Korina Solomonova

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Dimitar Bozhilov

Date of interview: November 2002

Prof. Korina Solomonova is a nice old lady, devoted entirely to her five grandchildren. She talks eagerly and enthusiastically about the history of her family - her mother's side comes from Sofia and on her father's side from Sliven. She is very proud of her scientific achievements during communist times in Bulgaria - she discovered that elderly people over the age of 60 can be immunized against tetanus.

My paternal and maternal ancestors belong to the group of Sephardic Jews who lived in Spain and were banished by the Inquisition five centuries ago. They spoke Ladino. My paternal grandparents were born and lived in Odrin [a town on the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula, now in Turkey]. My grandfather was born in 1860, my grandmother in 1865.6I remember that they knew Turkish very well. My grandfather's name was Solomon Mihaylov Solomonov. He had finished the 3rd year of junior high school, corresponding to present-day 7th grade. He had a small grocer's shop.

My grandmother, Mazalto Mihaylova, was a housewife and devoted herself to looking after the children. She very strictly observed the separation of dairy and meat products, she never put meat and milk together on the table. The food was always kosher in her house. She dressed in traditional urban clothes. I know that my grandfather moved with his whole family from Odrin to Sliven [in southern Bulgaria], because his business wasn't going well. In Sliven he once again opened a grocer's shop, with which he supported his family.

My paternal grandfather was better-off than his father and he managed to build and open a small factory producing socks and blouses in Sliven. After he built the factory, he closed the shop. In order to start production in the factory, my grandfather bought ten hand-operated knitting machines for woollen socks. When my father was 18-19 years old, they bought new machines for the factory and modernized it. After my grandfather, my father ran the factory.

My father, Mihail Solomonov Mihaylov, was born in 1891 in Sliven. His first name was Mishel, but during the repressions against the Jews in the beginning of the 1940s he was forced by the authorities to change his name to Mihail. He studied in a high school, but he didn't graduate. He was the youngest among his siblings. He had two sisters and two brothers. His sisters, Duda and Klara, were the eldest. Duda lived in Sliven. Klara was married in Sofia. She was a very educated and cultivated woman; she had graduated from the high school in Sliven. Klara was a housewife; she looked after her children and took part in charity events.

The two brothers of my father were Leon Mihaylov and Nissim Mihaylov. They were no longer alive when I was born. Leon was a teacher and Nissim was a lawyer. They weren't religious, didn't have any religious books. They believed in socialism and had a lot of Russian literature. They had university education and were intellectuals. They both took part in the Balkan War 1. I don't know why, but I suppose that Leon was a prisoner of war in Tsarigrad [the Bulgarian name of Istanbul] during the Balkan War. Then my paternal grandmother, who hadn't gone to school, but knew Turkish very well, went to Tsarigrad herself and arranged for her son to be released from prison. But he came down with tuberculosis. He was put in a hospital in Vienna and my grandmother again accompanied him there in order to take care of him. He died in the hospital in Vienna before he reached the age of 30, and was buried there. His other brother, Nissim, also died young. He was a very intelligent man. I found many of the books he had read in the basement of our old house in Sliven.

My maternal great-grandfather was a rabbi and lived in Tsarigrad. I know that he had a daughter who married a Bulgarian. In order to marry a Bulgarian, she had to convert to Christianity and that was considered a betrayal. She changed her name to Tsvetanka and the whole family cut off all relations with her. Only after 20 years did some of the family get in touch with her. My great-grandfather thought this was a punishment from God and committed suicide by drowning himself in a well, because he couldn't get over the fact that his daughter betrayed her faith. This shows the incredible faith reaching to fanaticism that my great-grandfather had, who felt guilty for failing to raise his daughter to identify herself as a Jew.

My maternal grandfather, Nessim Kohen, was born in Tsarigrad in the 1860s. I don't know what kind of school he graduated from, but he could read very well in Bulgarian and Hebrew. He was a very educated man. He moved to Sofia and traded textiles. My maternal grandmother, Luisa Kohen, was a housewife. She died young, 56 years old, of typhus during the Balkan War [in 1914 in Sofia].

