Igor Brover

Odessa

Ukraine

Interviewer: Nicole Tolkacheva

Date: December 2004

I met with Igor Yakovlevich Brover at his home. He lives with his spouse Alla, a sweet and considerate woman, in a five-storied house built in the 1960s in Derevianko Square. A small two-bedroom apartment is notably clean. Its interior is plain. There is a big photograph of their deceased daughter behind the glass. The host is a handsome black-haired man with resonant young voice, very reserved and laconic. His Russian language often sounds with a typical accent for Yiddish. Igor Yakovlevich willingly told me the story of his family. He got sincerely upset, when he had no answer to my questions.

My family background

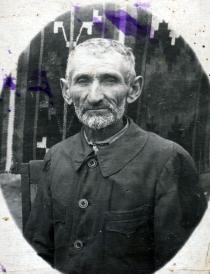

My paternal grandfather Samuel Brover was born in Petroverovka village [present Zhovten'] in 1878 [editor's note: Petroverovka was a small town in Kherson province Tiraspol district (present Odessa region). According to the census of 1897 there were 1 749 residents and 819 of them were Jews]. My grandfather was a shoemaker. In the middle of the 1890s my grandfather married Udia, a Jewish girl from his town. They were probably poor since before the revolution of 1917 1, when my grandfather was already married, he went to America looking for a better life. He stayed there a little over a year and then returned home. My grandfather knew Yiddish and could read and write in it and he also knew Russian. My grandfather was quiet, but persistent. He never served in the army. He wore common clothes. He didn't wear a hat or have payes. For a long time I thought that my grandfather wasn't religious; I never saw him praying, but when we were in evacuation during the Great Patriotic War 2, my sister Rosa and grandmother once went to my grandfather's work to come home with him. Rosa saw my grandfather and another old Jew swaying back and forth saying something in sing-song voices. My grandmother explained that they were praying. My grandmother liked the Soviet regime since he saw that there were no pogroms or attacks on Jews, but he never became a member of the Communist Party. When collectivization 3 began in 1928, in Ivanovka village of Odessa region the Jewish kolkhoz 'Schtern' ['star' in Yiddish] 4 near the Yeremeyevka station in 50 km from Odessa. My grandfather and grandmother and their 16-year-old son, my father, moved to Ivanovka and joined the kolkhoz.

My paternal grandmother Udia Brover (I don't know her maiden name) was also born in Petroverovka in the 1870s. Her Russian neighbors called her Olia. She had no education, but as my father told me, she did not only keep the house, but also had a small business, when they lived in Petroverovka. She owned a small store where she was selling consumer goods and food. I remember that grandmother Udia could do quick calculations faster than I could at the age of 18. She was smart and vivid and had an explosive character. She was also a very good housewife. When she cooked fish, it smelled across the yard, and then other housewives shouted: 'Baba Udia ('baba' is informal addressing an old woman), did you cook fish?' 'Yes, I did. Come by and try a piece.' My grandmother usually wore dark shirts and long skirts. I remember that she almost always wore a kerchief on her head. I think my grandmother and grandfather followed kashrut. They didn't celebrate Sabbath since there were no days off in the kolkhoz in summer. They celebrated major Jewish holidays Pesach and Rosh Hashanah, but I cannot say whether they followed all rules since even now I don't know them. I remember my grandmother washing the casseroles and taking them to the attic to take them down, when she had to cook something kosher for the holidays. I know that grandmother Udia gave birth to eleven children, but only my father survived. What happened to their ten children was never discussed. I think my grandmother and grandfather lived through pogroms 5, since this subject was thoroughly avoided in the family.

My father Yakov Brover was my grandmother's youngest son. He was born in Petroverovka in 1912. He went to cheder and finished three forms at school: for his time he was thought to have got sufficient education. His mother tongue was Yiddish, but he couldn't write in it. He could write in Russian, though. My father was relatively tall, his height was one meter seventy five centimeters [ca. 5'9"], of average constitution, dark-haired. When I remember, my father worked as a crew leader in the kolkhoz, i.e., he was responsible for all housekeeping activities.

