Henrich F.

Bratislava

Slovak Republic

Interviewer: Martin Flekenstein

Date of interview: May – June 2006

Family Background

My grandparents on my father’s side were from the town of Topolniky. In those days the town was named Nyarasd [the town’s Hungarian name of Nyarasd was changed to Topolniky in 1948. After 1989, two names are used for this village: Topolniky in Slovak as well as the Hungarian Nyarasd – Editor’s note]. My grandpa was named Heinrich F., and my grandmother Ema, née Blauova. My grandfather was a door-to-door salesman, who used to walk from village to village with a cart, and sell textiles. My grandmother died before I was born, likely of stomach ulcers. She underwent surgery in Bratislava, where she died of her illness. She’s buried in Bratislava, at the Orthodox cemetery.

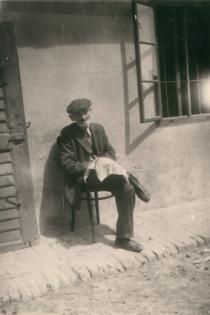

My grandfather was already in his golden years. I met him only a few times, because Dunajska Streda, to which Nyarasd belonged, was taken over by Hungary during the war 1. My grandfather, like his children too, was completely modern, including his observance of religious customs. The family observed mainly the holidays. During holidays they would visit the synagogue in Dunajska Streda. My grandfather didn’t survive the war.

I remember Nyarasd really only foggily. The last time I was there I was 3 years old, on the occasion of some relative’s birthday. The village roads were dusty. My grandfather’s house stood on this bit of higher ground. I don’t even on what occasion it was, that my parents left me with my grandfather for a few days, so that I could improve my Hungarian. Beside my grandfather’s place stood the house of the local reeve, who had a son that was older than I. There was an apple tree in the yard, and he often said to me that when an apple fell, I should call him. And I would yell out: “Jánoska, lepotyant az óma.” [in Hungarian dialect: Janoska, an apple fell. – Editor’s note]. That I remember. He’d come over and we’d eat the apple together.

My grandfather lived in a typical village house that had a front hall and part of the courtyard was roofed over. They didn’t have running water, but drew it from a well in the yard. In the front part of the house there was a store with various goods. You entered the store through the kitchen. Behind the kitchen there were two rooms, and in the back there was a stable. There was a small garden behind the house, and they also raised animals, but I don’t remember anymore which ones. After the territorial division, when Nyarasd fell to Hungary, I never met my grandfather again. He most likely died on the way to a concentration camp.

My grandparents, the F.s, had three children; the sons were named Alexander and Julius, and the daughter Berta. Berta married Mr. Deutsch, who came to live with them in Aunt Berta’s family home. After the wedding he took care of the store, and Aunt Berta was a housewife. She and her husband had four sons.

Uncle Alexander worked as the superintendent of a sugar refinery in Dioszeg, now called Sladkovicovo [the town’s Hungarian name of Dioszeg was changed to Sladkovicovo in 1938. Since 1989 two names have been used for this small town: Sladkovicovo in Slovak, and the Hungarian Dioszeg – Editor’s note]. They had one son, Herbert. During World War II, Herbert did munkaszolgálat 2 in Budapest, and later hid out on the grounds of the sugar refinery, where he survived the Holocaust. He died much later, in Bratislava. Uncle Alexander died before the deportations, in 1942, of natural causes.

We didn’t visit Uncle Alexander often, because Dioszeg was a part of Hungary 1. I actually remember only one visit. My uncle was the superintendent of a sugar refinery that belonged to the Kuffner family. There was a set of railway tracks that led into the sugar refinery, on which they transported sugar beets, and we arrived on those tracks when we came to see my uncle.

My mother’s family was from Bratislava. They were natives of Bratislava. My mother’s father, Filip Schwartz, died before I was born, and I only know him from stories I heard. He was a shoemaker. His workshop was in Zidovska ulica [Jewish Street]. He and my grandmother, Jolana, lived in Mikulasska Street. My grandfather loved fish. If you know Bratislava, there were pontoons by the old Rybne namestie [Fish Square] from which fishermen used to catch fish from the Danube. They’d sell their catch right there. Every single day, my grandfather would go for his fish, which he’d prepare and eat. That was his specialty. Otherwise I don’t know anything else about him.

Grandma Jolana was a seamstress. She sewed for clients, but also for her friends and family. Mainly for us, her grandchildren. She was a merry old soul, always smiling and in a good mood. As Grandpa had died, she lived in the apartment in Mikulasska Street alone. It was an apartment, with one room plus a kitchen. The apartment had electricity and running water.

She used to regularly visit all her daughters, who were six. I’ll begin with my mother. She was named Helena. Another daughter was Greta, married name Perlova. Then there was Zelma, who married Freundlich. Next was Bella, Rozalia, or Roza. Aunt Roza married Adolf Fischer. Fischer was a well-known typographer. He had a memorial plaque in the Pravda publishing house in Bratislava. Aunt Roza had two daughters, Edita and Lydia. Another of my mother’s sisters was Irena, married as Ehrenreichova. After her wedding she lived with her husband and children in the town of Sahy. Her children were named Stela and Richard.

As children, we saw our grandmother on a daily basis. Either we’d visit her, or she us. She lived in Mikulasska Street, and we in Venturska, where my parents had a store. While my parents were in the store, I was usually at Grandma’s. My grandmother didn’t dress differently from other people. She dressed in a worldly fashion, like most women. Grandma wasn’t religious. I remember that she’d occasionally buy a goose, and make soup from it. She’d prepare goose innards with tomato sauce, and bake barkhes. That I foggily remember, those were frequent Friday suppers. During the High Holidays, our whole family would go to the Neolog synagogue on Rybne Square. Bratislava had many prayer halls that were attended by Jews. But our family observed only the High Holidays. I can’t describe them, as I was still small. As children we didn’t really observe the fast during Yom Kippur [Yom Kippur: The Day of Atonement. The most celebrated event in the Jewish calendar. A day of “cleansing of sins”. Fasting is observed. – Editor’s note]. But I do remember Simchat Torah [Simchat Torah: the main significance of the holiday lies in the continuation of the Five Books of Moses. The cycle of reading from the Torah ends and begins on the same day, and the public celebration connected with this expresses the joy inspired by this process – Editor’s note], how we would walk, with stops, around Rybne Square, but that’s also a long time ago. I didn’t even have a bar mitzvah [bar mitzvah - “son of the Commandments”, a Jewish boy that has reached the age of thirteen. A ceremony, during which the boy is declared to be bar mitzvah, from this point on he must fulfill all commandments of the Torah – Editor’s note]. My 13th birthday took place during the war year of 1941, and by then people had other things to worry about.

