Gyula Foldes

Budapest

Hungary

Interviewer: Eszter Andor

Date of interview: October 2002

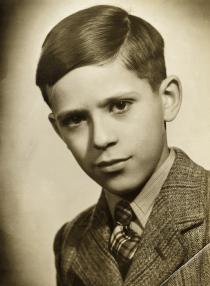

Gyula Foldes is a retired pediatrician who is still active professionally. Although he was a small child before the war, he is a very good story-teller and he has lively memories of his childhood and knows many stories and anecdotes of his family. With his second wife he lives in a nicely furnished apartment in the Ujlipot district of Budapest, a district inhabited by middle-class people and a very high number of Jews. In the room, in which our interview takes place, he shows me all the cherished books and furniture he saved from his mother and childhood.

My family background

My parents

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Married life

Glossary

My maternal grandfather was called Ignac Altman. He was born in Szent Domonkos in 1879. He started as a railroad braker but worked his way up and died as a chief ticket-inspector. I believe he finished four years of middle school 1 but had no further education. But he wanted his eldest daughter to become a doctor. And she did, too. His wife was called Roza Glatter, she was from Gyongyos. They lived in several places in Hungary, as railroad workers they were sent here and there. They were in Dunaszerdahely, then in Zsolna, but most of all in Pest at the MAV [Hungarian State Railroad] colony in Rakospalota. I have one souvenir of my grandmother, a photograph. Her face is smiley and round. As far as I know they weren’t very religious. They wore middle class clothes, observed Yom Kippur and seder, and they lit candles at Chanukkah. They didn’t observe much else. Ignac Altman died in 1926 and his wife in 1936.

Roza Glatter had a brother, Jozsef [Joska] Glatter, who was a train-driver. He became a communist. In 1919, during the Hungarian Soviet Republic 2, he had a fairly high post – what exactly I don’t know. My grandfather was a legitimist, which is why they always argued about politics. [Legitimists were the supporters of the re-establishment of the Habsburg Monarchy.] After the Hungarian Soviet Republic fell, so did Jozsef Glatter, in 1920´, I believe. He was imprisoned in Csillag prison in Szeged. My mother and aunt – my mother had a younger sister – were daughters of a railroad worker, so they got free train tickets and they went to see him in Csillag. My grandfather must have had some protection because Jozsef Glatter was sentenced to death in the meantime, but stayed in prison. My grandfather reasoned that they wouldn’t hang Jozsef as he had three children. Then the train-drivers put their heads together so as to prevent his execution. A delegation was sent to Horthy 3 to plea for him and get him reprieved. And so it was: he was sentenced to life imprisonment and then, when prisoners-of-war were exchanged in Hungary, Jozsef Glatter, who was a political prisoner, his wife and three children were sent to Moscow. On the train they met a young man called Zoltan Wienberger, who later became a minister as Zoltan Vass.

When the illegally organized parties were disbanded in Hungary Jozsef was summoned in Moscow and told to reorganize the party. They wanted to send his eldest son, Endre Glatter, who was then twenty something, to go to Pest illegally to reorganize the party. Not his father, as he had been sentenced to death. At this his wife, Nelli, said that once was enough and they left Moscow; they were able to do so as they had an apartment which a well-known GPU needed, as he wanted to get married, and he got them passports. At the beginning of 1926 or 1927 they arrived in New York from where, not long after, they went to Canada.

During the war the biggest privation they suffered was that they couldn’t get bananas. We know all this because Erzsi Glatter, their youngest, who was a hairdresser, came to Pest with her husband in 1965 or 1966, and looked us up in the telephone book as she knew my mother’s name. She could speak Hungarian, too, and told us the whole story. Another interesting point is that on the 60th anniversary of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1979 an article appeared in the Esti Hirlap [Evening News] saying that a memorial tablet had been unveiled on Ferencvaros station to commemorate an important figure in the workers movement, Jozsef Glatter. I went to see it. There’s nothing on it about when he was born or died – as they had no data about this. I started to laugh as I had already been in New York and Canada and knew that Glatter, despite his communist past, was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

Erzsi Glatter, his daughter, got to know a Jew called Feri Izsak, who came from Szatmarnemeti, and married him. He wasn’t really Orthodox but observed the traditions. They became very wealthy. The Izsaks had some land, here in Szatmarnemeti, he went to Canada in 1946 and his first priority was to buy land. He started to buy and it worked. Because, on the other side of the Canadian-American border, in Detroit, the Ford factory needed workers, and wages in Canada were much lower. So Ford started to build houses there and moved their employees in. They started to buy Feri Izsak’s land.

