Janos Dorogi

Budapest

Hungary

February 2001

My family background

My father’s mother was called Berta Schwartz. She was born in Kecskemet around 1860. She went to grade-school there. She finished 6 grades. First she lived in Nagyvarad [now Oradea, Romania] then in Marosvasarhely [now Tirgu Mures, Romania]. She went there with my grandfather because that’s where one of my grandfather’s cousins – Vilmos Feiglbaum – lived. He had the biggest colonial goods trade in Transylvania, and he had no children. And he wanted to leave the business to my father. In the end he closed the business and bought a little one-floor house, and my grandmother, who was a widow by then, went there to take care of her beloved in-law, who was blind.

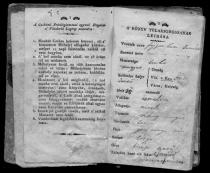

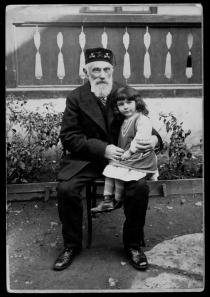

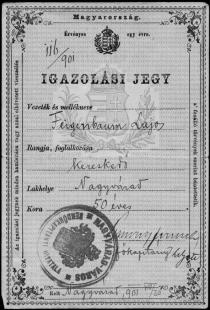

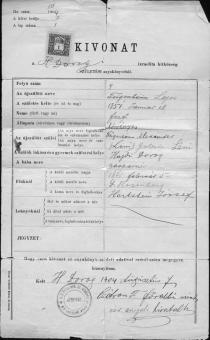

My grandfather [Lajos Feigelbaum] was born in Hajdudorog. Then he had a little tool workshop in Nagyvarad. He put together one of the first bicycles in Hungary there. He also installed the first telephone in Nagyvarad, in the Town Hall. My grandfather wasn’t well-to-do. I’ve got a couple of cards from the front that he wrote my father when he sent him 50 crowns, ’send it back, because I’ve got such troubles’. My grandparents actually kept kosher. But my grandmother didn’t wear a wig.

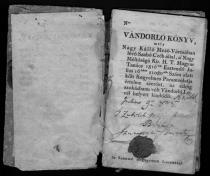

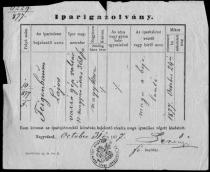

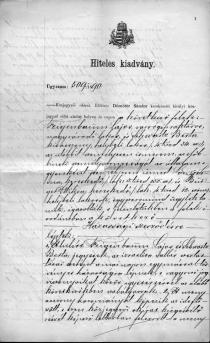

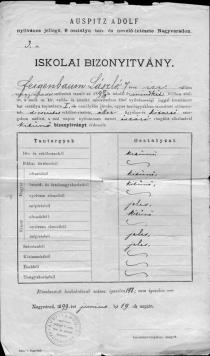

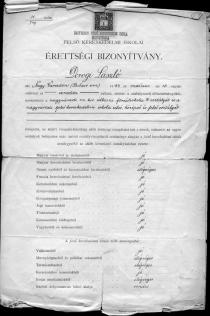

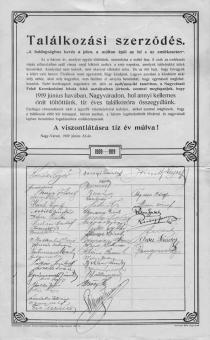

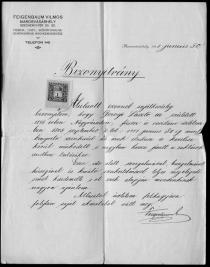

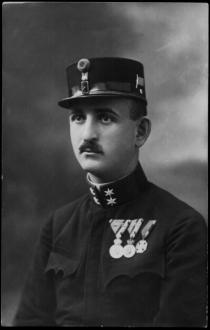

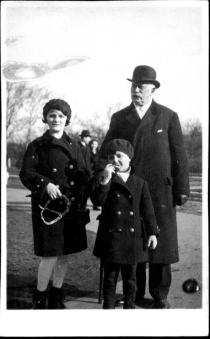

My father was born in 1893 in Nagyvarad. He was called Laszlo Feigelbaum, but he magyarized it to Dorogi in 1906. My grandfather decided to magyarize it, and it became Dorogi because he was born in Hajdudorog. My father went to high-school for four years in Nagyvarad, and then to a trade college for three years. He graduated from there. Uncle Vilmos, who wanted my father to work in the trade business, sent him to Pest for a year to learn banking, and in Marosvasarhely he sent him to work with an agent who would buy a trainload of, say, coffee or tea for the business. Uncle Vilmos had my father educated. But in the meantime the war began. My father was a volunteer then, with the rank of Captain. He was sent to the Russian front, and he got shot so badly in the arm in ’17 that his right arm was paralyzed.

