Laszlo Nussbaum

Kolozsvar

Romania

Interviewer: Molnar Ildiko

Date of interview: December 2001

My grandfather on my father's side, Heinrich Nussbaum, came from Transylvania 1, from a community called Zsombor, I think; this is somewhere between Kolozsvar [in Romanian: Cluj Napoca] and Zilah [in Romanian: Zalau]. This is the only thing I know, except that he was born in 1864 and lived in Budapest. He had a wife, called Zseni Nussbaum [nee Seelig], with whom he had four children, and all four were boys: Laszlo, born in 1898, my father Jeno, born in 1899, Jozsef, born in 1900, and Sandor, born in 1902. He was an active military officer, but I don't know what rank he had. Well then, what active military officer goes to church, and especially a Jewish officer to the synagogue? He was completely atheistic. As a soldier, he was transferred to Znaim. This is an area in the North, and they went there with the four children. But he would have liked to have a daughter anyhow, and my grandmother died in childbirth together with the child in 1908, who, by the way, was a boy. So the father was left there with the four children, and then World War I started.

Family background

Growing up

During the war

Post war

Glossary

My grandfather wanted to get married again, but had a condition: he wanted a woman who already had children. He was at the age when he didn't want a new child because he had 17-20-year-old children. He met a widow in Vienna who had lived all her life with her husband in America. Her name was Paula, she was a Jewish woman of Austrian origin, and she spoke German. She became a widow there in America, and then went back to Austria with her child. My grandfather met her and married her in 1914, presumably in Vienna. There were five boys in the house, and they played together.

In the first year of their marriage, it happened that her son fell down and died of blood poisoning. One can imagine how she must have felt: there were those five children playing, one of them was hers and that is the one that dies. She was completely lethargic for almost a year, and what is very strange is that she changed from one day to another. She accepted the four children, became their mother.

My father comes from this completely assimilated, Austro-Hungarian Jewish family, which means that as a matter of fact, he had no knowledge of religion. None at all, which includes the fact that he couldn't pray and he didn't know the Hebrew letters. He knew he was a Jew, and that's all. The typical assimilated Jew: it often happened that they wanted to be more Hungarian than the Hungarians. He was also a bit of an opportunist and adapted to fit the situation. He wasn't unusual in this way; it was a general characteristic, an acknowledgement, gratitude for the permitted emancipation.

They must have had a rather good financial situation; but exaggerated patriotism, that's something they definitely had. After the few years of the war, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy grew poor; it issued bonds 2, and those who bought them received a given percent of interest, if, of course, the state were victorious at the end of the war. I'm quite sure that my grandfather bought a great deal of war bonds in order to further victory for the Austro-Hungarian army, which lost the war in the end. Then he was discharged. He could not be a soldier after the war was lost, and he remained with his children, and with his money.

My grandfather decided to go back to Transylvania, where he had relatives, so he bought a house in Torda [in Romanian: Turda]. They came to Torda, and they lived very well there. He was quite a rich man; his fortune remained even after the war. As far as I know he wasn't engaged in anything. They were just the two of them, Paula and my grandfather - they didn't have a house large enough to need a permanent servant. Later my father and mother lived close to them. My father was there visiting them every day. I don't think they organized meetings because there was a problem: Auntie Paula knew only German, so she could only have a circle of friends who spoke German. But only a few people in Torda spoke German. She also spoke German with my father. She never learned Hungarian or Romanian.

And here comes the spicy part of the story: In 1918, when they still lived in Budapest and my grandfather wasn't so old, he decided: I have four children and I'd like them all to go to university. But his requirement was that they all go to different places, though he wouldn't pick where. He sent the first child, Laszlo, to Paris, to the Sorbonne University. With the second child his restriction was that he couldn't go to France. He could go anywhere, except to France, and he couldn't study philosophy like the first one had. This one, Jeno, my father, went to Italy, to Florence, and he studied mathematics; he got a diploma and a doctorate. Then the third child could go anywhere but these two countries and he could not choose these two professions. So the third one, Jozsef, went to Berlin and became a doctor. The fourth child, Sandor, went to a different country and chose a different profession as well, commerce in Prague, to be precise. Grandfather used to call it: 'Spreading my germs all over Europe, because I had enough of this war, but I want children everywhere.'

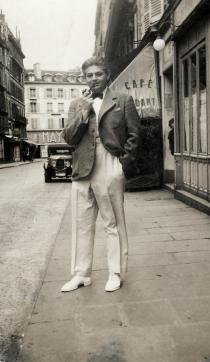

The elder brother in Paris lived a bohemian life. He lectured at the Sorbonne and he had lot of money. For example he went to Nice for the summer holidays and he spent all his money there. It happened that my father didn't receive any letters from him for a long time, and then a letter came from Zanzibar or somewhere that he didn't have funds to get back to Paris, and he wanted them to send money.

I remember that my father received a letter in 1937 in which he was urged to go to Paris immediately because something bad had happened to Laci - I was named after him by the way. I only found out the whole story later. My father went to Paris, he went up to his apartment, and he rang the bell. 'Jeno!' cried Laci, 'What are you doing here?' My father didn't know what to say because he was told that something bad had happened to him. 'Is something wrong?' he asked. 'No,' came the reply. He didn't understand why he had been summoned by telegram. They went to have lunch somewhere, and there it came out that he had pawned everything, even his clothes. So he had a completely bohemian life.

Laci never got married. But he had partners until the end of his life; in fact, his last one was scarcely a year or two older than my wife. I still keep in touch with her. He had no Jewish girlfriends, but he didn't change his Jewish religion. He is buried in the Jewish part of a cemetery in Paris; his last live-in girlfriend buried him there in 1967. On 1st November [All Saints' Day], she takes flowers to his grave, though it's not a tradition for Jews.

The third brother was a doctor until 1937 in Germany, but in 1937 the situation was unbearable. He stayed two more years, until 1939, and then he went to London. Refugees from all over the world were gathering in London. He couldn't be a doctor there, but he had a brilliant idea: one couldn't go to America just like that, so he had one chance: to get married to somebody. He just took out the phonebook and called somebody up - I only found this out later. He called mostly women with nice names and he told them his intentions frankly. In the end somebody went along with it. He fled with an American woman to New Jersey, near New York. This was about 1940-41. He couldn't be a doctor yet, because he would have needed to have his diploma acknowledged.

In the meantime, America entered the war in 1942. He attested immediately as a volunteer - as I found out later - because he would have been drafted anyway, but he needed to be a volunteer in order to obtain American citizenship faster. There he could be a doctor, in the war his diploma was acknowledged and he went to Germany, to the German front. He told me the following: 'If I had seen an SS soldier three years before, I would have done a number two in my pants.' He never said in which part of Germany he was, but as a major he had an area of responsibility in which he was the commanding officer, from the medical angle.

There were different commando units to catch the SS officers and put them into a concentration camp, which was called a jail. In his district there was such a jail for SS officers. From a distance, when they saw that an American officer came on duty, they jumped to attention and shouted: 'Achtung!', although a couple of years before he had been trembling because of one little SS officer. He returned to America after the war and worked as a doctor until he died. He lived with his wife; they had no children. He died in San Antonio in 1981.

Sandor, the youngest brother, was born in 1902. He was somewhat younger than the others, but as for his stature he was the only one who turned out to be small. He stayed a longer time in Czechoslovakia. All I know about him is that he held some leading post at a textile factory at Kelenfold, near Budapest, but he lived in Budapest. He must have been well-off, because he didn't want to get married. He felt fine by himself. My father met him every year, almost compulsorily.

