I, Inna Ilyinichna Rajskaya, was born in Leningrad in 1933. My paternal great-grandmother and great-grandfather – the parents of my paternal grandmother - were from Belorussia. Great-grandfather Elkona Borishansky ran his own business -- he dealt with drapery and was a fabric merchant. His wife, my great-grandmother, was a housewife -- I don’t know her name. I do know that the family lived in Minsk and that in addition to their house in Zakharievskaya St. there, they had a big estate in the Rodoshkovichy region.

My family background

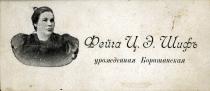

Their daughter, my father’s mother, was called Feiga-Tsipa Elkonovna Shif, nee Borishanskaya. She was born in 1867 in Minsk. She had many sisters and brothers, but I don’t know their names. After the [1917] Revolution some of them emigrated to the United States, but unfortunately the family lost contact with them. I myself never knew my grandmother; she died when my father was 14. My grandmother’s family was quite wealthy: after all, great-grandfather was a merchant. Everyone was remarkably kind; they brought up not only their own children, but supported other, poor families. I remember hearing about one family that they supported greatly - the Mazel family. All the children in my grandmother’s family, especially the girls, had their schooling at home: their parents hired tutors who came to the house. One of those teachers was my grandfather Iosif.

Iosif Ilyich Shif was born in 1870, but where – I don’t know. He lived his entire life in Minsk. I know little about his family, just that they were not very prosperous but tried nonetheless to educate their children. In 1890 Grandpa completed his education in pedagogy and became a teacher in a Jewish school in Minsk. He taught young children both in his own family and in other families, among them the Borishanskie children. And so it happened that my grandmother, Feiga-Tsipa Elkonovna Borishanskaya, and Grandpa Iosif fell in love and later got married.

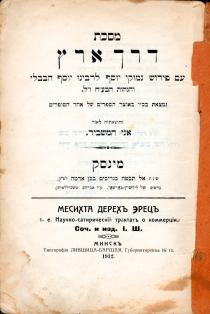

Grandpa wrote a book in Hebrew titled “Mesikhta dereh erezh”, a science fiction treatise about commerce. It was published in Minsk in 1912. We have this book at home. My father told me that the apartment they lived in was a large one. It was situated in the center of Minsk, and every child in the family had his own room. It was a house with all conveniences. Besides that place in Zaharievskaya, they had a big estate near Minsk with a vast orchard. They had their own horses. In addition, they had housekeeping servants, cooks, nurses, teachers, and governesses in the family.

After the Revolution the family, like others, was stripped of all their properties, and the apartment in Zakharievskaya was confiscated. They had to buy a small house in Minsk not far from the Opera theater.

It was a modest one-story building, but it was always scrupulously clean; my aunt maintained it rigorously. There were gorgeous plates and dishes and very beautiful silver spoons. Our family still has, for example, family heirlooms such as silver spoons with the inscription “A spoonful of happiness” written on them in Yiddish. These were presented by my grandfather to a niece as a wedding present. When I got married, my aunt (she was alive at that time) gave them to me, and now I handed them down to my daughter.

The family was numerous and very hospitable; relatives and friends were always staying with them. My Grandpa Iosif’s elder brother, a rabbi lived with my grandfather’s family. He was a very religious man, and thanks to him even after the Revolution Jewish traditions were followed in the house. I remember that when we visited Grandpa, I often used to see his brother reading Jewish religious literature. They always told me that one must not interrupt his studies. Everybody in the family treated Grandpa very kindly and with great respect and tried to behave in such a way that he would not scold them. There was a wonderful atmosphere in the family; they were able to treat each other with great kindness and affection. Even when one of the children was naughty, Grandpa stopped him not with a peremptory shout, but in ironical way. I remember very well how my Dad used to tell us: “Be quiet, grandpa is praying!”

My father, Ilya Iosifovich Shif, was born in 1904 in Minsk. From 1911 until the Revolution [1917] he studied in a Jewish school in Minsk. From 1920 till 1926 he worked in Minsk as a worker. In 1926 he moved to his elder brother’s [Elkona’s] in Leningrad, where he worked as a metalworker at the Metal plant and later was an accountant at the same plant. That’s where he met my mother.