My mother’s sister Gizella or Giza was born in 1904 in Dunaszerdahely and died in Budapest in 1983. When she was born my grandfather was working for the Hungarian State Railroad in Dunaszerdahely and Pozsony. Auntie Giza completed for grades of middle school, but she didn’t particularly want to study. She was a very beautiful woman and wanted to get married as soon as possible. She had three husbands. The first was Ferenc Horvath, who wasn’t Jewish, but the second, Dezso Szanto, was. She married the first at the end of the 1920s, it lasted a short time, she married again in 1936. I don’t know what happened to her first two husbands. Her third husband, Karoly Altman, was her cousin. Ignac Altman had a sister called Fani, and she had a son, Karoly, on the wrong side of the blanket. That’s why he was called Altman, as we didn’t know anything of his father. Fani was supposedly a dissolute woman, I think she lived in Pest. Karoly was Auntie Giza’s first cousin, but while grandmother lived she didn’t allow them to marry because the belief was, and still is today, that cousins marrying is unhealthy. When my grandmother died they married immediately, in 1937, I think. There were only civil marriages then, and I was there. It was in Aszod, as Karoly Altman was a car mechanic and had a workshop there with a partner.

I have many memories of Karoly. He was a dark-haired, tall, good-looking man with an old Citroen car. In the 1930s this was a big thing for us, children, as we could go on trips in the car. During the year before the war, so in 1939, he worked in Pest as well. He was immediately called up, as they needed car mechanics who knew how to drive; whether he was a Jew or not wasn’t an issue; to the extent that even in 1941 he went to Ukraine as a soldier, not as a forced laborer. When he came back in 1941-42 we heard from him how the Hungarian military had behaved during the invasion. About how holding babies by the legs they had thrashed them against the walls. He wasn’t called up for labor service later either, somehow he got excused, I suppose due to his car mechanic expertise.

My father’s father, Lajos Friedman, was born in 1866 in Sirok. He was an upholstery assistant, I don’t think he ever worked independently. He lived on 20 Istvan Road in Pest. At the end of his life he lived with us in the apartment on Terez Boulevard. He died in Budapest in 1937 but insisted on being buried in the Orthodox cemetery in Gyongyos. My father’s mother was Zsofia Klein, I don’t know where she was born, but she is buried in Budapest in the Jewish cemetery on Kozma Street. I didn’t know her, she died at the beginning of the 1930s, but I knew my grandfather.

My grandmother’s father was Moric Klein, who had lots of siblings. There were two interesting personalities among them. One of them was Sandor Kellner who magyarized his name, in fact took another one and became Sir Alexander Korda. He was born in Turkeve. He was one of the outstanding personalities in the international film world; my father went to see him in London in 1939. He had two brothers – Zoltan and Vince – who got into London filmmaking. Zoltan was also a director, Vince was a set designer. Zoltan directed The Thief of Baghdad. [It was in fact directed by Ludwig Berger.] But enough of the Kordas. Moric Klein had another brother too, Korvin, who was a People Commissar during the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. They caught him and executed him.

My grandfather’s sister, Anna Friedman, was the mother of Mariska Grossman. Mrs. Nandor Grossman was born Mariska Grossman –she married her cousin. They had a house and parents in Gyongyos. In 1918 Mrs. Nandor Grossman bought this house, then it became state owned Jewish property in 1944, and in 1951 state owned Kulak 4 property. Those of the family who survived the war went to Israel after the Holocaust, in 1949. I met Auntie Mariska in 1974. She lived in Netanya, but she didn’t recognize me, only her daughter did.

I believe my grandparents certainly completed four grades of middle school, as they could read and write. My grandfather was religious, always had a cap or hat on his head, even at home. But he didn’t have a beard or payes. He wore middle class clothes: trousers, jacket, shirt, tie. The household was kosher but not Orthodox. They didn’t eat pork, lit candles on Friday night, but my grandmother didn’t have a sheitl and there were no prayers with tefillin in the morning. My grandfather attended the Neolog 5 synagogue in Dohany Street not the Orthodox one. He fasted on Yom Kippur.

My father had a younger sister called Erzsebet Friedman. She was born in 1898. She got schizophrenia, it started in her adulthood. Not getting married was her big regret as how otherwise could she have children? She was pretty, according to the photographs, but ill. An acquaintance of my father’s introduced her to a young man called Jeno Klein, he married her and they had a son. My parents adopted him because of his mother’s illness. He was born Endre [Bandi] Klein in 1930; after adoption he became Endre Foldes. Bandi always thought of my parents as his, and still speaks of them so today. His mother was in many hospitals including Lipotmezo. [Lipotmezo is a big, famous mental institution in Budapest.] Mental patients still get TB today but then it was especially prevalent. There was no proper attendance for the 16-24 bed wards and they infected each other. She got it and died of it in 1942.

We knew that Uncle Jeno was Bandi’s father as he came to see us from Rakospalota, where he lived, every week. But I think that he didn’t want Bandi with him. He probably noticed that his brother-in-law was well off. I can’t say what Uncle Jeno’s profession was. Sometime in 1943 he got married again. Then, when Rakospalota was ghettoized, they were taken away and perished. I think they were taken to Auschwitz.