In 1942 they called Sandor from Budapest into forced labor service. Supposedly they took him to Ukraine, to some labor camp. They took him away, and he never came back. He wasn't married; he left nothing behind him. After the war they delivered the documents back; the Hungarian Resistance and Antifascist Alliance gave us a paper in which they only said of my uncle Sandor Nussbaum, that he was drafted into the forced labor service on 2nd October 1946 in Nagybanya, from where they took him to Ukraine, where he died as a consequence of the cruelty of the Hungarian members of the skeleton staff. They ascertained all this after the testimonies and the list of Yad Vashem 3.

It's true for all the brothers that they didn't change their fate, none of them became Christian, but none of them was religious. They didn't practice anything religious. They didn't go to synagogue, didn't pray. I think they were circumcised. Let's not forget that at the end of the 1800s, though the assimilation had already started, the tradition was still very strong.

The four brothers met at their father's funeral. This was the only event at which all four met up. They had different jobs in different countries; they couldn't arrange their holidays that way. It wasn't rare that three of them met each other, and two of them saw each other quite often: my father went to Paris or the one in Paris went to Prague, they often were on the move, but all four met only at their father's funeral in 1932. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Torda.

My father studied in Italy, and when he came home to Torda to pay a visit he met my mother, Ilona Weinberger. It was quite rare in those times for girls to graduate after middle school. My mother graduated. I don't know under what circumstances they met, but they got married. The only one who didn't find a foreign wife among the siblings was my father. All the other children remained in the country where they had studied. My father went back to Italy for a couple of years to finish his doctor's degree. Then he came back and they lived together with her family in Torda until 1940.

The house we lived in was in the very middle of Torda's main square. After World War II, there was a Soviet monument exactly opposite our house. It has been demolished by now; they have built housing blocks there. It was a one-story house. It had an arched entrance in the middle, where the drays and lorries could enter, but there were two stones, one on either side of the entrance, to prevent the walls from being damaged. There was a shop on each side of the entrance. I think they sold hats and fashionable items in one of them, and in the other also clothes, perhaps. The shops were not my grandfather's, but he rented out the space.

The apartment itself was on the upper floor. This was the home of the grandparents on the mother's side and their children, except my mother, who was married and lived in that house as well, but in a different building, in the yard, with a private entrance. At the back of the yard there was a huge building consisting of one hall. A textile factory operated there, but it wasn't my grandfather's, he rented out the space. At one time there was a kindergarten, too. There was another street parallel to the main square, a few hundred meters away, and the other entrance of the house looked on to the other street. There was a coach-house where we used to play with slingshots and arrows.

There were fruit-trees and a big yard where my brother and I could play. Sandor, born in 1930, was two years younger than I. There were many children that used to come to our house; we played boy-games, like cops and robbers. There were shed buildings on which we climbed and then jumped down. There was a game called clumsy: a rhombus-shaped piece of wood stood askew, and one hit it with a stick, it flew away, and we measured the distance with paces. In another one, we drew a circle in which you had to strike off a little stick with a bigger stick at a certain distance. And another child, from that distance, if he managed to catch it, had to throw it into the circle. If he couldn't, you won. But the farther you threw, the less probable it was that he would hit that circle. We had battles like that there.

In the yard my grandfather on the mother's side had a brewery as well, but without a shop or counter. It can be imagined as 50-60 square meters in total; this so-called factory was a 'bottling plant.' There were workers, but only a few; there must have been two or three of them. This was a place on the ground floor, I can't remember the manufacturing, but playing in the yard and peeping in the entrance-hall one could rather see the corking part. According to the habits of the time, there were few lorries but many drays came in instead in order to carry the goods away. They didn't work on Sabbath. I know that my grandfather never worked on Sabbath, he was very religious.

I know only one thing about the childhood of Moric Weinberger my grandfather on the mother's side: I think that Egerbegy is near Torda, and his parents lived in that village. At the end of the 1800s Gypsies attacked them in their house, they robbed them and killed them. This is all I know. They found them dead, murdered. The children were bigger, 19 or 20 years old, and only the two old people were at home. I don't know anything else. The children already lived in Torda at that time.

My grandfather was a very religious man, an Orthodox Jew 4. He was European, wearing civilian clothes, and had neither beard nor payes. I suppose that as a child he used to walk around like the other children, with payes and all, but later he didn't any more, but he was very religious anyway. The period before the emancipation in 1800 was completely different to the one after 1923 5, during the permitted emancipation.

His religiousness had many facets. One of them was that he had a high position in the Jewish community. He wasn't president, but I know that he was the manager of the administration of funerals and weddings. One should consider this not only from a religious point of view, but from an administrative one as well; he was responsible for the payments. He had a thorough grounding in it, and he went to the yeshivah, I think in Pozsony [today: Bratislava, Slovakia]. This was within the frame of the Austro- Hungarian monarchy. The most important manifestation of religiousness is one's prayers. They put tefillin on their arms and they say a given prayer. My grandfather used to have tefillin like that and every day in the synagogue or at home when he couldn't go there, every morning - in the evening he didn't have to - he prayed with tefillin. In the synagogue he sat near the rabbi, opposite the congregation.

Besides religiousness, tradition had to be preserved to the very end. The Friday evening ceremony began with washing, and of course my grandfather went to the mikveh and to synagogue. There was a mikveh in Torda, too, but I never went there. This was nothing else but plunging in only to keep the tradition.

There was a casino, too, in the center of Torda, which wasn't far from my grandparent's house. In 1940 the casino still existed; it was mostly a very serious forum. It was a meeting place that was separated from those of gentiles. It had many sides: one was entertainment. But one shouldn't picture it like nowadays' roulette, they didn't play for money. In the parlor games - they played chess, rummy, cards - one could not loose or win, but only have fun. But at the same time it was a political meeting place as well. It was a very serious center of culture and debate, the essence of which was whether somebody was Zionist or not, because the groups were built according to this.

The casino gave space to any Zionist organization. I remember, when I was a child, there were a few Zionist organizations: Hanoar Hatzioni 6, Shomer Hatzair 7 - leftist, then there was the Betar 8, a rightist extremist organization. As far as I know, my father didn't participate in any Zionist organization, he had cosmopolitan feelings. It was a big hall, this casino; they used the place for different literary evenings, when somebody would read aloud. Or sometimes there were some guests: Zionist leaders, writers, and journalists - mainly from Kolozsvar - who held rather serious lectures. It also happened that lectures were given by children, about the story of Esther, for example.

In those times dozens of Jewish publications were edited both in Hungarian and Romanian. Actually these were not religious books but ones of a political, Zionist character. There was a printing works in Lugoj; they brought Hungarian publications from there, but one could get them from other different printing works, too, or they sent such things to the casino. In the casino as well as at home, there were moneyboxes called Keren Kayemet 9, we also had one at home on the wall - I remember there was a map of Palestine on it - because it was a tendency to buy the lands in Palestine. They brought them to everybody and left them there, and the members of the families put money in them, which was emptied from time to time. The children put coins in as well.

There was a Jewish organization of Zionist character, the WIZO 10. In the 1930s it was not customary for women to work. As housewives they always had time and energy to meet during the day. Those who were more active, participated in this activity. And they were probably more educated women. My mother participated in it as well, I remember that we asked, 'Where is mom?' 'Well, she went to WIZO.' That's all I knew. The women organized meetings, but it didn't mean that men couldn't come. They organized such meetings where there were kind of buffet meals, too, but rather liqueurs, brandy and cookies, which they crunched during the evening.

In Torda the custom was that they made chulent on Friday and put it in a big pot or clay vessel, moreover they tied it with a wire, so as it could not break up. Chulent is one of the traditional foods. It has nothing to do with religion, but it developed over the centuries together with the other traditions. Actually it is beans, which are eaten on Sabbath, and because it's not allowed to cook on Saturdays, it is already prepared on Friday. My parents bought a goose, had its breast pickled while it was stretched. They put it in the smoking chamber and it became smoked goose-meat, just like ham. They put it in this dish of beans, which is a simple vegetable dish, and this meat gave it a good taste. They didn't put fat in it, because the fat melts out from the fatty breast of the goose. And what remains is delicious, softened and very well-smoked meat.

