to evacuate. Riva was allowed to take my parents into evacuation. They came to Donets to pick me up. The Germans were approaching Donets and the military office didn't keep young people any longer.

It took us a long while to get to Middle Asia. We stayed at a collective farm 13 in Uzbekistan. We worked in the cotton fields and lived in a kibitka [clay hut] with a very small window offering a view of the kishlak [an Uzbek village]. We spent about half a year in Uzbekistan. People were dying like flies. They were dying from eating mulberries and fruit after starvation and drinking water from the river. They died from dysentery and bloody flux. A lot of children were dying. There was even a separate cemetery for children.

Riva, who was living in Tbilisi, came to our rescue again. There was a labor camp for children somewhere in the Caucasus and a factory in it, and Riva was employed as a tutor there. She managed to send us the necessary forms to come and work at this camp for youngsters. We traveled to the Caucasus from Middle Asia across the Caspian Sea. My father had a weak heart after working in the cotton fields. He died on the way at Ursakievskoye station in Middle Asia. He was buried quietly there. We reached Tbilisi, and I entered the Communications College where I studied for several months. I lived in the hostel, and my mother rented a room. In 1942 the Germans came close to Zakavkazye and total mobilization was announced in Tbilisi. 300,000 recruits went to the front, and I was among them. Every third one of them perished.

My mother got a job as a medical nurse at the navy hospital in Tbilisi. The Georgians treated my mother very well. As soon as I went to the front she was registered at the military office as a member of the family of a front line soldier, and she moved to an apartment where she lived until the end of the war. This hospital gave treatment to wounded military of the southern front. I was at the 3rd Ukrainian front. My mother was always looking for me among the wounded soldiers who were being brought to the hospital. I wrote to her but now I think I could have written more letters to her.

I was a private at the infantry, at the Zakavkazie, North Caucasian front, from where we moved to the South Ukrainian front. I was wounded by a stray bullet on a battlefield in Hungary in April 1945. I remember this incident as if it happened yesterday. I was sent to a field hospital and then to Odessa. Later I moved to Sochi where all recreation centers were turned into hospitals. After Sochi I was sent to Yenakiyevo in Central Russia to complete my course of treatment. (Photo 3).

My mother found out that I was in Yenakiyevo and wanted to come and visit me, but she wasn't allowed to leave her work. Then she got a chance by accident. Two majors, who had lost their legs, needed an escort to return to Russia. My hospital was near where they lived in Russia. It was a difficult mission with lots of arrangements to be made on the way, and nobody wanted to take it. The director of the hospital suggested that my mother went. She agreed, but her condition was to have a statement reading, 'Visiting Yenakiyevo to meet her wounded son', written in her route document. The director of the hospital didn't agree with it but she insisted that he did what she was asking for. She escorted both majors home - they were miserable people. She came to Yenakiyevo, and I was released from hospital.

We went to Tbilisi, but I didn't feel at home there. We decided to go to Kiev. We weren't awaited by anyone. Our place had been destroyed, and we didn't have a place to live. It was a good thing that I kept my passport during my mobilization to the army. It was a hectic moment at the military office. There were many recruits, and they all submitted their passports to have them replaced with military identity cards. The clerk sitting at his table had heaps of passports scattered on the floor around him. He probably thought that these soldiers wouldn't need their passports later on. I put my passport into my pocket when he wasn't looking and thus managed to keep it. It wasn't a good idea to have one's passport during the war. If the Germans had ever captured me and seen that I was a Jew they would have shot me immediately. I was hoping to be able to throw it away if necessary. After we arrived in Kiev I went to the social support office to be registered there. The chairman asked me whether I could prove that I had lived in Kiev, and I showed him my passport. He saw my address and gave me a 200-ruble allowance to rent a room.

After the war I had an aversion to everything that I had seen or lived through during the war. I'm reluctant to answer questions related to the war. I had finished 9 years at school before the war. After the war I told my mother that I wanted to get higher secondary education. I need to give credit to my mother because she supported this idea of mine in spite of all misery we were living in. My mother respected educated people. She said that an uneducated person could hurt other people's feelings, however unintentionally, and she avoided such people. I started to study at an evening secondary school in 1945 and finished it with a silver medal in 1946.

