Marcel Simon

Suceava

Romania

August 2006

Emoke Major

I met Marcel Simon at the Jewish community in Suceava, where he is a secretary. He is a calm man, who speaks very little, but concisely. Our discussion, which took place on a bench in a small park of Suceava, and during which he told me the story of his life only lasted for an hour. He was very nice, but I understood that he doesn’t like speaking very much, and especially not about his personal things.

My family background

I didn’t know my paternal grandparents, they died before I was born. My grandfather was called Bercu Simon and my grandmother was Lipsa Simon. They lived in the village called Slatina, Suceava county – before it was called Draceni and belonged to Falticeni. [Editor’s note: Slatina is 30 km from Falticeni to the west.] They were merchants, they had lands, they traded and were quite well off.

My father had a second cousin in Bucuresti, Bebi Leivi. She had two daughters, one of them was Rica.

My father had a brother in Cernauti. He was also Simon, but I don’t remember his first name anymore. He was a couple years older than my father, so he was born around 1900, since my father was born in 1904. He was an accountant. He had a family, one of his daughters was called Rita Simon, and her brother was Doliu Simon. I don’t know what happened to them. I think my father’s brother died before we returned from deportation, and we didn’t know anything about their family.

Father had another brother, Leib Simon, who had seven children. Five of them were buried in Falticeni. Three girls: Adela, Miriam and Rasela; and two boys: Lica and Licusor. They died at a young age, they were between 18 and 28 years old, – because one of them was a pressman and they contacted pulmonary tuberculosis from each other, they contacted the germ from each other. They died after World War II within 8-10 years. There were two other boys: Buma and Mendel, who emigrated to Israel. Buma left before Mendel, but he also died at a young age. He was an air-officer, and died in the first Arab-Israeli War in 1948. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Arab-Israeli_War] Their parents also emigrated to Israel, they died there. My last cousin, Mendel Simon, died 3 years ago [in 2003]. He was over 80. I saw him together with his wife 4 years ago. Mendel’s daughter, Miriam Kruger, still lives. She has two daughters and a son and lives in Rehovot [in Israel]. Her husband is called Baruch.

My father had two other sisters, Estera si Ruhla Simon, who lived in Suceava, they were single, the Jewish community from Suceava took care of them, and they both died in the same year, in 1975.

My father was born in 1904. His name was Herscu Simon, his Jewish name was Zvi – Hers means Zvi. Father had only completed elementary school. He did his army service in 1926-1928. He was a merchant.

My maternal grandparents lived in a village called Bosanci, 8 kilometers from here, from Suceava. My grandfather was called Leib Gingold, and he was a merchant and also had lands, just like my other grandfather. My grandmother, Leia Gingold died in 1939, she was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Suceava. My grandfather also died in Transnistria 1, in 1942.

My maternal grandfather had three sisters. One of them was called Sophie Gingold, and was born in 1888. She was a teacher of German and Yiddish at the Pedagogical School in Cernauti. Aunt Sophie wasn’t deported, she remained in Cernauti during World War II, and after the war she refuged here, to her sister Regina Weber, who had a house. She taught Talmud Torah and also Yiddish in Suceava. Aunt Sophie was a rougher woman. Being a teacher, she was stricter, she liked discipline, order. She helped us with our homework sometimes. She wasn’t married. Her sister, Regina Weber was married, then her husband died. Aunt Sophie and aunt Regina lived together. We had good family relations with them. We met and visited each other. Aunt Regina Weber died in 1970 at the age of 85, and in December 1975 Aunt Sophie also died.

These two aunts of my mother’s, aunt Sophie Gingold and Regina Weber had another sister, Janeta. She converted to Catholicism and lived in Bucuresti. She had two daughters, who lived in Bucuresti: aunt Ghizi [Ghizela] and aunt Lidi [Lidia]. Aunt Lidi had a son, his name is Puiu Droniuc. He lived in Bucuresti for a while and before the Revolution 2 he emigrated to Germany. I don’t know anything about him.

My maternal grandmother had a sister, who had two daughters, Ghizela and Loti Strominger.

