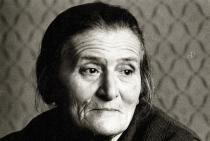

Lilya Finberg

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Tatyana Chayka

My family background

Growing up

During the war

Our return to Kiev

Married life

My grandchildren

I was born on July 9, 1926, in Kiev. Until 1925 my parents lived in the town of Vasilkov, Kiev region. I was named after some relative; unfortunately, I don't remember exactly who she was.

I never saw my relatives - aunts, uncles, grandparents - on my father's line. They did not live in Kiev; they lived somewhere in Crimea, and nobody would ask about them in our family.

My mother's father, Lazar Gokhfield, was the favorite of the whole family. I named my son after him. Grandfather Lazar - his Russian name was Lyonya - died on January 21, 1940. He was a very decent and holy person. I remember his solemn funeral. It was only much later that I realized that it could have turned into trouble and even arrests for some members of our family. Rabbi Ganopolsky led the funeral both in Yiddish and in Russian, so that everyone would understand. A lot of people came. The ceremony was held out in the open; people showed no fear of possible persecution.

Besides my mother, Grandfather Lazar had three sons. He lived with them on Krasnoarmeiska Street, while we lived next to him on Tverskaya Street. His wife, my grandmother Rivah, died in 1937 in Kiev. My cousin was named after her. Grandfather's family and our family had very good relations: Grandmother Rivah looked after all of us. I don't remember Grandfather's profession; as far as I can remember he worked around the house. He was religious in an old way. He did not go to the synagogue every day, but regularly. In his family, they kept Shabbat, while in our family I don't remember keeping Shabbat. My grandparents spoke Yiddish between themselves, and Russian to us. They dressed as ordinary urban citizens.

There were four people in our family: my father, my mother, my elder sister and me. My father's name was David Izrailevich Braginsky. He was killed during the war, approximately in 1942. My mother's name was Roza Lazarevna. My sister, Bronislava, was four years older than me. We called her Bebah. In 1940 she graduated from high school with honors and entered the Mechanics and Mathematics Department of the Kiev University without exams. At the time, it was a grand event.

My father was an engineer. In 1937, he was a master of a workshop of some factory in Podol that made plastic items. I don't know what institute he had graduated from. My mother graduated from the Knekker college after the Revolution. I don't remember where she worked before the war. My mother was a real lady, and my father was a stately man. They were a beautiful couple. At home, we spoke Russian; Mother and Father would speak Yiddish when they wanted my sister and I to remain ignorant of what they were saying. Neither my sister nor I wanted to learn Yiddish - at the time, it was out of fashion.

I don't remember going to the synagogue before the war; it was not accepted among the urban Jewish youth. Among the Soviet youth, to which my sister and I belonged, any manifestation of religion, in any form, was considered a sign of degradation, illiteracy and shame. Only after the war, when I got married, my mother-in-law and I went regularly to the synagogue.

My sister and I went to the Ukrainian school and celebrated Soviet holidays: May 1, the October Revolution, and our favorite, New Year; we all decorated our New Year tree with handmade toys. Family holidays were not encouraged very much. Instead, revolutionary, public holidays were celebrated with a lot of joy. The Day of the Great October Revolution and May 1 were always celebrated with a military parade and demonstrations with red flags, portraits of Soviet leaders, and Pioneer songs. We loved all of that very much. I don't remember celebrating Jewish holidays before the war.

My first friends outside the house were neighbors - a friendly company of children of the same age who were not divided according to nationalities. We had a yard, and on warm summer nights we would take folding beds and spend nights together under the open sky. I went to school when I was 7. Our class was friendly; everybody became Pioneers. My Jewishness never touched my childhood consciousness. The first time I was called a "kike" was only after the war. Before the war, my sister was the best student of Ukrainian school Number 32, which we both attended.

I only learned of the arrests of 1937 by hearsay - praise God, there were none in my environment, school. A family legend is linked with an arrest: Before I was born, when our family lived in Vasilkov, we had a piano, on which young Bebah played "The Cry of Israel," which created a deep emotional response in the Jewish community. When commissars came to our house to look for gold, the young child told them where Grandfather had hidden it. Grandfather Lazar and his two sons were immediately arrested. They were released two months later - since nobody ever had gold in our family. And in 1937 we were Pioneers and adored Lenin and Stalin. Our favorite prank was to run into the Catholic Cathedral wearing our red Pioneer ties, shouting, and extinguishing all the candles. When we grew up a little bit, right before the war, we began to keep up a correspondence with boys from the naval academy that was across from our school building. Through windows we would set up dates. At the age of 14, we had little interest in politics, and there were no Communists at home.