That’s why I didn’t wear a star, and in ’44 I got into the university, where I wrote that my religion was Israelite, but I was not to be considered a Jew. Right after the war my father got into the Association of War Invalids, and worked there for two years. At the start of the ’20s the Rico Bandage Factory was established. My father became the Assistant Director there. Then in ’28 he got into the Hungaria Rubber Factory, which had ten workers at the time. By the time of the Second World War it had 1,200 workers, and was a very modern factory. And my father was there until December 2, 1944. When the Germans came in, I also joined the factory right away. It was a first-class military-factory, and that’s why I came back out of forced labor, because I got a special relief, because the factory director said that Dorogi had done more for the Hungarian homeland than anybody else.

My father went to temple regularly. We went to the boys’ orphan home, where there was a nice, modern synagogue, with an organ. And the service always started with a schnoder of 50 thousand golden Pengos. My father always gave them 200 pairs of gym shoes because he said ’you’ll steal it otherwise’. And my father was proud to admit he was a Jew. Along with the fact that he was a K. und K. soldier, with medals.

My father had only one sibling, a little sister called Ilonka. She married Zsigmond Brechel, the son of a very well-to-do family from Beszterce [now Bistrica, Romania]. That was a patriarchal Jewish family in Beszterce. They had a brewery called Hohrich and Brecher. They made a quality of beer that was very well known in Transylvania.

There was a brass mesusah on every door in the brewery. Uncle Zsigmond worked in banking, and for awhile he was the Director of the Romanian-Hungarian Bank in Kolozsvar [now Cluj, Romania], and then Arad. Then the bank somehow didn’t do too well, and the family asked Uncle Zsigmond, who understood banking, but didn’t like to work, to run the brewery. When the Jewish laws were passed, Count Balazs Bethlen took on the brewery as a strohman [false director, or frontman]. Then they deported the family. They would have saved my uncle. Mengele told him to step a bit to the left, but after a little thought he went over to my aunt. He was murdered immediately….the first day. In Auschwitz. They had a daughter, Eva, who was also killed, but there’s no way to tell where.

My great-grandfather was called Steiner. He must have been born around 1840-1850. He had a sort of guesthouse in Gyongyos. He died relatively young. He had 7 or 8 kids, both boys and girls. If I look at his picture, I had a really ‘gutmuttig’, dear, and very handsome grandfather. He wasn’t deeply religious. He had a true Jewish family, full of love. But the rest of the siblings, the kids all married Jews. He wasn’t a Neolog in the sense of today – he surely kept the great holidays. I don’t believe the house was kosher. Well, the guesthouse wasn’t kosher for that matter. One of his sons took over the guesthouse. He was nice and a great singer.

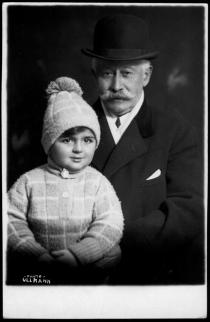

My mother’s family, the Ullmanns, also came from Hajdudorog. My Ullmann grandparents had six children. My mother’s oldest sister was Ilus, then came Iren, then my mother, Margit, she came in ’94, then Jolan in ’97, Marcsa in 1902, and after her Sanyi [nickname for the male Sandor]. My aunts all resembled one-another, in appearance and character too. Since he [the grandfather] had six kids he wasn’t drafted to be a soldier, but worked for the Red Cross. For instance, he was there to meet the trains coming from the front in the First World War. My grandfather was a very good-looking man. He wore a top-hat and it was always a joy to walk with him on Andrassy Road [in Pest] because we lived nearby. Grandpa Ullmann prayed in the morning. He didn’t go to temple much, but he prayed, every morning.