I submitted my documents to the Kiev Polytechnic Institute. There were many applicants for the Radio-Engineering Faculty, but I was admitted because I was a medal winner and a war invalid. I lived in the hostel, and my mother rented rooms. Later I received a small room in Podol 14. After graduating I worked at the Communications Department of the Hydro-Meteorological Center. Later I had several jobs. I didn't have any acquaintances and couldn't get a really good job. I didn't mind because I liked my work. Another reason for my not being able to get a better job was that this was all during the period of the campaign against cosmopolitans 15.

As for the Doctors' Plot 16 I would like to say that there has always been anti-Semitism in USSR. I remember that parents at that time didn't allow their schoolchildren to accept medication from a school doctor if they found out that the doctor was a Jew. I think, the basis of anti- Semitism is people's ignorance and stupidity. Stalin's death in 1953 put an end to this period. Erenburg 17 has an interesting description of this period. The Evening Kiev newspaper published anti-Semitic articles and notes. There were always Jewish names mentioned if something indecent happened. One might have imagined that all existing jerks at that time were Jews.

I worked as head of the communications office at the Zhuliany airport in Kiev at the time. We had meetings where people were pointing at the 'enemies', accusing them of embezzlement, espionage in favor of other countries, negligence, carelessness and dishonest attitudes. We were bound to get involved in the persecution of innocent people, as well as in their dismissal from work. Of course, I sympathized with them and understood that they were innocent, but there was nothing I could do. It wasn't wise to fight against the Soviet regime. The situation was very bad, of course. However, I didn't face any anti-Semitism myself. People always treated me with respect. I was head of the medical equipment design office for a few years before I retired in 1989.

My mother worked as a janitor and later, after the war, as a telegram deliverer. She received tips from the people who received good news about their loved ones from the front. Mistakes were made, and families were notified of their relatives' death when in reality they were captives or wounded in hospitals and just weren't able to let their families know that they were alive. Therefore, after the war, many people got news from their loved ones. Once my mother delivered a telegram to an old couple. They had received notification before that their son had perished at the front. The one that my mother brought them was from their son saying that he was fine and heading for Kiev.

My mother had a poor heart and she often felt very ill. Perhaps, it was for this reason that she liked to be visited by doctors. She was very concerned about me not getting married. She didn't care about the nationality of my future wife. One of my mother's sisters married a Georgian, another one married a Polish man. My mother married a Jew and so did her sister, Liza. Riva's lover was a Ukrainian man. So, if we hadn't been continuously reminded that we were Jews, we would have probably forgotten about it once and forever. My mother died in 1963.

I met my future wife, Alexandra Aizman, a Jew, in 1967. She came from a Jewish family with many children. Her father, Naum Aizman, was born in the town of Gusyatin, on the western border of Ukraine, in 1899, I think. Her father had an elementary education. He probably studied at cheder. Before the war my wife's father was chairman of a shop in Gusyatin. My wife's mother, Sarah, was born in 1915. She finished a Ukrainian elementary school. She didn't have any profession. She married Naum Aizman in 1935 and became a housewife. They had 3 children. My wife's parents didn't celebrate any Jewish holidays or observe any traditions. After the beginning of the war their family evacuated to Middle Asia. My in-laws' children died from dysentery and pneumonia. The food and water were very poor and the conditions of living very hard in the place where they lived. Many children died of infections and lack of food.

After the war my father-in-law went to Shargorod, located close to his hometown. There's a synagogue, a church and a cathedral in Shargorod. This town had Jewish, Polish and Ukrainian inhabitants and people lived in peace with each other. They spoke Yiddish and Ukrainian in Shargorod. During the war there was a big ghetto there. The majority of Jews were exterminated, and the ones that survived left for other places after the war. There are hardly any Jews left in Shargorod today.

They had three children born after the war: Dmitriy, in 1945, my wife Alexandra in 1946, and Dora in 1947. My father-in-law became a soda water and lemonade expert in Shargorod after the war. He created his own recipes and made syrups. The local authorities allowed him to open a store in Shargorod. Although it was a state-owned store he had his own customers and could provide well for his family. His products were in big demand and he earned well.