My mother, Anastasia Nicolaevna Shif (nee Kuznetz) was born in 1902 in St. Petersburg. She didn’t know her own family, other people brought her up, and I know nothing about her parents. Unfortunately, I don’t know anything about how my parents met or about their wedding. At first they didn’t have anywhere to live and rented a tiny room. But after two years a room in the flat where my father’s brother [Elkona] was living become vacant, and my parents took it. That is where I was born in 1933. We lived together in the same flat with my uncle’s family until the war broke out in 1941. The family was a religious one and followed all the traditions. We observed Rosh-Hashana, Pesakh, Hanukkah and other holidays. My father’s cousin (who also lived in Leningrad) was a frequent guest in our house, and we always ate well. But I don’t think we followed the laws of kashrut, and neither my parents nor uncle attended synagogue.

During the war

During the war my father went to the front as a private. He served on the Leningrad front. Their unit was surrounded, and for several months they tried to break through this encirclement. Father told me about brutal fighting, especially with the Finns, during which our badly uniformed, poorly armed forces sustained great losses. Father got along very well with his fellow soldiers and officers. Though he was just a private in a reconnaissance unit, he was a rifleman. He got wounded and was sent to the rear – to a hospital in Sverdlovsk. When he was released from hospital he came back to Leningrad and somehow got a pass so that my mother and I could also return from Chkalovskaya region (where we had be evacuated). So in June 1944 Mom and I got back to Leningrad. After the war my dad worked as a director of a “Lentextiltorg” shop.

After the war, army buddies of my father who visited Leningrad stayed at our flat. I remember that very well. The flat in which we lived was a big communal one that had six rooms. Our flatmates were my uncle and aunt and two other Jewish families. One of these families also had its roots in Belorussia, but I don’t know anything about the other family. In addition, there was one more family – a Russian one, a very intellectual couple who had suffered in 1937. All these flatmates got on very well, regardless of their nationality.

My father came from a big family. Everybody spoke Yiddish and Russian in his family, and the elder brothers and sisters also had a good command of German and French. All the children were close. I had close relations with my relatives. We visited my aunts and uncles who lived in Minsk very often, and they visited us in Leningrad, too. My parents had close relations with father’s cousins, too. One of them, father’s cousin Elkona Borishansky, lived in Moscow but visited us very often and stayed at our flat for a long time.

My father’s sister Sore-Elka was born in 1888, and after her mother’s death [1919] she took the place of a mother for the younger children. She studied in Germany like her brother Elkona, and he and she visited Minsk on vacation. Sore-Elka got married to a certain Ura. She died in 1943.

My father’s sister Eli-Sheva was born in 1895 and lived with her father and elder sister in Minsk. In the war they were all put in a ghetto and died in 1943.

My father’s elder brother Elkona Shif was born in 1890. He moved to Leningrad after the Revolution. He was a highly educated person and studied in Berlin until 1917. He worked as an economist in Moscow and for a few years before the war was a bank executive in Leningrad. He had great authority and even after he fell ill with Parkinson’s Disease, the bank used him as a consultant and sent employees to his home to ask his opinion. During the war he was evacuated to Sverdlovsk. His wife, Bella Solomonovna Shif, a doctor, was drafted into the army and later transferred to a hospital to Sverdlovsk. Uncle Elkona died in 1953.

When Uncle Elkona got sick, not only my mother, but I, too, had to nurse him, as he was totally bedridden. He taught me a lot about my Jewish identity. He told me family stories, and from these I learned a lot about my grandmother, about my aunts, and about their children. He say so directly, but I now realize that he made clear nonetheless that everything that was happening in our country was unrighteous. I took care of him and talked to him a lot, and I am obliged to him for the awareness that I am a Jew.

Another of father’s brothers was called Max. He was born in 1893 in Minsk, graduated from a commercial school, and worked as a division head at the Ministry of Commerce in Belorussia. At the beginning of the war he was involved in the evacuation of the documents of the People's Commissariat, so he sent a car for his family in order to evacuate them from Minsk. But his father and sisters remained in Minsk. He learned of that only after a month, when Minsk was already occupied by the Germans. Max survived the war and died in 1946. In 1941 learned that his children, Yasha and Fanya , had escaped from the ghetto.

Fanya was a prisoner in the Minsk ghetto from 1941-1942. Her grandfather, two aunts and her mother were shot before her very eyes. She and her mother’s older sister tried to escape. The Germans fired at them. But Fanya managed to get to Rodoshkovichy, near Minsk, where her family used to rent a summer cottage, and from there went on to join a group of partisans, where she met her future husband, Yasha Axelrod. She and her family now live in Chicago.