He was energetic and hardworking and very smart since one couldn't manage Jews without certain skills. He had skills. He was reserved, not too strict, rather witty and looking for compromise; he could come to an agreement with any person. My father met my mother in the kolkhoz.

I hardly know anything about my mother's parents. I don't know where they lived. All I know is that my grandfather's name was Isaac Popovskiy. My mother's parents died of cancer, when my mother, the youngest in the family, was 12. After their parents died, my mother, her brother Mikhail and sister Raisa went to live with their aunt, and they lived with her a few years. Regretfully, I don't even know this aunt's name. My mother's older sister Riva Popovskaya was born in 1908. I knew aunt Riva, she lived in Komitetskaya Street in Odessa. She wasn't married and had no children. Riva perished in Odessa during one of the first air raids in 1941.

My mother's brother Mikhail Poplavskiy was born in 1910. He finished a Military Political College in Leningrad. Then he was political commander of a regiment. My uncle was married twice. His first wife Tatiana Serghendler lived with their son in Odessa. Their son Adolf and I were friends. His second wife Claudia was from Leningrad. They had a son named Vilia. Uncle Mikhail disappeared in a battle near Smolensk during the Great Patriotic War. His second wife Claudia and son Vilia live in the USA.

My mother Ida Popovskaya was born in 1912, but I don't know where. My mother went to school for three years. She spoke Yiddish, but she could only write in Russian. Like my father she came to Ivanovka in 1928. My mother was a receptionist in a milk shop where milk was processed into cream in a separator. In summer, when there was a lot of field work to do she worked in the field harvesting crops. My mother wore common clothes like all other women in the kolkhoz: a skirt, a shirt and a kerchief. She was tall and thin, had black hair and bright beautiful face. She was hardworking and restless. She had hot temper.

In 1932 my parents got married. They were both 21 years of age. They had a civil ceremony, but no religious wedding. I was born on 12 October 1935. My Jewish name was Israel, but I was called Igor. We lived with my grandmother and grandfather in a small one-storied house near the kolkhoz administration in the very center of the village. It was a lively spot with other houses and sheds. My father, mother and I lived in one room, and my grandmother and grandfather occupied another room. There was plain furniture in the house: a wooden table, stools and long bench. There was also an old wardrobe and nickel-plated beds. There was china or faience crockery in the house. There were wood stoked stoves in the kitchen and my grandmother's room. We didn't have a garden, but our neighbors had gardens and vineyards. We kept livestock: goats, cows, sheep, chickens and geese. My mother, grandmother and father took care of them. I wasn't afraid of our domestic animals and never had any problems with them since I was growing up in a village.

Growing up

People got up and took to work very early in the village. My father was the first in the family to get up. He woke up the others. My mother and grandmother woke me up and got everything ready for me to go to the kindergarten. Grandmother Udia did the housework and my mother went to work. On her way there she took me to the kindergarten. There were about twenty children and two tutors in the kindergarten. We played with toys or with one another like in any other kindergarten, and our tutors read books to us. My mother picked me at 7 at the earliest. When we came home, my grandmother had dinner waiting for us. My grandmother did the cooking in our family. We waited till everybody was home to have dinner together. We set the table together and together we cleaned it. It has always been like this in our family. My favorite food has always been gefilte fish and cutlets. However, we rarely had them. We usually had borshch [a traditional Ukrainian beet soup], and boiled wheat cereal or corn. We seldom had buckwheat since it was rarely available. It wasn't decent to be capricious about food. We were to be grateful for what we had. The only thing I wasn't allowed to do was to refuse milk that I didn't like, though we had milk from our cow.