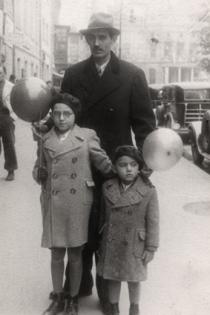

My father was born in Topolniky, at the time Nyarasd, on 25th November 1900. He finished mercantile school in Dunajska Streda, and then got a job in Bratislava. I don’t think that my father had any hobbies, besides our whole family regularly going on trips. Most often we’d go somewhere around Bratislava. For example Zelezna Studnicka [recreational town in the region around Bratislava – Editor’s note]. Several families would get together there. Walking around all morning wasn’t a problem. My parents’ friends were from various circles, they weren’t only Jews. But most often we were with my mother’s sisters and their families.

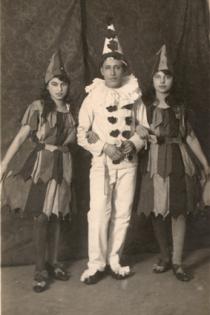

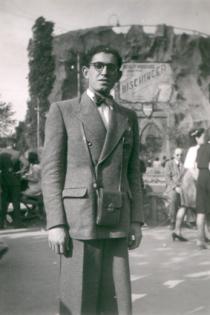

My parents met in Bratislava, during a St. Nicholas Day party. They were also married in Bratislava, on 27th February 1927. They definitely had a religious ceremony. My parents spoke several languages. They spoke German, Hungarian and also Slovak to each other. But with my father, Hungarian and German were dominant. My mother’s native tongue was probably German. But I don’t know that for sure. My parents’ style of dress didn’t differ from the people around them either, which is also documented by photographs from that time.

In 1918 my father entered the Czechoslovak Army, to do his army service. He ended up in Ruzomberk, as a hospital orderly. If I was to describe my father, I’d say he was a fantastic person. A truly good man. He was purposeful, of sound character, and punctual. He always managed to achieve what he wanted. There were never any disagreements between us. He was so tall, that he towered over everyone around him. He was around two meters tall. My mother was a good, respectable woman, and an excellent companion.

Our first home was in Lazaretska Street. Among our neighbors was the Burian family, who weren’t Jews. The Burians had three daughters, who used to play with me when I was a little tyke. At that time I might have been about one year old. I still remember like it was today, Mrs. Burianova washing the stairs and courtyard gallery. She had a pail of water, and I kept tottering around it, until finally I fell into it headfirst; since that time I avoid pails. That’s one of my memories. Mr. Burian was a butcher. He’d had diphtheria or something similar, and had a tube sticking out of this trachea [windpipe]. When he talked, he always had to plug it. This friendship from Lazaretska Street lasted even after we moved away from there, up to the year 1942. By that time the girls were already married off. One of them had by coincidence married a butcher, the same profession as her father. They had a butcher’s shop in Dlha Street, today it’s Panska. When meat was being rationed during the time of the Slovak State 3, they’d always give us a bit extra. This lasted up until 1942; what happened to them after that, I don’t know.

Our apartment in Lazaretska Street consisted of a kitchen plus one room, and you entered it from the courtyard gallery. The toilets were in the hall, shared with all the residents on that floor. But there was already running water and electricity. From there we moved to Zizkova Street. It was in a neighborhood named Zuckermandel. Our move was related to my father’s work. At that time my father was working in Dlha Street, today Panska Street. So we moved closer to his workplace. At that time I was about 3 or 4 years old. We lived on the first floor. From the hallway we had a view straight out onto the castle cliffs. There was also a pile of kids in the neighborhood.

After the war, they gradually tore down all of Zuckermandel. A lot of Germans and Jews lived in this quarter. There were fishermen there, who had their pontoons on the Danube, where they caught and sold fish. Tradesmen also lived there. For example, right across from us was a stonemasonry that belonged to Bernat Löwinger, Grandma Jolana’s brother. Grandma had seven siblings. Most of them lived in Bratislava, close to each other. Her brother Bernat was a stonemason. He made gravestones for the Jewish cemetery. Her second brother was Illes, who lived in Nitra, where he had a furniture factory. During the war we hid out at his place for some time, but I’ll get back to that. The third brother was Jakub, an upholsterer. He had an upholstery workshop in Mickiewitzova Street. Next was her sister Regina, who had a hat store, and made hats. She lived right across from grandma Jolana, in Mikulasska Street. Then there was Roza [Rozalia]. She had a store on today’s Namesti SNP [SNP Square]. Then there was Mozes, who was also a stonemason, and had a workshop in Venturska Street. Later we also moved to this street. The last was Juliska, who also had a hat manufacture in Klariska Street.

As little children, we ran around the town and during our wanderings we would always run in to see one of our relatives. I might have been about 10 years old at the time. I remember that we used to go see Aunt Juliska and watch hats being made. Pieces of felt cloth would be stretched over forms, making various styles. Aunt Juliska survived the war, and moved away to Israel. We’d always also run in to see another of Grandma’s sisters, Regina. Eventually, she lived right across from Grandma. Regina was deported during the war, and probably died in a concentration camp. At Bernat’s we’d wander around the stonemasonry and watch him carve letters. Mozes was also a stonemason, and because he lived across from us, we also visited him often. We’d amuse ourselves by painting ourselves with gold paint that he used to paint the letters on tombstones. Bernat and Mozes were deported and died in a concentration camp. During the war we visited Illes, who lived in Nitra. My brother, grandmother and I hid out in the courtyard that was next door to his furniture factory. Illes was also deported. After the war, Jakub returned and emigrated to Australia. So that’s the entire family tree on my grandmother’s side.

I don’t remember my grandfather Filip Schwartz’s siblings, and neither do I know anything about the siblings of my paternal grandparents. I knew only these ones on my mother’s side, because I saw them often.

We’ve already talked about the fact that my father had studied in Dunajska Streda; my mother studied to be a sales clerk and merchant, in Bratislava. Before my parents had gotten together at the aforementioned St. Nicholas Day party, they had already been colleagues from work, at the Kurtz Company. My mother worked in a store, and my father worked as a traveling salesman. In 1934, as a result of the depression 4, one store after another was going under. The Kurtz Company ended up the same way. My father then opened his own clothing store in Venturska Street. He sold notions, buttons and accessories for tailors. Later he sold underwear as well. He and my mother worked in the store together. Thanks to the business we weren’t poor; we lived fairly well.

In 1934 we moved from Zuckermandel to Vidrica, where we lived on the first floor. My parents got to know our neighbor, Mr. Trojan, who had a barbershop in Dlha Street. Underneath our apartment there was a butcher shop. We had a wooden floor made of beams that had holes in them, and through them we could see into that shop. It was only this temporary apartment for us. Then another apartment became available, right above my father’s store, where we then moved. Count Bilot had lived in that apartment before us. He moved somewhere, and handed the apartment over to us.