My father, Tivadar Friedman, was born in 1894, in Istenmezeje, on the northern side of the Matra mountain, about 15 kilometers from Petervasar. This is such a small place that, when I needed documents for reparations, I found out that it had no public records office. But I had my birth certificate from Petervasar because at the 1939 elections one had to show how long one’s ancestors had lived in Hungary and it was issued then. I’ve never been to Istenmezeje but I’ve visited Petervasar, it is the main town in the district even today.

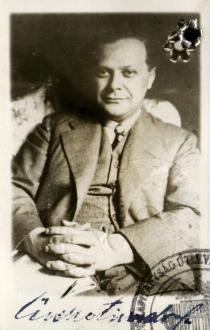

My father graduated from high school at the age of 18 and entered the English-Hungarian Bank. He magyarized his name to Foldes when he entered the bank in Fiume. This was about 1912. He wasn’t expected to, he just did. Probably because it sounded better in the bank. He worked there until the war broke out in 1914. Then, or sometime afterwards, he went to Pest to avoid being called up and from then on he was here at the English-Hungarian Bank. A few years after he married my mother – which was in 1927 – he entered a subsidiary of the bank as a chartered accountant. In the second half of the 1930s chartered accountancy meant taking an exam. He had a certificate in it. The examining board chairman was a certain Istvan Antos who, after the liberation [i.e. WWII], was a financial expert for the communist party and Minister of Finance, too, I believe. Hungarian was my father’s mother tongue, as it was for his whole family.

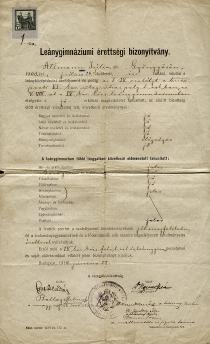

My mother was called Dr. Julia Altman. She was born in Gyongyos in 1900 and died in Budapest in 1970. She was a GP and dentist. Her father, Ignac Altman, must have had good connections in the right places because he said that he would like his daughter to be accepted into the Medical Faculty. And given that he didn’t join the communist movement during the Hungarian Soviet Republic my mother entered university in the fall of 1919. In 1924 she graduated from the Medical Faculty of Pazmany Peter University and got her dentistry qualifications later.

A fellow student of hers was Laszlo Nemeth, who was a real anti-Semite at that time and acted as one, too. [Nemeth was an outstanding 20th century Hungarian prose writer and playwright.] There were Jews in university but not many. I only know of a certain Sari Neumann in her year, she was a rabbi’s daughter and her father also wanted her to be a doctor. My mother said something to the effect that they picked on her because of her name, and she had the worst subject choices at certain exams. She worked during university, too, stuffing geese for example. Once she studied anatomy while stuffing a goose.

When she finished university she didn’t come to Pest immediately because it was usual, it may have been obligatory to go and work as a doctor in the provinces. She went to Vaja near Nyirbator. She had a suitor there, a Christian boy, who had been at university with her. But nothing came of it, it wasn’t serious. My mother came to Pest, there was a dental surgery on Jozsef street for the prisons, and she got a post there.

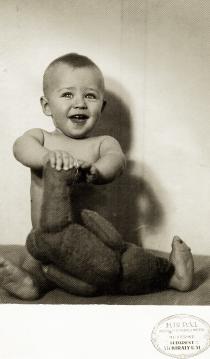

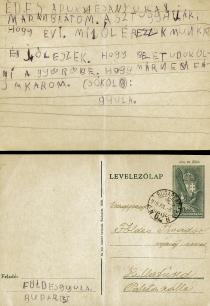

My parents got married in 1927 after my grandfather Ignac’s death. They got married in Rakospalota, I don’t know why. I have the marriage certificate and it says that the civil marriage took place in Rakospalota. They married before a rabbi, Benjamin Schwartz, in Bethlen Square in Budapest, as Istvan Road – where my grandfather and my father lived – was part of its district they went there. My mother gave birth to me in 1933.

They lived all their life in a rented apartment and apart from the apartment I live in now, I have, too. Before I was born they lived on 82 Kiraly Street. There were two rooms there and the windows looked onto Csengery Street. Then they moved to Liszt Ferenc Square because there was trouble because next to the house was an inn, the drunks misbehaved and my parents poured buckets of water on them. I was born on 4 Liszt Ferenc Square. It was a smaller apartment and my father thought, as did my paternal grandfather, that a bigger one was necessary and he looked at one in the area. He was offered one on 6 Terez Boulevard, where no one had lived for months because a prostitute had lived in it who had been strangled by her boyfriend, so people didn’t want to move in. My mother and father weren’t so bothered by this and they got it cheaply. They moved there in 1934. It had five rooms, my mother’s dental surgery was there, a waiting room and two hallways. The surgery went under the name of Mrs. Foldes Dr Julia Altman. The house was owned by a certain Mr. Sugar, a bachelor. He wasn’t a nice man. He had an ugly, little dog which we always chased with a friend of mine in order to annoy the dog and Mr. Sugar. There was always a row with the concierge, Uncle Sarkany, who said we had to be quiet and not make a row. There was a lift in the house but we preferred to run down the stairs.