On Friday afternoon, they took the prepared chulent to the cooking place, where there was a bigger stove or oven. It was cooked in a moderate oven for ten-and-something hours and was taken out at noon on Saturday. We were wealthy and the maidservant brought it for us. They wouldn't have entrusted to me, the carrying of the eight-kilogram goose, wrapped in wire netting, in an earthen vessel which was held by the lug. I remember a great scandal as well. The clay pots were all very similar and somebody put a hand of pork in theirs, and the hand of pork ended up with Rabbi Adler of Torda, and there was a great scandal because of it, and from that time on they demanded that the pots should be sealed. I remember that we laughed because they had to be so thoroughly closed.

On Friday evenings, the preparations of the family at home were wonderful; I can't imagine anything more beautiful. The atmosphere of Sabbath was in the air. The clean house, the smell of challah, its odor could still be smelled. The candle was still unlit, but the two big candlesticks were there on the table and the match, which would be struck by the woman, was nearby. There was an atmosphere, which was only present on Friday evenings. Only my grandfather went to the synagogue, my father couldn't be dragged there, and I don't know if any women in my family went either. Women went only on high holidays; my mother and father both went on such occasions, but not every day.

On Friday evening, my grandfather came home from the synagogue, and the dinner was ready. The typical Jewish cuisine: fish in aspic, made in a special Jewish way. It is made mainly with carp; as far as I know, they cook it without gelatin, let it cool down, and this is how it turns into a meat jelly. The braided challah with poppy-seeds on it, which of course, is picked up and coated in salt by the head of the family. There were no sweets. My grandfather spent the whole morning in the synagogue on Sabbath; then there was the typical lunch of Sabbath midday. Mostly we had chulent. There was also chicken or goose meat-soup. I remember even today, that the soups had a hearty yellow color because of the goose or hen fat; I haven't eaten such yellow soup since then. It wasn't possible to be late for lunch, or to be busy. The family was together.

I don't remember my grandmother. She died in 1932 and my grandfather never got married again. He lived with his bachelor son [Jeno], and with his as yet unmarried daughter [Zita]. His other daughter was my mother. That's how it was until 1940. I have quite a lot of memories from this period. There was a huge fenced veranda, where we used to eat in summer; at a big table with ten people, not including guests. There was a dining room as well, which you could walk through, then came the so-called salon with a piano etc. and with furniture typical of the beginning of the century. There were fringed draperies on the walls, little armchairs. Sometimes there were organized salon parties, musical evenings, because my mother's sister finished a conservatory. There were two bedrooms in the house. My grandfather had a double bed, in which he slept alone. My parents lived in a completely different part of the house, in a three-roomed apartment.

If I remember correctly, my mother 'managed' the house, together with the larger, common household. She also cooked, but there were two gentile servants as well. 'Managing' actually meant the following two things: she arranged the menu and she took care to make sure that the food was really kosher. Tradition was important for my grandfather. My mother took decisions about kosher dishes and the education of the children. I can't say much about my mother's religious feelings, but she always followed the traditions. It was no problem that the meal was made by gentiles. There were no conflicts. My father actually went to a restaurant if he didn't want to eat ritual Jewish food.

We observed Jewish holidays. We carried through that terribly boring ritual, seder, at Pesach. But I have no particular memories about that; just the usual things went on. On the eve of seder the dinner of course, wasn't only a dinner, it took on a special religious form. We had to say different prayers before dinner. When Grandfather looked away, I took the afikoman because my parents encouraged me: 'Now, take it quickly, your grandfather is not looking.' 'Where is it? Where is it?' he asks. And the little child laughs. 'Do you have it?' he asks. 'Yes, I do.' 'Give it to me,' he says, 'I won't,' I replied. 'Then what should I give you for it?' Well, this was a playful thing.

It was not a singing holiday but a long, story-like thing. They said the whole thing in Hebrew; meanwhile my mother told me what it was all about. Maybe she read it. Later, when I was older, I started to read this as well. Apart from that, I didn't understand a word. I just looked at the pictures in an illustrated Haggadah, which bears the detailed moments of the ritual of the Eve of Seder with fabled explanations.

There was a part of the ritual when my grandfather held a glass in his hand and spilled the liquid out of it. In the meantime he explained how God punished the people of Egypt: blood, frogs, hail, locusts etc. and he spilled a little out at each one. The other thing I have in mind: they filled a glass with wine and put it on the corner of the table. No one touched it and the door had to be slightly ajar because Prophet Elijah was to come in, and the glass belonged to him and he was to drink it in praise of God. As a child I always asked when the prophet intended to drink it. The glass was there until the end of dinner.

The extended family wasn't big. Our family was big; we were seven without guests. There weren't very many more of us during holidays than otherwise. [Editor's note: The interviewee's father moved to his wife's family; of course, as a young couple, they lived in a separate building of the house.] My mother was the oldest child in the family, and she had one brother and one sister: Jeno and Zita. Jeno, born in 1908, graduated in law in Chernovitz, and he became a lawyer in Torda; he worked until 1940. After 1944 he worked again, in 1950 he moved to Kolozsvar, he died there before the age of 60. He was a bachelor. He was very religious; he inherited the religiousness of his father, which means that the tradition remained in his childhood, which it didn't in my case.

Zita, born in 1918, graduated in law, she was a lawyer as well, and she had a doctorate in law. She got married to an illegal communist and went to Kolozsvar. Her husband was a university professor, he taught economics, and finally they left for Israel after they retired. The brother, Jeno, was almost an everyday guest in Zita's house and he ate there every day. He was a family member there but he didn't use his sister financially. He considered the children of his sister his own. The husband was very busy, so he looked after the children more than their father did. In religious families, women are the ones who carry on the tradition, but religious life is mostly carried on by men, and he was surely religious. He went to synagogue, and prayed. It was he who impressed the religious spirit on the family beyond tradition. He was there with them until the end, until he died at the age of 60.

I had two periods of childhood: the first was until I was ten years old, when we were in Torda, and then from eleven to 14 years old in Kolozsvar, starting in 1940. These two were absolutely separate.

When I was ten years old I became a more-or-less thinking child, and actually, it was then that the laws and difficulties in the school began 11. I couldn't go to school any more because enrollment wasn't allowed. My parents didn't explain it to me, but enrollment was no longer permitted. According to the Vienna Decision 12, which had already been decided months before, South Transylvania was separated from North Transylvania. This meant that Torda belonged to Romania, and Kolozsvar to Hungary though the distance between the two towns is just 31 kilometers. We had two or three months to think. Everybody knew about the Vienna Decision, one could move, come and go, but the whole of Transylvania still belonged to Romania. The state moved towards legionarism, fascism.

As an intellectual, my father was on good terms with the prefect. He was warned that he'd better leave that place, Torda, and in fact Romania, because it could happen that the right-wing fascists get into power, and then he or his whole family would be expelled from the country as a Jew of Hungarian citizenship. My father never became a Romanian citizen, and he had a lot of problems because of that.

There was quite a lot of interest in the Ford car in Romania around the 1920s-1930s. That was an institutional, well-known car. They needed a general representative for Ford. My father applied for it. He went to Bucharest and they asked him: qualifications: this and that; knowledge of languages: German, Italian, French, English, all right. Doctorate degree: yes. They asked him: 'Would you accept the post of general agent?' But then they found out that he was not a Romanian citizen. They said: 'The fact that you are a Jew can be accepted, but to have Hungarian citizenship, we can't accept that.' He couldn't arrange Romanian citizenship or he didn't want to, I don't know which, but he prolonged his stay there every year.