My mother only had one brother, he was called Max Gingold. With his wife and a girl he left Romania in 1948 with the help of the Frenkel family, a rich family from America. He wanted to emigrate to America, but I don’t know for what reason he couldn’t enter in America, and he stood in Cuba for 2 years. My aunt, her name was Hava, died there when the girl, my cousin, called Tamara Gingold, was 8 years old. My uncle was badly off at the beginning. Then he lived with a woman, she was Jewish, but they didn’t get along, and divorce wasn’t legal in America, so he only managed to divorce her after I don’t know how many years. He got to Canada with the help of some acquaintances from Bosanci and became a small retailer. He lived in Engelhart, s very distant city, at about 1000 kilometers from the polar circle. Uncle Max died in 1992.

My cousin lives in Toronto, she was a teacher all her life, and now she is retired. She divorced from her first husband, who was a lawyer, and has another husband now, her last name is Moscow now. Her children are adults, about 35-40 years old. Her son graduated a journalism university, he was a photo reporter in Japan. Her daughter lives in France, she is also a teacher as far as I remember. I don’t know my cousin’s children, I never met them. I wouldn’t recognize her either. She was on a trip with her husband in Israel for three weeks, and they called me at that time and I spoke with her a little in Yiddish. She also speaks Yiddish. You know, when you learn something in your childhood, it becomes part of you, wherever you would go, you still don’t forget it. But I haven’t seen her since 1948. You can imagine, she was 8 years old when they left. She is a bit younger, I was born in February and she was born in November. She was supposed to come to Romania next year [2007], but with an interpreter, with my brother’s daughter, who is a stewardess and speaks fluent English. My uncle from Canada had been in Romania a couple of times. He came and visited Bosanci and the people with whom he had spent his childhood. Last time he was in 1988, when he was about 83 years already, and met people whom he hadn’t seen since he had left.

My mother was Sidonie – Sidi. She was born in 1906 in Bosanci, completed four classes of elementary school.

Growing up during the war

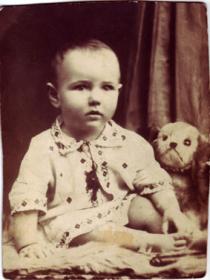

I, Marcel Simon, was born in the village Bosanci on the 23rd February 1940. My Jewish name is Mendel. They called me Marcel in the family. I only have a brother, his name is Benito Simon, but they call him Beno. My brother was born in Suceava on the 28th July, 1941, he is 1 year and 4 months younger than me.

From the 9th October 1941 until 15th April 1945 we were deported to Transnistria 1. So if the deportation was in October 1941, I was one year and 8 months old, and my brother was younger than 3 months. We were in a place called Sargorod 3, together with my parents, my brother, my maternal grandfather, my uncle Max Gingold and his wife and daughter, my aunt, my cousin and my mother’s two cousins, Ghizela and Loti Strominger, and hundreds of other Jews.

My father told me what I am telling you. What can a one and a half years old child remember? I don’t know what we lived of. We got some support from different places, they worked by the day. Mr. Pietraru, our former president of the community told me, he was 20 years old, he worked at a flock, had different jobs. But there were very difficult circumstances, lice filled us, people died one by one, because of the misery, froze to death, starved to death and died of illnesses. There weren’t medicines, illnesses cut down the people. My father suffered of petechial typhus, he lost his toes, became handicapped.

Then there were the bombings when the German army passed, because the Russians were a couple kilometers behind them. And my father told me that there was a horrible bombing at that time, when everyone pulled back. We couldn’t hide, both my father’s legs were wounded, we were small children, and then he said: ‘Come what it may!’ And father told me that a German came in, I was small, blond, he took me in his arms and he started to cry and said that he had a child just like that at home and that the war was cruel and cursed. There were humans among them, too, not all the German army was made up of SS.

