Lasar Blekhshtein

St. Petersburg

Russia

The interviewer: Anna Shubaeva

Lasar Isaacovich Blekhshtein excites unstinted admiration because he is really hale and hearty, notwithstanding the fact that at the age of 8 he lost his leg and since then walks on crutches.

At present he is about 100 years old and he is able to fulfill exactly 100 push-ups.

Lasar strictly follows the rules of healthy life-style (information about it he had picked up from the ancient knowledge of yogis many years ago).

But after several hours of conversation you understand that hardships of his life and life of his relatives had strongly touched him and were seared into his memory.

The last misfortune (recent death of his beloved wife Gede) must have knocked him down, but Lasar, a man of spirit manages to find pleasure in his great-grandsons against everything.

- My family background

I was born in St. Petersburg in 1911. I managed to know something about my ancestors thanks to one very distant relative. His hobby was genealogy and he was engaged in it all his life long. He publishes articles in Russia and in America. He traced his own family back 5 hundred years and at the same time he found interesting facts for me. You know, Jews were authorized 1 to live in large cities, including capitals only since 1863; the privilege was given to college-bred people, very rich ones and handicraftsmen.

For the 1st time our surname was mentioned right then: it was spelled Blekshtein. One of those Blekshteins was a tinsmith, another one was engaged in veneering. Possibly one of them was my great-grandfather (or grandfather), but I cannot prove it.

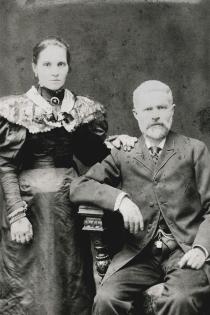

My own information is connected with the photos I have in my album (the small album full of old photos came to me from my relatives). There are photos of my grandfather and grandmother, probably they were my father’s parents (unfortunately I do not know exactly), and also photos of my Daddy and Mom.

I know that my grandfather from that photo worked somewhere on a railway; and Mom told me with pride that he had invented an original lantern. I guess his creative abilities came down to me, because I also appeared to become a modest inventor.

Mom never spoke about her ancestors, therefore I knew nothing about them, including all her relatives. Only from that enthusiast of family trees I got to know that I had got an aunt (Mom’s sister) and her name was Tsilye!

I suppose that my both grandmothers were housewives. I also understand that my maternal grandfather’s name was Solomon, because my Mom’s name was Rebecca Solomonovna (in Russian 2 Rebecca Shlemovna). It seems to me that her maiden name was Kaplun, therefore my maternal grandfather was Solomon Kaplun. And my paternal grandfather’s name was Lasar Blekhshtein (I was named in honor of him as is customary among Jews).

I guess my father was born in Vilno [Vilnius at present, capital of Lithuania], and later his parents moved to Petersburg. Unfortunately I know very little about my father: Mom did not tell us and we (my sisters, my brother, and me) did not ask. Maybe my sisters and brother knew more, but I was the youngest among them and my father died in the year of my birth (in 1911 when he was about 40 years old). It is easy to count that he was born in 1860s.

My father’s name was Isidore (his second name was Isaac). My sisters and brother took Isaac for their patronymics (the same with me), though Isidore would have been more correct (in his birth-certificate Isaac was in brackets). Daddy was a shoemaker.

And unfortunately he got into trouble: he invested all money he had into the co-operative he worked at. But the co-operative went bankrupt and father was crushed down. Mom explained me that it resulted in his stroke. That was all.

My father was buried at the Preobrazhenskoe (Jewish) cemetery [the Jewish part of the Preobrazhenskoe cemetery was opened in 1875]. But Mom never told me about the details of the ceremony.

My Mom’s name was Rebecca (Ginde Rive) Blekhshtein, her maiden name was Kaplun. She was born in 1870 (I counted it, because she died in 1942 at the age of 72). She was religious: attended synagogue on holidays. I do not know whether Daddy did it (Mom told nothing about it). Mom belonged to Misnagdim (a Hebrew word meaning opponents). [The term Misnagdim is loosely used by Hasidim to refer to European religious Orthodox Jews who are not Hasidic 3.

I know that my Mom also came from Vilno. Mom and Dad got acquainted there. But I have no idea about the circumstances of their acquaintance. They arrived in St. Petersburg having already been married. I do not know why they appeared in St. Petersburg. Possibly there they expected to find a large labor-market for handicraftsmen.

- Growing up

In Vilno Mom worked as a senior shop assistant in the department of small wares. Probably that was why she could speak a little a lot of languages: German, French, Polish, Yiddish, and Russian. She had to accept the goods brought from different countries: France, Germany, Poland, etc. Mom told me that her Lithuanian was poor, but Polish was rather good. At home when she wanted to keep something in secret, she spoke French to my sister. But her mother tongue was Yiddish, she often spoke Yiddish to me, and I gave her answers in Russian.

Father died, and mother remained a widow with 4 children. Her life before the revolution of 1917 4 was terrible (she told about it herself). Five of us lived in a small room together. I remember the room though I was very little. I also remember the fire, and my mother pulling me out: I remember very long corridors of that communal apartment 5.

When Mom lost her husband, she immediately lost the right to live in St. Petersburg. Every week a police officer visited her to take a bribe. That was the way we lived before the revolution, but after it Soviet authorities gave us an apartment.

I also remember that during the revolution we often were hungry. A Jewish orphan asylum was opened at that time. Together with the orphans my brother, one of my sisters (middle) and I left Petersburg for Ufa (the Urals). Many years later, being already an adult, I realized that there we had seen cossacks 6 (people on horses). I guess we got there right during the fights of Chapaev brigade 7, but at that time I did not understand it.