Finally my parents decided to move to Kolozsvar so as the family could remain together. When we came to Kolozsvar people could still come and go at that time: Some of the Romanians went to Southern Transylvania, Gyulafehervar, Torda, Szeben, because they reported on the radio that the Hungarians would take over power beginning on 1st September.

Our first apartment in Kolozsvar was on what is today Horea Street. There is a nice-looking multi-storied house built in the 1930s; we lived on the ground floor. On 1st September 1940, Horthy 13 entered from the direction of the railway station, on a white horse. And we sat in the window and watched him. There were people coming in front of him as well as behind him. The crowd stood at the side of the street and applauded and cheered him. He had a very long military escort: the first part was on the main square, while the other part was only at the station.

The conquering of Northern Transylvania wasn't warlike, it happened by surrender. The first thing was that the army came in, took over power, including among other things, control of the town. Colonel Beck was put there, and he occupied the mayoralty until the state made preparations for the new form of state and they appointed somebody as mayor. I didn't feel any changes at that time except for one thing: in a few days everything went Hungarian. In shops we were allowed to speak Hungarian, we could ask for what we wanted in Hungarian. The Romanian I knew was only what I had picked up at school.

Three or four hard years came: anti-Jewish laws, existential problems. The laws came step by step. It began with the law that a Jew wasn't allowed to be official. After a half year, there was another law: that there couldn't be Jews in companies or private enterprises; they couldn't be university teachers, then they couldn't be high-school teachers, then they couldn't work in education at all. After that they kicked the children out of gentile schools. Then a doctor couldn't treat Christians, couldn't work in a hospital, only in Jewish hospitals, couldn't have consulting rooms. Finally they weren't allowed to work even in factories. So gradually they were displaced from the social life.

Between 1940 and 1944, I think, my father had a private trading enterprise, so they bought and sold something, I have no idea what that was. But it didn't run under his name. A very honest and decent man, Istvan Kocka was the 'Strohmann' 14, the cover name, because Jews couldn't have private enterprises. We were on very good terms with his family and we used to visit them at Christmas. I don't think he had children.

Around my father, my religious education decreased considerably because he wasn't religious at all, but the traditional part of it didn't decrease in any way. My mother observed the rules of purity in Kolozsvar, too. She cooked in a kosher way, the meaty and dairy dishes were really separated; and then my father brought home a pork-steak which we had to eat from a different dish, or we ate it from paper, but my mother didn't taste it. I did, of course. Only my mother didn't. She tolerated it, because she didn't have a choice, she either didn't want to or she didn't dare to speak against her husband, but she didn't mix the meals.

The candle was lit, Sabbath was observed, but my father didn't know the prayers. He didn't speak Hebrew, and he couldn't read it either. My mother could, and she prayed, but she knew only the prayers typical for women, for example before lighting the candle, but she couldn't write in Hebrew. My mother specified the bar mitzvah, she insisted that it be observed. I had learned that passage from the Torah, which I was to read in the synagogue. We observed the religious parts, I read the given passage, but we didn't invite anybody home for the feast, we went only to the synagogue, and I didn't have a speech either.

Already in Torda I had to attend the cheder. My grandfather insisted on it. What has remained is that I still can read a few prayers without understanding anything of them. There was a strange approach to teaching in cheder at those times. They taught us to read in a completely unknown language, Old Hebrew, though we didn't understand a word; we just learned the letters and we knew how to read them. I still read my prayers in such a way that I don't understand a word of them. At that time there was another weird habit: for religious Jewish children, in order to understand the Bible, they translated the text to Yiddish. I didn't know Yiddish, they taught me for a while to translate the Hebrew to Yiddish, from one to the other, though I understood neither of them. There are lots of such traditional anomalies.

And then, in 1940, though the anti-Jewish laws were functioning thoroughly, a Jewish high school was opened in Kolozsvar and they enrolled me there. I never thought of any other alternative. Every Jewish child was matriculated there, we all knew that we couldn't attend any other school and if they had stopped that school we wouldn't have had anywhere to go.

This Jewish high school came into being in a very strange way, it has a fairytale-like story, but there is a little truth in it. There was a young teacher who was called Mark Antal 15; he was a very talented mathematician. In the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, during World War I. he was decorated because of his bravery, and relatively few people were awarded that decoration. He was also a teacher at the university and according to the Hungarian seigniorial laws they addressed him as 'milord.' In 1919 he became a leftist and participated in the proclamation of the Hungarian Republic 16. Since he was a Minister of Education he ran away this way to Transylvania and settled here. The story also goes that in 1940 the commandant of the town was General Beck. At that time the administration still hadn't been organized and the army assumed authority. He asked Beck to permit him to establish a school; he referred to his 'honorable friends in Budapest,' who actually didn't exist, for he had run away from there. The authorization was available in a couple of days.

That was, in principle, one of the best high schools. The anti-Jewish laws referred to teachers as well: they were fired from universities and everywhere. When he got the authorization, he could choose between university professors as he saw fit. Lots of my teachers were university professors. It was a problem for example that once Mark Antal came in to inspect, because he was the headmaster, and he was surprised to see that nobody had received any grades. They forgot to question pupils because they held university lectures. I was a child wearing shorts, and the professor would come in: 'Please, Gentlemen.' They weren't accustomed to it, a few months earlier they'd still been teaching at the university. They held quite interesting lectures; we didn't understand everything, but they never questioned their pupils. Later they had to test the whole class in a week. Then they became used to it, for example to homework, lessons.

The teaching staff consisted of a dozen university lecturers from Budapest. From the second year it started to become a high school. The school had a Jewish character as well. They taught Modern Hebrew for six to eight hours, every week. There was a different teacher who taught this. There was a proper textbook; we learned to speak. In a few weeks one could learn to speak rather well. And there was Religion as well. These had no religious character, they taught religion: when and what to pray, the importance of holidays. Actually we discussed the rituals of Jewish holidays. The whole thing had some theosophical/religious philosophy connections, but we didn't learn prayers. The religious character consisted only of the fact that on certain holidays the whole school, in corpora, went to the synagogue. There were quite a lot of us in the school; we would have occupied the whole synagogue, but they held speeches and prayers an hour earlier or later than the actual service time and we participated in these.

In other respects it was like every other school. There was no school uniform at that time, though the wearing of the Bocskai hat was obligatory, for gentiles as well. The Bocskai was a shako-like hat, and on the front it had a triangle made of braid to show that the child was in the first grade, or second etc. those in the fifth grade got a gold braid. On the front, inside the triangle, there was an emblem, the emblem of the school. 'ZS' was the emblem of the Jewish high school. [Editor's note: The Hungarian term for a Jew is zsido, hence the letters ZS.] It was obligatory for every pupil, and you could recognize immediately by this, who was Jewish, and we got given a good hammering. The problem was that if a policeman came along he would look away. I can't remember any occasion when they intervened. It was very dangerous to walk alone. We had to be in groups. We couldn't expect protection from the law.

There was a sports ground in the area which lay approximately within today's Grigorescu - Donat neighborhood; it was called Haggibor. This was a sports association, which had had a lot of serious activity in the 1930s, but I don't know much about it. We went there only to play football at that time. At the beginning of the 1940s it wasn't an active sports club any more; it couldn't have a team. It was a club 'in a coma,' agonizing, because nobody had taken the ground yet.