After the war

After the war we were badly off, because the communist era started, and you weren’t allowed to… [trade]. These were other times. And since my father didn’t have much schooling, he had various jobs. He worked in the commerce, was a night-watchman – odd jobs, so that he could raise us. My mother was a housewife. She dressed according to the fashion of that time. Modestly. At holidays a nicer skirt, a blouse, father wore a suit. Sometimes she bought us a new pair of trousers, new blouses, scarves or caps. My mother was just like the other mothers. She was very kind, she took care of us. Father was a stricter person, but he was very good-hearted and he cared for us. I remember that where we spent our childhood there was a hill, there was a slope until the foot of the Citadel and we sledded. But father kept on shouting: ‘Stay only an hour outside!’ And we, with the boys and girls forgot to come. Father came to us, he slapped us on the face, he reprimanded us. But what happened? Because we were warmed up, perspired and drank cold water and we got tonsillitis immediately…We almost suffocated. And I remember that father ran to dr. Weitmann during the night, he was a very good doctor. And we had to stay at home in warm, and got penicillin shots…that made us feel better in some time. But at that time there were really four seasons: winter was winter and summer was summer. Now everything has changed.

They brought us up well. Many times too well. Because in life sometimes it isn’t good to be too correct, too honest. True, these are good qualities, but many times they don’t help you! Because life is tough and you have to know to get on. Because that’s how life is. Now in our country there are rich people, very rich, we can say. But nobody knows the way they had made their fortune. And you aren’t allowed to accuse anyone unless you have evidence.

My parents didn’t want to go to Israel. I don’t know why my father didn’t agree to leave, he hardly supported heat, and when he heard what [temperature] was there, he used to say ‘I can’t live long there.’ And really, many people didn’t adapt there.

Most of the population in Suceava is [Christian] Orthodox, but there are Catholics, too – there are over 1000 Catholics. Among the Catholics there are the Polish, the Hungarians, there are Calvinists among them, too, and there are some Armenians and Ukrainians. But the relationship between the different nations has always been good. In the communist era, what can I say, we all suffered the same way. We all stood in queue, we lived though hard times when they gave bread on ticket.

Before World War II there were 5000 Jews in Suceava, after the war 2000 remained. So I did catch some [Jewish life]. In Suceava most of the Jews spoke Yiddish. But many spoke German as well. For example, if a Jewish family met a German family they spoke fluent German with each other. We spoke Yiddish at home. I learned German through the contact with the rest of the world. But I knew Romanian too, because this is the base language. Mrs. Salinger, who works at the Jewish community, being from Cernauti, says that most of the people there spoke German.

As I child I went to a Jewish school, to cheder. Normally one went to cheder before school, but I went from 1946, after we returned from Transnistria. In the cheder we spoke Yiddish and read in Hebrew. I knew Hebrew really well. I don’t know it anymore, I forgot. I learned 3 or 4 years with a religion teacher, as it was customary at that time that people learned parts of the Torah. I remember that my teacher was an old gentleman, and we played, we fooled about, and he ran after us, he slapped us sometimes – in a friendly way. We started with the alef, bet – with the alphabet, and then the parts. We had to sing… It was a nice period! Even though times were tough and we were poor children. I don’t know anything of it, because I didn’t practice. You know how it is, a language can be learned by communication with people, not by memorizing and reading word by word. More than 60 years have passed since than, and I don’t remember many things from the cheder. But anyhow, there were many children, we were in groups. In a group there were 25-30 kids, just like a quite big class. Only boys, there weren’t any girls. Now, in the more modern period, even the girls went to the Talmud Torah. Mr. Pietraru, the former president of the Jewish community in Suceava told me, that even girls went, there are some pictures of it at the Jewish community.

I had a colleague and very good friend- Avi Haber. He is of my age, we spent our childhood together and we went to school together. He emigrated to Israel in 1964, he lives in Qiryat Tiv’on, close to Haifa. I saw him 4 years ago when I was in Israel for the third time. He was a Colonel of Justice and retired, but he still works. He is married, his wife is from Vienna and has three grown boys. Another Jewish friend I had is Manas Sica, who lives in a town called Qiryat Motzkin, has three daughters, but they never came back ever since they left.

In my childhood traditions were observed, though my father wasn’t an extremely religious man and there were difficult times, there were times after the war. My mother wasn’t especially kosher, but she observed what she could.