Growing Up

I was born, as my parents’ first child, in 1928. They named me Henrich, or informally Harry. Several years later, on 28th February 1935, my brother, Siegfrid, was born. My brother and I got along very well. He was an agreeable kid. But we didn’t get to enjoy very much fun and games outside, because the anti-Jewish laws 5 began coming out, so we mostly stayed inside.

When I was very young, my parents registered me in nursery school. I don’t remember much from this time either. The nursery school was in Venturska Street. Tante [Aunt] Ruth was in charge of us. We used to go to nursery school with these little baskets that hung from our necks, which contained our snack for teatime. We used to play with plasticine, and I hid a piece of it in that basket. Later, when I was hungry, instead of bread I took a bite of the plasticine. Those are the tiny little pearls hidden in the human brain.

Besides that, Grandma Jolana used to watch over us a lot. Actually, she watched over all her grandchildren. We’d walk with her to the park in Hviezdoslav Square, to the Janek Kral Orchard. We’d take a ferry across the Danube, and there was this huge park there, where we’d play. Besides this, we also used to go for walks with her around Bratislava. We used to go out into the country with our parents. In those days vacations weren’t much in fashion. Mostly we’d go out into the countryside around Bratislava. In the summer my parents would send me to rest homes. These were pensions that took children on recommendation. There we’d play games together and walk around in the vicinity.

We kept in closest contact with that part of the family that lived in Bratislava. When cafés, cinemas and theaters were already forbidden, a large part of the family and friends would then also get together at our place. They’d play cards, mainly Marias [Marias: a card game originating in Bohemia played with the Czech 32-card German suited pack – Editor’s note]. As far as we children are concerned, Aunt Roza lived the closest, practically around the corner. We used to go to her place almost every day. Auntie had two daughters, Edita and Lydia. Edita was born the same year as me, so 1928, and Lydia was born in 1935, like my brother. They deported their entire family. Only Edita, who went on the same transport as my parents, survived the war. She returned from the Auschwitz concentration camp.

We also used to go visit my mother’s sister Bella. She didn’t have children. She worked in a clothing shop. We also used to go to Aunt Zelma’s, who had two daughters. One of them was named Erika; I don’t remember the second name. They had the luck to move to the Palestine in 1938. My mother’s sister Greta lived with her husband, Perl, who was a typographer. They had two children, a son named Tibor, and a daughter, Olina. They lived on Dunajska [Danube] Street They deported them all. My cousin Tibor got to Bergen-Belsen, where he luckily survived the war. My mother’s sister Greta was also lucky, she survived the concentration camp. My mother’s last sister was Irena Ehrenreichova, who lived in Sahy after getting married. She had two children, Stela and Richard. Except for her husband, they all died during the war. He remarried, and then died of a heart attack. His second wife emigrated to Israel.

I started attending people’s school 6 in 1935. The school building stood at Zochova Street No. 3. I went there until Grade 5. Then the year 1940 came, and they nationalized the school. I was supposed to go to council school, and here’s where the first jolt and turning point in our lives came. Jews weren’t desired students in state schools, even though from a religious standpoint our family our family was quite far removed from Judaism. Our family was modern; we didn’t feel anything major towards religion. Everyone could feel that something dangerous was approaching, and that it was very close. The period of baptisms arrived. With a certificate from the parish office, I was accepted at the First State Council School at 3 Zochova Street. At the same school where I’d already been for five years. I also had godparents, who were supposed to protect us. But it didn’t help very much, because we were still obliged to wear a yellow star 7. I dealt with this problem in such a way, that instead of a permanently sewed-on star, I had it on snaps. In case of danger, I could remove it, and show my ID, that I’m a student from a state school. Unpleasant, especially for me, were morning prayers, catechism and defense classes, where we’d march around singing: Friends Stand on Guard!, We’re Native Slovaks and similar things. Already at that time things were coalescing towards the People’s regime 8. Apprehension settled upon us when our teachers began appearing in uniforms of the Hlinka Guard 9 or those of officers of the Hlinka Youth [Hlinka Youth: The Hlinka Guard 9 founded youth groups and helped organize their activities. These groups were named Hlinka Youth – Editor’s note]. In the morning we’d greet each other at the school with the People’s greeting, On Guard! Can you imagine how a person felt when he went to school?

During that time, I personally lived in constant fear, because at this school they had severe corporal punishment. For example, we had this teacher that was named Macko. He was from Liptovsky Mikulas. He had a hand like a lumberjack, when he gave someone a slap, it spun him around like a top. His slaps were a common thing. Another teacher had a switch, another a ruler. They’d either beat us with that, or their hands. Another would yank our hair. We were physically punished for every stupid little thing. For example when we threw a sponge, basically for everything... I have a slap from Macko engraved in my memory. After that I tried to avoid being punished in any way I could. I was on my best behavior.

Before the war we had both Jewish and non-Jewish friends. But the anti-Jewish laws had a big influence on mixed friendships. It began with the fact that customers stopped coming to my father’s store. They began saying that they won’t buy things from Jews. You know, you eventually notice that. Friends turned away, from one hour to the next, they stopped talking to us. It very much affected us children. Good thing that my cousin Edita lived nearby, in Dlha Street. We used to go play at their place. But mostly we were at home, because the prohibitions limited us to the degree that you almost couldn’t go out into the street. When we did go out into the street, German boys would start chasing us.

As a native of Bratislava, I knew all the little streets, passages and nooks and crannies of the city. I knew Zidovska Street, Klariska, Kapucinska... So I knew that if in Klariska I enter a certain building and crossed two courtyard galleries, I’d get to Kapucinska. Or if I entered in Kapucinska, I’d exit into Zidovska. We knew routes through attics and cellars. Sometimes that saved us from those German boys. So, when the Hitlerjugend 10 would begin chasing us, we’d run into a gateway, and through a courtyard gallery we’d get to the next street. It basically saved us from a certain beating.

Beginning of the War

Sometime in 1939, NSDAP [Die Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or Nazi Party] and Hitlerjugend headquarters were set up on the corner of Venturska Street, where we were living at the time. The headquarters of the Hlinka Guard were located in the building of today’s University library, not far from the Michalska Gate, and the Hlinka Youth, which regularly met in the evenings, was also there. Their drums and horns thundered through the streets of Bratislava. All you heard was boom, boom, boom, the Hitlerjugend was marching. Boom, boom, boom, the Hlinka Youth was marching. They sang songs and shouted. They for example sang Kamarati Na Straz! [Friends, On Guard!]. Like Slovenska Pospolitost 11 does today. They marched around with their arms in the air. Then they smashed windows and storefronts. They carried daggers with them. After dispersing, it ended with them catching someone and stabbing them with one of those daggers, or beating them to death. That’s why we used to run away from them over those courtyard galleries.