At that time those areas weren't built up, beginning with the Torokvagas [in Romanian: Taietura Turcului, a place in Kolozsvar] there were no houses, only gardens. I remember that once I was walking with my brother and I saw from a distance that four or five people were coming towards us. My brother was younger, I was about 12-13 years old, and he was 11. I told him: 'Run quickly to the sports ground and ask for help!' I intentionally didn't run away, because they would have caught up with me anyway, but I thought I would hold them up until he ran away. I saved my brother by instinct. They beat me there in such a way that I was in a pool of blood near the planking. They didn't ask anything, just started to beat me and then they left. I had to be carried home. The doctor treated me for days.

That's how the continuous restrictions went on. But we children heard of these laws only through the problems of our parents. Here is a typical example. Because of the high rent, we moved from the house near the train station to the Mikes Kelemen Street [today's Croitorilor], into a three- room apartment, with a kitchen and bathroom. Opposite this apartment, at the rear of the yard there was another smaller one, which was unoccupied. And once a man appeared in our house, and said: 'Look, doctor, I'd like to move into this house.' My father came and showed him the other apartment. Thereupon the man says: 'No, no, we'd like to move here, to the street- facing part.' My father said: 'But we live here.' 'Yes, but we'd like to move in!'

The strange thing is not the fact that the man who said this was named judge of the County Court in Kolozsvar. He wasn't evil, wasn't a bad man. Then we lived together for many years. The strange thing was rather that this situation was typical, the way he came in and said: 'We want to live here!' and it was natural for my father that they should move into our house. [The interviewee's family moved to the other, smaller house.] The situation was natural for both sides: for him it was natural to kick us out, and for my father it was natural that he understood that. All the laws were such that we couldn't ask for help from anybody; we couldn't even go to court.

The latest restrictions: we could go to the market only during given hours. There was the curfew, then the yellow star, which had to be sewn on the clothes. At that time my father told his 13-year-old child: 'Hey, your grandfather had a brother in Pozsony.' One or two months before being confined to the ghetto he called me and my brother and made us learn, parrot-fashion, all our relatives' names, addresses and phone numbers; he did it in such a way that he woke us up at 2 o'clock in the morning to ask us to recite the address of Laci in Paris etc; at 4 o'clock in the morning, for that of Jozsef in New Jersey etc. We had to recall the number and everything exactly.

Many things became naturally to us step by step, because we couldn't defend ourselves. This is the process of thinning out an ethnic group. They trained us through many years to stand the blows. The highest point of this was the confinement to the ghettos. It's very important that the confinement wasn't enforced by Germans but strictly by the Hungarian administration. At that time there were only a few hundred SS soldiers in the whole of Hungary. The administration was unbelievably exact: who lived in which house, who was a Jew and who was not. There were exceptions, for example, if somebody had a Christian wife. It happened that they came in searching only for the Jewish member of the family, and took him away.

The ghetto was actually on the grounds of the brick factory in Kolozsvar. Every brick factory has big depots where they put the bricks. These are many hundreds of meters long, roofed but open on the lower part for the wind to blow through and dry the new bricks. They put us in those parts without walls, in the ghetto of Kolozsvar. Separation was just that we starched out bed-sheets; it couldn't be any more, that was all there was between us.

When they deported us it didn't matter in which area we were, because they took away the group which lay within arm's reach. That's how I got in the first one, together with my parents. They entrained us and the escort for the train was the Hungarian gendarmerie, as far as Kassa [today Kosice, Slovakia]. In Kassa the Germans took over, but they took away everything they could before that. Of course people had concealed items, for example gold teeth, gold fried in bread. I heard the gendarme myself when he said: 'If anybody has any valuables, you'd better give them to me, because if not, the Germans will take them from you anyway. So give them to me, because you're Hungarians after all...!' Of course, he wanted to pocket them. This is tragic-comedy.

We arrived at Auschwitz together. We had to leave our luggage in the wagons, and the first thing was that they separated the men and women. Then my mother was separated from us, and we three were left. This was the last time I saw my mother. I never found out anything about her. The two of us were together with my father for three months. Later I received official papers and found out that he died about two months before the liberation.

I was in Auschwitz for a long time; it was hell. I tried to evade the work transports, because I knew that they would never take my brother to work. He was thirteen years old and of small stature. I was taller, lankier. At Auschwitz I was under the threat of selection, but I was afraid that if I went away, I would leave my brother alone. In Auschwitz the camps consisted of separate parts, which were there side by side lengthways: 'Lagers' [camps] A, B, C, D etc., which stood separated from each other by barbed wire. In the middle there was a road, and there were barracks on both sides. They all looked the same. Near our 'Lager' there was a women's 'Lager,' and somebody cheated us badly, fooled us, saying that he saw our mother there, and he would throw over what we wrote to her on a piece of paper, if we gave him a piece of bread. And he did this many times. He didn't see her at all, he just wanted to steal our bread.

Auschwitz's greatest selection was in October of 1944. That was when Mengele held this largest selection and sent my brother to the gas chamber. [Editor's note: In fall 1944, there were indeed great selections in the concentration camp among the still living captives. However, we can't utterly declare that one of these was the 'largest' selection.] There is a little story about this. When they were selected, taken away and locked in a barracks, they were watched for many days because the crematory was occupied. The watching was actually done by prisoners, but they had to account to the SS soldiers. I knew such a guard by chance, and I asked him if my brother could be released. Finally, when I was just about to leave, he shouted after me: 'Send me someone; a child with a message, and I'll release your brother.' And then I sent someone, a rather naïve child, who indeed went there. He didn't need to be convinced, I just told him 'Please, take this paper' - because I managed to get some paper. When he had almost made it there I jumped on him and pulled him down. [Editor's note: It would have been an exchange; the one who was sent with the pretext of the message would have been taken instead of the interviewee's brother. But the exchange didn't happen.]

I managed to go to that place, where the children were kept, once or twice more, but they didn't let me get close, I just heard some wailing, and crying children. Finally, after three days, they took away the children; and the man I knew gave me a note ripped from a margarine box. There were a few lines written in indelible pencil, blurred by tears: 'Don't worry, they're taking me to a good place. Be careful not to worry Mom, and I wish you to be free and live a happy life.' Something along the lines. I couldn't keep the note, because when they drove me out of the 'Lager' I had to undress completely, and I couldn't even keep it in my mouth.

From there they took me to Germany, they took this child [who wasn't exchanged for the interviewee's brother] somewhere else, and it's interesting that I met this boy at the liberation in Buchenwald 17. I embraced him. He looked at me and said: 'You're crazy! You asked me to do something, and then you jumped on me and pulled me down. And now I don't do anything and you take me in your arms; why are you so glad to see me?' He never understood why I was so glad; I didn't tell him. This left a great impression on me. I wasn't strong enough to send him in instead of my brother. I thought how I would have felt, if I had exchanged him, and at the next selection they had taken my brother anyway. So it was a happy moment for me to see him alive. I gave him a wide berth after that, I didn't see him anymore; he probably went somewhere to the West.

As far as I know, Buchenwald was the only self-liberating 'Lager.' It was one of those camps where there were mostly political prisoners. The internal management was in the hands of the political prisoners. The Germans organized it in such a way that they charged the prisoners with different responsibilities. Along with their function, they got certain advantages, for example in terms of food. The office administration was done by prisoners as well: who had died, who was going with the next transport. They mostly knew [among the ordinary prisoners] that this one was a communist, that one was a leftist.

These big camps were rather transit prisons; if the factories needed manpower, then they took a few hundred people from here to work. They knew which workplaces were better and which were worse. The Germans selected people for different places in vain; they could change the registry sheet as well as the people. I didn't have connections with them, but they must have thought: 'This is a youngster; let's put him in a better place.' They primarily saved those whom they knew were communist, leftist, antifascist, as well as the children. They saved me because I was a child. They transferred me to a place where the work was easier. If they had put me into a quarry, I would not have survived.

