Meyer Goldstein

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskya

Growing up

Our religious life

My school years

Continuing my studies

During the war

Post-war

I was born on December 5, 1916, in the town of Korsoun-Shevchenkovsky, formerly in the Kiev province and currently in the Cherkassy region. Back in 1916 this town was called simply Korsoun.

The name of my mother’s father was Ariy Voskov; my grandmother’s name was Feiga. My grandparents came from Taganchi, a small Jewish town not far from Korsoun. At the end of the 19th century, after a pogrom, those who could flee, fled. My grandparents fled, too. Their first daughter had just been born, but on their way she caught cold and died. After that, in 1895, my mother, Sonya Voskova, was born in Korsoun.

In 1898, her sister Ita was born, then Vekha in 1902, Esther in 1907, Golda in 1909, and brother Munya in 1912.

Munya was a very gifted musician. All the girls received only junior education. Under Soviet rule, my mother, Vekha, and Golda worked in an artel of handicraftsmen as confectioners. Later, Vekha married a printing plant worker and went to live with him in Cherkassy. Before the war Golda left for Kiev and worked in a newspaper. Ita lived in Korsoun.

I grew up practically without a father, because soon after my birth, my father got ill, and then died when I was three months old. He got gangrene; his leg was amputated.

My father, Isaac Goldstein, was a confectioner. He worked under somebody else. He did not have his own business. He had no education. My mother told me that he was a religious man who went to synagogue, kept holidays and traditions, and prayed.

My father had brothers. His oldest brother Leib was a tailor. His second brother Menakhem was also a confectioner. My father was the third brother, while the fourth brother, whose name I don’t know, moved to America in approximately 1916. He died there in 1941, leaving a fortune in inheritance. In America he was a lawyer.

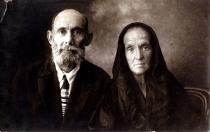

I never knew my father’s father. He was already dead when I was born. My father’s mother Rukhlya was alive and lived with her middle son Menakhem in Korsoun. They had no house of their own, but rented a tiny flat. The flat had only two little rooms. The first was occupied by my grandmother, while Menakhem and his wife Lea slept in the second one, which was bigger. I don’t remember that flat very well because I was there only several times when I was very young.

My grandfather Ariy Voskov became a father to me. My mother and I lived in his family, and I, just like other children, called him “father.” He made hats. He had a lot of orders, but we were poor, very poor, because not many people paid for his work. We never had a house of our own, we always rented. We often moved from house to house trying to find something cheaper. Usually we rented poorly furnished, cheerless flats with iron beds. All our family usually lived in two rooms. My grandfather would work in one of these rooms. I remember big wooden models, on which he pulled hats and great irons in our house. Grandmother did all the work around the house, cooked, cleaned, and raised children. She worked from early morning to late at night. She had to feed everyone, bring water from the yard, heat the oven, clean the rooms. Salaries were low and we did our best to survive. I remember when I was in the third grade stores began to sell very cheap toy pistols. Three days I spent crying before my mother. I will always remember it. I cried and begged her to buy one for me. But she… it’s not that she did not love me, but we were so poor… that thing cost 20 or 50 kopecks, but she could not tear this money away from the family. Those were Soviet times already, and my mother was working at the “Red Confectioner” artel. Her sister Esther also worked there.

When I was three or four years old there was a pogrom in Steblev, not far from Korsoun. Gangs would burst into Jewish houses, kill men and rape women. I did not understand what a pogrom was then, but later I understood it, when I saw how one woman was raped. Later she lived not far from us. She never got married and she had mental problems afterwards. During the pogrom my mother took me and fled from the town, together with one of her sisters.

My grandfather, Ariy Voskov, was a very religious man. Every day, morning and evening, he went to the synagogue. He put on his taleth and tefillin. No matter whether it was a work day or a day off, every morning and evening he spent in the synagogue.

We celebrated all religious holidays at home. I remember Passover. We brought all crockery down from the attic, and we always had very nice kosher crockery. All the family would sit around the table, and we cooked everything that had to be cooked according to the Hagaddah: eggs, one potato each, fish, chicken, horseradish, and matzos. Grandfather would lead the seder. This holiday I remember, but I don’t remember any other holidays.