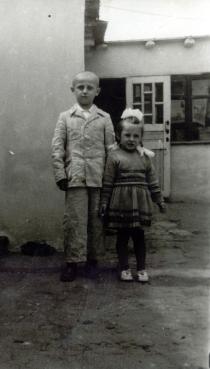

In 1939, when I was four, my sister Rosa was born. I don't remember anything about it, but I remember that my mother always gave birth at home. There was a medical office in the village where a very good assistant doctor worked. He could provide medical first aid, do a surgery or assist at birth giving. So he came to tend to my mother. Rosa stayed at home with my grandmother before the war. When I was at home, we played in the garden. We fought at times. In the evening my mother or grandmother put us in beds, but they didn't sing or tell us fairy tales. They usually said: 'Go to bed and sleep'.

Sometime my mother and father took us to the market in Odessa. A truck from the kolkhoz transported milk to the market regularly and villagers could drive in this truck or walk 5 kilometers and take a train to Odessa to do their shopping. In the town my parents visited my mother's sister Riva. They always brought presents from such trips. I always looked forward to these moments in my childhood. They usually brought sweets, khalva or sausage that I liked a lot. The favorite food of the family was herring. Even when I was ill I only asked for herring. They also brought a piece of clothing since they didn't sell clothes in the kolkhoz. My parents also brought books. My father didn't have time for reading, but my mother liked reading something to us or telling us stories. We spoke Yiddish in the family and before school my Yiddish was better than Russian. We spoke Yiddish with our neighbors discussion family and home matters or politics and singing songs. For example, there was a song: 'Gewoil iz Hawer Stalin' ['Be well, comrade Stalin' in Yiddish]. They praised Stalin and his acts, as was common at the time. We liked Soviet holidays. My favorite holiday was 1 May, when we could go to a mayovka [mayovka - this word derived from the name of the month of May when people organized picnics with friends and families. Schoolchildren, students and adults used to arrange such outings enjoying the food and beverages], when everything comes back to life and we could just run on the grass.

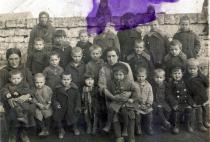

There were about 500 people working in our kolkhoz. Probably, about 150 of them were Ukrainians and the rest were Jews. Chairman of the kolkhoz was a Jew. His surname was Fabricant. The kolkhoz members built houses and they are still there, one and all beautiful, under the red tile roofs. They built a school. This was a Jewish school before the war. They taught children in Yiddish. After the war they switched to Russian. The kolkhoz was in the steppe and there were fields all around. There was no water reservoir and they made an artesian well, the first in this area, installed a pump and it pumped water for the whole village. We had running water in the house. Only in our village there was electricity. A generator supplied power to houses between 8 in the morning through midnight. Our kolkhoz 'Schtern' was one of the best in Rasdelnia district. There was a big orchard. Apricots were transported to Leningrad. They grew wheat, vegetables, melons and watermelons in the kolkhoz. The kolkhoz members were paid in agricultural products for each working day. While in other kolkhozes the rate was 200 grams per day, in our kolkhoz it was 2 kg. There was no market in the kolkhoz. Every family kept livestock and received food products as payment for work in the kolkhoz. Life was good before the war. However, there was no Jewish community or rabbi or synagogue. I don't think there was one religious Jew in the kolkhoz.

Our family and the family of chairman of the kolkhoz Fabricant were friends. His wife was director of school. My parents had another friend: accountant Berkun, a Jew. We still keep in touch with their families. We got together on Soviet holidays, or they just dropped by for a chat. They were all educated people, liked to read books and newspapers and liked writing letters. There was a library in the kolkhoz. We borrowed books from there. My parents were not religious. They appreciated the Soviet regime knowing Jewish misfortunes before the revolution. We were an average family. Our parents worked to make our living. My mother or father never went on vacations. They worked all of their life. My mother was devoted to our family and the children. She loved us dearly. We kept closely in touch with my mother's family. Aunt Riva often came to see us and my parents visited her. They corresponded with uncle Mikhail, and he spent his vacations with us. He always brought us gifts. When the Finnish war 6 began, my father was recruited to the army. He was a first sergeant in infantry. He had his feet frost-bitten there and returned home with big red toes.