I never felt that the war was coming close. We had a radio at home - a big black plate on the wall between windows; it would constantly broadcast something, but I don't remember paying any attention to it. I learned about the fascists and their atrocities only during the war. Before the war, you could hear Yiddish anywhere in the street, in the market, in streetcars - however, only from those who were older than 20, who seemed way too old to us. My parents went to the Jewish theater, where Yiddish was spoken on the stage. My sister, our friends and I would go to the "Echo" cinema to watch heroic Soviet films - the same ones, many, many times.

War broke out unexpectedly. I remember a crowd of people outside the Vladimirsky market. Everybody was listening to Molotov's address to the nation, from big black speakers that were hanging on posts. Women were crying. Men were called up to the army. Our family was getting reading to evacuate, while my father was called up to the army. Bebah with our aunt - my mother's cousin - and her family were the first to evacuate. Her husband, an officer, and she, a Komsomol member, said it is too dangerous to stay and wait for the Germans. Nobody ever mentioned the danger for the Jews to stay! We left on July 16, in carts. There was a lot of bombing across the Dneiper, in Darnitsa. A 6-year-old girl was killed in front of my own eyes - I can still see it vividly. I was 15. I was riding with my mother and her elder brother, Itsik. By horse, we reached Kremenchug, where we were put into railway cars and taken to the Urals. The journey took two months. It was very crowded; we did not always have something to eat; the good thing was that we still had some money. Uncle Itsik gave each of us small purses with money in case we got lost. We tied them around our bellies.

In September we reached Udmurtiya, west of the Urals. Our family was split up. My mother and uncle were sent to one section, I was sent to another section, which was 18 kilometers away. From the time I was 15, until my mother's death after the war, I never had a chance to live with her again. We were settled in barracks that had rooms for men and women, about 10 persons in each. I worked in the office, while Soviet prisoners and German prisoners of war worked in peat production. This was the first time I saw them; I remember they would fall down, dead, in 40-degree frost, wearing hardly any clothes. At night they were taken outside the village and thrown into a special pit for the dead. They all were not older than 25. We had no particular hatred toward them then.

In the office I worked with papers, wearing special winter boots and a padded jacket; ink would freeze in the ink pot. I worked for 10 hours a day. It was a little warmer in the dorms. I remember nothing but work there. I remember getting sick with jaundice. I also remember planting potatoes and turnips to eat. Our salaries were tiny, not enough to buy food. On the only day off - Sunday - I went to see my mother, walking 18 kilometers through wild woods.

There were practically no military personnel in our territory - only camp guards and guards for the German prisoners. Somebody would always escape from the camp and get caught. I remember practically nobody from the local population. I only remember that people who were evacuated lived there.

We knew little about the course of the war, and had no idea what the Germans did to the Jews. We did not get a single letter from my father from the front. We learned about his death, somewhere in Austria, only after the war.

In fall of 1943, after Kiev was liberated, we returned home. It was not so simple; we had to have a special invitation. I remember Kreschatik Street being leveled - there was only a narrow board, on which two men could hardly walk together; the rest was broken glass and bricks. Without permission, somebody occupied our two-room pre-war flat in Tverskaya Street. The former owner of that house, a Ukrainian - Petro - let us stay in his flat. Six months later, my mother managed to get our home back through the court, which was a unique case at the time.

I was 17, and before the war I finished only eight grades. During the evacuation I had no chance to study, and after evacuation I could not study - I had to earn my living. My mother lived with Bebah, who was very ill and needed permanent care. I went to work at a trust company; then, while I was working, I studied and got a bookkeeper's diploma. For the rest of my life until my retirement, I worked as a bookkeeper in various establishments. I worked for more than 40 years.

Gradually, all of my mother's relatives returned to Kiev from evacuation. Fortunately, none of them suffered. In general, people did not like talking about the tragedy of the Jewish people in the first decade after the war. Words like "Babi Yar" could only be whispered. Officials were planning to build a stadium there. Citizens hated the Germans - I remember how they were hanged on Kreschatik Street in the beginning of 1944, but their "love" for the Jews was not great, either. I can't comprehend this - after the tragedy in Babi Yar, the attitude toward Jews in Kiev was much worse than before it. This became especially obvious during the period of the "Doctors' Trial." It seemed that traditional anti-Semitism was supported by anti-Semitism "from above" - people simply would not go to Jewish doctors who worked in Kiev. However, it was not always the case. My sister, Bebah, who was an ophthalmologist by that time, and her husband, who was a surgeon, worked successfully in the village of Irpen outside Kiev. I also did not feel this attitude personally. At work, we had a very friendly company of people who did not judge anyone by their nationality. Starting with Victory Day, we celebrated every holiday together: although we lived in poverty, the atmosphere was still very friendly.