When I arrived at this labor camp [called Tröglitz] where they put me, a guy appeared and told me, whispering: 'Tell them you're a lathe operator!' 'But I'm not competent,' I said. He came close to me again and repeated: 'Tell them you're a lathe operator!' And when I got there and they asked me, finally I said I was a lathe operator's apprentice, though I didn't even know what a lathe looked like. They did this because the lathe operators were in a place which they heated in winter somewhat; it wasn't zero degrees but 3 or 4 degrees; the other places were totally unheated. But they didn't heat it for us; it was the working process that demanded the heating.

There was an international underground organization, which was able to obtain a few weapons. The essence of the self-liberation is as follows: we could not know whether the 'Lager' was laid with mines, and whether the Germans would blow it up, and us along with it, at the last minute, and if so, when this might be. The self-liberation was based on surprise: that the Germans were shot from the inside, from the camp. We had to calculate how long we could hold the 'Lager' and above all: the prisoners. There were prisoners who were generals with previous war experience, and they worked out the plan of campaign; how it should be done.

On 11th April, when early in the morning the Germans shouted to go out to 'Appell' [German for 'roll call'], these people came into the room: 'Nobody is going out! You stay here!' The Germans shouted 'Appell!' in vain. If the senior man in the room said to stay there, then everybody would stay. Soon after that, I heard the first shot. They were shooting at the SS soldiers in the watchtower. We resisted from 11am until about half past 1, when the first American tanks rolled in. So they [the inside liberators] had only to calculate how long we could resist until the real liberators, the Americans, came in.

There was no question of leaving the camp and walking around on the front line before the capitulation, which meant that after the liberation we remained in the 'Lager,' of course under different circumstances. They gave us food at the kitchen, and I have to say that the Americans made a quite a big blunder; though I don't believe it was intentional. They gave us fatty soup, I tasted it, and I felt that I mustn't eat it. Then I saw with my own eyes that many people died within a couple of days at the toilet, with cramps.

They [the Americans] kept us in the camp because we could not disperse. There were three categories: those who wanted to go home; a part of the other category were the skeptics, who said they'd go anywhere but back there; another part wanted to go nowhere except to Israel, then Palestine. Those who wanted to go west could go earlier. Young people were actually received into any country. A 16-year-old liberated from the camp could go everywhere from Sweden to America.

A few weeks after the liberation, the KISZ 18 was organized, and it operated for two and a half or three months. The liberated political prisoners lectured, really wisely and skillfully, just right for people aged between 15 and 18 years. What kind of world was waiting for us? The building of the new world, democracy - they organized lectures on such subjects. Where I was, the lectures were held in Hungarian, but it is possible that they were in other languages, too. There were many people in the camp who were captured by the Germans in France; there were very few young people from there. But they deported the young people from Transylvania en masse. The communist organization held lectures separately for the French adults and the children under 18. They held lectures from morning until evening. Those who joined KISZ clustered together, even in their rooms. These communist leaders held Marxist lectures for the young people in the former SS dining room.

The leader of KISZ was a gentleman called Jozsef Klein, who later lived under the name of Mincu Klein in Bucharest, and published many books. Hilel Kohn [sentenced to death in 1942 at the trial of Szamosfalva, where they sentenced the communists. Nazism saved his life because they deported him into a 'Lager' before he could be executed in jail.], was another well- known illegal Transylvanian Jewish leader; then there was Erno Gall 19, Miklos Kallos, dean and professor at the faculty of philosophy, Nandor Gyongyosi, former illegal leader. Many of the leaders remained in Budapest. Those who decided to go west or to Israel, didn't join KISZ. One didn't have to sign anything, but just joined the group, and at the end they gave a paper that said you were a member of the Romanian KISZ in Buchenwald.

I was 16 years old when we were liberated. I became close to a young American soldier, just 18 to 20 years old. As for him, I saw that he felt that he had liberated a child; he probably felt this because he kept on asking what he could do to help; he was the one who got me used to cigarettes, gave me chocolate and all kind of things and asked me whether I would go with him to America or not. But I didn't go. I came back to Romania. I had many reasons. One of them was that the communist organization - which spoke about the building of the new world, that life wouldn't be like that anymore and we would have to make a new life - had a powerful influence on me. The liberation was coming; a new world was coming. They sowed seeds in a soil, which germinated quickly [the youth]. The other reason was that I didn't know what had happened to my family.

Meanwhile time passed by, the war was about to end; it was after May. It came to my mind that there was still a postal service, and I could send a letter by mail. [Editor's note: The interviewee asked his American soldier friend to write to Jozsef, his uncle in America - whose address his father had drummed into him before being confined to the ghetto - to say that he was alive.] And I set off for home. What I'm explaining now came to light subsequently: he did write a letter to America; my uncle's wife received it and wrote immediately to my uncle, the doctor major, her husband, who was by that time, in Germany: 'Your nephew is in Buchenwald.'

He came immediately to Buchenwald, and it came to light that I had left there a few days before. I could have gone home via Vienna or Prague. It was all the same to me: I decided to go via Prague. He went via Vienna; you know, Vienna was divided into three zones - French, American and Russian - and he could only go as far as the American zone. He managed to contact by telegram, another aunt, my paternal grandmother's sister, who lived in Budapest. She magyarized her name from Seelig to Etelka Szasz. She was a spinster. She informed my uncle that I had left Budapest and gone to Kolozsvar that morning or the afternoon before.

It took a month to get home. We came in groups and we didn't have a map. We made a massive detour in Germany, and after a few days we arrived back at the town we had started from. We went by foot, by ship on the Elba and by train. The train was so full that we traveled on the top of it, and it was even derailed.

I came home to Kolozsvar and realized that there was nothing left, everything had disappeared. My aunt and uncle were still in Torda; I was there for two years until I finished high school. Later my aunt got married. I was admitted to Kolozsvar University in 1947. I always liked mathematics. I was admitted to the faculty, and had finished two years of the course, when they convinced me again that for the building of new life there was a need for economists. And I attended both faculties, economics and mathematics. Two years later a new law came into effect: the socialist school reform. The new law forbade me to attend two faculties at the same time; so then they convinced me that I should concentrate on economics, rather than mathematics, because there was a need for new cadres.

In the meantime I went to work for a newspaper called Igazsag 20 as a freelance contributor, and when I finished university they appointed me immediately to the position of assistant professor. I also worked at a weekly, as an editor; it was called Uj Ut 21. From 1950 I had two jobs: I was an assistant lecturer and editor at the Uj Ut. The Uj Ut stopped in 1953, but I continued writing for the Igazsag.

There was a Jewish gathering after 1945, but not on Jewish principles. It came to life though, namely because the youth, who had returned from the deportation, looked around and couldn't find any relatives - they didn't have a home, they had nothing - and spontaneously began to organize themselves. They gathered in one place and lived together at first. But it didn't come to life because of the Jewish religion and ethnic group, only by chance, because it became an organization in order to organize canteens and housing.

The name of the organization was DZSISZ; this is short for Democratic Jewish Youth Organization. The head office was in today's Peter-Pal villa 22, which used to be Jewish property, but the owners didn't come back, so the organization got it. The lectures were held in these apartments, and we lived there, too, for two years, until the nationalization 23. This organization was a mutual-benefit society, which had developed different branches, like cultural activities, and intellectual self-education. Because, for example, one was a sculptor who immediately made a sculpture about the experiences of the deportation and he unveiled it. Communities, conversations and lectures developed, and the era of those times also contributed to their character, which was more related to socialism and its development. This functioned for a few years, until everybody got to his or her rightful place. It existed until the 1950s, but it was already agonizing then, because I was in the youngest age group, and when we grew up the organization collapsed. We had homes, we went to university hostels, and the older ones got married, so it collapsed by itself.