We observed Sabbath as we could. I remember that mother bathed us both, dressed us nicely and made a coilici [Editor’s note: Coilici is a variant for challah, similar to the word “kajlics“ used by some Hungarian speaking Jews in Romania. Both words have the origin of the Hungarian word “kalacs“.] – a challah, which is made for Sabbath –, lit two candles, said a prayer, father did the blessing, and then, since it was a holiday, we had a better meal, once a week. I remember that on Friday evening she made us some meatballs and after that she made a pudding for desert out of vermicelli with nuts and sugar, then my brother and I fought each other to clean out the bottom of the pan, because it was very delicious.

Father went to the synagogue, but only rarely, at the high holidays. He also took us to the synagogue on the high holidays. I remember Yom Kippur. It is very difficult on Yom Kippur, it [the service at the synagogue] starts in the morning, it lasts until 1 or 2 PM, and after that, with a break of 2-3 hours there is the closing. On the evening before that the Kol Nidre is recited. On Yom Kippur we, the children also fasted with our parents. When we were small we only fasted for half a day, but after the bar mitzvah we fasted properly. And at Rosh Hashanah we all went to the synagogue, and I remember that they blew the shofar. We have a man now, Mr. Zighi Blaustein – who blows the shofar on holidays, he used to be a drummer, he was never married and is 85 years old.

We observed the Pesach. We were poor at that time, we didn’t have possibility to get all new pots, as it was customary. During the Pesach one had to cook everything in new pots. Mother boiled them [the ones which were used every day] with lye wash, she made the lye wash out of sand and stone, she boiled them well, cleaned them and washed them. We tidied up the house, we lived in a house, gave the wall a coat of whitewash so that it would look clean, and she bought us each new clothes, as the possibilities allowed it. We had matzah. At that time azyme was made here too, now it comes from Israel. Now all these are tales, because very few observe the Pesach in a traditional way.

I don’t remember a Seder from my childhood. We observed it with my father at home, but I don’t remember, I was too small. One ate bitter herbs and matzah, made eggs. During the Pesach more eggs and potatoes are eaten, because it isn’t allowed to eat leaven. They made a kind of ‘ciorba de perisoare’ sour meatball soup made of matzah flour. And out of the matzah flour keyzel can be made too– a kind of ‘tocinei’ [similar to the Kartoffelnpuffer or latkes], but sweet. We bought wine from the community. We observed the Seder at home until I was in high school, until 1950 or so. But Seder is observed in fact in a larger community, at the Jewish community. But I have never attended.

I don’t remember Purim. I had bar mitzvah here in Suceava, but I really don’t remember that.

My brother and I went to school, to high school, just like the other kids. In 1956 I graduated from ‘Stefan cel Mare’ High School, here in Suceava. I graduated the 10 grade high school, it was so at that time. I took the entrance exam to university two times, I failed, and then my father’s illness came and I had to get a job, to earn money and support the family. Later I took the difference exams and I attended the Commercial High School and graduated in 1973. And from 1958 I worked for 40 years as an accountant at the Burdujeni Abattoir – Burdujeni is a district of Suceava.

In the meantime, my brother graduated high school in 1960. He also graduated from ‘Stefan cel Mare’ High School, but of 11 grades, and went to Botosani, where he finished a commercial technical school. And after that he enrolled to I.S.E. [Institute of Economical Studies] in Iasi, but he didn’t graduate, he completed 3 years and in the 4th year he emigrated to Israel, because of his friendship with his actual wife, and she had left earlier with her family –, and they got married. His wife, Pepi Malvina Simon, was born in Falticeni in 1950. And my brother worked in Botosani, he was an accountant in the industrial field, at the wood works – nothing has remained of that. After he enrolled to go to Israel, he was fired, that’s how times were, he worked for a while as a worker, and in October 1970 he emigrated to Israel with my mother. My mother said that she liked it there. She got used to being there, she took care of the girl, of my brother’s daughter for a while, when she was small.