As far as I remember, around 90 percent of families in Korsoun were Jewish. Two streets crossed downtown: Shevchenko and Lenin Streets. On one side there was the Ros River; over the river was a machine building plant, and dye-works. Then there were the smithies. The blacksmiths were all Jewish.

Most Jews in the town were craftsmen and traders. Craftsmen included tailors, hatters, shoemakers, roofers, and balaguls, those who had horses and carts, and took people to and from the train station, which was about five kilometers away from Korsoun. During Soviet times, all handicraftsmen united into an association called Shveinik, meaning “sewing industry worker.” All of Shveinik’s members were Jewish. This artel included my mother’s sisters Vekha and Golda as well as many other people whom I knew. Moshka Ocheretik was a craftsman. He led the self-defense unit of the Jews who defended the population from gangs during the Civil War. Jews were all on friendly terms. They helped each other and defended themselves. And the Jews of Korsoun had good relations with Ukrainians. Many Ukrainians even spoke Yiddish as well as their native language.

The central streets of Korsoun had stone paving. In the very center of the town there was a market place and a big square with four synagogues. The largest synagogue was beautiful, made of stone, with nice big entrance over the steps. I remember it very well because my grandfather would go there and take me with him. On the first floor, where all the men stayed, there was a big hall with wooden benches. At that time I did not understand what those people and my grandfather were reading, and I was not interested in it. My mother and her sisters would go up to the second floor, but they went to synagogue only on holidays. There were three more synagogues in the town, but we never went there, so I don’t remember what they looked like.

Another picturesque area was Pomestiye, located on two islands on the Ros. There was a beautiful castle there, and waterfalls. There was also a very nice church. I still remember the sound of its bells and can sing it to you. For instance, when the service began, the small bell started – bong-bong-bong. Then, Bong! went the big bell. The church was very close to our house and I remember exactly what the bells sounded like. I can tell you for sure that I liked this church more than the synagogue then.

But in 1932 this church was ruined by order of the communists, because the country began to persecute religions.

And synagogues were closed down. Only one was left. Our synagogue, the most beautiful one, became a youth club, where youth and Komsomol members got together for their meetings. A Jew named Boguslavsky was its director. The second synagogue became a sewing workshop, and the third one simply stood empty. The smallest synagogue remained functioning. I don’t remember any manifestations of anti-Semitism in those years; it was the general state policy to close down all religious buildings. I remember it very well because I was 16 years old at that time.

I was attending a seven-year Jewish school. All the subjects in it were taught in Yiddish. Most of all I liked mathematics and physics – I liked both subjects and their teachers. We also learned the Ukrainian language and literature, and the German language. Teachers of the Ukrainian language and literature were Ukrainians, while the rest of teachers were Jewish. It was a secular school for Jewish children, for whom Yiddish was the native language. We had no special Jewish subjects at all; Yiddish was simply the language of instruction.

I remember the major Soviet holidays: May 1, October Revolution, Paris Commune Day. On those days we went out to demonstrations together with adults, carried red flags, and enjoyed it very much. My grandfather Ariy never welcomed the revolution. He never celebrated any holidays except the Jewish ones. My mother and her sisters, like most Jews of their generation, were quickly assimilated and joyfully received the new order, believing in the Communist ideas. During the war my mother joined the Communist Party.

When I was in the fourth grade I joined the young pioneers. But my grandfather wanted me to attend the rabbi’s classes! So, I attended the rabbi’s classes at his house. Well, you know, we would sit at the rabbi’s, he would read to us and we would repeat after him. Later the rabbi complained to my grandfather about me, because I once met him in the street and saluted him! I saluted a rabbi like a communist pioneer! The rabbi got very upset and told my grandfather, who became indignant with me. But still, I remembered some of what the rabbi taught us. So, I knew Yiddish but never learned Hebrew very well.