My mother, who was left to bring us up, was strict and often smacked us. Here is an example of when. It must have been 1937 when Szalasi 6 and the Arrow Cross Party 7 won an election and the Arrow Cross organized a march on the Boulevard. [Editore’s note: At that time the united party of the extreme right forces was not yet called Arrow Cross but Hungarian National Socialist Party.] We supposedly loved this and on the inner corridor inside the apartment, Bandi and I cried out, ‘Perseverance, long live Szalasi!’. My mother was having a surgery at the time, she said to her patient, ‘Excuse me for a second, just stay here!’ She must have put the saliva pump in her mouth. My mother came out and we got a big smack and were told not to shout.

We had a nursemaid called Ilonka Buko. She looked after us mostly, but did some housework as well. She came to Pest because her parents had sent her to a relative of theirs as she could make a living here more easily. She got an ear infection, which wasn’t treated properly, so she entered the Pest Israelite Community Foundation’s public hospital, and went to have an operation in Szabolcs Street. She wasn’t a Jew of course but a few Christians were also patients in the Jewish hospital. She lived with us until 1943 when she had a row with Aunt Giza about something, and then she left. She was an old maid. Something must have happened to her in 1944-45 during the siege, about which she never spoke. The Russians had caused some scandal. [Editor’s note. Ilonka, as so many women were then, was probably raped by Russian soldiers.] She came back in 1946 but not as an employee. My mother confirmed that she had looked after children, and put her through some sort of college, and then she became a baby nurse in Vas Street hospital, and retired from there. She had an apartment and came nearly every day to see us.

While my grandfather was alive there was a separate part for milky and meaty products in the kitchen. There were also two maids, who weren’t Jews but had been taught how to do it [keep a kosher kitchen]. Although there was no separate sink. There was also a cook for a while, Mariska, who also lived with us on Terez Boulevard. The two Friday night candles weren’t always lit before Sabbath started as there was mother’s surgery, and if a patient came there was no way to say, ‘Sorry but we are lighting candles now’. My mother didn’t finish early on Fridays either as she was on duty at any time. She worked on Saturdays, too.

Bandi’s bar mitzvah was in 1943. He was prepared by chief rabbi Izsak Schmeltzer, the religious instruction teacher at Barcsay Street high school. Afterwards there was a big celebration at ours on Terez Boulevard. There were at least fifty people, not only Jews but Christian colleagues of my father’s, too. Somebody brought Jokai’s 8 book The Earth Really Does Spin as a present for Bandi. I also had a bar mitzvah in 1946 but only because I insisted on it. A 13-year-old child believes that externals strengthen them in their identity. I was also prepared by rabbi Schmeltzer.

My parents read Hungarian authors mostly. My mother and aunt used to say that we were brought up on Jokai’s teats, as my grandmother had read many of his books, too. I was brought up on newspapers. Wherever I am in the world I have to buy a newspaper. We had Est, Pesti Naplo and Magyarorszag delivered as my father was working in the accounts department of Est Lapok. [These are daily and evening papers.]

We were sent away in the summer for two weeks. We were six or seven years old when we first went, we were schoolboys. Until 1943 it was fine to do so. We were in Buda, on Matyas Kiraly Road, in a very comfortable villa. It was run by a nursery school teacher, there were organized activities, there were sports competitions and medals could be won. I suppose it wasn’t a cheap form of entertainment, this summer camp.

A language teacher came twice a week in our childhood for two or three years, I believe, and he taught us German. Thank God I didn’t have to learn music; my mother said that I shouldn’t be forced to. She wasn’t so interested in it either. I can only speak pidgin German and Bandi forgot it, but he learned French and English. We learned English at high school for a short time, then came Russian for eight years and Latin.

Barcsay Street high school, Madach Imre was its name, where I went to from 1943, had more than a third Jewish boys in class. Originally it had a Jewish class, and because of the anti-Jewish laws 9 only Jewish children were taken. During the German invasion, we were in the 1st grade until April 1944, then the Jews dropped out. I still went to school with a yellow star.