At the beginning of the 1950s, the following organizations were founded at the same time: the Hungarian Democratic Organization, MADISZ 24 and the Jewish Democratic League. The latter was exactly the opposite of the Jewish community.

At the beginning the Jewish community wanted to organize the people based on religion. But praying is for times of spiritual stability or complete instability, when one prays from deep inside or in despair, and now everybody started to manage their lives, and existential problems came into prominence instead of religious life. The religious community didn't have a Zionist character at first; gradually it took on this character, represented by Moses Rosen 25.

Zionist propaganda was prohibited at that time so it had been organized in a disguised way. This consisted of them holding Talmud Torah classes at the Jewish community so as to know Hebrew, if one went out there. So the Jewish community started the emigration and its preparations step by step from the beginning of the 1950s regardless of whether the government would allow it or not. They taught Hebrew because the Bible was in Hebrew; no one knew the difference between biblical Hebrew and Modern Hebrew [Ivrit]. They didn't talk about 'going to Israel,' but they started to teach Modern Hebrew and Jewish history. The ritual canteen started at that time. This was made by the Jewish community, which became a Zionist organization step by step. Nobody told me to go out there; they just lay the opportunity at my feet: 'All you have to do is to register.' It was then, when the ritual canteen was launched.

At the same time there was the other organization, the ZSDSZ [Jewish Democratic Organization], which represented the anti-Zionist line and wanted to involve the Jewish people in building socialism. The Uj Ut weekly represented their views. At that time most of the young people who came back were anti-Zionists. Not because of the principles of Zionism but because of the communist standpoint: they didn't proclaim that one shouldn't be a Zionist, but that there was no racial differentiation between people. Don't forget we were waiting for the development of the communist idea. It is always different if you look back with today's eyes. Then we were young, we came home from the camps, and here was a new country where we were completely free, where there was no reason to leave. And the communists said that we were the ones who had to build this new structure.

I was a communist, I didn't agree with Zionism. As for me, I never wrote an article against Zionism. Anti-Zionist articles were written mainly by people who went to Palestine but came back or who renounced to it. These were concrete writings, not theoretical articles. The question of Zionism wasn't debated on an intellectual basis but it was about leaving for Palestine, or not. I worked together with the Communist Party, but I didn't write in their papers. I was writing in the Igazsag at that time because that was the only Hungarian daily paper. I agreed with the newspaper that I would remain a freelance contributor and I would write only studies and editorials. There was only one Hungarian and one Romanian paper for 30 years and some periodicals, like the Korunk 26.

I was at the faculty until 1956 as a professor's assistant. That year I was in Budapest by chance and I went to the intellectual council where I knew a teacher, and I looked into how they created the revolution 27. I came home and they told me to write up as an eyewitness of the events, what the Scinteia [The Spark], the paper of the party, had actually already written down. The keynote of the articles was that in Hungary there was a counter- revolution in order to overthrow communism, and that this was carried out by the proletariat mob that robbed the shops. They kept on insisting that I write it until I wrote my own version of the revolution.

What I wrote was not in flat opposition with the voice of the Scinteia, but I didn't write down what I didn't see. I didn't see shops being looted. It's true that they broke shop-windows, but they didn't steal anything. I did not use the words 'counter-revolution.' It had a character of authentic reportage and they didn't like that it wasn't clear in it, that it was a counter-revolution. It didn't come to light from my article that they wanted to upset communism. Finally, they accepted my third rewrite, and it appeared in Kolozsvar in the Igazsag. Then they translated it into Romanian, but it wasn't good enough, not even the third version. And then, well, they didn't fire me exactly, but they transferred me to the university library as an archivist, so that I could not deal with the students. They didn't finish me off, but they didn't let me be a professor, or have direct contact with students.

There were three ideological subjects: Marxism, Economy and Philosophy. The nomenclature of these belonged to the faculty only administratively; the appointments were facilitated by the county party committee. They said that this or that person had to be appointed and then the ministry appointed them. They appointed those whom the Party had chosen. And then the Party said that I was not to teach, so I was just 'passing the time' in the university library for 20 years. I never had any party function, I never had the desire for one, and thereupon I was never mentioned in promotions.

Until 1956 I was undoubtedly with the socialist regime, because I didn't see a better one. It was the only road to take: to resolve the nationality problems, the inequalities of rich and poor. After 1956, there was a period of doubt, which lasted until 1968 when the Russians entered Prague 28. It was the main moment when I came to my senses. Until that time I believed, even after the events in Hungary, that humane socialism was possible - it was such a greater freedom than before the war - and this is more or less what the Kadar-regime 29 wanted to realize. After Prague was overrun, I realized clearly: business doesn't work without a hard dictatorship. The Soviets crushed down every attempt for freedom in the framework of socialism. Something snapped inside me, which slowly parted me from that great and convinced faith in communism.

The problem of my ethnic status manifested itself in a very strange way. In the 1970s the Communist Party introduced official orders, and these grew stronger as in the case of the anti-Jewish laws; they introduced the idea that ethnic status was important in the occupation of different positions; so for example, a university dean could only be of Romanian nationality. I didn't mind this law, but it affected me very much.

I had been working at the university library for a long time before they appointed a Romanian person, with whom I was on informal, friendly terms, as manager. He became the manager though he knew nothing about the library. He made me play, without ill-will, the role of the home Jew. He would call me in asking, 'What should I do in this situation?' He would discuss it with me, and then he would tell the conclusion to the departmental manager, as if it had been his idea. When my departmental manager died he called me: 'Whom should we appoint as a manager at the documentation department?' By coincidence, the newly-chosen man also died after a few years. Then he said again: 'Hey, who should we appoint, because we obviously can't appoint you.' The situation affected me profoundly, because I had to hear: 'I can discuss it with you, but you know I can't propose you. There can't be a manager of a different nationality.'

As a simple librarian I wrote for the newspaper a lot. I had time; in the library I read what I wanted, and I wrote lots of articles. I had to check each item - I had many documents - and after I checked them I wrote about them. There were two of us in the whole library whom they named 'alte nationalitati' [other nationalities]. There were no others except 'maghiari si alte nationalitati' [Hungarians and other nationalities] regardless of whether they were Serbs, Slovaks or Jews.

[Laszlo met his wife, Silvia Brull after returning from deportation. His wife's family hadn't been deported, because they lived in Torda, which belonged to Romania. Silvia was born in Torda in 1929.] I attended the same elementary school as my wife, in Torda, before the war, but I didn't remember her. I left Torda very early, at the age of about ten, and I went back in 1944. Only a few months separated me from the concentration camp and I needed only one thing: great-great silence. I was a young boy, 16 years old and I started to court a Jewish girl, but she could have been Turkish or Tartar, I didn't care. The whole courtship consisted of me going to her in the early afternoon and listening to her as she practiced on the violin.

Maybe in other circumstances this wouldn't have been the way to feel good, but at that moment I needed exactly that: being together with this girl who was silent and just played the violin. I regained my interest in life step by step. I know that I can't use words of pathos, but one has to understand how it was to come back from the camp at the age of 15 or 16, without parents, alone, to have all my connections with the past broken, from one moment to another.

My mother-in-law was very religious, and my father-in-law as well [they were both Jews]. My mother-in-law, Zsofia, was born in a village in Maramaros [today: Maramures, Romania], into a large family, and she was the youngest. Her whole family immigrated to Israel at the beginning of the 1920s. She was the only one who got married and remained here. This means by the way, that there were seven brothers and sisters who went abroad, so my wife has many relatives, but she never knew any of them, never saw them, only knew that they existed, until her retirement. Traveling was allowed by that time, and one could go to Israel. I don't know if my mother-in-law observed her religiousness with regards to praying, but she surely did with regards to tradition. She had a kosher household.