At school I got very interested in electricity. All the lamps, chandeliers, and sconces that you see here in this room were made by me. I had always wanted to become an electrical engineer

I never thought I would become a teacher, but my fate went such a way that I found myself in the teacher’s institute. It happened so that after graduation from the seventh grade we all went to Nikolayev to continue our studies. There were eight of us, all Jews, five boys and three girls. In Nikolayev there was a Factory Plant College at the Andre Martie Plant, which today is a shipbuilding plant. We lived in a dormitory. There were five people in our room. There was one toilet and one kitchen for the whole dormitory, where lived a total of approximately 60 people. We lived well, trying to help one another and our families. It was a military plant and we received good portions of food there. On top of our meals in the canteen, we also received bread cards to buy one and a half or two kilos of bread a day. So five of us put these cards together and sent our bread to one family a week, in turns. This way I helped my mother to survive, because by then it was 1933, the year a famine was artificially created by the government.

Life was very hard, especially in villages. Young Ukrainians would go to the cities every morning to look for jobs to somehow feed their families and survive. Everyone’s life was hard.

Among my friends in Nikolayev was a girl, Anya Yakobson. We came from Korsoun together. I always cared for her, all my life. We were friends, then we dated…. One of her relatives from Nikolayev said that the Odessa Pedagogical Institute lacked students and we could try and enter it. So the whole group of us left Nikolayev for Odessa. We had nothing when we left. We did not even take our documents from the College.

In Odessa we were told that we could not be accepted without documents, so we were sent to the Worker’s Department (an institution of learning created by the Soviet authorities for youth without full school education). There we had exams. Only one other boy, Izya Kotlyar, and I passed those exams and were accepted to the third year, while the rest had to go home. In 1934 he and I studied at the Workers’ Department and then transferred to the Odessa Pedagogical Institute. I chose physics and mathematics because I liked them and also because at our school we had studied in Yiddish, so we did not know other languages well enough. We lived in a dormitory and were paid scholarship, but it was not enough. It was thirty rubles plus some kopecks. That is why, even though I was a Komsomol member then, I did no public work. I was never an active Komsomol member, I simply had no time for that. I worked at a bread store: at night I would bake bread, and during the day I would study at the Institute.

In our dormitory there were young people of various nationalities from different places – Russians, Ukrainians, Tatars, et cetera. I was on good terms with all of them. We never divided people by nationalities. Life was hard for everyone.

At that time arrests and what became known as the Stalinist arrests and show trials began. My mother’s brother Munya served in the army leading an orchestra, for he was a very gifted musician. But he lacked self-control. Once he did not like the food they were given and said so. He was arrested. That’s all. He disappeared. We could not inquire about his fate. No one would answer such questions.

In the beginning of 1939 I graduated from the Institute. I was sent to the town of Pikov, a Jewish town in the Vinnitsa region. Then in the fall of that year, the Germans captured Poland, and our troops entered the Baltic countries and western Ukraine. The country was on the verge of war, but few realized it.

I was summoned to the military registration and enlistment office. They sent me home, to Korsoun, and ordered to wait for a call-up. So at the end of November we were taken to the Leningrad military district. The Finnish War began.

We found ourselves in barracks in Gatchin. It was extremely cold, about 50 degrees Centigrade below zero. All we had were summer uniforms. We had three-story plank beds. There were so many people that at night we could turn only on order. In the morning all of us were taken outside for physical exercises. Many of us were from the South and were not used to cold. So the second day many got sick, including me.

Relations in the army were friendly. Nobody offended me as a Jew. On our way there in the train some people laughed and made Jewish jokes, teasing me, but in my military unit nobody did that. I was respected.

I was put in a signalers’ platoon. One day we were walking, choosing observation posts. A lance corporal was walking in front of me. We had to follow a narrow path because everything around us was mined. He was must have been distracted by something because he stepped to one side. Immediately there was a terrible explosion. I ran to him and saw that he lost his leg completely. That was the end of his fighting. He was rushed into hospital and I heard nothing else about him. There were many victims in the Finnish War.

After the end of the Finnish War our division was sent to Tbilisi. The year was 1940.

I worked at the headquarters because I dealt with communications. It was May 1941. Since I had higher education, they offered to let me prepare and become an officer. They planned to make me a junior lieutenant and transfer me to the reserve. So on Saturday, June 21, 1941, I passed my exams for lieutenancy. And on Sunday, June 22, when we were at the training range, the Second World War began. We were put on platforms and taken to Makhachkala. There we were stationed for all of 1941 and almost all of 1942. I was lucky there, I got in touch with my mother. She was in Yangiyul in evacuation, and she got married there. She had known her second husband, Shlyoma Sklyar, even before the war, because they had worked together as confectioners. On their way to evacuation his wife died on the train, and my mother became his close friend.