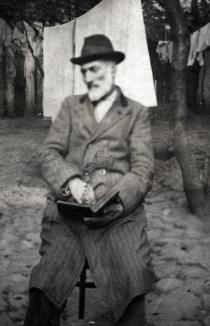

Grandfather was a very religious man. I remember that he was well-built and good-looking, with a long beautiful beard. He observed all religious rituals very strictly. Every night he read prayers, wore a kippah and tallit when he went to the synagogue. From my stays at my mother's family in Sofia I remember that the Jewish rituals were very strictly followed there. The whole family didn't work on Sabbath.

The house of my mother's family is on Opalchenska Street in Sofia. The street is located in the western part of the town near the center and passes through the Jewish neighborhood. The neighborhood was called Iuchbunar 1 and was on the west side of the street. The house is a very beautiful three-story building and it still exists today. My mother's family: my grandfather Nessim Kohen, my mother's elder brothers, Bohor Kohen and his family, Chelebi and Leon Kohen, and my mother lived together in it. The boys were quite a bit older than her, as she was a little girl when they married and had families. The house was big enough to accommodate the families of my mother's brothers as well. It was only my mother who left the house when she married; she moved to Sliven.

My maternal grandfather passed his business on to his sons, but when he had to prepare my mother's dowry, the shop went bankrupt and my uncles started their own businesses.

My mother, Matilda Mihaylova, finished high school in Sofia. She always dressed fashionably. Her family was modern and could afford to dress well. My father's sister, Klara, who was married in Sofia, introduced my parents to each other. They liked each other; they were both very good-looking. Their wedding was in Sliven, probably in 1922, and my mother went there to live in my father's house. After they married, they needed money in order to renovate the factory, which my grandfather passed on to my father. My mother's dowry was very useful because with it they could buy many modern and bigger machines to make socks, which increased production. Around 60 people worked in the factory. This was how our family earned their living before World War II.

My first name is Korina. This isn't a common name in Bulgaria, but I suppose it's typical for Romania. I'm named after a cousin of my paternal grandmother who lived in Romania. She wanted to have a granddaughter, who would carry her name. I was born in 1925 in Sliven. My elder sister, Luisa, was born in 1923 and my younger sister, Soli, in 1929.

The house where I was born had three rooms and a kitchen. My grandparents and my parents had their separate rooms and we, the girls, lived in the third room. When my elder sister, Luisa, was ten years old, she went to Lovech [a small town in Northern Bulgaria] to study in the American Girl's College and she lived in a dormitory. She came home only during the holidays and slept in our room. Thus, I lived with my younger sister, Soli, most of the time. Besides those three bedrooms we also had a ground floor, where no one lived, but the living room was where we stayed during the day, listening to the radio or relaxing. In the evenings we invited our guests there.

Our family, which included seven people, prepared winter supplies every year. My father made plum jam, which was put in jars. Under the ground floor in the house, we had a large basement, where we stored supplies in the winter. We also had a maid. She helped only with the cleaning. My mother did the cooking And my elder sister, who loved cooking, also helped my mother. From the household chores, I most liked cleaning and polishing the stove.

During my childhood, while my paternal grandparents were still alive, we observed all holidays strictly and we had enjoyable times. On the Day of Atonement, on Yom Kippur, we refrained from food and went to the synagogue. On our greatest holiday, Pesach, it was obligatory to eat kosher food. [In a traditional Jewish household not only kosher but unleavened food can be eaten at Pesach.] There was a chest with special dishes on the first floor of our house, which were used only on Pesach. The ritual for the holiday was very interesting. Some time before the holiday my grandmother asked us to bring out all the dishes from the chest and put them in a cauldron with boiling water on the stove. In the middle of the cauldron, I don't know why, my grandmother put a big stone. Thus, on the holiday we used these special dishes, many of which were copper and enamel ones. Some of our everyday dishes were made of ceramics and we used them as jars. For Pesach we put a white blanket on the table and arranged it beautifully. On seder we prepared matzah, put horse-radish, fish and wine on the table. My grandfather - from whom I later inherited a very beautiful white silky tallit with dark blue and black stripes and tassels - read the Haggadah in Ladino.