In 1944 my father’s cousin, Jozsef Rubinstein, was deported from Heves, along with his wife, two daughters and their children. Only one returned, one of the daughters, who is now in a mental institute in Israel. Jozsef Rubinstein was wounded in World War I, he lost an eye and received a gold service medal. As a result he had some protection, which meant that he could keep a beer warehouse in Heves. When, after the war, Aunt Boske, his daughter, returned, she went on with it. My father, who was a clear thinker, sent a Christian woman to Heves in April 1944 to tell Rubinstein to send his two grandchildren to Pest, as he believed that they had a better chance of survival there. But he said that it wasn’t true, as the paper of the Jewish community had written that there would be no trouble there. Although the leadership of the Pest Israelite Community, with Samu Stern at its head, knew quite well what would happen. Boske survived as her six-year-old son, Lali Hertz, was led by his grandmother and she held their luggage. Her younger sister, Zila, went with her child in her arms and so Mengele sent them to the left, that is, among those who were gassed immediately. [Editor’s note: It’s only a presumption that Mengele himself selected people.]

The house on Terez Boulevard wasn’t a yellow star house 10 so we had to move out of the apartment. The house in Jokai Street where we moved to belonged to the Fonciere Insurance Company, their offices were on the second floor. Even when it became a yellow star house in June 1944. But at the end of October 1944 it was a refuge for Swedish embassy employees, with diplomatic immunity, thanks to Raoul Wallenberg 11. The Jokai Street apartment was smaller, with three rooms. It was a forced exchange. My father, mother, brother, aunt and uncle Karoly lived there, as well as me. When Wallenberg was operating then there were too many, at least 20-25 people lived there. Then we, the family, squeezed into a room.

Christian inhabitants were still in the house, who didn’t leave – and significantly the concierge, too. On the night of 7th to 8th January 1945, at the ‘charitable request’ of the concierge, an armed Arrow Cross company appeared. Either he had told them that there were Jews there illegally, or he thought he could get something out of it, whatever. I don’t know. The thing is that night a few Arrow Cross turned up. I was eleven. They took everybody who could be moved – anyone who couldn’t was shot – to the Arrow Cross building on 14 Varoshaz Street. Wallenberg got to know of it and appeared at the Arrow Cross building, so the next day they took us to the ghetto, to 54 Akacfa Street. My father and uncle were taken to the banks of the Danube 12 on the following day and shot into the river. The bodies never appeared. The liberation happened on 18th January 1945.

When the ghetto was liberated on the morning of 18th January we went back to Jokai Street. Much had been taken, but strangely enough the furniture was there, it hadn’t been burnt. The Russians were very close then. Only personal effects had disappeared, the radio and such had to be given in in May, but things like clothes had gone. Later, I think that summer, my mother looked up to the second floor, while out on the corridor, and saw her clothes on one of the ‘dear’ fellow residents. That kind of thing happened too, but there was only a small row about this, shouting, and then I think she gave them back. The silver, porcelain and such partly remained. My mother was a dentist, she had a fairly big clientele and acquaintanceship, and she had given things to others; she got them back later, not everything, but most things.

After the war, when it became clear that no one was alive, my mother and her younger sister, Aunt Giza, decided not to stay in Hungary. They had connections with the Glatters in Canada, who had invited them, but not really seriously. Then they tried the Zionists. Bandi was part of a Zionist company, two of the pillars of which were Pista Hermann and Agi Heller. [Hermann was a psychologist and Heller a Marxist philosopher.] In 1946 they got together, ten or so children to go to Palestine. At that time there was still some gold at home, which my mother gave to Bandi, who was then 16. Then Aunt Giza also went, not with the Zionists, but with Russians, as a mediator, on a truck to Austria into the American zone, not the Soviet one. The intention was that Bandi and Giza would meet.

Bandi got to Brussels with the Zionists. But the sheliach was very strange, or rather he wasn’t a man of high character, as he said that the children had so much gold on them that they should give it to him; it would be safer with him. [Sheliach is a Zionist representative.] They handed it over and then in Brussels the sheliach and his girlfriend disappeared. The 12-13 children were left with no money, or anything. The police caught them and put them in prison. In the meantime Aunt Giza had gone to Paris via Germany, as my father had three cousins who lived there and she knew that. She also knew they were called Friedman, but not where they lived or what they did. In the refugee camp in Paris – there’s luck in the world after all – she asked whether anyone knew Imre Friedman, and someone said yes and took her to him.

The three cousins had gone to France in 1929. They hid during the war, Joska was hidden by a Christian woman, whom he then married. She was a very nice woman. She’s still alive, but she must be very old now. I remember Uncle Miklos, and Uncle Imre was a communist. After the war Joska, the youngest, drove a taxi in Paris; Uncle Miklos retired, I think. Uncle Imre was originally a fancy-leather goods maker, then became a partisan, and as he took a very active part in things, he was given a medal, which he won for his part in the battle for the liberation of Paris. He got a travel document for himself, went to Brussels for Bandi, and brought him to Paris. All this happened in the fall of 1946. Bandi and Aunt Giza no longer thought of going to Palestine, or even Canada, but stayed in Paris. My aunt became a cook in a kind of Jewish refuge.