Many people could not survive evacuation to the east. My mother’s sister Ita was in evacuation together with her in Yangiyul, and there she died from cold and starvation. Her sister Vekha got married before the war and lived outside Cherkassy. She had a daughter. During evacuation they ended up somewhere else far away, and the girl was run over by a car in front of her mother. Vekha’s husband could not live through that and committed suicide, so Vekha was left alone.

Esther was in Magnitogorsk, working at the canteen of a military plant.

For women, evacuation was extremely hard to bear. They worked for themselves, for their brothers, for their husbands, and devoted everything to the soldiers. They did not eat enough or sleep enough. Coming from the south of Ukraine, they froze in Siberia, but they did everything in their power to advance our victory.

Golda, my mother’s youngest sister, had the best education. Before the war she was an active Komsomol member. She worked in a Komsomol newspaper in Kiev. In evacuation she ended up in Sverdlovsk, caught cold and died there.

Almost all of my relatives were evacuated to the east. Only my father’s brother Menakhem and his wife did not want to be evacuated for some reason. Later, when the Germans were very close, he, his wife Lea and my grandmother Rukhlya went to Krasnodar. My grandmother died on the train and was buried right there by the railway. Menakhem and Lea lived for about six months in Krasnodar before the Germans entered, gathered all the local Jews and those who had fled there, thinking they had gone far enough, and shot them.

I don’t know about the rest. Izya Kotlyar also fought and survived. I don’t know where he is now. And I lost my Anya Yakobson during the war, I lost all trace of her, ah.…

My mother’s parents had died before the war.

My mother came to me in Makhachkala. I found a flat for her. When she came, Regiment Commander Damayev, who came from a famous Russian family of actors and who treated me very well, helped get food for her. Later, when the Germans began to bomb Makhachkala, I sent my mother away. I took her to the port and sent her away because we already knew by that time that the fascists killed Jews. However, the Germans never occupied Makhachkala.

We began to fight from Gudermes, the second largest city in Chechnya. The Germans had already occupied the Northern Caucasus, Krasnodar and Rostov, and reached Terek. And we began to take part in military actions in Gudermes. When we arrived there, the city was empty, there were no locals at all. Some locals, those who showed hostility towards the Russians, had been moved out by the authorities. But most of them went into the mountains.

From Gudermes I began to move westward with my regiment. We liberated Taman, then the south of Ukraine, Berislav (our division was called “Berislav”), Kakhovka, and many other cities and towns. We already knew about ghettos in the cities, about Jews being shot, about death camps. And right before the Soviet troops came into Nikolayev, which was close to my heart because I studied there, the Germans gathered all the young people so that they would not go to the Soviet Army. They told them they would be sent to Germany, and they shot them all at the train station. When we entered the city, they were lying there, all dead.

In general, there were no divisions between Jews and non-Jews or other nationalities during the war. In my regiment, the Battery Commander was Berdichevsky. The chief of the medical unit was Gleiman, and his assistant was a Jewish woman from Leningrad. She now lives in Israel. But in the headquarters I was the only Jew.

All were equal at war. All were in trenches, all were equally cold, lacked food, slept where they could and when they could, only in breaks between fights. We all wrote letters home and we were all killed equally, no matter what nationalities we belonged to.

Then we liberated all the capitals – Belgrade, Budapest, Vienna, and Prague. We ended the war in Prague and celebrated victory there. From there we were put on trains and sent to the Far East to fight against the Japanese.

The war ended, but they did not let me leave the army. My regiment commissar summoned me and said, “You will not be transferred to the reserves until you join the Communist Party.” So they forced me to do it. I was not ready to. In April 1946 I joined the Party, and in June I was demobilized.

I came to Kiev. I was called up in Korsoun, but I wanted to go to Kiev. Since I worked in the headquarters, they forged a document for me, to make it look as if I had been called up from Kiev. My mother was in Korsoun at the time.

