Irina Herman

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of the interview: September 2003

Irina Herman looks young and beautiful. She lives in a three-bedroom apartment in a new district in Ternopol. Irina is slender, but she looks ill: she had a severe surgery recently. However, she keeps her apartment very clean and cozy. She has plain furniture in her apartment. There are embroidered pictures on the walls and embroidered covers on the sofa and beds that the hostess made herself. Besides flowered and fold patterns there are portraits of Taras Shevchenko 1, Sholem Aleichem 2, and … a rabbi. Irina speaks fluent Ukrainian and I conducted this interview with her in Ukrainian.

My mother’s parents, my grandfather Leizer and grandmother Esfir, died long before I was born and I didn’t know them. My grandfather’s last name was Nepomniashchiy, but I don’t remember my grandmother’s maiden name. They were born approximately in the 1860s in Tomashpol, Vinnitsa province, 250 kilometers from Kiev, where they lived their life.

Tomashpol was like any other Jewish town within the Pale of Settlement 3. There was a market square in the center of the town. Sunday was a market day. Ukrainian farmers from surrounding villages came to sell their products at the market. They also did shopping in local Jewish shops buying haberdashery, fabrics and shoes. There was a sugar refinery and a milk factory where workers were local Jews and Ukrainians from surrounding villages.

There was also a small fabric factory in the town. It belonged to my grandmother’s relatives. There were few richer Jewish houses belonging to the doctor, notary and attorney. Jews mainly dealt in crafts. They were shoemakers, glasscutters, carpenters, tailors, etc.

There was big and beautiful synagogue in the center of the town. It operated until the middle of the 1930s when the Soviet regime began to ruthlessly destroy everything religious 4 and the synagogue was closed. Jews went to pray in a prayer house.

There was a nice lake in the village from where a little river started flowing. Local Jews often bathed in this river and lake on Friday before Pesach. After bathing they put on clean clothes.

My grandfather Leizer was a craftsman, but I don’t know exactly what he was doing. He finished cheder, could read the Torah and Talmud and knew prayers. My grandmother Esfir had no education. She knew prayers by heart since her childhood. Theirs was a poor family living from hand to mouth.

It was common for Jewish women to be housewives after getting married, but the family was so miserably poor that my grandmother Esfir had to go to work. She worked as a yarn winder at the fabric factory.

The family owned a small house that almost rooted itself into the ground. There were two little rooms, a kitchen and a big Russian stove 5 in it, and a fore room in the house.

My grandmother and grandfather were religious. They followed the kashrut and strictly observed all other traditions. It was easy to follow the kashrut in their family since they hardly ever had meat. They saved to buy a chicken before a big Jewish holiday to keep it in their fore room till the holiday time. They mainly ate bread, potatoes and beans.

On Friday they did a general cleanup of the house. They scrubbed utensils and washed the floors to be prepared for Sabbath. My grandmother lit candles and grandfather recited a prayer. They followed all the rules. On Saturday my grandmother and grandfather went to the synagogue. They raised their children religious. My grandmother and grandfather died in the early 1930s and all I know about them is what my mother and relatives told me.

According to my mother there were thirteen children born in the family. Most of them died in infancy from diseases. Only five children, including my mother, survived. My mother’s two older sisters moved to America in the early 1900s and there was no further contact with them. I don’t know their names. I only knew my mother’s sister Leya and brother Moishe.

The children didn’t get any education. They had to go to work at an early age. My mother’s sister Leya, born in 1898, went to work at the factory where my grandmother worked. She became a winder. She married a wealthy Jew when she was very young. He was a tailor named Gershl Spector. My grandmother tried to take advantage at least of the fact that her children were beautiful and she thought that Leya’s marriage was a very nice arrangement. Leya had a good life with her husband. They had a big two-storied house with a number of rooms and good furniture. There were housemaids in the house.

Leya had another baby every year. She had seven children. Her older daughter Sarra, sons Fishel and Boris were in the army during the Great Patriotic War 6. Fishel and Boris perished. Sarra married her fellow comrade/soldier. He is Armenian and they live in the Northern Caucasus now. Leya’s middle son Haim lives in Moscow and the youngest Etia died in Tomashpol recently. Two other children perished in the ghetto in Tomashpol where Leya and her younger children were during the war. Leya died in Vinnitsa in 1952.