During the War

In the first days of the Great Patriotic War in 1941 it was quiet in the village. There were no air raids. My father was recruited on the third day after the war was declared. When my father was leaving I cried not knowing when I was going to see him again. We didn't know about him for over two years until he found us and then we corresponded till the end of the war. Regretfully, my father's letters were lost. My father was in the rank of first sergeant. He was a driver for the commander of division. Then, when 'katyusha' units were introduced he began to drive one of them. He went as far as Budapest, from Budapest he was sent to Tiraspol, and from Tiraspol he demobilized in the end of 1945 and came to his village. During the war my father joined the party.

The Jewish population of our village evacuated in early July 1941. There were only Ukrainian and Russian residents left. There were 5 of us evacuating: my grandmother and grandfather, my mother, I, Rosa and my younger sister Raisa, born in early 1941. We rode in wagons: one wagon ridden by three horses per each family. Our neighbor's family was with us. Her husband was ill and was not subject to service in the army. He and my grandfather took turns to hold the reins. On our way I saw our troops, tanks and planes. German aircraft bombed us and we took to hiding. Then, at a station we took a train, and this was my first railroad trip. We arrived at Ursat'yevskaya town in Tashkent region in Uzbekistan. From there we had a truck to take us to a small kishlak village not far from the town.

The houses in this kishlak were built from the mixture of straw and clay. They had flat roofs where the villagers dried apricots and grapes. We were accommodated in a small room in one of these houses. Our landlords were good to us. There were no demonstrations of antisemitism. My mother worked in the field and my grandmother and grandfather were with the children. I picked the Uzbek language promptly and even learned to curse. The houses in this kishlak were heated by burning dry cow manure gathered when the cows came home for milking at twelve o'clock. The accountant Berkun's family was in this same village, and I went to gather manure with his daughter Clara who was three years older than me. Once an incident happened: she collected manure faster than I and I got so angry with her that I put the only dung I managed to get on her head. My only excuse was that I was so young. Clara and I still keep in touch. She lives in Israel now.

Since there was no Russian school in the kishlak, my grandfather taught me. Of course, I preferred playing outside, but my grandfather was strict and made me study. He had no books or an ABC book. He found old Russian newspapers and taught me to read. We stayed in the kishlak for about two years before we moved to Ursat'yevskaya. My mother began to work as an inspector in the financial department, I went to school, my grandfather became a janitor and my grandmother looked after my sisters at home. Our family received bread per cards. My mother worked in the financial department and received 500 grams, my grandfather - 400 grams as a janitor and we, children - 300 grams each. When I went to school, my mother made me a bag from some pieces. There were no books. I wrote on blanks that my mother brought from work. They were stapled together like notebooks. I finished the first form in three months. My grandfather prepared me well. I shared my desk with the boy whose father worked in the military registry office. I think he was a military commandant. We were hungry, and our teacher gave each of us a little piece of brown bread during an interval, but this boy had slices of bread and butter every day and he didn't need these pieces. He didn't want to study. I did his tasks for him and he gave me his bread. I ate brown bread that he had and took white bread to my sisters Rosa and Raisa at home. They were so used to it that when I was coming home from school they were waiting by the window and seeing me they ran to me and got this bread out of my bag. Usually my grandmother took it away from them to prevent any argument and gave it to them by little pieces.