Every year I went to Korsoun. All the Jews there were shot during the war. The last class of the Korsoun school, children who graduated in 1941, including my great-nephew – none of them returned from war. All of them were Jewish. Some of them were killed at the front, some were shot in Korsoun, and others were reported missing.

Many Jews were shot in Korsoun. Today, their remains have been reburied in the Jewish cemetery of Korsoun. A common grave and a tomb were created with an inscription that the Jews of Korsoun were shot there. But the Germans! What they did in Korsoun! They dismantled the house Menakhem had just built to get building materials. They put their headquarters in our Jewish school, and they paved the road to it with gravestones from the Jewish cemetery. They put these stones so that the inscriptions in Hebrew could be read. There I found stones from the graves of my father and grandmother. The Germans enjoyed stepping on Jewish names.

After the war I came to Kiev and worked as a mathematics teacher in various schools.

In 1951 I married Klara Matveyevna Zhitnitskaya, born in 1926. My wife comes from Korsoun. Our parents knew each other. Her mother, Makhlya Zhitnitskaya, was a tailor and worked in the tailors’ artel. Her family worked in Korsoun, and like all other Jewish families was assimilated, but they kept some holidays and traditions. Klara graduated from a pedagogical institute and worked as a teacher in one of the Korsoun schools.

We met during one of my visits to Korsoun. I think it was in spring. When we married it was a hard time. We did not have a Jewish wedding. Anti-Semitism was rising in our country. It had absolutely no influence on me at work. But in the streets, in lines, on public transportation, people would stare or tease. And there were articles in newspapers and pamphlets featuring typically Jewish names like “Abram Abramovich.” When you read, you immediately knew who you were reading about: if it was a Russian, his name was Ivanov, if a Ukrainian, Shevchenko; if Jewish, Abrashka, Surka or something like that. I guess the anti-Semites liked that.

By the way, my mother, who was a Party member, was summoned to the district Party committee and asked, “Why are you called Sonya? Your real name should be Sarah or Surah. You should bear your real name.” She could hardly get rid of them. Sneers continued for a long time. Not only the Jews as a nation, but also Jewish names were despised.

It was hard to find a job for the same anti-Semitic reasons. But the director of the school where I worked was very nice to me. He hired my wife as well, provided nobody would know that she was my wife. In those years, Soviet bodies of power forbade relatives to work in the same organization, especially if they were Jews. For several years we managed to conceal that we were spouses. For that reason my wife did not change her last name.

In the street people would ask me, “Where did you fight? In Tashkent?” Nobody wanted to believe then that Jews fought at the front and were killed just like the others who defended their motherland. When Stalin died, anti-Semites got quieter. But in general, anti-Semitism was always present in our country.

That is why we had no Jewish wedding. We continued to keep some Jewish traditions, but very quietly, in secret. On Passover we always had matzo at home. We bought it from the only synagogue that remained in Kiev, where people baked and sold matzo under threat of persecution. We also celebrated Hanukkah. I was born on Hanukkah, so it was a double holiday for us.

In 1952 our daughter Faina was born. We gave her a Jewish name. She was a cheerful and kind girl. She had friends of different nationalities, but she always kept her Jewish identity in mind. Immediately after graduating from school she married a Jewish boy named Ilya Kobernik. That is why she did not continue her education. She stayed at home, bringing up children and working around the house.

My wife and I continued to work at school until retirement. We have taught more than one generation of children. In 1996 my Klara died. I feel very lonely.

Despite the fact that life was hard we never thought of emigrating. My granddaughter Sveta now lives in Germany. My daughter with her husband and younger granddaughter are planning to move to her, so they are selling everything. They are leaving soon. I told them I’m not going with them. I am old and I want my remains to be buried here, in my motherland.

Times have changed now. Anti-Semitism is certainly hard to uproot. But Jewish life in Kiev and in Ukraine is very energetic now. Synagogues are working, as are Jewish cultural societies, including the Kinor Jewish community center, where I like to go.

I receive invitations from them and go to their meetings. But I don’t go to the synagogue, I’m not religious.

I receive aid from the Jewish community, from the Khesed charity center. I get food parcels, hot meals and Jewish newspapers. I like talking to old people. Basically, I’m not going to leave this land. This is all. Thank you.