My mother’s brother Moishe, who was about two years older than my mother, married a wealthy woman for money. His wife Shura was so ugly and Moishe could never forget that he was forced into his marriage. Moishe was a laborer.

His son Lezha and daughter Ida had higher education. Lezha and his family live in Moscow. Ida married a Jewish engineer from Vinnitsa. His name was Arenson. They lived in Vinnitsa and only left it during the war.

Ida died of cancer in the middle of the 1960s. Moishe and Shura had another son named Bulia. He was deaf and mute, but he was a very handsome, smart and kind guy. Shortly after the war he got lost in a forest searching for wood. He froze to death. They found him a few days later. Moishe was at the front during the Great Patriotic War. After the war he returned to Tomashpol. He died some time in 1984.

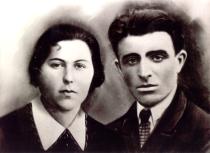

My mother, Hova Herman, nee Nepomniashchaya, was born in 1907. She was the thirteenth child in the family. My mother had no education whatsoever. She spoke Yiddish and Ukrainian like any other resident of Tomashpol. She knew prayers by heart and prayed all her life. She went to work at the factory at the age of approximately 13.

My mother was a reserved person. Perhaps, it resulted from her lack of education. Anyway, she never told me about her young years or how she met my father. All she said was that she married for great love which was not the case with her sister Leya and brother Moishe. My other relatives told me some details of her meeting and marrying my father.

My father’s parents, Perl and Bencion Herman, were against my father’s marrying my mother. They were wealthy and didn’t want their son to marry a poor girl. Perl and Bencion were of the same age, they were born in 1886 in the village of Alexandrovka, 25 kilometers from Tomashpol. There were three or four Jewish families in this Ukrainian village.

My grandfather Bencion’s brother lived in a village across the river. I don’t remember his name. I remember his daughters’ names: Etia, Haya and Esia. They often came to see their father.

Grandfather Bencion had education. He had Jewish education, could read and write in Ukrainian and even Russian. He was a postman in his village for many years and his fellow villagers respected and loved him.

Grandmother Perl had little education. I have a towel that her mother, my great-grandmother, embroidered for her wedding. I’ve always kept this wedding towel and even the colors on it haven’t faded. There is ‘To dear bridegroom and bride, good evening, all!’ embroidered on it.

Perl was a very active person. She took care of her big household. There was an orchard around the house and a vegetable garden where they grew vegetables for the family and for sale. Perl also kept poultry and cattle: cows and pigs. The family supported its well-being working tirelessly, but during the period of famine in 1932-33 7 authorities took away almost all their bread and food stocks and Perl, the only one of the family, starved to death. So I never met this grandmother.

My father’s parents were religious Jews. Grandfather Bencion was particularly religious. There was no synagogue in Alexandrovka and Jews from Alexandrovka and a neighboring village got together in one house to pray. My grandmother Perl was so busy about the house that she hardly had any time left for religion and prayers.

Perl and Bencion had three children including my father: two sons and a daughter. A visiting melamed taught the sons. Vol’ko, the older son, was born in 1906. Vol’ko became an apprentice of a local carpenter. After finishing his training he became a skilled cabinetmaker. After the revolution 8 he moved to Leningrad where he finished a technical school and then he taught the carpenter craft in a vocational school.

During the Great Patriotic War he, his wife Raya and their small children Naum and Boris were in evacuation in Novosibirsk. Vol’ko gave up religion living in this big town. He didn’t pray, but he celebrated Jewish holidays as tribute to traditions. After the war their family returned to Leningrad. Vol’ko died in the middle of the 1970s. Naum lives in St. Petersburg and Boris and his family and his mother Raya live in Israel.

My father’s sister Rieva was born in 1910. Rieva had good education. After finishing a seven-year school she finished a Soviet Trade School and then a Trade College. Rieva was a member of the Communist Party and worked in the regional party committee in Vinnitsa. She married Samuel Rachelgauz, a Jew, who was a military, in 1939, and followed him to wherever he had to go on his military service across the country. They lived in the Far East and Siberia and when Samuel retired they returned to Vinnitsa.

Rieva and Samuel had three sons. All of them had higher education. They were very talented and became respectable members of society and skilled experts in their fields. Roman, the oldest one, born in late 1940 finished a Ship Building College. He became a doctor of science 9 and lives in the USA now.