Slowly it happened that my father’s good, old customers stopped coming to the store. Then came vile graffiti, swastikas and Jewish stars that were painted on stores. We also had our shutters painted many times. That’s how it slowly started, until many friends turned away as well. Luckily not everyone renounced us. There were also people that helped. At the beginning I already mentioned the butcher, Mr. Burian, and his brother-in-law. Mr. Dobos, who had a bakery, also helped us. So we always had a bit more bread and meat than others. But gradually even these connections stopped working. Because even these people also gradually had less and less. Finally, in 1942, one woman from Vienna, Karolina D., who wanted to have a store too, came to see us. She told my father to give her the keys and cash register, that she’s the new owner of the store. She was our Aryanizer [Aryanization: the transfer of Jewish stores, companies, factories, etc. into the ownership of another person (the Aryanizer) – Editor’s note]. Subsequently they put us in the Patronka collection camp. Luckily the Aryanizer didn’t know how to run the store, and arranged for us to return from there. My father worked in the store, because she didn’t know how to order goods. As I’ve already mentioned, Karolina D. was from Vienna, and was only staying in Bratislava.

Father got some sort of exception 12. There was a huge number of exceptions. According to me, there might have been at least fifty kinds. In the morning a yellow ID card was valid, by evening it was a green one, then a white one, then there was a seal from the Hlinka Guard, from the ministry, the president... So that what was valid in the morning, they didn’t have to accept in the evening. You had to pay for everything, of course. It was extortion.

Around the same time that we lost the store, they also took the beautiful apartment that was above it away from us. One day a certain doctor arrived, and pointed out that Jews can’t have an apartment with a view out on the street, especially when the Hlinka Guard and Hitlerjugend were marching there. He told us to kindly leave the apartment. It was a truly beautifully appointed three-room apartment in the center of Bratislava. They moved us into a space that had previously been occupied by the Hashomer Hatzair movement 13, which had already been banned. Where we lived had most likely been a warehouse before. It had no floor. Father had a plank floor put in. One large room was divided into two. So we had a “bedroom” and a kitchen. Leading to these rooms was a hallway about 15 meters long and one meter wide. It was isolated from the outside world. An ideal place for people that were working for the underground. For example, at our place the escape of Jews to the Palestine was planned, by boat down the Danube...

Relationships in our family were always on the level. Our parents always told us what was happening. For example, I knew how much our father made in the store, I knew about his relationship with the Aryanizer. We knew what the political situation was. Many people and family members used to come to our place. They played cards and at the same time discussed politics. Actually, we knew about everything. My two uncles, Perl and Fischer, worked in typography, as typesetters. They worked for the underground. They printed flyers and various exhortations against the regime. My father wrapped goods in these flyers. So besides persecuting us for being Jews, they were also after us because of this.

These people met at our place daily. Practically every day we also experienced banging at the door, kicking at the door accompanied by loud shouting. The Guardists were arriving. Our visitors would be sitting at the table playing cards, and the Guardists would say: “Do you know that you’re not supposed to be meeting?” Well, then they’d have a shot, take an envelope and leave. But they were insatiable. It would happen that they’d even come more than once a day. If there was an arrest warrant out on someone present, they’d take him with them for interrogation. Those were perilous times.

In Hiding

When it was already very bad, our parents would always send us to safer places. They tried to save the second generation; we traveled from one place to another. I also got into a sanatorium for lung diseases in Kvetnica. At that time, my brother was at home with our parents. Working in Kvetnica was Dr. Kohn, who concealed many “ill” Jews there.

Upon our return from Kvetnica, my brother and I left with Grandma Jolana for Nitra. Grandma’s brother Illes, who had a furniture company, lived in Nitra. This company’s courtyard was next door to the courtyard belonging to the company Vychterle & Kovarik, which sold tractors, threshers and similar farm machinery. They had one long building. In the front there was a showroom and offices. In the back there were company apartments for the employees. We rented one of those apartments, and hid our there for some time. Then we returned to Bratislava, where it was also dangerous, and so our parents sent us to a Protestant youth camp in Brezova pod Bradlom. Usually one went there for two-week stays, but we were allowed to stay there for two months. I’m sure there were other Jewish children among us.

After we returned from the camp, our parents sent us to some farmer in Devinska Nova Ves. We were in hiding there for only a few days. From there, they sent us to northern Slovakia for the summer. We left Bratislava by train for Liptovsky Hradek. There some lady was waiting for us. We got on a farm wagon with hay, and she drove up to a game warden’s cabin in Vychodna. I don’t remember us paying for anything. But we didn’t last very long there, either. The couple that was taking care of us had a son who worked in Svit during the week, and had gotten involved in various schemes, and of course also with the Slovak National Uprising 14. They began to have problems, and in fear that they’d be raided, they put us on a train and sent us to Bratislava. It was the last train that passed through the tunnel in Vrutky. They then blew the tunnel up. So we had at least that bit of luck. At home things were heating up. They were grabbing people every day, and deportations were taking place. By then our parents weren’t safe either. My father was still working in his former store that they’d Aryanized.

In the past, my father had often done business with Romanian boatsmen. They used to buy fashion goods in the store, and he’d made friends with them. He also got to know a few customs officials, and other people from the harbor. So it was also thanks to them, that we knew people at the Bratislava harbor. In those days there used to be pontoon piers in the harbor, on which were dwelling units that people lived in. Steamboats used to anchor by these pontoons, and would stock up on coal and water. Father found a place for us and our mother with a friend of his on coal pontoon No. 3, where the Zatko family lived. The coal pontoons floated on the water on two hollow cylinders. When things got bad, we crawled in one of those hollow cylinders. It didn’t take long for someone to inform on them, that they were hiding us. We had to leave there in a hurry. My mother and brother went home, and I went to another of my parents’ friends. His name was V.

As I later learned, that night there was a big roundup. My whole family, my father, mother, brother, grandma Jolana, along with the Fischers, they rounded them all up, only I remained free. Mr. V., who concealed me that night, was a taxi driver. He lived across from us in Venturska Street. He contacted Mr. B., who had a gas station at the corner of Palackeho and Jesenskeho streets, to send me to some family in Podunajske Biskupice. I took a bus from Safarik Square to the end of the line in Prievoz. Waiting for me there was a boy who addressed me by my name. He told me to come with him. I stood on the back axle bolts of his bicycle, and he took me to [Podunajske] Biskupice. The family I had arrived at was named Pagac. I was only supposed to stay with them for a few days. In the meantime, however, deportations had taken place, and I found myself completely alone. What were they supposed to do? They didn’t want to throw me out, so I stayed with them. All I had was one set of summer clothes, shoes and a windbreaker.