Bandi finished high school there. He applied for the Department of Chemistry and Physics at the Sorbonne but then something happened. He met a girl who was Jewish and a communist, and she took him to an anti-Tito 13 protest in 1950. And whom did the police catch? Bandi, of course, and two other guys, and as they were refugees they took them to Sante prison for trial, and they informed Aunt Giza who, huffing and puffing, went for him. Bandi was sentenced to two days imprisonment and thrown out of France.

In the meantime Aunt Giza had a row with the Jews, as they told her that such a godless man who does such things like protest must be abandoned to his fate. Auntie needed no more, ‘You call yourselves Jews, Orthodox religious ones at that’, she shouted, left everything and came back to Hungary. So in August 1950 they all turned up in Pest. Aunt Giza was a bookkeeper, she found a position at the Ganz Electric Factory.

Bandi graduated from university here. Bandi’s wife, Ibolya [Ibi] Krausz, was a mathematics-physics teacher; they met at university. They married in 1955. Then in 1957 they went to Montreal. Bandi was well set up, in that he spoke perfect French and English so that he had work in a week. It took a little longer for Ibi. She was an assistant in the Jewish hospital in Montreal. When De Gaulle made Quebec French, in 1966, I believe, then capitalists started to flee west towards the English speaking territories. Before this Ibi had completed her first computer course, which was at the English-language university in Montreal. When she finished it she got a high post in Northern Electric, a leading telecommunications company. When capitalists started to flee west their company moved its headquarters to Toronto. They have lived there since. Bandi got a job there, too. In the end he became a research director for a big pharmaceutical company. So it worked out for him. A boy and girl were born to them, the boy was circumcised but I don’t agree with it, primarily because it is such a final act, which perhaps should involve the boy concerned to agree with it. And naturally that can’t be so with a baby. The other reason is that a relation of a friend of mine was shot in December 1944, in Pest, because he was recognized by an acquaintance and the Arrow Cross undressed him and shot him.

Ibi’s papa and mama were fairly religious people. They weren’t Orthodox but Uncle Vili, her father, observed the traditions. They were from Pest originally, went to the synagogue, fasted. In the 1960s they followed their daughter abroad. And they observed the holidays while Uncle Vili was alive. They must have observed certain basic kosher laws as well. Uncle Vili’s wife, Emmi, was originally a greengrocer. She really hated our family. That’s the reason why I didn’t stay over there in 1970 when I went to visit. Emmi died in 1977.

To return to me: from May until mid-June 1945 we underwent a very condensed school year. In the 5th year we were given the choice of learning Russian or Greek. As believers in left-wing ideas we thought that Latin was enough of classical languages, it was anyway taught in the upper years of high school, so of course we chose Russian. The class was split: the majority chose Russian as they thought they didn’t need Greek as well as Latin. But there were a proportionally high number of Jews in the class, as Jews chose this language rather, and came over from other classes because of the Russian. In fact there was nothing anti-Semitic, at least not in those days. Before there had been; Mr Monoki, the gym teacher hit the Jewish class mainly, by making the children stand up and bashing their heads together. Apart from rabbi Schmeltzer I can’t remember any other Jewish teachers. I didn’t have a favorite teacher. I got into the Medical Faculty because of my mother.

Two relationships survived from elementary school. One, Peter Held, now lives in New York and we have been friends since September 1939. We started school then and indeed lived in the same building. The other went by the name of Pali Hollander, who also lives in America, a university lecturer, who is now retired. On 6th October 1948 I went to a brothel for the first time with Held, during the fall holidays, to Madame Clarisse on 84 Kiraly Street. We went there several times until the brothels were closed and Peter left in 1949. At the end of the 1940s it was completely normal for young boys to go to brothels. My father’s cousin, Uncle Arnold, who was a rich man, gave me some money for it, 100 forint. Then we would visit each other to play cards, with Szinetar, Peter Polgar, Sommer, Gyuri Szabados – my classmates. Miklos Szinetar’s father, Erno, was a psychiatrist and the director of the Janos Hospital. Peter Polgar became a tax expert.

I argued with the Zionists, Agi Heller’s group, fairly quickly. I, for example, am still happy to wear a tie; I went to see them wearing one, and they said I couldn’t go there in a tie. I said, ‘Then I bid you adieu.’ This was in 1947 or 48.

I entered university in 1951. They didn’t want to take me, despite the fact that my mother was a party member; at the Csengery Street surgery she was even party secretary. At that time there was a ‘wise’ party directive that medical dynasties weren’t encouraged. But one of my mother’s cousins, Imre Zador, held a high post in the medical union, he was on friendly terms with the dean of the Medical Faculty, and so I was accepted into university without any problems.

My mother was elected party secretary in a secret ballot. She was a single mother, so she had the heavy burden to have to support us. She didn’t get a higher salary, but at least they left her alone. The fact is that they weren’t very pleased that her sister and her child didn’t live in Hungary, but she wasn’t dismissed.