Boris, the middle son, finished a Polytechnic College. He lives with his family in Voronezh, Russia. The youngest named Yevgeni finished the Moscow College of Physics and Mathematics. He was director of a plant. Now he lives in Moscow.

Rieva died in Vinnitsa in 1997. Her husband lived another year.

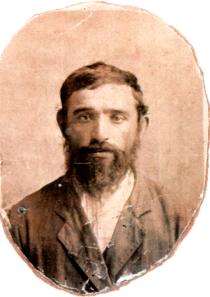

My father, Shmuel Herman, was born in 1907. Although he only had primary education and was deeply religious, most of his friends were Ukrainians from a neighboring village. Actually, he was like a Ukrainian guy himself being tall and stately. Many girls wanted to marry him: he was handsome and hardworking and came from a wealthy family.

I don’t know how my parents met, but they fell in love with each other for the rest of their life. This happened in 1927. My mother had typhus and my father, who wasn’t even her fiancé at the time, nursed her to recovery. She was thin and her hair was shaved, but he took her to his home to introduce her to his parents.

My grandmother Perl was horrified: besides being poor she was a plain and sickly looking girl. She didn’t give her consent to their marriage. She intended to find a rich fiancée for her son and took him on her sledge to another village where matchmakers found a match for my father.

The family legend says that the horses got stubborn at some distance from the village – and this was happening in a severe winter with a lot of snow – and Perl couldn’t make them move another step however hard she tried. She had to go back to Alexandrovka with my father and give her consent to their marriage.

They had a traditional Jewish wedding in summer 1928. The bride and bridegroom stepped under the chuppah at the synagogue in Tomashpol and then rode back to Alexandrovka where they had a wedding party with all relatives and fellow villagers present.

After the wedding the newlyweds settled down with my father’s parents. My mother was smart and hardworking and began to help Perl about the house. Soon my grandmother liked her as if she had been her daughter. My father started construction of their house, but during the period of famine in 1932 this unfinished house was disassembled for wood.

My father went to his older brother in Leningrad hoping to earn a little. He brought a bag of dried bread from there. There was a surprise waiting for him at home: my mother gave birth to their first baby after three years of marriage. The baby was named Lev after her deceased father: the first letters in the name of my older brother and my mother’s father are the same.

In 1933 Perl died of hunger and my grandfather married my mother’s cousin sister Rosa who was much younger than my grandfather. Rosa became the hostess of my grandfather’s house in Alexandrovka.

My parents didn’t get along with my father’s stepmother and moved to the house where my mother had grown up in Tomashpol. The house was empty after my mother’s parents died. In 1936 my sister Polina was born in this house. She was named after my grandmother Perl: their names sound alike. In 1937 I was born there. I was named Fira after my mother’s mother Esfir. Later they began to call me Irina. It’s a Ukrainian name and it is written in my passport.

I remember our house dimly: it was a small house rooted into the ground. There was a fore room, two small rooms and a kitchen with a Russian stove. My mother was used to living in a village. She kept a cow and poultry in the shed in the backyard of the house. We had a good life before the war. My father was a worker at the sugar refinery and my mother was a housewife.

Every Friday my mother cleaned the house, washed the floors and prepared for Sabbath. She left our Saturday meal in the oven and we sat at the table after we came from the synagogue on Saturday. I have vague memories about this time, but I remember that waiting for Saturday was festive.

I also remember Pesach when matzah was baked for the holiday and my brother and I made holes in matzah rolls. There was no synagogue in Tomashpol and all Jewish families made matzah at home.

I have dim memories about other holidays as well. I didn’t know their names, but I remember triangle pies with poppy seeds that my mother made for Purim, potato pancakes and doughnuts at Chanukkah. I remember that my parents fasted at Yom Kippur. My mother fasted the rest of her life, but our parents didn’t make us, children, fast. This was during the Soviet regime when authorities didn’t approve of religion. Our parents probably wanted to bring no complications into our life.

In 1940 my father was recruited to the army during the Finnish War 10. He returned home soon: he had lost his arm. From then on he worked as a janitor at a plant and spent much time at home helping my mother about the house and spending time with us, his children whom he loved dearly.