Cousin Yasha Shif was born in Minsk in 1923 and finished school in 1941. When the war started, he was caught in the Minsk ghetto. Later he managed to escape and join the partisans. He was wounded in 1944. After the liberation of Minsk, Yasha went back there and entered law school, which is where he met his future wife, Roza. They had a daughter named Rita. He worked as an attorney in a legal advice office near Minsk, but now he and his family live in New York.

It was a miracle that our cousins survived the war. I maintain very close relations with them to this day, even though we are spread all over the world: they live in America, so we haven’t seen each other for many years and communicate only by means of mail and phone conversations.

Growing up

I was born in Leningrad and was reared for the most part at home. I don’t have any brothers or sisters. From the age of five I attended a German kindergarten not far from our house. There two sisters – both former teachers – taught us to read and write, and they also taught us German; my uncle [Elkona] insisted on that, as he had a perfect command of German and wanted me to know it, too. In 1941 I was sent into evacuation with children of the employees of the Mariinsky theatre. These children were leaving for evacuation, and I was taken with them through family connections. During the evacuation I was at first in an orphanage near Kostroma, then the orphanage was moved to Kostroma itself. In September of 1941 Mom arrived; she took me and we together to the Novotroitzk settlement in the Urals, where her distant relative Abram Alexandrovich Dobrovinsky, was a site manager of the building of the Orsko-Halilovsky metallurgical works.

After the war

When Mom and I came back from the evacuation, we found our room already occupied by other people, but since Father had fought in the war and was a disabled veteran, these people left and we got our room back. To tell the truth, there was practically no furniture in our room; apparently everything was burned during the blockade. Only a very few things that had belonged to our family remained, and these were only the things that had been taken and kept for us by a neighbor. After the war my father was in very poor health, and he soon had a heart attack. He wasn’t able to work the way he did before the war. Still, our family was exceptionally united, Father and Mother had a lot of friends who visited our house very often - for the most part these were Jewish families or mixed families in which the husband or wife was Russian.

Later, I started to study from the fifth grade. I liked history, chemistry and geography very much; probably because I had great respect for the teachers I had for these subjects. I particularly remember my history teacher, Raisa Solomonovna Ermanok - she was an outstanding teacher, a small, nice woman, who after the war treated all the children in the class with great kindness and interest. I didn’t feel any discomfort at school because of my Jewish parentage; clearly we had good teachers and a good student body, too.

As soon as I graduated from school in 1951 I applied to the University to study in the chemistry department. Even though I had good grades, they didn’t accept my application, and one of the senior women who sat in the selection committee quietly explained to me that it would be better for me not to apply to this department. It was clearly because of the climate of mounting public anti-Semitism. This was the first slap in my face. Why it was the first slap? Because I felt for the first time in my life that I was a social outcast because of my nationality! Then I applied to the Pedagogical Institute, but this time to another, department – geography, not chemistry – and I was accepted. I graduated in 1955.

After graduation I married Albert Grigorievich Rajsky. Albert was a friend of the husband of my girl-friend Tsilya Ravich; he and her husband had studied at the “Dzerzhinka” higher naval academy and served in the North. My husband is Russian, born in 1932 in Uglich, into the family of a clerk. His father was killed at front during the Great Patriotic War [World War II]. His mother had brought up my future husband and his elder brother alone. Both of them were naval academy graduates.

When I began to look for a job, I again had serious problems. This was because outwardly I didn’t look typically Jewish, and everything went on in the right way until I showed them my passport [which said I was Jewish].

Husband and children

In 1961 my husband was demobilized from the Navy because of me, or, rather, of because of my nationality. They gave him no hope of being promoted to a higher rank because his wife was Jewish. So he had to leave the Navy and started to work as a ordinary engineer in Leningrad.

At that time I worked in a Leningrad middle school, first as a teacher, then as a head of the curriculum department and later as the director. At present I am retired. It was only thanks to a schoolmate - she was my very close friend, and I communicate with her to this day – that I got my job. My friend had also graduated from the Pedagogical institute and worked at a school. In the middle of the school year her school had a vacancy for a geography teacher. The director of that school was a Jew named Safray, and thanks to him I got the job. He appealed to Gorono [the city’s public education department] and said that he felt I was the right person the post. Gorono assigned me to the job, so I got fixed up, but with great difficulties. It was the second slap in the face I experienced. I also experienced a very unpleasant situation when they were confirming my appointment as school director. This took place in the district party committee, and when the head of Gorono read out my biography, everyone woke up to the fact that I was a Jew. But they nevertheless confirmed my appointment.