The Pagac family rented a two and a half room house. The husband and wife, three sons and an 80-year-old granny lived in one and a half rooms and the kitchen. The second, large room belonged to the owner of the house, and was locked. The lady that owned the house was abroad for an extended period. Mr. Pagac was a jack-of-all-trades. He was a driver, a locksmith, he could repair and manufacture machines. Mrs. Pagacova was a very kind woman. She was from Budapest. The oldest of the sons was named Karol, then there was Tibor, and the youngest was Lacko [Ladislav]. They accepted me as their fourth son, with the difference that no one could know, see or hear anything about me. This principle became law, and was strictly adhered to. At that time the youngest, Lacko, was only about 3 years old. His words became unforgettable for me. Instead of airplane he used the word angidádo, and his other words were ‘tüjn el’ [Hungarian: get lost, disappear]. Always, when there was someone nearby, he shouted to me: “Tüjn el!”

At night I slept on a haystack at a nearby farm. During the day I’d be behind some clutter up in the attic, or in the cellar. The stairs to both places were camouflaged. This went on until the first frosts struck. The haystack kept shrinking, until it didn’t provide a safe hiding place and a feeling of security. I caught a cold. Calling a doctor was impossible, so they found me some medicine. Despite this, there were complications. I got inflamed joints, and couldn’t move. I lay paralyzed in granny’s bed, who soon after died. When people were paying their last respects, and during the wake, they moved me up to the attic and covered me with old blankets and sacks. I was there until the last relatives from Bratislava and Hungary left, who also spent the night there. After granny’s funeral, they carried me down onto her bed, but the state of my health kept getting worse. They called Mr. B. over, to consult with him what they should do if I died. Through his friends, Mr. B. got a hold of some salves and salicylate [salicylate: salicylic acid, effective primarily against fevers, and partly against pain – Editor’s note], which slowly put me back on my feet.

Outside it was freezing, in the attic and cellar it was cold. Ujo [Uncle] Pagac thought of another hiding place. In his and his wife’s bed, between the springs on which the mattress sat and the B.m part of the bed, which stood on planks, he made this drawer. It was made so that I could crawl into it in case of great danger. The smallest munchkin in the family tested it out by yelling “tüjn el”, and I then crawled under the bed and into the drawer. The drawer enabled you to lie horizontally in such a way that when someone looked under the bed, he didn’t see anyone, and neither could you see anyone when the bedclothes were stripped off. During the day I stayed mainly in the attic, and at night I preferred to make the journey down to the cellar, which was behind a camouflaged door. In those days house searches were a daily matter.

The house where the Pagac family lived stood at the intersection of two main streets leading to the train station. If you know Podunajske Biskupice, today they sell good ice cream there. At that time they were loading material for the German army at the train station. On orders of the SS high command, the commander of counter-intelligence was moved into that half-room where before granny had lived, and I during my illness. I don’t know what his name was, but he had a lot of medals and various crosses. No one had foreseen such an event. Luckily he was often away from the house, even for several days at a time. So we lived “harmoniously” side by side, or more exactly one above the other, from Christmas 1944 until April 1945. It was a matter of life and death. No one can describe my anxiety, and Mr. Pagac’s fear for his family. In those days, they shot people for such infractions. To banish my nervousness and anxiety, I darned by candlelight, day and night, the socks of all Pagac family members far and wide. I also copied recipes that Mrs. Pagacova had very many of. This time passed. Once Mrs. Pagacova proclaimed that when the war ended and if we survived, she’d adopt me.

You could already hear the booming of cannons in the distance. The traffic in the streets grew denser. The Germans were on the move, they were arrogant, aggressive and there were very many of them. One day, in the early hours of the morning, the commander came home all muddy. He packed his things. Through the closed door I heard him say: “Soon the weather will be nicer.” He saluted, and without a word of thanks sat into his staff car and was seen no more. At night mortar fire, which had already been nearing for several days, began. Mortar rounds were falling around the house, and I counted them out of boredom. In the morning the firing slowly tapered off. Only here and there, a machine gun sounded. From a window in the roof, I could see the first Russian soldiers. One was pushing a bicycle, the second even had two of them, and he had a machine gun on his shoulder. A beautiful feeling enveloped me - I was saved. Even today, it still brings a lump to my throat. I carefully came down from the attic, so I could tell everyone what I’d seen. After hesitating for a long time, I decided to be the first one to walk out into the courtyard, into the sun, into the garden. At that moment, a Russian soldier rang the bell at the gate. To this day, I still remember our brief conversation:

“Any Germans?”

“Nyet [No]” I answered, with my knowledge of the Russian language from my school days.

“Any women?”

“Nyet”

“Any vodka?”

“Vodka nyet, water yes.”

“What time is it?” I drew up the sleeve of my only windbreaker that I had, and said:

“Ten o’clock.”

“Give it here!”

That watch was my only property. So, I paid the price for my liberation.

After the War

Today I don’t exactly know if it was before, or after the May 1st celebrations in 1945 that a tall, badly dressed man with a huge head rang at the gate. He had a shaved head, sad eyes and was very skinny. He asked whether the Pagac family lived there. I said that yes, they did. At that point he said my name, Harry. I recognized that it was my father, who I hadn’t seen for a long time. We fell into each other’s arms and cried together. He told us about what had happened when my mother and brother had returned from the harbor, how they’d deported them to Birkenau, how they’d separated them and led them off to the “showers”.

My father was in truly horrible condition. Two meters tall, he weighed only 45 kilos [6’ 6.5” and 99 lbs.]. In Poland he’d ended up in a coal mine. The conditions there had been horrendous. They worked in inhuman conditions, and suffered from hunger. When they were very hungry, they ate coal dust, so that they’d have something in their stomachs. That same dust also got into their lungs. He had open sores from the wooden shoes they wore. When the front was approaching, they rounded them all up from the surrounding camps onto a march 15 into the interior. They marched, hungry and exhausted. Those that died were left where they fell. The Germans were always asking those that couldn’t go on anymore to stand aside. My father stood aside, along with another about 90 fellow prisoners. They were mostly from Bratislava, and were keeping together. They didn’t shoot them on the spot, but loaded them onto a truck and drove them back to Birkenau; when they unloaded them from the truck, the Russians started firing. The Germans took fright, ran away and left them there, and so they were liberated by the Russian army. From there, together with the others that had been saved, he set out for home. They went by train, hitchhiked, and on foot. He returned home in a roundabout fashion. From Poland, through Kosice and Budapest, to Bratislava. He was spurred on by the desire to find me, as he knew that I hadn’t been in a transport.

The Pagac family didn’t want anything for concealing me and risking their lives. On the contrary, if my father wouldn’t have returned, they were intent on adopting me. We remained in a very close, literally family relationship with them. We visited and brought them gifts at every opportunity, to show our great thanks. We lost contact with them in 1968, when they left for Germany to be with their children. Their sons had already emigrated earlier on.