Our family often rented a horse-drawn wagon to visit Grandfather Bencion in Alexandrovka. He and Rosa had a son one year older than me. His name was Moishe. We were friends. We bathed in the river and played with a ball in the yard. My grandfather told us stories. They were probably chapters from the Torah, but I don’t remember what they were about. All I remember is how we sat there listening to him.

We spent summers in Alexandrovka. We were there when the Great Patriotic War began. I don’t remember how it began. We didn’t even have time to consider evacuation – two weeks after the war began German troops came into the village.

My first bright memory refers to this time. It is probably imprinted in my memory for the rest of my life, this horror that I felt. Two days after the Germans came to the village I was playing in my grandfather’s yard. I don’t know where my parents, my brother and sister were. A half-drunk German soldier came to the yard. He began to pester my grandfather ‘Judas, Judas, give me chicken, eggs and milk’ pulling grandfather by his beard and threatening him with a gun.

My grandfather started walking toward the cellar with this German following him, when all of a sudden my grandfather jumped to me, grabbed me and jumped into the well holding the rope. We were lucky that it was a hot summer and there wasn’t much water in the well. We could hear the German cursing and shooting.

When it became quiet our Ukrainian neighbors pulled us out of the well. My mother and sister came. Although nobody thought it was a threatening incident our Ukrainian neighbors gave us shelter on the attic in their house: my mother and sister and I were hiding there.

We didn’t know where my father, grandfather and brother were. A few days later my father came. He said that he and grandfather found shelter with our Ukrainian neighbor Zenyunka.

Zenyunka actually saved my brother. When the Germans met him they called him ‘Judas’ and told him to put down his pants to check whether he was circumcised when my grandfather’s quiet neighbor Zenyunka ran out of her house, grabbed my brother and said that he was her son and had nothing in common with Jews. My brother’s Ukrainian friends had taught him a Christian prayer ‘Our Father…’ and he recited it in Ukrainian and the Germans left him alone.

My father and grandfather decided to leave the village. They understood that the Germans were not giving up. Tomashpol was still under Soviet rule and my father decided to go home to Tomashpol. Our family and my grandfather and Rosa and Moishe and our Jewish neighbors were there and we decided to move across the woods. We covered the distance to Tomashpol of 25 kilometers in three days since we could only move at night.

When we came to the town there was actually anarchy there. We went to my mother’s sister Leya. She was baking bread and we were so starved that we pounced on a loaf of bread. It was fresh and smelled delicious.

Our neighbors and relatives came to see us. They didn’t believe what my father and grandfather told them about their victimizing Jews. They thought that the Germans were just frolic. Old people remembered World War I when Germans had a respectful attitude toward Jews and didn’t think they could do any harm. Many of them laughed that my father dug a shelter underneath our house to hide from the Germans. He dropped rags on the floor so that nobody could suspect an underground shelter. This shelter served us well during the occupation.

German troops came to Tomashpol shortly afterward. On 4th August the first terrifying operation against Jews was conducted. On that morning my father and grandfather went to pray in the prayer house as usual. My mother, my sister, I and my aunt Rosa and her son were waiting for them at breakfast. At that moment a raid began: Germans were coming to Jewish homes chasing Jews out of their homes with whips. Some managed to hide. My mother’s sister Leya hid in her basement.

We were taken to the square where Germans read an order issued by German commandment ordering us to go to work under the fear of death. They didn’t allow us to take anything with us. We were told to line up in a column and march across the town. There were guards with dogs on the sides. Nobody thought that this was a death march.

At that time we saw another column marching along the adjunct street. There were men from the prayer house in this march and we saw my father and grandfather. My father rushed to our column, but of course, he was forced to go back. This was the last time I saw my father.

My brother hit his foot and began to cry, but my mother begged him to move on. She was afraid that they would kill us if we didn’t keep the pace. At that time a German guard noticed us. He called us to come closer and told us to go home speaking German. I still don’t know why he did this. Perhaps, he liked my mother or we reminded him of his children in Germany. He ordered a policeman to take us home. My brother ran after the column where my father was.

My mother and I went back home. My mother started cooking dinner. She was waiting for my father and grandfather to come back home. She thought they were working somewhere. Time passed, but nobody returned. In the evening we heard shooting at a distance. There were wounded people with blood on them making their way home across the gardens.

My brother came in the evening. He told us that he followed the column for a long time until my father told him to go back home. He hid in a forest and saw fascists killing Jews, but he didn’t see my father or grandfather among those who were killed.