In Israel my brother was very badly off at the beginning. He stayed at a hotel for a while, as it’s customary for the newly arrived. After that mother remained there, but he had to leave to work. He worked for some people, who took advantage of him. After a while his bosses saw that he was a smart and serious boy, and that he could handle things and worked, and little by little they promoted him. He was very talented, and a few years later he became the chief accountant of one of the factories. Because this concern, Isra Beton, – it is a very big construction company, the third biggest in Israel – has very many factories. And it went well, but because of the war and the actual situation there aren’t many constructions. But he is 65 years old and has 3 years until retirement. He has a 34 years old daughter [born in 1972], Ayla Iavetz, who is a stewardess at El Al. Her husband is from Argentina, but he was raised in a kibbutz. He used to be an officer, he left the army and now works at a company as a jurist. They also have a grandchild, an 8 years and a half old boy [born in 2003].

I have never been a party member, nobody asked me to enroll. Since I had an uncle in Canada I did the army service in a forced labor battalion unjustly- it was a foolish thing from behalf of those at that time. Those who had relatives abroad, who didn’t have a healthy social position etc, were persecuted. Just consider this paradox! This uncle from Canada really did bad to our file, my brother did his army service in Targu Mures at a normal unit, and I at a forced labor unit. He was the first to do his army service. We went one by one, because the other one supported the family, because my father had become ill in the meantime. And after he came home I left. My brother finished his army service in 1964, I left in 1965 and returned in 1966. I stayed 16 months, that’s how long army service was. I was at a railway unit. I was lucky to be an accountant by profession and I got on, because there were very difficult times. I worked at the accountancy. Our unit had made services with the soldiers, who were paid by the army. And I can say that my situation was a bit better. But the soldiers who worked caught really bad times. They worked at the Iron Gate [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron_Gate_%28Danube%29], accidents happened, trouble happened, there were better and worse officers… and that’s how it was!

I went in the army from the Abattoir and when I returned they employed me there again. The company was about to go bankrupt in 1997, and since I had worked enough years, though I wasn’t of retiring age, I retired voluntarily. And I got unemployment-compensation for 9 months, and a compensation of about 16 millions. That compensation is a story in itself… It had been in banks, the bank went bankrupt, and after a year or so I got the money back. And from the 1st March 2000 I retired.

After a year [in 1998] I was asked to come and work at the Jewish Community in Suceava. And from then on I have been at the Community, I was a secretary and accountant, now I am a secretary. This is the story of my life – as one would say...

I got married here in Suceava. My wide, Aurica isn’t Jewish, she is Christian, she was born in 1943 in the village called Pomarla, in Botosani county. [Pomarla is 55 kilometers north-east from Botosani] She graduated the medical technical high school in Iasi and worked as a nurse and now she is also a pensioner. I don’t have any children. My wife has a married daughter who lives in Bacau, she is an engineer, her husband is an engineer as well, and they have two children.

I have gone through many difficulties: I remained alone here, my house has been demolished, I have been married before, she was also Romanian, I have gone through a divorce and many other things…And practically I dealt with funerals. I arranged my father’s funeral, aunt Sophie’s funeral, her sister’s, other two aunts’ from my father’s side, Estera and Ruhla Simon, and another two cousins’ of my mother, Loti and Ghizela Strominger, they were also old, who were supported and who didn’t have anyone. And I am a kind of a grave mourner – as it seems. And at the Community I also deal with this, and it’s not too pleasant. There was someone recently whom I arranged and the cleaning woman, because he didn’t have anyone.