Mom had no profession, therefore she worked at the market. She had a small stand there. For about 2 years she boiled soap (I remember it was white with dark blue strings), cooled it, cut it into pieces and sold at the market. Later she started buying and selling different things: soap, blue dye, etc. She earned little money, but she earned it. My brother also was engaged in trading (instead of studying). But in 1920s NEP 8 was abandoned by authorities.

We were often hungry: I remember myself standing beside Mom when she was frying potato pancakes (made from potato peel) on oil stove. It was a pleasure for me to wait for the next pancake. At present Mom often comes in my mind as an expert in cooking. I never ate gefilte fish cooked better than she could!

Mom was a very noble woman. Soviet authorities gave us a three-room apartment, but we lived in one rooms (for some time the second one was occupied by my sister and her husband, and the third one was empty and cold). We kept odds and ends in it.

One day in 1927 my dear Mom walked along Kanonerskaya Street [situated near Lermontovsky prospect] and saw an elderly Jewess and a girl sitting on the sidewalk. She started a talk: Fun wanen zeiter? (Where are you from?), etc. She got to know that they ran away from pogroms in Belarus, lived in need and had no place to spend the night. And Mom took them to our place and gave our cold empty room at their disposal.

They turned out to be provincial Jews with bad manners. They were ungrateful. At first they lived in out apartment without registration, but soon they got registered without our knowledge, and we lost our room (our apartment became communal). Soon they became three, and later the old woman’s son appeared.

So they lived in our room (about 16 square meters) four together. When they opened their door, something unpleasant emitted a smell. For our family it was a tragedy, a great discomfort. My Mom did her Jewish duty and in a better world (beyond the veil) she would be granted remission of forty sins.

After all our torments we had to change two our rooms for another one, dark and terrible, but in another apartment. Mother did not discuss it with her children: I was a schoolboy, and my brother and sister thought it was a temporary measure. You see what happens sometimes to polite and sorrowful people… People say that kind acts cannot be passed over as a mere trifle. That was the way we lost our apartment.

We often moved from one apartment to another. Since my birthday, I lived in 8 or 9 apartments. I was born on Vassilyevsky island [the biggest island in the delta of the Neva River]. I remember our apartment near the Great Choral Synagogue [the Great Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg was built in 1893]. I consider that district of Leningrad to be Jewish (a lot of Jews lived near the synagogue).

Most of the Jews around the synagogue were handicraftsmen, employees, small traders, etc. - in general there were not many intelligent people. I describe the situation of 1920s and 1930s. Later people became more educated: for example, all my schoolmates received higher education. In our class there were 16 Jewish boys, and only 1 of us married a Ukrainian girl, i.e. a girl of different nationality.

I never wore a kippah; Mom forced me to wear tzitzit, but after a year I got rid of it, because I became more independent and was able not to obey Mom. I never had payes, I was always close-cut. Even the older generation did not wear Jewish lapserdak (old-fashioned floor-length frock-coat), but a lot of them were bearded.

Every day on my way to school I met people going to the synagogue. They usually carried tallit and other necessary things for praying.

Our family was rather poor, but not dirt poor. I remember that I was dressed badly, my clothes were the worst in my class. But at that time people did not pay attention to it. You see, my clothes suffered much because I used a crutch, and it rubbed against my trousers. As Mom had no time to patch, I had to do it myself and managed to repair my clothes.

My mother had got 5 children. One of them died being a baby and we never spoke about him. So I had got 2 sisters and a brother, I was the youngest.

My elder sister Elena was born in St. Petersburg in 1898 (you see, I do not know when my parents arrived in St. Petersburg, but I know that she was born here). My second sister Elizabeth was born in 1904; my brother Solomon was born in 1905. And I was born in 1911.

My elder sister Elena got married at the age of twenty. Her husband’s name was Aron Sust, he was a Jew. But he never visited his relatives. Never. I do not know why. Possibly he was a man of bad temper. I lived with Mom and my second sister Elizabeth. Elena lived with her husband in their own room (in another street), and she never came to see her mother, never brought her anything. As for me, I visited Elena many times.

Aron worked as a mechanic: he repaired sewing machines and typewriters. He made a lot of money, but I never saw him with a book in his hands. My sister also was a housewife and nothing more, but a very loving mother and a good wife. She was a real cordon bleu. A good wife, a good mother… But there happened a misfortune: she smothered a baby in her sleep.

Elena was very tired, went to bed and the baby was sleeping beside her. She turned over on her side and pressed the child against the bed. Elena’s husband loved their children very much, therefore that loss made things difficult for their family (Aron considered it to be an inexcusable sin). They had got two more children, two girls: an elder one Vera (born in 1928) and a younger one Elizabeth (I do not remember the date of her birth).

My second sister Elizabeth had a bad fall in her childhood (I guess at the age of 12) and became humpbacked and very short. She did not finish a school and did not get married. She worked as an accountant at a bank. Elizabeth read much, but had sullen disposition. She read in Russian: neither my sisters, nor my brother knew Yiddish (even the alphabet).

During 3 years I did not talk to my brother, trying to persuade him to study at the secondary school. I told him that Soviet authorities allowed us to study, we got an opportunity to study and we had to study. But my brother stood his ground and refused. So he finished only 2 classes. He was able to write and read, but he did not want to read.