My father and I returned to our apartment. We of course didn’t find anything there, only a pile of family photographs. They were stored in a box in the attic. Besides this, we also found some documents. We saw our furniture at our neighbor’s place, but nothing could be done about that. As far as the store goes, we got it back, along with permission to once again operate it. However, there was also nothing left in it, besides one lamp sticking out of the ceiling. The shelves were completely bare. Unfortunately, not long after, they nationalized our business 16.

After our store was nationalized, my father worked for Vesna [Vesna: a chain of textile outlets offering a wide assortment of textile goods – Editor’s note]; they then renamed it to Otex [Otex: textile company offering a wide assortment of men’s and women’s clothing – Editor’s note]. There he somehow didn’t get along with the management, and so he left to work at the Tuberculosis Research Institute. He was in charge of the warehouse and materials and equipment. Unfortunately, the concentration camp had left its deep marks on him. His lungs were full of coal dust, and this caused complications, to which he succumbed in 1964.

My cousin Herbert F. also survived the war. Herbert’s father and mine were brothers. Uncle Alexander had already died before the deportations. In his honor, Herbert also took on his father’s name. So he was named Herbert Alexander F.. Before the war, Herbert lived in that part of Czechoslovakia that then fell to Hungary. He ended up doing munkaszolgalát. After the war, he worked in a sugar refinery, in Dioszeg, where he lived in a company apartment, in a mansion. Soon after they had to give up that apartment, and got a replacement apartment in the town of Nebojsa, by Galanta. That was sometime at the beginning of the 1950s. Herbert married a Christian girl. He graduated from university in the field of pomiculture [fruit growing], gardening and the breeding of fruit trees. Because he was an expert, he ended up in Prievidze around the middle of the 1950s, where he started up a pomiculture breeding station. At that time he was also working as a correspondent of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Near the end of his life, he moved to Bratislava with his wife and daughter, who had in the meantime been born. There Herbert worked at the Agriculture Commission. From there he went into retirement. Unfortunately he’s since died, here in Bratislava.

Because we had lost our apartment in Venturska Street during the war, we applied for a replacement. At that time you could even be granted a villa left behind by Germans that had been expelled 17. But my father was careful. He claimed that those Germans would return, and would ask for their property back. Today’s restitutions [Restitutions: law regarding the return of property – Editor’s note] confirm his words. So we got a small apartment on Hviezdoslav Square. You couldn’t even call it an apartment. There were two small rooms and a kitchen. In 1964 I got married, and my wife and I moved to [the neighborhood of] Kramare, to our current apartment.

After the war, a social group formed, where Jewish youth used to meet. We met each week for “tea”, at the Carlton [Carlton: one of the oldest and most luxurious hotels in Slovakia – Editor’s note]. We’d occupy the entire hall, buy ten raspberry sodas, dance, and then leave. There were both girls and boys there. That’s where people got together. But I didn’t last long in any relationship with a girl. I was mostly abroad, working. In those days I met one girl, through my cousin Herbert. Miss S., who they called Csöpi, who worked at an orthodontic clinic, on Kozia Street. She was a very pretty girl. But she was pretentious. Back then it was in fashion to go out with doctors and lawyers. So we split up. In 1963, someone mentioned a S. at some get-together, whether I’d like to meet up with her, so I said, why not. Back then, the way it was in Jewish society was that people met through friends and acquaintances. When I saw her, I said, hello Csöpi. The reply was: “I’m not Csöpi, I’m Eva.’ It was her sister. Csöpi had in the meantime gotten married. Eva and I met in January, in the Iskra Café, and in March we already had our engagement party. Right after, still that same month, we also had our wedding.

Our wedding was a Jewish one. The Bratislava rabbi, Katz, married us in the courtyard of the apartment building in Nesporova Street, where he lived. There weren’t very many people there. We had dinner in the Jewish kitchen, there where Chez David [Chez David: pension and the only Jewish restaurant in Slovakia, opened in 1993. It was kosher, but due to a lack of interest, today they no longer have a kosher menu – Editor’s note] is now. The wedding banquet wasn’t very large, because it was during Passover [During Passover, the consumption of many types of foods is forbidden, which is why the selection of foods was limited during the wedding banquet – Editor’s note]. Mrs. Schönefeldova was in charge of the kitchen. Then we also had a civil wedding.

My wife’s maiden name was Eva S. She was born on 27th January 1934 near Lucenec. Her mother was originally from Sahy. Her father worked as a superintendent on various properties, and so they moved a lot. Before the war, he was working as an adjunct on properties belonging to the nobleman C., in Liptovsky Mikulas. They were gathering Jews in the schoolyard, for transport. As they were standing there, they saw a vehicle in which C. was arriving. He spoke to the transport commander. He told him that her father is an economically important Jew, and that that type of person wasn’t allowed to be deported. They were fortunate that he managed to get them off the transport. Her father then continued working for him, and her mother did handiwork. My wife used to tell me that even at 2:00 a.m., she’d be darning things, so that they would at least scrape by. At that time, her father’s salary was 250 Slovak crowns [The value of one Slovak crown during the time of the Slovak State (1939 – 1945) equaled 31.21 mg of pure gold. The rate of exchange of the German mark against the Slovak crown was artificially set at 1:11 – Editor’s note]. They were living not far from Liptovsky Mikulas, in Vrbica. Later, they hid out in the mountains around Liptovsky Mikulas until liberation. The entire family survived, the parents and three children.

After the war, her father worked as a superintendent of farm properties, in Nebojsa, by Galante, in Jatov, near Nove Zamky, and finally in Geni, near Levicie. But the Jewish community in Levicie was falling apart. There were always less and less people. My wife’s mother was a very religious woman, and wanted to continue to lead a traditional, religious life. That’s why they decided to move to Bratislava. My wife’s family was exceptional in their observance of religious regulations. Her mother was very religious. My wife is a faint copy, as far as religious life is concerned. To this day, we still observe the Sabbath, light candles, and my wife prays. Her mother paid great heed to these rituals, virtually to the last moments of her life. Then, when she became very ill, she eased off of these principles, but still kept on observing all holidays. She kept a kosher household 18. Even after the war, my wife’s family had poultry slaughtered for them, just so everything would be kosher. When she was of an advanced age, she was in a nursing home, where she also died.

After my mother was pronounced missing, my father met Mrs. Haarova, and in 1946 they got married. Just like my mother, her husband had also died in a concentration camp. In our family we used to call her Manci. She and my father had met in a store. She was a seamstress, and had a large fashion shop. She employed about twenty people. They used to make made-to-measure underwear. During the time of the Slovak State, she even used to sew shirts for Tiso 19. Because in the post-war period it was hard to find buttons, thread and similar goods, she used to come to our store to shop. So they met and got married.