There was an important event that determined our life as well. Chance so ordained that in 1945 my wife's brother, her only brother, who was 20-21 years old, went to Temesvar [today: Timisoara, Romania] to enroll at university. The country still wasn't really fixed, in terms of the possibility of traveling. After a few months I got a telegram to go to his funeral because he had been shot. He was shot on the street. At that time lots of German and Romanian Nazis were walking around, but also Russian soldiers. It was never discovered who did it, the police didn't find out. One could imagine his parents' mood. It was a terrible thing for my mother- in-law; she didn't go out of the house for years, and this had a great effect on my wife as well.

My father-in-law, Izsak Brull, was a ceramic technician. He participated in World War I, he reached Manchuria, China, and there he had his first connections with porcelain. He learned how to make porcelain; he worked in Austria and in a few more places known for porcelain, after World War I. In the end he came home. The fact is that he was the first specialist of the porcelain factory in Kolozsvar, which chronologically and qualitatively, was one of the first factories in Romania. They lured him away, promised him a good salary in order to come to Torda to develop a porcelain factory there. Actually the design of the Torda porcelain factory came out of his head. And he was its patron for many years. He was not a manager but a director. Because he lived entirely for the factory, after the death of his son he buried himself in his work even more.

Their house was right next to the factory. In the end they cut a gate in the wall which separated them, and then he didn't even have to go out to the street to go across. The factory's internal phone line was connected to their house. It wasn't unusual for them to phone him on the inside line at 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning, asking him to come quickly because there was something wrong with the firing. His life was completely interwoven with that of the factory. He worked on Saturdays as well. He believed in God, didn't work on high holidays, and went to synagogue, but he wasn't so religious.

The house had a cellar, and when somebody came looking for my father-in-law - if we heard tapping from the cellar, then he couldn't be disturbed. The father made his son's tombstone. He made a relief of his son's face on the tombstone. This is hard because from porcelain one has to do it a hundred times, because after firing it sometimes shrinks, sometimes doesn't. One has to try again and again until the face comes out well after firing.

I went to Kolozsvar and my wife went there as well as a student at the conservatory. I was 17-18 years old when I went to university. She came later. We got married in 1952. There was no rabbi at our wedding, only the mayor married us. Our child was born when she was in the 5th year.

My wife observes much fewer traditions; in fact she doesn't observe the traditions at all. I'd say that I am the one who insists sometimes. She doesn't defy me, but there is no initiative from her. She hasn't lived a religious life. We didn't go to synagogue for many years. It was quite an atheistic atmosphere. I wasn't scared, because nobody would have noticed it anyway, if I had gone, but we simply weren't religious.

Tradition in my case, has an ethnic rather than a religious character. Some may criticize me for this, some may not. This is only a matter of opinion, because I observe only certain religious traditions, not the religion itself. One can be a good Hungarian without being religious.

My son isn't circumcised either. It was all the same for my wife, but I didn't want to have it done. In those times it wouldn't have been easy anyway, because at that time there might have been no place in Kolozsvar for ritual circumcision. I think that even today one would have to be taken to Bucharest, if there was anybody to be taken at all, because I think that no Jewish children, in the strictest sense of the word, were born in Romania for a long time.

My son met a Saxon [Transylvanian German] girl from this area. They talked about getting married. I would have liked him to marry a Jewish girl. Mixed marriage is a different problem, especially Jewish-German marriages. These two nations are as far apart as possible since the Holocaust.

We met with the girls' parents, and her mother said that she would like my son to be married by a priest. She asked if I had any objections. I told her: 'This doesn't depend on me. It depends on my son; he and she are the ones who are getting married. But if you ask me, I am strongly against it. I don't ask them to have a religious wedding, but I don't want him to Christianize. Every one should remain in their ethnic group, if they love each other, they'll stay together anyway.' Thereupon she says: 'Well, I don't have any objections to them getting married according to Jewish traditions. I am very religious and I'd like them to get married before God.' A Saxon woman was able to say that, and allow them to get married in a Jewish way. I wouldn't have been able to allow them to get married according to the Lutheran religion. In the end they didn't get married in either way. They had a civic ceremony. They should just be good people and love each other.

If I'm not mistaken, their child [Sonja, who was born in 1982 in Germany] didn't receive a religious education, wasn't even baptized, but the mother, Gerlinde, my son's wife, had a Christmas tree. They don't observe Chanukkah either, nor any other Jewish holidays, because my son is not religious. I told my daughter-in-law: 'Look, I wouldn't like my son to stay in Romania, because he won't have any future here.' At that time it was such that I didn't know whether I would see him again, but I would renounce him. I said there was one opportunity to make something of himself: Israel.

The child was already born when they went to Israel [in 1984], and they were assigned to language courses, and after that they were sent on special terminology courses. My son's wife is called Gerlinde, a pure German name. Because the mother is not Jewish, the child is not Jewish either. My grandchild is a Jew everywhere in the world except in Israel. In Israel they found jobs, my daughter-in-law worked close to Haifa, in Kirjat Jearim. She was never asked whether she was a Jew or not. Of course they didn't ask, because they respected her very much. But my son didn't have a good time; that was down to his colleagues, not Israel.

When they had been in Israel for three or four months, they got a letter from the German embassy of Israel, saying that they could go permanently to Germany. They didn't understand why. After that they got an answer, that the wife's family was in Germany and this family had arranged it, as the woman was of German origin. They found out that Gerlinde had already left for Israel so they informed the local embassy. In six months they were already in Germany. My son is a physician, his wife is a designing engineer at a company; they live a life of ease. My son presented himself to the religious community there, but he doesn't have any function.

I have joined the activity of the religious community only now, as an old person. I simply have time for it and I'm disposed to help them, but not on a religious basis. I was a paying member of the religious community all my life. A great number of non-religious activities became interwoven with the community's life. My activity includes, for example, that it was I who assembled the club-library of the Jewish community, and they also asked me to do some temporary tasks, besides.

There is an organization in Bucharest, the organization of the ex-deported, which is like an organization for the safeguarding of interests. Because I wasn't only in Buchenwald but also in Auschwitz they asked me if I would be disposed to participate in the Romanian Auschwitz committee, in order to represent the Transylvanian [now Romanian] deported, if there were a commemoration in Auschwitz. The whole thing is not religious, even though it is arranged by the Jewish community.

Nowadays in Romania, the Chief Rabbi of the whole country has fewer parishioners then the orthodox pope of Szamosujvar [Gherla, Romania]. In Kolozsvar there were 18,000, in Nagyvarad [Oradea, Romania] 30,000 Jews before the war. There were Jews in Dezs [Dej, Romania], Torda, everywhere. Now there are exactly 400 Jews in Kolozsvar and the community has 800 members; the non-Jewish family members are also considered members of the community.

Where there are larger Jewish communities there are Jewish cemeteries, but they don't bury a gentile in the Jewish cemetery. In the last few years they wanted to procure, with success, something that was the opposite of a centuries-old tradition. Separation was always the centuries-old tradition of the Jews: there were only marriages between Jews. They got married inside a nation of the same religion. They expelled themselves, religiously, from society. After World War II mixed marriages became very frequent, and in mixed marriages it became more frequent that they [the children] remained Protestant or Catholic, especially under communism.

Now they tried to develop in Kolozsvar a new part of the cemetery where they could bury the relatives of Jews in order not to separate them in death. They violate the centuries-old tradition with that. Here they do it because they are very few in number. So the separation became that they [the Jews] became disposed to budge. What they do, is that they bury the Jew according to the Jewish religion and they bury the other person right next to that. Now there is more openness, they invite priests of different religions, e.g. for holidays, to get to know them. Separation isn't good anymore, because if they separate now, they will disappear.