My brother was dandyish: it was important for him to have two suits for each season (one for working days and one for days off), and he managed to have. Pay attention that I had got only 1 suit and wore it all the year round. Solomon liked to dress well, liked jolly crowds. But I remember no interesting persons or Jewish intellectuals among his comrades. At that time (in 1920s) it was in fashion to have parties. They used to gather every week. There they mixed with their equals, got acquainted, and married. I was never present at those parties: at that time I was too little and they did not invite me. They never arranged parties at our place.

During the NEP period my brother became interested in trading and got a small stand at the market. He sold fancy goods there. Later NEP was abandoned and in 1930 or 1931 he arranged manufacturing of woolen caps and scarves together with his friend, a Jew. They bought a knitting machine and hired a worker (a woman). That woman had no place to live, therefore we invited her to live at our place.

My brother and his partner registered her as a homemaker (I guess it was cheaper, than to register her as a worker). To cut a long story short, it was illegal. Both of them (my brother and his partner) were condemned for their crime. His partner managed to escape and ran away to China (together with his family). And my brother was brought to prison, and later to a camp. He spent two years there.

Till now I suffer, because I did not send my brother parcels while he was in prison and in the camp. Two years I sent nothing to him. You see, I was a student, I was poor, but now I think I was able to send a parcel to him! That idea did not come into my head and nobody suggested it: neither Mom, nor sisters. We acted like strangers, not relatives. We were wrong. It was necessary to send him a lot of cigarettes, so that he could change them for food… Unfortunately that cannot be remedied.

Later when he returned from the camp, he worked as a bookkeeper. You see, he was not educated, but very clever: he managed to finish courses for bookkeepers and worked as a senior bookkeeper at KIROVSTROY! The Kirov factory [The Kirov machine-building factory was founded in St. Petersburg in 1801] was a great factory! They had got a special building organization engaged in construction of new factory workshops: it was named KIROVSTROY. My brother was the Head of that organization and had got 6 subordinates. I guess he could have come to the forefront, because he was more talented than me. But he did not study…

He got married. I do not remember her name. She was a Jewess. As my brother wanted to be better and better circumstanced, his wife had to have abortions (one after another) until he got a room, furniture, cut-glass ware, clothes, etc. In the issue they had got no children. So they died having no children.

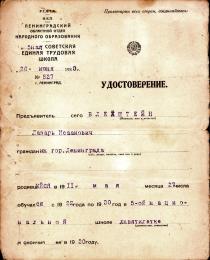

I studied at the National Jewish school #5 9. Mom sent me there. They did not teach us religion. In our class there were 8 boys and 8 girls: only Jewish children. At school there were 10 classes (about 200 pupils). All teachers were Jewish. They taught us Yiddish among other generally accepted subjects. At our school only 2 cleaners were Russian.

At that time in the city there were 5 national schools: 2 German (Annenschule, Peterschule), Greek, Polish and Jewish. The Jewish school was situated in the former gymnasium of Eizenshtadt in Lermontovsky prospect (close to the synagogue: our back door opened into the synagogue court yard).

I finished that school and I am very proud of it. In 1929 in Leningrad authorities initiated campaign for estimation of training quality and potential of pupils, i.e. investigated students’ IQ. And our school appeared to be the 2nd in the city after Annenschule.

By the way, students from Annenschule and Peterschule were from rich families: governesses saw the children to the school doors, tutors helped them in their studies, etc. And our school was a school of beggars, we were beggars. I finished my school in 1930. It functioned 20 years and was closed after our graduation.

By the way, I started my school years on September 1, 1921 and on September 30 of the same year I got under the wheels of tram. I lost my leg and since then I walk on crutches. Therefore I missed the whole year (I spent it in hospital) and continued my studies at school only a year later.

Our school was perfect! Here I’ll tell you about our director Timofey Yakovlevich Tseytlin (I do not remember his Jewish name, but I remember that it was absolutely different). He taught us social science, trained us to be good people and told us about everything. Here imagine a fine day in May, our studies are almost over. Do you think it was possible for a teacher to arrest attention of 16 boys and girls aged 16-18? Yes! He fell into talk and had been giving a lecture for 6 hours without any break.

We were so much taken with the topic that even did not leave the classroom for toilet! He was a person of encyclopedic knowledge: he was able to speak about Middle Ages, about Indians, about China. He also knew much about Jewish societies (at that time Israel did not exist). We listened and he spoke. He was a born orator! I bend my knee before him!

And his wife Lubov Sergeevna was a short slightly built woman. She taught us chemistry. But… we did not like chemistry: nobody of us (16 pupils) became a chemist. Most of us chose engineering.

Mark Yakovlevich Shnitsler taught us physics. I think he was not talented in teaching. Our Maths teacher Abram Efimovich was perfect, though he was a doctor by profession. Humanitarian subjects (History, Literature) were taught very well. Our teacher of German language knew 7 languages (her name was Anna Ossipovna Pinsker).

They taught us Yiddish (we knew nothing about Hebrew) like all other subjects: German, Geography, Maths. At that time I could read Yiddish. At present I remember the alphabet, but I cannot read: I spell out (my English is much better), but I write easily! Four times my neighbors came to me and asked me to translate letters from Russian into Yiddish. They sent my translations to America and got answers: it means that people understand my Yiddish. Yes! I can write quickly.

Mom did not help me in my studies. You see, she worked in the market. One day a teacher from our school saw her there. She bought something from her and said ‘Your boy is a capable pupil and you should not worry about him.’ So nobody paid attention to my studies: neither my sisters, and brother, nor Mom.

In our class there were several intellectuals: for example, a son of one of our teachers (Yiddish language teacher). He became a professor later. And the majority of us were kapsonim (like my family). Kapsonim means beggars (according to Sholem Aleichem 10).