My stepmother, Manci, was one of seven children. Four of them survived the war. Manci was in a concentration camp together with her sister Ester. Ester married Mr. F. They’ve got a daughter, Ema. But Ester was very traumatized by her time in the camps, she had a nervous breakdown and died. Mr. F. also nearly died. He suffered from serious diabetes. Ema finished university and moved from Nitra to Bratislava. There, she got an apartment with gas heating. Unfortunately, she didn’t live to an advanced age either, she ended up poisoning herself with the gas. Ernest and Hugo were my stepmother’s brothers that had survived. After the war, Hugo lived in Switzerland, in Zurich. He had a daughter named Frida. Frida lived in Sant Polten, was a heavy smoker, and died very young. The last of my stepmother’s siblings that survived was Ernest. Ernest moved to Israel after the war.

Both my wife and I got along very well with Manci. Our family relationship that from a young age we had been brought up in, still before the war, also transferred itself to this one. Everything was honest. After my father’s death, he died in 1964, we continued to have good relations with Manci. She was very cosmopolitan. She traveled even during the times no one could. She even managed to arrange things with the police. She was a small, delicate, charming blonde. She also dressed very well. In short, she had good taste. My wife claims that she was the best mother-in-law, because she was always several hundreds of kilometers away [this comment was made with a smile and meant as a joke – Editor’s note]. We were really very good friends with her.

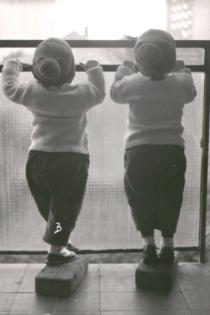

As I’ve already said, after our wedding my wife and I moved to a new apartment. Slowly, we furnished it. Slowly we improved it here, until it was livable. Then we could finally think about starting a family. On 26th August 1965, our sons, were born. Right up to the last moment we didn’t know that they were going to be twins. Back then they didn’t have ultrasound, only X-rays, but those we refused. When she was ready to deliver, I took my wife to the hospital. There she was being taken care of our friend, Dr. Pakan, the head doctor. He was a very sympathetic man. For a long time nothing was happening, and so my wife got an injection to induce labor. I was waiting downstairs in the lobby. Back then, you weren’t allowed to go up to the maternity ward. Suddenly the phone at the security desk rang. It was the doctor: “Mr. F., congratulations. You have a daughter on the way.” A little while later, the phone rang again: “Actually, it’s not a girl, but a boy, and quite cute. Congratulations... but wait a bit...” and hung up. A little while later he called: “Cross my heart, there’s another one there.” After the delivery he asked me: “Tell me, how did you do it?” “Dr. Pakan, with carbon paper.” Back then that was this saying, that twins were made with carbon paper. I took them home. We quickly bought one more baby bed. We exchanged the baby carriage, and then we commenced their upbringing.

When they were 6, I introduced them to the violin. My reason was that I wanted them to do something. Back then there were many children who were just running around outside, romping about, and doing all sorts of bad things out of boredom. So we said to ourselves that we needed to occupy them somehow. We bought them little violins. Because my workplace wasn’t far from a music school, I would walk to work each day with two little violins under my arm. After school was out, the boys would come for their violins and run over to the music school. So in this fashion they played up until Grade 5. Back then they said to themselves that they’d end with it. The violins were just lying around here. At that time I was working in Prague. I was walking by some publishing house, and I brought them all sorts of notes to folk songs. I put them on the table at home, and just like that, one of them took the notes, put them on a music stand, and began to play.

They liked the folk songs more than those prescribed fiddle exercises. So they began to play again. At that time the Bratislava Children’s and Youth Symphony Orchestra was being formed, where they were invited to come and play. They traveled through half of Europe with this orchestra, and were successful. For example, they brought home first prize from Holland. As time passed, they got into university, where they joined the folklore ensemble Technik, with which they then continued touring around Europe.

Glossary:

1 First Vienna Decision

On 2nd November 1938 a German-Italian international committee in Vienna obliged Czechoslovakia to surrender much of the southern Slovakian territories that were inhabited mainly by Hungarians. The cities of Kassa (Kosice), Komarom (Komarno), Ersekujvar (Nove Zamky), Ungvar (Uzhorod) and Munkacs (Mukacevo), all in all 11.927 km² of land, and a population of 1.6 million people became part of Hungary. According to the Hungarian census in 1941 84% of the people in the annexed lands were Hungarian-speaking.2 Forced Labor in Hungary

Under the 1939 II. Law 230, those deemed unfit for military service were required to complete 'public interest work service'. After the implementation of the second anti-Jewish Law within the military, the military arranged 'special work battalions' for those Jews, who were not called up for armed service. With the entry into northern Transylvania (August 1940), those of Jewish origin who had begun, and were now finishing, their military service were directed to the work battalions. The 2870/1941 HM order unified the arrangement, saying that the Jews are to fulfill military obligations in the support units of the national guard. In the summer of 1942, thousands of Jews were recruited to labor battalions with the Hungarian troops going to the Soviet front. Some 50,000 in labor battalions went with the Second Hungarian Army to the Eastern Front – of these, only 6-7000 returned.3 Slovak State (1939-1945)

Czechoslovakia, which was created after the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, lasted until it was broken up by the Munich Pact of 1938; Slovakia became a separate (autonomous) republic on 6th October 1938 with Jozef Tiso as Slovak PM. Becoming suspicious of the Slovakian moves to gain independence, the Prague government applied martial law and deposed Tiso at the beginning of March 1939, replacing him with Karol Sidor. Slovakian personalities appealed to Hitler, who used this appeal as a pretext for making Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia a German protectorate. On 14th March 1939 the Slovak Diet declared the independence of Slovakia, which in fact was a nominal one, tightly controlled by Nazi Germany.4 Great depression