There was an anti-Semitic current at university. The university party leadership was a People’s College 14 crowd. But there were many Jewish lecturers at university. We believed the Rajk trial 15 and then again we didn’t. We guessed that something was wrong, but truth is it didn’t affect us. We didn’t pay attention to the scale of deceit going on.

My mother continued her private clinic until 1954, then she disbanded it because she went into two eight-hour shift jobs, first in the Csengery Street surgery, and then to Kispest. Under the Rakosi regime 16 the surgery wasn’t threatened, it wasn’t taken over by the state. Anyone who had a registered surgery was left completely alone. Of course my mother was a member of the Health Workers Union, and of the party since 1945. Rakosi’s signature was in her membership book. She thought that the communist party was the place for left-wingers. Why not the social democrat party, I don’t know. I believe it was because her colleagues and circle of friends swayed towards communism. And there was some satisfaction in it, in that it was possible to give back something of what we had been through, but not revenge exactly. And the communist party was more suited for this, or at least it seemed so.

We had no problems, neither under Rakosi nor Kadar 17, especially not under Kadar. Only in that my mother was looked at askance because her other child didn’t live in Hungary. But when Bandi came back in 1950, after being kicked out of France, my mother wrote a letter to Rakosi to get Bandi a Rakosi scholarship. He got it for a year and was accepted into university easily. So I can’t say that we had any real problems.

In regard to 1956 18 I saw myself, written in the Medical Faculty ground floor toilet, at 26 Ulloi Road, ‘Itsik we won’t take you to Auschwitz’. [Itsik is a common Yiddish name, which was used in anti-Semitic slogans and sayings in Hungary.] On 1st September 1956 I started to practice in Szabolcs Street hospital, the first three months were in surgery. In the days following 23rd October 19 I was in the emergency ward and when Kossuth Square took place on the 25th, an event which even today hasn’t been fully explained, many wounded were brought in. [Editor’s note: Shots were fired into the crowd from the roof of the Agricultural Ministry, which is opposite the Parliament building on Kossuth Square, most probably by the secret police.] Soon one of them died in my arms, it was my first such experience. People were brought in and died, so that I just left it all, and ran home down Podmaniczky Street. I stayed at home for a good while, my mother told me to stay put and she stayed at home, too.

After 1956 one didn’t need to leave the party, one just didn’t join again. My mother didn’t join the party any more. I joined in 1974 when the party was being improved a bit and remained a member until 1989. But I made clear in advance – this was a year after the Yom Kippur War 20 in Israel – that I didn’t think the Jews had been the aggressors. My colleagues said – they were Jews too who tried to convince me to join – that they thought the same, it didn’t count, one could join the party. One of them had said earlier that joining wasn’t like signing up for a package tour. Yet it was proscribed that one had to apply in advance. I didn’t undertake any party function, I was just a mere party member. Every year, after the summer break, there was the first membership meeting in September. I always sat in the first row next to the director for the simple reason that I didn’t want to nod off. The director was a Jew, too, he always asked me when the Jewish holiday would be because then he would go to the cemetery, to his parents’ grave.

I entered MAV hospital in 1979 to be more independent, as a position opened up there because the head physician had retired. So I became head of the children’s ward without any connections or even applying for it. Yet the hospital was traditionally an anti-Semitic one, which had formerly been called Miklos Horthy Hospital. There was a doctor called Sandor Csia, one of whose close relations, of the same name, had been hung with Szalasi. This Csia was no different. I experienced so much anti-Semitism that when a new surgeon arrived and a theater sister asked me, ‘Is that a trimmed prick, too?’ I said, ‘No, but I am, so could you please leave the room’. I didn’t acknowledge her from then on; she tried greeting me twice but I just looked through her.

Israel, as a place to emigrate to, never came up. My mother had a colleague whose daughter, or niece, went to Israel with the Zionists. She was shot close to the West Bank border. Then Bandi’s similar story, the Paris one, didn’t endear it to us. But in 1974 I went to Israel illegally. I went because I had friends in Zurich who organized the visa for me there; it consisted of a huge sheet of paper so that there would be no trace of it in my passport. Nobody ever found out. To get a passport for Switzerland wasn’t so difficult. We could get one every three years, as my girlfriend at the time, Eva, and myself both still had family in Hungary. I was a pediatrician in Szabolcs hospital by then, and Eva was a chief skin specialist at Heim Pal hospital. One can imagine what references I got from Szabolcs hospital as 80% of the staff was Jewish. [Szabolcs hospital was originally Pest Jewish Community hospital, nationalized in 1950.] I was later a head doctor in MAV Hospital, where they didn’t dream of saying anything bad about me. I had only been refused a passport to go to Israel before 1967, so that by 1974 I didn’t even attempt to say I expressly wanted to go there.