My father died on the 18th February 1969 at the age of 65. He suffered very much, he had a deformed arthritis. But he had a lion’s heart. He was buried here in Suceava. At that time there were Jews in Suceava and he had a normal Jewish funeral. The windows and the mirror are covered and the dead is put on the ground with the feet towards the door until they come and put him in the coffin. [Editor’s note: Most of the actions that follow the moment of death have as their background different beliefs, which didn’t only emerge in the culture of the Jewish nation. It’s a cultural anthropological fact that there are common customs, which the different nations share. At the time of death it belonged to the first tasks to open the window, stop the clock and cover the mirror. The window is opened so that the soul that is leaving should have free passing. The role of covering the mirror was so that the dead wouldn’t see himself (his soul leaving the body)- this would make leaving more difficult for him. All three actions, in similar form and explanations spread all across Europe. Ethnographical Encyclopedia, (death article).] There was a man from the Community, who used to come and wash the dead and clothe him. He dressed in cerecloth, as they dress him nowadays, too. It’s not the way it is at the Orthodox, where they usually dress one in good or new clothes. Cerecloth is made of white linen, a pair of trousers and a shirt are made, and over it, on the head a cloth is put, which covers the eyes. For those who were believers they put the tallith, too. And then they put him in the coffin. They keep the dead at home. But you know how it was: you die today, and within 24 hours at most, they bury you. We made the coffins. They aren’t normal coffins. They have to be made out of unplanned fir plank, they have to be dry like a box, and it is narrower at the feet, just like a man is. Nails are used, metal nails, because the coffin is closed. At that time there was a hearse, a carriage with a horse, which was owned by the Community, and the dead was taken to the cemetery with that. My brother and I, I remember, went in front of the dead and prayed in the cemetery. And women are buried next to women, and men next to men. The wife is next to the husband, but on the other side of the woman another woman is buried, not a man. And next to the man, another man. At the Jews there isn’t any kind of burial feast, as it is customary at the Orthodox. And the one who performs [the funeral] cuts the clothes of the relative of the dead, and you have to wear those clothes for 8 days. Practically he doesn’t cut it until it tears, it’s something symbolic, it shows that you have lost someone and a piece was torn from your soul. And men aren’t supposed to shave or had cut their hair for 30 days. And you have to sit 8 days on the floor [E.M.: In Moldova I met the custom of observing eight days of shivah instead of seven days.], to wear only socks, and you aren’t allowed to leave the house, someone else has to do the shopping for you. This was possible once, but now it is very difficult. We couldn’t observe shivah, as it should be observed for 8 days, we observed it intermittently– we had to go to work. And after this 8 day period is over, after you had observed shivah, for 11 months you have to come to the synagogue every Saturday and recite the Kaddish – commemoration for the dead. I didn’t go because I couldn’t, I was at work. All these can’t be observed anymore. After 30 days a small ceremony is made at the synagogue, a kind of requiem, some prayers are said and challah and some drinks are brought to the synagogue. After a year, during this time the earth sets, you have to make the monument, to put a stone on the grave. A stone is made with both Romanian and Hebrew inscription.

I wasn’t at my mother’s funeral, because she died in Israel. She died at an old age home, because that’s the custom there. There is a custom there, which we don’t understand: the old people, who can’t take care of themselves, go to an old age home voluntarily. My mother lived in an old age home in Netania for a couple years. In 1983, when I was there with my brother and I visited her, I left with a bitter feeling. I said: ‘How come? She raised two children.’ In our country it is so: you raise three-five children, but in the end one of them takes it on and takes care of his parents until their death. In Israel they don’t. My brother said: ‘No, parents here become the children’s burden’. But I couldn’t reconcile with the idea that she died at an old age home. My mother died at the age of 79 in 1985 and I only managed to light a candle at her grave 4 years ago, in 2002. She was buried in Holon. There is a cemetery as big as a quarter of a city. It is a very big cemetery, and it is very well kept. They have all the information on computer. If someone from abroad comes and looks for a grave, they know it exactly, the row, everything.

I commemorate every year my mother’s and father’s death, they are two weeks apart. Usually Mr. Pietraru, who used to be the chairman, performed, and in the second part he prayed for the dead. And then I bring to the synagogue a ‘lechec’ [lekakh] – a kind of cake made with nuts or with honey, a milk-loaf, and a small bottle of alcoholic drink and some soda or mineral water. And I give a donation. The money goes to the community, because these are the sources of income of the Community. We don’t really have sponsors, because we don’t have many businessmen, and the income comes from community members’ fees, and contribution fee is received when the matzah is brought for Pesah, and at the fall holidays other donation.