In my childhood we had very interesting Purim celebrations. On that day my paternal grandmother prepared delicious sweets and dishes, which only she knew how to make. A master confectioner made sugar sticks - they were quite big and you could write someone's name on them. In line with the tradition we organized a fancy dress party and even today I make masks for my grandchildren. When I reached the age of 12, I had my bat mitzvah in the Sliven synagogue.

Grandmother spoke Ladino very well and she taught us grandchildren the language. I understand and speak Ladino. My mother, however, insisted that we learn Bulgarian very well and we spoke mainly in Bulgarian at home. My mother was very intelligent and read a lot. We had a big library at home, including many books from famous Russian authors such as Chernyshevsky 2 and Dostoevsky 3, which had been bought by my father's brothers, who were intellectuals. I loved reading- I still do - and this helped me a lot in my job. When I started studying in Sliven high school, I became interested in left-oriented publications, which were distributed illegally at that time.

Both Bulgarians and Jews lived in our neighborhood in the center of Sliven. My parents got along very well with their neighbors; they had both Bulgarian and Jewish friends. As a child I didn't notice if the other children were Bulgarians or Jews. There was no evident anti-Semitism in Sliven. Our Bulgarian neighbors weren't of the fascist type.

The Jewish community included several thousand people. There was a Jewish municipality, whose management's offices were in the Jewish school. It was a new two-story building with a big nice yard, where we played. We also had a synagogue. It had its own building, situated near our house in the Jewish neighborhood. While in Sofia the Jews had no legal right to buy houses in the center of the city after 1939 [because of the so-called Law for the Protection of the Nation] 4, which led to the forming of the Jewish neighborhood [Iuchbunar], this wasn't the case in Sliven, where relatives wanted to live closer to one another. So, there was a big Jewish neighborhood in the center. We had a rabbi and a shochet. We didn't have a special store where kosher food was sold, but we went to the shochet at the synagogue where he ritually slaughtered hens and calves.

There was a Jewish elementary school, where we studied until the 4th grade. Both Shemaya Yomtov Geron, who was also born in Sliven and later became my husband, and I studied there. Besides the main subjects, we also studied Hebrew. Unfortunately, in Sliven, Hebrew wasn't taught in the higher grades, as it was in other towns where there were Jewish associations, which supported the teaching of Hebrew. I didn't manage to learn Hebrew very well. After the Jewish school I started studying in a Bulgarian junior high school until 3rd grade and then I enrolled in the Sliven high school.

There was a big hall in the Jewish school where we organized ceremonies and celebrated the Jewish holidays. When I was a student there, at the end of every school year, we had to prepare and act out short plays. Some of our teachers prepared us very carefully for these events. We invited the whole Jewish community to watch our theatrical performance. So, the Jews in Sliven had their cultural events. They also had their organizations. My father was a member of the Bnei Brit charity organization, which raised money to give scholarships to the poorer children. The other organizations were Hashomer Hatzair 5 and Maccabi 6. They were youth organizations and all of their members were young people. I was a member of Hashomer Hatzair. The organization took us on excursions, organized lectures in which they told us about Zionism, Israel, and we also collected donations for Palestine. In some towns the [Hashomer Hatzair] organization also taught its members Hebrew, but the one in Sliven didn't. Maccabi was the sports youth organization, which organized volleyball competitions.

When I studied in high school my friends were Bulgarians, since I was the only Jew in the class. In 1942 when the repressions against the Jews started, most of my friends in the class distanced themselves from me. During those times I spent time with the Jews in the neighborhood and met secretly with the members of the UYW 7.