My wife's older brother, Dmitriy Aizman, finished the Road Transport College and was a driving teacher at a technical school in Shargorod. Dmitriy married a local girl named Anna. They had a big wedding party, but I don't remember whether theytraditional Jewish wedding. He was a member of the Communist Party. They had two children. They led a quiet life, didn't have any hobbies, didn't celebrate any Jewish holidays or observe traditions. In the 1980s they went through hard times when the Soviet regime was collapsing. Dmitriy found a profitable business. He took a course and learned how to make smoked fish. He opened a smoking shed and became a fish supplier. He died when he was 54. His older son, Alexandr, his wife and her parents emigrated to Germany in 1996. Anna also moved there after Dmitriy died. Anna's younger son, Igor, became very religious. He grew a beard.... Nothing of this kind had ever happened in our family before. In 1999 he was in a camp in Israel. He received a student's visa to the USA and went there to study to become a rabbi. I don't know whether he finished his studies or not, but he stayed in the USA. His religiosity came to him somehow even though his mother Anna had never been serious about religious issues.

My wife's younger sister, Dora, was born deaf and dumb. She studied at the boarding school for deaf and dumb children and became a tailor. She worked at a tailor's in Shargorod. Dora married a deaf and dumb man from a neighboring town in 1970. Her husband was a good carpenter, cabinetmaker and welder. He worked at a construction company for some time. They didn't observe any traditions or celebrate holidays in Dora's family. I think the reason was that none of our families ever had any celebrations. Dora's eyesight got so bad that she became almost blind. In the 1990s perestroika began, and her husband lost his job. Dora couldn't earn anything, they had five children and were literally starving. Their family moved to Israel in 1996. They still live there now, but we aren't in touch with them.

My wife was born in 1946. She was 22 years younger than me. She finished a Ukrainian secondary school and a pharmaceutics school in Shargorod and came to Kiev to enter Medical College. She rented an apartment from my Aunt Liza. My cousin, Zina, decided to introduce us to each other. We had a civil wedding ceremony in 1966. Her father came to Kiev at least once a month. Her mother didn't come because she was rather sickly. She didn't even attend the wedding. We often went to Shargorod. My father-in-law died in 1968 and my mother-in-law in 1979. My wife's parents were sociable and had many friends in Shargorod. (Photo 4). They spoke Yiddish in my wife's family. However, Alexandra and all the other members of her family spoke Russian or Ukrainian to me.

After our wedding we lived in the communal apartment 18 in Podol. Some time later we purchased an apartment in Obolon. My wife was a nurse in a hospital in Kiev. She was a highly qualified medical nurse. She did her job very well, and sometimes she even corrected doctors if they were wrong. She had many acquaintances she consulted on medical issues. My wife was so highly valued at work that she was offered to be admitted to the Medical Institute without exams. Alexandra was planning to study at the Institute, but she died from cancer in 1988. We lived a short but happy life together. I feel so sorry that she spent so much time doing additional work to earn a little more money: she gave people injections, looked after sick people, and so on. Alexandra was a very easy-going person, and we had great family and friend gatherings on Soviet holidays. She shared my fondness of classical music, and we often went to the Philharmonic and theaters. We didn't celebrate any Jewish religious holidays - it simply wasn't a tradition in our family.

Our daughter, Tsessana, was born in 1969. (Photo 5). She finished a Ukrainian secondary school in Kiev and entered the Pharmacological Institute in Leningrad in 1986. She studied there for two years. She married Oleg Impriss, a Jewish man, in 1988. He worked as a locksmith at a plant in Kiev. They emigrated to Germany in 1989. My granddaughter, Alexandra, was born there. My daughter tells me to join them, but I don't want to go. I don't even like the thought of Germany or the language. It probably has to do with my associations from the war times. Besides, all these long process of getting the required documents is a problem for me. I haven't even visited them, although I love my daughter and granddaughter, and I'm very attached to my son-in-law.

It's difficult for me to say what I think about emigration in general. It all depends on how adjustable an individual is. Some cats and dogs could return home covering the distance of over 1,000 kilometers. Scientists call it the 'sense for home'. If animals have this feeling for home, some people must also have it. I think it's alright to go to work at some place and return home afterwards. When it comes to looking for personal happiness it's a different matter. Basically, Israel is supposed to be our historical Motherland. But the situation isn't simple there. I like to listen to the Israeli radio station, read newspapers and books about this country. I would like to visit Israel, but again, it's a problem to stand in lines to obtain documents. Besides, it's expensive for a pensioner to go on this trip. Also, I'm concerned about the latest events in this area: all this shooting and terrorism.

I live alone. I read a lot and meet up with my friends, relatives and neighbors. I feel okay. It's a pity I can't see my daughter and granddaughter more often. I know that there are many Jewish organizations in Kiev. I don't go there. I'm not interested, and I don't need to go there.