On August 3, 1947, when I was 21, I got married. My husband, Kushel Pinkhosovich Finberg, was our neighbor. His mother liked me, and then introduced us to each other. He was older than me and worked as a master at a factory, where he certainly could not be called Kushel among all the goyim; there he was Kolya: Nikolay Pavlovich.

Unlike the pre-war times, we tried to change our names into Russian ones. Gradually, these Russian names erased our real names even at home - they have now returned to us in our grand- and great-grandchildren. We had no wedding ceremony - we were too poor. We only had an official registration. We lived in one of the two 10-meter rooms with no doors. Another room was occupied by Aunt Ida and her daughter. Our furniture consisted of a table, a wardrobe and a bed. When our son Lyonya was born in 1948, we ordered a handmade little sofa for him. We had neither a cradle or a stroller then; until he began to walk, we had to carry him. I had to stop working for several years; I had to raise my son. Putting him into a kindergarten was a real problem. I sewed all his clothes, even slippers and shoes. Praise God, the famine of 1947-48 did not touch us directly.

With my marriage, my life began to fill with Jewish traditions and Jewish religion again. Thanks to my mother-in-law, keeping the main rituals and attending synagogue became a normal thing for us. My childhood and adolescence during the war were spent in a Jewish environment, but it was very assimilated. My mentality was Soviet, rather than Jewish, with its two main characteristics: first, atheism; second, internationalism. There was simply no place for Jewish traditions or faith. We all believed in Communism and feared nothing. The war and the Holocaust radically changed my mind. I had a feeling of irreplaceable loss and I was drawn to my roots, to God; I began to fear to break His commandments. Everything my mother-in- law would say or do became understandable and necessary for me.

When Lyonya went to the second grade, I returned to my old job. Since he was 8, my son grew up almost independently. Independence, diligence and firmness of purpose are still his main characteristics. After graduating from high school and technical school, Lyonya tried to enter the Kiev Polytechnic Institute four times. Finally, he entered, and he graduated. Even now, my son is the joy and the pride of my life.

Since the 1970s, people began to leave. None of my relatives left at that time, but at work - I worked at a hospital then - emigration became a regular thing. People left for Israel. It was hard for them; they had a lot of obstacles from the Communist Party leadership and other authorities. Special meetings were held that accused and humiliated the emigrating Communists. Accusations coming from the Jews were of the highest value. At work, we also had such meetings, but no one dared to ask me of such a "service." On the contrary, the director of our hospital informally told emigrants that they were doing the right thing. Our family unambiguously decided on this issue. We did not want to leave. I was, and still am, afraid of the paramilitary situation in Israel. The United States was too far and unrealistic, and we could not even think of moving to Germany. The feeling and comprehension of the Holocaust became a firm part of our lives then.

In 1983, I lost my husband. It was a terrible thing for me, and I remained on this earth with only one-half of myself. However, my son's family had grown by that time. My son and his wife, Lena, gave me two grandchildren - Marina and Arseniy. Now, all of them are taking care of me, while I'm doing my best to help them at home.

In the 1990s, the formation of independent Ukraine and transition from Socialism, to which I had been accustomed since my childhood, did not affect me too much. By that time, I had long since retired. However, my pension was inadequate, considering the 40 years I worked. But I live with my children, while lonely pensioners immediately turned absolutely poor.

At the same time, in the past eight to 10 years, Jewish life entered our house with the confident walk of my granddaughter, Marina. I can't say that our whole family accepted her way of life, up to keeping kashrut. All of us, from me to the youngest Arsen, are free in our choices. And our different choices did not cause us to quarrel. We care for each other very much.

Everything else I see around me brings me both joy and fear. It is nice to see the blooming of the Jewish life in Ukraine. I'm proud that my son plays a great role in this - he is an organizer and the director of the Kiev- based Jewish Studies Institute. It is frightening to see that there still is anti-Semitism, only in a different form. I hope for the common sense and kind hearts of good people, who prevailed in my life.

Over the past 15 years, I do my best to go to Babi Yar every year. It has finally become a civilized place of honoring our tragedy. Flowers at the Menorah memorial at Babi Yar and Kaddish have become part and parcel of my life today.

I would like to live long enough to see the weddings of my grandchildren and the birth of my great-grandchildren. I hope that wherever they live, they would be happy. I am very much afraid of war. I have a great hope for peace.