When I was young, we traveled very often to Sofia to visit my mother's relatives. My mother was the favorite of her parents because they wanted a girl very much and they only had boys before that. I remember the time when I was a high school student and I got appendicitis. We visited my uncle, and my mother brought me to Sofia to the clinic of Dr. Varkony, who was a Jew from Hungary. Dr. Varkony himself did the operation.

My little sister became sick at the time when the Jews were forbidden to leave their towns. This happened at the end of 1939. The doctors recommended that my sister should be treated in Sofia and we had to request permission from the police to travel to Sofia to have my sister diagnosed and treated. So we traveled by train from Sliven to Sofia.

I started feeling the repressive measures against the Jews in Sliven around 1942-43, when I was in high school. I remember that we had to wear the yellow stars and we weren't allowed to walk on all streets. We weren't allowed to be out on the streets after 8pm, and we weren't allowed to leave Sliven. At that time there were even cases of violence against Jews. There were the organizations of the Legionaries 8 and the Branniks 9, who threw stones at the Jews and at their houses.

We also experienced such violence. The bedroom where my sisters and I slept had a window facing the street. Although it had big metal bars, one night a big stone fell onto my bed, which could have killed me. That stone was thrown by the Branniks. Very often they broke our windows and yelled insults at us. I felt the restrictions against the Jews the most when I finished school. I was among the students graduating with excellent marks, but I couldn't go to the graduation ball because it took place after 8pm and Jews weren't allowed to leave their houses after this hour.

In 1943 the school year finished earlier than usual. As early as April the high school in Sliven was turned into a hospital because of the war. Also in 1943 the pro-fascist authorities confiscated my father's factory. When I found out that I couldn't continue my education in a university, my older sister and I learned to work on the machines and worked for a while in my father's factory, earning our living as workers. At that time my father's chief accountant, Madjarov, had his friends in the police department appoint him director of the factory.

The Jews in Sliven were not interned to other towns, but Jews interned from Sofia and other towns came to Sliven. My father's sister Klara with her husband and two children came from Sofia to live with us. Her family made wicker baskets and tables for a living in Sofia. They and many other Jews were made to sell whatever they could from their belongings in order to gather some money for food. They weren't allowed to work in Sliven and their life was very hard.

During World War II my father wasn't sent to a labor camp. But as early as 1940 he was interned to the village of Dabnitsa near the town of Nevrokop [today Gotse Delchev in Southwest Bulgaria]. The reason [for the internment] was that he was a Jew and a factory owner. As long as he lived there, he had to report to the municipality every evening and sign his name.

In 1944 my whole family received letters with orders to be sent to concentration camps. Even my younger sister, who was still a student, received such a letter. I remember well that the letter said that after two days we had to appear at the school carrying only the most necessary belongings because we were to be interned. But we knew very well what would happen to us. I had Bulgarian friends who listened to London Radio, sometimes I also went to their place and so I realized that we would be sent to the camps. I remember that my mother made my sister and me sew a rucksack each so that we could carry our belongings separately.

I had a chemistry teacher in high school, who was fascist oriented. She knew that I was a Jew and tested me exactly at the time when we were receiving the orders at home and we were very worried about our fate. We were horrified of what might happen to us, but the teacher deliberately tested only me so that I would feel humiliated for not knowing the lesson. I had excellent marks in all subjects; only in chemistry did I have a three. [In Bulgaria school grading ranges from six, the best mark, to two, the poorest mark.] These events took place in March. I remember well that the deportation was cancelled on 9th March 1943 and the news came to Sliven on 10th March. Later I sat for a school-leaving exam in chemistry and had an excellent mark, but I never forgot that teacher. I heard that she married a German and went to live in Germany.