Aunt Berta was one of my mother’s youngest aunts. She was very smart, and cross-eyed, and one of the ugliest of the girls, and she married a man named Richard Igel. Uncle Igel was a wiry-haired, bandy-legged Jewish man. He never did know Hungarian well. He was from Moravia, and was the son of a very well-to-do family. My mother’s family got to know his mother, and his five sisters who were elegant ladies. They were well-to-do Moravian Jews. Richard Igel didn’t really want to study, and he zipped in to be a soldier in the Monarchy. He was a gear-making sergeant, and he’d make horse tack, saddles, and horse outfits. And when he got married, and took aunt Berta, they opened a saddlery in Gyongyos that became famous all over the country. The aristocracy there had their coach gear, and horse fittings done there. I got a rocking horse from him when I was 3 or 5 years old, and it was covered with real hide. Aunt Berta would come up and visit Pest from time to time, to see my mothers’ family. Then she was really devastated because her sole daughter, Bozsi, married a non-Jew from there, Sandor Benei. Those Beneis were very well-to-do peasants. And their boy, who wasn’t prejudiced against her because she was a Jew, fell in love with her, and Bozsi married him, and they had a child.

My mother had one other aunt, Etel, whose husband was Gyula Weinberger. When they circumcised me he was the one who held me. Uncle Gyula was started as an apprentice with Lampert-Wodianer Press, which later became Franklin Publishing, and was a real powerhouse, and he became the Director whom everyone respected enormously. My childhood is wound-up with uncle Gyula. Uncle Gyula was good-looking. We would have our summer vacations in Nogradveroce, and sometimes we’d go to Vac or Nagymaros by boat to the market. And then early in the morning the boat was full of saleswomen, and baskets, and everything. Uncle Gyula would immediately stand up, if he was sitting, and have an old peasant woman sit down, and he would say – he was relatively old then – ‘my dear soul, I’m only on summer vacation, you’re tired, please take a seat’. Everybody really liked that. Uncle Gyula died in ’41 or ’42.

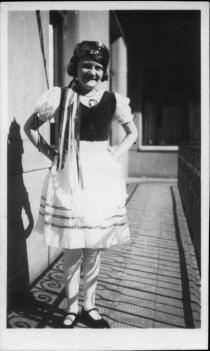

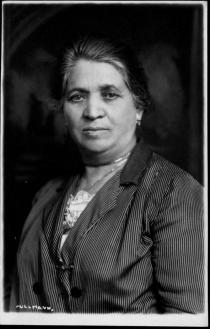

My mother was a beautiful woman. She was truly beautiful. She was a closed and reserved, but also unusually pleasant and delicate. She and her siblings were born in Pest. They lived in Rozsa Street, and they went to school there where the Basilica is. They only went to Gyongyos to visit their grandparents. But they always spent their childhood summers there. During those visits they learned all sorts of dirty poems, and phrases from peasant children, and the local dialect. My mother finished trade school, but just a one-year course, and before that she attended grade-school like her siblings too. My aunt Iren and my mother started to work, because they needed to. Both of them wrote beautifully, expressively, and could take shorthand. My mother got into the National Manufacturers’ Alliance, before the First World War, because she wrote so well and beautifully. And she worked there until it was closed, until ’47 or ’48.

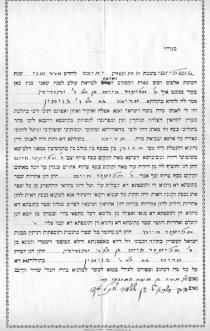

My mother got a prayer-book from my father once, who courted her back in ‘20. In it he wrote, ‘believe and trust in this book, so that every one of your desires may be fulfilled. Laci’. It was the famous, beautiful prayer-book by Arnold Kis. Just in Hungarian. Because my mother was completely amhorets [ignorant] from that point of view. When my parents got married, they were to have the Rabbi, Dr. Simon Hevesi marry them [He was the Chief Rabbi of Budapest from 1905 – one of the leading figures in Jewish social and cultural life at the time.] But he suddenly got sick and asked, ‘what would you say if my son, who just became a rabbi, were to marry you, it would be his first independent marriage.’ My father said, fine. And the famous Bernat Linevszki was the main cantor.