After the War

We stayed about a year and a half in Ursat'yevskaya before we reevacuated in late 1944. We took a train home. The trip lasted a month less three days. On our way my grandfather died and we buried him in the Jewish cemetery in Kotovsk town. We sent our baggage separately. Since there were problems with salt at that time we sent a bag of salt with the luggage. Neither the salt nor our most valuable things reached us. They were stolen. We came to our village hungry and cold. Our neighbors helped us and we felt at home again. The kolkhoz gave us the same house where we lived before the war. Of course, there were no belongings left at home. We were sorry they were gone. My parents worked so hard to get them. My mother worked as director of the food and materials storage of the kolkhoz. In late 1945 my father returned and life became easier. He worked as crew leader at first and then he became manager of a mill and the buttery at the same time. Besides, we had a cow, goats and chickens. I was to take care of them. All kolkhoz members having cows had milk hauled by a truck to sell in Odessa. For the money we got from sales we bought food and clothes. In 1947, when bread coupons were cancelled I brought home four loaves of bread and everybody pounced on it, but my grandmother took it away saying: 'You need to take a little piece at a time or else you will feel ill'. So she gave us a little piece at a time.

Life in the kolkhoz was gradually improving. Almost 60% of Jews returned to the village. The Ukrainian population was the same. The former chairman Fabricant perished at the front and we had another chairman: Shargorodskiy, a Jewish man. After the war the kolkhoz didn't have the status of a Jewish kolkhoz, but it was still very advanced. There was electric power, running water and a radio in each house. My younger sister Raisa went to the kindergarten. Rosa and I went to school. Rosa went to the first form at the age of 6, and I went to the 3rd form. There was only an elementary school in our village and after finishing it I went to a 7-year Ukrainian school in the neighboring village of Yeremeyevka.

We studied in Ukrainian, and after finishing this school my Ukrainian writing was better than Russian. I liked mathematic and liked the teacher of mathematic in my new school. He was an older man. He spoke Ukrainian. When somebody failed to do his problem he called me to the blackboard. There were about 25 of us in the class. About six of them were the same age with me and the rest of my classmates were 18-20 years old. I was the only Jew in my class, but I never faced any prejudiced attitudes. I shared my desk with a Ukrainian boy Volodia Basenko. Volodia lived in my village and we were friends. There were a few clubs at school, but I didn't have time to attend them. Every day Volodia and I covered 5 kilometers to Yeremeyevka and then walked 5 kilometers back home. I came home late and had to do my homework. Then it was time to go to bed. On weekends I usually played volleyball and football with other boys. We often played games, mostly dominoes, with our parents at home. My parents always paid attention to my reading and studies, though they only had three years of school education. My father could solve a mathematic problem for the 6th form. That's how smart he was. During my summer vacations I worked as the artesian well motor mechanic to support my family. I liked this job very much.

My sisters and I grew up in a Jewish kolkhoz and knew that we were Jews. Though we didn't face any antisemitism in our childhood, we were prepared for it. My mother and father made us understand, directly or indirectly, that we might face unfair attitudes being Jews. They always said I had to be ahead of the others or else I would never reach anything in life and I always tried to follow this indication. Besides my studies at school, I had to help my father with his trips to Odessa to sell milk and other agricultural products at the market. Sometimes my mother accompanied him in those short trips. We bought clothes and shoes for the money we got from sales. In 1950 I finished the 7th form and since there were three children in the family and there was another baby expected it was decided that the oldest one had to get a profession. In 1951 my brother Samuel was born and I went to a vocational school in Odessa.

I studied to become a mechanic in the vocational school in Mechnikova Street in Odessa for two years. I lived in a hostel. We attended lectures one day and had training on the next day. During the first year we had training in our school shops in 12, Kanatnaya Street, and in our second year we had training at the Odessa shipyard. At that time there was rabble studying in vocational schools. After the war there was lack of workers at the plants and in 1947 - 1948 young people from rural areas were almost forced to go to vocational schools. They were mainly people without education and those who came from problem families. Such people could provoke, and they did, conflicts based on national grounds. However, there were also normal guys there and I became friends with them. It was hard to study in such conditions.