In fact nobody of us attended the synagogue. We (boys) used to run to the synagogue at Simchat Torah, because at that time they gave us gifts, and we competed (tried to receive as many gifts as we could). I walked on crutches, therefore they felt sorry for me and I got more gifts than others. I was very proud of it. They usually gave us sweets, gingerbreads, but it was not our aim, we acted for the fun of it. We were boys of 12-14 years old.

A lot of religious people attended the synagogue. I remember that at that time there were 3 synagogues: the Great Choral Synagogue, the synagogue of Hasidim (now it is called the Small Synagogue), and the synagogue of Misnagdim (inside the Great Choral Synagogue on the 2nd floor). During holidays all synagogues were full of people. And I do not remember any conflicts.

My Mom attended the Misnagdim Synagogue, and I used to bring her something to eat while she was praying. My brother and my sisters never visited the synagogue, and I attended the Great Choral (for me it was more interesting).

In the Great Choral Synagogue the first rows (about 20) were places for gvirim, i.e. for rich people; each of them had tallit bordered with gold and silver. It was impossible to have a seat there: people bought places a year beforehand (like in the Philharmonic Society). And it was expensive (I do not know how much).

There were a lot of Jews in Petersburg: I know that they were about 220,000 before Perestroika 11 and at that time they were much more. The farther from the 1st row the cheaper the seats. A lot of people had to be standing. If I came, I stood in the crowd. The synagogue hall was overcrowded.

Once in my life (I was a 12 years old boy) they trusted me to carry Torah, though I was on crutches! I carried Torah, and people touched and kissed it. That was my affecting experience.

We did not celebrate my bar mitzvah, but I remember the following. In the city there were several synagogues situated at private apartments, where religious Jews gathered to pray. One day Mom sent me to one oа those apartment on some business (she used to send me to different places: to shochet with a hen, etc.). I remember it was in June somewhere in Sadovaya Street, in the big apartment. I came in and saw people walking around the flat like sleep-walkers. As soon as I came in Jews rushed to me ‘The boy! How old are you?’ - ‘I am thirteen.’ - ‘Oh!!!!’ And they clamored at once. You see, I was the 10th Jew (minyan) and they could start praying. It was good that the 10th Jew came, though I was only a boy.

My mother forced me to go to cheder. It was here in Petersburg in 1926-1927. Mother wanted me to study Jewish Tradition, because she was a religious woman. But I haven’t learnt much there: it was not very interesting for me. Later for some reason the cheder was closed. But Mom was very persistent: she invited rabbi from the cheder to come to our place (she paid him).

He came, we read. We read in Hebrew, but I understood nothing! He read and translated. It was Humash or something of that kind: I do not remember. I also do not remember the rabbi’s name, we called him rabbi. I guess he was rather poor: he used to have dinner with us. Rabbi visited us during a year. But I was interested in Russian literature (classical). Therefore I appeared to be an underachiever and he stopped our studies. He was very nice, and I distressed him. At that time I wore tzitzit (Mom forced me). At our school nobody did it, but in cheder there were boys with payes (their parents insisted).

We finished our school in 1930. All my schoolmates started working in different spheres. Some of my friends became turners and mechanics, and I found job of a copyist at a design office.

Here I’d like to tell you that our teachers brought us up ideally: all of us became honest people, nobody of us broke the law. Almost all of my classmates have already died. All of my classmates avoided camps 12 - and it was surprising; because in 1937 13 people suffered much. Several boys served in the army. During the Great Patriotic War 14 one of them was lost.

Our teachers were professionals, therefore fifteen persons from our class (even the most slow ones) graduated from different colleges and became engineers, geologists, meteorologists, etc. And one of us (the 16th one) did not manage to receive higher education, because he was executed by shooting before 1937. Here is the story about him.

That boy was the most intelligent of us, he was from an intelligent Jewish family. His father was a bookkeeper at the Synagogue. His father was one of the Twenty [an initiative group of 20 religious persons got registered and was able to sign contracts on using religious buildings, and solve other problems connected with exercise of religion]. My schoolmate’s name was Emmanuil Kitainov, and we called him Nolik (Zero). He was talented in the humanities.

At our school there were two good reciters of verses: Nolik (he was the 1st) and me (I was the 2nd). Nolik was very good in Russian, but he was ignorant in mathematics and physics. In the 9th form he was asked to count the volume of the cube (its side was equal to ‘a’). Nolik thought for a long time, but managed to answer that it would be ‘а3’. Then the teacher changed the problem specification from ‘a’ to ‘a/2’, and Nolik gave no answer. But! He was the only pupil at our school who knew Hebrew!

His parents were grateful to me, because at school there were savage customs and guys used to play tricks on Nolik. Once they forced him to climb upon a bookcase. The bookcase was not high, but Nolik could not climb down and stayed there. I also remember that they often put Nolik into a garbage box (at school there were special boxes for rubbish), and again Nolik made no attempt to get out. It was me who often came to his succor. His mother was extremely grateful to me.

We finished our school and stopped to be in touch. But in 1934 he was brought to our mind. In December 1934 Kirov 15 was killed; the next day we read in the newspaper that 16 people were shot (in revenge, I guess), and among them we found Nolik’s name. How did he get there?! We lost ourselves in conjectures. By hearsay we got to know that he studied in some library.

We suspected that he was connected with keeping or distributing unauthorized books and in the end of 1934 he was in prison. He was taken among other prisoners. He was innocent.