Unfortunately, I have a very bad command of Yiddish, and I only understand it a little. I regret that I don’t know Yiddish, that I can neither write nor speak it. My father knew spoken Yiddish but didn’t know how to write. Why do I regret this? It is better to know than not to know, isn’t it? Lenin said in his time: «As many languages you know, as many times you are a man». That is, I could understand the culture and world outlook of my native people through the language. Now I only realize that I am Jewish, but I don’t know how to say it in Yiddish.

My daughter Elena was born in 1961. She graduated from the school in Leningrad, then from the Financial economics institute. I have two granddaughters, Anastasia, born in 1989, and Alexandra, born in 1991. My daughter’s husband is Jewish on his mother’s side; his father is Russian. Nevertheless both I and my daughter continue to feel, to realize, that we are Jews. We tell a lot about Jewish culture to our little girls: to my granddaughters. Besides, my husband – their grandpa - takes an active interest it, too: he reads books on Israeli history, on Judaism. Anastasia knows quite a bit about Jewish culture and about Israel. She knows about all our relatives, with whom we correspond or communicate by telephone, knows where they all live.

Recent years

Why didn’t we ever go to Israel? It was connected with my husband’s work: first because of his military service, second because for 26 years he worked at the famous “Rubin” enterprise, which is now well-known all over the world because of the tragic events with “Kursk” [the nuclear submarine that exploded and sank]. He had so-called “zero access” classification [that means he had an access to very secret documentation], so we never even considered such a trip -- we realized that they would ever have allowed us to leave.

Throughout my life, I’ve had friends of different nationalities. I have several friends with whom I’ve been close from my youth. I was on friendly terms with a girl named Naimi Yakerson, who lived in our house, and who now lives with her family in Israel. My second close girl-friend, of whom I have already mentioned, was Tsilya Ravich, we are close friends to this day. We spend a lot of time together, and visit places or go to the country when we had a chance. I have one more girl-friend, Lyalya Simkina, who moved to Poland. We often see each other, Lyalya Simkina has even visited me, and I’m the first person that Musya Yakerson visits when she comes from Israel.

Most of my friends are Jews. But now, unfortunately, we are dispersed over the world. Our closest friends, the Khanins, now live in New York, though they visited us not long ago - in May. We always traveled a lot and tried to show to our daughter many places in Russia. We traveled often to Belorussia, where my cousins lived before the emigrated to the United States [after the 1917 Revolution].

After the Revolution, my parents were afraid to keep in touch with the relatives who had emigrated to America. Only my father’s cousin Elkona Borishansky, who lived in Moscow, maintained contact with them, but after his death those relations ceased somehow. Now I maintain close contact with my cousins – Jakov Shif and Fanya Axelrod, who live in New York and Chicago; and also with my nieces. We often communicate by telephone and write letters. They try to help us a little in some way. Certainly, all the recent changes in life in Russia are pleasant to a certain extent, because now there is no anti-Semitism – to be sure, I mean the state attitude toward Jews, not anti-Semitism in private life.

When Putin was in New York and met with Americans in our Russian Consulate, there were Jews present. And generally speaking, the attitude towards Jews now has become better. Unfortunately, however, anti-Semitism can be often felt on the everyday level. My son-in-law often have problems because he has a very Jewish appearance, and more than once drunk members of NRE [Russian National Unity is the neo-Nazi youth organization in Russia] taunted him, and even threatened him – it is very unpleasant. Certainly, I would like Russia to join the European world and not to create something special, something Russian, which is what many people are still trying to do here.

[Inna Ilyinichna is an intellectual woman of 68. She remembers many details of the life of her paternal ancestors well and is very proud of her relatives. She often emphasizes the harmony in which they lived. When she tells about their lives, one can feel that she suffers for her relatives who have perished in a ghetto. Inna Ilyinichna considers it her duty to recount the intellectual beauty and strength of mind of her relatives to those, who investigate the life of Jews before and after the Holocaust. She wants to keep alive for future generatio the memory of the grandeur of her kinsfolk.]