I faced antisemitism on the state level for the first time when I was finishing my vocational school in 1953. There was demand for motor mechanic in the shipyard and our group of 30 graduates went there to be examined by a commission. Of course, I was eager to get a job at the shipyard and I got the highest point at the commission. They told us to wait for the results. Then they called everybody, but me and Odesskiy, both Jews, and two guys from a children's home. This was too much for me, and I asked them why they didn't employ me considering my highest marks. They replied: 'You are not employed and that's it'. They never explained their motives, but we understood. I remember well that this happened during the period of the "Doctors' Plot" 7, and Jews were having problems. They could say 'here is a zhyd' [abusive word for a Jew] at the market, or 'what are you doing here, there is nothing for you here'. They were particularly rude with women. They were not so brave with men, but they frowned on them, anyway. I was sent to the shipyard to work as a mechanic. There were many Jews at the shipyard and we were friends. Many of them live in the USA now. Since I didn't have secondary education I went to an evening school where I finished the 8th and 9th forms. There were prejudiced attitudes toward Jews at the shipyard. Of course, promotions were out of the questions. Jews were better than many others, but there was no way for professional growth.

In March 1953 there was information in newspapers and on the radio about Stalin's health condition. They gave the status of his health every hour. Of course, we were anxious. When they announced that he died, it was a tragedy. Women were crying and men looked dispirited walking with their heads down. We were born during Stalin's rule absorbed love for Stalin with our mothers' milk, we were raised with the name of Stalin and prayed to him, as if he had been God. It was very hard to think that he was dead and watch this mourning. That is why perhaps after the 20th Party Congress 8 I felt a real shock. We didn't know how many people were put in prisons or killed. When we got to know about it, we lost faith in the government. Though after Stalin's death people stopped disappearing, the Soviet regime always stood on people's fear.

In the middle 1950s my sister studied in Odessa after finishing school. Rosa entered the College of Loans and Economics and Raisa studied in the Technical School of Finance and Loans. My parents, grandmother and my younger brother Samuel also moved to Odessa. We bought (I don't know the details) a small house in the vicinity of Bugayevka in the suburb of Odessa. My father worked at the leather plant where he was a package operator and my mother didn't work since my brother was small. Unfortunately, Samuel lost his hearing after a disease. He was deaf, but he could read from lips. Samuel studied in a special school at the 11th station of the Fontan [resort district of Odessa]. There was only one room in the house while there were 7 of us, so we had to install a partial in the hall to make another room. Each of us slept on a folding bed and only our parents had a nickel-plated bed. On weekends our old grandmother was at home with my younger brother, and we usually went to the cinema or theaters. My parents sometimes joined us. We liked musical comedy, but also went to operas. There were problems with books even in Odessa after the war, but we managed to get books. We liked reading. We particularly like books by Boris Polevoy 9.

There was a mandatory two-year period of work requirement after finishing vocational schools 10. After two years of work at the plant I was recruited to the Navy in 1955. At first I served in a training military unit in Lomonosov near Leningrad and then I served on a ship in Severomorsk. I didn't have any nationality-related problems in the army, basically. I was physically strong and had independent character. Besides, I was Komsomol 11 unit leader of the ship. Of course, there might have been intrigues behind the curtains, but they had nothing to do with me. When I was serving in the army, the Hungarian revolution [1956] 12 happened. All I remember about this period was the propaganda. We didn't understand things then and supported the actions of our country. I demobilized in 1959. Shortly after I returned my grandmother died. We buried her in the 3rd Jewish cemetery.

After the army I went back to work as mechanic at the shipyard. In 1960 I entered the evening department of the Machine Building College where I studied four years. I continued my work at the shipyard. We had to work in three shifts. This was hard physical work. After finishing this college I became a technical mechanic. I became a foreman and then senior foreman at the plant, but there were no further promotions because of my Jewish identity. My management told me that I was working well, that I had good knowledge and was a good tutor for young people. I had apprentices who were promoted later, but that didn't happen to me.