Later Ukrainian witnesses told us that the column covered about 20 kilometers almost as far as Yampol. On the hill where an old Jewish cemetery was located Germans gave prisoners spades and ordered them to dig graves. Somebody screamed that they had to run for their life. My grandfather Bencion was among the first ones who tried to escape. A fascist ran after him and cut his body in halves with a spade. My grandfather was thrown into a ravine and then they threw there other Jews who were still alive.

A policeman, our fellow villager from Alexandrovka, who often visited us before the war, ran after my father. My father egged him to let him go and have mercy on his children, but this policeman beat him hard and then threw him into the ravine. He was still alive. People were saying that the earth was breathing for a long time afterward: there were many buried alive, including my beloved father.

After this horrible day my mother kept us in our shelter. She only went out to get some food. She took our cow to our Ukrainian acquaintance in Alexandrovka hoping that she would help us when we were in need.

About two weeks later I fell ill with scarlet fever. There were no medications available. My mother carried me to an infectious diseases hospital in Komargorod, about 15 kilometers from Tomashpol. Doctor Drozdovski, either Polish or Ukrainian, was the director of this hospital. The doctor knew very well that I was a Jew, but he ordered me to not say a word in Yiddish and taught me to cross myself. He told everybody else that I was his distant relative. He brought me food and toys.

I stayed there over a month until my mother took me back home. As it turned out I was not the only one whom Drozdovski helped. Fascists hanged the doctor for helping Jews in the central square in early 1942.

Vinnitsa region, including Tomashpol, became a part of Transnistria 11, i.e., was under the Romanian rule. In October 1941 a ghetto was organized in Tomashpol. Our street and a few adjunct streets were fenced with barbed wire and there were guards at the entrance gate.

I cannot tell any details about our life in the ghetto. Few episodes are imprinted in my memory. They are associated with a common feeling of fear, hunger and cold. When we managed to get some potato peels we baked them on a makeshift stove and my mother made flat cookies of them. Fascists occasionally threw sausage and sandwich leftovers to the children as if we were dogs. This was a luxury.

My mother went to see our acquaintance in the village that had our cow to ask her for a little milk, but the woman refused. I remember that policemen captured my mother once when she was bringing food to us. She was made to run the gauntlet and each policeman hit her with a whip. She was almost beaten to death.

My mother couldn’t walk for a few days. An old woman from Moldova 12 attended to her. This old woman lived in our house. We also gave shelter to a 12-year-old boy from Tulchin living in our house. The old woman prayed beside my mother murmuring Jewish prayers. I need to say that even on the hardest days she started her day with a prayer. She fasted at Yom Kippur although almost each day in the ghetto was fasting.

My brother was a very bright boy. He managed to get out of the ghetto and somehow he brought sugar beetroots from the sugar refinery that saved us. He was captured by policemen several times. Once they beat him so hard that he was ill for a long time.

I also remember when a Romanian guard came for my brother. He had a gun and wanted to shoot my brother when he saw our dog with its puppies near the doorway. The puppies were white and furry and the guard began to play with them and probably forgot why he came there.

There was no more shooting, but inmates of the ghetto were dying from hunger, cold and diseases. In late 1943, before liberation, Germans took over the ghetto again. The situation grew worse.

We were ill. My sister had typhus three times: spotted fever, enteric fever and relapsing fever. She had high fever and my brother and I leaned on her to get warm. And the Lord guarded us! We were sleeping leaning over Polina, but we didn’t contract her illness, but we had lice. Cold, hunger and lice: these are my major memories of my childhood spent behind the barbed wire.

In late 1943 retreating German troops came to Tomashpol. They really became brutal. They made plans for the liquidation of the ghetto and drew up lists of Jews for extermination. Fortunately, they failed to implement their plans.

In March 1944 Soviet troops liberated Tomashpol. My uncle, Aunt Rieva’s husband Samuel Rachelgauz, came to the town with them. He didn’t know us and we had never seen him before, but Aunt Rieva, who was in evacuation in the Urals, kept writing her husband that if he came to Tomashpol he should find our family. She didn’t know about us. Rieva described her relatives to her husband: my father, grandfather, my mother and Aunt Leya.