Glossary

1 Komsomol

Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.2 Jewish Pale of Settlement

Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.3 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti- communist groups - Russian army units from World War I, led by anti- Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.4 Pogroms in Ukraine

In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.5 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during WWI, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.6 Great Terror (1934-1938)

During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor. Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public 'show trials'. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.7 Rehabilitation

In the Soviet Union, many people who had been arrested, disappeared or killed during the Stalinist era were rehabilitated after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, where Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin's leadership. It was only after the official rehabilitation that people learnt for the first time what had happened to their relatives as information on arrested people had not been disclosed before.8 Gangs

During the Russian Civil War there were all kinds of gangs in the Ukraine. Their members came from all the classes of former Russia, but most of them were peasants. Their leaders used political slogans to dress their criminal acts. These gangs were anti-Soviet and anti-Semitic. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.9 Denikin, Anton Ivanovich (1872-1947)

White Army general. During the Russian Civil War he fought against the Red Army in the South of Ukraine.10 Petliura, Simon (1879-1926)

Ukrainian politician, member of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Working Party, one of the leaders of Centralnaya Rada (Central Council), the national government of Ukraine (1917-1918). Military units under his command killed Jews during the Civil War in Ukraine. In the Soviet-Polish war he was on the side of Poland; in 1920 he emigrated. He was killed in Paris by the Jewish nationalist Schwarzbard in revenge for the pogroms against Jews in Ukraine.11 Famine in Ukraine

In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.12 Birobidzhan

Formed in 1928 to give Soviet Jews a home territory and to increase settlement along the vulnerable borders of the Soviet Far East, the area was raised to the status of an autonomous region in 1934. Influenced by an effective propaganda campaign, and starvation in the east, 41,000 Soviet Jews relocated to the area between the late 1920s and early 1930s. But, by 1938 28,000 of them had fled the regions harsh conditions, There were Jewish schools and synagogues up until the 1940s, when there was a resurgence of religious repression after World War II. The Soviet government wanted the forced deportation of all Jews to Birobidjan to be completed by the middle of the 1950s. But in 1953 Stalin died and the deportation was cancelled. Despite some remaining Yiddish influences - including a Yiddish newspaper - Jewish cultural activity in the region has declined enormously since Stalin's anti-cosmopolitanism campaigns and since the liberalization of Jewish emigration in the 1970s. Jews now make up less than 2% of the region's population.13 Collective farm (in Russian kolkhoz)

In the Soviet Union the policy of gradual and voluntary collectivization of agriculture was adopted in 1927 to encourage food production while freeing labor and capital for industrial development. In 1929, with only 4% of farms in kolkhozes, Stalin ordered the confiscation of peasants' land, tools, and animals; the kolkhoz replaced the family farm.14 Podol

The lower section of Kiev. It has always been viewed as the Jewish region of Kiev. In tsarist Russia Jews were only allowed to live in Podol, which was the poorest part of the city. Before World War II 90% of the Jews of Kiev lived there.15 Campaign against 'cosmopolitans'

The campaign against 'cosmopolitans', i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. 'Cosmopolitans' writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American 'imperialism'. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors' Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin's death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against 'cosmopolitans'.16 Doctors' Plot

The Doctors' Plot was an alleged conspiracy of a group of Moscow doctors to murder leading government and party officials. In January 1953, the Soviet press reported that nine doctors, six of whom were Jewish, had been arrested and confessed their guilt. As Stalin died in March 1953, the trial never took place. The official paper of the party, the Pravda, later announced that the charges against the doctors were false and their confessions obtained by torture. This case was one of the worst anti-Semitic incidents during Stalin's reign. In his secret speech at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 Khrushchev stated that Stalin wanted to use the Plot to purge the top Soviet leadership.17 Erenburg, Ilya Grigorievich (1891-1967)

Famous Russian Jewish novelist, poet and journalist who spent his early years in France. His first important novel, The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurento (1922) is a satire on modern European civilization. His other novels include The Thaw (1955), a forthright piece about Stalin's régime which gave its name to the period of relaxation of censorship after Stalin's death.18 Communal apartment

The Soviet power wanted to improve housing conditions by requisitioning 'excess' living space of wealthy families after the Revolution of 1917. Apartments were shared by several families with each family occupying one room and sharing the kitchen, toilet and bathroom with other tenants. Because of the chronic shortage of dwelling space in towns shared apartments continued to exist for decades. Despite state programs for the construction of more houses and the liquidation of shared apartments, which began in the 1960s, shared apartments still exist today.-----------------------