In summer 1960 I met my wife to be Alla Perelman. My mother brother Mikhail's son Adik, my cousin brother, was my friend. In the yard of his house in Razumovskaya Street where he lived with his mother, there was a small shoemaker shop. Once Alla brought her shoes to this shoemaker and we met. On 15 March 1961 we got married. We've been together ever since. Alla was born in Odessa on 25 August 1936, in a Jewish family. Her father Alexandr Perelman was a lecturer at the Flour Grinding School. Her mother Raisa Markovna was a lab assistant at a bakery and then she was a housewife. During the war their family was in evacuation in Tashkent and then moved to Omsk. Alla's older sister Valentina was married and lived with her family by the time I met Alla. Alla finished the Food Industry School and worked as lab assistant at various bakeries afterward. She was an excellent lab assistant and knew her profession well, but she was held back from promotions. She often heard: 'Where will you go if you quit? Nobody would employ you'. When we got married I convinced Alla to take a job of a lab assistant at the plant of stove units and she began to earn more.

After the wedding we moved to her parents in Khvorostina Street. They had a two-bedroom apartment on the third floor in an old house near the town garden. We lived in one room and her parents lived in another. My wife's family wasn't religious and we didn't observe any Jewish traditions. In late 1961 our daughter Tatiana was born. One month later my father-in-law died. Of course, I had to take care of my family and my mother-in-law. I lived with my mother-in-law for almost ten years and we never had any conflicts. We got along very well. Raisa Markovna always supported us and we helped her. When we moved into another apartment we often visited each other. She died in 1994 and was buried near her husband's grave in the Jewish cemetery.

I had to work a lot, but I always spent weekends with my family. We went for walks or visited my parents. My wife and I liked musical comedy. Alla was very fond of opera and had a big collection of records, but we liked musical comedy more. This was the period when Odessa Musical Comedy Theater was at the peak of its popularity. We watched performances with Vodianoy, Dynov and Dyomina - they were stars. There was a good ballet group in this theater. I knew their names, but I've forgotten them. We watched the 'White acacia' performance [operetta by the famous Soviet composer Isaac Dunayevskiy The act is about life in Odessa], and all performances with Vodianoy [Vodianoy, Mikhail Grigorievich (1924-1987) - popular theater and movie actor, Jew, in Odessa]. Once a week we went to the cinema. We watched all new movies standing in lines to get tickets before. We usually went to the movie theater named after Voroshilov 13, it was called 'Zirka' later, in Chicherina Street. There was no television at that time, and people read books. I always liked reading, but had little time for it. Besides, I had to help at home and spend time with our daughter. So I gradually got to reading only newspapers and magazines. We subscribed to 'Rabotnitsa' [Woman-worker, a monthly social and political magazine issued in Moscow], and Odessa newspaper 'Znamia communisma' ('The banner of communism', but I preferred 'Izvestiya [Izvestiya - News, daily communist newspaper published in Moscow.]

In 1967, during the war in Israel [Six-Day-War] 14, I was recruited for regular military training in Nikolaev. There were lectures about it in our unit. There were a few other Jews in my unit and we sympathized with Israel, but didn't like Arabs. We were very upset about the termination of diplomatic relationships between the USSR and Israel. This was done outrageously out of negative attitude toward Jews and to play up to Arabs. There was an incident with the radar station then. The USSR furnished a state of the art radar station to Egypt. At 12 o'clock, when all Arabs were praying, an Israel plane hooked up this station and took it away. The Arabs were horrified. During the war in 1973 [Yom Kippur War] 15 our emotions were no different and we sympathized with Israel as we did before. In 1968 Soviet troops occupied Czechoslovakia [Prague Spring] 16. We didn't quite understand what was going on. Only much later, when there were publications on this subject, we understood that we didn't have to get involved there.

In the 1960s my parents received an apartment in Korolyova Street. We had a nice family and we loved each other much and visited each other at least once per week. My mother and father were the first ones whose advice I looked for, but they never interfered in my personal life. They always said: 'You take care of yourselves, you are grown up people'. We always supported each other. They were doing all right, but I was always there to help them, and my father was always ready to help me about the house: he fixed our string clock and could make shelves for us. My father died in 1963, and my mother died in 1967. They were buried in the 3rd Jewish cemetery.