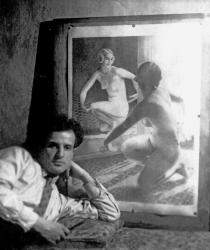

After school it was necessary to find a job. When a schoolboy, I studied at the art school and finished it. I doubt that I had any creative abilities, but I had been studying drawing for 3 years and received a diploma. I decided to become an engineer, and appeared to be a good draftsman (my studies at the art school helped me much).

But at that time it was very difficult to enter a college: it was necessary to have worked for 2 years before entrance exams. All my classmates (I already told you) found their work at different factories as turners, mechanics, etc. But it was impossible for me because I had only one leg, therefore I found job of a copyist at the design office at ELECTROSILA factory [Electrosila Factory is a Leningrad Corporation for construction of electric machines – one of the largest USSR factories in this sphere.] Half a year later I became a draftsman (designer).

At ELECTROSILA they arranged the first Special Design Office in the USSR. Different people were taken to the office: 6 persons from ELECTROSILA factory, several dozens of arrested doctors and professors. A General was the office chief. For fulfilling ordinary (simple) tasks they sent there a lot of students of Electrotechnical College. [The Electrotechnical College was founded in 1891.]

Those people designed 2 mighty projects. I was so sorry that at that time I had not enough knowledge to adopt their practices and methods.

At that time they also arranged evening courses at ELECTROSILA (a branch of the Electrotechnical College). I had no chances to enter it: my brother was in prison, and Mom was a handicrafts person. At that time my nationality was not an obstacle for entrance; but the facts from my biography were.

Those learned scholars finished their work in 1932 and the Special Design Office was closed. The former chief presented me a set of clothes for my good work. You see, at that time it was a problem to buy clothes (even a handkerchief): everything was on cards 16 and salaries were crummy. And the General gave me a lot of things: from socks to winter coat, caps, suits, etc.

But I thanked the General and said that I wanted to study: ‘You know my biography, I never made secret of its facts. I guess they will not let me enter a college.’ - ‘Why didn’t you submit your application?’ - ‘It is useless.’ He answered: ‘Do it.’ And I handed my documents over to the College entrance examination. Later I did not find my name in the list of new students. I came to the General ‘They did not take me, I told you.’ The General gave me a petition (from GPU 17). It was GPU that killed millions of people under the guidance of Stalin. It was terrible (at that time people used to say that half a country was in camps and half a country was on duty). With the help of that paper I entered the College (evening course).

Soon I found out that our training there was inadequate, therefore I continued as a full-time first-year student of the Polytechnical College. [The Polytechnical College was founded in 1899.] I graduated in 1937 from the faculty of measuring technique and started my labor activity.

At first I worked at LENENERGO [the power company of St. Petersburg]. Graduates had to complete a mandatory 2-year job assignment 18 issued by the college from which they graduated. But I graduated with honors, therefore I was allowed to get employment at my discretion in any town or organization. I chose LENENERGO. They had got no service of measurements, and I started working at the department of automatic equipment.

My future wife came there to work, too. Her name was Gede Israelevna Kaplun. At that time she was 26 years old (she was a year younger than me: born in 1912). Her parents had got 3 daughters: Ida, the youngest (she is still alive), my Gede, and Ella, the eldest (she has already died). It was a Jewish family, they arrived in Petersburg from somewhere, I do not remember the place. I did not know their father (he died earlier), but I was acquainted with their mother.

She had a great deal of personality, was independent and strict. And she brought up her daughters in her own spirit. She was not religious. Their family was of average culture. My wife, for example, was not widely-read. But she was a clear head, a good expert and she was equal to the tasks of mother and wife.

We got acquainted in 1938. She graduated from the Electrotechnical College and was an electrical engineer. She understood that I was an indecisive boy-friend. So one fine evening I heard a doorbell. It was about midnight, and I usually went to bed early. I had a room at the communal apartment and my neighbor opened the door for her.

She understood that I was that sort of idiots whom it was better not to talk to much, she came in, undressed and got to my bed. Our loving relations lasted 66 years, we lived in harmony. Only one misfortune: she passed away before me (several years ago); though women usually live longer than men.

When we got married, my wife was already going to give birth to our first child. LENENERGO gave us a room (5.5 square meters). Can you imagine that I managed to place there a sofa, a large desk, a wardrobe, and 2 armchairs. I visited a furniture store 3 times to measure the pieces of furniture. All my neighbors came to our place to look what I managed to do!

The chief engineer of LENENERGO Sergey Mihaylovich Pussin was one of my benefactors (it happens not often in our life!) - may he rest in peace! When my wife became so great with child that she could not squeeze between the sofa, the wardrobe and the desk, Sergey Mihaylovich gave us charge over the room.

He had no right, because the room belonged to the LENENERGO department! But it happened and we got a possibility to change it for another one. We managed to change it for a room of 12 square meters and it became a little bit easier for us.

By 1941 our son was 10 months old. His name is Erlend. Erlend is a Norwegian name. You see, my wife Gede read a novel by Norwegian writer Sigrid Unset [1882-1949]. She received (to my knowledge) a Nobel Prize. Erlend is a hero of her novel Kristin Lavransdatter. My wife read the book and named our son Erlend. At home we called him Eric. He has got only one name (like the rest of my sons): nobody of them has Jewish name.

One clever famous Frenchman recommended people the following: if you want to know a person, give him 2 sheets of paper and ask him to write down all his good deeds (on the 1st one) and all his clever deeds (on the 2nd one). As for me, I’ll recommend to give a person the 3rd sheet of paper to write down all his silly deeds.