Growing up

My parents lived in Dohany street, but in ’26 my father was sort of out of a job, and we had to give up the flat. That’s when we moved to where my aunts lived. So, my grandfather Ullmann, my mother’s three siblings, my mother, my father and I lived in that very big apartment [Janos was born in 1924]. I grew up there from ’26 to 1933. Then, in ’33, when my father had become a good, honored colleague, his pay was 1,000 Pengos, and that was quite a good salary then. Summer vacation, and everything else we needed, fit in.

I started school in Sziv street, because it was the standard then that there should be no private school. My father wanted me to go to the Lutheran high-school in the [Varosliget Avenue], because he had good information, and it came through too. But they told my father that they would put me on the list, and I could only go if they had a place. So my father, the moment that happened, grabbed me and had me entered in the Avenue [i.e. this Lutheran high-school]. I got into high-school, in the year the Numerus Clausus came out, so there could only be 10% Jews in any class. I went to religious school there from first to eighth grade.

The Levente training [a quasi-fascist troop, modeled on the Boy Scouts] started at the end of the ‘30s in that school, just about the same time as the first Jewish law. It was required. I wasn’t really a Boy Scout, just a little bit, in one of those Jewish Boy Scout troops. During Levente class the Leventes would practice in hats and with rifles. The Jews, depending on the school, had to practice with shovels. In the Avenue, when they told us ‘specially to get shovels, I went into the principal and asked why. The principal was very kind to me because he respected my father, who was a decorated officer. He was just a lieutenant. And he said, if I need a shovel the school would buy one for me. What a shame that brings to the spirit of the Avenue school.

We had summer vacation in Nogradveroce every year. My parents went on vacation there for the first time in ’24, and they went there until my father’s death. My parents went on vacation there for 24 summers, and I spent 20 summers there. We always took the whole household with us, because that was the style. With the servants. From the end of May to the first of October. The Hungaria Rubber Factory gave us their car – it was a dark green, closed, large coupe, with big back doors – there were our baskets, our chests, the whole household went. And we always rented there. Those who were a good deal more well-to-do had their own villas. The aunts were always there for the summer at Nogradveroce too. Pretty much the same company had vacation together, it got to be a big circle of friends. Jews. Mostly Jews. My father always went in to work in the morning, and came back at noon.

My father, who really knew how to lead a Seder, never hosted one at our home. My aunts weren’t really interested in religion. My aunt Iren was rather an atheist. Friday they kept, my mother lit candles. But my father bought a gorgeous, leather-bound complete prayer book – unfortunately somehow we managed to spirit it away. There were one or two volumes on Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. My father bought them. He took me, when I was still a little kid, to temple, then in school it was sort of required.

Well, let me tell you about my Bar Mitzvah we had in ’39. It was in the boys’ orphanage in elegant surroundings. It was important for them that I do it there. When there was a Bar Mitzvah then everyone who was to be invited got a very nice, proper invitation. Jews and non-Jews. The circle of friends, the immediate ones, wasn’t all Jews. But they all know that he went to Rosh Hashanah, or temple. He didn’t go regularly, sometimes on Friday, but usually I did instead, because its what you half-way had to do in school. At the end of ’44 I fell out with the non-existing God, I even went so far as to say that man made God in his likeness, and not the other way around.

After the war

I finished medical school in ’49, and by ‘50 I was working in the hospital in Kutvolgy as an internist. First I worked as an internist, and then as a pediatric surgeon. I met my wife at the university, when I held a contest as a graduate student, and where my wife was the best of course. We got married in December of ‘50. Unfortunately my father didn’t live to see it, but I thank my lucky stars that he at least got to know Agi. My mother and her two sisters lived with us right away, and Agi had to give up a lot for them, but I believe we got along well with my aunts and my mother until they died. It could be that’s why we never had any children, and why we traveled so much, and travel so much now. Even though my wife’s family, who were as Jewish as we were, had Christmas, because one of her aunts married a Swabian, the two of us never celebrated Christmas, but we didn't celebrate Jewish holidays either. (My mother had a little prayer-book, though, and I know she went to the synagogue from time to time.) It’s hard to say, but we only felt comfortable among Jews, even though we were mostly surrounded by non-Jews at work, naturally.