My family was informed about the course of events in World War II. We knew what was happening in Poland and about the concentration camps from the foreign radio stations and from what other people were saying. We didn't consider leaving Bulgaria because my parents didn't have much money. When I finished high school in 1943, I wanted to continue with my education. I wanted to study medicine, but I wasn't allowed to. My father was willing to give me money to study in Tsarigrad, but the authorities didn't allow us Jews to leave the country. I tried to enroll in a school for midwives in Sofia, but I couldn't to do that either, because I wasn't allowed to leave Sliven. At that time it wasn't possible to leave the country in any legal way. In some towns Jews were better organized and many of them left the country, but only illegally, and moved to Palestine as early as the 1940s. I guess the Jews in Sliven weren't as well organized.

My sisters and I were more involved with the UYW than with the Jewish organizations. We became UYW members very early - while we were studying in high school. I was a student in the last grade, when I became a member. At first we helped the Sliven partisan group. We distributed leaflets against the Germans from house to house, which was very risky. Some partisans killed by the authorities were put on display in our town's square. They had come from another town and were shot without trial or sentence only because they were involved with the communists. My largest contribution as a leader of our group was saving a political prisoner from a death sentence. We gathered money and bribed the judge and so we saved the man from a sure death. We gathered food from the Jewish families when food was distributed in rations and was scarce. We put aside from the little food we had to help the political prisoners, although that was very risky. Yet, there were good people, for example a policeman who was a friend of my father and who warned him that the police was following me and knew who I was meeting with.

There were a number of secondary schools in Sliven - a girls' school, a boys' school, a textile school, a professional school for tailors. They all had UYW groups, who had their leaders. As a leader of the UYW for my high school I met with the main leader of all the schools, Atanas Sandev. Suddenly he was arrested and tortured to betray the other people from the organization. However, he was physically strong and withstood the tortures. He didn't betray me and in this way saved my life. He was sentenced and imprisoned. On 9th September 1944 10 he was released.

At the end of 1943 and the beginning of 1944 I kept in touch with the partisan squad, which was ready to accept a few more people. At that time the persecutions of Jews increased and we were thinking of joining the partisan squad and going underground. We sewed clothes and knitted socks for the partisans. Around 9th September 1944 I was an active member of the Fatherland Front 11, the UYW and later I joined the Bulgarian Communist Party.

During the Holocaust my mother's three brothers were interned to Northern Bulgaria - in Vidin and Lom. In 1948 during the Mass Aliyah 12 all my mother's brothers and their families moved to Israel.

My family didn't want to move to Israel. The main reason was that right after 9th September 1944] my father was given back the factory for a short time and he started to work. I was a member of the UYW then and had work to do in Bulgaria. What's more, I preferred to continue my education rather than move to Israel. I decided that I wanted to study medicine when I was a student in high school. I started studying medicine in October 1944. At that time my mother came down with a very serious illness - block of the biliary tree. She was on the verge of dying. The physician told me that my mother's life depended entirely on me. I had to prepare hot compresses by soaking a towel in hot water, wring it out and then put it on her liver. He said that only this heat could unblock the biliary paths. Although both of my hands got blistered by the hot water, I was absolutely determined to do all I could to help my mother get well. In this way, thanks to my efforts and determination, my mother managed to overcome the illness.

Almost at the same time as I did, in 1944, my sister Luisa started studying dentistry, but didn't graduate. During her second year she married, had a child named Mihael Alhalel and moved to Israel. After she arrived in Israel, Luisa didn't live very well. The law degree of her husband Shalom Alhalel wasn't recognized in Israel and she had to work as an egg vendor and street cleaner while her husband took the exams for law degree once again in Israel. My sister also worked as a maid in a children's home. They settled in the town of Ramla.

My sister's life was very hard. When she was pregnant with her second child, Uri, in Israel, she didn't have anyone with whom to leave her first child and she stayed at home until the very last moment. When the delivery started, there was no time to call an ambulance and they tried to transport her to the hospital in a truck. She gave birth in that truck and her husband cut the umbilical cord. Later they had a third child named Bela. During that time my sister's husband finished his university education. Their children - two boys and a girl - are now adults. One of their sons is an obstetrician in Jerusalem, the other is an engineer and their daughter is a pedagogue and high school principal. My sister has nine grandchildren, but after her husband died, she went to a home for the elderly.