My list of silly deeds would be much longer than 2 previous, I am sure! But one of my cleverest ideas (I am proud of it!) came to me before the war. I analyzed information from newspapers and understood that the war was going to burst out very soon.

- During the war

I worked at LENENERGO, and one of my friends worked at the sales department. They defined quotas, therefore they could get everything by pulling strings. I asked my friend to order tickets for me. So next day (absolutely unexpectedly for my wife) I came home and brought her railway tickets. I saw my wife and our son off on the train. They left Leningrad on June 6, 1941. And the war burst out on June 22 (2 weeks later). I consider that my action to be one of the cleverest or even the cleverest in my life.

I sent my wife to her sister Ida. She and her husband were geologists and at that time worked on construction of some power station (I do not remember what power station).

My wife was very clever and active, while her sister, on the contrary, was not so active. So Gede moved her sister and her family to Tashkent [nowadays it is the capital of Uzbekistan; and during the Great Patriotic War it was a place of evacuation]. There she managed to find job of a teacher at the technical school and got a room somehow. [Technical school in the USSR and a number of other countries was a special educational institution preparing specialists of middle level for various industrial and agricultural institutions, transport, communication, etc.]

I remained in the besieged Leningrad 19 and suffered from starvation: my weight was 32 kg when I left the city in February 1942. LENENERGO gave us a bus and we moved along the Road of Life 20. I traveled about a month and in March reached Tashkent. When my wife saw me, she nearly fainted: I was a bag of bones. In Tashkent people lived not very well, but they could eat normally. I worked there at the design office of a factory which produced electric lamps. I was a chief designer there.

My Mom, my sister Elizabeth, and my nieces (Elena’s children) stayed here in Leningrad. Elizabeth took care of them.

Elena’s husband was lost during the first months of the war. From rumors we got to know that on the Volkhov River their barge turned over and all passengers were lost. So he did not fight. Later (in 1942) Elena was killed during bombardment. She worked at the Kirov factory (wanted to get a worker’s ration card). She was buried in the Daddy’s grave. No Jewish ceremonies. I was present at the ceremony and I remember that we all were silent. I am distressed with it now.

My brother Solomon was at the front-line twice: he took part in the Soviet-Finnish War 21 and in the Great Patriotic War [WWII]. He fought from the very first day till the very last one. During the World War II he served on the Far East as a lieutenant (though I am not sure). Solomon managed to remain alive, he even was not seriously wounded. He was awarded an Order of the Red Star 22.

I could not take my relatives to evacuation with me: the bus belonged to LENENERGO (therefore only its employees were permitted to go, no relatives). I also was not sure that our bus would be able to reach the continent: I knew about trucks which had broken through the ice on the Road of Life. I addressed the local Communist Party committee and they told me that they were going to evacuate a lot of citizens very soon.

I calmed down my relatives: I told them about their forthcoming evacuation. And indeed, they left the city soon. But unfortunately by that time my mother had died. It happened on March 8, 1942 (therefore March 8, the Women's Day is not a holiday for me, but a dark unforgettable time). And Elizabeth and her nieces left for the Urals. They returned to Leningrad (to their apartment) after the end of the war.

In Tashkent my wife gave birth to our second son. It happened in 1943. We called him Simon. Why Simon? Why not Solomon (in honor of my brother)? You see, we were not sure that my brother was alive. Therefore we wanted to call our baby not Solomon (in case my brother was alive), but we wished the name to sound similar. That was why we called our son Simon. Since that time we called my brother Monya and my son Sima. We returned to Leningrad after the end of the war and in 1946 our third son Boris was born.

My wife refused to have abortions. It was in her character. Therefore everybody around us (including our director and the chief engineer) had got one child, and we had got three of them. They considered us to be crazy. I did not dare to insist: I would have never forgiven myself any tragic mischance with my wife during abortion. And she loved our children very much and devoted her life to them.

- After the war

You know, it was a problem for me to get back to Leningrad after the end of the war 23. My wife returned, but the factory administration did not want to let me go, because I was one of the leading designers. Later I was appointed a shop superintendent. It was necessary to find a replacement, so I managed and then they let me go. I got to Leningrad via Moscow.

We lost our room: leaving Leningrad I simply put my key under the rug near the front door. And when we arrived, we could not get inside the room: it was occupied. Everything was awfully difficult. Some time I worked not in compliance with my profession, and later (in 1948) I found job of designer at the Vibrator factory. I worked there from 1948 till 1984 (36 years).

Vibrator factory produced electrical measuring instruments. At that time there were 5 different types of instruments and I was the chief of design office for one of those types. I had got 18 subordinates. We worked upon a model of the instrument and handed it over to the factory where they produced instruments after our example. I invited hard-working people to the office, all of them were professionals. We were not close friends, but I remember that we celebrated someone’s birthday together (I do not remember exactly).

Jews worked in our office, too. But most of our employees were Russian. We worked and our administration board was satisfied with our work. Our instruments were on sale abroad.

By the way, the factory director and the chief designer were Jews. Our team was very efficient.

I never paid attention to nationality choosing friends. At school my friends were Jewish, because my school was Jewish. At my College there were many Jews. I did not do it on purpose, though I felt some drawn to Jews. But there was no religious aspect in our relations. We did not celebrate Jewish holidays (at school we did, but because our parents attended a synagogue.) All Jews I knew in my life knew nothing about Talmud or something of that kind. Some of them knew about Hummash.

Here are the results of my life activity: 5 books, 19 articles, 32 inventions (for 10 of them I got copyright certificates and received some money).