I shall never forget this day. My sister had another attack of typhus and my brother and I were lying beside her covered with all rags that we could find in the house. Aunt Leya was trying to keep my uncle in the doorway telling him that we had lice and were infectious, but Samuel came into the house, took my sister in his arms and began to cry. Then he took a loaf of bread out of his bag. My mother screamed to him that he should give us only a little bit and my uncle began to give us small pieces.

For a few days we had meals in a military field kitchen facility. Then the army moved on and we stayed in our house. Actually, our situation didn’t change. The cold and hunger were with us. My mother went out to do people’s laundry or look after their cattle and they gave her some food for us. Life was so hard. I still cannot understand how we managed to survive.

In summer 1944 my brother moved to Odessa 13 by a freight train. There he entered a vocational school and was accommodated in a hostel. He received a stipend and unloaded railcars for additional earnings.

After the war the father of a boy from Tulchin living with us came to pick him up. He was very grateful to my mother and asked her to marry him since fascists shot his wife in Tulchin, but my mother refused. She was faithful to my father for the rest of her life.

Our life was very hard. 1946-47 was a period of horrifying hunger and only our life in the ghetto could be compared with it. We were ill again. I had rheumatism and I was bedridden for almost a year. At night I cried from pain and my mother was sitting beside me.

In 1946 I went to a local Ukrainian school. Life was improving. My mother began to receive monthly allowances for us. They were peanuts. My aunt Rieva provided the most sufficient assistance to us sending my mother some money each month. We wouldn’t have survived if it hadn’t been for Aunt Rieva’s support.

My mother worked a lot washing floors, doing laundry, whitewashing and cleaning houses for other people. However, she couldn’t earn enough for a living and so my mother began to sell things. She went to purchase goods in Vinnitsa. She bought soap and paints and sold them a little more expensive in our village. It was against the existing laws and my mother was often arrested. I already knew that if my mother didn’t come back home in the evening I had to take her some soup or boiled cereal to a militia office. Sometimes she was released a few days later and once she was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment.

During this year my sister and I lived on what Aunt Rieva sent us. We also were provided free lunches at school for being orphans. I remember us taking turns to go to school in winter having one pair of winter boots. When my mother was released Aunt Rieva took my sister to the Far East and my mother and I remained at home.

There were many Jewish children in my class and there were no negative attitudes toward us before the Doctors’ Plot 14, when in the newspapers and on the radio they spoke about doctors being poisoners. This period of anti-Semitism made the attitude toward us at school much worse.

I studied well and my teachers often asked me to help other pupils who were not doing well. I enjoyed helping them. I went to help them do their homework and their parents often offered me food. I was always hungry.

I remember when Stalin died in March 1953 I was standing on guard of honor by his portrait at school. I didn’t take an active part in public life, but I became a pioneer 15 and joined the Komsomol 16 of course, since without this it was impossible to continue your studies or have a career. Besides, if I hadn’t done it, it would have raised suspicions and questions.

My mother tried to observe Jewish traditions after the war. She didn’t work on Saturday. There was no synagogue in Tomashpol, but my mother got together with other widows like her to celebrate holidays. They even baked matzah in our stove. She often visited my grandfather’s second wife Rosa. Rosa didn’t remarry.

Her son Moishe finished college in Kiev. He became an engineer and visited his mother with his family. I saw them once in the 1960s. I don’t remember Moishe’s wife’s or his son’s names. Rosa died in Tomashpol in the early 1970s and Moishe and his family moved to the USA in the late 1980s and I lost track of them.

I finished the 10th [last] grade in 1956 and moved to my brother in Odessa. There was nowhere to study in Tomashpol. My brother worked at a plant and rented an apartment. I was living with him. In Odessa I entered the Faculty of Economics in the School of Heavy Industry.

When I was in the 9th grade at school I met Yefim Rozenberg, a Jewish guy. Yefim was born into the poor Jewish family of a tailor in 1937. We met when he came on vacation during his studies in a Navy School. Then he went back to his school and corresponded. I liked him a lot. Yefim came to visit me in Odessa and proposed to me. I wrote my sister asking her consent. She was a year older and it was a Jewish custom that older daughters had to get married first.

In late 1956 we registered our marriage in a registry office in Odessa and that evening we had a celebration with our friends. In February 1957 we came to our hometown and celebrated our wedding at home. There were many guests. They were Jews from our town. There was Jewish food at the wedding: gefilte fish, chicken broth and stewed meat. Besides traditional food there were no other rituals observed at our wedding party.