When I go to the cemetery I light a candle for my father, I have two aunts here, aunt Sophie and her sister, I light for everyone from the family. They say that it’s even a bigger act of charity to light for a stranger, at one who doesn’t have anyone, because if you don’t light a candle for a relative you can go another time and do it.

The only thing I still observe from the tradition: on Friday evening I light two candles, two candlesticks, as it is customary. The only holiday I observe is Yom Kippur. Especially since my father died, he died in 1969, I really observe Yom Kippur. We go to the synagogue and I fast, I fast 25, even 26 hours. [Editor’s note: The fast starts at sundown, and ends on the next evening when the stars appear, it is usually a 24 hour fast.]

While I worked I practically didn’t have the possibility to go to the synagogue, because I worked on Saturdays. I worked at an abattoir, in which they worked for export, and we had to come to work even on Sunday [Saturday wasn’t enough]. And as the party was involved in everything, you couldn’t say no, they would have kicked you out at once. And one couldn’t observe the holidays. Older people who were already retired observed them. During the communism it wasn’t forbidden for Jews to go to the synagogue. Even though at the [Christian] Orthodox they said that it was forbidden for those who were members of the party, but even so, more discretely, they celebrated the holidays. They went to the Sfantul Ioan Monastery, opposite from my place, and celebrated Easter. And some took refuge at monasteries so that they wouldn’t be seen.

I go to the synagogue more often since I have stopped working and since I have been active within the Community. And we are kind of obliged to do so practically because of the nature of our position. There are other men in Suceava, but they don’t come to the synagogue. And you can’t force someone to go to the synagogue, this is a matter belonging to everyone’s conscience. But if you do believe in God and you want to pray, you can even pray on the mountain top, as they say. But in my opinion it counts for one to take the responsibility for his own deeds... They say that you have to go to the house of God, where are more people, so that your prayer would be listened, but at the same time you also have to stop committing sins. I tried all my life to respect the moral principles. I don’t come from a very pious family, and not very cultured either, but my father taught us from the time we were small and we respected these: not to steal, to respect our bosses, to respect the leaders of the country, to respect the laws, not to do harm, not to denounce... And I respected these things and my conscience is clean.

From all my family, with all my family tree, I am the only one who remained here in Romania. I was born here and I will die here, because at my age there is no point in emigrating. I would have some place to go, but it’s too late. I could have also gone to Israel. But I decided not to go, because I was convinced that I couldn’t have got used to living there, firstly because of the climate, and also the language seemed very difficult to me. Many people didn’t get acclimatized in Israel because of the language. My brother speaks it fluently, you can’t get a job otherwise, but he tells me that people are more modest, less learned, with less schooling, who have lived in Israel for 30, 40, 50 years and still don’t speak Hebrew [Ivrit] well. Not to mention writing… I was on good terms with my brother. We had a different temper. He was a little bit more nervous, he smoked. I resembled more to my mother, and my brother resembled to my father. And you see how fate is. My father was buried here and I will die here, and my mother is buried in Israel, and he will die there.

But I visited there three times: in 1975, in 1983 and in 2002. I liked it, it’s a nice country. Jews came from all around the world, who, in my opinion, teamed up and have transformed the country. The southern part is a bit more like a desert, but there is a nice town there, Beersheba, I have visited it. I have been in Qiryat Tiv’on at my colleague’s, Avi Haber, I have been to Qiryat Motzkin, at my colleague’s, Sica Manas, I have been in Rehovot, at my cousin’s Miriam Kruger. I have been in Tel Aviv, I saw two towers made by rich people, Jews from Argentina or Brazil, similar to those which were hit on the 11st September. One of them has 64 floors, the other one 48 floors. There are very nice shops, supermarkets and restaurants on the ground floor.

In my childhood I lived in a house, in a small house on 10 Mirautilor Street. After that I moved from there, because I inherited a house from aunt Sophie right across from the market. After I invested money in that, it was demolished, and they gave us a very small amount of money at that time. 5 years ago with this restitution law I also made an application, because they told me that they would give me the value difference from that time. But I haven’t gotten anything so far. Now my wife and I live in a flat and we live off our pension, we don’t have any other income.

Glossary