Using my inventions, 2 persons defended their theses and received 'kandidat nauk' degrees 24. I did not need the scientific degree, because I earned money for my family, working on inventions and books. Using one of my inventions a group of my colleagues received the State (Stalin’s) Prize. But as I was a Jew and not a communist party member, therefore I was not in the list. The same happened with my friend in 1948 and he went crazy. As for me, I did not sleep 3 nights: the situation was so insulting! You see, a good idea comes to you not every day.

One day Einstein was asked about the way he got his brilliant ideas: ‘Do you file them or keep a diary?’ Einstein answered ‘Oh, good ideas appear so seldom!’ You see, those people received the State Prize for the work I was thinking about during 8 years (and it was my fourteenth variant of solution)! But I was easy to get round. When I understood everything and recollected that my friend, I did my best to remain alive: I used yoga exercises to avoid stress results. I think that life is life and the prize is nothing… At present I often watch my instruments on TV (every month in different programs!).

I had got three sons, hence it was necessary for me to have four apartments. I managed. For example, this apartment, I got for one of my inventor’s fees: I solved the problem that people have been trying to solve for a long time (since the 19th century).

A new device I designed in 1956. Once I talked to Americans, and they told me that in their country my invention would have cost half a million dollars! Here I did not received half a million dollars, but I got an apartment: and it was very good (it was extremely difficult to receive a new apartment, I had to become a member of a building society and pay for the apartment!).

My successful inventions disturbed the good understanding between my brother and me: he was unkind to me… A close friend of mine explained to me that I had hurt the feelings of my brother by presenting him my book with an inscription ‘To my dear brother from one of the authors.’ For me it was normal, but for him it was a misfortune. You see, he never wrote a word, and his brother wrote a book!? I guess if someone somewhere solved a difficult problem and received a million for it, he would not notice it. But if it was his brother, it was a severe hurt to his pride.

Unfortunately my brother hated me. When I visited him, he usually left the apartment supposedly to buy ice-cream. But he did not come back in my presence. I guess after my leaving his wife gave him some signals and he returned. My brother could not forgive me my success. You remember that I had got three children, and he did not have any, I received higher education and he finished only two classes… So I stopped visiting him and he came to my place never more.

My brother died in 2001. His wife died several years later.

Elizabeth, my sister died at the age of 72. She was a decent person: during the blockade she took care about her nieces (orphans) after Elena’s death. Elizabeth went to evacuation with them. After their return to Leningrad her private life was very poor, and the children were very difficult… The elder girl Vera was uncontrollable: in evacuation she tried to commit a suicide.

Elizabeth got in the hospital and one day they called me and informed about her death. She was cremated, and I buried her near our father’s grave.

My wife died in 2004. We lived 66 years together with her. And I… I feel fine (like a young boy). I guess my heart worked not so hard because I lost my leg at the age of 8. I am able to stay in a steam room for long and do not feel high temperature.

Let's talk about my children. The elder son Eric graduated from the Conservatory, he is a chorister. We meet seldom. His family is not fine: 12 years ago he lost kidneys, his wife is sick with cancer, his daughter is about 29, but not married, his son got divorced and is not happy with his second wife…

My second son Simon left for Israel 11 years ago. Their life in Israel is not so good now. He is an engineer (graduated from the Electromechanical College), but works as a yard keeper. Several years ago he was a worker at a plant. He has got two girls: 20 and 22 years old. They are my pride and happiness, because they are beautiful, good, and talented! His wife is a chemist. Simon never calls me, his daughters or their grandmother sometimes phone me.

My younger son Boris is my beloved boy. Yesterday we visited a steam bath together. He is an engineer, graduated form the Polytechnical College. 23 years he worked in Norilsk. He often goes to business trips to solve different serious problems at different metallurgic plants: people trust him. He has got a daughter Galina. Her first marriage was not successful; and now they live together with a guy and have a child of 4 years old, but they are not married officially. They often visit me.

My children and grandchildren know that they are Jewish, but they do not live Jewish life. Only Daniil, my grandson arranged manufacturing of matzah (he is a businessman) somewhere in the suburb of St. Petersburg. Last year he brought me 2 kgs of matza. Probably my Israeli relatives understand Jewish life more than we do.

And today I’ll soon congratulate some people by telephone: ‘Gut yom tov! Gut yor.’

- Glossary:

1 Jewish Pale of Settlement

Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times.The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.

2 Common name

Russified or Russian first names used by Jews in everyday life and adopted in official documents. The Russification of first names was one of the manifestations of the assimilation of Russian Jews at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. In some cases only the spelling and pronunciation of Jewish names was russified (e.g. Isaac instead of Yitskhak; Boris instead of Borukh), while in other cases traditional Jewish names were replaced by similarly sounding Russian names (e.g. Eugenia instead of Ghita; Yury instead of Yuda). When state anti-Semitism intensified in the USSR at the end of the 1940s, most Jewish parents stopped giving their children traditional Jewish names to avoid discrimination.3 Hasidism (Hasidic)

Jewish mystic movement founded in the 18th century that reacted against Talmudic learning and maintained that God’s presence was in all of one’s surroundings and that one should serve God in one’s every deed and word. The movement provided spiritual hope and uplifted the common people.There were large branches of Hasidic movements and schools throughout Eastern Europe before World War II, each following the teachings of famous scholars and thinkers. Most had their own customs, rituals and life styles. Today there are substantial Hasidic communities in New York, London, Israel and Antwerp.