My younger sister, Soli, studied pedagogy and worked as a teacher in Sofia until she retired. Her husband, Mois Semov, is a philosophy professor. He had some problems with his heart and had to undergo an operation. The doctors in Sofia, however, warned him that the operation was very risky. He had a sister who had moved to Israel. She had a good friend, who was a very good heart surgeon. After he got acquainted with the case, he offered to operate my sister's husband for free. So my sister and her husband, with almost no money, left for Israel in 1992 and after ten days Mois was operated and recovered completely. So, they remained in Israel. My sister's two twin-daughters, Nina and Mati,who are engineers and computer specialists, moved to Israel with their parents.

My husband, Shemaya Geron, and I have known each other since we were kids. Our mothers were friends and even bathed us together. Our houses were very close to each other. My husband's father had a textile shop, which was closed by the authorities at the beginning of the 1940s. In high school we got along well and went out with the same friends. My husband is also a Jew, one year older than me and studied in a higher grade. My older sister was a classmate of his. We weren't in love in high school. I was in love with a boy from the textile school, who was from Pleven. I became close with my future husband when we went to Sofia in 1944 to study at university. He studied engineering and I studied medicine. My parents lived in Sliven, while my husband's whole family moved to Sofia. I lived in a rented apartment in Sofia and visited my future husband's home to give injections to his sister. In this way our friendship grew deeper and turned into love.

In 1948 my father's factory was nationalized by the communists. They also took all our money. My father wasn't well off any more; my parents had very little money. They lived in Sliven and it was quite expensive for them to travel to Sofia. I wasn't able to help them either. At that time I had to work while studying in order to support myself. I received 100 levs a month, with which I had to pay my rent and the other expenses. My flat wasn't always heated and sometimes I had to sleep with my gloves on. My life from 1944 until 1950 was very hard. The food I ate in the university canteens was poor and never varied.

In the 1950s my father started work as a clerk in a company in Sliven, and my mother in a Jewish sewing co-operative. After I married in 1956, I invited them to live with me in Sofia because their health was poor and they needed my care.

I didn't receive aid from Joint 13 in Sliven. I remember that the Jews in Sofia received some aid in the form of blankets and clothes. I myself didn't have a new dress even at the time when I graduated from university. Then my mother sent me a well-preserved dress of hers, onto which I sewed a pink collar that my landlady gave to me. I put it on for the graduation ball at university. At that time I felt very self-conscious about my clothes.

My parents were not present at my wedding. My husband and I married in 1956, with only the registrar present, and lived with my husband's parents in Sofia. My husband's sister, Ema Geron, and her family also lived there and the apartment was quite crowded. So, after one year we went to live in an attic in the center of Sofia, which we turned into an attic apartment. We bought it with many loans and we still live in it now.

I have two sons: Yoni was born in 1957 and Mishel in 1961. My children didn't study in a Jewish school. We didn't raise them to feel Jewish in particular; we brought them up to feel cosmopolitan. My husband and I are left-oriented and believe in the socialist idea. We also raised our children in its spirit. I think that the Jewish school is crucial in raising a child to feel Jewish and my two children didn't go to a Jewish school. For example, my oldest grandson in America, who has graduated from the Jewish school in his hometown, is proud of his Jewish origins.

During the Jewish holidays, the Jewish traditions were observed by my husband's parents. We often celebrated the holidays with them. We also celebrated Fruitas 14. My mother-in-law made pouches - with different kinds of fruit and nuts in them - for my children, too because when I started to work as a doctor I was very busy. However, to this day I always light a candle on Chanukkah. When my mother- and father-in-law were no longer alive I didn't have enough time to pass the Jewish traditions on to my children. I have worked on Sabbath, because at some point in time Saturday was a working day in Bulgaria.