At the end of October 1929, there were worrying signs on the New York Stock Exchange in the securities market. On the 24th of October ('Black Thursday'), people began selling off stocks in a panic from the price drops of the previous days - the number of shares usually sold in a half year exchanged hands in one hour. The banks could not supply the amount of liquid assets required, so people didn't receive money from their sales. Five days later, on 'Black Tuesday', 16.4 million shares were put up for sale, prices dropped steeply, and the hoarded properties suddenly became worthless. The collapse of the Stock Exchange was followed by economic crisis. Banks called in their outstanding loans, causing immediate closings of factories and businesses, leading to higher unemployment, and a decline in the standard of living. By January of 1930, the American money market got back on it's feet, but during this year newer bank crises unfolded: in one month, 325 banks went under. Toward the end of 1930, the crisis spread to Europe: in May of 1931, the Viennese Creditanstalt collapsed (and with it's recall of outstanding loans, took Austrian heavy industry with it). In July, a bank crisis erupted in Germany, by September in England, as well. In Germany, in 1931, more than 19,000 firms closed down. Though in France the banking system withstood the confusion, industrial production and volume of exports tapered off seriously. The agricultural countries of Central Europe were primarily shaken up by the decrease of export revenues, which was followed by a serious agricultural crisis. Romanian export revenues dropped by 73 percent, Poland's by 56 percent. In 1933 in Hungary, debts in the agricultural sphere reached 2.2 billion Pengoes. Compared to the industrial production of 1929, it fell 76 percent in 1932 and 88 percent in 1933. Agricultural unemployment levels, already causing serious concerns, swelled immensely to levels, estimated at the time to be in the hundreds of thousands. In industry the scale of unemployment was 30 percent (about 250,000 people).5 Jewish Codex

Order no. 198 of the Slovakian government, issued in September 1941, on the legal status of the Jews, went down in history as Jewish Codex. Based on the Nuremberg Laws, it was one of the most stringent and inhuman anti-Jewish laws all over Europe. It paraphrased the Jewish issue on a racial basis, religious considerations were fading into the background; categories of Jew, Half Jew, moreover 'Mixture' were specified by it. The majority of the 270 paragraphs dealt with the transfer of Jewish property (so-called Aryanizing; replacing Jews by non-Jews) and the exclusion of Jews from economic, political and public life.6 People’s and Public schools in Czechoslovakia

In the 18th century the state intervened in the evolution of schools – in 1877 Empress Maria Theresa issued the Ratio Educationis decree, which reformed all levels of education. After the passing of a law regarding six years of compulsory school attendance in 1868, people’s schools were fundamentally changed, and could now also be secular. During the First Czechoslovak Republic, the Small School Law of 1922 increased compulsory school attendance to eight years. The lower grades of people’s schools were public schools (four years) and the higher grades were council schools. A council school was a general education school for youth between the ages of 10 and 15. Council schools were created in the last quarter of the 19th century as having 4 years, and were usually state-run. Their curriculum was dominated by natural sciences with a practical orientation towards trade and business. During the First Czechoslovak Republic they became 3-year with a 1-year course. After 1945 their curriculum was merged with that of lower gymnasium. After 1948 they disappeared, because all schools were nationalized.7 Yellow star in Slovakia

On 18th September 1941 an order passed by the Slovakian Minister of the Interior required all Jews to wear a clearly visible yellow star, at least 6 cm in diameter, on the left side of their clothing. After 20th October 1941 only stars issued by the Jewish Centre were permitted. Children under the age of six, Jews married to non-Jews and their children if not of Jewish religion, were exempt, as well as those who had converted before 10th September 1941. Further exemptions were given to Jews who filled certain posts (civil servants, industrial executives, leaders of institutions and funds) and to those receiving reprieve from the state president. Exempted Jews were certified at the relevant constabulary authority. The order was valid from 22nd September 1941.8 HSLS, The Hlinka Slovak People’s Party

a political party founded in 1918 as the Slovak People’s Party, in 1925 the HSLS. Had an anti-communist, anti-socialist orientation, based itself on Catholic ideology, and demanded Slovakia’s autonomy. From 1938 assumed a prominent position in Slovakia, in 1939 introduced an authoritarian one-party regime, its ideology was a mixture of clericalism, nationalism and fascism. Its leader until 1938 was Andrej Hlinka, after him Jozef Tiso. The HSLS founded two mass organizations: the Hlinka Guards, a copy of the German Sturmabteilung, and the Hlinka Youth, a copy of the German Hitlerjugend. After the liberation of Czechoslovakia in 1945, it was banned and its highest officials put on trial.9 Hlinka-Guards

Military group under the leadership of the radical wing of the Slovakian Popular Party. The radicals claimed an independent Slovakia and a fascist political and public life. The Hlinka-Guards deported brutally, and without German help, 58,000 (according to other sources 68,000) Slovak Jews between March and October 1942.10 Hitlerjugend

The youth organization of the German Nazi Party (NSDAP). In 1936 all other German youth organizations were abolished and the Hitlerjugend was the only legal state youth organization. From 1939 all young Germans between 10 and 18 were obliged to join the Hitlerjugend, which organized after-school activities and political education. Boys over 14 were also given pre-military training and girls over 14 were trained for motherhood and domestic duties. After reaching the age of 18, young people either joined the army or went to work.11 Slovak Pospolity – National Party (SP-NS)

was a political party active in Slovakia during the years 2005-2006. On 1st March 2006, the Supreme Court of the Slovak Republic dissolved this party, because its political activities were in contravention of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic. It is the first time in history that the Supreme Court in Slovakia dissolved a political party. The party was designated by mainstream media as being extremely radical. It celebrates the wartime Slovak State. The party’s leader, Marian Kotleba, is addressed by the other members of the SP-NS with the Slovak equivalent of ‘Führer’. The main goal of the SP-NS was, in their words “to build a new Slovak Corporatist Republic on national, Christian and social principles, the secession of the Slovak Republic from North-Atlantic Alliance (NATO) and the proclamation of military neutrality, ... close cooperation with Slav states and secession of the Slovak Republic from the International Monetary Fund and other organizations that are destroying the Slovak nation and state.” The party drew attention to itself with its public manifestations in outfits reminiscent of the uniforms of the Hlinka Guard. During several manifestations they denounced the SNP as being “an anti-Slovak Bolshevik putsch and an international effort of traitors”. They criticize parliamentary democracy and in their criticism even include slogans about “Gypsy leeches and parasites”, “Hungarian chauvinists” or “the Zionist lobby”.12 Exemption and exceptions in the Slovak State (1939-1945)

in the Jewish Codex they are included under § 254 and § 255. Exemption and exceptions, § 255 – the President of the Slovak Republic may grant an exemption from the stipulations of this decree. Exemption may be complete or partial and may be subject to conditions. Exemption may be revoked at any time. In the case of exemption, administrative fees are collected according to § 255 in the following amounts:a) for the granting of an exception according to § 1, the sum of 1,000 to 500,000 Ks.

b) for the granting of an exception according to § 2, the sum of 500 to 100,000 Ks

c) for the granting of an exception according to single or multiple decrees, the sum of 10 Ks to 300,000 Ks

d) a certificate issued according to § 3 is charged at 10 Ks

§ 255 enabled the President to grant exceptions from decrees for a fee. Disputes are still led regarding how this paragraph got into the Jewish Codex and how many exceptions the President granted. According to documents there were 1111 Jews protected by exceptions, including family members. Exceptions were valid from the commencement of deportations from the territory of the Slovak State, in 1942, up until the outbreak of the Slovak National Rebellion, in the year 1944.