4 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.5 Communal apartment

The Soviet power wanted to improve housing conditions by requisitioning ‘excess’ living space of wealthy families after the Revolution of 1917. Apartments were shared by several families with each family occupying one room and sharing the kitchen, toilet and bathroom with other tenants. Because of the chronic shortage of dwelling space in towns communal or shared apartments continued to exist for decades. Despite state programs for the construction of more houses and the liquidation of communal apartments, which began in the 1960s, shared apartments still exist today.6 Cossacks

an ethnic group that constituted something of a free estate in the 15th-17th centuries in the Polish Republic and in the 16th-18th centuries in the Muscovite state (and then Russia). The Cossacks in the Polish Republic consisted of peasants, townspeople and nobles settled along the banks of the Lower Dnieper, where they organized armed detachments initially to defend themselves against the Tatar invasions and later themselves making forays against the Tatars and the Turks.As part of the armed forces, the Cossacks played an important role in Russia’s imperial wars in the 17th-20th centuries. From the 19th century onwards, Cossack troops were also used to suppress uprisings and independence movements.

During the February and October Revolutions in 1917 and the Russian Civil War, some of the Cossacks (under Kaledin, Dutov and Semyonov) supported the Provisional Government, and as the core of the Volunteer Army bore the brunt of the fighting with the Red Army, while others went over to the Bolshevik side (Budenny). In 1920 the Soviet authorities disbanded all Cossack formations, and from 1925 onwards set about liquidating the Cossack identity.

In 1936 Cossacks were permitted to join the Red Army, and some Cossack divisions fought under its banner in World War II. Some Cossacks served in formations collaborating with the Germans and in 1945 were handed over to the authorities of the USSR by the Western Allies.

7 Chapaev Vassiliy (1887-1919)

Soviet military leader, hero of the Civil War of 1918-1920. He was in command of a brigade which played a significant role in the fights. During a battle in the Urals he was wounded and drowned attempting to cross the Ural River. Later he became a popular hero in the Soviet Union.8 NEP

The so-called New Economic Policy of the Soviet authorities was launched by Lenin in 1921. It meant that private business was allowed on a small scale in order to save the country ruined by the Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War. They allowed priority development of private capital and entrepreneurship. The NEP was gradually abandoned in the 1920s with the introduction of the planned economy.9 School #

Schools had numbers and not names. It was part of the policy of the state. They were all state schools and were all supposed to be identical.10 Sholem Aleichem (pen name of Shalom Rabinovich (1859-1916)

Yiddish author and humorist, a prolific writer of novels, stories, feuilletons, critical reviews, and poem in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian. He also contributed regularly to Yiddish dailies and weeklies. In his writings he described the life of Jews in Russia, creating a gallery of bright characters. His creative work is an alloy of humor and lyricism, accurate psychological and details of everyday life.He founded a literary Yiddish annual called Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek (The Popular Jewish Library), with which he wanted to raise the despised Yiddish literature from its mean status and at the same time to fight authors of trash literature, who dragged Yiddish literature to the lowest popular level. The first volume was a turning point in the history of modern Yiddish literature. Sholem Aleichem died in New York in 1916. His popularity increased beyond the Yiddish-speaking public after his death. Some of his writings have been translated into most European languages and his plays and dramatic versions of his stories have been performed in many countries. The dramatic version of Tevye the Dairyman became an international hit as a musical (Fiddler on the Roof) in the 1960s.

11 Perestroika (Russian for restructuring)

Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s, associated with the name of Soviet politician Mikhail Gorbachev. The term designated the attempts to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized, market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratize the Communist Party organization.By 1991, perestroika was declining and was soon eclipsed by the dissolution of the USSR.

12 Gulag

The Soviet system of forced labor camps in the remote regions of Siberia and the Far North, which was first established in 1919. However, it was not until the early 1930s that there was a significant number of inmates in the camps.By 1934 the Gulag, or the Main Directorate for Corrective Labor Camps, then under the Cheka's successor organization the NKVD, had several million inmates. The prisoners included murderers, thieves, and other common criminals, along with political and religious dissenters.

The Gulag camps made significant contributions to the Soviet economy during the rule of Stalin. Conditions in the camps were extremely harsh. After Stalin died in 1953, the population of the camps was reduced significantly, and conditions for the inmates improved somewhat.

13 Great Terror (1934-1938)

During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor.Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public ‘show trials’. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the Party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.

14 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.15 Kirov, Sergey (born Kostrikov) (1886-1934)

Soviet communist. He joined the Russian Social Democratic Party in 1904. During the Revolution of 1905 he was arrested; after his release he joined the Bolsheviks and was arrested several more times for revolutionary activity. He occupied high positions in the hierarchy of the Communist Party. He was a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, as well as of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee. He was a loyal supporter of Stalin. In 1934 Kirov's popularity had increased and Stalin showed signs of mistrust. In December of that year Kirov was assassinated by a younger party member. It is believed that Stalin ordered the murder, but it has never been proven.16 Card system

The food card system regulating the distribution of food and industrial products was introduced in the USSR in 1929 due to extreme deficit of consumer goods and food. The system was cancelled in 1931. In 1941, food cards were reintroduced to keep records, distribute and regulate food supplies to the population. The card system covered main food products such as bread, meat, oil, sugar, salt, cereals, etc.The rations varied depending on which social group one belonged to, and what kind of work one did. Workers in the heavy industry and defense enterprises received a daily ration of 800 g (miners - 1 kg) of bread per person; workers in other industries 600 g. Non-manual workers received 400 or 500 g based on the significance of their enterprise, and children 400 g. However, the card system only covered industrial workers and residents of towns while villagers never had any provisions of this kind. The card system was cancelled in 1947.