My husband is an electrical engineer. He worked in the State Planning Committee for quite a long time. He was dismissed at some point in the 1970s because his sister, who was a psychology professor and chairwoman of the Association of Jewish Sports Psychologists didn't return to Bulgaria after one conference abroad and went to live in Israel. Then the head of the State Planning Committee told him that he couldn't continue to work there because his sister had 'escaped' from Bulgaria. He didn't regret his dismissal because there he had much work to do. He always worked until late then and I had to look after our little children. I love my husband and after he was dismissed, I supported him and told him I would follow him even to the countryside if he found a job there. My husband started work in the Energoprojekt Institute. There he was in charge of the planning of the production of the electrical stations in Bulgaria. He retired from this job. My husband and I were very active mountaineers and often in the summers went on holiday to the Bulgarian mountains.

I finished studying in 1950, my profession is microbiology and immunology. In January 1951 I started work in the Infectious and Parasitic Diseases Institute, where I was assigned to the laboratory doing research on tetanus. Later I became head of that laboratory. I became a second degree research associate , and in 1973 I became a first degree research associate , which is equivalent to a professor's degree. From 1973 until 1990 I worked in the institute as head of the laboratory and head of the department for vaccines and prophylactics, which involved 1,500 people, working on all kinds of vaccines. I also headed the production department of the institute. In my life I am the most proud of my personal achievement in the sphere of medicine. I was the first person in Bulgaria to introduce active immunization against tetanus and whooping-cough; furthermore I discovered that old people can develop immunity against tetanus.

I could say that there was some anti-Semitism in the institute where I worked. In the 1950s when the trial against the doctors [Doctors' Plot] 15 was taking place in the Soviet Union, there was a director at our institute, who was preparing to dismiss all doctors of Jewish origin working in the institute. Four Jews worked in the institute and the director said that he would fire us for our inefficiency at work. But the real situation was quite the opposite, because each of us had accomplished achievements in the research area. I myself was awarded for my contribution to the research work in the institute only three months before the director decided to dismiss us. Then we decided to file a complaint at the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party. They called the director and made him cancel his plan.

Before I became a first degree research associate , I defended my dissertation and wrote a doctorate. My husband was very understanding. Once, when I had to develop a new method for identifying the antibodies in human blood, I had to go to the institute and examine the mice on which I experimented. Although my husband was very tired, he didn't hesitate at all, but accompanied me. He was ready to do anything to help me continue with my research activities. When I had to write my dissertation, he did all the household chores so that I would have enough time.

It so happened that two Jewish women, a colleague of mine and I, were applying for the professor's degree. At that time the director of the institute had changed - now it was Prof. Shindarov. He was a kind and honest man. He had completed his education in the Soviet Union and he was a distinguished scholar. We were close and I asked him if he wasn't worried about proposing two professorships for Jewish doctors at the academic council. He told me that he was doing the right thing and the two of us deserved our professor's degrees. Our reviews were absolutely positive, at that time the reviews were made by three professors. Thus, there were no objections and we became first degree research associates.

There were people in the institute who were very good specialists in their areas. For example, I reviewed the whole world literature on the issue of vaccines against tetanus. I myself translated articles in French, German, Italian, English, Spanish and Russian. With some help, I also used Japanese and I was very proud that the Japanese researches had also written about me and my discovery that old people can develop immunity against tetanus. On the whole, in order to advance in my career, I had to rely completely on my own skills. The fact that I was a member of the Bulgarian Communist Party didn't help me at all and I always fought for everything. [During the communist regime in Bulgaria members of the Bulgarian Communist Party were often treated in a privileged way ]. Now I'm a member of the Bulgarian Socialist Party.