Some time after finishing school my sisters got married. Rosa married Anatoliy Garyshev, Russian. She changed her surname and moved to Ilichevsk [port on the Black Sea, 25 km from Odessa, in 1973 became a city] where she worked as senior engineer in the department of capital construction. Her daughter Yulia lives in Odessa now with her husband Yuriy Vozovikov, Russian, and their 6-month-old son. Raisa married Vladimir Gordienko, Ukrainian. They also settled down in Ilichevsk where Raisa worked as an estimator at a plant. Their daughter Vika became a teacher. She is married and has a daughter. Her daughter's name is Irina. Raisa died in 1993 and was buried in Ilichevsk. My brother Samuel finished 7 forms and became a mechanic. My brother worked for the association of deaf and mute people and then made locks at the plant of household goods. He was married, but they divorced. They didn't have any children. In 1985 he fell ill and died suddenly on his way home. He was buried in the 3rd Jewish cemetery in Odessa.

Our daughter Tatiana went to a kindergarten and my wife and I worked. In 1970 we received a new two-bedroom apartment in Tairovo, a new district in Odessa. That's where we live now. Tatiana studied in a secondary school, and after finishing the 8th form she entered a medical school. We raised her with the understanding that her parents are Jewish and she is a Jew. She also knew that she could face problems, but she has a strong character. When she studied in her medical school something happened showing her attitude. There were a few Jews in her group. One of them was a weak 'Mom's sonny'. One of his fellow students always pestered him. Tatiana was a quiet girl, but once she came to the end of her tether and stood up for this boy. The offender gave her a rude reply. She complained about it to her friends living in her grandmother's apartment in Khvorostina Street. Those boys came to the school and were most likely convincing talking to the offender since he apologized to Tatiana and her fellow students began to reckon with her. She could stand up for herself. After finishing school she became an assistant doctor and went to work at the hospital and polyclinic. To our grievance, she died seven years ago in 1996.

When perestroika 17 began, I was skeptical about it, mainly due to the personality of Gorbachev 18. I've always thought he was a chatter box. He started talking never knowing what he was going to say at the end. It was impossible to understand him. Of course, he gave people an opportunity to earn money, open cooperatives, travel or move abroad. This was a good thing he did. I've always been positive about the idea of emigration. Many of our friends and relatives have moved abroad, but we waited till our daughter grew up and got a profession. When she died, we thought we didn't need emigration. When cooperatives began to operate I quit my shipyard and went to work at a cooperative that manufactured stone cutting machines. I was deputy chairman of this cooperative. Unfortunately, its chairman happened to be not very decent and I preferred to quit this job. Later my friend and I rented a boat repair shop. A boat repair shop is a sailing unit dealing in boat repairs. When my friend died I became director of this shop. In 2000 they terminated our rent agreement and took over the shop, but I worked there as a foreman for some time. In May 2000 I went to work as chief of productions of a private company in Odessa. They also dealt in boat repairs. regardless of a big difference in age I made friends with the owner of this company Yevgeniy Vitebskiy, a Jewish man. He and his parents began to involve me in the Jewish way of life. I worked there until late 2002 and then retired. My wife Alla retired in 1991.

Recently I've learned much about Jewish traditions. I've visited the synagogue in Osipova Street with Yevgeniy Vitebskiy several times. My family receives newspapers 'Shomrey Shabos' and 'Or Sameach' where I read a lot about the history and traditions of our people. I attend the Society of Jewish Culture and the community center. Now that I know more about traditions of our people, I begin to observe them. My wife and I try to do no work on Saturday and follow kashrut more closely. My wife and I receive food packages from the charity organization 'Gemilut Hesed'. Of course, life was morally easier before, when there was my family, everybody was living. My parents are long gone, so are my sister and brother, but the most terrible thing for my wife and me is that our daughter died.

Glossary