My first wife was Anna Vidor. Her grandfather, Dr. Odon Kalman, was the chief rabbi of Kobanya. [This is a working class district of Budapest.] Her father, Dr. Pal Vidor, was a rabbi at the Zsigmond Square synagogue. Her father had been killed in Mauthausen, her mother was a Hungarian-French teacher at Trefort. I met Annuska, as I called my wife, when we were 18, in 1951. After seven years of courtship we married in 1957. We met at the Sport swimming pool through friends. But we couldn’t have got married while at university, neither her family nor mine were rich. Annuska was also a teacher at Kolcsey high school, she taught Hungarian. She is now retired. After three years of marriage we had a bitter divorce as she fell in love with a colleague, who divorced his wife and married her. I was very hurt.

Then I fell in love again, with Anna Dobos, but no marriage came of it. She was a pediatrician, like I was at Szabolcs Street hospital. Her grandfather had been a rabbi in Dunaszerdahely. A friend of mine said that this idiot, meaning me, always wants to marry a rabbi’s daughter. I’m still in contact with her, it really was a great love. But we didn’t get married, not because of me, but because in 1964 she went to New York on a scholarship, following another boyfriend of hers, and thought that her career was better off if she saw something of the world, rather than getting married to me. I believe she was right because we wouldn’t have grown old together, that’s for sure. She had no children later either.

My next girlfriend wasn’t my wife either. Eva Torok was in my year, I would say that she is the best skin specialist in Pest. It was my stupidity that allowed the relationship to go on for 14 years, because half of it would have been more than enough. We got together in 1969, two years after her husband, who was my boss in Szabolcs Street, died. Eva became a widow with two children.

I married Eva Redei in 1984. This was also a great love. Eva was born in 1947, she has been a bookseller since she was 18. She was already working on Pozsony Road in 1988-89 where she has a shop today, and they sold the Lang Publishers’ books. The owner of the publishing company always went into the shop, to Eva, whom he only knew by sight, to ask how his books were selling. And one day Eva said to him, ‘Listen here, buy me, along with the bookshop, and then everything will be easier’. The next day he came back and said, ‘You had a very good idea, I will think about it and then do it.’ That way Teka Company was born; it included the Lang Publishers, the Book Distributor Company as a state company, Eva, and two other employees, who got less money. It opened on 1st September 1989, and this was the first private business which included a state company as well. Since then they bought a part of the Book Distributor Company, and today Eva is a major shareholder in the store.

I got to know Eva because she worked in the bookshop, and in those days I got quite a lot of books in lieu of tips, and I had two of the same, so I went to Eva to exchange them. Then when she got together with Gabor Deak, her first husband, and her tummy started to expand, she said – as she knew I was the pediatrician for everybody here – that I should be theirs, too. Her son, David, was born in 1976, and I went to their place so long until Eva divorced Gabor. It was a fairly disastrous marriage, and I can say I was sacrificed to my profession as David grew up with me in the end, with both of us. He was eight when we got married.

I’m at daggers drawn with religious belief. I’m a conscious materialist, an atheist. I don’t deny that it began as an emotional thing. We were all taken away on 8th January 1945. What happened to my father exactly, I will never know. I observe his Jahrzeit, albeit not on the day of his death because I don’t know it, I light a candle. The religious holidays are a neurotic point for me. I refuse to observe them. For example at Chanukkah or seder the family is together. I had this last in December 1944. And I believe that at the age of ten I didn’t deserve such a fate from the Almighty. Then, when I became a doctor, for eleven or twelve years out my 42 years of practice I did autopsies. Anyone who does an autopsy knows what is inside people’s bodies. Belief in God is far removed from such things.

Someone, who escaped from the Arrow Cross building on Varoshaz Street, told me that my father had fasted. It’s not as if he was given a lot to eat, but he ate nothing. That’s quite enough for me not to want to keep up with the organized part of the Jewry, including the entire leadership, past and present of the Pest Israelite Community. I haven’t been to the synagogue since 1949 when religious instruction was taken off the curriculum. Perhaps as a demonstration I will go on Yom Kippur, Kol Nidre. But I’m just as much a Jew as anyone who observes the religion. A Jewish upbringing means that you should know what happened to your grandparents, what happened to your father.

I only insist on one thing, being buried in a Jewish cemetery. I also say where, in my grandfather’s grave in Gyongyos. Burying my mother wasn’t easy. I went to the Chevra and wanted a cremation as that was her wish. If five million Jews were burned she didn’t need a special burial, at which the Chevra said that such burials take place on Monday. But we don’t bury Jews on Monday. ‘What’s this, does it mean she’s not a Jew?’, I said with great fury and slammed the door on them.

We were glad of the political changes but its downside is that traditional anti-Semitism in Hungary has arisen anew. But we belong to that 13,500 people who – unlike many – wrote in the last census that we were Jews. My circle is mixed anyway. Let’s say most are Jewish. Every three of four months we gather, twelve of us.