From 1948 until 1963 I didn't see my sister Luisa at all. I wanted very much to go and see her, but the police didn't allow us meet her - neither my mother, nor me. In the summer of 1963, before I left for Israel, I had an interesting experience at the institute. During a meeting at which more than 30 people were present, doctors, chemists and pharmacists, I requested to have my whole annual leave amount of 40 days. Then the head of the institute answered that production was increasing and there was a lot of work to be done. He asked me why I was requesting such a long leave. I answered in front of everybody that I had a sister living abroad, whom I hadn't seen for more than ten years. This separation was very painful for me since I had absolutely no news from her. My colleagues at the institute weren't ill disposed towards me. In the end, I was granted the requested leave and my husband and I traveled to Israel to visit my older sister Luisa. Our son remained in Sofia at my parent's place.

During the wars in Israel in 1967 [Six-Day-War] 16 and 1973 [Yom Kippur War] 17 I was also very worried about my sister and her family. I think that during those wars Bulgaria was not firmly against Israel. I remember that my colleagues at the institute encouraged me not to believe the news we heard about the war.

My son Yoni graduated as an engineer and is a specialist in radio and television equipment. He worked in an institute and there he became a research associate. Afterwards he married a Jew named Ameliya Bidgerano. They had a son, Vitaly, who is now a university student in the US. Yoni went to Hungary where his wife, who was a doctor, was preparing her dissertation. My son had a good job in Bulgaria, but he was ready to work anything, only to be with his wife. After his wife finished her dissertation, she took part in a conference of young scholars in London and there she met a doctor from America, who offered her a job in the US. She agreed and my son's whole family left for the US in 1991. But things went bad there. Less than a year after they left, my son's wife died in a tragic accident during an excursion.

Yoni remained to live with his child in Minneapolis. He was invited by the professor, with whom his wife worked, to work as a laboratory technician. In this way, he found a job and decided to stay in the US and look after his son by himself. Four years after the death of his wife, my son met another woman, who is also a Jew. Her name is Lora. They liked each other and got married. His new wife is involved in charity activities. My son has two children from his new marriage - a boy and a girl. Their names are Noah, who was born in 1998 and Eliyana, who was born in 2001.

In 1994 my husband and I visited our son in the US for the first time. We went for three months to look after our grandson. In Minneapolis summers are very hot and winters very cold. When I was in America, I was impressed to see people put small statues in their yards at Christmas time, picturing, for example, the birth of Christ or the Virgin Mary.

My other son, Mishel, has been in love with photography ever since high school and decided to pursue it as a profession. After he did his military service, he applied to the College of Photography in Sofia and became a professional photographer. Now he works as a photojournalist for the Noshten Troud newspaper [an evening weekly focusing on nightlife and crime]. He is married to a Jew, whose name is Jana,nee Kohen, and has two boys - Emil, who is eight years old and Mihail, who is seven years old. His wife graduated from the School of Economics and works in the Statistical Center.

I think that the opening up of the Eastern European countries to the West is very useful. I only wish that the economic situation of Bulgaria were better. I retired with a relatively big pension in 1990. I worked in the institute for 40 years: I started work there as a young doctor and left as a professor when I retired at 66 years of age. After the inflation, after 1990, my pension decreased drastically. Life became harder. The retired intellectuals in Bulgaria are at a very disadvantaged position. All retired people in the West live a better life. I know that they can even afford some charity donations with their saved money. My pension is such that I cannot afford to travel where I want to. A colleague of mine, a retired doctor living in Austria, has enough income to give some aid to the poor families living in the Vienna suburbs each month. What's more, he invites guests from abroad for a long time entirely at his own expense. I cannot afford to invite a guest even to a restaurant.

I have many acquaintances abroad, since I have traveled many times before to take part in conferences, and the situation here depresses me. It humiliates you, making you unable to help your children. I have always loved Bulgaria; I have always liked it. Years ago, my husband and I had opportunities to travel abroad. I have visited many countries in Western Europe - Spain, England, Germany, Hungary, Poland. I have been there for conferences and I went on excursions.

Glossary