We lived a few more months in Odessa: I was with my brother and he stayed in his hostel until we received a small room at the plant. My husband sailed on his boat and I worked as a rate setter at the clock plant. We lived in Odessa for a few years.

In 1957 our daughter Svetlana was born. After my daughter was born I entered a Soviet Trade School. Life wasn’t easy: my husband was away and I had to work and study. At the age of two Svetlana went to a kindergarten and I took her home on weekends.

My husband earned well and didn’t spend much considering that he was provided a uniform and meals. It seems this was the first time of my life that I had sufficient food and could afford to buy clothes rather than wearing my sister’s clothes.

In 1962 my husband was transferred to serve in Western Ukraine, Ternopol [350 km west of Kiev], where he worked in the maintenance unit of Ternopol military garrison. In 1962 my son Mikhail was born. We lived in a small room in the basement and in early 1970 we received this apartment.

Although I married for great love our marriage failed. He was a rude man and mistreated my children and me. He only cared about himself and he couldn’t care less about us. He didn’t know what grade his children were in or whether they were ill or well or whether I had any problems.

I didn’t have a vacation once in all those 19 years that we lived together while my husband spent his vacations in the Crimea and the Caucasus and he never offered to take our children with him. They spent their vacations with me at home and he was seeing other women. I divorced him in 1976. Now he lives with his third wife in Germany.

My brother Lev finished a school of dentistry and worked as a dentist technician in Odessa. His wife Sophia is a Jew. She taught the Russian and Ukrainian languages at school. Lev has two daughters: Bella, born in 1960, and Svetlana, born in 1965. Both of them have higher education. Bella is a chemical engineer and Svetlana is a philologist. In 1991 Lev and his family moved to Israel. They live in Haifa. He writes me letters. He is very satisfied with his life.

My sister Polina lived in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, over 7000 kilometers from Kiev, in the Far East, with Aunt Rieva. She finished a geological survey school and began to work in the field of geological survey. My aunt and uncle moved to Severodonetsk and Polina stayed in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk.

Polina married Yuri Korotkov, a Russian, who was a geologist. He is a nice person and he treated her and my mother respectfully. Polina’s first baby died at the age of a few months. In 1966 her twins were born: daughters Svetlana and Yelena. My mother moved to my sister after her twins were born to help her raise the children and stayed to live there.

My mother died in 1986. Five years later Polina died of cancer. They were both buried in the town cemetery. There was no Jewish cemetery in the town then. Unfortunately, I didn’t see them after they moved. It was very expensive to travel such long distances. We corresponded and sent each other photographs.

Polina’s daughters live in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk. Svetlana became a geologist like her mother and father and Yelena is a teacher of the Russian language and literature. I have no contacts with them.

I worked a lot. I was director of a small store where I did all kinds of duties: of accountant, shop assistant or loader. I unloaded trucks with bread and other food products. I realized I had to complete my education and entered the extramural department of Vinnitsa Trade College. After finishing it I went to work as an economist in the trade department.

I got along well with my colleagues. We celebrated Soviet holidays together. However, I didn’t have close friends. My colleagues were Russian and Ukrainian. There were no Jewish employees in the department and I always sensed some tense attitude toward me. I guess it had something to do with my nationality, though I can speak fluent Ukrainian.

I worked long hours and after work I always rushed home to my children. I sometimes went to the cinema with my children and occasionally – to the theater.

I am fond of Ukrainian embroidery. I learned embroidery from my mother. I started new embroideries at the hardest moments of my life and I found consolation in them.

I actually raised my children alone. My daughter Svetlana finished an accounting school, but she didn’t work one day. She married Yanovski, a Ukrainian man. I tried to talk her out of it, not because he was not a Jewish man, but because he was rude and uneducated and that was why I didn’t like him, but Svetlana didn’t listen to me. He didn’t work and turned out to be a drunkard and an anti-Semite.

Svetlana has two children, born in 1985: Seryozha, born at the beginning of the year and Yulia, born in December. They live in Vinnitsa. My daughter’s husband beat his wife and children. They were always hungry and wore rags, but the worst thing is that he involved my daughter in drinking. I had a hard time trying to get her out of it. It took her a long time to recover.

Now Svetlana works as a home nurse of the social department in Vinnitsa. She has a low salary. I have to provide material and moral support to my daughter. After divorcing her husband she began to socialize with Jews. She is a member of the Jewish community now. Yulia studies in a Jewish school. In 1997 Seryozha went to study in Israel under an educational program, he lives and works there and is very proud of his new country. He rarely writes us.

Well, now, my son caused me a major problem. Mikhail was growing a nice kind boy. He studied well at school, was an active Komsomol member and was very reliable and accurate. When he was in the 10th grade he fell in love with his schoolmate Olga, a Ukrainian girl. She was an indecent girl. She married an ex-prisoner who worked in a chemical enterprise in Kherson.

My son went to the army. He studied at a school for junior sergeants in Moscow region. Later he finished a school of ensigns and went on service to the town of Yeniseysk in Krasnoyarsk region, 3000 kilometers from home. He was sent to pick military trucks in Ukraine and he came to see me in Ternopol. He happened to bump into Olga and went to see her without telling me a thing.

I don’t know what happened there, but he actually became a deserter. He failed to make his appearance in his military unit on time. I didn’t know where he was and the military office was looking for him. I went to Olga’s home several times, but it turned out they were hiding in a village where her relatives lived.

Then finally my son came home and departed to go back to his military unit. He was punished with one month in a cell and was expelled from the Komsomol. He had some other problems as well.

Sometime later Olga went to my son in Siberia and they registered their marriage, but she hadn’t divorced her ex-husband. She came here pregnant. I thought about it and decided ‘come what may.’ If he loves her so then she is his happiness. In 1987 her son Dima was born. I looked after the boy and after her.

Olga lived here with her mother for almost a year. I visited her every day bringing them food and gifts. Finally I managed to convince her to go back to Yeniseysk. Olga returned about two months later. She had a lover and they went to the Crimea. My son stopped writing her and was even upset that I continued to be in touch with her, but I was doing it for my grandson.

Later Olga got married the third time and had a daughter. However, she continued to drink and fool around. Dima was brutally punished at home. They called him ‘zhyd’ [kike]. My son brought her to court trying to get guardianship of Dima.

I became the victim of this: Olga’s brothers, ex-criminals, beat me near her home. They beat me for over an hour. They injured my liver and spleen. Her neighbors rescued me. I had to stay in hospital for over a month, but I was afraid of witnessing against them. I feared that they could just kill me the next time.

I stopped seeing Olga and my grandson. Recently I heard that Olga died of cirrhosis and Dima was homeless for two years. He lived at the railway station. Then he was in a boarding school. The Israel Embassy employees found him by his last name of Rozenberg. They support my grandson now. Dima stayed with me for some time, but we couldn’t find a common language: he is a very lonesome, embittered and absolutely uneducated boy.

A month ago the Jewish community arranged for him to go to a camp in the Crimea and on 1st September he will go to a vocational school near Ternopol. He will go to Israel then. I care about Dima.

My son Mikhail stayed to live in Yeniseysk of Krasnoyarsk region. He is a military and works in the militia. He remarried. His wife Svetlana is Russian. She is a wonderful wife. They have two daughters: Alyona and Christina. Mikhail supports us and sends money for Dima.

I didn’t have time for holidays and celebrations, reading or politics in my life. I had to survive and help my children and grandchildren. Many historical events went past me. It is sad, but such is life.

Hesed 17 and the Jewish community of Ternopol provide assistance to me. I’ve always wanted to move to Israel, but I couldn’t even think about it: life was hard and I had to think about raising my children and now I am old and sickly. I would dream to take a look at this country. I’ve always been interested in the situation in this country and felt spiritually attached to it.

Of course, I belong to the generation that grew up during the Soviet regime. I never observed Jewish traditions, except after the war when I lived with my mother. I speak Ukrainian, although I know Yiddish. I love Ukraine and I believe it’s good that it gained independence.

Many people have a hard life, but I receive a German pension as a former inmate of a ghetto. This enables me to support my health condition and even help my daughter and grandchildren. I find comfort for my soul in Hesed. I speak Yiddish with friends and we celebrate holidays: Pesach, Purim and Chanukkah. I try to forget about my problems, my hard childhood in the ghetto, but, regretfully, it is impossible to forget this.

Glossary